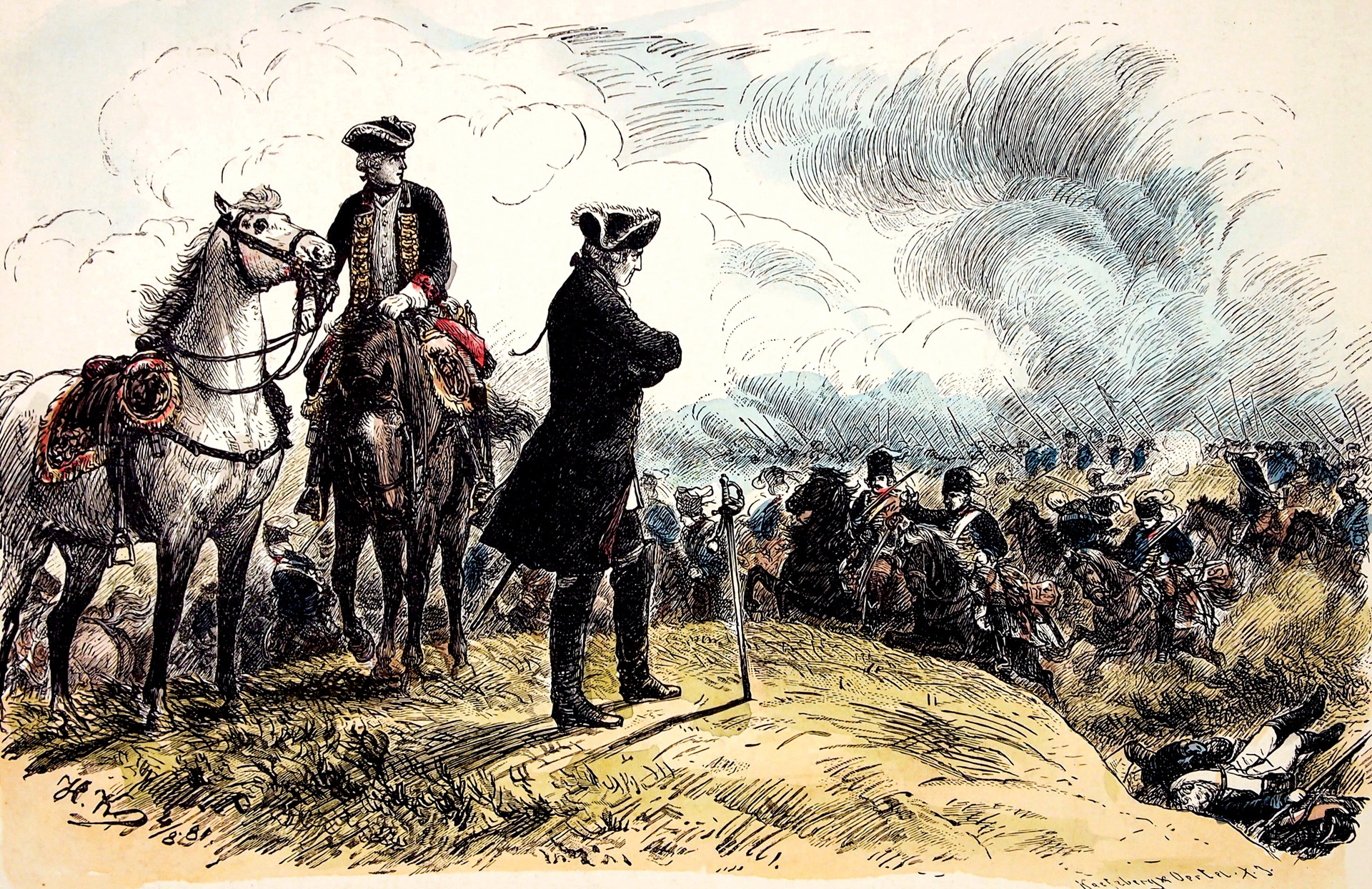

By Victor Kamenir

King Frederick II “The Great” of Prussia faced a formidable challenge at the outset of the campaign season in 1759. Armies of the coalition begun by France and Austria, which Russia had joined, threatened Prussia from four directions. Russia had dealt Prussia a stinging defeat at Gross-Jagersdorf on Aug. 30, 1757, and the following summer fought Frederick to a bloody standstill at Zorndorf on Aug. 25, 1758.

The once-vaunted Prussian army by 1759 was a shadow of its former self. The heavy losses in the battles of 1758 in particular had severely depleted Frederick’s army at all levels. The Prussian army had lost almost half of his officer corps and was hard-pressed to replace his rank-and-file troops and his regimental officers.

“I would fear nothing if I still had ten battalions of the quality of 1757,” wrote Frederick. “But this cruel war has killed off our finest soldiers, and the ones we have left do not even measure up to the worst of the troops at the outset.”

Frederick had become more cautious with his precious forces in the wake of these costly pitched battles. He made changes to his tactical doctrine to avoid full-scale attacks. His new doctrine called for using one wing of the army only, preserving the other to cover a retreat if the battle went badly. He also intended to concentrate his artillery to hammer one section on the enemy position before sending his infantry forward.

As he contemplated how best to parry the thrusts of the Austrians and Russians at the outset of the 1759 campaign, Frederick had to deal with the harsh reality that his vaunted infantry had suffered bloody repulses in recent battles and that he was hard-pressed to find capable commanders to lead Prussia’s smaller armies guarding the frontiers.

Frederick put a small Prussian army defending his eastern frontier under the command of the overly aggressive Lt. Gen. Johann von Wedell. Although a proven corps commander, von Wedell had no experience in independent command. Von Wedell proceeded to wreck the army by attacking the Russians in a strong defensive position.

At the Battle of Kay fought on July 23, 1759, in the Neumark region of Prussia, von Wedell lost 8,000 of 23,000 troops. The menace posed by the formidable Russian host led by Maj. Gen. Count Ivan Saltykov forced Frederick to personally take control of the situation in an effort to deal the Russians a smarting blow. Taking the cream of his forces, he set off to meet Saltykov in battle. He faced a daunting task, for he and his peers knew that attacking a numerically larger Russian army on ground that its commander had carefully chosen was a dicey proposition at best.

Frederick put his army to effective use and demonstrated considerable military skills during the eight-year-long War of the Austrian Succession. The war ended with Prussia gaining possession of a wealthy province of Silesia at Austria’s expense. Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa, who also was the Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia, could not accept the loss. She waited for an opportunity to renew the conflict and regain the surrendered territory.

A reshuffling of old alliances in 1756, which was known afterwards as the Diplomatic Revolution, reversed the traditional alliances in Europe. Instead of an alliance between France and Prussia, as had been in the case in the War of the Austrian Succession, Prussia’s major ally became Great Britain. Maria Theresa, who was deeply annoyed with Great Britain for forcing her to cede Silesia to Prussia, allied Hapsburg Austria with France and Russia. The Franco-Austro-Russian coalition also included Sweden, Saxony, and eventually Spain.

By making a pre-emptive strike on Saxony, Frederick had sought to prevent Austria from deploying its forces in Saxony, where they would be in an excellent position to threaten Berlin. The resulting Seven Years War became a protracted global conflict. It was for all intents and purposes two conflicts. One conflict was fought in Germany and Central Europe, where Prussia battled Austria and its allies. The other was overseas, in North America and the Indian subcontinent, where Britain fought France, which was assisted by Spain.

With the war on the European Continent against France relegated to a sideshow by 1759, Frederick focused on the dual threat posed by Austrian armies south of Prussia and Russian armies east of Prussia. He was keenly aware that if they combined some of their forces, it would pose a major threat to his kingdom.

After his victory at Kay in July 1759, Saltykov occupied Frankfurt-an-der-Oder on Aug. 1. But marching and countermarching in the blistering summer heat had taken its toll on the Russian army. The Russian cavalry in particular suffered greatly, losing a large number of horses. While resting his troops, Saltykov settled down to await the arrival of an Austrian column under Field Marshal Baron Ernst Gideon Laudon.

With the Prussian capital of Berlin 50 miles away, Frederick rushed south to prevent the Austrian corps from linking up with Saltykov. Although he marched his Prussian troops rapidly east in the blistering August heat, Frederick failed to prevent Laudon and Saltykov from joining forces. Laudon joined Saltykov on Aug. 8 in the Russian camp on the east side of the Oder River.

Saltykov, who was related to the late Russian Empress Anna, was a capable administrator and a cautious commander. He was capable of decisive action when needed, but was not the type of brilliant commander who would pursue and crush a beaten foe. Unlike many of his contemporary Russian commanders, Saltykov eschewed pomp. He cared greatly for his soldiers and had the trust and confidence of his subordinates. Yet he was deeply distrustful of foreigners. Sizing up Laudon, Saltykov believed the Austrian marshal to be lacking in substance.

Laudon, who was the son of a Swedish officer of Scottish descent, was suspicious of Saltykov and believed that the Russian commander was untrustworthy. Laudon had served with distinction in the Russian army during the War of the Polish Succession. After resigning from the Russian service in 1741, he applied to serve in the Prussian army, but Frederick rejected his application. Granted commission in the Austrian army, Laudon served with distinction during the War of the Austrian Succession. He was an excellent corps commander but lacked the operational expertise of an army commander.

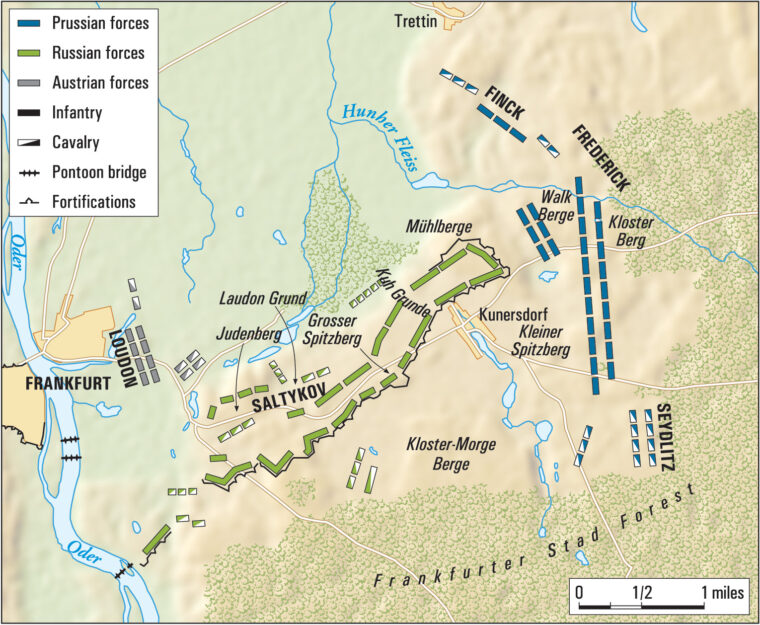

The terrain where Saltykov established his camp, which was in close proximity to the village of Kunersdorf three miles east of Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, greatly favored the defender. A chain of low hills, the tallest of which was barely 100-feet high, ran along the southwest-northeast axis. The hills were cut by two deep ravines, the Laudon-Grund and the Kuh-Grunde, which divided them into three sections.

The slopes of both ravines proved extremely difficult to traverse for both artillery and cavalry. At the southwest end of the range, the tall Judenberg was separated by the Laudon-Grund from the center. On the northeast end, the low treeless Muhlberg also was separated from the center by the Kuh-Grunde. The Grosser-Spitzberg knoll ran south from the central section and another knoll, Kleiner-Spitzberg, was located south of the Muhlberg.

The shallow waters of the Hunher Fleiss separated the Muhlberg from the heights south of the Trettin village. South of Kunersdorf was a chain of three ponds surrounded by marshy ground. The Frankfurter Forest, a dense growth of woods, formed a semicircle to the east of the Austro-Russian position. To the north and northwest was a marshy ground with scattered copses of trees and bushes called Elsen Busch, which was impassable to dense columns of troops.

The Judenberg was the key to Saltykov’s position, being close to the bridges over Oder and Saltykov’s lines of communications with the main Austrian army to the south. Although the Judenberg was the anchor of Allied positions in the southwest, the Muhlberg served the same role in the northeast.

Saltykov deployed the bulk of the Austro-Russian army facing north, in the direction of Frederick’s expected arrival. Saltykov positioned the 2nd Division, under Lt. Gen. Francoise Villebois, at Judenberg; the 1st Division, under Lt. Gen. Willem Fermor, on the Grosser-Spitzberg; and the 3rd Division, under Lt. Gen. Pyotr Alexandrovich Rumyantsev, in the center.

As for Lt. Gen. Alexander Mikhailovich Golitsyn’s Observation Corps, it was positioned on the Muhlberg. Golitsyn’s corps was composed primarily of recent recruits. The Austrian corps under Laudon and the bulk of coalition cavalry was near the Frankurt suburb of Rothes Vorwerk on the east side of the Oder. Several hundred Russians garrisoned the small fortress at Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, which was situated on the west bank of the Oder River. The coalition’s wagon trains, which were guarded by two Russian infantry regiments, were parked near the city.

The Russian army numbered 36,500 regular infantry and cavalry and 200 field guns, which included both six-pounders and 12-pounders. The oversized Austrian corps numbered 18,500 men with 48 guns, bringing the Austro-Russian total to 55,000 men and 248 guns. The Russians also had 5,000 Cossacks.

On the morning of Aug. 10, Frederick crossed to the east bank of the Oder at Gohliz with a force of 48,000 men and 140 guns. He advanced the following day to a point between the villages of Trettin and Bischofsee north of the Muhlberg. Russian hussars serving as pickets spotted the Prussian army and reported its arrival to Saltykov. After a short mounted skirmish with the Prussian hussars, the Russian horsemen fell back across the Hunher-Fleiss, burning a bridge behind them as they went. With the Russian pickets driven off, Frederick rode to reconnoiter the Austro-Russian positions.

From the heights around Trettin, Frederick could clearly see the Muhlberg and the Judenberg. The Russian forces occupying the Muhlberg were clearly visible, as well as some cavalry near the Frankfurt-an-der-Oder’s suburb of Rothes Vorwerk, but the main body of Russian forces remained hidden by the chain of hills. Based on his limited reconnaissance, Frederick believed that the Russian army was facing north and made the decision to attack the Muhlberg in a wide flanking maneuver from the north and east. He failed to ascertain the depth of Austro-Russian deployment and the placement of their reserves.

Although Frederick realized he would be outnumbered by the combined Austro-Russian army, he was confident of victory despite being fully aware of the diminished quality of his own troops. Even by his own acknowledgement, the Austrian army had greatly improved since the War of the Austrian Succession in the previous decade. The Russians had shown their toughness at Gross-Jägersdorf and Zorndorf. Still, Frederick remained contemptuous of his opponents, as well as overconfident in his own skills.

Closely following Frederick’s reconnaissance, Saltykov determined that the Prussian attack would most likely come from the east and southeast. Detailing a small number of light troops to watch Elsen Busch, he ordered his army to turn about and deploy facing south and southeast. Because he was primarily concerned with defending the key position at the Judenberg, Saltykov did not reinforce the Observation Corps on the Muhlberg. This left the corps’ five weak regiments in a vulnerable position.

Throughout the night, the Russian army labored to build entrenchments and artillery batteries facing in the new direction. They constructed abatis, felled trees with branches deliberately sharpened and pointed outwards, in the forest to slow the Prussian advance. They also built a chain of earthworks, which were connected by trenches, the entire length of their line. The trenches were only partially completed by morning.

As for the Russian artillery, Saltykov positioned five batteries on the Judenberg, as well as a strong battery facing east on the Grosser-Spitzberg. He ordered his troops to burn the village of Kunersdorf in order to establish a clear line of fire for the artillery.

On the evening of Aug. 11, Frederick completed his plan of attack. Lt. Gen. Frederick Aug. von Finck, who commanded a corps composed of eight battalions, was to make a demonstration of preparing for battle. Finck was to assemble his troops at 3:30 a.m and make a great deal of noise in his camp at Bischofsee. He also was to conduct a reconnaissance in full view of the Russians in order to give them the impression that an attack was being prepared from that direction.

Frederick instructed Finck to deploy his infantry corps, which was supported by a cavalry division, on the Trettin Heights at 5:00 a.m. An hour later, Finck was to advance a short distance toward the Muhlberg; however, Frederick explicitly instructed him not to attack the enemy until the main attack was well under way.

While Finck’s corps was stirring, the main body of Frederick’s army would march out from a separate camp at Bischofsee in two parallel columns. It would march under concealment of the Frankfurter Forrest and achieve a surprise by arriving behind Russian army’s eastern flank.

Frederick’s right column was to become the primary attack force. A cavalry division under Lt. Gen. Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz was to march at the head of the right column, and another cavalry division under Lt. Gen. Prince Eugen von Wurttemberg would bring up the rear. Once in place, Seydlitz was to deploy on the left of the right wing and Wurttemberg on the right. The right wing would then deploy in two lines and attack in the oblique formation, Frederick’s preferred method of attack, while the refused left wing, also in two lines, remained in support. Finck would launch his own attack once he heard the sound of the guns.

Frederick led the main body of the Prussian army out of its camp in the early morning hours of Aug. 12. The two columns began moving through the Frankfurter Forest at 3:00 a.m. As the Prussians filed into the woods from their camp at Bischofsee, Russian outposts spotted them at dawn and promptly sent the word to Saltykov. As for Finck’s corps, it set off at 5:00 a.m. bound for the heights south of Trettin. Meanwhile, Saltykov and Laudon, who had their troops in place, braced themselves for the Prussian attack.

The progress of the main Prussian army through the woods was slow. The grenadiers constituted the vanguard. The artillery crews had a challenging time navigating the narrow tracks of the forest. While the dense columns of Prussian infantry and cavalry slowly but steadily made their way through the forest, Frederick rode ahead to reconnoiter the Russian positions in the first light of day.

Gazing at the Muhlberg, Frederick realized that he was mistaken in his assumption that the Russians were facing northward. He realized that his army was marching directly at the enemy’s entrenched positions. To his vexation, he also realized that the ponds and marshy ground between Kunersdorf and the forest could be crossed in only two places.

Frederick adjusted his plans to address the situation. Instead of advancing directly at Kunersdorf, he would deliver the main attack with his left wing to the east of the ponds, while his right wing would advance against the Russian positions on the Muhlberg. The right wing would advance in conjunction with Finck’s corps. Meanwhile, the main body of the Prussian cavalry would redeploy to the left of the infantry’s left wing. Yet he still did not grasp that the Russian troops on the heights were split into several sections by the ravines.

Saltykov observed Finck’s corps at 8:00 a.m. advancing toward the Muhlberg and ordered the bridges between the ponds burned. After a few scattered shots, Russian pickets retired to the main line. Two Prussian batteries opened fire an hour later from their positions near Trettin. The Russian guns atop the Muhlberg returned fire on the Prussian batteries.

Delayed by its march through the thick forest, the main Prussian army began deploying east of the ponds at 10:45 a.m. In front of the Prussian right wing, a vanguard of six grenadier and two fusilier battalions began deploying in preparation for assaulting the Russian positions on the Muhlberg. At the same time, the Prussians began setting up their heaviest guns on the knolls south and southeast of the Muhlberg. Even though Prussian intentions were clearly obvious, Saltykov still did not reinforce this position. Instead, he deployed more troops on the Grosser-Spitzberg by shifting reserves into the second line and deploying 15 squadrons of dragoons and horse grenadiers near the Kuh-Grunde.

Frederick ordered the bulk of his artillery to commence firing 45 minutes later. Sixty Prussian guns, which their crews positioned in an arc around the Muhlberg, began pounding the Russian infantry in their entrenchments. The Russian artillery, greatly outnumbering the Prussian artillery, had some 100 pieces on the left wing alone. The Russian battery on the Grosser-Spitzberg fired on the Prussian forces deploying in front of them, but its effectiveness was reduced by the distance. The two sides traded salvos for the next hour. The Russians on the Muhlberg suffered the most in the exchange. Saltykov finally reinforced the Observation Corps by shifting six Austrian battalions from the Judenberg closer to the Muhlberg.

Judging the time to be right for an attack on the Muhlberg, Frederick ordered his vanguard to advance at 12:30 p.m. against the objective. Eight Prussian grenadier battalions in two lines began climbing the slopes of the Muhlberg. As the Prussian grenadiers came within 100 paces of the Russian lines, they were greeted by musket volleys and grapeshot.

The Prussians, who were undeterred by the storm of artillery fire, replied with discipline and deadly musket volleys of their own. Their accurate fire sowed confusion among the Russian troops, whose resolve had already been shaken by the merciless pounding of the Prussian artillery. Leaving behind scores of blue-coated bodies, the Prussians then charged with fixed bayonets, attacking the regiments of Golitsyn’s Observation Corps from the front and right flank. The Prussians smashed the Grenadier Regiment of the corps, which, as it fell back, carried away two musketeer regiments with it.

These regiments, which were taking a pounding from the Prussian guns, attempted to reform, but they were too badly disordered. They fled towards Elsen Busch, abandoning 42 guns as they went. Saltykov dispatched two fresh Russian regiments in an effort to shore up Golitsyn’s collapsing position. Although the Russian counterattack temporarily halted the progress of the attacking Prussian units, the reinforcements were not able to retake the Muhlberg.

While Frederick was redeploying his artillery and reinforcing his men on the Muhlberg, Golitsyn rallied several regiments of the Observation Corps and established a new defensive line. The new line was perpendicular to the previous Russian deployment on the Muhlberg. The Prussians resumed their attack, though, and once again dislodged and disordered the Russians.

Seeing the Observation Corps in full retreat, Saltykov ordered forward 12 companies of Austrian grenadiers, reinforced by a Russian grenadier regiment, to check the Prussian juggernaut. But the Austro-Russian counterattack faltered in the face of determined resistance by the reinforced Prussian vanguard. As they fell back, the grenadiers disordered two more Russian regiments coming up in support. Prussian shells crashed among the Russian cavalry posted southwest of the Muhlberg, and they also withdrew to avoid further losses.

The Prussian vanguard, which was eager to exploit its success, descended the Muhlberg in preparation for an attack on the hilltop on the far side of the Kuh-Grunde ravine. But two more fresh Russian regiments, who were supported by Austrian grenadiers, entered the fight and succeeded in repulsing the attacks of the exhausted troops of the Prussian vanguard.

At that point, Frederick assembled a large column on the Muhlberg, reinforced by Seydlitz’s cavalry, in preparation for an assault on the Grosser-Spitzberg across the Kuh-Grunde. He ordered forward a Prussian battery to the eastern edge of Kuh-Grunde to support the Prussian infantry.

The Russians redeployed facing the Muhlberg in two lines. Austrian artillery moved into position to support them. The first Prussian infantry assault across the Kuh-Grunde was met by a hail of enemy musketry and grapeshot at close range. The Prussians recoiled in the face of the blistering fire.

The Prussian heavy cavalry then went into action. The Prussian cuirassiers, who attacked uphill, struck the Novgorod Musketeer Regiment in flank. The successful flanking maneuver dislodged the Russian musketeers from their position. The Prussian cuirassiers continued on to the Grosser-Spitzberg, where their advance came to an abrupt halt in the face of concentrated Russian artillery fire and musketry. At that critical juncture, Laudon and Rumyantsev personally led a spirited counterattack. Assembling one Austrian and two Russian dragoon regiments, they succeeded in dislodging the Prussian cuirassiers from the Grosser-Spitzberg.

While the Prussian vanguard descended the Muhlberg and attacked the Kuh-Grunde, the main Prussian army advanced forward in oblique order with the right wing forward. The regiments of the right wing, following the vanguard through destroyed Russian entrenchments, became compressed and disorganized as they navigated the hilly terrain. The Russian battery located on the Grosser-Spitzberg knoll pounded the tightly packed Prussian infantry formations, inflicting heavy casualties on them.

The Prussian right wing halted to reorganize. In so doing, it denied the Prussian vanguard the immediate assistance it needed, for it was taking a severe beating in the Kuh-Grunde. The casualties were so heavy among the Prussian grenadiers that after the battle, the survivors of the six grenadier battalions were consolidated into three battalions.

Austro-Russian resistance was stiffening by that point in the battle as a result of fresh infantry and artillery arriving from the right wing. Saltykov established a new defensive line from the Kuh-Grunde to the village of Kunersdorf. When the reorganized Prussian right wing came forward, it was taken under fire by Russian artillery. Counterattacking Russian units beat back multiple assaults by the Prussians. Casualties steadily mounted, with both sides suffering staggering losses.

Frederick brought up fresh Prussian batteries and added their weight to the carnage. The Apsheron and Rostov regiments of the Russian army, protecting the battery at Grosser-Spitzberg, suffered devastating casualties. In the confusion of the battle, the Russians mistook the Austrian Baden-Baden regiment, which wore uniforms that were a lighter shade of blue than the Prussians, for the enemy and fired into their ranks.

Finck’s corps was delayed advancing over the marshy ground northwest of the Muhlberg to support the Prussian right wing. It was not until 2:00 p.m. that it finally advanced against the coalition forces on the Kuh-Grunde.

With his right wing unable to carry Kuh-Grunde and the left wing still uncommitted, Frederick sent Seydlitz forward with 16 squadrons of dragoons and hussars. Seydlitz moved his cavalry through the ponds, deployed it in full view of the Russians, and charged the trenches occupied by Russian regiments on Grosser-Spitzberg.

Prussian artillery and musketry emptied scores of saddles as 11 Austrian and four Russian cavalry squadrons counterattacked the Prussian horsemen. However, a strong Austro-Russian counterattack drove back the Prussian cavalry. The Austro-Russian cavalry continued its advance, routing the Prussian infantry on the right wing. Their advance eventually ground to a halt in the face of a counterattack by a small number of Seydlitz’s cavalry, which had reformed.

After a brief lull, fighting flared anew at 3:30 p.m. in the blood-soaked ground of the Kuh-Grunde ravine. The slow progress of Finck’s troops through the marshy ground gave Saltykov plenty of time to ascertain the direction of the fresh Prussian attack. As Finck’s corps added its weight to the fight, it was able to temporarily force back the Russian left wing. But four regiments of Russian infantry, which were backed by Russian guns, managed to stop the advance of Finck’s troops.

As the inconclusive and bloody fighting was raging around Kuh-Grunde, several Prussian generals, including Frederick’s brother Prince Henry, a capable soldier in his own right, advised Frederick to halt the fighting. By that time, the Prussians had firm control of the Muhlberg. The majority of the Prussian generals concurred and urged the king to renew his attack the following day.

Soldiers on both sides suffered horribly from the blistering heat, but the Prussians actually suffered more than the coalition forces given that they had conducted long marches the previous day in order to attack the Austro-Russian position. Frederick believed his army could still carry the day, and he rejected the advice of his subordinates. He then moved his remaining reserve, the infantry of the left wing, into position to continue the attack.

The infantry of the left wing deployed in the confined space hemmed in by Kunersdorf and the chain of ponds south of the village. Marching through the cramped terrain and the ruins of Kunersdorf, the units of the Prussian left wing soon became disordered. As soon as they emerged from the village, the Russian guns on the Grosser-Spitzberg blew gaping holes in their tightly packed ranks. The Prussian battalions attacked several times but were hurled back in disarray by the massed Russian artillery.

Frederick rode from his observation post on the Kuh-Berg hill to rally the troops at Kunersdorf. He ordered that more artillery be brought up before riding back to Kuh-Berg, where he remained for the rest of the battle as the infantry continued fruitless attacks.

While the Russians and Austrians remained steadfast on the hills west of Kunersdorf, they were taking heavy casualties from Prussian artillery. The Austro-Russian line began to waver at 4:30 p.m., and some of the units began to give way. With the threat to Judenberg eliminated, Saltykov moved the bulk of troops from the right wing to Grosser-Spitzberg. Nine Russian regiments charged the disordered Prussians milling around Kuh-Grunde and drove them past Kunersdorf. At the same time, Finck’s exhausted battalions broke off their attacks and retreated without being harassed by the Russians.

While the fighting raged around Kunersdorf, a Prussian detachment of three infantry battalions and 16 cavalry squadrons under Maj. Gen. Johann Jakob von Wunsch, which had been dispatched on their mission early in the morning, crossed to the west side of the Oder River and forced their way into Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, capturing the small Russian detachment there.

With no fresh infantry to feed into the battle, Frederick ordered the last of his cavalry to relieve the pressure on his embattled infantry. Seydlitz, who was standing by his side, suffered a wound in his right arm and turned over his command to the Prince of Wurttemberg.

The Prussian cavalry on the right advanced over the confined space across the slopes of the Muhlberg and came under Russian artillery fire. The cannon fire forced a Prussian dragoon regiment to retreat, and the Prince of Wurttemberg was carried wounded from the field. Maj. Gen. Georg Ludwig von Puttkamer, leading his hussar regiment in a futile attack against the Russian left flank, tumbled dead to the ground.

A regiment of Prussian cavalry was equally unsuccessful, and the cavalry of both wings, as well as that of Finck’s corps, rallied at the Muhlberg under command of Lt. Gen. Dubislav Friedrich von Platen. They advanced against the Russian left wing, where the Prussian infantry was still heavily engaged west of the Kuh-Grunde.

The badly fatigued Prussian infantry on the left withdrew at 5:30 p.m. to the east side of the Kuh-Grunde. Seeing the infantry retiring, Platen sent five dragoon squadrons against the Gross-Spitzberg to cover the retreat, but the cavalry was quickly broken by the Russian artillery fire.

At this time, Austro-Russian cavalry charged that section of the Platen cavalry that had crossed to the west side of the ponds. While the cavalry fought it out near the Blanken-See pond, Frederick rallied his infantry east of Kunersdorf and personally led them forward. Frederick had two horses shot from under him in quick succession. He nearly lost his life to a Russian bullet, but it flattened itself against a gold tobacco case that he carried in his coat pocket.

The Prussian infantry descended again into the Kuh-Grunde and tried to scale the opposite side. In a desperate attack, the Prussians pushed back two Russian regiments, but the entire Prussian line began to waver when three fresh Russian regiments arrived to restore the situation.

The Prussian cavalry finally broke at 6:00 p.m. The defeated horsemen fled pell-mell to the rear. On the heels of their retreating cavalry, Prussian infantry began quitting the Kuh-Grunde and the Muhlberg and withdrawing to Bischofsee. The fleeing cavalry and infantry were followed by artillerymen, who abandoned the majority of their guns to the victorious Allies.

The Allied cavalry pursued the fugitives, mercilessly sabering those falling behind. Frederick tried in vain to rally several regiments to cover the retreat, but he was only able to gather 600 men from several units around him, as well as an artillery battery.

“Lads, do you want to live eternally?” Frederick shouted to his men as he seized a flag to lead them forward again. Maj. Gen. Christian Friedrich von Diericke’s Fusilier Brigade, the one brigade that remained intact, formed itself into a square to survive the ordeal. But the Russian cavalry shattered the formation and overran it. The small band around Frederick retreated, abandoning the artillery battery as it went.

The Austro-Russian heavy cavalry halted, leaving the pursuit of the beaten Prussians to Lt. Gen. Count Gottlob Heinrich Curt von Totleben’s light cavalry. Totleben, a German-born general in Russian service, chased the Prussians with his Don Cossacks and Russian hussars.

Frederick made one last-ditch attempt to save his remaining forces. He sent in two elite cuirassier squadrons of the Leibregiment to delay the Russians, but before the elite troopers had a chance to engage the enemy, they were attacked by the Cossack Chuguyev Regiment and routed.

The Cossacks, who were armed with lances, attacked the elite Prussian cuirassiers, threw them back, captured their flag, and took their commander prisoner. In so doing, they succeeded in repelling the last, desperate attempt by Frederick to save the remnants of his army. The Cossacks then surrounded Frederick and his staff. Were it not for the timely intervention of some of the Zieten Hussars, Frederick would have been captured.

The one glimmer of success in the campaign occurred when von Wunsch’s troops withstood Russian attempts to retake Frankfurt-an-der-Oder. But even that success was short-lived. When Saltykov threatened to bombard the city, Wunsch promptly capitulated to save his troops. Saltykov allowed Wunsch’s troops to march out rather than go into captivity, and they rejoined Frederick’s remaining forces the next day.

The remnants of the Prussian army still under colors—numbering somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000 men—retreated to the Oder bridges. Frederick gathered up his stragglers over the course of the next several days and set about reorganizing his army.

“My coat is riddled with musket balls, and I have had two horses killed beneath me,” Frederick wrote the day after the battle to his foreign minister Count Karl Wilhelm Reichsgraf Finck von Finckelstein. “It is my misfortune to be still alive. Our losses are very great…. At the moment that I am writing, everybody is in flight, and I can exercise no control over my men.”

Frederick lost 19,000 men killed, wounded, missing, and captured, as well as 170 artillery pieces and 28 colors captured. It was the worst defeat of his career. The Russians suffered 13,477 killed and wounded, while the Austrians lost 1,398 killed and wounded for a total of 14,875 coalition casualties. For his victory, Saltykov was promoted to marshal.

As the news of the catastrophic defeat reached Berlin, there was widespread panic, and even a half-hearted offensive on the capital would have brought the end of the war. Yet the Allies remained largely static, for they were struggling to recover from their own heavy losses. Frederick vowed to defend Berlin if the Austrians and Russians converged on it.

“We’ll fight them—more in order to die beneath the walls of our own city than through any hope of beating them,” Frederick wrote in the aftermath of the battle. But that last stand never came to pass. In what became known as the “Miracle of the House of Brandenburg,” the Austrian and Russian forces did not advance on Berlin. Laudon moved off to rejoin the main Austrian army, while Saltykov waited for the arrival of supply trains to replenish his ammunition.

Kunersdorf is remembered not only as Frederick’s greatest disaster, but also as Russia’s greatest military victory in the 18th century.

The Seven Years War continued with the conflict steadily tipping in favor of the coalition arrayed against Prussia. “We ought now to think of preserving for my nephew, by way of negotiation, whatever fragments of my territory we can save from the avidity of my enemies,” Frederick wrote to Finckelstein on January 6, 1762.

When he wrote the letter, Frederick was as-yet unaware of the sudden death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia the day before. Her German nephew Duke Karl Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp ascended to the Russian throne as Tsar Peter III. The new Russian monarch hardly spoke Russian and was a staunch admirer of Frederick. Peter immediately halted Russian operations against Prussia, which led to the eventual collapse of the anti-Prussian alliance. The war ended with Prussia in possession of roughly the same territory as at its commencement.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments