By William McPeak

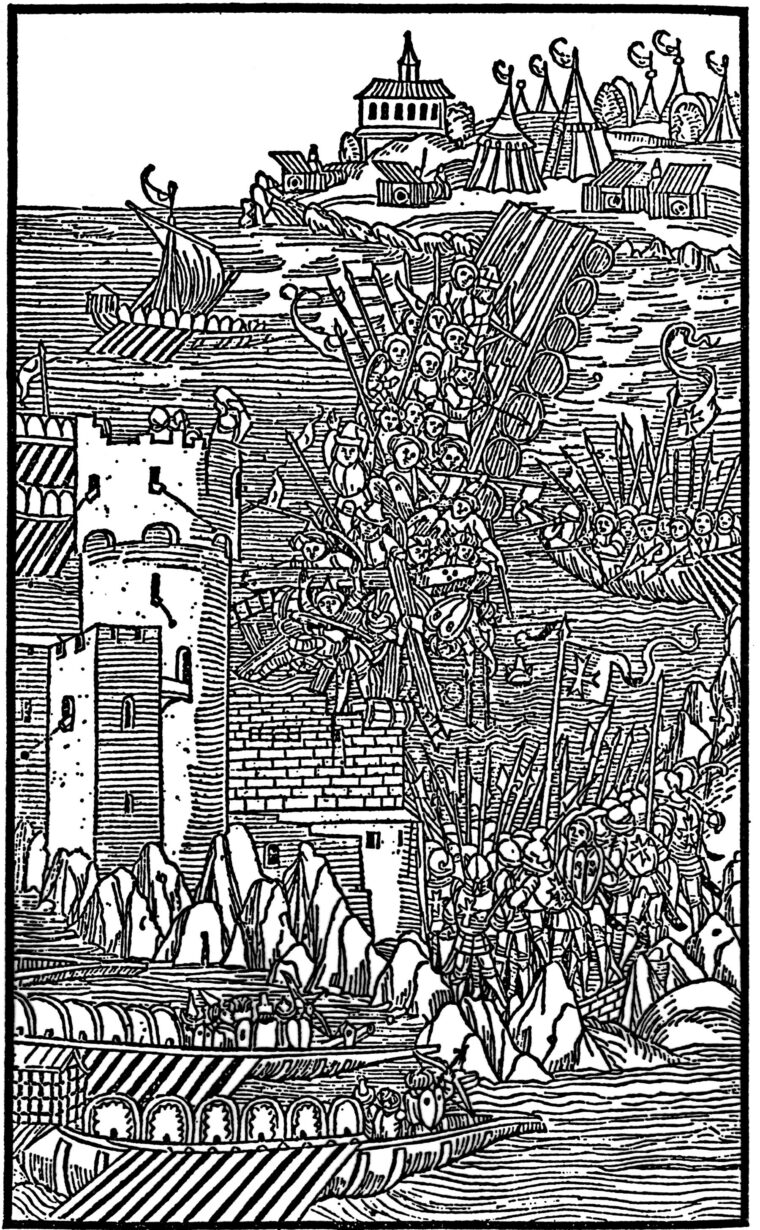

Although the great Crusades were over by 1309 ad, one old crusading order continued to evolve, flourish, and make enemies—the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem. The Turkish domination of Asia Minor had passed from the Seljuks to the Ottoman Turks by the late 13th century, and with it came renewed and relentless harassment of the Knights until they were forced from their longstanding mainland base at Acre in 1291. The Knights reorganized, moved temporarily to the island of Cyprus, and in 1309 boldly seized the Turkish-held island of Rhodes as their new permanent base. For the next two centuries they would find themselves on a collision course with the mighty Ottoman Empire.

Although the Knights Hospitallers was originally formed as a nursing order for pilgrims to the Holy Lands, a military arm was added in 1130 for self-protection and it developed into a highly efficient force. While the other two major crusading and nursing orders, the Knights Templar and the Teutonic Knights, declined amid internecine political struggles, the more pious and prosperous Hospitallers became a bulwark in the East for European interests. Basic survival was the impetus for the order’s most important change: its improved military technology and efficiency. The order needed such martial traits to maintain an edge against the vast numerical superiority of their Muslim foes. Both traits took a huge leap forward when the order seized Rhodes, at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. With an island base, the Knights quickly saw the potential for a much larger sphere of influence. Their strategy and tactics now focused on integrating marine warfare with their legendary battle readiness.

The Unshakable Faith of Religious Knights

Even more than their military technology and efficiency, the key to the Knights’ success was an unshakable psychological resolve built on stalwart religious faith and an elitist esprit de corps. These were so-called “nursing priests” who did not marry and had to obey strict monastic rules—although those rules suffered much stretching. The “Brother Knights” were a caste of European nobles who had worked their way up to a final level of knighthood known as the “Grand Cross,” which permitted them to wear the order’s white eight-pointed Maltese Cross on a red surcoat. The Grand Master was the elected leader of the order, chosen from the upper echelon of experienced Knights. Below him were various officers who formed the order’s highly structured pecking order. Commoners of good background were allowed to join the order as “brother sergeants” or “servants-at-arms.” Both groups underwent five years of intense weapons training. Knights were also expected to be experts in fortification, siegecraft, and ordnance.

Gunpowder technology was in the forefront of the order’s innovative approach to weaponry. Artillery was already an important defensive mainstay, and in the mid-15th century the order shifted its emphasis from the crossbow to the new shoulder-aimed firearm, the arquebus. This represented a radical departure from the stance of contemporary European nobles, who considered firearms beneath them—the chosen weapons of knaves. But just as European nobility had come to accept the cannon, they would eventually accept personal firearms as well. For the Knights, such acceptance was a necessity. Equipped with a state-of-the-art fleet of galleys oared for high maneuverability and mounted with small cannon, the Knights protected Christian pilgrims and commerce, while the order’s regular raiding parties, called “caravans,” were dedicated to disrupting Muslim interests in the eastern Mediterranean. To further keep the Turks off balance, the Knights perennially changed alliances with Ottoman border antagonists: Persians to the east and Egyptian Mamelukes to the west.

With the final storm and sack of Constantinople in 1453 by Sultan Mohammed II, the fall of the Byzantine Empire opened the way for new land-grabbing objectives in Eastern Europe, particularly on the Greek peninsula. Meanwhile, the order played their usual game with Turkish rivals, plotting frequently with Persia. These dealings soon put Rhodes next on the sultan’s list of military priorities. Former attempts to capture Rhodes had failed repeatedly in the 14th century. Egyptian Mamelukes made several attempts on Rhodes in the next century, in 1440, 1444, 1457, and 1469. So far, the order had held Rhodes safely from all challengers and kept their ascendancy at sea, bedeviling Muslim shipping with impunity. But by 1480, Mohammed II was prepared to finally make the order—those “sons of Error and allies of Sheiten”—pay for its crimes against Allah.

The order’s fame had lulled Europe into a complacent belief that the Knights were virtually invulnerable and could take care of themselves. But the relatively small size of the order meant that guerrilla warfare was their chief sock-in-trade, not pitched battles. Through concerted defensive tactics, they had continually disappointed those who thought they could take Rhodes by siege. Still, the order could not be sure of victory if a concerted, massive assault was made upon them by the full forces of Islam. They would need to augment their numbers with European volunteers. That was the problem—Rhodes was relatively isolated in the far eastern Mediterranean, and the Turks were sure to set up some sort of blockade. Reinforcing the stronghold on short notice would be exceedingly difficult, particularly considering the time it took to prepare and mount a military force in the late 15th century.

Rhodes Erected a 150-Foot-High Tower and a 24-Foot-Thick Wall

After the fall of Constantinople, the order kept busy refortifying Rhodes’ defenses under the direction of four succeeding Grand Masters. An essential object of refortification at Rhodes was the great galley and commercial harbors on the east coast in front of the city. The 150-foot-high Tower of Naillac had been erected in 1421, providing a means of drawing a chain across the entrance to the commercial port, called the Mandraccio. By 1467, after nearly four years of construction, an impressive round, fortified tower with 24-foot-thick walls had been erected at the end of a new mole, or breakwater, that arched out from the south end of the galley harbor.

The crescent-shaped main harbor and the galley harbor were protected by shore batteries on the seaward wall of the city. At the end of a second and older mole at the southern end of the harbor was the fortress of St. Angelo, also known as the Tower of the Windmills because three of the structures had been erected alongside the mole to service grain ships. In all, some 30 castles and fortified points were built or refurbished on the island, which was ringed by a system of shoreward watchtowers. For communications there were simple semaphore techniques; carrier pigeons and signal fires were used for early warnings to the order’s main keep or castle complex, called the Convent. Rhodes had no less than seven well-fortified gates.

Throughout the 1470s, Grand Master Pierre D’Aubusson had ascended to the top position. An expert in fortifications, he was just the sort of leader the order needed—an inspiring commander who had never known defeat. As he temporized with the Sultan’s renegade Greek envoys in 1476, D’Aubusson put in enough supplies for two years of siege, reinforced all the islands in the Rhodes chain, and sent out a call for former members to return along with new European volunteers. Meanwhile, a group of Ottoman military leaders and European renegades in Constantinople continued pestering the sultan to make good his promise to wipe out the “terrible monks” on Rhodes. While the sultan seemed to hesitate over committing himself to force the situation—his terms with the order called for nominal tribute in return for nonmolestation of his commercial shipping—D’Aubusson continued his preparations.

70,000 Strong: The Turkish Invasion Army

By the winter of 1479, the Turkish campaign was already in motion. Spies and double agents were active on both sides. A Greek renegade, a so-called prince of the imperial house of Palaeo-logus named Misac Pasha, led a reconnaissance squadron of Turkish galleys to Rhodes that winter. D’Aubusson had received reports of his movements and was ready and waiting when Misac disembarked his cavalry for a raid on the Knights’ stronghold. Getting onto the island was easier than getting off it. Misac’s horsemen found their escape route blocked at every turn and suffered heavy losses.

Meanwhile, back in Constantinople, a Turkish invasion army—some 70,000 men, horses, mules, supplies and munitions was gathering. Taking a page from the Knights’ book, the sultan made sure there were many arquebuses as well. The Turks marched overland from the Hellespont to the port of Physcos on the Asia Minor coast, only 18 miles from Rhodes. A siege train of cannon and other heavy equipment arrived by sail. All the while, D’Aubusson was kept appraised of every feint and maneuver.

As spring progressed, the order began locking down the island in preparation for a siege. Most housing outside the walls was pulled down to prevent it from providing protection for Turkish batteries. Rhodes’ inhabitants, fiercely proud of their own Greek heritage but loyal to the order, began moving into fortified strongholds after harvesting their crops early and putting the rest to the torch. The defense of the city was divided among the various nationalities, or langues, represented by the Order’s membership. The encompassing walls were divided by towers designated by the names of the order’s langues: France, England, German, Italy, and others. Within the main fortress, the roll of Knights and servants-at-arms came to about 600, along with perhaps 1,500 mercenaries and Rhodian militia. Small numbers of reinforcements were beginning to arrive as well. A number of Knights were still away in Europe—they might not arrive in time.

The order’s combatants wore various forms of armor. Knights were fully suited, although they also followed the tendency toward lightening the total weight by cutting down on armor below the back. The popular sallet, an opened-faced helmet that first appeared earlier in the 15th century, was far more practical than a full helmet with visor in the hot climate of the Mediterranean. After midcentury, sallets with visors that kept the lower face open to the air were increasingly popular. The brother sergeants wore a breastplate or part armor to the knees and any of the various forms of sallets.

In weaponry the order was well supplied with: light and heavy cannon, bombards (large mortars), and a large array of personal weapons including the old standby crossbows and longbows. Most importantly, they laid in a large stock of .50-caliber arquebuses with an effective range of close to 100 yards. The members of the order were superior swordsmen—still their traditional primary weapon of choice. They used cut-and-slash swords such as the short falchion for in-close fighting and various cut-and-thrust swords, from the typical broadsword to hand-and-a-half and two-handed swords for heavier work. The falchion, which had resurfaced in the middle of the 15th century, was particularly favored. Its can-opener-like point and concave back edge made it an effective thrusting sword against armor as well as cutting sword against flesh.

Greek Fire

The order had secret weapons as well. Incendiaries of various sorts, such as the famous “Greek fire,” which had been concocted in the 7th-century Byzantine Empire to keep Asian hordes away from Constantinople’s gates, were carefully prepared. The central ingredient of Greek fire was a petroleum base that combined other parts of the traditional Byzantine formula—naphtha, pitch, pounded sulfur, and charcoal. Its terrible effectiveness was enhanced by the fact that it could not be extinguished by water. The order had its own brand of Greek fire called “wildfire,” which contained other ingredients, including ammoniacal salt, that were poured into various terra cotta “fire pots.” Lengths of fuse were wrapped around the handheld variety for time detonation, making them early firebombs. The pots were also filled with gunpowder like hand grenades. Wildfire was poured down long metal tubes called “trumps” and forced out with huge bellows that made very effective flamethrowers. These trumps were directed over the walls and down on the upraised faces of scaling besiegers.

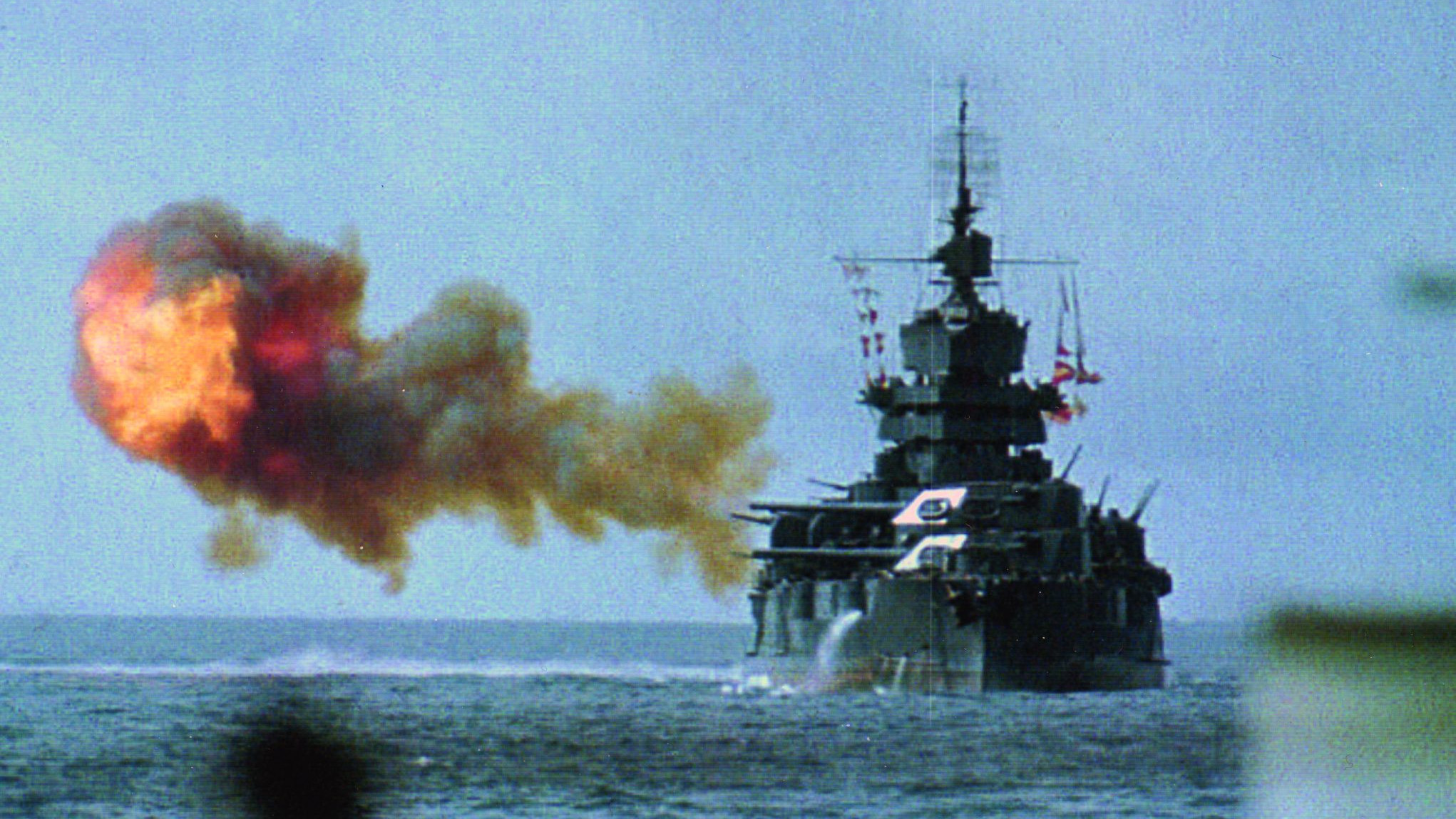

All day on May 23 Turkish ships moved out from the Asia Minor coast toward the northeast coast of Rhodes. At dusk they moved on Akra Milos at the northern tip of the island and sailed along the northwest coast, anchoring in the protected Bay of Trianda behind Mount St. Stephen, where Rhodian lookouts had been stationed for months. The next morning the Turks landed and moved around the north end of the island, heading for Rhodes. Mohammed II was a great cannon enthusiast and had his armorers cast what were the largest field pieces of the time, basilisks, when he made his assault on Constantinople. These basilisks were made of bronze, which was a good enough medium for early cannon, but they required great thickness and heavier designs to withstand gunpowder detonation. A logical innovation was the so-called “split cannon,” a siege gun that was divided into two sections to make it easier to transport. Each bronze basilisk weighed 18 tons; they were 18 feet long and had a 25-inch bore that fired stone balls 7 to 9 feet in circumference. Such cannon, used as Turkish shore batteries, could throw a projectile as far as a mile.

With the great army came a full complement of siege cannon, including three great basilisks. The Turks’ main strategy was to use these basilisks to bombard the tower of St. Nicholas, seize it, and then bring their fleet through the galley harbor to the very gates of the city. The carriages for the pieces were large-timbered beds constructed at the proper trajectory, with a massive recoil bed at the rear. With these at the ready, Turkish gunners set up the basilisks in the garden of a church roughly opposite the entrance to the galley harbor and began to work on St. Nicholas, directly across the water. D’Aubusson knew that blocking the harbor entrance was vital to his defense. The order’s strategy centered on holding St. Nicholas and the mole upon which it sat at all costs, helped by the fine array of cannon on the main wall held by the French Knights. The Order also used large-caliber, 25-inch mortars within the confines of the fortifications. The Turkish basilisks were countered by a battery of three huge bombards behind the walls on the enemy’s right flank.

Artillery Bombardment Around Rhodes Grew More and More Intense

Once the Turks had essentially ringed the city with batteries, the bombardment of Rhodes began. Their master gunner was a renegade German military engineer and ordnance expert known as George Frapan, or Master George, who had been one of many foreigners at Constantinople urging the sultan to attack Rhodes. He reportedly had helped the Turks crack open many a city in their string of conquests. Now he boasted that “no wall yet built could resist the fire of my artillery.”

The bombardment grew ever more intense. Within Rhodes, the most vulnerable portion of the populace—the old and infirm, women and children—were partially protected in the many cellars honeycombing the city. The launching of various incendiaries into the city was foiled by the order’s expert fire teams, which knew quite well how to extinguish Greek fire. But the continuous cannon fire soon began to take its toll. After several days, D’Aubusson wrote that the Turks had destroyed nine towers and brought down his palace. The 24-foot-thick walls of the St. Nicholas tower had withstood 300 rounds from the basilisk battery before cracks began appearing on the western face.

D’Aubusson had continued to reinforce the tower along the all-important mole, although Turkish arquebusiers and crossbow-firing archers tried to prevent it. They, in turn, were kept busy by crossfire from defending arquebusiers sheltered along the mole and in hidden entrenchments at the south end of the galley port. The western wall of St. Nicholas soon collapsed, and D’Aubusson commanded knights and peasants alike to immediately help repair it. Here began a process that would be played out again and again throughout the siege. Night and day, the stones and mortar of the west wall were built back up, while the mole was reinforced with a rampart along its length. Timber palisades were erected before both. D’Aubusson picked one of his best knights, Fabrizio del Carretto, to command the reworked defenses of St. Nicholas with a company of Knights, arquebusiers, and crossbowmen.

Misac Pasha, in charge of the overall Turkish effort, was beginning to see that Rhodes was not going to fall without significant losses. When a Sicilian ship with a cargo of grain and a hundred volunteers was able to enter the harbor, Misac became enraged and redoubled the bombardment of St. Nicholas. Before dawn on June 4, with their wild music wailing through the dark, Turkish ground troops appeared out of the gloom on galleys stripped of all sailing gear and modified with a platform built out over the bow. The troops were the best the sultan had to offer: Sipahis infantry and the most feared of all Turkish infantry, the Janissaries—adolescent Christians taken in raids and then brainwashed and trained to be the most fanatical of Muslim foot soldiers. As the troops jumped into the shallows of the mole, they were encumbered by sharpened stakes secretly set into place by the order.

The Knights Sent the Turks Reeling With 2-Handed Swords

If they thought there would be little resistance, they were sorely surprised. The order’s brother-sergeant arquebusiers opened up on the attackers, accompanied by a hail of crossbow bolts and longbow shafts. Fire pots and grenades screamed through the air. Above, on the main walls, cannon and bombards found their marks and began mowing down the attacking force. Those assailants who made it up the rubble of the mole to the palisades were met by the fully armored might of the order. In close-quarter defense, the Knights stood side by side and wielded their infamous two-handed swords with a barrage of arcing strokes that sent the Turks reeling backward. The surviving half of the original force finally retreated, only to find that one transport galley had caught fire and exploded. Two subsequent attempts to breach the walls were also unsuccessful.

Misac was now growing anxious about trying to take the mole and St. Nicholas—he was way behind schedule, and his tactics obviously needed readjustment. Reasoning that the older walls of the city were more vulnerable, he brought an eight-cannon battery into place to bring down the southern walls overseen by the Knights of England, Provence, and Italy. At the same time, he implemented diversionary bombardments at the north walls, and cloudbursts of incendiaries and shot rained down into the city to keep the Knights busy.

D’Aubusson knew that the beating given to the southern walls, particularly near the Tower of Italy, would inevitably do its job. Anticipating the collapse of the Italian section of wall, he set every able-bodied person to work night and day, building a secondary defensive line and ditch behind the walls. This involved tearing down houses, using timbers and dirt to build a line of palisades, digging trenches, and collecting a supply of masonry, wood, and earth to fill the breeches in the weakening walls of Italy. The ditch surrounding the battlements at Rhodes was shallowest at the point manned by the Tower of Italy. The Turks, digging trenches of their own toward the tower counterscarp (the slope of earth on the outward side of the ditch leading up to the rampart wall), rolled up wagons of stones to fill in the ditch. This proved counterproductive when miners inside Rhodes dug tunnels into the ditch and simply removed the stones during the night.

As the cannonading at the south wall continued, Misac kept up the pressure on St. Nicholas, knowing that D’Aubusson would not be able to spare reinforcements to defend both places at once. Beginning on June 13, four days and nights of bombardment of St. Nicholas masked the building of a pontoon bridge to reach from the main beach to the mole. On the 18th, under the cover of darkness, Janissaries carrying ladders and grappling hook-ropes mounted the bridge near the tower and began storming St. Nicholas. Already, 30 Turkish galleys and supply ships (called parandaries) loaded with cannon and munitions had moved undetected down from the north of the island to collect at the seaward sides of St. Nicholas. Aboard were Sipahis, Janissaries, and various irregular troops who splashed into the water and climbed up the seaward end of the mole on either side below St. Nicholas.

As Many as 2,500 Turks Killed

Del Carretto was on his own, but the Grand Master soon joined him along with his huge nephew Antoine, the Count of Monteil, who had arrived with a retinue shortly before the siege began. Again and again, the Knights and their troops flung the Janissaries back as they came on, wave upon wave. Soon the shore gunners found their mark and destroyed the pontoon bridge, sending many Janissaries to a watery death. D’Aubusson had his helmet knocked from his head by a fragment of cannon shot.

When begged to withdraw from exposure, he retorted, “The place of danger is my place.” Cannonades, arquebuses, arrows, fire pots, and the prodigious swordmanship of D’Aubusson and the other Knights foiled all attempts to gain the tower. The fighting lasted through the night until 10 o’clock the next morning. Four Turkish galleys and several munitions ships were sunk. For three days, Turkish bodies bobbed all over the harbor and washed up on shore—the body count was reported as high as 2,500. Among the dead were Ibrahim Bey, the sultan’s son-in-law, and the galley commander Merlah Bey. For Misac himself, it was a tremendous loss—he remained brooding in his pavilion for three days. The Knights’ symbol of victory was almost too much to bear; the mole was decorated with the impaled heads of hundreds of Janissaries.

Holding St. Nicholas was a great victory, but it did not mask the fact that Rhodes was still in grave danger. There were several attempts at desertion. Some Italian Knights urged evacuating Rhodes when it was rumored that the sultan and 100,000 reinforcements were on the way. The Grand Master’s condemnation of such rumors was enough to put them to shame. There were, however, several prominent Ottoman deserters in Rhodes. Two unfortunate Turks who were believed to be behind a plot to poison the Grand Master were literally torn apart by the crowd as they were being taken to the scaffold.

The most prominent Turkish deserter was none other than Master George himself, who had shown up in the predawn hours of May 28 to join the defenders. Many of the Knights were personally acquainted with George and did not trust him—neither did D’Aubusson. George gave convincing advice and might be useful, but he bore watching all the same. He continued to offer such advice, but he also spread an undercurrent of fear about the strength of Ottoman ordnance. His deceit was finally realized when his subtle artillery-based scheme was unmasked. George would re-sight batteries at the Turkish positions, and the Turks then would reposition their batteries at new points along the walls. His desertion had been a ruse—he was providing information on the city’s weakest points to Ottoman gun crews. Under torture he confessed to being a spy and was summarily hanged for his trouble.

Another relief ship from Italy loaded with stores of supplies, pikemen, and arquebusiers landed safely, but there would be little time for celebrating inside the city. The attempts on St. Nicholas were only a foretaste of the massive assaults that would be coming against the fast- weakening south walls of Rhodes.

D’Aubusson’s refortification and retrenchment efforts there were nearing completion, but Turkish trenches and batteries came ever closer to the counterscarp and ditch below the growing rubble of the walls. Aided by the Knights’ sallies to disrupt the Turkish forward batteries, the new defenses were completed in late July. On the 27th, the bombardment of the south walls stopped and the Ottomans prepared to launch another assault. During the night, Misac brought up most of his big guns and concentrated one last massive barrage on the tower. Defenders were driven from the walkways on the city side of the walls. The bombardment lasted until dawn on the 29th, then the Turkish commander unfurled a black flag, symbolizing that Rhodes would be sacked and no quarter would be given. Misac ordered the making of hundreds of wooden stakes—he meant to impale the entire male and female population above the age of 10.

Pikemen, Artillery, Booby Traps

The best of the Order’s fighters, along with and mercenary pikemen and arquebusiers, took up positions behind the south wall retrenchment, a 2-foot-high wall built up with earthworks of hardened soil and branches that sloped down to the cleared area that had been the Jewish Quarter. The position was booby-trapped with concealed ditches. Beyond this no-man’s- land was a semicircular ditch stretching between the crumbled breech of the 20-foot-high, partially destroyed Tower of Italy and the Tower of Provence. The rubble from the main wall filled the outer ditch, making it easy for the enemy to jump from the counterscarp beyond. Aware of this, the order had amassed a huge cache of incendiaries behind the new works and set up a crossfire with arquebusiers and crossbowmen on the walls adjacent to the Tower of Italy and the Tower of Provence.

Once the bombardment had sufficiently softened up the besieged city, the Turks moved into assault formation. In the front ranks were the most irregular of Turkish irregular troops—the Bashi Bazouks—untrained mercenaries from all over Eastern Europe and western Asia, many with no interest except plunder. This ill-disciplined rabble was followed by a line of Turkish provosts with whips, flails, and maces to keep them from retreating. Behind them would come regular Turkish infantry— the Iayalars, Sipahis, and Janissaries. But as a single shot rang out to start the Turkish advance, waves of screaming Bashi Bazouks were followed by lines of Janissaries armed with spears and Kilij sabers. Misac had decided to put his most determined troops in a position to be first over the walls. The Bashi Bazouks were expendable cannon fodder; their bodies would help fill any uneven places in the ditch and inside the south wall of the city.

As the irregulars swarmed over the convenient rubble leading to the base of the Tower of Italy, a hail of arquebus shot and arrows felled many of them. If D’Aubusson had not thought of it before, the first wave of the assault reminded him of the undefended walkway on the wall just beyond the Tower of Italy. As soon as he saw a Turkish battle flag planted on the tower ruin, D’Aubusson moved into action. Although he was lame from a recent arrow wound to the thigh, he led a dozen Knights to the breach near the base of the Tower of Italy, where ladders led up to the walkway. Climbing the ladders in their full armor, the Knights blocked the way of the swarming Janissaries and Sipahis. The defending arquebusiers and crossbowmen at the retrenchment and on the walls near the Towers of Italy and Provence kept up a withering fire, tumbling the enemy from the walkway and the steep rubble. D’Aubusson was wounded three or four more times in the melee. Suddenly, a huge Janissary rose before him and hurled a spear pointblank into his breastplate, puncturing a lung. As D’Aubusson began to stagger, he was caught by his Knights.

The Devastated Turks Burned Their Dead to Stave Off Disease

The Knights took back the tower and brought down the Ottoman standard. They were joined by the brother sergeants and continued to press the Bashi Bazouks and other Turkish warriors, who began to shout in panic and retreat down the rumble. But there was nowhere for them to go. The panicked mercenaries were cut down from behind by maddened Janissaries. Pressed forward by their onrushing comrades, the hemmed-in Janissaries in turn were hacked to pieces by the frantic Bashi Bazouks. Meanwhile, three giant standards that D’Aubusson had brought with him, bearing the brilliantly colored images of the Order’s cross, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist, terrified the ignorant Bashi Bazouks, who were unfamiliar with depictions of human images, which was forbidden by Islam. Confusion and panic reigned in the Turkish ranks.

Whatever the reason for the debacle, it swiftly took on the proportions of a miracle. The entire Turkish host dissolved in mass confusion and began retreating headlong toward their lines. The opportunity was not squandered by the battlewise Knights. D’Aubusson’s nephew, Antoine, led a counterattack that surged over the retrenchment and down the walls to slaughter the fleeing enemy “like swine,” as one witness somewhat uncharitably recalled. The Turks were chased back through their forward battery emplacements and around the walls into their camp on the slopes of St. Stephen. The sultan’s personal standard of gold and silver was captured. A force of 300 Janissaries who had made it from the Tower of Italy into the city and massacred some helpless citizens was quickly surrounded and cut down. By the time the defenders marched back into the city, enemy dead were strewn everywhere—around the city ditch, on the beach, and in the harbor. In all, some 4,000 Turks fell that day.

Exhausted, the Knights left Misac and his defeated army alone for the 10 days it took them to retreat from the island. The Turks had had enough. They gathered more than 15,000 wounded and burned their dead comrades to stave off disease. The order, which also burned its dead, had lost 230 Knights and many more brother sergeants, militia, and private citizens. The defenders of Rhodes watched the Turkish squadron abandon the harbor at Trianda late in the afternoon of August 7. As the invaders’ ships labored and thrashed through a quickly developing storm, a well-armed carrack flying the papal flag of the king of Naples suddenly appeared on the horizon. The Turks, fearing that it was the long-rumored European armada sailing to rescue Rhodes, turned in desperation to fight. Again they were outgunned, and delighted Rhodians cheered as they continued their retreat. Pope Sixtus IV had sent his promised food and token reinforcements—it was enough to ice the victory. But the best news of all was that D’Aubusson, thought to be on his deathbed, would live to fight another day.

A Self-Ordained Holy Mission

The fate of commanders who failed the sultan was usually summary execution, but Misac somehow avoided Mohammed’s full wrath and was exiled instead to Egypt. The sultan had every intention of returning to Rhodes himself, but his attention was turned to more pressing military matters in Asia Minor. In April 1481 he died while on the march to Nicomedia. The chroniclers in Europe announced his death with unconcealed delight and crowed that the sultan had “descended into Hell.” The Ottoman Empire was left with a legacy of civil wars and royal rivalry that carried over well into the early 16th century.

As for the Order of Knights Hospitallers, they would spend the next several years rebuilding Rhodes. D’Aubusson was raised to the rank of a cardinal of the church and died as one of the greatest Grand Masters in 1503. The order’s work went forward, adapting the latest European fortification and gunpowder technology to the rebuilding of Rhodes, which remained an eastern bastion of Europe against the might of the Ottoman Empire for four more decades. There was certainly no lack of the order’s most intangible weapon in its arsenal—its consummate will to overcome any and all obstacles to its self-ordained holy mission.

Join The Conversation

Comments