By John Pezzola

In the early morning hours of September 8, 1781, drums rolled and fifes played in Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene’s camp in the High Hills of southeastern South Carolina. Sleepy soldiers dragged themselves from their tents to prepare for the day ahead. It was only 4 am, and already Greene’s forces were preparing to have breakfast and then move out to engage enemy forces under British Lt. Col. Alexander Stewart a few miles away alongside the Santee River at Eutaw Springs. The morning was clear and sunny and showed signs of a hot and humid day to come.

Greene’s move was the next jump on a grand chessboard of strategy that had changed greatly in the four years following the British defeat at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777. There Crown forces failed to isolate New England from the rest of the American colonies and destroy the rebellion one piece at a time. With the commencement of France’s involvement in the war, Great Britain would need to pull her regular forces from the North American mainland in order to secure her lucrative colonies in the West Indies. Given this precarious state of affairs, the British government revised its strategy. By November 1778, the focus shifted to the southern theater of the war, where the British hoped to gain Loyalist support to supplement their troops. By placing a large land force in the South, the British wanted to divide American attention and stretch the rebels’ supply and troop lines to the breaking point.

A similar strategy had been attempted in 1775 and 1776, but had met with failure because of an overreliance on locally raised Tory forces without the backing of British troops. Subsequent defeats at Great Bridge, Virginia, and Moore’s Creek Bridge, North Carolina, had discouraged Loyalist activity in the South. By mid-1778, however, retaking the southern colonies again became a military and political priority for the British. The capture of Savannah, Georgia, in 1778, and Charleston, South Carolina, in 1780, along with the destruction of Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates’s Continental army at Camden, South Carolina, in August 1780, had created a serious threat for the Americans. To further complicate the situation for the British, outrage over the massacre of Virginia forces at the Waxhaws by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s notorious British Legion further heightened patriot passions.

Ultimately, the British would have to rely on small strike forces to curb colonial opposition and establish interior outposts to maintain lines of communication. Following the disastrous blow to American forces at Camden, General George Washington had dispatched Greene to take command in the South. Greene faced a momentous task in stopping the British juggernaut. With recent successes and growing confidence, the British army launched a new campaign into North Carolina. Lord Charles Cornwallis dispatched Major Patrick Ferguson, his recently appointed inspector of militia, to cover the British left flank with a large Tory contingent. The overconfident Ferguson marched into the back country of North Carolina where American frontiersmen responded to the threat by completely annihilating Ferguson’s command at the Battle of King’s Mountain in October 1780.

Greene’s Insurgency in the Carolinas

Following his defeat at Camden, Gates had begun to rebuild the army. Once Greene entered the theater, he continued the effort, carefully reshaping the remains of the shattered army into a cohesive new fighting force. While reconstructing his forces, Greene made use of partisan units that had been operating in the theater since the summer of 1780, an unorthodox strategy that violated the principle of concentration so dear to the thinking of George Washington. Greene divided the army into two parts, one commanded by Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan and the other by Greene himself. His reason for dividing his forces was twofold: he hoped that each smaller corps would be able to procure supplies more easily, and he wanted to force Cornwallis to divide his own forces to deal with two antagonists at once.

In January 1781, a British force detached from Cornwallis’s main army under the command of the infamous Tarleton suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Cowpens, in the piedmont region of South Carolina. Continental troops led by Morgan killed 100 English soldiers, wounded another 229, and captured more than 600. American losses were a mere 12 killed and 60 wounded. Greene followed Morgan’s victory with a strategic victory of his own at Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, on March 15. Cornwallis was now in a precarious situation and had no choice but to move to the coastal town of Wilmington to be resupplied.

Greene’s insurgent strategy became one of depriving the British of supplies, draining manpower, and cutting communications—a method that did not depend on tactical victories. Following the Guilford Courthouse campaign, Greene focused on taking back territory controlled by the Crown so that at the conclusion of the war, the British could not claim it in a settlement. On April 2, Greene relayed his plans for the upcoming campaign to American General Baron Von Steuben while camped at Ramsay’s Mill, North Carolina. “I think it will be our true plan of policy to move into South Carolina, not withstanding the risks and difficulty attending the maneuver,” wrote Greene. “This will oblige the enemy to follow us or give up their posts there. If they follow us, it will relieve this state.”

The High Hills of the Santee

While Greene made a push back into South Carolina, Cornwallis decided to move northward into Virginia and disrupt Greene’s supplies. Cornwallis left Lt. Col. Francis Lord Rawdon behind at Camden. Following the American siege of Fort Motte and the capitulation of Fort Watson, which resulted in the severing of the line of communications between Charleston and Camden, Greene and Rawdon met at Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25. British forces took possession of the field, but at a heavy price.

Despite another tactical British victory, Rawdon began to withdraw, moving out of Camden and establishing a base camp in the High Hills of Santee along the way to Charleston. Greene immediately dispatched his partisan corps to harass British supply lines and capture critical communication outposts. With the constant marauding of partisan bands, augmented by Continental infantry and artillery, British outposts in the interior were forced to evacuate. Rawdon sent dispatches indicating the dire situation, but British strongholds at Fort Ninety-six and Fort Granby never received Rawdon’s orders to fall back to Charleston. Following Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter’s capture of Orangeburg, partisan Colonel Francis Marion moved his force to capture Georgetown, while Andrew Pickens and Henry Lee moved toward Augusta, Georgia.

By May 22, Greene was laying siege to Fort Ninety-six, commanded by Loyalist Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger. Rawdon used fresh troops just arrived from Ireland to bolster his forces and relieve the siege. Rawdon was unaware of Cornwallis’s advance toward Virginia, and once Cornwallis entered North Carolina, there was no open line of communication with South Carolina. To make matters worse for Rawdon, he was ill throughout the campaign and had no choice but to relinquish his command to Lt. Col. Alexander Stewart.

Greene integrated Marion’s and Pickens’s partisans with regulars such as Lee’s Legion and Lt. Col. William Washington’s 3rd Continental Light Dragoons. Greene was able to keep communications open and ensure the flow of supplies to his army, while the British had no alternative but to use soldiers to provide constant security for their own communications and supply lines, reducing the number of men available for combat operations.

Greene’s forces, although successful, were suffering from the effects of the intense summer heat and humidity. Before Greene could consider taking on Stewart, he wanted to reinforce his army and allow them time to recover from the extensive marching. Greene marched his army to the High Hills of the Santee, where he encamped and planned his next move.

Closing in on Stewart at Eutaw Springs

While Greene’s army recuperated, Lee’s Legion was sent to forage and Marion’s men continued cutting enemy communications. Hoping to bolster the number of troops at his disposal, Greene looked to the “Over Mountain Men” who had defeated Ferguson at King’s Mountain, but renewed hostilities with pro-British Cherokees prevented them from supporting Greene. Virginia promised to send Greene 2,000 militiamen, but because of the new British threat in the state, those troops were never sent.

Greene felt it was imperative to use the available time to organize and retrain his army. On Tuesday, August 21, he ordered his troops to drill by brigades, with one round of blank cartridges fired by platoon from right to left. There was constant pressure on the Continental troops to utilize traditional European linear tactics in the face of the enemy. Meanwhile, Stewart was forced to move his British army into the hills between the Wateree and Congaree Rivers to resupply without risking an engagement.

By August 27, Greene received intelligence that Stewart was camped along the Santee at Eutaw Springs. Finally reinforced, Greene marched to Friday’s Ferry and crossed the Congaree at Howell’s Ferry where Pickens’s militia and Lt. Col. William Henderson’s South Carolina state troops joined him. Including reinforcements from North Carolina, Greene’s entire force amounted to 2,300 men.

On the night of September 6-7, Marion met Greene’s command at Laurens’s Plantation, about seven miles from Eutaw Springs. Greene now was ready to move on Stewart and surprise him before Stewart could establish a permanent camp. Stewart’s pickets had not noticed any unusual rebel activity and Stewart himself confessed that he was utterly unaware of the rebels’ nearness, despite every exertion to gain knowledge of the patriots’ location.

At 10 am on September 7, Greene issued his men a gill of rum to lift their spirits and had them draw one day’s rations prior to advancing on Stewart. The order of battle was revised to include Marion’s brigade in the front line, with other militia units to follow. Lieutenant William Gaines, who commanded two three-pounder field pieces, followed Marion, who was supported in turn by North Carolina militia under the command of Colonel Francis Malmedy.

Stewart’s camp at the springs was near a two-story brick mansion owned by Patrick Roche, with a large palisaded garden on its right facing Eutaw Creek. The mansion sat on the north side of the river road. Stewart’s forces were encamped on both sides of the road in an open field. The road leading to Charleston branched off behind the British encampment. Between the two roads there was a large ravine. To the front of Stewart’s position, there were about 10 acres of cleared land, and beyond that a forest of oak and cypress trees sat on either side of the road.

One Mile Within Stewart’s Camp

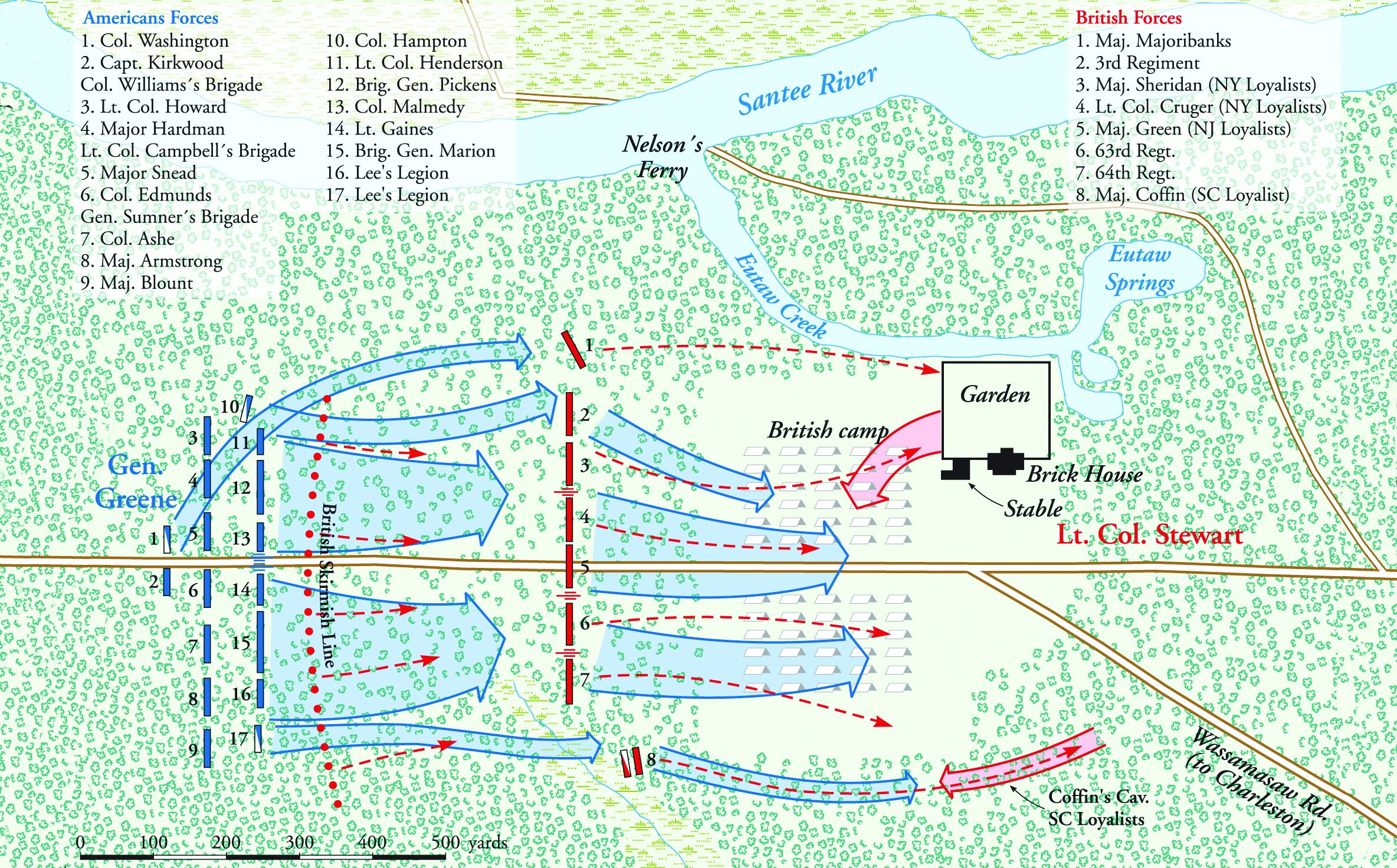

Early the next morning, Greene marched his forces in two columns with artillery at the head of each. Lee’s Legion made up the vanguard, with a contingent of South Carolina state troops followed by a second column consisting of North and South Carolina militia under Pickens, Malmedy, and Marion. Next came three brigades of Continentals from Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina, supported by two six-pounders. A reserve force composed of Washington’s dragoons and a Delaware company of Continentals under Captain Robert Kirkwood made up the rear guard.

At 6 am, Lee ran into a foraging party of both mounted and dismounted men from Stewart’s force. He immediately deployed his Legion infantry across the road and the South Carolina state troops under Henderson moved into place north of the road. Following the first shots from Lee’s force, Stewart’s foraging party withdrew, losing over 400 men captured by the rebels.

Around the same time, Stewart detached Major John Coffin, who commanded about 140 infantry and 50 mounted troops, to gather intelligence regarding the enemy’s whereabouts. Coffin mistook Lee’s force for a group of militia and began to skirmish with the South Carolina troops. Coffin sent word to Stewart that the enemy was about four miles away from Stewart’s camp at Eutaw Springs. Coffin’s cavalry pressed the enemy who discharged a volley, knocking down some of Coffin’s troopers. Coffin turned and headed back toward the camp. Captain Robert Kirkwood and the Delaware Continentals advanced until they were within one mile of Stewart’s camp.

With Coffin driven off and returning to camp, the engagement alarmed Stewart, who deployed his forces into line in the wooded area in front of the camp. “Finding the enemy in force so near me, I determined to fight them as from their numerous cavalry a retreat seemed to me to be attended with dangerous consequences,” Stewart reported later. “I immediately formed the line of battle with the right of the army to the Eutaw branch and its left crossing the road leading to Roche’s Plantation, leaving a corps on a commanding situation to cover the Charleston road and to act occasionally as a reserve.”

The Battle of Eutaw Springs Begins

Stewart placed the 3rd Regiment of Foot (The Buffs) near the creek. To the north of their position, a 300-man contingent of light infantry and grenadiers under the command of Major John Majoribanks was deployed to protect the right flank in a patch of tangled woods on the bank of the creek. The center of the line was composed of Loyalist units from New Jersey and New York extending across the River Road, with the 63rd and 64th Foot on the far left.

Although Stewart’s right was secure, his left wing on the south was exposed. He sent Coffin’s cavalry to cover that flank. Stewart realized that his mounted forces were inferior to Greene’s and attempted to compensate for this handicap by designating a predetermined strongpoint. At the first sign of misfortune, Loyalist Major Henry F. Sheridan was to throw his New York troops into the Roche House and cover the army from the upper windows.

Stewart commenced the action by deploying skirmishers and a field piece about a mile in front of his main line. It was about nine o’clock when British forces arrived in Greene’s front and Marion’s men promptly began to drive them back. Lieutenant Gaines’s artillery was quickly brought forward and fired into Stewart’s forces. At this point, Greene’s first line consisted of Marion’s militia and Lee’s troops on the right, Malmedy’s North Carolina militia in the center, and Picken’s militia and Henderson’s South Carolina state troops on the left.

Lee made an attempt to move around Stewart’s left flank but was repulsed by the 63rd Regiment and a field piece. Gaines then moved his artillery forward to support Lee. When Gaines blasted the British line with canister they became disorganized and began to panic. Gaines continued firing until the trunion straps on the cannon broke and disabled the gun.

While militia under Marion and Pickens were helping to hold the flanks of the first line, Malmedy’s North Carolina militia in the center started to falter. As a result of the intense fighting, men in the front line were beginning to run low on ammunition, and it was only a matter of time before the line would collapse. Seeing the militia in the center struggling, Greene ordered General Jethro Sumner’s brigade of North Carolina Continentals forward from his second line to replace Malmedy’s North Carolina militia. Lee provided a description of the precarious state of the first line prior to Sumner’s arrival: “The sixty-third and the Legion infantry were warmly engaged,” he wrote, “when the sixty-fourth, with a part of the center, advanced upon Colonel Malmedy, who soon yielding, the success was pushed by the enemy’s left, and the militia, after a fierce contest, gave way, leaving the corps of Henderson and the Legion infantry engaged, sullenly falling back.”

Sumner’s brigade, consisting of three battalions, kept up a vigorous fire against the 63rd and 64th Regiments. The North Carolinians were able to push back Stewart’s command and hold the southern flank with Lee’s Legion. Stewart stopped Sumner’s advance by bringing into line the corps of infantry posted in the rear of his left wing, accompanied by Coffin’s cavalry. The bayonet-wielding 63rd and 64th Regiments began to push forward into Sumner’s men, many of whom were without bayonets themselves and had no choice but to withdraw, creating a gap in the American line.

Henderson’s South Carolina state infantry, on Green’s left flank, was taking tremendous fire from the Buffs, whose line extended beyond Henderson’s left flank. When Henderson was wounded and taken off the field, his men began to panic. Colonel Wade Hampton, commanding a contingent of mounted South Carolina state troops, took command and restored order.

Greene’s Lost Opportunity for Victory

Greene now moved forward Colonel Otho Williams’s Maryland Brigade of two battalions under Lt. Col. John Eager Howard and Major Henry Hardman. “Let Williams advance and sweep the field with his bayonets,” Greene commanded. Moving with the Marylanders was a battalion of Continental troops from Virginia. At this point, the American main line consisted mainly of Lee’s Legion infantry, Maryland and Virginia Continentals, and the remnants of Henderson’s South Carolinians under Hampton.

Williams’s Marylanders delivered a heavy volley into the British, who were falling back. The Maryland troops kept advancing even while sustaining heavy casualties among the officers. One by one the redcoat regiments gave way and fled through their camp to the cover of the brick house. A crushing American victory seemed imminent. But as the Patriot forces pushed through, some of the militia and Continentals stopped to plunder the British camp, while others were held up by Sheridan’s command stationed in the brick house. The momentary check allowed Stewart time to rally his forces.

Greene, for his part, was unaware of the developing situation in the British camp and Coffin’s mounted force was still holding its ground on the British left flank. Lee believed that success hinged on removing Coffin so he sent for Major Joseph Eggleston to lead the Legion cavalry against Coffin’s mounted troopers. Eggleston had already been deployed, but according to Lee, he was held back from attacking by orders “officiously communicated to that officer as from the general, when in truth he never issued such orders.” Otherwise, said Lee, he would have been ready to inflict a death blow on the enemy.

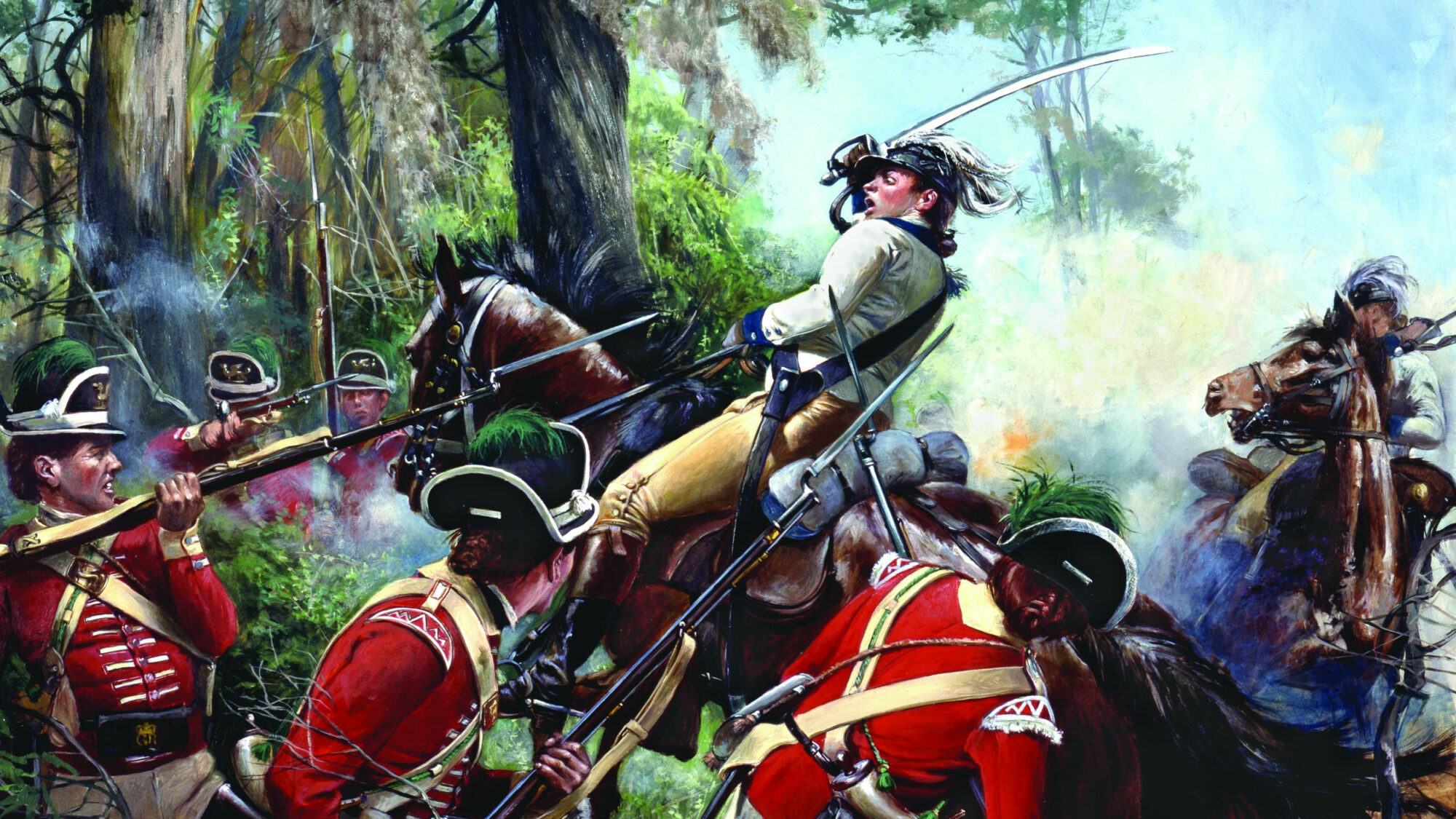

On the far left of the American line, William Washington’s 3rd Continental Dragoons charged Majoribanks’s light infantry and grenadiers, who were destroying Henderson’s battalion from the cover of a blackjack thicket. Washington’s horsemen could not penetrate the heavy underbrush and were repulsed. Washington’s horse was killed and, unable to free himself, Washington received a bayonet wound and was captured.

Following the repulse of Washington, Majoribanks fell back to the protection of the brick mansion. On the British left, Coffin placed himself in a field on the south of the Charleston road. “In our pursuit we took three hundred prisoners and two field pieces of artillery,” he reported. As Lee’s forces cleared the camp, they entered an open field and the British immediately opened fire from the mansion. Some of the Legion infantry continued to press forward and attempted to enter the house before the door could be barricaded.

Before the American troops could force their way in, the door was shut. The Maryland battalion began to push through the field heading toward the ravine, along with Kirkwood’s Delaware troops taking position on the right of the house. Majoribanks to the north and Coffin’s forces to the south continued to pour gunfire into the American ranks. While Stewart organized a last-ditch defense, he sent his wounded down the road toward Charleston. Greene ordered his artillery, which now included two captured British six-pounders, to breach the mansion but Loyalists in the house decimated the gunners.

When Greene finally realized that the majority of his forces were caught up in pillaging Stewart’s camp, it was obvious that the American advance was checked. As Stewart continued to rally his men, Greene sent the Legion cavalry to the right to attack, only to be checked by Coffin. Stewart and Majoribanks then counterattacked, pushing Greene’s army back, with Majoribanks wounded in the process. Greene quickly positioned Hampton’s mounted force to cover his retreat.

The Battle of Eutaw Springs: Tactical Defeat, Strategic Victory

By the end both sides were battered. It could be said that Greene lost the engagement tactically because he withdrew from the field. While the exact numbers are not clear, Greene probably left behind 119 dead, 382 wounded, and 78 missing. Greene, who was concerned about the prospect of Stewart reorganizing and counterattacking, dispatched Marion and Lee to keep a close watch on Stewart and to attack if the opportunity presented itself. Somewhat chagrined, Lee and Marion observed the British destroying thousands of muskets and pouring good British rum into the inky waters of the creek.

Stewart’s casualities are estimated to have been 85 killed, 297 wounded, and 500 captured, a staggering 42 percent. He was in a precarious situation and needed to withdraw quickly. In the course of doing so, the wounded Majoribanks died during the retreat to Charleston. The last major British army operating in the field had been badly mauled, and for this point alone Greene’s campaign could be considered a strategic victory.

The engagement at Eutaw Springs, the last land battle in the Carolinas, mirrored many other engagements in the southern theater, with the Americans again suffering a tactical defeat, but the British withdrawing. After all their hard campaigning and tactical victories, the British were left holding only the cities of Charleston and Savannah. The British continued their retreat toward Charleston, while Greene dispatched Sumter and Hampton to round up remaining Tory forces and prevent their aiding the British forces moving toward Charleston.

On the same day that the Battle of Eutaw Springs took place, George Washington moved his forces out of Williamsburg and began advancing toward Yorktown. Eutaw Springs showed the world that Great Britain no longer held the interior of South Carolina and Georgia and was incapable of conducting operations to retake it. In fact, British strongholds in the South now consisted merely of coastal positions. Greene not only forced Cornwallis out of North Carolina; he had also recaptured both the South Carolina and Georgia interior. Despite not winning a battle tactically, he was able to drive British field forces into the coastal city of Charleston and secure the two vital states of Georgia and South Carolina for the patriot cause.

A a member of the Battle of Eutaw Springs Chapter of the South Carolina Society Sons of the American Revolution (SCSSAR), I greatly enjoyed this history of the namesake battle of my SAR Chapter. Thank you.