By William E. Welsh

Following the completion of Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s unsuccessful Peninsula campaign earlier in the month, General Robert E. Lee sent Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson north from Richmond with two divisions on July 16, 1862. Jackson arrived in Gordonsville three days later. On July 29, his army was reinforced by Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s “Light Division.” The reinforcements doubled Jackson’s command and gave him the strength necessary to overwhelm any one of the three Federal corps of the newly formed Army of Virginia under Maj. Gen. John Pope, which was spread along a wide arc from Fredricksburg to the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Pope, who had assumed command of the Army of Virginia on June 27, had been given the complex task of uniting three previously independent commands scattered widely over the northern half of the state into a single army. He ordered Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel’s I Corps to Sperryville, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’s II Corps to Little Washington, and one division of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s III Corps to Waterloo Bridge, leaving his other division at Fredricksburg to guard the lower Rappahannock River. In preparation for a raid on the vital railroad hub of Gordonsville, where the Virginia Central Railroad connected the Confederate capital of Richmond to the Shenandoah Valley and to Tennessee, Pope ordered Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford’s brigade south to Culpeper to support Federal cavalry massing for the raid. But when the Federals learned that Jackson was advancing from Richmond with a force of unknown size, their mission changed abruptly from raiding to reconnaissance. Pope needed information quickly about the size of Jackson’s force.

Jackson’s Orders: Three Divisions to the Orange Court House

The addition of Hill’s Light Division to his independent command gave Jackson the ability to overwhelm a portion of Pope’s army, just as he had done to his foe in the Shenandoah Valley a couple of months earlier, if he could strike the enemy before support could arrive. To do this, Jackson hoped to reach Culpeper before the Federals could secure it in order to control its vital road network. His first target would be Banks, who Jackson learned from his scouts recently had been ordered to Culpeper by Pope.

On August 7, Jackson delivered orders of his own to his three divisions to march eight miles from Gordonsville to the vicinity of Orange Court House. From there, he hoped to reach Culpeper the following day. When Federal scouts reported the movement to Pope, the Union general ordered Sigel’s corps and the rest of Banks’s corps to converge on Culpeper. Banks arrived on August 8, but Sigel did not arrive until the following day.

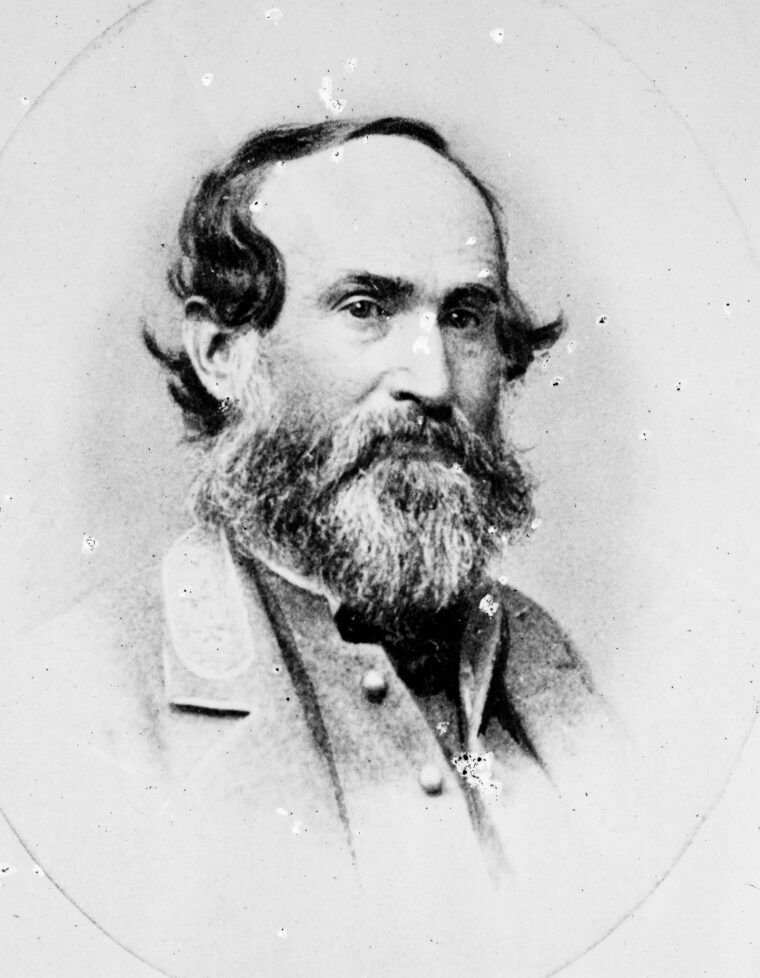

With the arrival of Hill’s division, Jackson had under his command about 24,000 men in three divisions. Hill’s 12,000-strong Light Division comprised six brigades, while Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell’s division and Jackson’s division, under Brig. Gen. Charles Winder, had 7,000 and 4,000 men, respectively. In addition, Jackson had Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson’s 1,000-strong cavalry brigade. The army was considerably larger than the one Jackson had commanded in the Shenandoah Valley earlier in the year. It would prove difficult for Jackson to manage, both on the march and on the field of battle. The campaign got off to a poor start when Jackson’s famous “foot cavalry” managed to march only a half dozen miles on August 8—not the 20 miles a day for which it was noted. Winder, who had been sick with a fever and under orders to rest, received Jackson’s permission to return to his command for the pending battle.

The Confederate Vanguard Arrives at Cedar Mountain

The August sun baked the Southerners as they marched north and showed no mercy to the troops, regardless of rank or branch of service. The narrow road was jammed with ammunition wagons, artillery, and ambulances. Thick clouds of dust filled the air, clogging men’s throats and eyes. Jackson rode with his cap pulled down to keep the sun from his eyes. To those who rode past him, he seemed preoccupied, as well he might be. The night before, Union cavalry had raided his bivouac, setting off a firestorm of musket fire at 3 in the morning. Jackson fretted constantly about the 1,200 wagons the army had rumbling along in its train. When his personal surgeon, Hunter McGuire, asked Jackson if he expected a battle that day, Jackson flashed the hint of a smile. “Banks is on our front, and he is generally willing to fight,” said Jackson, adding in an aside, “and he generally gets whipped.” Then he fell silent again.

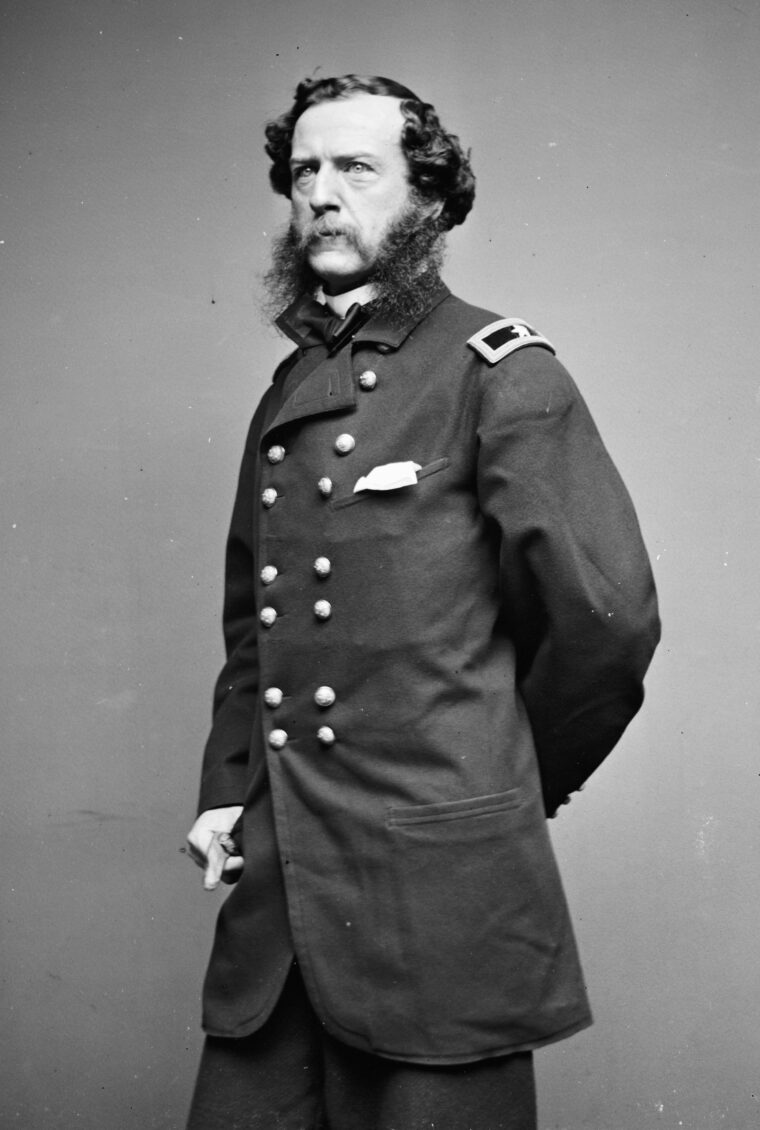

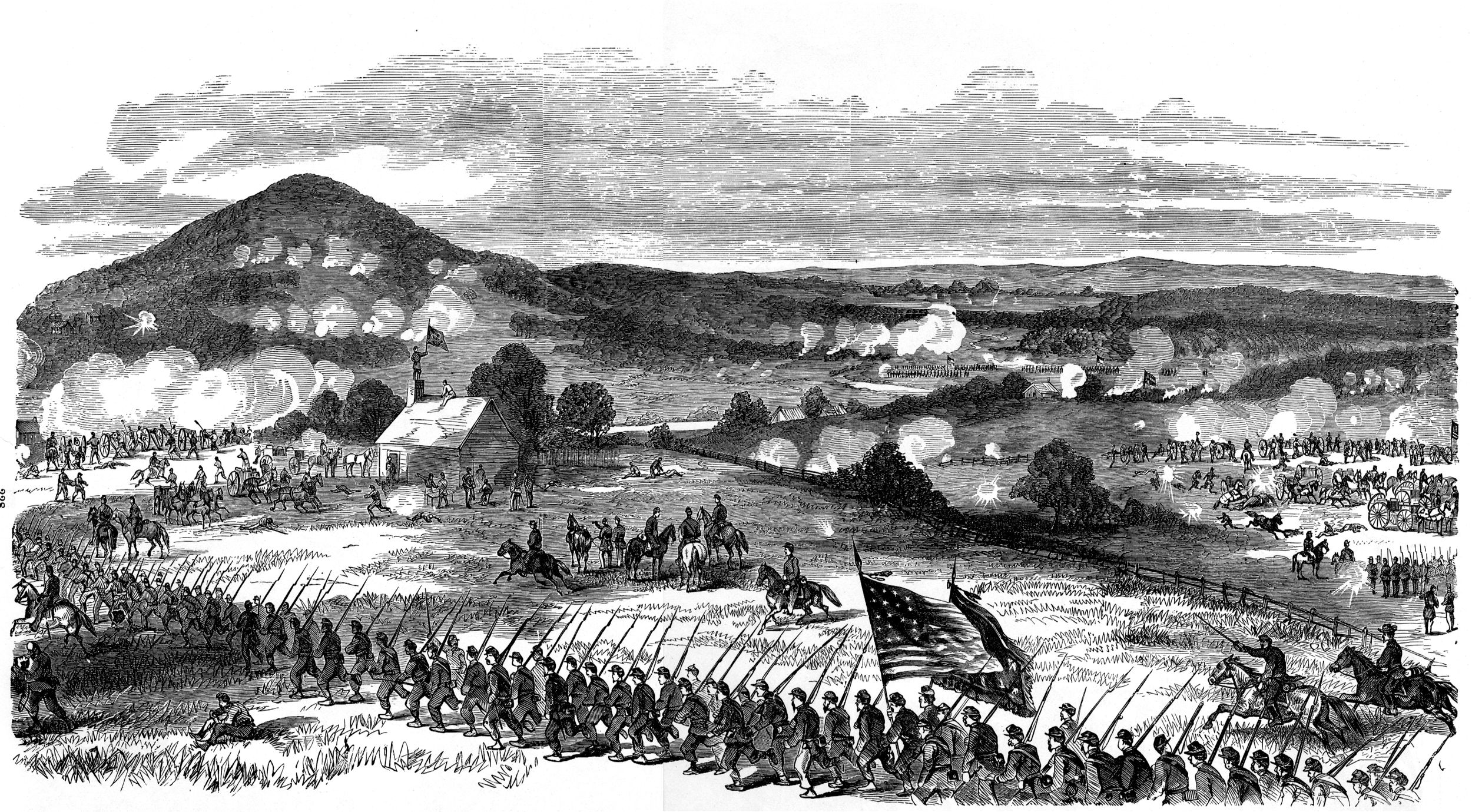

While the Confederate commander fretted, the enemy began to move. Samuel Crawford, a brigadier with a solid record that stretched back to the opening days of the war, left Culpeper at noon on August 8, taking with him two batteries to support the Federal cavalry operating south of the town. On August 9, the rest of Banks’s corps, roughly 8,000 men, joined Crawford on the high ground between the two branches of Cedar Run. The five Federal brigades deployed in line of battle along a two-mile front to await the Confederate attack.

Banks, a former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and governor of Massachusetts, was considered by his contemporaries to be an aggressive general. He had been soundly whipped a few months before by Jackson in the northern Shenandoah Valley, and he was looking to even the score. Despite Pope’s warning to wait for reinforcements, Banks had no intention of staying on the defensive if an opportunity should present itself to strike Jackson a hard blow. The fact that he had stationed his troops in line of battle astride the Culpeper Road was intended as a direct challenge to his foe. That was not at all what Pope had in mind, but Banks had a mind of his own.

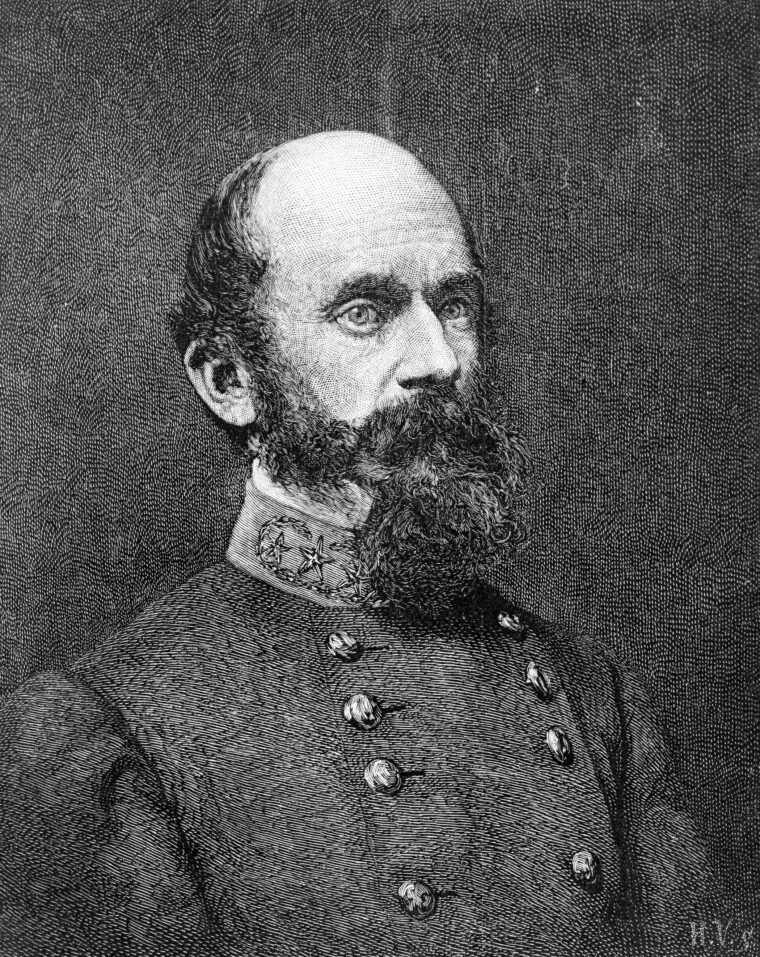

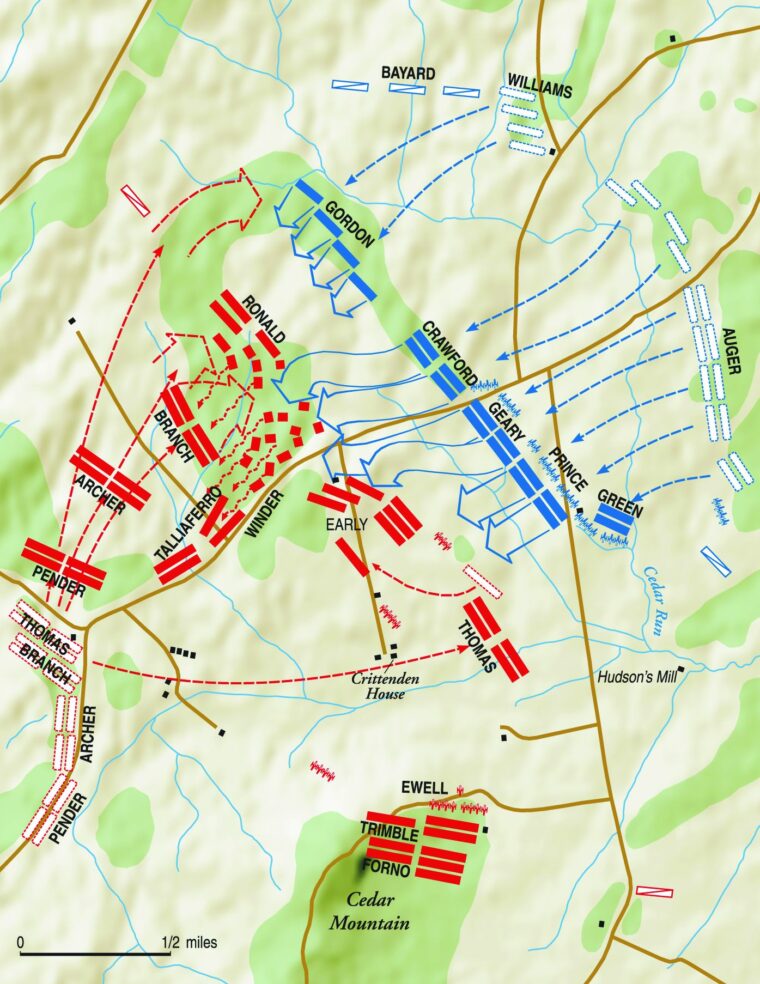

The Confederate vanguard, composed of the three brigades of Ewell’s division, arrived at Cedar Mountain (also called Slaughter’s Mountain, after Revolutionary War captain Phillip Slaughter) in the early afternoon, but it would be several hours before the Confederates were deployed in an effective line of battle. Brig. Gen. Jubal Early deployed his Confederate brigade in the fields of the Crittenden farm south of the Culpeper Road. Early pushed out a skirmish line, accompanied by a brace of 12-pounder cannons, and sent the Union pickets flying. He headed toward the intersection of Culpeper Road and Madison Court House Road, just west of the mountain.

Plenty of Challenges Await for Early

Federal artillery opened up on his troops from Mitchell’s Station Road, which ran perpendicular to the Culpeper Road. The feisty Early, still aching from a shoulder wound he had suffered at Fort Magruder a few weeks earlier, would have to fight alone while Ewell took the other two brigades of his division along the base of Cedar Mountain. The two brigades traveled undetected on a road through the woods. Their objective was to seize the high ground at the eastern end of the mountain. When Ewell reached the eastern edge of the mountain, he placed parts of two batteries on the commanding hill.

Because the units were nearly a mile apart, Early would have to rely on his own wits and the two other Confederate divisions for support. He personally led a reconnaissance party that located an old farm lane that diverged from the main road and spilled out into the woods directly onto the farmland where the Union cavalry was forming. As Early’s men crept through the woods, Confederate artillery opened up on the unseen Federals who lay beyond the rolling farmland. The Federals responded with a splendid salvo of counterfire that showered the choleric Early with dust. By 3 pm, Early was in position and awaiting the deployment of Jackson’s division, under Winder.

Before deploying his infantry, Winder placed his batteries just south of the Culpeper Road, near the gate that marked the entrance to the Crittenden farm. As his brigades arrived on the battlefield, Winder sent them forward one at a time. First, he sent Colonel Thomas Garnett’s brigade into the woods bordering a large wheat field immediately north of the Culpeper Road. Next, Winder directed Brig. Gen. William Taliaferro’s amalgamated Virginia and Alabama brigade south of the turnpike to support Early’s left flank. Lastly, he ordered Colonel Charles Ronald’s brigade, the Stonewall Brigade of First Manassas fame, through the woods north of the road to take up positions on Garnett’s left flank.

Ronald’s Early Failure Nearly Cost the Confederates Everything

While Garnett and Taliaferro executed their orders admirably, Ronald wound up far beyond and behind Garnett’s left flank. The Stonewall Brigade came to a halt in a tree line on the western end of a smaller field north of the one upon which Garnett was positioned. The “brushy field,” as it is referred to in contemporary accounts, was not where Winder had wanted the unit placed. Ronald’s failure to effectively carry out Winder’s orders nearly cost the Confederates the battle almost before it started.

Banks deployed Brig. Gen. Christopher Auger’s division, comprising three brigades, south of the Culpeper Road, and Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams’s division, consisting of two brigades, north of the road. The Federal right flank overlapped the Confederate left flank by nearly 300 yards. Both Jackson and Winder were unaware that the wooded ground north of the Culpeper Road presented a golden opportunity to the Federals to outflank the Confederates if they could attack before Jackson was able to extend his line.

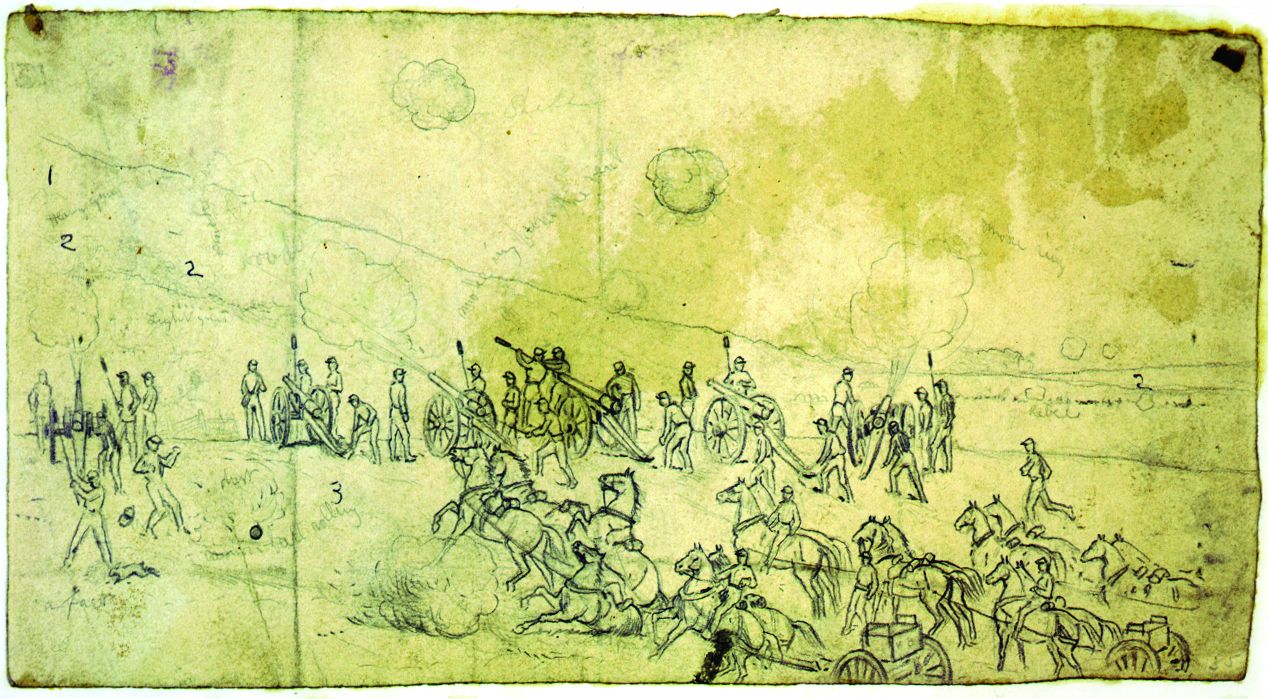

As Jackson awaited the arrival of Hill’s division before committing himself to battle, the two opposing sides engaged in a ferocious artillery duel. Beginning at about 4 pm, the Union and Confederate gunners dueled for nearly two hours across open ground from 900 yards apart. Unlike the Federal guns, which were concentrated near the intersection of the Culpeper Road and Mitchell’s Station Road, the Confederates had deployed their guns in four separate positions between the Culpeper Road and Cedar Mountain. The placement of the Southern guns in clusters allowed them to bring a converging fire on the Federal batteries that was so effective the Northerners had to withdraw their guns more than once during the duel. Still, the Federal guns slowed the pace at which the Confederate infantry could deploy and substantially delayed Jackson’s advance.

Once the artillery contest was in full swing, the ailing Winder became engrossed in the exchange to the detriment of his division. At one point, he ordered Garnett to prepare to charge across the open ground in front of Early to seize the Federal battery he believed was unprotected. To carry out these orders, Garnett was forced to face two of his regiments south along the Culpeper Road, rather than east toward the Federal infantry on the opposite side of the wheat field. This further weakened the Confederate left flank. Although he complied with the order, Garnett sent word back to Winder that the enemy guns could not be taken because they were supported by both infantry and cavalry. Instead of sorting out the problem, Winder ordered Garnett to keep the regiments aligned as instructed, and he turned his attention back to the artillery contest.

A Fatal Wound for Charles Winder

While Winder was directing the artillery fire near the Crittenden gate, a shell came whistling down from one of the Federal batteries and struck him on the left side, nearly tearing off his arm at the elbow. The general quivered and dropped to the ground with what was described as “a tremendous hole in his side.” A surgeon examined his wounds and deemed them fatal. Winder was carried on a stretcher to the rear, where he died less than two hours later. Jackson, hearing of the incident, raised his arm and bowed his head for a moment of silent prayer.

The wounding of Winder at 4:45 pm meant that Taliaferro would now assume command of Winder’s division. The task that Taliaferro inherited was a difficult one. Neither Winder nor Jackson had apprised him of their orders. What was more, Taliaferro began receiving reports that Federal troops were massing opposite the Confederate left flank. He personally inspected his left on horseback, but found no evidence of an impending attack. Jackson, who was devoting most of his time to the situation south of the Culpeper Road, also inspected the left flank. Before riding away, Jackson told Garnett to watch his left flank closely and, if necessary, request support from Taliaferro.

While the Confederates were busy correcting the kinks in their deployment, the Federals south of the Culpeper Road attacked. Leaving behind Green’s understrength brigade, Auger sent Brig. Gen. John Geary’s and Brig. Gen. Henry Prince’s brigades forward at 5:45 pm against the Confederate right flank. Banks watched intently from just north of the Culpeper Road as his blue ranks were swallowed up by the mature corn growing on the Crittenden farm. Across the field, Jackson sat atop his horse next to Taliaferro’s position. As the Federals approached, Jackson rose in his saddle and watched closely to see how his soldiers would meet the enemy attack.

The forces facing each other on the Crittenden farm were nearly equal. The Federals fielded 10 regiments and one battalion; the Confederates matched the attackers with nine regiments and a battalion. Geary’s brigade advanced on the right toward Taliaferro, while Prince’s brigade advanced on the left toward Early. Auger was struck in the back by a bullet in the first few minutes of the attack and carried to the rear. Geary advanced first with two regiments forward and another two regiments in reserve. Prince’s brigade attacked in the same style.

Early Gained the Support He Needed; Jackson’s Left Began to Waver

As the fighting grew in intensity, Early sent word to Jackson that he needed reinforcements quickly in order to hold back the Federals. In response to the Federal advance, Ewell’s guns on Cedar Mountain switched their attention from the enemy artillery to the Federal infantry on the plain below. When Early’s messenger arrived, Jackson sent a courier to Hill urging him to hurry forward with his troops. Help was not far away. Edward Thomas’s brigade had been marching at the double quick for the last mile of their 10-mile march that day. When the Georgians came pounding up the Culpeper Road, Jackson rode to meet them, hailing them as they arrived by waving his cap above his head. The Georgians responded with a loud cheer before moving to Early’s support.

Just when Jackson had stabilized his right, his left became unglued. From his position near Early’s brigade, Jackson’s attention was drawn to loud rolls of musketry to the north. He tried to see what was unfolding through his field glasses, but his line of sight was blocked by both the rolling terrain and thick woods. When a courier told him his left had been turned, Jackson spurred his horse and galloped back up the Confederate line. Fearing the worst, he began ordering to the rear the rifled artillery near the gate where the farm road exited the Culpeper Road.

Meanwhile, Crawford’s Federal brigade lay concealed for most of the hot August afternoon in the woods along the banks of Cedar Run, where it could not be seen by the enemy units forming up on the Confederate left. Just before dusk, when the length of the men’s shadows on the ground exceeded their height, some 1,500 Union troops emerged from the woods and prepared to advance across a stubbled wheat field to engage their foe. They dressed ranks, crossed a fence, and with a loud cheer rushed downhill toward the Confederate line. To the Virginians of Garnett’s brigade, which occupied a nearly identical wood on the opposite side of the wheat field, the attacking blue line seemed to extend indefinitely in both directions.

A Roar of Musket Fire from Garnett’s Confederates

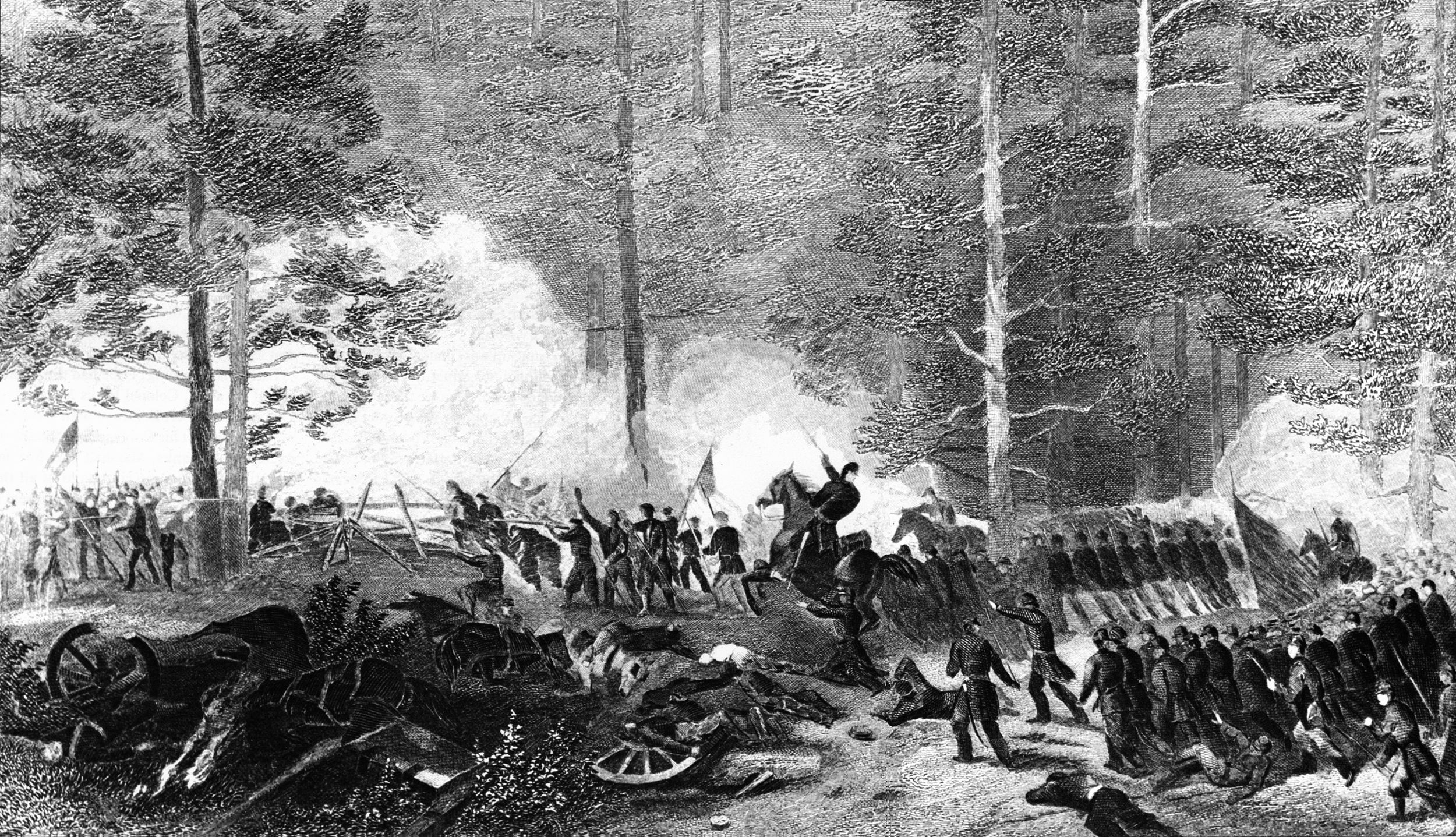

Before Crawford’s brigade had advanced halfway toward its objective, the first of several volleys erupted from Garnett’s Confederates. The musket fire soon became one continuous roar, like a never-ending peal of thunder. The Federals continued to advance despite the storm of lead, pausing briefly at the tree line before closing with their enemy. Soldiers swung their rifles like clubs and thrust at each other with bayonets. Although the Confederates occupied what appeared to be a strong position along a fence line, the Union soldiers prevailed.

Crawford’s brigade had the good fortune of finding the Confederate left flank in the air. The Stonewall Brigade was farther to the left, but it had not yet advanced to the wheat field. Worse yet, two of Garnett’s regiments were not even facing in the direction of the attack. The 1st Battalion of Garnett’s brigade reacted to the Federal attack like a man bitten by a rattlesnake. Panic spread from one soldier to the next. Dozens fell alongside the fence in a matter of minutes. In no time, the Federals were over the fence and chasing their enemy through the woods. A number of the soldiers in the 1st Battalion simply dropped their rifles and fled without looking back. The Federals changed front to the east and rolled down the line in the direction of the 42nd and 48th Virginia Regiments. To stem the blue tide, these units would have to hold, and the Confederate command would have to rush reinforcements to the spot. Otherwise, the day would belong to the Federals.

By taking Garnett’s brigade in the flank, Crawford was able to multiply the effect of his attack manyfold over a frontal attack. His objective had been the guns near the Crittenden gate that Jackson had so wisely sent to the rear. Even though the guns were now safe, Jackson’s entire line was slowly unraveling. Jackson wrote after the battle that the Federals “fell with great vigor” on his left flank. Unless he stabilized it, his army was on the verge of a major disaster.

Hand-to-Hand Fighting in the Woods

The Federals steadily drove their enemy before them. The 28th New York advanced on the right, while the 5th Connecticut advanced on the left. Interspersed with these regiments were elements of the 46th Pennsylvania. While the Confederate 1st Battalion had fled without much of a fight, the 42nd Regiment stood its ground until fire from both the front and rear forced it to retreat as well. The 21st Virginia and 48th Virginia, which were facing south along the Culpeper Road, were the unluckiest of all. They did not discern what was happening until some of their numbers were shot in the back. Still, they tried valiantly to fend off the attack. The two sides fought hand to hand in the thick woods. Soon, Garnett’s entire brigade was routed.

When the Stonewall Brigade finally advanced, it caught the rear elements of Crawford’s attack in the flank. Two regiments of the Stonewall Brigade formed along the fence line bordering the wheat field across which Crawford attacked, while the remaining three regiments advanced through the brushy field next to it. These three regiments wheeled to change front before firing into the 3rd Wisconsin, which had been detached from Brig. Gen. George Gordon’s brigade and assigned to Crawford.

Crawford’s Troops Charge Talaiferro’s Brigade

Crawford’s troops poured out of the woods, crossed the Culpeper Road, and charged Talaiferro’s brigade. They quickly routed two green Alabama regiments on Taliaferro’s left flank. The other regiments fell back but continued fighting. Early, who had just finished placing Thomas’s Brigade on his far right flank, galloped over a ridge and found half his brigade gone. The Confederate line stabilized temporarily when four well-served guns of the Middlesex Artillery under the command of Captain Willie Pegram fired canister at point-blank range into the Yankee tide. Shortly afterward, Crawford’s attack ran out of steam. Meanwhile, Jackson found Hill and ordered him to deploy the rest of his division immediately. The troops of Brig. Gen. Lawrence Branch advanced first and were soon followed by those of Brig. Gen. James Archer.

Leaving Hill to do as he had been told, Jackson rode to the Crittenden gate, where he found large numbers of men from Winder’s division seeking protection in the woods south of the Crittenden gate. Oblivious to personal danger, Jackson rode into the mass as bullets flew around him. In an effort to rally the men, Jackson tried to draw his sword, but found it rusted in its scabbard. He unhooked it from his belt and waved the scabbard in an effort to get his men to reform. Thinking that this was not enough, he snatched a Confederate battle flag and began beseeching the men to fight with his scabbard in one hand and a Confederate battle flag in the other. “Jackson is with you!” he cried. “Rally, brave men, and press forward! Your general will lead you! Jackson will lead you! Follow me!” When only a few dozen men stopped, he yelled: “Rally men! Remember Winder! Forward, men, forward!” Jackson was able to form parts of Garnett’s and Taliaferro’s brigades into a new line. At that point, Taliafferro rode over to Jackson and implored him to retire. “Good, good,” Jackson said in his usual taciturn manner, before riding to the rear.

Banks failed to follow up Crawford’s attack with reinforcements, even though Gordon’s brigade, the other brigade in Williams’s division, had not yet been committed to the battle. Without support, the survivors of Crawford’s attack had no choice but to retreat along their line of attack. There followed a series of inept moves by Banks and his subordinates. The first was the advance of the 10th Maine. The regiment, which had been detached from Crawford’s brigade to guard a Federal battery, was sent alone into the wheat field at about 6:30 pm, where it was sacrificed to no clear advantage. Next, Banks unnecessarily sacrificed the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry to cover the withdrawal of his artillery, losing 93 horsemen in the futile charge.

Archer Rallies His Troops Under Fire from the Woods

At dusk, Gordon’s brigade arrived opposite Archer, but it was too late to help Crawford. Gordon’s men had marched nearly a mile to the battle at the double-quick. Their effectiveness was greatly reduced by the difficulty they had telling friend from foe in the wheat field in the gathering darkness. As Gordon’s men were deploying, the men of the Stonewall Brigade descended on Crawford’s brigade as it limped back across the wheat field. The 5th Virginia charged across the open ground and plucked from the retreating troops the flags of the 5th Connecticut and 28th New York. When Brig. Gen. Dorsey Pender’s brigade, another of Hill’s fresh brigades, joined Branch and Archer on the Confederate left flank, Gordon’s brigade found itself in great peril.

Jackson issued orders directly to both Pender and Branch. He sent Pender through the woods behind the Confederate left flank and then turned east toward the Federals. He ordered Branch to incline right across the Culpeper Road to strike the Federals south of the road. While Branch was crossing the lane, Archer launched a frontal assault on Gordon. Archer’s men wavered midway to their objective. The brigadier general noted in his battle report that his command “was exposed to a heavy fire from the enemy, who, from their position in the woods, was comparatively safe.” Nevertheless, he rallied his troops in the open field and ordered them a bayonet charge against the Union position.

The effect of Archer’s attack was vividly described in Gordon’s battle report: “Companies were without officers, officers and men were falling in every direction from the fire of an enemy which largely outnumbered my brigade.” The brigade held its ground until Pender struck. Under cover of the woods, Pender was able to approach to within a few dozen yards of the enemy. “I met the enemy, repulsing him with heavy loss in almost the first round,” Pender wrote. The combined force of Archer and Pender was more than Gordon’s brigade could stand. With Pender in his flank and rear, Gordon ordered a general withdrawal. “The enemy poured a destructive fire in this new direction. It was too evident the spot that had witnessed the destruction of one brigade would soon in a few minutes be the grave of mine,” Gordon wrote.

Jackson Effectively Took the Initiative

The Federals were not only being pressed hard on their right and center but also on their left by Ewell’s descent from Cedar Mountain. The presence of the Confederates on the Federal left flank was enough to create a near stampede among the Union troops in that sector. Artillery crews hastily limbered up their guns and moved them north in the direction of Culpeper. They were followed by Brig. Gen. George Greene’s brigade of Christopher C. Augur’s division, which had been held in reserve throughout the battle. By sunset, eight Confederate brigades had entered the cornfield, leaving just Pender and Archer north of the Culpeper Road.

As the moon rose in the night sky, Jackson pushed two reserve brigades of Hill’s Division and substantial artillery up the road toward Culpeper. But Pope had already arrived on the battlefield and constructed a strong new line with fresh troops from Maj. Gen. James Ricketts’ division of McDowell’s corps. After a “reconnaissance by artillery” proved that the Federals held the road in strength, Jackson broke off his advance near midnight. After drinking a glass of buttermilk to calm his stomach, Jackson stretched out on a cloak strewn across the ground and immediately fell asleep.

Jackson waited for two more days after the battle to see if Pope would attack him. When he did not, Jackson withdrew to Gordonsville. The Union lost about 2,400 men at Cedar Mountain, while the Confederates lost close to 1,400. Both Jackson and Banks were satisfied with the performance of their troops on the battlefield. Jackson had achieved a tactical victory by driving the Federals from the battlefield, but he had suffered a strategic defeat by failing to capture Culpeper and annihilate Banks when he had the chance. But even though Pope had won a strategic victory, Jackson had effectively snatched the initiative from him at Cedar Mountain, and Pope would not regain it again during the Second Manassas campaign that followed less than three weeks later.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments