By David H. Lippman

The imperious ringing of a field telephone broke up the meeting that General Vasili Chuikov was holding with his exhausted 62nd Army staff in their dugouts in Stalingrad. Someone grabbed it, and a voice at the other end squawked, “There will be an order coming through shortly. Stand by to receive it.”

At the other end of the line was Stalingrad Front (army group) headquarters, and everyone stared at each other, wondering what it meant. Army Commissar Kuzma Gurov struck his forehead, exclaiming, “I know what it is! It’s the order for the big offensive!”

Gurov was right. For months, the Stalingrad Front in general and the 62nd Army in particular had been waging a house-to-house battle for the wreckage of the city against Lt. Gen. Friedrich Paulus’s German 6th Army. Both sides were bleeding out their men and strength.

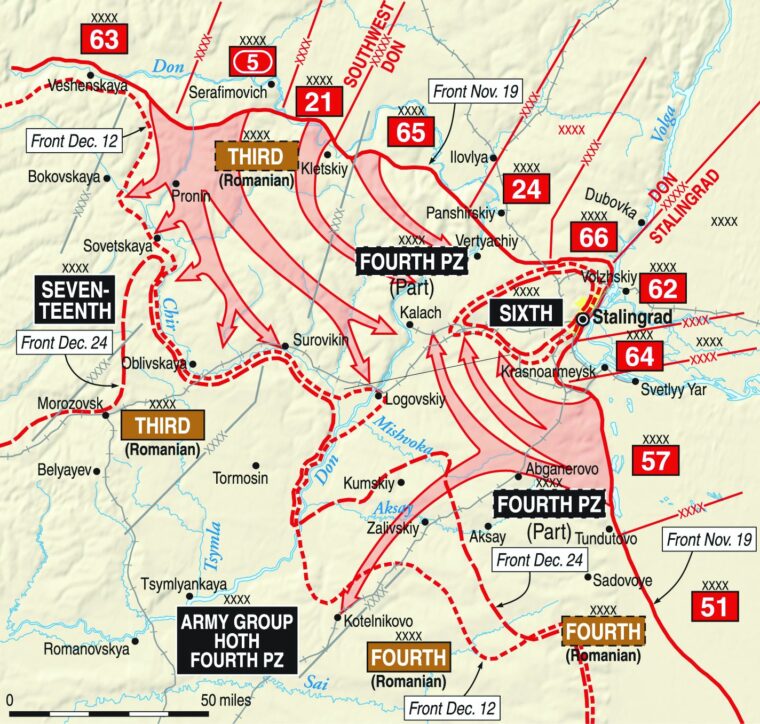

Now the Soviets were ready to launch their massive counterattack, under General Georgy Zhukov, their nation’s finest soldier. The counterblow was to be a blitzkrieg straight out of the German textbook: a massive Cannae-style double encirclement that would trap the 6th Army in a pocket. Soviet troops of the Southwest Front under General Nikolas Vatutin and the Don Front under General Konstantin Rokossovsky would power the northern pincer, while General Andrei Yeremenko’s Stalingrad Front would handle the southern assault.

The 6th Army’s flanks consisted of the 3rd Romanian Army on its left and the 4th Romanian Army on the right—which spoke to the heavy demands Hitler placed on his allies to take places in the line. Romanian troops fought bravely but were poorly equipped.

The German-Romanian defenders consisted of a million men all told, 10,290 guns, 675 tanks, and 1,216 aircraft. The Soviets massed a like number of men, 13,541 guns, 894 tanks, and 1,115 aircraft. Zhukov actually had fewer tanks at his command than the British 8th Army at the recent battle of El Alamein.

However, despite the even numbers, Zhukov had the advantages of position, mobility, and most of all, surprise. Soviet troops were not told of their assignments until moments before their attacks. General Reinhard Gehlen, chief of German intelligence for the Eastern Front, told his masters that the Soviets would attack Army Group Center. He was right. They did. The attack was defeated, but it was a subsidiary assault.

Following the order: “Send a messenger to pick up the fur gloves,” the big show at Stalingrad opened on November 19 at 7:20 a.m. Moscow time (5:20 a.m. Berlin time). Trumpets ordered a 10-minute artillery barrage through freezing white mist. After an hour of shelling, Soviet infantrymen advanced, while their artillery fired at enemy positions behind the lines on the German left flank.

The Romanians tried to fight back, but it was hopeless. Behind the Soviet infantry thundered hordes of T-34 tanks and cavalrymen. As the fog dispersed, Soviet aircraft were able to take to the skies while fog socked in Luftwaffe bases.

The first part of the double-barreled catastrophe fell on Paulus at 9:45 a.m. A traditional officer with a fetish for personal neatness and a stickler for good staff work, he was having a hard time leading the assault on Stalingrad. He had never commanded even a division before he took over 6th Army. Worse, the filthy conditions of the front affected his morale and he was not a charismatic figure. His Romanian countess wife complained to him bitterly about Hitler’s treatment of the Jews.

By nightfall Soviet tanks had ripped open a gap 50 miles wide, killing and capturing thousands of Romanians. In Moscow, Stalin messaged his generals to attack harder, but made a public speech referring to the upcoming October Revolution ceremonies, saying, “There’ll be a holiday in our street, too.”

The Soviets launched the second barrel of the offensive the following day, with Yeremenko’s forces—most weary from defending Stalingrad—attacking at 10 a.m., two hours late. Soon the Soviets bagged more than 10,000 Romanians and cut open a 30-mile hole.

The two mighty Soviet pincers were headed for the major German bridge at Kalach that supplied the entire 6th Army, which saw German truck, horse, and camel convoys crossing it, driving through snow and frost, Russia’s traditional weather allies. The Soviets moved with such speed that Paulus either could not, or was simply unable, to react. The logical riposte was a counterattack by the 48th Panzer Corps in reserve, but mice had eaten through the tanks’ wiring, and the unit had difficulty moving up.

Worse, the Soviet attack was taking place outside 6th Army’s area of responsibility, so it was incumbent on General Freiherr Maximilian von Weichs, boss of Army Group South, to address the situation. He and Paulus awaited orders from Adolf Hitler at Berchtesgaden.

While the Germans tried to figure out what was happening, the Soviets advanced. On November 21, the overmatched 20th Romanian Division’s soldiers perished in battle while their officers and NCOs drank. On November 22, Soviet ambulances dropped their loads to bring up ammunition.

The 6th Army was facing a catastrophic situation—its divisions had been using up fuel, food, and ammunition almost as quickly as it could be brought up, and there was little reserve. If the Kalach bridge fell, the army would be cut off.

Now the two massive Soviet forces piled in on the bridge and its thin defenses—some supply troops, MPs, 16th Panzer Division’s workshops, and a flak battery. Lt. Col. G.N. Filippov’s 19th Tank Brigade charged forward with two captured German tanks in the lead to fool the enemy. At 6:15 a.m. on the 22nd, the tanks attacked, driving off the German detachment, preventing them from blowing the bridge across the Don River.

Soviet troops from the two encircling forces fired recognition flares that guided each other toward their positions, and everybody met with bear-hug embraces and exchanges of vodka and sausages. Unfortunately, they beat the Sovfoto news cameras to the link-up, so it had to be recreated again for the newsreels later.

Paulus and his men were stunned. November 22 was “Totensonntag,” the “Sunday of the Dead,” the solemn Great War remembrance, and now it was harder than ever. An entire German army was in peril. As Captain Baron von Freytag-Loringhoven recalled later, “We became very much aware of what danger we were in, to be cut off so deep into Russia on the edge of Asia.”

Paulus undertook the only immediate measure he could, withdrawing 6th Army into a pocket based on his airfields near Stalingrad, to maintain cohesion. The most important of them was Pitomnik, which had a proper runway and lighting. In a typical Russian hard-snow winter, the withdrawal was difficult for an army that relied on horse transport and half-starved Soviet POWs as beasts of burden. On top of that, despite the horrors of the Moscow battle, neither the Germans nor the Romanians had been issued winter uniforms.

Paulus signaled Berlin at 6 p.m. on November 22: “Fuel supplies almost exhausted. Tanks and heavy weapons will be immobilized, ammunition situation acute, food supplies available for a further six days.”

Weichs recommended that 6th Army break out of the new pocket, even though it might suffer heavy casualties. Col. Gen. Kurt Zeitzler, Chief of the General Staff, said, “It is a crime to leave 6th Army where it is. The entire army must inevitably be slaughtered and starved. We cannot fetch them out. The whole backbone of the Eastern Front will be broken if 6th Army is left to perish at Stalingrad.”

Hitler’s answer was to say 6th Army was “temporarily surrounded by Russian forces. It is my intention to concentrate 6th Army…(it) must be left in no doubt that I shall do everything to ensure that it receives its supplies and that it will be relieved in due course. I know the brave 6th Army and its Commander-in-Chief, and I also know that it will do its duty.” Despite these calm-sounding words, Hitler’s reaction seems to have been one of furious anger.

Paulus responded on the 24th, saying that 6th Army “could only hold fast with the necessities of life, fuel, ammunition, and food, and other clearly specified materiel, and if it can be assured of relief from outside the encirclement within a short period of time.”

The first move was to hurl the 48th Panzer Corps against the encircling Soviets, which consisted of two German panzer divisions and one Romanian. When the mechanics swapped out the wiring, the tanks clanked ahead and became trapped in the snow. A furious Hitler threw the corps commander, General Ferdinand Heim, in prison.

Hitler further replaced Weichs with one of the war’s greatest generals, Erich von Manstein, giving him command of the new Army Group Don and orders to break through to relieve Stalingrad. While Manstein assembled his forces and made his plans, 6th Army had to be armed, fueled, and fed. Hitler turned to Reich Marshal Hermann Goering, head of the Luftwaffe, and ordered him to supply what was officially designated “Fortress Stalingrad” and “Der Kessel”—The Cauldron—by the freezing 6th Army troops.

“Mein Fuhrer,” Goering said grandly, “I announce that the Luftwaffe will supply the 6th Army by air.”

Zeitzler found that preposterous. “The Luftwaffe just can’t do it,” he retorted. “Are you aware of how many daily sorties the army in Stalingrad will need?”

“Not personally,” Goering replied. “But my staff knows.”

“The 6th Army needs 500 tons a day,” Zeitzler said.

“I can manage that,” Goering said.

“It’s a lie!” snapped Zeitzler.

Hitler intervened: “The Reich Marshal has made his announcement, and I am obliged to believe him.”

Actually, 6th Army requested a delivery of 750 tons of supplies every day. The Luftwaffe transport officers told Goering that they could only deliver 350 tons per day, and only for a very short period. There were only about 180 Ju-52 transport planes on hand to do the job.

Goering had to scrape up the reliable but vulnerable “Tante Jus—or “Aunt Ju”—from nearly every command in the Reich, including those that were ferrying men and munitions from Sicily to Tunisia to stop the advancing British and American armies there. Goering also committed Ju-86 trainers, four-engined FW-200 long-range reconnaissance planes (cargo capacity: six tons) and 100 He-111 bombers to the mix as well. There was some sense in using those three types: all were converted civilian airliners. Now they would be used in their old jobs. None had the cargo capacity of the American C-47 transport plane, and the Luftwaffe had none of the experience the Americans and British had of long-distance air transport.

Even so, when told that Hitler would send clouds of transport planes and Manstein with hordes of tanks to free them, the average 6th Army German “landser”—their word for “Tommy”—believed Der Fuhrer. When one landser told a buddy that they were doomed, his buddy retorted, “You’re a real pessimist. I believe in Hitler. What he’s said he’ll do, he’ll stick to.”

As November ended, Paulus regrouped his forces, using up most of his fuel and ammunition, to ensure that Soviet forces could not attack his rear. All offensive moves in Stalingrad were stopped. The 14th and 16th Panzer Divisions and the legendary Austrian 44th Hoch und Deutschmeister Infantry Division moved to the west side of the Kessel.

Paulus began taking desperate measures. The lack of fodder meant that all horses had to be slaughtered to feed the men, who were on between one-third and one-half rations. When Zeitzler heard of this, he put himself on “Stalingrad Rations” in a gesture of solidarity with the landsers, losing 26 pounds in two weeks. When Hitler was told of that, Der Fuhrer ordered Zeitzler to resume a normal diet. However, Hitler banned champagne and brandy at Fuehrer Headquarters “in honor of the heroes of Stalingrad.”

About 290,000 men were trapped in Stalingrad, including two Romanian divisions and the 369th Croatian Infantry Regiment. The besieged Landsers started digging trenches in the mud. The intense cold turned their coal scuttle helmets into freezers—men replaced them with fur caps wherever possible. Dysentery and influenza spread. Troops, even the fastidious Paulus, who Hitler promoted to colonel general in recognition of his stand, were covered with lice.

The center of German air-supply efforts in Stalingrad was Pitomnik Airfield. Soviet artillery could train their guns on the airfield, and harsh winter weather could shut it down easily—there were many days of zero visibility. One snowstorm followed another. Temperatures were so low it was almost impossible to start engines without lighting fires beneath the tri-motored Ju-52 transports.

When “Die Luftbrücke”—the “Air Bridge” —started, it was an immediate failure. A hundred Ju-52s were promised per day in the first week, but the average was 30 flights per day. Soviet fighters and flak shot down 22 transport planes on November 24 alone. Nine more were lost on the 25th. He-111s were taken off bombing missions to make up for the losses. The 350 tons included only 14 tons of food. Luftwaffe General Wolfram von Richtofen, a cousin of the Great War Red Baron, head of the German Fliegerkorps 8, the main German air force unit in the Stalingrad area, told Berlin that he could not supply Stalingrad. Goering ignored him. The Luftwaffe kept trying, delivering 512 tons on the week of December 6, but it was not nearly enough.

The Luftbrücke organization soon proved chaotic. One day’s lift brought in four tons of marjoram and pepper. An angry supply officer asked if his men were supposed to hurl the pepper in the Russian troops’ faces. Another day flew in millions of contraceptives. By December 9, the Luftbrücke was only bringing in about 84.4 tons per day, and Landsers were starting to die of starvation in the Kessel.

The failure seemed academic, as the big plan was not relief by air, but committing Manstein and his panzers to the massive counterattack. Everybody knew it was coming, most of all the Soviets, who developed Operation Saturn, which would use two Fronts to attack the Italian 8th Army to the north of Manstein and leave his anticipated counterattack out on a limb. Meanwhile, Soviet forces would stop Manstein cold on the Myshkova River.

Manstein got down to business on December 12, launching Operation “Wintergewitter”—“Winter Storm”—with three panzer divisions, 17th, 6th, and 23rd, driving north from Kotelnikovo across the frozen steppes to Myshkova, protected on their right by the 4th Romanian Army and on their left by Army Detachment Hollidt and north of that, the Italian 8th Army. General Hermann “Papa” Hoth, leading the 4th Panzer Army, would command the assault. The 6th Panzer Division had a difficult trip to the Eastern Front from its base in France—it endured constant partisan harassment, blown bridges, and torn-up tracks all through its trip through Russia to the front.

While Hitler insisted that “6th Army will still be in position at Easter,” the canny Manstein knew Paulus’s freezing and starving men could not hold. He drew up “Operation Thunderclap,” which would see 6th Army execute a breakout from the Kessel and link up with his forces.

Winter Storm drove to the Myshkova River with the usual Teutonic tenacity. In the Kessel, Landsers defending the pocket’s southwest corner could see gun flashes by night and hear, when the wind was right, the rumble of Hoth’s artillery. They told each other, “Der Manstein Kommt!”—“Manstein is coming!”—which boosted morale.

Yeremenko, who had defended Stalingrad all through the bloody battle there, now faced Hoth on the Myshkova River. He deployed his T-34s to face the German assault, which included something new—a battalion of Mark V Panther tanks, and another of Mark VI Tiger tanks, which packed 88mm guns. The 6th Panzer Division got into a three-day battle described as “a gigantic wrestling match,” amid mud and rain.

While the struggle raged, Manstein sent intelligence officer Major Eismann, into the Kessel to brief Paulus on Thunderclap. What was said remains controversial, but apparently nobody gave Paulus a direct order to commit to Thunderclap and launch the breakout. In addition, Paulus and his staff worried that their increasingly exhausted troops would be unable to physically meet the stress of attacking their way out of the Kessel. Manstein fretted over their condition, too, and passed the buck up to Hitler, who ordered 6th Army to stay in place, holding “Stalin’s City.”

While Hoth’s tanks struggled to cross the Myshkova, the Soviets revved up what was now called “Little Saturn,” their attack on Hoth’s distant left flank. On December 16, the Voronezh Front slammed into the 200,000-man Italian 8th Army, a force that included some of the best units in that nation’s order of battle, like the Savoia Cavalry Regiment and the 3rd “Julia” Alpine Division.

The Italians fought hard, but Soviet numerical, technological, and leadership advantages told the tale—soon the Soviets had surrounded the bulk of the 8th Army. Only 25,000 Italians and 7,000 Germans were able to retreat. The rest of the 8th Army lay in a separate pocket, which was also crushed. The Italians lost between 65,000 and 70,000 dead and 50,000 men fell into Soviet captivity. The Soviet forces wheeled south after the victory to tear into the left flank of “Winter Storm.”

Now Manstein faced an agonizing situation. He could no longer maintain the relief drive on Stalingrad, as his left was outflanked —Army Group Don itself was in danger of annihilation. On December 23, Manstein ordered Hoth to cancel “Winter Storm” and withdraw his troops to halt the Soviet drive. A German tank officer stood in his turret and saluted to the north—a final farewell to the 6th Army. In the Kessel, unhappy Landsers watched the gun flashes fade and heard them replaced by silence.

The Stalingrad temperature fell to -25 degrees on Christmas Day with snow flurries. That day saw 1,280 men die in the Kessel, most from wounds, frostbite, typhus, dysentery, and starvation. Paulus gave his men a holiday gift: six ounces of bread, three of meat paste, one of butter, and one of coffee. He did not tell them that the following week their rations would be cut to two ounces of bread, one bowl of soup without fat for lunch, and if it was available, one can of meat for dinner. The 3,500 Soviet POWs still held by 6th Army fared worse. They ate rotting corn. It occurred to nobody to simply release them.

Both sides used propaganda, the Germans to keep up their own morale, the Soviets to wreck it. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels made broadcasts hailing the courage of the 6th Army, playing their fight song, “Das Volga Lied”—the “Volga Song”—on the radio. The Soviets used loudspeakers and German Communists, including Walther Ulbricht, to promise surrendering Landsers good treatment and hot food. The Germans initially treated these broadcasts to mortar fire, but stopped when ammunition ran short.

The most powerful Soviet propaganda broadcast was a ticking metronome. It was interrupted by a recorded voice that said, “Every seven seconds, a German soldier dies in Russia. Stalingrad is a mass grave.” Then the metronome would tick for another seven seconds.

The Soviets delivered artillery barrages and aggressive patrols against the 6th Army, as their own supplies were also short—most of them were going to the battles with Manstein and Army Group Don. However, once Manstein began his withdrawal, it was time to strangle 6th Army.

The job was given to the Don Front under Voronov, who would attack Paulus from the west, over open ground, rather than Yeremenko’s men from the east. Operation Ring was presented to Stalin and Zhukov in Moscow on December 27th, and Zhukov immediately objected to Yeremenko’s exclusion from the final victory. His men had held Stalingrad for months in bitter fighting against tough opposition.

“Yeremenko will be very hurt,” Zhukov said.

“We are not high school girls,” Stalin retorted. “We are Bolsheviks and we must put worthwhile leaders in command.” Zhukov broke the news to Yeremenko.

The field attack leader would be one of Russia’s best generals, Rokossovsky, and he would have 47 divisions mustering 218,000 men, 3,610 field guns and mortars, 169 tanks, and 300 aircraft to finish off 6th Army. The attack date was set for January 10, 1943.

Meanwhile, both sides at Stalingrad marked the new year. The Soviets did so two hours ahead of the Germans, who stuck to Berlin time wherever they went. At midnight Moscow time, the Soviets delivered a massive barrage and fireworks display. Two hours later, the Germans only fired a few star shells. They could not waste ammunition.

Despite their desperate plight, the Germans tried to celebrate. Paulus wrote his wife, “Our will for victory is unbroken and the New Year will certainly bring our release! When this will be, I cannot yet say. The Fuhrer has, however, never gone back on his word, and this time will be no different.” He took time to present General Edler von Daniels, who commanded the 376th Infantry Division, with a bottle of Veuve-Clicquot to honor his promotion to lieutenant general. Von Daniels was one of many generals whom Hitler showered with promotions to encourage them to resist.

Ordinary Landsers wrote home confidently, too. “Dear parents, I’m all right,” wrote one. “Unfortunately I have to go on sentry tonight. I hope that in this New Year of 1943, I won’t have to survive as many disappointments as in 1942.”

Hitler sent his greetings to Paulus, too: “The heroic stand of your troops has my highest respect. You and your soldiers, however, should enter the New Year with the unshakeable confidence that I and the whole German Wehrmacht will do everything in our power to relieve the defenders of Stalingrad and that with your staunchness will come the most glorious feat in the history of German arms.”

The message went over well. A captain wrote, “We’re not letting our spirits sink, instead we believe in the word of the Fuhrer.”

Even so, it was clear the Soviets would attack soon, and Paulus had only 150,000 starving, frozen, and exhausted troops to face Rokossovsky’s onslaught. Men lacked boots, trousers, and socks. Only one in five defenders were actual frontline soldiers. The rest were rear area paper chasers going through hurried combat training on the windy steppes. With divisions and regiments battered, they were amalgamated into ad hoc battle groups. Fortunately, doing so was a German specialty. Sgt. Maj. Wallrawe’s company included redundant Luftwaffe ground personnel and renegade Don Cossacks.

The Soviets had their own problems. Despite warm clothing and hot food, the harsh weather impacted them, too. They also lacked coordination. Voronov went to the front to take a look for himself and was annoyed to see a group of Ju-52s sedately parade 9,000 feet overhead, without anyone shooting back. Soviet fighters arrived too late to catch them, and antiaircraft guns didn’t open fire. Voronov terrorized airmen and AA gunners into greater efforts.

Meanwhile, the Luftbrücke struggled on. December 19 was its best day, when 154 aircraft landed with 289 tons. Yet the Pitomnik airfield was soon littered with the wrecks of crashed transports. Soviet bombers—including a squadron of women—pasted Pitomnik by day and night. The combination of cold, horrific sights of starving, wounded men, piles of frozen corpses, and the desperation of the airlift wore down the increasingly exhausted airmen.

The planes hauled out wounded men, but there were often violations, men with self-inflicted wounds or bandages over undamaged arms. Officers who had written their own orders to fly out of the Kessel “for special duties” challenged the MPs, known as “chain dogs” for the gorgets they wore.

The top brass in Berlin had their own worries. Hitler had ordered that senior Nazi vassals could not use their power to get anyone out of the Kessel. Armaments Minister Albert Speer’s youngest brother, Kurt, was hospitalized in Stalingrad with a variety of ailments and the best Speer could do was promise him a transfer to France once 6th Army was relieved. Kurt Speer died in the fighting anyway.

When word got around the 6th Army that Winter Storm had failed and they were on their own, morale and temperatures plummeted. Amid -35 degrees temperatures, half-starved ponies hauled rations on sleds to waxen-faced, unshaven, filthy troops. Bread was down to 200 grams a day and often 100 grams. Landsers tried to cut up dead horses, but they were frozen so stiffly it took a pioneer saw to do it. Rumors ran rampant. The 4th Army had reached within a dozen miles of the Kessel but was ordered to stop there.

As January wore on, Landsers began to surrender. The Soviets added incentive by cooking large quantities of tasty food in their frontline trenches and letting the aroma drench German nostrils.

German wounded endured a special nightmare as ambulances were rare—they were targets for shelling—and medicine shortages meant that very few could be properly cared for. All too often a wounded man would be loaded for evacuation on a transport only to see the plane shot down or crash shortly after takeoff, killing all aboard.

Paulus decided a “Frontkämpfer”—“battle warrior”—from his staff might convince Hitler to take strong action, and he sent Captain Winrich “Teddy” Behr out by air. He survived the two-hour flight to Manstein’s HQ at Taganrog, where he reported to the field marshal on 6th Army’s plight in graphic terms. Manstein responded directly: “Give Hitler exactly the same description you gave me.”

Behr flew to Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg in East Prussia, where Der Fuhrer was brooding over his essential maps along with 20 officers.

After proper greetings, Hitler responded by saying, “When you speak with General Paulus, tell him this and that all my heart and hopes are with him and his army.”

Behr then gave his report, whose frankness —including accounts of German desertions—annoyed Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel to the point that he shook his fist at Behr. The captain continued anyway, rattling off the miserable Luftwaffe delivery statistics. Were they accurate numbers, Hitler asked.

A Luftwaffe general responded: “Mein Fuhrer, I have here the list of planes and cargoes dispatched per day.”

Behr snapped, “For the Army, what is important is not how many planes were sent out, but what we actually receive. We are not criticizing the Luftwaffe. Their pilots really are heroes, but we have received only the figures I have told you. Perhaps some companies retrieved odd canisters and kept them, without notifying their headquarters, but not enough to make a difference.”

Hitler’s response was to offer sympathetic remarks and promise a new relief effort to be mounted by an SS panzer army being massed at Kharkov. Unfortunately for all concerned, Manstein had told Behr already that the SS army would require several more weeks before it could attack. “It was the end of my illusions about Hitler,” Behr said later. “I was convinced he would lose the war.”

Instead of hurling SS panzer troops against Soviet troops, Hitler sent Luftwaffe Field Marshal Erhard Milch, one of Goering’s cronies, to take over command of the airlift. The field marshal headed for the front to restore order, and Hitler placed all Luftwaffe assets supplying Stalingrad under “Fliegerfuehrer Milch.”

Hitler also showered more decorations on Stalingrad, awarding Paulus the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross and 178 medals to other senior 6th Army officers.

However, Manstein had given up all hope of relieving 6th Army. Its only purpose now was to draw off Soviet forces to enable him to withdraw even larger bodies of German troops from the Caucasus before they, too, were trapped.

Landsers in the Kessel knew they were doomed, too, and their last letters home, posted on January 15, 1943, reflected their fear and despair. “Fate has decided against us,” wrote a corporal to his parents. “If you don’t receive the news that I have fallen for Greater Germany, then bear it bravely. As a last bequest, I leave my wife and children to your love.”

In the first week of January, the Kessel’s frontline was quiet. Paulus reduced the bread ration to 75 grams. On January 10, the Soviets began “Operation Koltso”—“Ring”—to crush the 6th Army. Seven thousand Katyusha rocket launchers, field pieces, and mortars blazed away at the Germans. Artillery commander Colonel Ignatov remarked, “There are only two ways to escape from an onslaught of this character—either death or insanity.”

The assault went in on the western side of the Kessel against what was left of the 44th Infantry, 3rd and 29th Motorized Division, and von Daniels’ 376th Infantry, who said the attack created a “most unpeaceful Sunday.”

Landsers could barely fire their weapons—their fingers were frozen from frostbite. T-34 tanks carrying infantry clattered across the snow, blasting apart the defenses. Sgt. Maj. Wallrawe’s scratch force of rear area men held on until 10 p.m. on the first night and then pulled back. From there on, Wallrawe wrote, his troops never enjoyed warm food or a safe bunker.

Paulus committed his few working tanks to a counterattack, but they were defeated by every weapon and man the Soviets could muster, from T-34s to Il-2 Sturmovik dive bombers, to mortar fire. The 82nd Romanian Regiment abandoned its positions. By the end of January 11, the Soviets counted 1,600 fresh German corpses, lying in grotesque positions, and acres of abandoned and wrecked vehicles and equipment.

Paulus signaled Berlin: “Munitions coming to an end.” His men were barely able to dig trenches, so the emaciated Russian POWs did so. Incredibly, Pitomnik continued to operate, with Ju-52s flying meager supplies in and wounded men—Wallrawe among them—out.

Despite Milch’s best efforts, the Luftbrücke was a total failure. The last Me-109 fighters flew out of the Kessel on Richthofen’s orders. The transports followed. On January 16, the Germans abandoned Pitomnik. Soviet troops advancing on the airfield were puzzled to see huge shapes in the middle of the steppe—they were wrecked German aircraft.

Now the Landsers knew they were doomed. Soldiers asked superiors for poison. The hospital at the Gumrak airfield was filled with dying men, covered with lice. As soon as a Landser expired, the lice migrated to the man on the next cot. Many German soldiers lay apathetically in basements, awaiting any kind of end.

Milch kept trying, now ordering his planes to parachute supplies, including a Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves for Paulus. The general begged permission to break up his army and let the men flee across the steppe, every man for himself. Hitler vetoed that. Instead, Paulus flew out officers who would make up the nucleus of a new 6th Army. Among those was Freytag-Loringhoven, who described the horrors of Stalingrad to Manstein. Then, still in his lice-covered uniform, he collapsed on a warm bed in the staff train.

The final Soviet offensive faced only spasmodic defenses. Paulus’s men were out of everything, including spirit. Paulus begged Hitler for permission to surrender. Hitler retorted: “Surrender is forbidden. The 6th Army will hold their positions to the last man and the last round and by their heroic endurance will make an unforgettable contribution towards the establishment of a defensive front and the salvation of the Western world.” It was a sordid lie.

It didn’t matter. On January 30, Hitler promoted Paulus to field marshal, the implication being that no field marshal in German history had ever surrendered—Paulus was expected to commit suicide.

That didn’t happen. The Soviets overwhelmed exhausted, starving, freezing German troops in the ruins of Stalingrad and their bunkers. None were eager to fight on. Among those wounded was Paulus himself. Filthy and freezing, he and his staff emerged from his Univermag department store basement headquarters to surrender to Voronov. Sovfoto cameras captured the emaciated, unshaven field marshal and his top brass as they yielded 91,000 men, including 2,500 officers and 24 generals. More than 125,000 Germans lay dead. Soviet deaths numbered 485,751 for the entire campaign, but the Germans and their allies lost well over a million men in that same period.

Thousands of the German POWs died in captivity. Paulus himself joined the Soviet-backed German Officers’ Bund, headed by future East German leader Walther Ulbricht, recruiting POWs to join the Soviet cause. After the war, he testified for the prosecution at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, infuriating the defendants. Paulus died in East Germany, never seeing his wife again.

That was all in the future on February 1, 1943. At his headquarters, Hitler raged over Paulus’s failure to shoot himself. The last 6th Army message came that day at 5:45 a.m: “The Russians stand at the door of our bunker. We are destroying our equipment. This station will no longer transmit.”

David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He resides in New Jersey.

Join The Conversation

Comments