By John W. Osborn, Jr.

Thailand was perhaps the least known, though surely more scenic and exotic, covert battleground of World War II. For one American, it would be the adventure of a lifetime already filled with adventure, for another mental anguish in the dark. A British agent was almost killed by his briefcase. A rebel would find himself a royal stand-in, then a resister. In the end, the Japanese would be so oblivious to reality they were dancing just two days before their doom.

A revolution in 1932 had stripped the Thai monarchy of its absolute power, though the substitute would prove worse—a Fascist-leaning military strongman, Colonel Pribul Songgram. Becoming premier in 1940, Pribul styled himself “Leader,” scapegoated the Chinese minority the way Hitler did the Jews, and, determined to break Great Britain’s stranglehold on trade, ominously moved Thailand into the political orbit of Japan.

London was worried enough by the summer of 1941 to suggest a joint effort with Washington to wean Pribul from Tokyo. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull by then believed that the effort would be hopeless. He believed that Thailand was already in the clutches of Japan.

Appealing to America for Support

Japanese control became official on the day Pearl Harbor was attacked, December 7, 1941. As 20,000 Japanese troops were landing uninvited on Thailand’s coast, the Japanese ambassador in Bangkok was dictating to Pribul and the Thai cabinet the terms of passage for Japanese troops to transit Thailand and attack the British in Burma, an alliance between Japan and Thailand, and declarations of war against Great Britain and the United States.

In Washington, the Thai minister had to make it official by handing notification to Hull. When that moment came, though, with tears in his eyes, he refused: “I am keeping the declaration in my pocket because I am convinced it does not reflect the will of the Thai people. With American help, I propose to prove it,” he declared.

The U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency) soon had more immediate concerns regarding Thailand than the country’s liberation, however. “Right now Siam is the biggest information blind spot in the Far East,” the agent being sent there, Colonel Nicol Smith, was briefed. “General Stilwell is fighting a tough campaign in Burma, and he wants to know how many Thais are under arms and whether they really want to fight for the Japs. The Army Air Forces want to know where the most important Jap installations are so they can bomb them. General Chennault wants to know where prison camps are and whether some of his fliers downed over Siam can be rescued. The State Department wants to know to what extent the present government represents the will of the Thai people.”

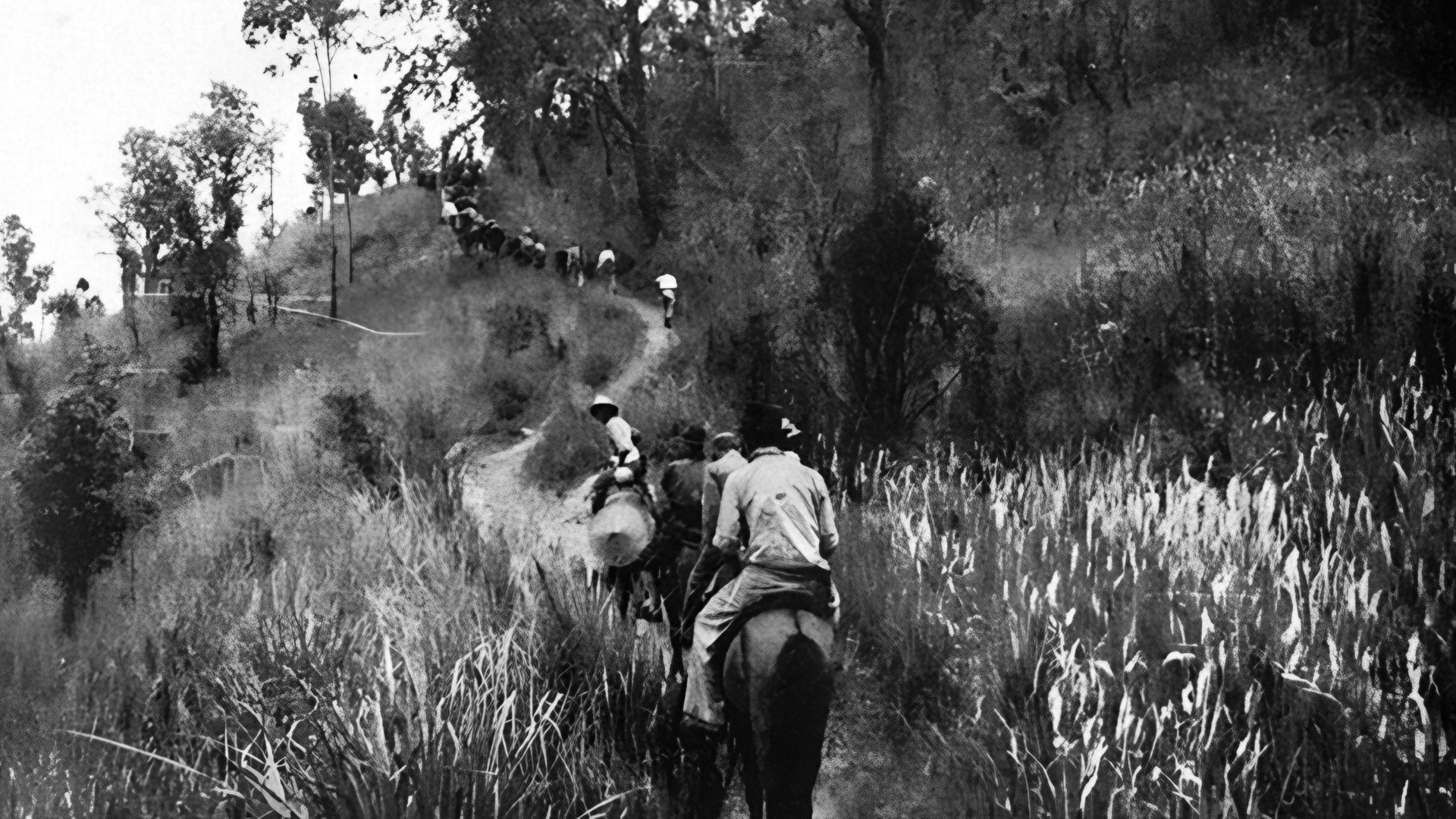

Colonel Smith had been adventuring around the world since paddling the length of the Danube River in a canoe when only 17 years of age. He had been a captive of South Seas islanders before escaping, was shipwrecked, spent time among the inmates of the Devil’s Island prison colony (as a visitor), went up South America’s River of Death where a tribe adopted him, and traveled the length of the Burma Road. He was already well acquainted with the wilds of China and covert intelligence work, having just returned from a year inside Vichy France. With 21 American-educated Thais recruited by the Thai Minister to the United States, he set sail for Thailand from Baltimore via the Panama Canal on March 15, 1943.

Making Contact With Bangkok

While Smith spent the next year training in India with his Thais, then trekking with them across China, the postwar future of Thailand was developing into a bone of contention between the Allies. Washington regarded Thailand as a victim of Japanese aggression to be treated as a liberated country, while London had answered Thailand’s declaration of war with one of its own in February 1942 and was making plain its intention to place Thailand under indefinite occupation.

The dispute extended further to the intelligence services. Britain’s counterpart to the OSS, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), was planning to send its own Thais back into the country. Meanwhile, both agencies would find their Thai operations obstructed by the notorious head of Chinese intelligence, “the Chinese Himmler,” General Tai Li.

When Smith finally reached the Indochina border, the promised assistance from Tai Li failed to materialize, and the first two Thais he sent into the country were killed by the Japanese. Finally, a Chinese Catholic priest, whom Smith promised $1,000 to build a new church, agreed to lead a new quartet of agents during the monsoon season when they would be least expected.

Almost three months passed anxiously for Smith, as the SOE’s own Thais reached Bangkok first and he was warned that the OSS was about to cancel his mission. Then, finally, on October 5, 1944, came the first broadcast by the OSS Thais from inside Bangkok. Smith and some officers were dejectedly killing time with one more nightly card game when another officer rushed in to announce contact had finally been made.

“For a moment we were all too stunned to speak,” Smith recalled in his postwar memoir Into Siam: Underground Kingdom. “Then, as if we were one, the entire group leaped from the table scattering cards and chips on the floor, and rushed for the radio shack…. The tap, tap, tap was sounded over and over again, little by little, groups took tangible shape on paper. Never had anything looked so good to me as did those ever-increasing letters of the alphabet.”

A Flood of Detailed Intelligence

The Thais were broadcasting from inside the national police headquarters, but they were not prisoners—the chief was a major figure in the resistance movement. As Smith was to later jubilantly write, “The two hundred and twenty thousand square miles of Thailand was no longer an information blackout. A lamp had been lighted in the capital of Siam, more than five hundred miles to the south, and we knew it would be shining ever brighter until the end of the war and the return of freedom.…

“Requests for information came thick and fast. Our intelligence became increasingly detailed.”

Information was exchanged daily between Bangkok and the Free Thai legation and the State Department in Washington.

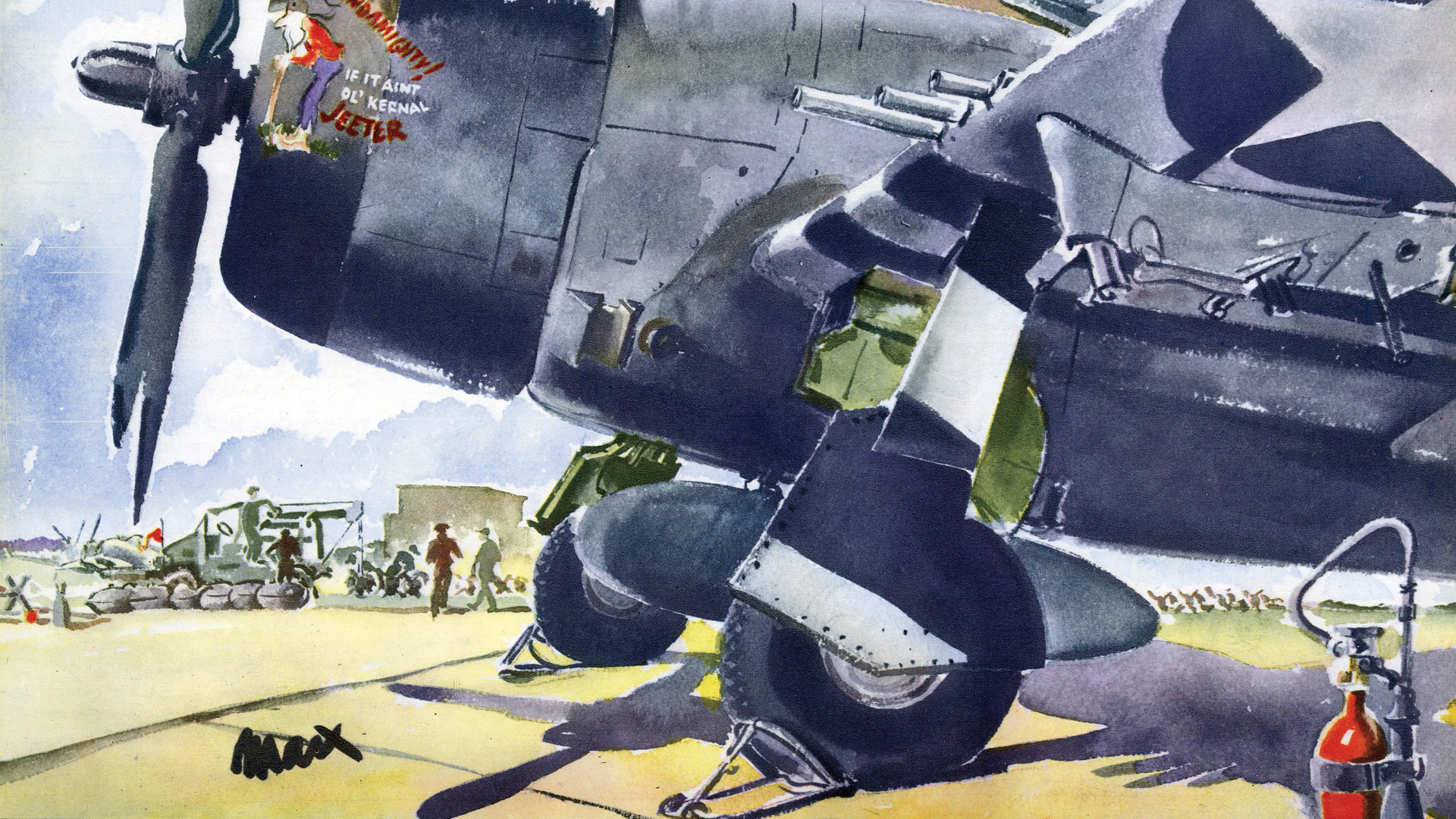

“We were giving twenty-four-hour weather reports and designating more and more plane targets. We were able to inform General [Albert C.] Wedemeyer about Jap troop movements across Siam to Burma. We told the Air Force which side of the [Bangkok] airport the Thais were using, and which side the Japs. Every branch of the armed services and every Allied government agency pressed us for answers to vital questions. Replies came back from inside Jap-held Thailand with remarkable conciseness.”

The Free Thais were followed by American and British agents parachuted in or landed on hidden airstrips in the jungle. The OSS was also active along Thailand’s coast, dropping off and then picking up reconnaissance units by PT boat. “It was a river war like the movie Apocalypse Now,” one boat captain remembered. “I think it was the most fun I had in my life.”

Some agents found the secret service in Thailand less enjoyable. The first American radio operator in Bangkok, after two months of never leaving the darkened room he broadcasted from, suffered a complete mental breakdown and had to be evacuated to the coast. The head of the SOE mission, Colonel David Smiley, had the James Bond-like briefcase designed to burn documents inside in the event of capture suddenly explode in his hand, drenching him in flaming liquid. After a week of agony, covered in burns with no medical treatment available, he was flown out to recover and eventually return to Thailand.

The Operation’s Guerrilla Wing

Besides information, the OSS and SOE worked to organize resistance against the 50,000-strong Japanese occupation force. “There was a reception for every drop,” one of the SOE Thais recalled. “Transport, food, shelter, and cover stories were provided…. As practically all the government official and the civilian population were with us there was no hide-and-seek with the Japanese counterespionage.

“Once established in our respective areas, all we had to do was state what we required: the categories of men for the different types of work and the number of recruits we required. The underground responded promptly. Guerrilla and subversive activities would have been well-nigh impossible had it not been for the organization inside Siam. Without local help we would not have lasted long.”

Guerrilla bands totaling 10,000 members were founded. But the China-Burma-India Theater was the end of the line in Allied priority for supplies, and Thailand the end inside that line. Less than 200 tons of arms and ammunition for the resistance were eventually airdropped or flown in.

Codename Ruth

The Americans continued to operate out of the police headquarters in Bangkok, the British, even more improbably, from the office of the commandant of the main internment camp for Western civilians. On July 13, 1945, it was finally Colonel Nicol Smith’s turn to head to the capital to meet the leader of the resistance, codenamed Ruth, and inform him to refrain from a general uprising until the British offensive to liberate Malaya scheduled for November 1945 had commenced.

Smith flew from liberated Burma to a secret airstrip inside Thailand and from there in a Thai Air Force transport to Bangkok’s main airfield. Upon landing he and his companion got a shock when Japanese ground crewmen pushed an aircraft of their own just five yards past them!

“Lloyd and I were flat on our stomachs, our faces so close together our noses touched,” Smith recalled. “The sweat rolled off my forehead. I could feel drops pouring down my neck.”

From there they were driven to the Royal Palace, of all places, to meet Ruth.

Ruth was no less than Pridi Phanomyong, regent for the absent boy-king Ananda Mahidol, who was at boarding school in Switzerland when the Japanese took over. Ironically, Pridi had been a leader in the revolution that reduced the monarchy to ceremonial status and was later fired by Premier Pribul from the post of minister of finance for opposing the Japanese and politically sidelined, it appeared, in the regency.

Then, in July 1944, the Thai Parliament forced Pribul to resign. There was no reaction from the Japanese, and Pridi was in control of the government. “A double life is not an easy one,” he told Smith. “By day I sit in my palace and pretend to busy myself with the affairs of His Majesty. In reality the entire time is taken up with problems of the underground—how we are going to get more guerrillas; how we are going to feed the ones we already have; how we can, without suspicion, replace governors from provinces where we are putting in American camps so that we may always have one of the men of the underground in the key position.”

Thailand After the War

That life was about to get even harder. Passing Japanese aircraft had spotted secret landing strips, then ground searches uncovered hidden arms. Pridi denied knowledge but warned Smith to get out. “The Japanese may assassinate me,” he said. “I’m afraid it’s the beginning of the end.”

As Smith was being driven out of town past the biggest hotel in Bangkok, he heard a raucous party going on inside. The driver said the Japanese were celebrating Tokyo’s dismissal of the Potsdam Declaration.

“We couldn’t resist pausing a few moments to watch,” Smith would later write. “The music never stopped. As soon as one orchestra finished, the other began. Around and around the dance floor whirled the Japanese, celebrating the New Order in Southeast Asia—two days before the atomic bomb.”

The bomb saved Pridi and Thailand. The Japanese were so demoralized that the SOE’s David Smiley, recovered from his burns, was able to supervise the disarmament of 10,000 Japanese troops singlehanded.

Pressure from Washington forced the British to sign a peace treaty with Thailand that merely terminated hostilities, such as they had never been, with no occupation. Young King Ananda Mahidol returned, but was found dead at the age of 19 from a gunshot wound. The origin of the fatal shot was never satisfactorily explained. Pridi Phanomyong remained in power until overthrown in 1949 by Pribul Songgram, who would be ousted in turn in 1957.

Ironically, it would be the former Fascist Songgram who made Thailand the ally of the United States in the Korean and Vietnam conflicts.

On Donovan’s left is film Director John Ford, my fathers Commander in WWII. The story was that Donovan had pressed Ford to parachute into Burma, a very unnecessary stunt. USN Chief John S. Barnett was one of Ford’s pallbearers in 1973. Barnett’s cousin, Janice Lewis had been appointed UN Director of Information, Southeast Asia by Secretary General U Thant when i visited her office in Bangkok. I was US Army 91U-20 EENT Specialist at the time.