By Michael Hull

Everyone who was alive on that fateful Sunday morning remembers it all too clearly, and those born later are well aware of what befell the U.S. Pacific Fleet and shore installations in Hawaii. It has been told and retold.

As if it had not been dealt with fully enough, the 60th-anniversary year has brought a new word-and-picture deluge about the defining event that thrust a woefully unready America into World War II. There have been some creditworthy new books, along with some reissues of previous works.

Part of the fascination with Pearl Harbor lies in unanswered questions that lurk in some minds, thanks to the efforts of certain revisionist historians who have advanced theories of top-level conspiracy. It has been suggested that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, aided and abetted by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, somehow engineered the Pearl Harbor attack in order to push America into the war. But there is no evidence for this.

FDR and Churchill were just as shocked as everyone else on December 7, 1941, and it was not in the makeup of either man to deliberately sacrifice innocent lives.

It is true that Churchill, whose nation was struggling alone against the Axis countries, dreamed of America standing beside him, and it is true that Roosevelt knew his country would not survive for long in a world dominated by fascists. But, while bending neutrality laws to aid Great Britain, which he saw then as America’s only course in defense of freedom, FDR was looking toward Europe and not the Pacific.

It is true that Churchill, whose nation was struggling alone against the Axis countries, dreamed of America standing beside him, and it is true that Roosevelt knew his country would not survive for long in a world dominated by fascists. But, while bending neutrality laws to aid Great Britain, which he saw then as America’s only course in defense of freedom, FDR was looking toward Europe and not the Pacific.

The conspiracy-obsessed revisionists who have shrouded the Pearl Harbor tragedy in fanciful theories and myths take a severe beating in Stanley Weintraub’s Long Day’s Journey into War (The Lyons Press, New York, 2001; paper; 716 pp.; 39 photographs; 3 maps; $19.95), which is probably the best Pearl Harbor book to appear in recent years.

Weintraub, a meticulous scholar and master historian, categorically denies that the attack was the poisonous fruit of guilty foreknowledge, the result of devious wheeling and dealing by “That Man in the White House.” FDR, he writes, needed a war—and hoped for a war—because he knew that Adolf Hitler’s Germany had to be stopped. But, while Roosevelt realized that Japan’s day would come, he was hardly prepared for a war on two fronts.

Likewise, Weintraub dismisses the revisionist allegation that Churchill learned from JN-25, the Japanese naval code, of designs on Pearl Harbor, and that he withheld the data from FDR in order to plunge America into the war. In fact, Churchill and his top planners were genuinely surprised, though openly relieved, when news of the attack came.

Roosevelt’s military chiefs knew that Japan was about to strike, but not where, says the author. The complex Japanese naval code labeled AN-1—superseding JN-25 and supplemented in August 1941—might have pinpointed places and times of attack for American cryptographers, but none of the 7,000 Japanese messages a month flooding into Washington from intercepts had been deciphered by December 7. Coded orders flashed to the Japanese fleet in October-November 1941 were not cracked until 1946.

The failure to get a timely alert out to Pearl Harbor and all other possible military targets was due, says Weintraub, to interservice rivalry and laxity in Washington rather than to enemy chicanery or Rooseveltian duplicity. A “war warning” was sent to all commands by General George C. Marshall, Army Chief-of-Staff, on November 27, 1941, but recipients read into it only concerns about sabotage.

The author indicts Emperor Hirohito, who maintained after the war that he was only informed of military plans after they were irreversible. In fact, he attended planning conferences, and his chief adviser, Koichi Kido, sat in when the emperor could not be present. The minutes of imperial conferences record his pleasure at the outcome of December 7, 1941, and not the misgivings he confided later when faced with the possibility of being tried as a war criminal. His innocence was a myth, says the author.

Weintraub downplays the suggestion that America provoked Japan by withholding war materials. Japanese aggression in the Far East was already under way, he points out, and the militarist government in Tokyo had printed and stockpiled occupation currency for the countries it intended to invade, including the Philippine Islands.

There would have been no stopping the Japanese military machine, seasoned by a decade of campaigning in China, even if a negotiated delay had been operative in November 1941.

As it so happened, Pearl Harbor proved to be Japan’s undoing, and she lost the war in the first hour. By awakening the sleeping giant, she faced a war she could not hope to win. The raid swept away the climate of isolationism and apathy that was suffocating America and united her people. A massive revulsion erupted against the Japanese, and it was suddenly a nonnegotiable fight to the finish.

What makes Weintraub’s book unique is that he has constructed an hour-by-hour mosaic of the whirlwind events—military, diplomatic, political—that swept the globe on December 7, 1941. The scenes shift dramatically from Battleship Row to Washington, from Wake Island to Tobruk, from Singapore to Leningrad, from Manila Bay to Cape Town. It is a stunning feat of historical narrative, placing Pearl Harbor in the full context of its turbulent time.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Day of Infamy by Walter Lord, Owl Books (Henry Holt & Co.), New York, 2001; paper; 243 pp.; 50 photographs, maps; $14.00.

It was a quiet, restful Sunday afternoon when most Americans were tuning in their radio sets—to either a Station WOR broadcast of the Dodgers-Giants football game at the Polo Grounds in New York or a New York Philharmonic concert at Carnegie Hall.

Both broadcasts were interrupted by news bulletins: The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. The majority of Americans had no idea where Pearl Harbor was, but all would remember that day. Their lives, and the fate of their country, would be changed forever.

The story of December 7, 1941—with all its tragedy, sacrifice, and courage—unfolds vi-vidly and at a rapid pace in Walter Lord’s page-turning best- seller. First published in 1957, it has lost none of its immediacy, its sweep, or its impact.

He is a relentless researcher, deft organizer, and master storyteller, as proved in his other acclaimed works on the Titanic sinking, America’s entry into the 20th century, the battles of Dunkirk and Midway, and the Australian coastwatchers of the Solomon Islands.

Day of Infamy brilliantly interweaves historical scholarship and intense human drama.

Pearl Harbor: America’s Call to Arms, Robert Sullivan, ed.; Time Life Inc., New York, 2001; paper; 128 pp.; photographs, maps, graphics, $9.99.

Pearl Harbor: America’s Call to Arms, Robert Sullivan, ed.; Time Life Inc., New York, 2001; paper; 128 pp.; photographs, maps, graphics, $9.99.

Young people discovering American history and finding themselves intrigued by the Japanese sneak attack that propelled America into World War II could do a lot worse than leafing through this vivid and attractive volume.

Rich with stunning photography and detailed graphics, it presents a dramatic panorama of Hawaii both at peace and under attack. Many of the photographs are familiar, but some have not been widely seen before.

Pearl Harbor includes some reminiscences by survivors; a brief section on the USS Arizona Memorial; and a chapter showing how Hollywood has portrayed Pearl Harbor, from Fred Zinnemann’s 1953 milestone, From Here to Eternity, to this year’s Pearl Harbor.

While the text is rudimentary, it is nevertheless crisp and adequate for anyone wishing to learn about the day of infamy and the mood of America. The brief introduction is by the distinguished television journalist, Hugh Sidey.

Day of Deceit by Robert B. Stinnett; The Free Press, New York, 1999; hardcover; 386 pp.; 42 photographs; $26.00.

Day of Deceit by Robert B. Stinnett; The Free Press, New York, 1999; hardcover; 386 pp.; 42 photographs; $26.00.

While helping to buttress the beleaguered British in 1940-1941, and knowing that it was only a matter of time before his nation was drawn into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt believed that his peace-loving countrymen would react only to an overt act of war against the United States.

So he decided, in concert with his advisers, that the only course of action open to him was to provoke Japan. At the center of his plan, as revealed in Stinnett’s gripping and disturbing book, was one Lt. Cmdr. Arthur H. McCollum, head of the Far East desk at the Office of Naval Intelligence. Drawing upon 16 years’ research and long-suppressed Navy files, the author shows in meticulous detail how McCollum’s eight-point plan for the Pacific area became the blueprint for FDR’s policy toward Japan.

The most shocking proposal called for the deployment of U.S. warships within or adjacent to Japanese territorial waters. There were three such “pop-up cruises,” as FDR termed them, between March and July 1941, and no shots were fired or lives lost.

Roosevelt faced “an agonizing dilemma,” and the author believes that he was forced to act the way he did. The Pearl Harbor attack was, from the White House perspective, something that had to be endured in order to stop a greater evil, Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

This is no revisionist book replete with sensational theories, but a scholarly, literate, and thoughtful study. Stinnett has done his homework.

The truths revealed here, he points out, do not diminish FDR’s “magnificent contributions to the American people.” Rather, the real shame of Pearl Harbor lies with the federal stewards who have kept the full truth under lock and key for more than half a century.

At Dawn We Slept by Gordon W. Prange; Penguin Group, New York, 1991; paper; 890 pp.; 36 photographs, maps; $20.95.

At Dawn We Slept by Gordon W. Prange; Penguin Group, New York, 1991; paper; 890 pp.; 36 photographs, maps; $20.95.

Pearl Harbor has been widely judged an intelligence failure, but Gordon W. Prange believes that it was less a failure of intelligence than a failure to evaluate properly the excellent intelligence available.

In no small way, he says in this exhaustively detailed and authoritative chronicle, mutual misunderstanding triggered the day of infamy. The Japanese believed the Americans to be decadent, soft, politically divided, and willing to settle for a negotiated peace. The Americans consistently underrated the Japanese people, their economy, armed forces, warships, and their willingness to take on a first-class power.

Hence, despite the plans, reports, war games, and strategic projections (some dating back two decades), the testimony of U.S. officers reveals that not one of them actually expected such a strike as was inflicted on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941. American authorities, says the author, were blinded by the obvious, for Japan had made no secret of her designs on the Far East.

The Americans assumed correctly that Japan could not win a sustained war against the United States (as Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, was well aware). What the Americans failed to consider, Prange points out, was a lesson of history: a so-called “have-not” nation may well possess a will and skill far exceeding her available resources.

Of the mistakes made by U.S. military authorities in 1941, the author believes that many can be boiled down to a failure to communicate. All along the line, he says, there was a failure to supply relevant information to juniors, a failure to spell out clearly what was meant, a failure to ensure that directives were understood and complied with, and the failure of juniors to be sure that they understood their superiors.

The Pearl Harbor saga—hour by hour and from both the American and Japanese perspectives—has never been studied more fully, intelligently, and evenhandedly than in this book, which will stand as a standard reference for many years to come. First published in 1981 by Prange in collaboration with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, it is literate, diligent, and gripping.

Battleship Arizona by Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 1991; hardcover; 405 pp.; 370 photographs; drawings; $65.00.

Battleship Arizona by Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 1991; hardcover; 405 pp.; 370 photographs; drawings; $65.00.

Wearing a derby, 32-year-old Assistant Navy Secretary Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived at the New York Navy Yard on the morning of March 16, 1914, for the keel-laying of a new warship.

She would be America’s 41st dreadnought, and was known then simply as Battleship No. 39. Eventually, she would be christened USS Arizona and commissioned in October 1916, her quarter-century of service being brought to an abrupt, fiery end at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Today, lying with 1,177 of her crewmen beneath a 184-foot-long enclosed bridge off Ford Island, the Arizona serves as a poignant memorial to all the servicemen who died during the Japanese sneak attack.

In this sumptuously detailed and lavishly illustrated volume, Naval Institute editor-writer Paul Stillwell tells the full history of the gallant ship that came to symbolize the tragedy and sacrifice of Pearl Harbor.

Stillwell includes a chronology of the Arizona’s cruises, much human detail about her crew, including touching letters written to his wife by doomed Machinist’s Mate Bill Woodward, and a chapter on the Arizona’s role in Lloyd Bacon’s Here Comes the Navy (1934) starring James Cagney, Pat O’Brien, Gloria Stuart, and Frank McHugh.

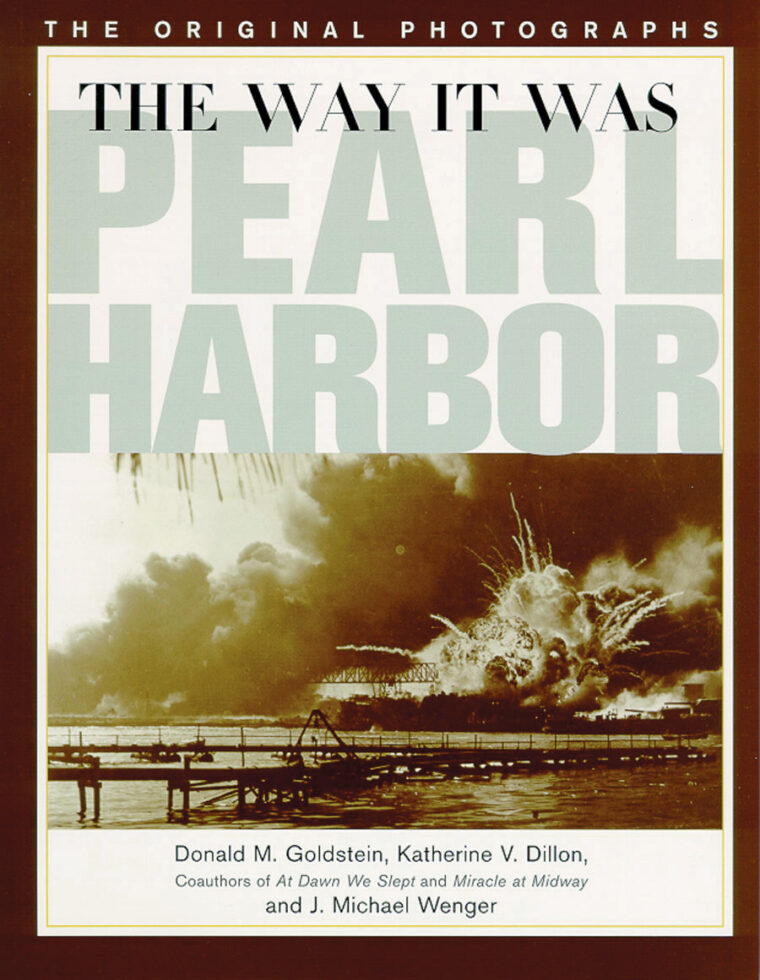

The Way It Was: Pearl Harbor by Donald M. Goldstein, Katherine V. Dillon, and J. Michael Wenger, Brassey’s Inc., Dulles, Va., 1991; hardcover; 182 pp.; photographs, maps; $19.95.

The Way It Was: Pearl Harbor by Donald M. Goldstein, Katherine V. Dillon, and J. Michael Wenger, Brassey’s Inc., Dulles, Va., 1991; hardcover; 182 pp.; photographs, maps; $19.95.

Few military engagements have been so thoroughly captured on film as the Japanese carrier-plane attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941.

Indeed, everyone present on that fateful Sunday morning with access to a camera seems to have been busily snapping away as the Zeros, Kates, and Vals swooped, and Battleship Row burned furiously. The result is this highly dramatic collection of original photographs—a unique historical record.

The artwork depicts the American and Japanese protagonists, the ships, the installations, and the planes—and follows the attack itself: the Japanese task force underway in heavy seas; fires, explosions, towering smoke columns engulfing the battlewagons and cruisers—“lined up like ducks in a shooting gallery”—around Ford Island; the furious curtain of antiaircraft fire that went up during the second-wave attack; and the widespread destruction inflicted, from army airfields and navy bases to the streets of Honolulu.

Accompanied by a crisp, knowledgeable text, The Way It Was is a stunning portrait of the day when America—rudely awakened and pitifully unready, yet swiftly angered—went to war.

Air Raid: Pearl Harbor!, Paul Stillwell, ed., Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 1981; hardcover; 299 pp.; 241 photographs; $39.95.

Air Raid: Pearl Harbor!, Paul Stillwell, ed., Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Md., 1981; hardcover; 299 pp.; 241 photographs; $39.95.

Everything that happened on the morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, is brought into sharp and poignant focus in this anthology of eyewitness accounts.

It is a rich, unique, and poignant historical record of the day as 47 men and women—both American and Japanese—recount their experiences, from Hawaii to Washington, from Manila to Tokyo. Almost half of the reminiscences are published here for the first time.

An officer from the USS Oklahoma wonders why he was spared when so many of his shipmates perished; an officer from the doomed USS Arizona says that he survived only because he was ashore with his family; a Navy wife describes how she tended the wounded in a hospital; another describes what happened when martial law was declared in Hawaii; a reporter recalls the pain he felt after the attack when asked by a son of Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, the cashiered commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet, “Do you think my father is really as guilty as everybody says he is?”

And there is much more. Five accounts tell of the dramatic run by USS Nevada, the only battleship off Ford Island to get underway during the attack; Captain Mitsuo Fuchida describes how he led the carrier-plane assault and sent the famous signal, “Tora, tora, tora!”; Admiral Robert B. Carney explains why “the Navy was not ready for war”; Captain Joseph K. Taussig, Jr., the son of an admiral and one of the heroes of December 7, provides a tactical view of Pearl Harbor’s defenses; Rear Adm. Arthur H. McCollum, then head of the Far East desk at the Office of Naval Intelligence, outlines the unheeded warnings that preceded the attack; Vice Adm. Lawson P. Ramage, later a submarine hero and Medal of Honor winner, describes his “grandstand seat” during the raid; Brig. Gen. Samuel R. Shaw tells how the Marines patrolled for spies and saboteurs after the raid; and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins recalls how a shaken but calm President Franklin D. Roosevelt formulated his response on the night of December 7.

Other contributors include Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz; correspondents Hanson W. Baldwin and Joseph C. Harsch; and Admirals Arthur W. Radford, Kemp Tolley, Thomas H. Moorer, and Edwin T. Layton.

This is a fascinating kaleidoscope of personal experiences.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments