By Kevin M. Hymel

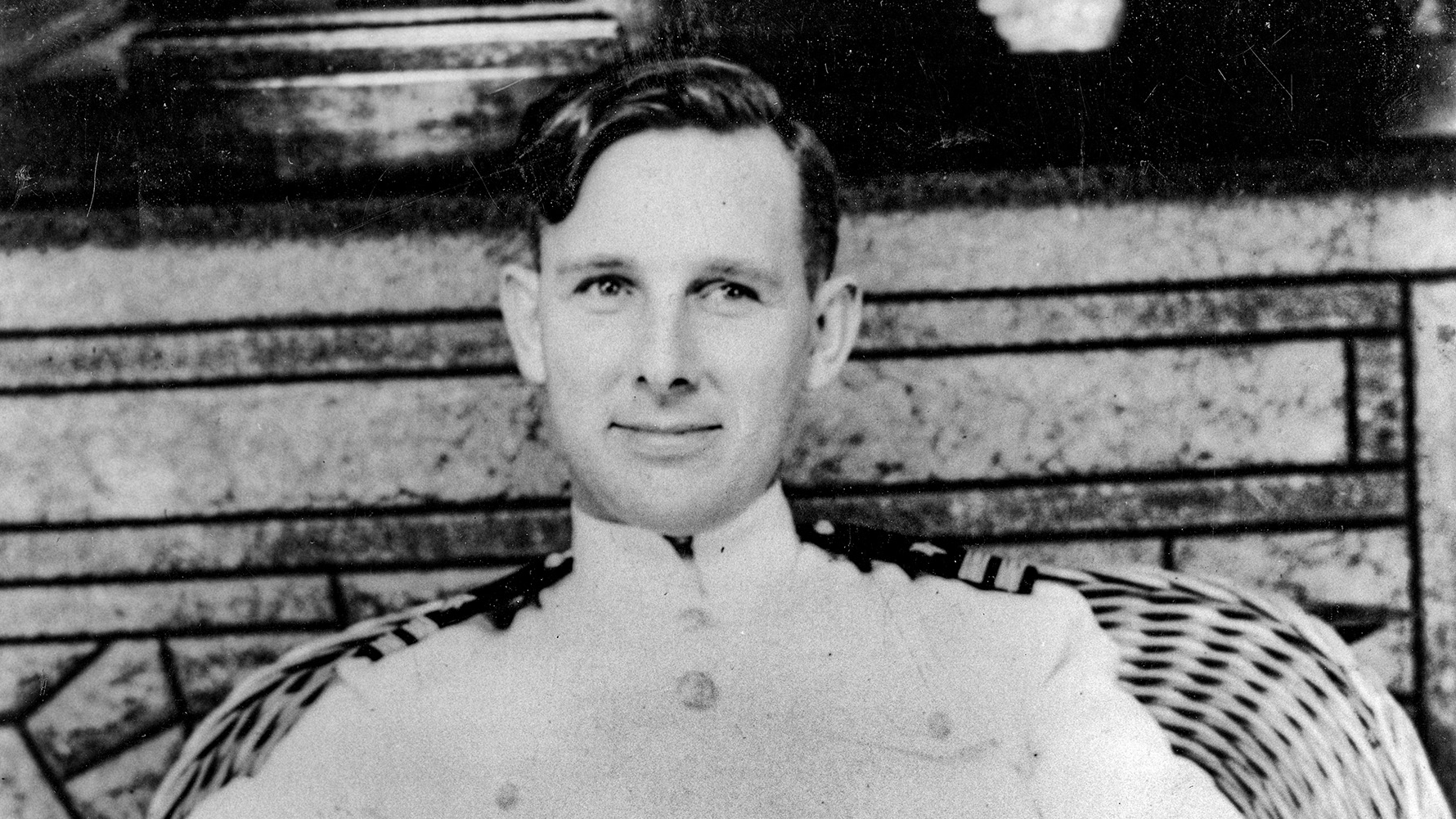

It was December 19, 1944, one day before the Siege of Bastogne. Shortly after 10:30 am, 26-year-old Major William Desobry picked up his field telephone, called his combat commander, Colonel William Roberts, and asked if he could withdraw from the Belgian village of Noville. Desobry had been holding off the entire German 2nd Panzer Division—some 16,000-men with more than 120 tanks and assault guns—for the last six hours with only 400 men and a handful of tanks and tank destroyers.

With so many Germans bearing down on him, Desobry knew that staying could mean suicide. Roberts, from his Bastogne headquarters in the Hotel LeBrun, gave an answer that probably made Desobry’s blood run cold. He told the young officer to hold the phone line.

With the sounds of battle reverberating against his headquarters walls, Desobry held the line. After what must have seemed like an eternity, Roberts came back on the line. “You can use your own judgment about withdrawing,” he said, “but I’m sending a battalion of paratroopers to reinforce you.”

With almost 500 airborne soldiers heading his way, Desobry decided not only to stay but to attack. What had started as a day-long holding action became a major two-day battle, pitting a scratch force of Americans against a battle-hardened German division. The Battle of Noville helped decide the defense during the Siege of Bastogne and the fate of the entire German Ardennes offensive—the Battle of the Bulge.

When the Germans launched their counteroffensive through the Ardennes Forest of Belgium and Luxembourg four days earlier, on December 16, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, immediately sent his 7th, 9th, and 10th Armored Divisions into the fray. Two of the 10th Armored’s Combat Commands, CCA and CCR (R for Reserve), each about the size of an infantry regiment, headed to Luxembourg City to hold the southern shoulder of the rapidly developing bulge, while Colonel William Roberts led his CCB to Bastogne, Belgium, to receive orders from Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, the VIII Corps commander.

By December 18, an entire German panzer corps was barreling straight for Bastogne, and Middleton, outnumbered two to one, needed to buy time while more forces were brought to bear. The Germans had already sacked his 2nd Infantry Division and were grinding down his 9th Armored.

Middleton asked Roberts to break his command into three teams and defend Bastogne’s north, east, and southeast approaches. Roberts created three teams to hold the positions, each named after its commander. To the southeast he assigned Team O’Hara, to the east he assigned Team Cherry, and to the north he sent Team Desobry, consisting of soldiers from the 20th Armored Infantry Battalion and 15 Sherman tanks.

When Major Desobry learned of his assignment, he asked Roberts, “If the situation gets to the point where I think it’s necessary to withdraw, can I do that on my own or will I need permission from you?” Roberts paused, but then told him, “You know, Des, you will probably get nervous tomorrow morning and want to withdraw, so you had better wait for any withdrawal order from me.” With that, Desobry led his team through heavy winter fog toward the town of Noville.

Noville, three miles north of Bastogne, stood like an island amid flat farmland. It consisted of a handful of brown and gray stone homes, farmhouses, and buildings, with a church whose tower dominated the landscape. A mile to the south stood the town of Foy, on the edge of the woods surrounding Bastogne.

North of Noville the ground remained flat until it sloped up to ridges about 500 yards northeast and northwest of the town. The key to Noville was the intersection of the north/south road, N30, and an east/west road, ND77. Team Desobry had to hold that intersection.

Just as determined to capture Noville were the tankers of Maj. Gen. Meinrad von Lauchert’s 2nd Panzer Division. Lauchert needed to secure the town’s crossroads to continue west to the Meuse River and reach the German counteroffensive’s ultimate prize: the Belgian port city of Antwerp.

He did not have orders to take Bastogne, but if he blasted through Noville quickly while other German units were stalled to the east, he might be able to bag the town and its seven intersecting roads. Lauchert’s division counted 27 Panzer IV medium tanks, 58 Panther heavy tanks, and 48 assault guns, for a total of 133 armored heavy-weapons vehicles when it started heading west on December 16.

Once Desobry’s men reached Noville, they occupied the buildings around the intersection and smashed out windows with their rifle butts to prevent flying glass once the shooting started. Desobry, meanwhile, set up his headquarters in a schoolhouse cattycorner from the church. He then sent out three patrols to make contact with the enemy and told half his remaining men to get some sleep.

Each patrol consisted of two tanks and an infantry squad. He sent one northwest, the other directly north, and a third directly east to set up a roadblock outside of the village of Bourcy. His engineers were not allowed to lay mines since American stragglers would be coming through the lines. Desobry hoped to incorporate them into his defense.

Sure enough, stragglers intermittently passed through the outposts until around 4:30 am on December 19. Almost an hour later, a column of half-tracks approached the Bourcy roadblock. In the dark and fog, the sentries could not discern friend from foe until they heard German spoken in the lead vehicle. They immediately tossed hand grenades into the half-track’s open beds, which exploded among the packed infantry.

As wounded Germans screamed, others piled out of the half-tracks and opened fire. One of the sentries took a bullet in his cheek. Others tossed the rest of their grenades at the oncoming Germans, but, surprisingly, their support tanks did not fire a shot. The tankers were blind in the darkness and did not want to risk hitting their own armored infantry. After a 20-minute firefight, both sides pulled back and reported to their superiors that they had found the enemy.

In Noville, Desobry had slept for about an hour when he was woken by the sounds of explosions and gunfire to the east. He left his headquarters and stood outside, listening to the fight. He heard the distinct sounds of German armor circling to the north, then distant fire.

He did not know it, but he was listening to the destruction of elements of the 9th Armored Division. Task Force Booth, led by Lt. Col. Robert Booth, had retreated from a position east of Noville and had run into some German vehicles and infantry near where the Germans clashed with Desobry’s sentries.

Booth’s tanks and infantry quickly dispatched the Germans, then headed north and occupied the town of Hardigny, northeast of Noville. There they knocked out about a dozen enemy half-tracks and infantry, but before they could celebrate, German tanks and infantry surrounded them.

Task Force Booth had stumbled into the 2nd Panzer Division’s assembly area. The Germans quickly destroyed the American tanks and rained mortars on the infantry. The surviving Americans broke for a nearby wood, where the Germans hunted them down. They captured Booth, hobbled by a broken leg, but more than 200 men escaped to Bastogne, where they would continue to fight.

Task Force Booth took some of the pressure off Desobry. Every single German bullet, tank shot, and mortar round fired at Booth’s men was one less firing at Noville.

Back near Noville, the enemy column that Desobry heard soon encountered the sentries on the north-south road. One of the two Sherman tanks opened fire first, but its round exploded short. The lead German tank then fired six rapid shots, disabling both Shermans. The two burning tanks now blocked access to the town. Other German tanks spread out and fired their machine guns at the American infantry. Machine gunners in the town returned fire as the two sides sparred from a distance until Desobry ordered his patrol back into Noville.

Once the fighting died down, Desobry pulled all his outposts back toward the town. In the dense fog, small skirmishes broke out as the Germans probed the lines. The Americans could hear the enemy shouting orders in the dark. At some point, a German sniper wielding an assault rifle found a perch in a house’s crawlspace across from Desobry’s headquarters and fired at anyone coming in or out of the house.

At 10 am, the fog suddenly lifted and the men in Noville could finally see what they were facing. German tanks atop the hills to the north started rolling down toward them. The men spotted several German tanks driving down the main road, while some 30 panzers spread out in a skirmish line on a ridge to the west.

As the Germans bore down from the north, from the south raced a platoon of M-18 Tank Destroyers from the 609th Tank Destroyer Battalion. Desobry used the unit as his reserve and kept its platoon commander close. One tank destroyer crew west of the intersection scored a hit on the German lead tank. The crew then traversed the turret to the next panzer and fired. Before finding out if they had disabled the second tank, the crew retreated south. As it did so, American tanks and everyone else with a weapon opened fire on the advancing German tanks and infantry. The fight was on.

The Americans had little difficulty hitting the German tanks as they slowly rolled down the slopes. But then German artillery tore into the town as their armor edged toward the church. Just west of Desobry’s headquarters, a single Sherman knocked out three German tanks stuck in the mud on the western ridge. The crew followed up by disabling an enemy half-track. Another tank destroyer knocked out five German tanks.

Just then, two enemy tanks pushed down the north/south road toward Noville, but a self-propelled gun destroyed one panzer and a Sherman knocked out the other, further blocking the road. Inside Noville, a team of Americans located the sniper in the crawlspace and fired into it until blood dripped down.

In all the confusion, a pig raced down the street, tracers snapping around it. Soldiers called to it, trying to coax it to safety, until the pig darted into a house where some American soldiers grabbed it. A cheer went up among the Americans who decided not to eat the frightened animal, but adopted it as a mascot. The fighting quickly resumed.

American artillery smashed into a large group of German infantry approaching from the northeast, forcing them to pull back. American tanks and tank destroyers, well hidden among the town’s buildings, had managed to knock out 17 enemy tanks at the cost of one TD and four smaller vehicles.

After a lull in the fighting, a captured Sherman tank operated by the enemy rolled into town from the north and opened fire on several vehicles. “Get that son of a bitch!’ shouted an armored infantry captain. “I don’t care who he is!” A TD dispatched the Sherman and the German crew bolted from it but were quickly gunned down.

Later, when a second German sniper began firing from the church steeple, tank, bazooka, and small arms fire silenced him, wrecking part of the steeple.

Despite the success, Desobry knew he was blocked on three sides and the Germans held the high ground. He sent out reconnaissance patrols that failed to return. He knew that his small force was out on a limb. With the road south to Bastogne his only escape route, he contemplated a retreat, but then he remembered his conversation with Colonel Roberts the night before and placed the call.

In Bastogne, after Roberts told Desobry to hold the line, he put down the phone and walked outside his headquarters (today up the street, north of McAuliffe Square) to head to Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe’s headquarters. McAuliffe, the acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division in Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s absence, had arrived the day before and had taken over General Middleton’s headquarters as he awaited his division’s arrival.

As Roberts departed his headquarters, he ran into Brig. Gen. Gerald Higgins, the 101st’s assistant CG, and explained his dilemma. As they talked, the 1st Battalion of the 506th Parachute Infantry marched past. Higgins waved over Colonel Robert Sink and Lt. Col. James LaPrade, the regimental and battalion commanders, respectively, and ordered LaPrade and his unit to march immediately for Noville. Roberts raced back to his phone and told Desobry the news.

It was no accident that the 506th was marching through Bastogne at that moment. Four days earlier, after Eisenhower decided to commit his armor to the fight, he ordered into battle his only strategic reserves, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. The 101st paratroopers were resting and recovering in Mourmelon, France, after fighting for three months in the Netherlands, when they were called up only hours into December 18.

With whatever equipment they could find, the paratroopers boarded trucks instead of planes to reach their new battlefield. Most of the trucks did not have canvas covers, making for a cold ride. They rode through the night and into the day. The trucks drove with their headlights on, something almost never permitted at night. Some men succumbed to motion sickness and were forced to vomit into their helmets. Others relieved themselves in theirs. In both cases, the helmets were passed to the back of the truck to be emptied.

The 101st was not headed for Bastogne but farther north to Webermont. By happenstance, McAuliffe stopped at Middleton’s VII Bastogne headquarters for instructions and Middleton told him to bring his division to Bastogne. Before McAuliffe could act, another coincidence helped bring the 101st to Bastogne.

When the 101st’s 380-truck convoy got stuck in traffic behind the 82nd, Colonel Thomas Sherburne, the 101st’s artillery commander, decided to cut through Bastogne about 15 miles to the west, bypassing the backup. After an MP told him that General McAuliffe had used the same road on his way into Bastogne, Sherburne directed the trucks east.

Soon the convoy encountered another blocked road at the town of Mande-St.-Etienne. Once the blocking vehicles were cleared, the column was stopped again by a wave of retreating humanity. Soldiers, mostly from the 28th Infantry Division, limped, slogged, and stumbled east, telling the paratroopers what was in store for them. Some offered up their ammunition and equipment. The paratroopers would have to travel on foot the last three miles to Bastogne.

Elements of Colonel Julien Ewell’s 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment reached Bastogne first and headed east to join Team Cherry, which the Germans were attacking. Colonel Sink’s 506th came next and was marching north through the town when he encountered General Higgins and Colonel Roberts. Thus, LaPrade’s 1st Battalion received its orders while on the move.

Back in Noville, Desobry’s feeling of relief proved short lived. Word of his retreat request had reached his armored infantrymen, who began leaving their positions and preparing to pull back. Fortunately, sergeants and officers talked them back to their positions, assuring them that no such order had been issued.

With that small crisis over, Desobry decided the only way to hold onto Noville was to attack the Germans on the surrounding ridges, and he hoped LaPrade would be game for such a fight. He need not have worried. LaPrade, a 30-year-old West Point graduate, had been with the division since D-Day and had commanded the battalion through the Netherlands campaign.

Desobry knew that it would take a while for LaPrade’s battalion to reach him, so he sent a jeep to retrieve the airborne officer so they could devise a battle plan. LaPrade arrived around 11:30 and they devised a two-pronged attack on the ridges. While four tanks and armored infantry provided cover fire on the north-south road, LaPrade’s A and B Companies would assault the heights.

Meanwhile, three tanks and armored infantry would do the same on the northeastern road, while LaPrade’s C Company would charge. The attack would be supported by a five-minute artillery preparation, followed by smoke rounds.

To make sure everyone understood his objectives, Desobry ordered another jeep to pick up LaPrade’s A, B, and C company commanders. Desobry then led them onto the battlefield where their attacks would commence, ducking machine-gun fire as they went.

When LaPrade told Desobry that his men lacked arms, ammunition, and other basic equipment, Desobry dispatched Lieutenant George Rice two miles south to the town of Foy to gather supplies and distribute them to the advancing men. Rice did his job. As LaPrade’s men neared Noville, they discovered piles of ammunition. Supply men tossed rifles to the paratroopers who needed them. There were also bandoliers of ammunition, mortar rounds, and precious hand grenades.

The paratroopers then halted on a rise about 500 yards short of Noville and waited for the preparatory artillery barrage. As they waited, they watched a Sherman tank take a hit and the crew bail out—not an inspiring scene. Then the barrage crashed into the German lines and the paratroopers took off, first walking, then running.

The paratroopers entered a town filled with burning buildings, destroyed vehicles, and dead bodies, some of which had been covered with civilian blankets. One replacement turned around and ran, only to be floored by a veteran who threatened him at gunpoint to resume his march.

Enemy artillery exploded in the main street and shook nearby trees. Men went down or leapt into doorways to escape the fire. One paratrooper jumped between two knocked-out jeeps and had to change direction in mid-air when he saw two of his dead comrades lying in front of him. Paratrooper scouts sprinted ahead of the main body until they reached two Sherman tanks across the main intersection firing on the Germans.

The scouts watched as the two tanks knocked out tank after enemy tank. The fire from both sides was so intense that they could see German tanks exploding but could not discern which Sherman had fired the shots. The scouts had to leave their prone viewing spot when one of the Shermans backed up and almost ran over them as it smashed into a house while maneuvering into a firing position, spinning its treads in the process. The other tank darted about, dodging German fire.

Inside the tanks, the tankers sweated despite the cold as they pushed their machines to the limit. “Those 10th Armored tankers worked so fast,” commented one of the scouts, “that even we thought there must have been at least four tanks at the entrance to town and in the tree line.”

As other paratroopers reached the northern edge of town, they sprinted for the ridges they could barely see. Despite their speed, they remained organized and under the control of their officers. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” Desobry later admitted. They made it about halfway up the ridges when they ran into the Germans, who were commencing another attack. Caught in the open, the paratroopers made easy targets for the tanks.

Because of the blinding smoke, Desobry’s supporting tankers offered scant fire for the exposed paratroopers. Oddly enough, the German tanks advanced alone. Their infantry was reluctant to charge after the blooding they had received at Desobry’s hands earlier in the day.

Some A Company paratroopers charged forward and dove into a pigsty, where they paused and lit cigarettes. When an enemy tank edged over the ridge in front of them, they ran for the safety of a haystack, but German tank fire set it ablaze, forcing the men to crawl away.

When they tried running from the area, the panzer chased one paratrooper down a small road. The paratrooper ran all out as bullets kicked up sparks near his feet. He turned around, saw the main gun pointed right at him, and dove into a house where other paratroopers had taken refuge. They all escaped out the back door as the tank fired a round into the house, destroying it.

Some of the paratroopers never got started. Enemy fire pinned down part of A Company in the church cemetery. The men hugged the ground as tank rounds and artillery exploded around them.

East of Noville, the paratroopers of Company C met the same fate. Halted at the base of the ridge, the men retreated, dodging German fire as they went. One C Company paratrooper rounded a corner in the town, holding his own intestines in his arms. Two other paratroopers intercepted him and laid him down next to a raincoat. They let his intestines spill onto the raincoat, then cleaned the dirt out of them with canteen water before placing them back inside the man and bandaging his abdomen tightly. They quickly brought him to an aid station.

Desobry watched two Shermans duel with several panzers on the ridge “like a tennis match,” he later said about his head pivoting back and forth, following the fire. A sergeant watching the exchange in his armored car called to Desobry, “Major, I can hit that son of a bitch! Your guys stink!” The sergeant then aimed his 37mm antitank gun at one of the panzers and fired. His round hit two fuel-filled Jerry cans on the tank’s back deck. The fuel poured down onto the engine and exploded. The sergeant jumped up, clasped his hands together and shook them over his head like a victorious boxer.

German infantry eventually followed the armor into town, where men fought hand to hand in the blinding fog. Americans dodged German tanks from as close as 25 feet. “I could have spit on it,” recalled a soldier, “if my mouth had not gone dry.”

Desobry had to constantly order the north-south road cleared of damaged vehicles. Finally, he ordered a group of recovery vehicles to tow the damaged vehicles back to Bastogne.

A German tank headed into town and was near the church when a two-man armored infantry bazooka team blasted away from a house behind the church. Their first rocket hit the tank but did no damage. They reloaded, the loader patting the gunner’s head when the bazooka was armed, and fired again. This rocket ricocheted off the turret without exploding.

The tank backed up a bit, the turret slowly spinning, searching for the Americans. The men then fired 11 rockets at the tank, but they all just plinked off. Sniper fire and a tank round exploding on the second floor of the house rained wood and brick on the two.

The tank’s main gun started to lower. The bazooka team decided to fire one more round before escaping. The gunner fired a rocket into the small slit below where the main gun attached to the turret. The rocket exploded and the gun froze. They decided to fire once more to make sure the tank was dead but, just as the loader picked up another rocket, an explosion rocked the room and drove them both to the floor.

When they came to, they realized a tank destroyer had come up behind them and fired a shot into the enemy tank, turning it into scrap metal. Another TD pulled up and blasted another German tank.

So intense was the fighting that Airborne intelligence officers had to capture prisoners on their own for questioning—no one else was taking prisoners, especially after they had learned that the Germans had killed surrendering Americans. The paratroopers had been briefed before they left France about the Malmedy Massacre, where Germans killed 84 Americans after they surrendered at a Belgian crossroad.

Noville burned and the wounded screamed in the fog. The cries of horses and cows trapped in a burning barn added to the cacophony of sounds. The Germans had repulsed the Americans’ single effort to drive them off, but they could not penetrate Noville and pulled back. The small, lightly armed force of almost two battalions had withstood the second German attack.

The Germans tried again, this time with a single tank leading the charge, followed by infantry. The paratroopers of Company A heard the German tank’s approach, but since no one had a bazooka, let it pass. Then the infantry followed, firing blindly into the fog as the town’s flames lit up their silhouettes.

As the enemy approached, the paratroopers stood up as one and poured fire into their ranks. The Americans fired rapidly, reloading as soon as they heard their ammunition clips pinging out of their M-1 rifles. Soon the German infantry retreated to their ridge.

The enemy tanks, however, remained and fired at anything and everything. Nearby explosions blasted paratroopers out of their foxholes. They rolled back in, only to be blasted out again. Men ran around in confusion. The wounded screamed as more dead littered the streets and sidewalks. But without their supporting infantry, and with the roads blocked by burning tanks, the German tanks pulled back, keeping the town under fire.

Desobry was overseeing the repulse of some flanking German armor when one of his soldiers told him that the paratroopers were pulling out. He raced back to his headquarters where LaPrade explained that Colonel Sink had ordered him back to Foy.

“I can’t go back; I’m on orders to stay here,” Desobry retorted. “I’ve lost a hell of a lot of my men. Won’t you please stay with me?” LaPrade said, “I’ll try,” and called Sink, who agreed to let the paratroopers stay.

As the sky darkened, Colonel Joseph Harper from the 327th Glider Regiment arrived to assess the situation. Later, General Higgins joined LaPrade and Desobry. To help protect their headquarters and their high-ranking visitor, LaPrade blocked the north-facing window with an armoire.

Higgins placed LaPrade in charge since he outranked Desobry (the two had fought all day together without worrying about rank) and told them there would be no retreat. His parting words spoke to the dire situation: “Nobody’s getting out of here alive.”

Higgins departed, then Colonel Sink visited to check on his battalion. When he left, Desobry and LaPrade reviewed their plans for Noville’s night defense. As they poured over a map, a recovery vehicle pulled up in front of their headquarters. An officer climbed out and went inside to report to Desobry that all damaged vehicles had been removed and that he and his unit would be returning to Bastogne.

On the ridges northwest of Noville, the Germans noticed this strange vehicle in front of the building and surmised the building must hold something important. A tanker fired two rounds at Desobry’s headquarters. The shells tore through the armoire and exploded in the room. Both men were buried under a pile of debris. LaPrade was dead and Desobry had an eye ripped from its socket with deep cuts around his face and head.

Soldiers brought Desobry to the cellar where medics treated his wounds. He was then placed in an ambulance bound for Bastogne, where the dazed and concussed officer hoped to report to Colonel Roberts.

As the ambulance neared Foy, a German patrol halted it but let it go. It proceeded to Mande-St.-Etienne, where the 101st had set up a field hospital. A few hours later, the Germans overran the hospital and Desobry found himself in his ambulance heading east into Germany.

With the two leaders out of the fight, Major Robert Harwick, LaPrade’s executive officer, and Major Charles Hustead, Desobry’s deputy, took command of the combined force. Harwick had been late joining his battalion and, as he entered Noville, learned of LaPrade’s death and his immediate promotion to commander of Noville’s defenders. The two officers implemented the defense plan their superiors had agreed to.

Ass Harwick’s arrived, the defenders received some reinforcements: a dozen M-18 Hellcats from Lt. Col. Clifford Templeton’s 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, which had reached Bastogne early that evening after pulling back from Germany. The tank destroyer crews were exhausted, but they brought much needed firepower to the beleaguered force.

A few hours into December 20, the German artillery pounded Noville. Structures not already burning shook from the terrible salvos. Soldiers and civilians crowded the cellars, waiting for the volleys to relent. Before dawn, the paratroopers left their cover to prepare for the next attack. Through the fog they could see the burning vehicles and buildings as well as the dead Germans and Americans in the streets.

Major Harwick, the new commander, thought of home and wished he had a cup of coffee. His force was down to six Shermans and 21 TDs. Through the fog, however, he could see the toll the enemy had taken. “Those Krauts sure have a pot full,” he wrote. “Tanks all over the place.”

Enemy tanks came again, straight down the north/south road. A bazooka team fired at one from behind and it burst into flames. A Sherman tank took out another, firing at it straight down the east/west road. When the German commander climbed out of the hatch and tried to escape, a sergeant killed him with a BAR.

Another German tank rolled over a number of mines, exploding them without damaging the tank while it roared toward an airborne bazooka team in a house basement. The tank’s first shot wounded some of the men, and other panzers soon joined. One of the bazooka team members climbed the stairs and shot the lead tank commander standing in the hatch. The tanks then retreated north under a heavy American artillery barrage.

Elsewhere, a German tank turned its turret on one of Team Desobry’s company command posts, but before it could fire, the Sherman that had knocked out a tank firing straight down the road rotated to the right and fired three shots. None penetrated the tank, but the German driver reversed the tank and ran over a jeep which got stuck in the tank’s treads, sending it out of control and into a half-track. The collision tipped the tank over and its crew escaped into the fog.

Another Sherman crew spotted a group of German soldiers approaching from a slight rise and opened fire. The crew exhausted their ammunition, burning out their .30-caliber machine-gun barrel, but all the Germans were either killed or retreated.

When the Sherman’s bow gunner popped out of his hatch to replace the barrel, a German round almost tore off his arm, leaving it hanging by some flesh. He dropped off the tank but, just as he hit the ground, the fog lifted and a German tank fired a round that exploded in front of the vehicle. The wounded gunner took shrapnel but made it to the rear with the help of an Airborne medic.

One Airborne lieutenant pieced together a team of both paratroopers and armored infantry and led them out into the fog. They advanced stealthily until they spotted a German infantry squad. Quietly, the lieutenant had his men count off so they could each claim a German. Next, he ordered everyone to take a knee to steady their shots. Finally, he gave the order to fire. The men pulled their triggers, shots rang out, and the entire German squad went down. “The lieutenant made it look so easy,” said one of the armored infantrymen, “it was like shooting fish in a barrel.”

The German attack into Noville had been a ruse to cover a flanking attack to the east. When the fog lifted, the tank destroyer crews south of Noville could observe the flanking tanks and blasted them as quickly as possible. One TD crew knocked out five German tanks before their vehicle took a hit. A German tank rolled over a foxhole manned by two paratroopers and stopped. The men worried they would be buried alive but the tank soon moved on, and the paratroopers gunned down the followup infantry.

But ammunition was low, tanks were running out of armor-piercing shells, and the Germans were flanking Noville. Losses in the 1st Battalion opened gaps in the line. Noville’s two makeshift hospitals were packed with casualties. Worse, neither Harwick nor Hustead could contact their commanders. Harwick sent a paratrooper in a jeep to tell his leaders that they could not hold out indefinitely but he never heard back. When he learned that one of the tankers received a radio message to fight their way south, he took this as permission to retreat to Foy.

In Bastogne, McAuliffe and Roberts decided to divert the Germans’ attention at Noville by advancing on Foy with elements of both the 506th and 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiments; Noville’s defenders would use this window to withdraw.

In Noville, Harwick and Hustead planned to load the wounded onto vehicles. An armored car, followed by four half-tracks and five Sherman tanks would lead the way, accompanied by Company C of the 506th. The rest of the vehicles, almost all carrying wounded, would follow. Lt. Col. LaPrade’s body would also be taken to Bastogne. The rear guard consisted of a tank destroyer platoon.

When the last vehicle pulled out, engineers would set off explosives in the church steeple, denying it to German artillery spotters and hopefully blocking the road with debris.

At 1:15 pm, as the column organized, fog again descended on the area. It was the perfect cover. Vehicles pulled out of the town while artillery crashed around them. One of the armored infantrymen released their mascot pig into the woods to fend for itself.

Soon the column’s lead tank broke down and paratroopers dropped some thermite grenades into it. Adding to the confusion, the lead vehicle took off, racing for Bastogne, while the rest of the column inched forward in the fog.

As the last vehicle left the burned-out husk of what was once a charming village, the engineers detonated the charges in the church, collapsing the steeple into the street.

At the head of the column, the lead vehicles neared Foy but were suddenly stopped. The armor plate above the front slit of a half-track’s driver’s shield slid down and the driver reached out to push it back up. The officer next to him thought the driver had been wounded so he yanked the hand brake. The vehicle screeched to a halt while the vehicle behind it rammed the half-track. Throughout the slow-moving column, vehicles collided with each other, creating a traffic jam.

Seeing this, the Germans opened fire. While the column prepared to resume, two Sherman tanks broke from the column and headed southeast through an open field to engage German machine gunners in a house outside of Foy. Once they had set it on fire, one tank backed away while the other pressed forward.

From behind a row of trees near Foy, three German tanks opened fire on the advancing Sherman. There was a sharp explosion and the men in the column could see a bright orange glow through the fog. The Germans destroyed the other tank and began firing into the column.

With so many tankers killed or wounded, paratroopers began driving tanks or manning other tank positions. One of the Shermans made it into Foy but was hit. The crew scrambled out as one crewman grabbed the tank’s Thompson machine gun and fired at several approaching Germans.

Some Americans dismounted their vehicles and fought their way into Foy, while a procession of tanks and vehicles followed. Some manned the line southwest of Foy, tying in with Lt. Col. Lloyd Patch’s 3rd Battalion, 506th, while vehicles carrying the wounded continued streaming into Bastone. Greeting the exhausted, dirty soldiers as they reached safety was a single officer, shaking hands with the men along the road. It was Colonel Robert Sink, the 560th commander. The battle for Foy was over.

The cost of holding Noville had been heavy. Half of Team Desobry’s 400 soldiers had been killed, wounded, or captured in two days of combat. It had lost four tank destroyers and 11 of its 15 tanks. LaPrade’s 1st Battalion was also cut in half. Of the 473 paratroopers that rushed into Noville, 212 had been killed, wounded, or were missing. The battalion went into reserve for the next month.

But the Americans took a disproportionate toll on their enemy. They destroyed at least 30 German tanks and inflicted some 600 to 800 enemy casualties.

The Americans had scored victories in three directions. First, by putting up such a tough fight, Maj. Gen. Meinrad von Lauchert’s superiors refused to let his 2nd Panzer Division attack Bastogne once he captured Noville.

Second, the tankers and paratroopers also gave the rest of the 101st Airborne precious time to deploy around Bastogne’s perimeter. Finally, by holding Noville for as long as they did, the Americans delayed the 2nd Panzer from attacking westward to Antwerp by at least 48 hours, giving the rest of the Western Allies time to race reinforcements to block the German attack.

The hard-fought battle was a solid American victory, but it may not have happened if 26-year-old Major William Desobry, who wanted to withdraw from Noville, had not picked up a phone and waited for his commanding officer to give him options.

The Civilians of Noville

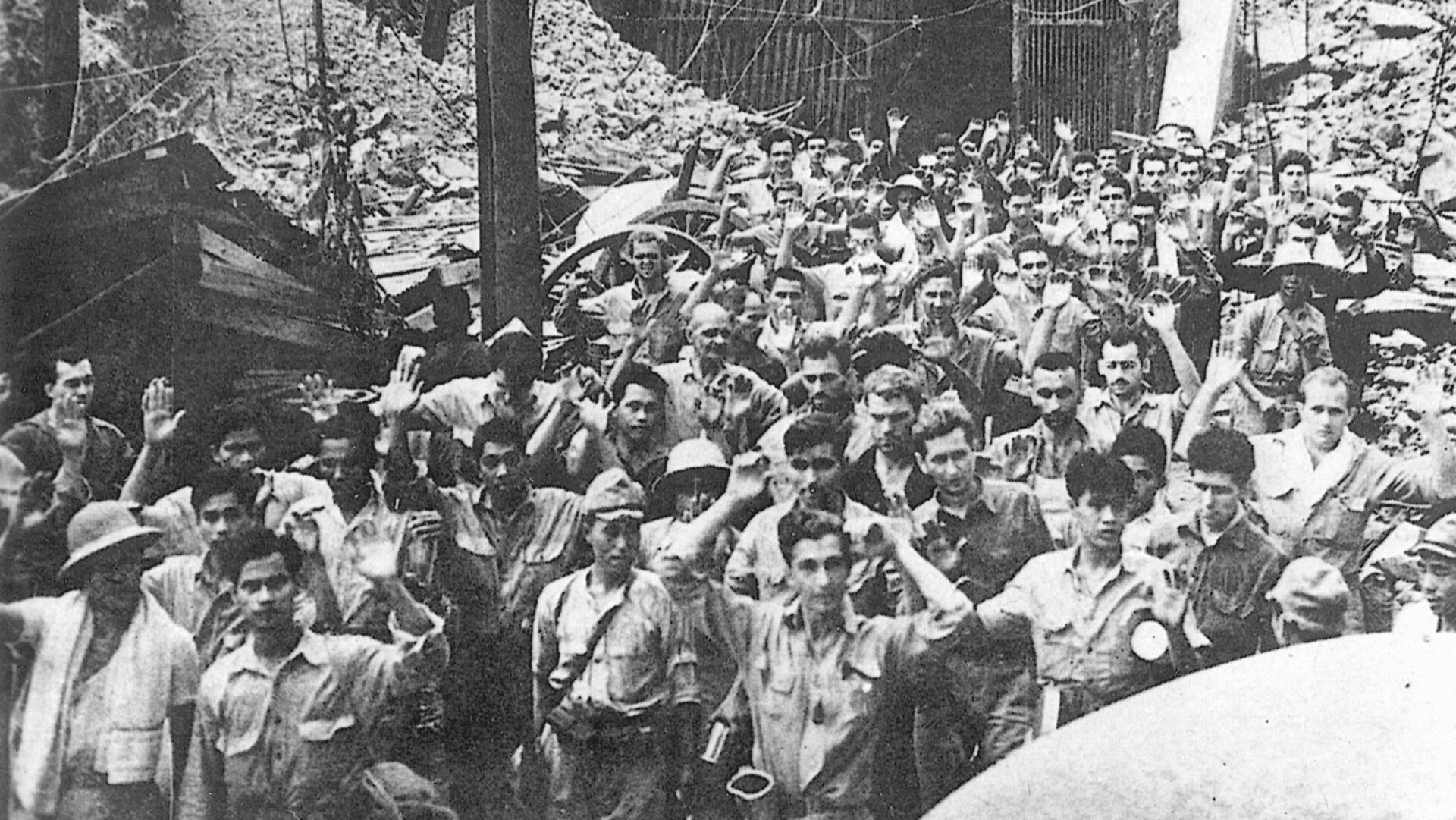

When the American Army liberated Noville in September 1944, the civilians poured into the streets and cheered their liberators. They took pictures of themselves with the young Americans, never suspecting the Germans might return. But the Germans did, despite the American tankers, armored infantry, and paratroopers holding them at bay for two days.

While the battle raged across the streets of Noville, eight-year-old Andre Meurisse and his parents stayed at a nearby farmer’s home. Whenever the shelling paused, the farmer ran out, milked his cows, and returned with a full pail. He eventually lined up five pails of milk, offering some to his guests. Suddenly, two Germans barged into the house. They each picked up a pail and drank as much milk as they could. Once they finished, they urinated into the rest of the pails and left.

It was different with the Americans. When an old man spotted paratroopers on patrol outside his house, he gathered up some bread and wine and brought it to them. The paratroopers, appreciating his gratitude, happily accepted his offering.

After the German 2nd Panzer Division finally entered Noville around noon on December 20, a German reprisal unit soon followed. They discovered the pictures of the locals with the Americans and rounded up 16 villagers they identified in the photos.

The next day, the Germans put them to work clearing American equipment and debris from the road. After they toiled for an hour in the cold, the Germans lined up the civilians and a German officer read eight names from a piece of paper. “These eight may go back home,” he told them.

The other eight, including a priest, were led with their hands behind their heads to a field where the Germans had dug three graves. The men were lined up before the graves and shot one by one, their bodies dropping into the graves.