By Jon Latimer

Boarding a train at the famous station built by the French as a terminus on the line from Djibouti, the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, Elect of God, Ras Tafari, Emperor Haile Selassie of Abyssinia left his capital Addis Ababa on May 2, 1936. He had been forced to abdicate by the indifference of the world to his plight and the impotence of the League of Nations to stop the march of fascism.

The emperor addressed the League on June 30, describing the suffering of his people at the hands of the Italians who had been prepared to use mustard gas to defeat his own hopelessly medieval forces. “It is us today. It will be you tomorrow.” The Italians themselves cared only that they should avenge the terrible stain of Adowa, the field where they had so ignominiously failed in Abyssinia 40 years before. But at the same time, Jan Smuts, one of the great leaders of the Boers in their struggle for freedom from the British at the beginning of the 20th century asked, “Shall we fight evil with its own weapons? Can we allow force to submerge everything without mustering greater force to stop it?”

Mussolini’s Ill-Conceived African Empire

This was the dilemma facing the people of the Union of South Africa when war came. Indeed, it was a close call in Parliament before South Africa joined the rest of the British Empire in going to war with Germany in September 1939. At this stage, however, war with Italy was but a distant prospect. Mussolini’s declaration of war against the British Empire on June 10, 1940, was a typical piece of opportunism, designed to benefit from the successful German campaign in Western Europe while casting a covetous eye on British possessions. For this greed, Mussolini would pay a heavy price in North and East Africa.

Despite the warnings of his senior officers, Mussolini was glibly unaware of the realities of modern warfare and of Italy’s unpreparedness for it. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Italian East Africa. The strategic position of its colonies in Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia (Abyssinia) was weak. Sea communications could be strangled easily; the British protectorates of Egypt and Sudan sat astride the air routes so that the nearest Italian post and landing ground lay over 1,000 miles away at Uweinat in Libya. If these links were cut, there was little enough that could be provided locally, and Ethiopia was a military liability during the best of times.

The situation presented an internal security nightmare to Viceroy Amadeo di Savoia, the Duke of Aosta, and despite the 250,000 troops present, these were organized and equipped only with security duties in mind. After pleading with Rome for reinforcements as war became increasingly likely, all that had arrived by the outset was a company of medium tanks, 48 field guns, and assorted specialists. Of the logistic backup needed for mobile warfare, Aosta had none, and his vehicles and aircraft were short of fuel, spare parts, and, above all, tires.

The Great North Road

The South Africans were as unprepared as everyone else when war came, but one of the first actions taken was the requisition for war production of the Ford and Chevrolet plants located in the country. A survey was made of the “Great North Road” between Pretoria and Nairobi in Kenya. The commander in chief of British forces in the Middle East, General Sir Archibald Wavell, took a keen interest in the progress of the Union’s defense forces. By May 1, 1940, some 20,000 South Africans were in Nairobi together with three South African Air Force (SAAF) squadrons, and the 1st South African Brigade was soon to disembark at Mombasa. For the British, this contribution was enormously significant; the South Africans were fully motorized, and previously only 8,500 troops had been on station to guard a frontier with the Italians that was over 1,000 miles long.

British forces in Sudan were equally sparse, and during July the Italians had little difficulty occupying Kassala and Gallabat in eastern Sudan. They remained nervous, however, and a mere company of British troops nearby was inflated on Italian staff maps to a unit of 20,000 men! The British took advantage of this until, in August, Wavell sent the 5th Indian Division to Port Sudan.

To the northeast of the Italians lay British Somaliland. Wavell was instructed not to augment the garrison there, but he eventually resolved to make a total of five battalions available for its defense, adding the 2nd Battalion of his old regiment, the Black Watch. The Italians duly crossed the frontier on August 3 heading for Berbera, the capital and main port. Greatly outnumbering the defenders, they inevitably forced them back after a stout resistance based on a line of hills at Tug Argan and entered Berbera after losing 2,052 casualties and failing to interfere with an evacuation on the 19th.

By now, a steady stream of vehicles was making its way along the Great North Road. By the end of the year, some 9,000 mainly one- and three-ton trucks driven by inexperienced Africans had made the trek across desert and bush, which would make a major contribution to the British move on Addis Ababa. There would be 29 transport companies for the South Africans and 25 to support the East African forces now assembling. As these operations were unfolding, the air campaign commenced with the SAAF beginning a series of raids from Kenya against their opposite numbers at Yavello and Naghelli. Wavell also took steps to encourage a revolt of patriots to prepare the way for a return of Selassie. All these measures would take time, and before any attempt to wrest Ethiopia from the Italians could be attempted, months of hard work would be necessary.

The Logistics of Invasion

The invasion of Ethiopia from Kenya was to be a feat of military engineering that possibly ranks alone in history. Smuts called on the resources of the various government departments in Pretoria: roads, forestry, irrigation, survey, and railroads. They were staffed by men who knew Africa and knew about the lack of expertise and trained manpower in Kenya. They also knew the difficulties that would face a modern force with all its ancillary support services across waterless, trackless desert and bush. Smuts brought in Colonel A.J. Orenstein, who had been director of medical services during the East African campaign of 1916-1918 when the men of the Union and Empire had been decimated by the equatorial illnesses prevalent there. This time, both men were determined that these services would be the most efficient the times could supply, and here the engineers’ provision of the means to go forward fully motorized would both spare the soldiers from the worst privations and enable casualties to be quickly evacuated.

From the gold mines came geodetic and map-making personnel who would produce 1:25,000 maps from aerial photography. Previously, the only maps available had been 1:1,000,000 scale. As the process of assembling the supply infrastructure took place, the Geological Survey Section was operating in the Northern Frontier District, searching for the water supplies that would be needed once the troops were on the ground. Much was needed immediately; the engineers were engaged in building roads through such areas as the 21-mile stretch of lava escarpment from Maikona to Kalacha in the Chalbi Desert. This tremendous effort was in preparation for a move that the Italians were convinced was impossible.

By October, the 1st South African Brigade had been joined by the 2nd and 5th South African Brigades, and the engineering tasks were steadily continuing. The SAAF in their Pretoria-built Hartebeest aircraft made systematic attacks on enemy camps, fuel dumps, and transport assets. Week after week, these operations continued, with the air crewmen risking an appalling fate if shot down in open bush.

Raid on Dingaan’s Day

With the Italian invasion of Egypt in full swing, Wavell’s attention was concentrated northward. He was still convinced that the best way of eliminating the threat posed in Ethiopia was through an armed uprising of patriots. The eventual campaign in Ethiopia would be the result of evolution rather than a comprehensive plan. Smuts argued that plans made for regaining Kassala and Gallabat should be accompanied by a plan for an attack up the Somali coast to remove the threat to Mombasa posed by Italian forces at Kismayu. This was regarded as impractical by both British and Italian experts. Neither, however, seemed to possess the Boer genius for mobility. Everything depended on the rains. These would reduce roads to impassable mud and were expected around March. Lt. Gen. Alan Cunningham, appointed to command in Kenya in November, advised against moving before May.

Before that, raids were to be conducted in preparation. The first was to be made by the 12th African Division under Maj. Gen. Alfred Godwin-Austen with the 1st South African Brigade, the 24th Gold Coast Brigade, and the 1st South African Light Tank Company, against El Wak, which was held by some 2,000 colonial infantry and a few light guns. El Wak was attacked on December 16, Dingaan’s Day as it was known to the South Africans, anniversary of the Battle of Blood River in 1836.

When the light tanks could not pierce the frontier wire, 2nd Lt. Christopher Ballenden of 1st Battalion, Gold Coast Regiment, rushed forward through machine-gun fire with a Bangalore torpedo to blow a gap, and the Gold Coasters followed with fixed bayonets. By 11 am, the 1st Transvaal Scottish had battered through thick bush for three miles to capture the 191st Colonial Infantry’s headquarters, and the 1st Royal Natal Carbineers went in singing a Zulu war song in the final rush across 150 yards of open ground.

Apart from the material gains of victory, El Wak demonstrated to both sides the moral ascendancy of the Allied forces and the ability of the South Africans to operate armor, motorized infantry, and air forces in unison. In mid-January, Cunningham directed the 1st South African Division, with the 2nd and 5th South African Brigades and the 25th East African Brigade, to attack El Yibo and its wells. A three-day ordeal ensued in which air force bombs and artillery accounted for the neutralized defenses but heat and lack of water prevented a follow-up attack. The divisional commander, Maj. Gen. George Brink, was most displeased. With the rains threatening to make the Chalbi Desert impassable and no sign of a patriot rising, Brink wanted to secure better communications. He advanced first on Mega, where 1,000 Italian troops surrendered without a fight, then on to Moyale, which was found abandoned. By this time, the main advance on Italian Somaliland had reached Mogadishu.

The Impractical Juba Line

The Italians had been colonial masters of Somaliland for nearly 30 years. In the south, the Juba River forms a natural defense line that Mussolini had ordered fortified into the “Juba Line” for some 360 miles of its length. The impracticality of this was obvious, and in February 1941, with the news of the destruction of the Italian Army at Beda Fomm and the beginning of the assault on his northern bastion of Keren, Aosta could only tell his commander, Maj. Gen. Carlo de Simone, “There is no hope of reinforcement.” Both men knew talk of “no withdrawal” was mere bravado and fooled nobody.

With the South African engineers once more producing Herculean efforts (170 miles of road in 17 days), the Italians abandoned Kismayu. An aerial bombardment led to the rout of the 94th Colonial Infantry, which was rapidly followed by the retreating 12th African Division, and on February 14, the 1st South African Brigade reached Gobwen, some six days ahead of schedule.

Realizing the disarray facing them, Cunningham pressed on for the Juba. The Duke of Edinburgh’s Own Rifles and the 1st Transvaal Scottish reached the river only to discover the pontoon bridge destroyed and find themselves under intense fire. The First Royal Natal Carbineers were sent north to find a way across and succeeded in making a crossing in canvas boats. Engineers then facilitated the support of the 1st Transvaal Scottish and several armored cars. Just before dawn on February 18, an attack was made by the 208th Colonial Infantry, and repulsed with heavy loss.

The South Africans resumed the advance in an attempt to outflank the Italians and encountered the 193rd Colonial Infantry. The armored cars, charging in line abreast like true cavalry, put the Italians to flight. Now a rush was on for the key road junction at Jelib. Both Cunningham and de Simone had their eyes fixed on the next encounter, and the latter decided, in effect, to abandon Somaliland and retreat into the fortress of Ethiopia.

The SAAF attacked repeatedly to add to the confusion of the Italian retreat. Aosta wrote Mussolini to complain: “The Dabat [soldiers from a province of Ethiopia] state they were employed to fight men and not airplanes. They dislike the air raids so intensely that some units refuse to fight.” The support services for the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) had largely broken down, and the South Africans dominated the skies. In two weeks, the entire province of Jubaland was captured and 20,000 Italian prisoners taken. The 23rd Nigerian Brigade and the 11th African Division (into which the 1st South African Brigade was merged) took over the lead, covering 90, 120, 80, and then 65 miles per day to reach Mogadishu, barely 17 days after the opening of the campaign. Now they pressed on across the Ogaden Desert toward Harar.

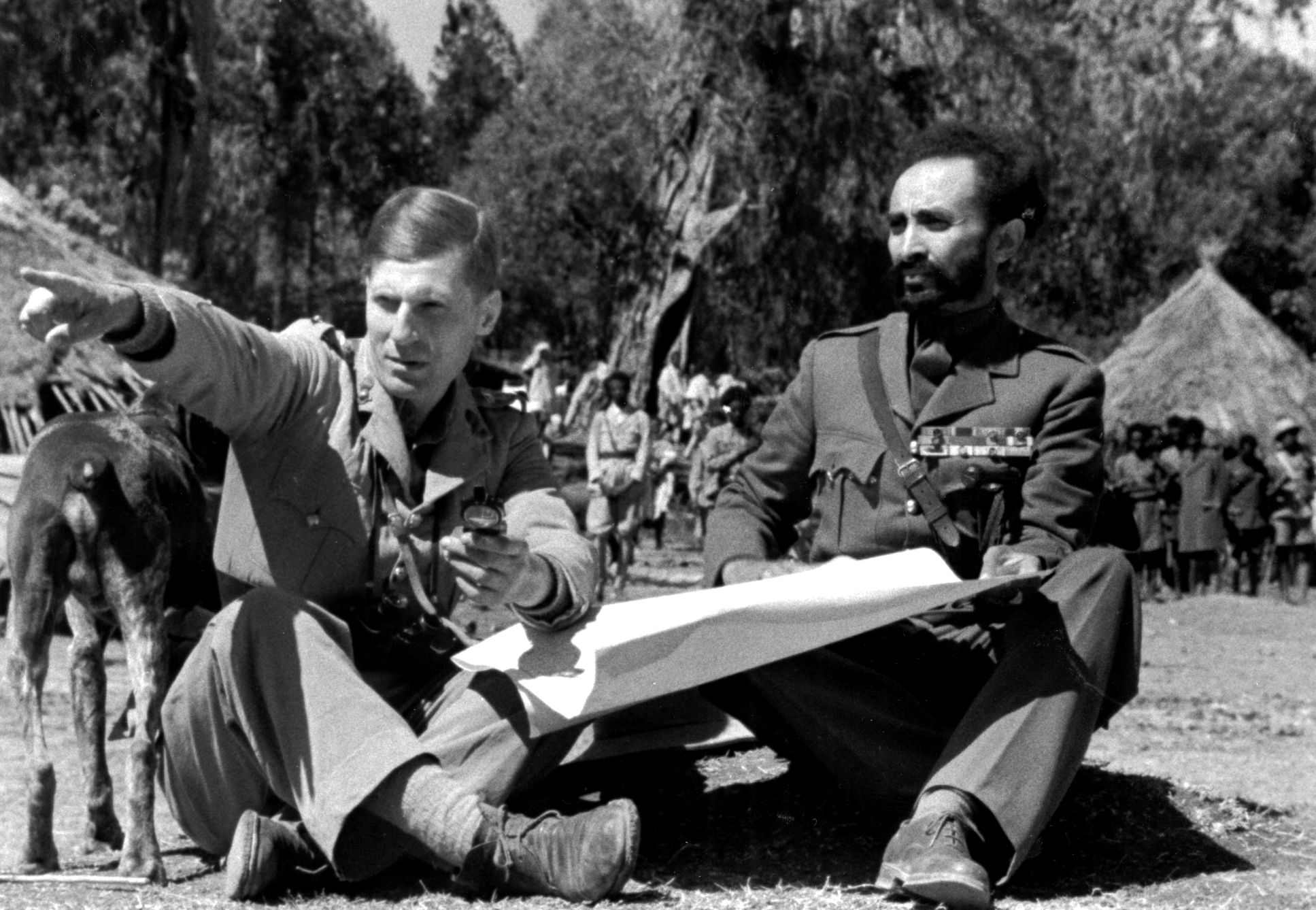

At precisely 40 minutes past noon on January 20, 1941, Haile Selassie knelt to kiss the ground of his homeland once more. He was escorted by Colonel Orde Wingate during the trek to mountainous Belaya, in an area still loyal to the emperor. When they reached the green uplands, the little emperor could not keep up despite the urgings of Wingate. “You go ahead Colonel Wingate” he said, “and let us hope the people will recognize which of us is the emperor.” Behind them trailed the miles- long caravan of arms and ammunition with which to raise the Rases (feudal lords) and their people, many of dubious loyalty. One of particular importance was Ras Hailu in Gojjam Province, a wily traitor whom nobody trusted. Treachery and disloyalty among the feudal lords were traditional and had been endemic for centuries. As Wingate prepared to take on the Italians, Hailu blocked the progress of the emperor. Meanwhile, the fortress of Keren blocked the Allies’ entry into Eritrea.

Battle of Keren

Once the Italian invasion of Egypt had been defeated at Sidi Barrani, Wavell had taken the 4th Indian Division and sent it south to join operations against Eritrea and Ethiopia. The Italians had withdrawn from the open ground of Sudan but held up the progress by the Allied forces into Eritrea at Keren.

The South African Gazelle Force, under Lt. Gen. William Platt, reached Keren on February 2. The Italians had already deployed a colonial brigade and the 11th Savoia Grenadiers with two more brigades en route under the command of General Nicoangelo Carnimeo, who was known as the Lion of Keren. Platt stuck to the Indian Army tradition, formulated after so many fights in the mountains of the Northwest Frontier: always take the high ground. The first efforts over 10 days or more had failed in the Italian view because of the Allied inability in the first hours to get around the obstructions in the pass itself. Consequently, the battle became what one historian called “a miniature Passchendaele, with heat substituting for mud.”

The key for Platt was the Dongolaas Gorge, and for 57 days the battle raged across the surrounding peaks in arid and boulder-strewn wilderness and in the face of a determined enemy. As the infantry struggled up the sheer slopes carrying the minimum equipment necessary and constantly short of water, the artillery fire was forced to lift as they approached the summit. Alert Italian defenders then manned the parapets to shower grenades among the rocks.

On February 21, Carnimeo sent a message to his men. “Your valor has thrown back the enemy … the troops have demonstrated the heroic qualities of the Italian soldier.” This was true. As the battle progressed, however, the air situation became increasingly favorable to the Allies. Platt devised a plan involving both the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions, and careful preparations were made. On the night of March 15, following large-scale air attacks and supported by heavy artillery concentrations, the attack was resumed.

Engineers finally managed an inspection of the roadblock that they had said would take two weeks to deal with and concluded that it would take two days. While this obstacle was being overcome, the Italians launched a series of fierce counterattacks against Fort Dologorodoc, a system of trenches on a bare hill surrounded by wire that had finally fallen to the Allies after changing hands numerous times. The attack along the gorge took place on March 25, and the roadblock was cleared the next afternoon. The Allies had lost 536 dead and 3,229 wounded, but the Italians lost more than 3,000 dead and 4,500 wounded. The greatest set piece battle of the campaign was over. But by no means was the campaign itself finished.

Italian Defense at the Marda Pass

De Simone was retreating across the Ogaden, with his army a disorganized rabble. What had once been a vast array of transport organized for the war of conquest six years before was now little more than a heap of junk. One prize find did appear: 350,000 gallons of gasoline. Cunningham was jubilant. It was, he said, “enough to carry the whole show into Abyssinia … the fuel problem is solved!”

The 23rd Nigerian Brigade led off on March 6 along the Via Imperiale toward Jijiga and on to Harar. At Marda Pass, where the Ethiopian mountains begin, the Italians tried desperately to organize a defensive line. Aosta thought he could still buy precious time, although he did not know that in Mogadishu the South Africans had found detailed plans describing every airfield and landing strip in the country.

This information would prove extremely useful to the Allies, whose aircraft now began a relentless attack on the Italian air transport system. Soon, motorized columns could move only at night. On March 15, a heavy attack was made on the main Italian airbase at Diredawa, destroying a number of aircraft and reinforcing Allied aerial superiority.

As British engineers struggled to repair the numerous bridges along the route of advance, everyone wondered at the lack of interference from the Regia Aeronautica. SAAF aerial photographs revealed a strong defensive position at Marda Pass. Would this prove to be another Keren? Supported by South African artillery, the 23rd Nigerian Brigade attacked, and the Italians withdrew from the pass during the night.

“I Want Every Bridge Destroyed”

The advancing Allies were now entering a land in which nothing is below 5,000 feet elevation. Three roads led from the pass to Harar, and these were taken by different formations. The Nigerians forced a position at Bisidimo, and two Italian colonial infantry regiments mutinied against their commanders. The beginning of the end was clearly in sight. Harar was surrendered on March 26, and Italian troops were rounded up by the hundreds. Intelligence estimates put total Italian losses from battle, desertion, and disease at about 50,000. Addis Ababa lay 320 miles away, a mere eight days for fully motorized forces.

Haile Selassie was also hundreds of miles from his capital, but his progress seemed less assured. Ras Hailu wanted to negotiate only with Wingate. One of Wingate’s party noted, “Only a man who from his youth played the game of patience with long-term strategies of a cool head could have shown the forbearance that Haile Selassie now displayed.”

De Simone’s plan was to hold the Awash Gorge long enough to permit Aosta to withdraw from Addis Ababa to his chosen last place of refuge, Amba Alagi. He said, “I want every bridge destroyed. At Hubeta Pass, if the engineers do a good job of demolition, they (the Allies) should be held for weeks.” But the South Africans now took the lead in the advance, and the destroyed or damaged roadways in Hubeta Pass were quickly repaired. The Johannesburg gold miners of the Transvaal Scottish repaired the roads with the inventory of a nearby brickfield.

The Allied column raced on but failed to intercept the evacuation from Diredawa. The area was full of mutinous colonial troops and a frightened white population of some 150. The arrival of armored cars restored order. A similar situation was expected in Addis Ababa, so Cunningham was granted permission by Wavell to approach Aosta, who agreed that Addis Ababa be declared an open city.

The 5th King’s African Rifles led the 22nd East African Brigade, which had covered 910 miles in 12 days, across the Awash, and so earned the honor of leading the Allied entry into the city of the King of Kings on April 5. Thus ended the southern portion of the campaign to liberate Ethiopia, following an advance of 1,700 miles in eight weeks. To the rear, mop-up operations continued, and the 2nd and 5th South African Brigades were freed for transport to Egypt. Their compatriots in the 1st South African Brigade still had work to do.

Meanwhile, in the central areas, the fall of the capital provided additional impetus to the patriot uprising and Wingate’s operations. It was apparent that Italian rule was crumbling. The Italians had withdrawn from Debra Markos, and Ras Hailu surrendered on April 4, although operations in Gojjam continued until May 19 before Italian resistance ended there. Platt now assumed control of the final operations. He was faced by three remaining centers of resistance, at Gallo-Sidamo, Gondar, and Amba Alagi, but he could deal with only one at a time.

Haile Selassie’s Return

The 1st South African Brigade was brought up from Addis Ababa on April 13 and came under shellfire at Combolcia, some six miles from the key town of Dessie. For six days, the South African gunners worked their pieces in a fierce duel while the infantry battalions eventually managed to roll up the position from the left flank. Dessie fell on April 27 after little more fighting, and another 8,000 prisoners were bagged. That same day, Haile Selassie was given permission to make his final journey to Addis Ababa.

The demolition of bridges and roadways once more held up the progress of the South Africans, and once more their engineers were swiftly able, through skill and improvisation, to bridge the gaps. Aosta was ensconced in a stronghold in mountains 10,000 feet high. The Italian fortress was, nevertheless, more a showpiece than a bastion. The 5th Indian Division was given the task of breeching it, and the plan was to stretch the thinly held Italian line until it broke.

The Allies gradually increased the pressure, and the Italians were jittery about their treatment at the hands of the Shifta irregulars of Ras Seyoum who were assisting the Allies. On May 19, the Italians surrendered to the sound of “The Flower of the Forest,” played by the pipers of the Transvaal Scottish.

This still did not mark the end of the campaign. Operations against scattered remnants of the Italian forces continued in the mountains until the end of November 1941, when the final battle was fought at Gondar. The Italians showed a fighting spirit to the bitter end but were simply not capable of winning against a modern enemy. The finale was as ignominious as the entry into Addis Ababa had been triumphal on May 5, 1936.

On May 5, 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie reached the green hills of Entoto and looked down on his capital city. Far from returning as the Conquering Lion of Judah, the little emperor was the last to enter his capital, an irony that was not lost on him. Being deeply religious, however, he believed the British were mere instruments of God, and His ways, inscrutable but infallible, had enabled Selassie to accept his burden with patience.

The emperor delivered an address before an honor guard from the 5th King’s African Rifles. “My people, do not repay evil with evil … do not stain your souls by avenging yourselves on your enemies …” He had returned.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments