By Allyn Vannoy

As the battalion officers surveyed the terrain before them, they must have been worried about the men who would have to cross it—the 300 yards of open ground to the banks of the Saar River lined with barbed-wire, concrete pillboxes, anti-vehicle “dragon’s teeth,” and reinforced with minefields in depth known as the Westwall or, more commonly, the “Siegfried Line.”

In March 1945, the Third Reich was under tremendous pressure as the Western Allies, having survived the Battle of the Bulge, were bulldozing toward Berlin.

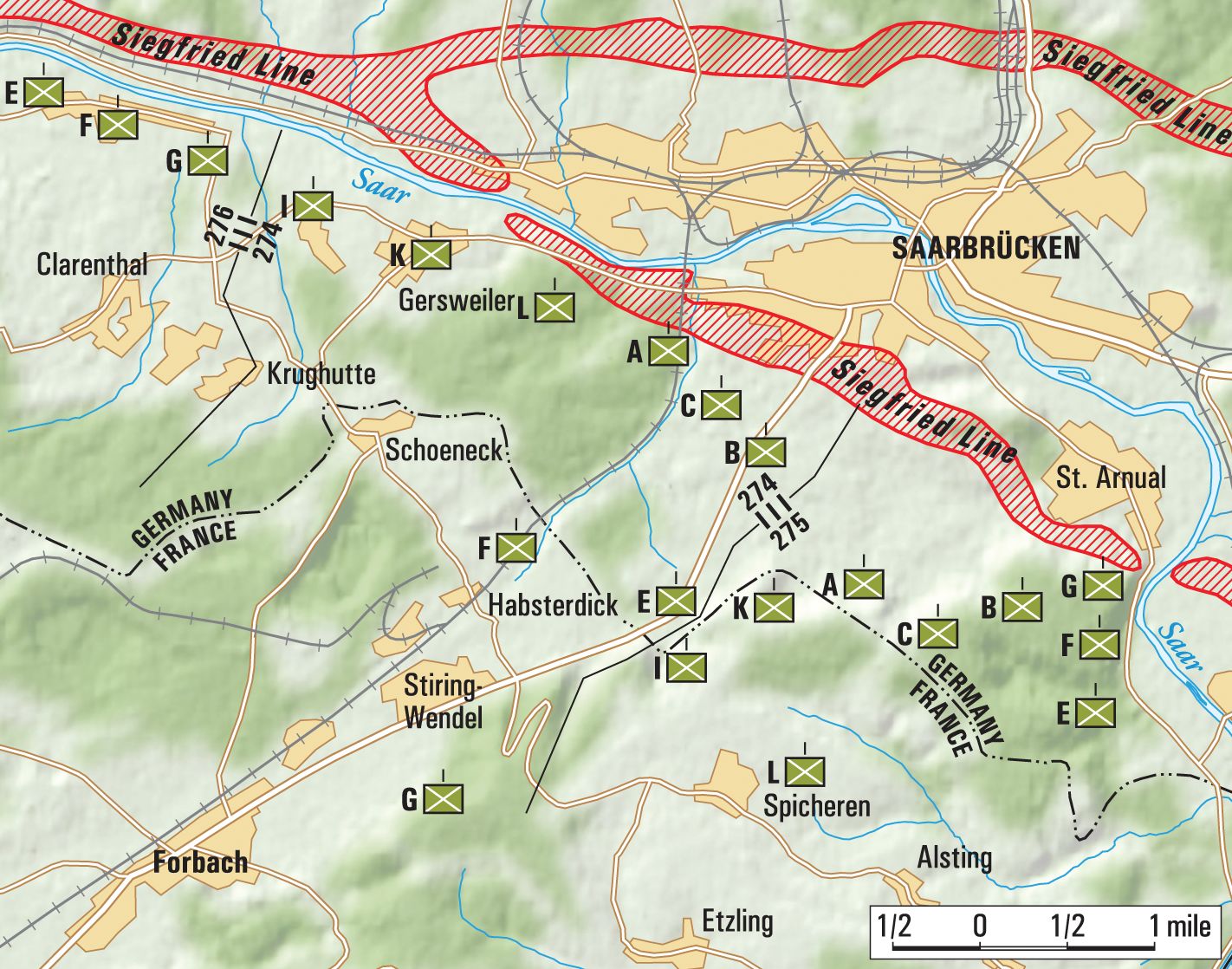

Moving across the northeast corner of France toward the Rhine River, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army was operating on the right (southern) flank of George Patton’s Third Army. The 70th Infantry Division, part of the Seventh Army’s XXI Corps, faced the Siegfried Line from Saarbrücken down to the Rhine River at Lauterbourg.

The Seventh Army’s Operation Undertone called for all three of its corps to move against the line. The main effort was to be made by XV Corps, in the center, at Zweibrücken, some 20 miles east of Saarbrücken. The XXI Corps, on the left, and VI Corps, on the right flank of Seventh Army, were to provide support. The 70th’s job was to exert pressure on Saarbrücken’s defenders, keeping them in place.

Formed in 1943 at Camp Adair, Oregon, the 70th Infantry Division adopted the nickname “Trailblazers,” with a shoulder patch showing an ax head over a mountain and an evergreen tree. The division had only arrived in the ETO in mid-December 1944, by way of Marseille, France; in January, it helped blunt the Germans’ Operation Nordwind in the Alsace-Lorraine region.

The villages south of the Saar River, to be assaulted by the 70th Division, represented the outer defenses of Germany’s fortified Westwall. The line, which had been started in 1936 by Nazi Germany’s Organisation Todt, the same engineering-construction group that had built the autobahns, stretched 390 miles—from Germany’s border with Holland to Switzerland. Hundreds of thousands of forced laborers worked on the line that Hitler was sure would be impregnable.

Saarbrücken, Germany, on the border with France, was the hub of the line along the 70th Division’s sector to the front. The 70th’s 274th Infantry Regiment, in the center of the division front, and the 276th Infantry, on the left flank, were to push the enemy back beyond the Saar, using direct fire to deal with pillboxes and bunkers, and then make an assault crossing.

High command pressed Major General Allison Barnett, the 70th’s commander, to attack without delay. Barnett passed the order to Colonel Samuel Conley, 274th Infantry commander, who in turn selected Lt. Col. Fred Cantrell’s 1st Battalion to lead the 274th in its attack. An advance beyond the Saar depended on cracking the Westwall and securing the highway to Metz as part of a strategic route into the Reich.

On March 9, Sergeant Patrick Barry, A Company, 274th Infantry Regiment, informed Sergeant Clyde W. Hill that their platoon had orders to move forward from the French town of Stiring-Wendel, about five miles southwest of Saarbrücken, until they made contact with the enemy; if they ran into a delaying force, they were to continue on until they had encountered enough to stop them.

Their platoon left Stiring-Wendel at 2 a.m. equipped with an SCR-300 radio—a backpack-mounted unit called a “walkie talkie”—with orders to contact company headquarters every 30 minutes. They moved past the Simon Mine, a large ore-processing complex, and advanced to the edge of the woods. When they radioed this information back to A Company headquarters, they were told that the regiment had issued orders for them to keep moving as fast as possible.

By this time Sergeant Hill and his platoon were well in front of the rest of the company. They advanced through woods, barbed-wire entanglements, and around abandoned German positions. They finally stopped at daybreak.

Once the rest of A Company had caught up, the platoons formed skirmish lines—3rd Platoon to the right, 1st on the left, with 2nd in support. The 3rd Platoon had advanced about 400 yards when its scouts spotted German troops on the distant banks of the Saar. The Americans dug in and kept their eyes on the enemy.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Platoon, B Company, had had orders to move to positions on the forward slope of the ridge just to the right of Stiring-Wendel overlooking the Metz Highway. They moved out at dusk in a squad column on the road leading into Stiring-Wendel, turned off on a curve, and proceeded out onto the ridge through the woods where they dug in.

While placing his men, Sergeant Edward Dunn told Privates James Moore and Vince DiFano to take a position in a former German trench. Moore jumped in the trench and landed on something soft. Moore told DiFano he thought it was a pile of trash. He felt around and caught hold of a foot, and then, seeing what it was, dropped it. He came bolting out, telling DiFano that they should move away as there was a dead soldier there.

Houses on the outskirts of Saarbrücken could be seen far off in front of B Company. Nearer to their right front, to the right of the town of Habsterdick, halfway between Saarbrücken and Stiring-Wendel, was a thick pine forest. Immediately in front of their positions ran the Metz Highway and about 800 yards across a flat open field lay Habsterdick, on the French-German border. Less than a mile to the southwest was Stiring-Wendel. Some distance away was a high railroad embankment. In the center of their position, a few yards to their front, was a small cemetery.

Habsterdick was situated atop a low hill. Just west of the town, running due north, was a deep valley bounded by high hills through which a small stream ran. To the north was the Saar River, Saarbrücken, and the pillboxes of the Siegfried Line. North of Habsterdick, was a large cement plant and quarry. Railroad tracks from Forbach and Stiring-Wendel, to the southwest, passed alongside the plant and then followed the stream bed up the narrow valley to the Saar. The valley appeared to be a natural approach route, causing the Germans to shell the area almost constantly.

Captain Edwin Mitchell, B Company commander, sent S/Sgt. James Broone, Jr., 2nd Platoon, to see the battalion commander, Colonel Cantrell, and be briefed about a planned raid into the German lines.

When Broone returned to the platoon, he informed the squad leaders that they were going to reconnoiter the terrain between the edge of the woods by the graveyard and the first few houses in Habsterdick. The plan was to occupy the first two houses and then launch an assault under cover of machine-gun and artillery fire. The orders were to complete the assault quickly, taking no prisoners.

Sergeants Broone and “Rhino” Luuko, along with Pfc. John Crozier, examined the terrain, but were not pleased about the company’s prospects. Broone notified Captain Mitchell and was told to await further instructions.

At 5 p.m., as the platoon waited and rested, replacements arrived. The veterans were shocked to see so much clean and complete equipment. The blankets were given special admiration.

B Company received word from battalion that there might be German tanks in Habsterdick, so it was decided to send a daylight patrol from the 1st Platoon to search the houses and barns. S/Sgt. Lloyd Horner, platoon sergeant, was to be in charge. Along with him were Sergeants Joseph Marshall and Robert Huttenhower, and eight privates equipped with an SCR-536 radio—a “handie talkie”—and a bazooka. They were to use their own judgment if they met any opposition—whether to fight or withdraw.

The patrol left at about noon and reached Habsterdick without any opposition. The patrol split into two groups and searched each block, followed by curious women and children. The civilians unlocked doors, let them into cellars, and allowed them to search their homes. They found no German troops.

Most of the civilians encountered said the Germans had left, and that they had been waiting for the Americans to arrive for almost four months. Many houses had been damaged by aerial and artillery bombardment. There was also a large Polish settlement there, with many of the men working in nearby mines.

B Company’s 2nd Platoon then arrived and together the two units moved out to clear the woods to the east of Habsterdick. After they had gone about 400 to 600 yards, they were ordered to dig in in the woods, right on the German border. No opposition had been encountered.

Each squad leader was told to send out a three-man patrol that night to maintain contact with the heavy machine guns that were located approximately 75 yards out on the right flank, and also to keep tabs on the woods that they had come through during the day. The 3rd Platoon arrived in Habsterdick about dusk.

At about 8 a.m. on March 14, Lieutenant Elmo Chappell’s 1st Platoon of B Company left Habsterdick and moved northeast toward Saarbrücken, crossed the German border, then over railroad tracks and a ridge, descended into a draw, and climbed a hill overlooking Saarbrücken.

Suddenly, intense machine-gun fire burst from a series of emplacements at the edge of Saarbrücken—the Siegfried Line. Visible were long rows of anti-vehicle, reinforced-concrete pyramids known as “dragon’s teeth” in front, backed up by a network of pillboxes with interlocking fields of fire.

Captain Edwin Mitchell’s B Company was chosen to spearhead the attack into the German defenses. He recalled. “It was sure suicide to cross the flat fields swept by perfect enemy fire, but orders were orders and we were going to try it.”

At about 9 a.m., B Company’s 1st Platoon passed through the 2nd Platoon. After 300 yards or so they halted, the 2nd Platoon coming up on their left. To their front was a wooded hill. On the left were some houses and behind the houses was a road and then a railroad track.

The 1st Squad was sent to clear the houses while the rest of the platoon waited. The squad was led by Pfc. Jack Hartwright, acting squad leader, along with 10 privates. They searched the houses, but found them empty. The men were ordered to move forward. The squad was sent along the banks of a brook, with a road to their left.

As they moved along the brook, Hartwright saw a German on a nearby hill. Hartwright fired at him, as did the others. Another German appeared from a bunker. As soon as they opened fire on this second man, German machine guns forced the GIs to take cover behind what trees were available.

Private Joseph Greco was hit and hollered for a medic, but the medics were held back by the murderous machine-gun fire. Private Harry Bargy managed to reach Greco and half-carried, half-dragged him back to where the medics were pinned down, but Greco died on the way.

Hartwright was also wounded and started calling for a medic. Bargy told him to crawl up to the road to where he could be helped across. Hartwright made it to the road, but was hit while crossing. Bargy ran to him, picked him up, and carried him down the road on his back, in spite of intense machine-gun fire. (Incredibly, Hartwright was later accused of having self-inflicted his wounds.)

Once he had delivered Hartwright to the medics, Bargy headed back to his squad. Atop the hill, Bargy saw Captain Mitchell and told him what had happened to the 1st Squad. Later, Bargy was hit by a sniper’s bullet that pierced the left side of his helmet, broke his left cheekbone, and lodged in his left shoulder.

In the meantime, Private Daniel Devitt, having taken cover behind a tree, was trying to convince Private James Gurley, who had been hit in the shoulder, that he needed to get back to the medics. When this proved unsuccessful, he told Gurley that he was going for help. Devitt found a medic, but he was involved in dressing Hartwright’s wounds.

In the quiet after a mortar barrage, Hartwright was taken to litter bearers who carried him back to the battalion aid station. Devitt then discovered he had a bullet hole through the sleeve of his own jacket and another through his helmet.

While the 1st Squad had been engaged, the 2nd Squad reached its objective on the left of the 3rd Platoon and saw Germans on the hill to their front. When they and the 1st Squad began firing, they also received intense machine-gun fire in return.

Four Germans were caught in the open and raised their hands to surrender. They started walking towards the Americans when Private Virgil Sherburn, a BAR man, either frightened or over-exuberant, shot at them. He missed as the would-be targets ran under the crest of the hill and disappeared. Rifle grenades were then fired at the far hillside. The 2nd Platoon then dug in at the top of the hill.

B Company’s 3rd Platoon had moved out at 8 a.m. with two squads forward and one following, accompanied by Captain Mitchell. When they reached the railroad track that ran towards Saarbrücken, they stopped for about an hour while Mitchell attempted to make contact with the forward platoons.

Mitchell ordered Sergeant Dunn to make contact with either the 1st or 2nd Platoon and find out if they had met any opposition, but he wasn’t certain of the position of either. Dunn took three privates with him as he headed out. They went about three quarters of a mile before they found the 2nd Platoon digging in. Dunn notified Captain Mitchell.

The 3rd Platoon moved forward again. After a short while, they contacted the rear of the 1st Platoon. When they reached an open field, they skirted it to the right. They went down into a small draw and joined the 1st Platoon on a dirt road leading onto a bare hill overlooking Saarbrücken. The forward elements of the 1st Platoon had been stopped by machine-gun fire from Siegfried Line pillboxes.

Late in the afternoon, the 3rd Platoon, with the 1st Platoon in the woods to their left, moved back into a long winding trench that the Germans had vacated. The 1st and 3rd Platoons’ CPs were in a house about 50 yards behind the trench. Heavy machine guns were set up behind the 3rd Platoon positions covering the right flank. Another section of heavy machine guns, along with the light machine gun and mortar sections, were placed with the 2nd Platoon.

While B Company had been advancing during the day, C Company had also been in motion. On the night of March 13-14, C Company was told that they would be moving to Stiring-Wendel to aid A Company in its attack.

In the morning, the members of the 4th Platoon, C Company, not on duty, finished ridding themselves of German ammunition and other equipment they had collected. Several men had found bicycles they used to carry the bulk of their items—loaded like packhorses. A detail also dug a grave for the bodies of two German soldiers and then was assigned to bury a horse that had been killed by shrapnel and was giving off a strong odor.

At about 7 p.m., K Company, 275th, arrived to relieve C Company, the company pulling out at 9 p.m. As they moved along the road towards Stiring-Wendel, the members of the 1st Platoon could hear the distinctive boom of 4.2-inch mortars rapidly firing from the hill behind them. The troops suspected that something big was coming.

The 3rd Platoon led the move into Stiring-Wendel, taking up positions at the edge of the town at about 10 p.m. The company paused while further movement was being worked out—determining how to deal with anti-tank ditches and possible mine fields. After an hour, they were told to fall in and prepare to move out. Those with bicycles were told to leave them behind. For the next three hours they climbed up and down railway and anti-tank embankments, following A Company. At 3 a.m., exhausted, they came to a halt.

On the morning of March 14, D Company’s mortar platoon arrived at Habsterdick and immediately set up its tubes in accordance with company commander Lieutenant Ernest Rokahr’s orders. Emplacements were dug in the yards and gardens between the houses where the platoon had established billets.

Sergeant Anthony Study and Pfc. Lawrence Grinwald returned to the platoon after spending 10 days assigned to OP duty. Study appeared to have difficulty moving about, having a bad case of the “GIs.” The 1st Squad saw to it that he had clean facilities and then put him to bed—the sergeant refusing to go to the medics. The members of his squad tried to keep him in bed to rest up, but—such was his dedication—every time he heard the mortars in action he would come out to lend a hand.

Most of the city of Saarbrücken was north of the Saar, the river running east through the city, then looping southeast to the town of St. Arnual, with the Siegfried Line running northwest to southeast along the city boundary.

To the men committed to the attack on the Siegfried Line, it looked much more formidable on the ground than it had on paper—it appeared impregnable.

In front of the 274th was open ground, about 300 yards to be crossed, to the steep southern bank of the Saar. The northern bank, also steep, was lined with a double-wire barrier, backed by bunkers with interlocking fields of fire covering every foot of ground. Concrete machine gun nests, flush to the ground, were set along the riverbank. Mine fields reinforced the defenses.

On the morning of March 15, the 3rd Platoon, A Company, reached Schoeneck, just west of Habsterdick, then moved north to the village of Gersweiler, overlooking the Saar and the German defenses. The GIs dug in, reinforcing their positions with sandbags and logs.

One of the light machine guns of the Weapons Platoon, B Company, was placed near the 2nd Platoon CP. On its left was a blind spot created by a high rock wall. The machine-gun squad consisted of a crew of six. In the early morning hours, in the pitch dark, two crewmembers had just come off guard. They woke up two others and then went over to the 2nd Platoon CP for a smoke. In the meantime, a German patrol slipped through B Company’s perimeter, quietly capturing the gun crew along with the two sleeping men.

At dawn, there was such a heavy smokescreen that it was possible to see only a few feet. At first the men of B Company thought it was fog and then thought it was a German smokescreen laid down in preparation for an attack. Captain Mitchell gave orders to hold positions at all costs. Later it was learned that the smoke had been laid down by American artillery or 4.2-inch mortars, and that C Company was to attack across the open field to their left. But the attack did not materialize.

Around 6 a.m., members of the 2nd Platoon, B Company, heard firing along their left flank. Sergeant Luuko, leader of the 3rd Squad, was told by Sergeant Broone that the Germans were counterattacking; however, he couldn’t see any Germans. The firing was spasmodic, though at times very heavy.

Pfc. Henry Zampier, D Company, recalled: “Early in the morning, we heard shouts of ‘Counterattack!’ We took shelter behind a shed as cover against the flat-trajectory fire just as the enemy started dropping smoke shells. We started sending fire orders and digging ourselves a hole at the same time. Soon the 88s began dropping all around us.

“Our radio, which was the only means of communications that we or the rifle platoon had, was knocked down [out] twice . . . We fired the mortars by sound as we were not able to observe because of the smoke and dust and the fire being laid down by the Germans. However, we figured we were doing plenty of damage as the guns were well zeroed in and were firing only about 25 yards ahead of our own positions.”

The light machine gun near Sergeant Luuko’s position fired into the woods to their right front; the Germans responded with heavy fire. Sergeant Broone called for a 60mm and 81mm mortar barrage into the area that the Germans would have to cross to reach the American positions. The barrage gave the area a heavy pounding.

German artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire continued intermittently all day while sniper fire harassed and caused casualties. Privates John Blair, Broadus Bunce, and Ronald Althausen were together in a foxhole. Bunce was hit during the morning in the right shoulder by sniper fire; he was evacuated. Later, Blair was shot in the head, probably by the same sniper, but it only knocked him out. A medic was not able to reach Blair for a half hour.

As the medic started to lift Blair out of his foxhole, the sniper killed the medic instantly with a bullet through the head, the bullet striking the red cross on his helmet. Since it was now impossible for a litter team to get to Blair, Private Althausen stayed with him until after dark when a litter team arrived and carried him out; however, Blair died later.

When orders were received that B Company was to attack the Siegfried Line, Captain Mitchell called the platoon leaders together to discuss plans and review aerial photos and topographic maps. It was decided to make a frontal approach to the German positions rather than moving to the left; German positions on the left were well fortified and strongly defended. Also, the Germans might not expect an attack to come right over the bare hill before them. The attack was to be preceded by an intense artillery barrage.

According to intelligence from prisoners, each pillbox was manned by at least 17 men, mostly ex-Luftwaffe personnel, each with enough food to last two weeks, and there were trip-flares and mines in front of the pillboxes. It was also reported that the American artillery had not had much effect on the pillboxes.

Plans called for the 3rd Platoon to jump off at 3:15 p.m. following an artillery barrage. But then it was decided to fire an additional barrage, and so it was almost 4 o’clock before the platoon moved out. As they advanced, Lieutenant Chappell brought his 1st Platoon into position behind the 3rd along a reverse slope.

The 3rd Platoon moved out with two squads forward and one back. The 1st Squad was on the left, the 2nd Squad, under Sergeant Penland, was about 75 yards to its right; the 3rd was to the rear under Sergeant David Mann. S/Sgt. Robert Rysso was with the 1st Squad, carrying an SCR-536 radio, maintaining contact with company headquarters.

While the 1st Platoon was waiting on the slope of the hill, the Germans laid down artillery fire; however, most of it landed off target, causing no injuries. As they moved out, Sergeant Rysso sent Private Lawrence Condict, scout of the 1st Squad, over the crest of the hill. He came back and reported that he thought it was going to be rough going.

With the 1st Squad providing a base of fire, both squads started moving up towards the brow of the hill. Sergeant Penland and Dunn were trying to get scouts out, so Pfc. Luther Hanson was told to move out fast so that they would reach the brow well before the rest of the squad.

Private Nicokoris reached the top and started down the other side. Pfc. Gordon Pean, from his position, could see the dragon’s teeth, dug-outs, and trenches of the Siegfried Line. He wondered why it was so quiet and why they were being allowed to walk over the top of the hill and into the open.

Most of 1st and 2nd Squads had reached the brow of the hill and passed over to where the ground leveled out when all hell broke loose.

Nicokoris hit the ground, then got up and ran back a short distance but was knocked flat. Not knowing the extent of his injuries, Nicokoris’s buddies told him to lie perfectly still. Dunn, the squad leader, reached the wounded man and saw he had been hit in the right side of the chest.

In an exposed position, Dunn and Nicokoris started to crawl to the rear but another bullet hit Nicokoris, this time in the left upper chest as he tried crossing a fence. Dunn told him to stay down as American tanks were on the way. The rest of the squad had gone to ground, using any depression for cover.

On the left, as the 1st Squad came under fire, the squad leader, Pfc. David Traum, went out to check on Condict, the scout, who was pinned down. Traum came back and also reported to Sergeant Rysso the location of the German machine guns. Rysso called back and had artillery laid in on them. As Traum went back for Condict, he was hit in the foot by a machine-gun bullet, but managed to crawl back about 50 yards to a large shell hole that was half full of water.

Meanwhile, a medic and Private Sigsbee Newton were called forward. Newton was new to the unit—this was his first action, and he had volunteered to assist the medics. Although scared, he remained in the fight, doing all he could for the wounded.

While tanks were coming up, Private L.T. Ingraham, who had taken over the 1st Squad after Trauma was wounded, was himself hit in the shoulder and collarbone by machine-gun fire. Meanwhile, Nicokoris was hit again, this time by shrapnel, in the back and legs.

When the tanks appeared, several men made an effort to get behind and use them for cover. Private Maurice Palmer, Pfc. Howard Frazier, and another man were running towards a tank when a shell burst nearby, hitting all three. Frazier was dazed for a minute, then discovered that he had been hit in the hand and right shoulder, but was able to make his way back to an aid station where he found he also had a machine-gun bullet in his leg.

Pfc. Pean saw Palmer lying in the open and told him to get behind the tank. Palmer said he couldn’t, that he was hit and needed to be assisted.

Additional casualties included Condict, who was hit in the thigh by shrapnel, Pfc. George Rakowski, who was hit in the arm, Private Francis Casto received a broken leg, and Private Norbert Jannink, a bazooka man, was hit in the head and face.

After 15 minutes, the two tanks providing support decided to withdraw. The crews claimed that the ground was so soft that they could not cross the obstacles before them. As the tanks started back, the remaining infantrymen were ordered to withdraw; artillery provided a covering barrage.

Several of the riflemen and a medic went out onto the hilltop to help bring in the wounded. Although in the open, they drew no fire. They found Palmer dead, Jannink unconscious.

Sergeants Rysso, Penland, Dunn, Mann, and Private Newton took cover in a shell hole. Penland recalled what happened next: “Two artillery shells whistled across the top of the hole, coming from behind our lines and almost knocking me flat. They landed in the general vicinity of our wounded out on the field. I called back to Sergent Rysso to have the fire lifted because it appeared to be landing among our wounded men.

“I was on the forward slope of the crater near the top, trying to see where the shells were landing. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see, coming from my left, two men supporting another, coming towards the shell hole. I glanced around and recognized [Pfc. Charles] Andrews on the right, supporting a wounded man and [Pfc. John] Helaszek to the left. I did not have time to recognize the third man who I was told later was [Private Fred] Ledford.

“I just got out the first word of ‘Get down!’ when a large-caliber shell made a direct hit on the three men who were at that time approximately six yards from the hole. I saw a tremendous flash of fire and black smoke and pieces of the men’s bodies flying through the air.

“The concussion from the shell blew my steel helmet off and threw me into the bottom of the crater, which was filled with water and mud. One man’s body flew over me and hit the water beside me. One of the men’s legs hit on the right of me in the water. The medic, who was on the near side of the crater, was rolling down the side. I threw out my hand and stopped him before he rolled into the water. He was covered with blood from the men who had been hit by the shell. I asked him if he was hit and he said he didn’t know.

“He crawled over to help another man who was pushing himself toward the water with only his legs. This was probably Ledford who was later found dead in the hole. I looked around and saw a man’s chest and hands sticking out of the water. I grabbed him to pull him out, thinking that possibly he was still alive and would drown. I saw that he was mangled and dead and let him slip back into the water.”

When Penland was able to withdraw back to where the rest of the platoon was, he could only find 10 uninjured men—the 3rd Platoon’s casualties were four killed and 17 wounded. Those left took up positions to meet a possible counterattack, which failed to materialize.

After the 3rd Platoon returned from the day’s action, the 1st Platoon moved up and took positions to the left of the 3rd, with the 2nd to its right.

Lieutenant (later Captain) Charles Blanchard, C Company CO, had assembled his company near Stiring-Wendel and set out at 9 a.m., following a route that A Company had taken during the night up toward the high ground overlooking Saarbrücken. The company advanced over a mile, moving through Habsterdick, until it reached the cement plant and quarry. There, Blanchard halted the company and held a council of war.

The advance then resumed with Blanchard’s C Company entering a wooded area and spreading out, then making contact with the 2nd Platoon. While moving through the woods, the 3rd and 2nd Squads drew fire.

Lieutenant Robert Connor ordered assistant squad leader Pfc. John Poveliatis to take three men and check the situation ahead of them. As Poveliatis moved towards the left, where Pfc. Frank Travis, 2nd Squad scout, was located, machine-gun and sniper fire pinned them down. The GIs responded with their own fire, but this was ineffective as the Germans could not be spotted.

It appeared that the fire was coming from a hillside some distance away, directly in the line of advance. The 2nd Squad was able to finally advance in short rushes, but had to halt at the edge of the woods when they reached a wide ravine. Beyond they could see the dragon’s teeth of the Siegfried Line.

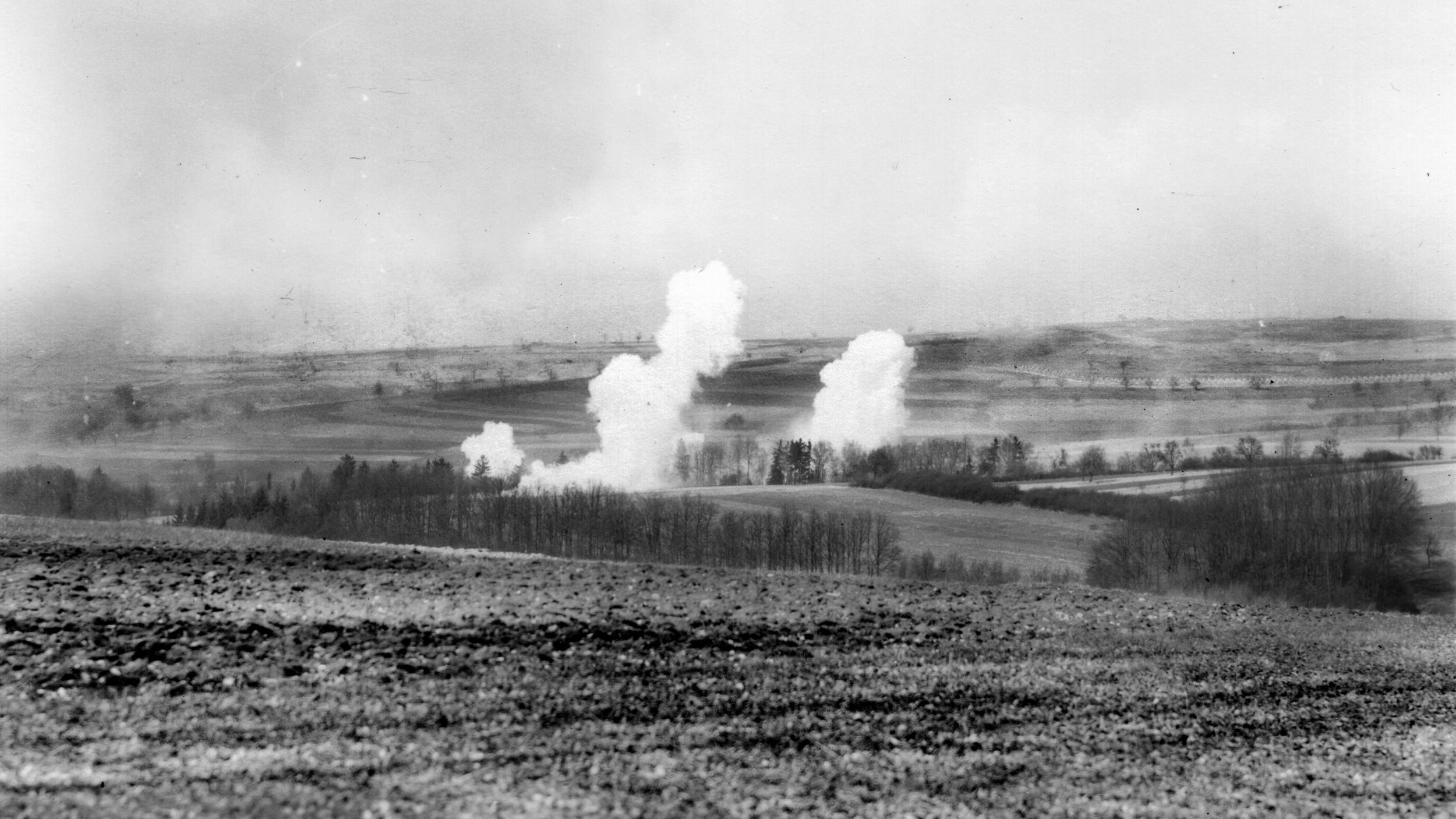

With the rifle platoons pinned down, mortar fire was called down to knock out a couple of machine-gun nests. Sergeant Leon Bartram selected positions for his mortars, ran wire to a forward OP, and then directed fire. About this same time American artillery opened up with a heavy concentration that saturated enemy positions.

The Germans were seen to be running from their trenches and foxholes to the protection of the Siegfried Line pillboxes, but the platoon’s 60mm mortars were able to pick them off as they ran. Despite being wounded in the right hand, Sergeant Bartram continued to direct fire. He was later evacuated to the battalion aid station.

Later, the word was given for C Company to move to the right of B Company with A Company to move in and replace C.

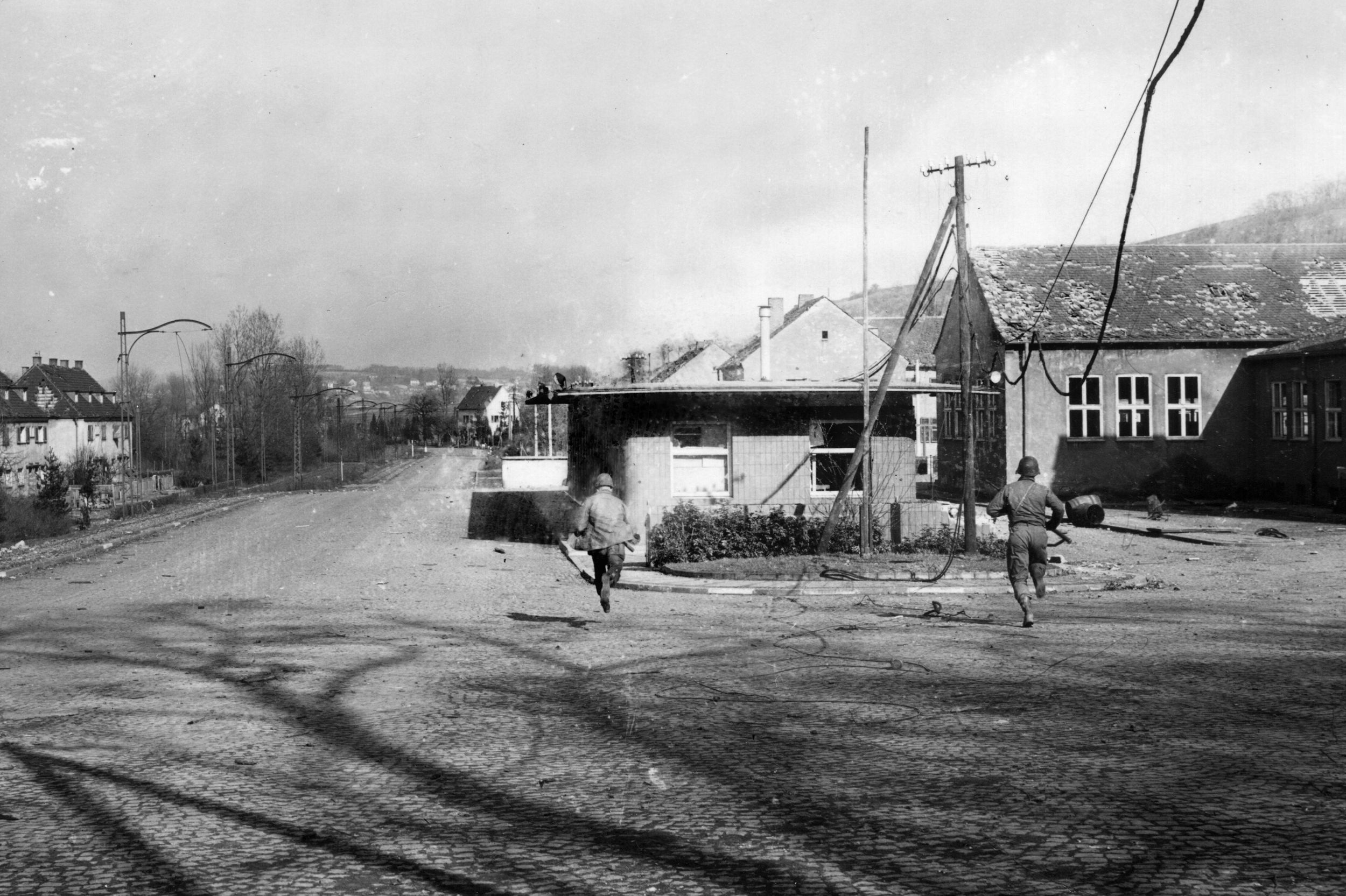

As the men maneuvered, German machine guns opened up again, causing the GIs to dash for the cover of a wooded ravine. Emerging, they were forced to scamper across railroad tracks while exposed to enemy fire, jump down from a high wall, and then cross a highway, taking cover in what was formerly a zoo and park.

They found the buildings had been badly damaged, so they sheltered along the side of a hill behind the remains of the structures. Although subjected to a severe shelling, they were protected there and afterwards received the first hot chow they’d been given in days—providing a boost to morale.

The night passed uneventfully, although several contact patrols were sent out. Tech/5 Edwin Pressler, 2nd Platoon, B Company, had his BAR ready for action, should it be needed, covering the front. “The presence of that worthy weapon always gave a fellow a good feeling of security,” he said.

Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, Seventh Army commander, arrived at 70th Division headquarters on March 16 to press Barnett to get his attack underway. Barnett argued that an immediate attack would cost needless casualties. Also, Third Army’s advance to the rear of Saarbrücken would cut-off the Germans, thus negating the need for a frontal assault. Patch nodded and agreed to a delay.

That morning, a replacement officer, Lieutenant Marcil, arrived and was attached to the 1st Platoon, B Company, where he spent most of the day asking questions and looking over the company’s positions. He and Lieutenant Chappell went to the 2nd Platoon’s previous positions to check on a report that a private first class named Harold Davis had been found alive and evacuated. Instead, they found Davis’ body.

They also discovered that C Company had not taken over the positions to which they had been assigned, and that there was a gap in the American lines. Chappell notified battalion headquarters, which directed C Company to move and fill the gap.

During the morning, Chappell went out to the shell crater where the 3rd Platoon men had been hit the day before and identified Pfc. Helaszek’s body by his dog tags. While he was in the hole, he heard the crack of a bullet as it hit the ground just outside the hole.

At first he didn’t recognize what had happened, then realized it was a sniper’s bullet. He tried to see where the sniper was as another bullet came in. As he dashed to get his carbine, which he had left outside the hole, a third round struck nearby.

Chappell noted a water tower to his right and calculated from the angle the shots that the sniper must be there. He then made a break back to his lines and warned others. As soon as he got back to his CP, he showed the artillery forward observer where he thought the sniper was. They fired a few rounds and, once they had it zeroed in, they added time-fire. After a few more rounds, the sniper and water tower were eliminated.

During the morning, Blanchard’s C Company moved out, prepared to bypass A Company on its right flank; however, orders were changed at the last minute, so they moved to the left and rear of A Company. The 1st Platoon led the company, followed by the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th.

When they had just reached the nose of the hill they were assigned, Siegfried Line machine guns opened up, hitting three 1st Platoon men. Unable to advance, the platoon dug in while the other platoons moved into position on the left, behind A Company.

In the meantime, tanks returned, moving into position to where they could fire on the Siegfried Line pillboxes, and C Company was ordered to pull back and move to relieve B Company. As C Company moved into the vacated foxholes, they found that B Company had departed in such haste that they left behind several wounded and dead comrades.

The men of B Company spent the 17th, a warm and sunny day, cleaning weapons and reinforcing their foxholes—deepening them and adding a covering of boards or logs with dirt over it for protection against air bursts.

Lieutenant Chappell, 1st Platoon, visited the Company CP to see Captain Mitchell. While he was there, a call came in saying that the sound power system between the 1st and Weapons Platoons would be used to adjust artillery fire, but the sound power equipment had to be moved from the cellar of a house to an upper story.

S/Sgt. Horner and a medic were handing it from the top of the cellar steps through the kitchen window to Lieutenant Marcil and an artillery observer when a shell screamed in and hit the side of the house, killing the lieutenant and the observer. Horner and the aid man were badly hurt as well; Horner later lost his leg. It had only been Marcil’s second day on the line.

The day of an infantryman was one of move, dig in, move again, and dig in again—this was how one survived. A foxhole or dugout was never complete, never deep enough, never comfortable enough.

The 2nd Platoon, B Company, was engaged in such activity when orders came to move about 200 yards to a new position and dig in again. A line of defenses was established covering the strip of woods from the left flank to the open field on the right flank while the 3rd Squad established outposts. The line was reinforced with a section of light machine guns. Lieutenant Connor located his CP a few yards behind the 2nd Squad. The platoon was delighted to see members of the CP group digging in as well.

During the morning, the 3rd Platoon, C Company, pulled back about 300 yards while artillery pounded German positions, but with little apparent damage. About 5 p.m., they moved back up to their previous positions.

The action picked up. In C Company’s 4th Platoon sector, heavy sniper fire had wounded nine riflemen and two medics; any movement in the area seemed to draw fire. The snipers were too close to the company’s positions for the use of artillery, so 60mm mortars were employed. The mortars had only fired a few rounds when a German “88” round landed close to the mortars, wounding three men—Pfc. Warren E. Culp, Pfc. Harry D. Brown, and Sergeant Leon F. Below—and knocking one mortar out of action.

At about 2:30 p.m. on March 18, Pfcs Gerald Luther and Winifred Bollinger, Weapons Platoon, were reading comics near their foxholes. A mortar round came in behind them and another to their front. Bollinger stayed where he was, but Luther took off for his hole. He was wounded just as he reached the hole while Bollinger was untouched; Luther returned to his unit in April.

In the 4th Platoon’s area, an occasional German mortar or artillery round fell. There was one incident that members of the company considered a near miracle. Sergeant Glen Main was standing about five feet from his foxhole when a mortar round landed within three yards of him, blowing him several feet into the air, and landing him in his hole, virtually unhurt. However, his rifle was riddled with holes.

During the day, elements of Patton’s Third Army reached a point 60 miles northeast of Saarbrücken; Intelligence reported German forces withdrawing towards the Rhine. But the German defenders in front of the 70th Division continued to resist. American patrols, attempting to cross the Saar by boat, encountered withering fire.

The division was again ordered to attack across the Saar the next day, March 19. The 274th was to take over the 276th’s positions and prepare to attack Saarbrücken’s defenses south of the river, then cross the Saar at the Metz Highway bridgehead. General Barnett cautioned his commanders to minimize casualties. H-hour was to be determined by the situation at hand, and all units were to be prepared to move on an hours’ notice.

Around daylight, all direct-fire weapons—anti-tank guns and tank destroyers—opened up with a furious barrage in an effort to reduce the river-front defenses. The cannonade appeared to be effective against the pillboxes while other guns targeted factories and possible enemy OPs.

C Company relieved B Company and crossed the road on their left, climbed a hill, turned left, and followed railroad tracks until they branched off. Here, they went to the right and then turned into the woods, advancing until they reached another railroad track on a high embankment. They proceeded and finally reached a road in the vicinity of Schoeneck, north of Stiring-Wendel. The terrain was heavily wooded and hilly.

Lieutenant Harold Dunbar, 1st Battalion S-2, had sent word that it was believed that the Germans had abandoned the pillboxes to their front, and that heavy German artillery and mortar fire falling on the battalion’s positions was probably covering a withdrawal. Lieutenant Blanchard, therefore, decided to send out a patrol to see if the German pillboxes were still occupied.

The patrol, led by Tech/5 Willie Prejean of the 2nd Platoon, returned shortly after 6 a.m. They had checked six pillboxes and found all of them abandoned. Once the information was transmitted to battalion, the company was ordered to move forward, pass through the Germans’ fortified positions, and occupy the high ground just over the Saar.

At about 8 a.m., the company moved out. Advancing in columns of platoons and checking pillboxes and bunkers as they went, they passed through the Siegfried Line without incident, then wheeled left onto high ground. Five prisoners were taken by the 3rd Platoon as they came forward, one of them volunteering to lead the way through booby-trapped and mined areas. Positions were occupied without losses.

Lieutenant Blanchard was informed by Colonel Cantrell that C Company was to cross the river and fan out, securing the bridgehead while those units that had crossed earlier pursued the enemy. However, word was then received that they were to pull back and that the 275th would relieve them. Their battalion was to be the last battalion of the division to cross the Saar.

Shortly after noon, Blanchard and his men moved back to the company supply point, drew rations, and were told to wait for trucks that were to carry them forward. When no trucks appeared after a couple of hours, they started walking. While heading down the road, the trucks arrived to collect them, transporting them across the Saar.

As they passed through Saarbrücken, they found that the center of the city had been pulverized during the fighting. Streets were unrecognizable as such. There were not even skeletons of buildings—just acres of wreckage and large heaps of rubble.

The men of the 274th Infantry were nearing the end of their journey across France and into Germany. Mopping-up operations were to follow, the division performing occupation duties in the Saar Basin area and then finding itself in the vicinity of Frankfurt, Germany, when hostilities ended in May 1945. They had compiled 86 days in combat and suffered 3,919 men killed, wounded, missing or captured during that period of time.

In October 1945, the Trailblazers returned to the U.S. and were deactivated at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, proud of the fact that they had performed with honor in its assignment to breach the Siegfried Line and break the dragon’s teeth.

The author, a frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly, resides in Hillsboro, Oregon. He is the author of Against the Panzers: United States Infantry versus German Tanks, 1944-1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments