By Eric Niderost

U.S. General Winfield Scott’s army climbed through the mountains of central Mexico, an arduous trek that included blistering hot days and bitterly cold, rain-drenched nights. On August 10, 1847, Maj. Gen. David Twiggs’ First Division, the leading element of Scott’s army, reached to the crest of a ridge that formed the base of a snow-capped volcano known to the Mexicans as Popocatepetl. From that vantage point, some 3,000 feet below them, the Americans beheld the Valley of Mexico spread out like a lush green carpet.

The view must have been breathtaking in more ways than one. The spectacle was indeed wondrous, but they were also 10,000 feet above sea level, and the air was thin at that altitude. A soldier carrying a 91/2-pound musket, together with a canteen, haversack filled with personal items, ammunition, bayonet, and blanket, which taken together weighed 30 or more pounds, was bound to experience some labored breathing.

Nevertheless, all thoughts of fatigue were forgotten when they beheld the spectacle before them. The Valley of Mexico was the heart of the nation, where a “circle of stupendous, rugged and dark mountains” circled its rim like a snow-mantled crown. Three great lakes, Texcoco, Chalco, and Xochimilco, shimmered in the distance like some otherworldly mirage.

The lakes were complemented by a lush green plain speckled with Indian villages and white haciendas. But sooner or later all eyes were drawn to Mexico City, some 25 miles away from the American vantage point. The city’s magnificent buildings were punctuated by green trees, and numerous church steeples spiked the sky. Scott, commander-in-chief of the American expeditionary force, was exultant. “That splendid city will soon be ours!” he said.

The Mexican-American War was the inevitable result of tensions that had been building for a decade or more. The United States had a dynamic, growing, and land-hungry population, and Mexico possessed a western empire stretching to the Pacific that was rich but sparsely settled. Political considerations, seasoned with cultural, language, and even religious differences, made compromise impossible.

James K. Polk was elected president on a platform of Manifest Destiny. That doctrine held that it was America’s God-given fate to advance to the shores of the Pacific. Polk tried to buy California and the Western territories, but when he was predictably rebuffed by the Mexican government he engineered an incident that led to war. A skirmish between Mexican and American troops on disputed territory allowed Polk to boldly proclaim, “American blood has been shed on American soil.”

A few were skeptical about Polk’s claims, such as U.S. Representative Abraham Lincoln, but the vast majority of Americans were wildly enthusiastic about the war. Nevertheless, after some months of fighting it was clear that the Mexican capital itself would have to be taken before the Mexicans would ever capitulate. Scott, America’s premier soldier, was given the task of landing at Vera Cruz on the coast and then fighting his way some 279 miles through the mountains to Mexico City.

Scott’s assignment was unenviable, and at the start of the campaign most Europeans felt Mexico would emerge the victor. The U.S. Army’s performance in the War of 1812 was mixed, and it had more experience fighting Indians than conventional armies on foreign soil. The Mexicans would be fighting on their home ground, and they had a powerful ally in their country’s formidable geography. The rough roads that wound through precipitous mountain ranges were perfect for defense. Making matters worse, the coastal regions were plagued by yellow fever.

In spite of all these difficulties, Scott persevered. The Americans landed near Vera Cruz, taking the city on March 29, 1847, after a short siege and a particularly heavy and effective bombardment. Scott and his 8,500-strong army departed for Mexico City via the National Road. This was the route that Cortez had taken in 1519, more than 300 years earlier, to conquer the Aztecs.

General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, the victor of the Alamo, awaited Scott at Cerro Gordo. After a fall from grace, Santa Anna was once more Mexico’s supreme leader but knew his power depended on his ability to defeat the Americans. Though much ridiculed for his greed, pomposity, and overweening vanity, Santa Anna was a good general and under pressure could rise to the occasion. His position at Cerro Gordo, which effectively blocked a mountain pass that led to the capital, was a good one.

One of Scott’s engineers, Captain Robert E. Lee, found a way around the Mexican positions. In a sharp fight on April 18 the Mexicans were flanked and forced to retreat. Approximately 3,000 Mexican soldiers were captured, and Santa Anna himself fled so quickly he left his wooden leg behind. It was an American triumph against formidable odds.

Only a few days later, however, Scott faced a crisis at Jalapa. His army, already small, was going to be reduced by the departure of 3,000 volunteers. Their one-year enlistments were up, and Scott felt in good conscience he could not restrain them. He also was faced with a logistical nightmare, because his supply line was a long one that stretched back to Vera Cruz. The Americans had established garrisons along the route to keep that vital corridor open.

Scott decided to order all those garrisons to abandon their stations and join him. At one stroke his bolstered the numbers of his field army but also cut himself off from the coast. It was a bold and audacious move that left European observers dumbfounded. The Duke of Wellington, who had defeated Napoleon at Waterloo, declared, “Scott is lost! He has been carried away by his successes! He can’t take the city [Mexico City] and he can’t fall back on his base.”

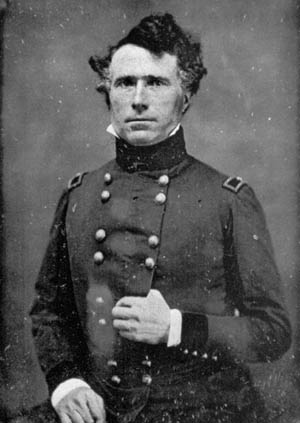

Scott stayed in Puebla for three months from May to August, and during this period reinforcements trickled in. Among these were Brig. Gen. Franklin Pierce, a politician turned soldier, and 2,400 volunteers. By August, Scott was ready to march again, especially since peace negotiations with Santa Anna seemed to have fallen through.

In the meantime, Santa Anna was gathering a new army and preparing the defenses of the Mexican capital. The defeat at Cerro Gordo, and an earlier reverse on February 23 at Buena Vista against Maj. Gen. Zachary Taylor, had tarnished his reputation. But Santa Anna’s record was quickly forgotten, or at least forgiven, when Scott approached Mexico City. For all his faults, he had a genuine charisma that appealed to Mexicans in times of crisis.

Mexico City buzzed with activity that spurred a rising patriotic zeal. Church bells sounded the alarm, a deep-toned cacophony that echoed across the valley in a clarion call to duty. After much reflection, Santa Anna decided to block the National Road at El Penon, a hill that was about 10 miles from the city proper. This well-fortified post would stop the invaders in their tracks.

The Grand Plaza of Mexico City, today generally called the Zocalo, was the scene of an impressive spectacle as the Mexican army marched out to defend the city. The brigades that marched out past cheering crowds were a cross-section of the city’s population. The Independencia Brigade, for example, was composed of tailors, bricklayers, and carpenters who carried older muskets because that was the best they could afford.

Later that day, Santa Anna appeared on the Grand Plaza surrounded by a glittering staff and an escort wearing resplendent uniforms. Thousands of voices cried, “Viva Santa Anna!” as he rode by, acknowledging their cheers. Further cries of “Viva la Republica!” filled the air as drums beat a throbbing martial tattoo and ladies waved from balconies.

But would the Americans really come up the National Road as anticipated? Scott had intelligence that El Penon was heavily fortified, but he wanted to confirm the findings. Once again, Lee and a party of other engineers were sent out to reconnoiter the position. Lee reported back that the El Penon position was indeed strong and defended by at least 7,000 troops.

But the Americans were aware that there was another road that snaked south through a narrow isthmus between Lake Chalco and Lake Xochmilco, which then turned west to San Augustin. At that location, it joined the Acapulco Road, which led north to Mexico City. When he learned this from the engineers, Scott needed no persuasion. The Acapulco Road would be Scott’s new axis for his advance. The American army would follow this newly discovered route, thereby executing a classic turning maneuver on an unsuspecting Santa Anna.

It took Santa Anna two or three days to become fully convinced that Scott had stolen a march on him. Adaptable as always, he shifted his forces to new defensive positions to counter Scott’s moves. The Mexican leader spread his 25,000 men in a line about five miles wide, with natural obstacles providing further defense.

The shortest way to Mexico City was via the Acapulco Road, through the San Antonio hacienda. The Americans would soon occupy San Augustin, about five miles farther south. Santa Anna lost no time in building strong fortifications at San Antonio, which once again blocked the path to the capital. The position itself was strong and could not be immediately outflanked. To the west was the Pedregal, a large lava bed of razor-sharp rocks, and to the east the ground was impenetrable marshland.

Scott’s situation was becoming desperate. The American horses needed fodder, and rations were short and growing musty. His army had only about 10,000 effectives, confronting a Mexican army of 20,000 men fighting on their own soil. But perhaps there was a solution. If the Americans could find a way near or through the Pedregal’s southern edge, they could circle around the lava and get behind the San Antonio fortifications.

Lee once more came to the fore. He did an extensive reconnaissance, and on August 18 Lee reported that he had found a mule track across the southwestern tip of the 15-mile-wide lava bed, which might be widened or otherwise improved, at least enough so it would be passable for infantry and artillery. Hearing this, Scott quickly formulated new plans. Lee would take some 500 men to act as sappers and improve the approach as best they could.

In the meantime, Twiggs’ division would take the lead, at the same time protecting the road builders. If Twiggs got into trouble, which Scott felt was unlikely, Maj. Gen. Pillow’s division would come up, and Pillow would take command of the entire force. Twiggs was not happy over this arrangement, but Scott felt the point was not worth debating since the commander in chief would soon join them.

Mexican politics were sordid in this era, a Machiavellian nightmare as scheming generals jockeyed for power and their own selfish interests while the fate of the nation hung in the balance. General Gabriel Valencia, while technically subordinate to Santa Anna, was an ambition-driven man who hoped to replace his one-legged chief. Against orders, he moved his Army of the North five miles beyond Santa Anna’s original defense lines to a position between the Indian villages of Padierna and Contreras.

Santa Anna immediately ordered Valencia to move back to San Angel, his original position. Valencia gave Santa Anna lip service, but did not budge a foot. Finally, Santa Anna gave up in disgust. He would “leave Valencia to act on his own responsibility.” Of course, what Valencia really wanted was a chance to defeat the Americans singlehandedly and emerge as Mexico’s new hero.

The road builders moved out on the morning of August 19. The American soldiers were tough and inured to hardship, but hacking a path through this lunar-like landscape of jumbled volcanic boulders proved difficult, backbreaking, and dirty. They made good progress until they reached a point overlooking Padierna in front, San Geronimo to the right, and Contreras to the left.

At this point Twiggs’ men came under heavy artillery fire from no fewer than 22 Mexican guns. Though the Americans did not know it, this was an element of Valencia’s command, now firmly ensconced in the Contreras area. Twiggs immediately ordered two American batteries up to reply to this cannonade. It was an order more easily said than done.

George Ballentine, an Englishman in American service, was a soldier in one of the units called up, namely Captain John B. Magruder’s 1st U.S. Artillery. He later wrote that the lava bed was so rough and treacherous that often they were brought to an abrupt if temporary halt. “We had to lift the [gun] carriages as if over a wall,” he wrote, “the men lifting at the wheels and the horses whipped to their utmost exertions at the same time.”

At first Valencia could not believe the Americans had crossed the Pedregal. “No, no, you’re dreaming, hombre!” he said to the messenger who brought him the news. But once he accepted the idea, his joy knew no bounds. He had defeated the Yanquis and gained fresh laurels for himself.

But as the artillery duel increased in fury, Valencia seemed to be obsessed with its progress to the exclusion of all other fronts. Pillow ordered Colonel Bennet Riley to take his brigade and occupy San Geronimo, the idea being to get behind Valencia and cut him off from his lifeline, the San Angel Road. Other units joined Riley until there were about 3,500 Americans in and around San Geronimo.

As the American infantry worked its way through the Pedregal to join Pillow, they found the going very tough. Lee’s sappers had done their best, but apparently there were stretches that were little improved. Soldiers were forced to have a “compelling rapid gait in order to spring from point to point of rock, on which two feet could not rest and which cut through our shoes,” wrote a soldier in Riley’s brigade.

The Americans at San Geronimo were in grave danger. A large body of Mexican troops could be seen at San Angel, just about a half-mile up the road. There were some 7,000 of them, commanded by Santa Anna himself. If Santa Anna showed any initiative or drive, he could crush the American troops, his hammer striking them against Valencia’s anvil.

Seeing the problem, Brig. Gen. Persifor Smith joined the American forces at San Geronimo, arriving just about an hour before sunset. Though he kept a wary defensive eye on Santa Anna, Smith planned an early morning attack on Valencia. But Smith felt it was imperative that Scott know about it. Not only was night falling, but thick gathering clouds announced the coming of a thunderstorm.

This meant a nocturnal crossing of the Pedregal under the worst of conditions, but Lee was undeterred. Lee left about 8 pm, groping forward in the pitch blackness in a pouring rain. The captain was guided by his uncanny sense of direction, a small lantern, and lightning bolts as they flashed through the sky. Carefully, almost gingerly, Lee and his small party threaded their way past jagged outcroppings and treacherous crevasses that threatened to swallow them. Lee, drenched and sore, found Scott after 11 pm.

Ironically, this torrential downpour worked in the Americans’ favor, since Mexican pickets had left their positions because of the bad weather. In the meantime, Santa Anna did virtually nothing to help or reinforce Valencia. Santa Anna’s lack of movement was due either to lethargy or a desire to see his rival crushed.

When the Americans attacked at dawn, they caught Valencia’s men completely by surprise. Wet and cold, they were disheartened by Santa Anna’s failure to reinforce them. When the Americans attacked, the majority of Valencia’s men broke and ran. Valencia had been in an ebullient mood, mistaking the earlier artillery duel as a great Mexican triumph. It was said that Valencia spent the previous night celebrating his “victory” by getting roaring drunk.

The so-called Battle of Contreras on August 20 lasted only 17 minutes. Santa Anna now hoped that the Americans would be stopped at Churubusco with its fortified convent, earthworks, and seven cannons. The Churubusco River fronted the Mexican position, and a bridgehead fort guarded the approaches on the south side of the stream. The fortified Convent of San Mateo, founded by the Franciscans, was to the southwest, about 500 yards away from the Churubusco Bridge.

Santa Anna gave strict orders that the bridgehead and convent were to be held at all costs. One Mexican unit in particular was determined to fulfill his instructions to the letter. The San Patricio Battalion was largely composed of Irish and German immigrants, many of whom were veterans and deserters from the U.S. Army. It was said they received their name and outwardly Irish flavor because of their commander and founder, John Riley.

The men of the San Patricio Battalion came from different countries, but on the whole it was their Catholic faith that united them. At the time, Catholics often faced discrimination in the United States, where the bulk of the population was Protestant. Few of them were American citizens, or even American born, so they had little love for a country that seemed to despise their religion.

By the same token, many were deserters from the U.S. Army, and they knew that if captured they faced the draconian punishments that were common to the armies of that period. They might be brutally flogged, branded, or even hanged for their desertion. They knew their fate if Mexico were defeated, which provided a powerful motivation to resist at all costs.

The usually cautious Scott dispensed with reconnaissance and ordered a full-scale attack on both the bridgehead and the convent. Learning that there were two other bridges across the Churubusco River, Scott sent Brig. Gen. James Shields and Brig. Gen. Franklin Pierce north to cross one of them and go on to the town of Portales. This would put Shields and Pierce behind the Mexican defenders at Churubusco.

Scott underestimated the strength of the Churubusco positions. The better course would have been to send the bulk of his army with Shields and Pierce, neatly outflanking and getting behind Churubusco. All of the formidable fortifications would have been neutralized in one stroke.

Most accounts say the Churubusco defenders were supported by powerful artillery. In addition to the men of the San Patricio Battalion, other Mexican units that participated in the fighting were the Independencia Battalion and Los Bravos Battalion, with some elements of the Tlapa and Lagos Battalions in support. The convent was commanded by Brig. Gen. Pedro Anaya, and the strategic bridgehead fort on the south bank was under the command of General Francisco Perez.

Scott committed virtually all his forces to the Churubusco advance. Maj. Gen. William Worth and Pillow would attack the Churubusco Bridge and the bridgehead fort, while Twiggs would advance on the convent. Shields and Pierce were already committed to the northern flank march. Pierce, handsome and dashing, would become a somewhat ineffectual U.S. president a few years later.

The Mexicans fought well in the initial stages, but as time went on they were hampered by a lack of ammunition. When an ammunition wagon belatedly arrived, the cartridges were of the wrong type for the majority of the weapons, rendering them useless. Nevertheless, the Mexican soldiers at the bridgehead fought courageously, repulsing several American assaults.

The Americans took heavy casualties but pressed on, courage meeting equal courage. Elements of Colonel Newman Clark’s brigade, which included the 5th and 8th U.S. Infantry, took the bridgehead fort with the bayonet, ably supported by Brig. Gen. Cadwallader’s 11th U.S. Infantry and 14th U.S. Infantry.

The Americans had endured a punishing fire as they approached the bridgehead, and once inside the fort the hand-to-hand fighting was intense. When his soldiers won, Worth felt his heart “filled with gratitude.”

But the Mexicans were not finished. They withdrew into the walls of the convent, intent on a last stand. The San Patricio men were the heart and soul of the defense at this stage, refusing to even consider the possibility of surrender. According to some accounts, the San Patricio Battalion singled out advancing American officers for special attention, killing all they could. It was their revenge for the abuse many had endured as common soldiers in the ranks.

After a battle that lasted 21/2 hours, Mexican ammunition was running out, and several of their cannons were out of action. But when a Mexican officer tried to raise the white flag, Captain Patrick Dalton of the San Patricio Battalion tore it down. Taking his cue from the Irishman, Anaya ordered his men to continue the resistance, even if they had to fight with their bare hands.

Twice more Mexicans tried to raise the white flag, but according to some stories the San Patricios shot dead anyone who attempted to capitulate. Lt. Col. Francisco Penunuri of the Independencia Battalion tried a desperate bayonet charge against the Americans, but he was killed and the attack was unsuccessful. The San Patricios fought with the courage of desperation, but after the fall of the bridgehead American victory could not be long delayed.

Captain Edmund Alexander of the U.S. 3rd Infantry was the first over the convent rampart, and soon other followed. There was bloody fighting in the ancient rooms and corridors of the convent, with men wielding sabers and thrusting bayonets with wild abandon. All dissolved into chaos as the shouts and curses of the combatants mingled with the screams of the wounded and echoed and reechoed down the convent halls.

U.S. Army Captain James Smith raised his white handkerchief. This was done not to surrender but to make the Mexicans pause long enough for him to make a suggestion. He tactfully asked that the Mexicans at Churubusco capitulate, and this time the offer was accepted. Thirty-five men of the San Patricio Battalion were killed and 85 taken prisoner, including a wounded Riley.

Not all Mexicans surrendered; some managed to escape, including fewer than 100 men of the San Patricio Battalion. The American forces assaulting Churubusco had suffered approximately 1,000 casualties in the operation and were not in a forgiving mood when they finally met the captive San Patricio men face to face. It was said they “vented their vocabulary of Saxon expletives” on the captives.

Anaya was still defiant after surrendering. When the Americans asked where his ammunition was, he said, “If I still had ammunition, you would not be here.” Mexican losses totaled 700 killed and wounded and 1,800 captured.

Scott halted the pursuit of the retreating remnants of the Mexican army, which were falling back toward Mexico City. He could have taken the city, but he did not because he said he was willing “to leave something to this [Mexican] republic.”

The twin Battles of Contreras and Churubusco, which really were two phases of the same battle fought on August 20, constituted a Mexican disaster. In a single day, Santa Anna had lost 4,000 killed or wounded and an addition 3,000 captured. Among the prisoner haul were eight generals, two of whom were former presidents of Mexico.

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City “possessed of a black despair from the unfortunate events of the war.” Any other Mexican leader would have been discredited and more than likely swept from power; indeed, Santa Anna had already experienced a checkered career of ups and downs. But in truth there was no one else available with his charisma and ability to rebound from disaster. The peg-legged dictator remained in power, recovered his optimism, and suggested a truce.

Scott could have taken Mexico City at this time, but he halted operations and agreed to the truce. This was done for political, not military reasons. It was hoped that if their capital was not taken the Mexicans, honor and face intact, would be more willing to enter negotiations. Santa Anna, as wily and duplicitous as ever, used the truce to strengthen his defenses and rebuild his army. Scott resumed the offensive in early September when it was plain Santa Anna had no intentions of making a serious peace.

On September 8, Scott attacked Molina del Rey, which also was known as King’s Mill. He believed the structure contained a cannon foundry. The incident was one of Scott’s rare mistakes because the mill was heavily defended and the Americans should have bypassed it. They did take Molina del Rey, but at heavy cost. When the Americans entered the building, they found it did not contain any cannons.

Scott by then had reached Tacubaya, a village located about four miles from Mexico City, where stopped to explore his options. The city was far from helpless, and there were still a number of formidable defenses to overcome before the Americans could seize the prize. The first of these was the Chapultepec Castle, perched atop a 220-foot hill.

Chapultepec means “grasshopper hill” in the Aztec language. In 1775, Viceroy Bernardo de Galvez built a magnificent home for himself at the highest point of Chapultepec Hill. The stately home later was converted into a military school. The hill itself was about three-quarters of a mile wide, and a quarter-mile long. The north and east sides were quite steep. They were too precipitous for an assault with scaling ladders. The west slope had possibilities, but a walled garden and a tree-choked cypress swamp would hinder any advance.

Scott hoped Chapultepec might surrender by being subjected to an artillery bombardment alone. American batteries were placed in position, guns that included 16-pound siege guns, eight-inch howitzers, a 10-inch mortar, and a 24-pounder. Scott’s artillery opened fire at 5 am on the morning of September 12.

The bombardment was fairly light at first but gained in intensity as the morning wore on. The castle walls were breached in places, and heroic Mexican engineers did what they could to repair the damage even as new shells fell. The roof was partly destroyed, and Mexican casualties grew to such an extent a corridor was converted into a makeshift hospital. Wounded soldiers were piled together, their moans echoing through the building, but there were no medications to ease their pain.

In the end, Scott decided the Americans would mount a two-pronged attack on the castle. Pillow’s men would launch an attack on the western side. Quitman’s division would be on Pillow’s right on the Tacubaya Road, scaling the walls on that side. Each division would be spearheaded by a “forlorn hope” of 265 men each, all regulars. Some 50 Marines also would take part, the action forever immortalized by the Marine Corps hymn in the “Halls of Montezuma.”

The castle was commanded by Nicholas Bravo, a tough old soldier who was something of a legend in his own time. There were perhaps 260 men in the castle proper, including 50 young cadets. They were augmented by about 600 men posted around the walls that protected the castle.

Scott chose September 13 as the day to attack Chapultepec. It was a beautiful, clear day. The sky was a cobalt blue, and the surrounding snow-capped peaks stood out in sharp relief in the far distance. But Mexican resistance seemed to grow more determined the closer they came to the capital, and the small American army was far from home. Worth privately said, “We shall be defeated.” Even Scott had his misgivings.

After a preliminary bombardment, the American assault went forward. Lieutenant James Longstreet of the 8th Infantry was wounded, and Lieutenant George Pickett took the colors Longstreet had been carrying. The advance momentarily halted at the base of Chapultepec’s walls while scaling ladders were brought forward. American sharpshooters kept Mexican heads down while the attackers waited. The first few ladders placed on the wall were flung off by the defenders, even though they were heavily laden with soldiers and Marines clinging to the rungs.

Eventually more ladders were placed on the wall, enough to have 50 Marines and soldiers climb simultaneously. The Mexican wall defenders fell back for a last stand, and the subsequent hand-to hand fighting was short but bloody. A patriotic Mexican story tells of six cadets who refused to surrender. One of them, teenaged Juan Escutia, wrapped himself in the Mexican flag and plunged to his death from the high battlements.

Nothing could prevent the Americans from taking Chapultepec Castle. The American flag was raised, and General Nicolas Bravo Ruedo gave up his jeweled sword in token of surrender. The Americans were triumphant, but the city still was not in their possession. The city was protected by fortified gates, so there was no time to lose.

There were two roads, both of which were raised causeways above a boggy swamp that led from Chapultepec to Mexico City. The roads branched out, forming a “V.” They were fairly wide because each had an aqueduct running down its center with a road bed on either side. One led to Mexico City’s San Cosme Gate and the other to Belen Gate.

Lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant of the 4th Infantry was with those who pushed up the road to San Cosme Gate. He noted that the road and its aqueduct made a sharp right turn before reaching the gate itself. The aqueduct offered advantages as well as disadvantages. Although its arches offered protection for advancing American troops, they also gave Mexican defenders similar protection.

“At points on the San Cosme road parapets were thrown across, with an embrasure for a single piece of artillery each,” wrote Grant. There were also houses along the way, “covered with infantry and protected by parapets made of sand bags,” he wrote, adding that “deep, wide ditches, filled with water, lined the sides of both roads.” Worth’s command surged up the road to San Cosme, while Brig. Gen. John Quitman’s division advanced on Belen Gate.

Grant saw a church whose belfry commanded a view of the fortified San Cosme Gate and the territory just beyond. Quickly formulating a plan, Grant took a handful of artillerymen forward with a disassembled mountain howitzer. The Model 1841 fired a 12-pound shot and weighed 500 pounds with its carriage. The barrel alone, disassembled, was some 220 pounds.

Carrying the various components of the gun was no easy task since the sweating men had to cross some water-filled ditches. When Grant reached the church he pounded on its door seeking admission. A priest appeared, no doubt amazed at this strange apparition in a dirt-spattered dark blue coat. Grant spoke a little Spanish, and finally the priest reluctantly let the Yankees in.

The soldiers manhandled the gun pieces up to the belfry and then reassembled the howitzer as fast as they could. In no time, the howitzer was lobbing shot in the midst of the San Cosme Gate defenders, who were only about 300 yards away. The fire was so effective that the Mexican defenders were thrown into confusion. Grant’s gun and its handful of artillerymen did much to help open the San Cosme gate.

In the meantime, Quitman and his men had taken the Belen Gate and were entering the city. There was not going to be any last-ditch defense of the capital. In fact, as the Americans were coming in Santa Anna withdrew his army from the city. Santa Anna released several thousand criminals from the city’s jails in an apparent attempt to create chaos in his wake.

The Americans had the pride but not the panoply of their retreating foes. After several days of hard fighting, their blue uniforms were ragged, dirty, and bloodstained as they entered the capital. Quitman entered with only one shoe on. It was said a U.S. Marine raised the American flag atop the National Palace. Scott formally entered Mexico City the next day. There would be many months of wrangling before a formal peace treaty was signed, but Scott’s prediction had come true. The Splendid City was in American hands.

Where are the MAPS???