By William E. Welsh

American militiamen with their lungs heaving, hearts pounding, and eyes bulging with terror ran for their lives as soon as the British and Hessian troops in their bright red and blue uniforms came ashore at Kips Bay on Manhattan Island. No officer, not even General George Washington, who waded on his horse into the river of humanity, could check the retreat of the Patriots. When the enemy began firing in Washington’s direction, his aides compelled him to fall back and join the headlong retreat toward Harlem Heights to the north. “The demons of fear and disorder seemed to take possession of all and everything that day,” said an American private. “Nothing appeared but fright, disgrace, and confusion,” said an American officer.

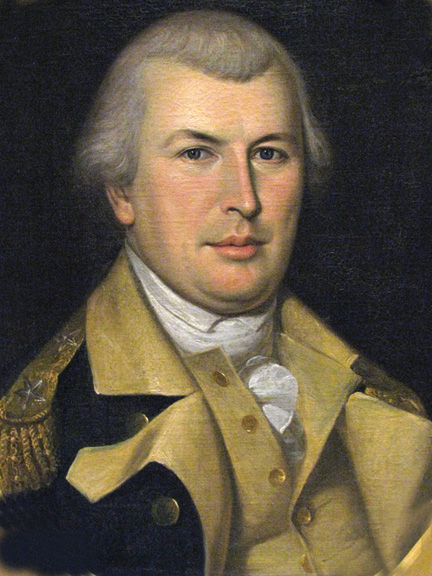

Not a shot was fired in opposition to the British amphibious landing the morning of September 15, 1776, on Manhattan Island, which occurred less than three weeks after the British decisively defeated the Americans in the Battle of Long Island. The officer who had laid out the American defenses on Long Island in April, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, had been stricken with a debilitating fever just days before the August 27 battle and therefore was not directly responsible for the debacle. Even before the British set foot on Manhattan, Washington, Greene, and others were in agreement that the island, surrounded by water, could not be held against the British, whose large fleet controlled not only the bay to the south but also the East and Hudson rivers.

Greene had recovered enough to return to active duty the first week of September. When Washington had solicited the Rhode Island general’s advice about what should be done in regard to the defense of the city, Greene made a harsh recommendation.

“I would burn the city and suburbs,” said Greene, noting that two-thirds of the city’s population was loyal to King George III. “It will deprive the enemy of an opportunity of barracking their whole army together [and] deprive them of a general market. All these advantages would result from the destruction of the city. And not one benefit can arise to us from its preservation.”

Neither Washington nor the Continental Congress was ready to take such a drastic step. Ironically, an accidental fire in the early hours of September 21 burned a quarter of the city, most of which by then was under British occupation. What Greene’s remarks reveal is that he knew that for an underdog to succeed against a more powerful foe it had to take drastic, unpopular steps.

Four years later, on October 14, 1780, Washington appointed Greene to command American forces in the southern colonies following the British victory at Camden. As an independent commander, Greene would have a chance to show what Washington knew all along—that Greene had the fortitude to make difficult decisions. Furthermore, Greene had learned well from serving under Washington that it was best to avoid a general engagement with the British. Instead, the path to American victory in the long war was to wear down the British, giving battle when the enemy’s strength had been substantially compromised.

With the entry of France into the American Revolutionary War on the side of the Americans in February 1778, British control of the waters on the Eastern Seaboard was no longer assured. British commander-in-chief General Henry Clinton decided shortly afterward that rather than continue to wage war from New York he would take advantage of substantial Loyalist support for the war in the southern colonies, particularly in the Carolinas. Clinton believed strong Loyalist support in the southern colonies would enable the British to form a solid base from which to renew efforts to extinguish the rebellion in the rest of the colonies.

The British occupied Savannah, Georgia, on December 29, 1778. Then, after a month and a half siege, Clinton forced Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln on May 12, 1780, to surrender his 5,000-man army, which had been bottled up in Charleston, South Carolina.

The following month, Clinton returned to New York, leaving Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis, a veteran of the battles in New York and New Jersey, to eradicate Patriot resistance in the Carolinas. Although the number of British regulars Cornwallis had was modest compared to the British Army in New York, he was optimistic that he could recruit large numbers of Loyalist militia. To deal with Patriot guerrillas that raided British outposts and threatened British supply lines, Cornwallis created a fast-moving mounted strike force led by the ambitious and ruthless Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton.

Initially things went well for Cornwallis. In one of the first of a number of key small battles in 1780, Cornwallis defeated an American army led by Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates on August 16 for control of the important inland supply center of Camden, South Carolina. Gates, who fled on horseback to save his own hide, proved that he was not worthy of commanding American forces.

While Cornwallis was busy plotting an invasion of North Carolina, he dispatched Major Patrick Ferguson to lead Loyalist militia against bands of Patriots in western South Carolina that threatened Cornwallis’s supply line. Ferguson’s vow to lay waste to the farms of those who did not swear allegiance to George III compelled the so-called over-mountain men from the Blue Ridge Mountains to plot to kill Ferguson. In a bloody clash of Patriot and Loyalist militia on October 7 at King’s Mountain, Ferguson was shot during a vain attempt to rally his men.

The Patriot victory at King’s Mountain had substantial repercussions. First, it resulted in the loss of a Loyalist army that represented one-third of the manpower available to Cornwallis. Second, it forced Cornwallis to delay his planned invasion of North Carolina.

Greene arrived in Charlotte, North Carolina, during the first week of December to take command of the downtrodden American army that Gates left behind. The son of a Rhode Island Quaker, 38-year-old Greene was tall and stocky with striking aristocratic facial features.

Anticipating that Rhode Island would need to contribute significantly to the Patriot cause, Greene had raised a company of militia in 1775. That year Congress appointed a total of 12 generals, one of whom was Greene. He was the youngest and least experienced of the group. By the time Greene arrived in North Carolina, he had substantial administrative and battlefield experience in the Brandywine/Germantown and Monmouth campaigns. Having served as quartermaster and commissary general at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778, he was amply acquainted with the hardships that the Patriots had to endure if they were to prevail over the British.

Greene needed an interim plan to keep Cornwallis occupied while he recruited militia and waited for the arrival of additional regulars from the middle colonies. Greene decided in late December to send Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan, an expert in backcountry warfare, into western South Carolina. Once there, Morgan could recruit militia and harass British outposts.

Cornwallis was not about to let Morgan operate unopposed. Cornwallis sent Tarleton with a fast-moving column of 1,000 men to intercept Morgan. The two forces, which were equally matched, collided on ground of Morgan’s choosing. Morgan selected as his defensive position a meadow known as Cowpens. On the morning of January 17, 1781, Morgan put his militia in two lines to soften up the British and placed his regulars behind the militia in a third line. Morgan deployed companies of rifleman and dragoons on both flanks. Tarleton committed all of his troops to the battle. When the British assaulted Morgan’s main line, they floundered. A bold bayonet attack by Morgan’s continentals routed the British. Nearly all of Tarleton’s army was either killed or captured.

When the disaster at Cowpens occurred, Cornwallis was encamped about 40 miles to the southeast at Turkey Creek. A small number of begrimed survivors arrived during the night and shared news of the disastrous defeat. The British commander desperately wanted revenge. Another large British force under the command of Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie had arrived at Turkey Creek that same day, swelling Cornwallis’s army to 2,550 men.

Two days later the British broke camp. Morgan had not lingered at Cowpens. He had marched swiftly into North Carolina to put as much distance as possible between his force and Cornwallis’s larger one. On January 23, Morgan’s men crossed the Catawba River. Since catching the Americans would be difficult with his cumbersome baggage train, Cornwallis on January 24 ordered his commissary wagons burned. The following day Cornwallis encamped at Ramsour’s Mill on the west side of the Catawba. The river was rising from heavy rains, which delayed Cornwallis’s pursuit.

The weather seemed to be on the side of the Americans as January drew to a close. On January 30, Greene arrived in Morgan’s camp to discuss strategy. The “Fighting Quaker” told Morgan he wanted to continue the American retreat as far as the Dan River, which lay just across the border into Virginia. Morgan argued that it was a risky strategy because Cornwallis might overtake the Americans and force them to fight when they were not ready. But Greene overruled Morgan.

Cornwallis fought his way across the Catawba on January 31. Morgan had left behind Brig. Gen. James Davidson’s North Carolina militia to guard the fords that Cornwallis was likely to use. The British regulars easily overran the militia, and Davidson was slain in the fighting.

Morgan marched swiftly through Salisbury and made it across the Yadkin River with Cornwallis on his heels. Greene, who was following behind Morgan, was desperately trying to rendezvous with Brig. Gen. Isaac Huger’s force, which had been operating independently in eastern South Carolina. Unable to affect a junction of American forces at Salisbury, Greene advised Huger to continue north toward Guilford Courthouse.

Late in the day on February 2, the Americans crossed the flooded Yadkin River in rowboats that Greene had arranged for ahead of time. While Cornwallis waited for the Yadkin River to drop so his army could cross on foot, Greene led his army to Guilford Courthouse where it rendezvoused with Huger’s 1,500-man force. Although at that point Greene had enough men to meet Cornwallis on near equal terms, he stuck with his plan to march to the Dan River.

Cornwallis ordered Tarleton to take his remaining dragoons and try to catch up to Greene. Although Tarleton would not be strong enough to attack the American column alone, he could keep Cornwallis informed of its movements. Greene dispatched Lt. Col. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee’s cavalry to drive off Tarleton.

Greene needed a strong commander for a rear guard to hold off the British while the Americans crossed the Dan River. Although Greene gave first consideration to Morgan, the stalwart frontiersman’s physical condition was deteriorating, and he was allowed to leave the army.

Greene had devised a plan to mislead the British in order to buy time for the Americans to cross the Dan River safely. Greene entrusted command of the rear guard, which would consist of a 600-man light corps, to Colonel William Washington. He told Washington to march toward the upper reaches of the Dan River. If the plan worked, the British would follow Washington while Greene led the main body of the American army to the lower Dan, where it might cross by boat at Boyd’s Ferry without being attacked by the British. On February 13, Greene’s army safely crossed the lower Dan. To make the most of a bad situation, Cornwallis issued a proclamation from Hillsborough, North Carolina, stating that the British had driven the Americans out of the Carolinas and secured them for George III.

Because of the continuing erosion of his militia, Greene’s force had shrunk to about 1,500 by the time he crossed the Dan River. To meet Cornwallis in a set-piece battle, he would need an infusion of both regulars and militia. In the meantime, he sent Lee’s Legion and Washington’s Light Corps south of the Dan River in late February to harass the British. Lee achieved a key success on February 25 when his dragoons defeated 400 Loyalist militia under Colonel John Pyle in the Battle of Haw River.

Greene’s main force crossed to the south side of the Dan River in late February. Greene was still waiting for reinforcements from Virginia, and therefore he purposely kept his forces at what he believed was a safe distance from Cornwallis’s army. But Tarleton believed Greene’s advance units were vulnerable.

Acting on Tarleton’s intelligence, on March 6 Cornwallis ordered Lt. Col. James Webster, whose brigade included two regiments of veteran British foot soldiers, to launch a surprise attack against the vulnerable American units south of Weitzel’s Mill on Reedy Fork Creek. As often happened in the campaign, the British lost the element of surprise when their advance was reported by an American patrol.

The exposed American units marched rapidly north to Weitzel’s Mill. They barely made it across the creek before the British arrived. The American force, which consisted of Brig. Gen. William Campbell’s Virginia Rifle Regiment, Colonel Otho Williams’ Maryland Brigade, and Lee’s Legion, fanned out to cover three fords in close proximity to the mill.

In a short but sharp skirmish in which the smoke from the muskets mixed with morning fog in the creek valley making it difficult for either side to clearly see the enemy, Webster sent the 33rd Regiment of Foot to force a crossing at Main Ford (the middle crossing) and the 23rd Regiment of Foot, also known as the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, to fight its way across Horse Ford (the eastern crossing). The initial assault of the 33rd Regiment was repulsed, but Webster personally led the second attack, which was successful. Once the British had gained a foothold on the north bank, the Americans continued their withdrawal. A running battle occurred for five miles before the British stopped their attack. Each side lost about 30 men.

A standoff occurred in the first half of March with Cornwallis encamped south of Guilford Courthouse at Deep River Friends Meeting House and Greene bivouacked north of the courthouse at Speedwell’s Iron Works on Troublesome Creek. During that time, Greene’s ranks swelled with the addition of 400 newly recruited regulars from Maryland. He also gained substantial numbers of eager militia, including 600 Virginia militiamen under Brig. Gen. Robert Lawson and two brigades of North Carolina militia totaling 1,000 men led by Brig. Gens. John Butler and Thomas Eaton. Greene decided that the new recruits to his army would give him good odds in a set-piece battle against Cornwallis’ 1,900-strong army, so on March 14 he marched his 4,500 Americans south to preselected positions at Guilford Courthouse.

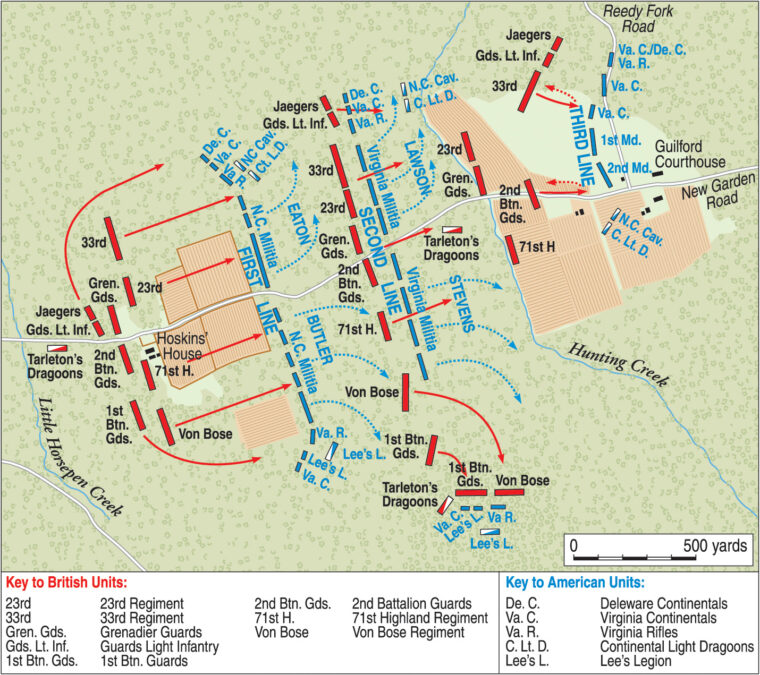

Guilford Courthouse was located about 15 miles due west of Weitzel’s Mill. The courthouse was situated on a low hill slightly less than 11/2 miles east of Little Horsepen Creek. On the east bank of the creek were farm fields, but a belt of woods separated the fields near the creek from other fields surrounding the courthouse. The first clearing was about 800 yards wide, the belt of woods another 800 yards, and the distance from the east edge of the woods to the courthouse another 800 yards. The farm fields between the woods and the hill on which the courthouse sat were located in a shallow vale.

On March 14, Greene’s army struck camp and marched about 20 miles south to Guilford Courthouse. The “Fighting Quaker” was concerned that Cornwallis might learn of his advance and attempt a surprise attack that night, so he ordered Lee to take his Legion and patrol west on New Garden Road. To bolster Lee’s Legion, he ordered Campbell to send 100 Virginia riflemen to accompany Lee. The savvy American cavalry commander set up a blocking position about 11/2 miles west of Little Horsepen Creek. In addition, Lee detailed Lieutenant James Heard to lead a patrol to watch Cornwallis’s camp and send word once Cornwallis began his march to Guilford Courthouse to seek the battle for which he was so badly yearning.

On the evening of March 14, Cornwallis’s scouts informed him that the Americans were 12 miles away from the British camp at Guilford Courthouse. As expected, the British broke camp at 4 am. Heard sent word to Lee, who passed the information along to Greene. When Greene received the news, he sent orders to Lee to contest the British advance. Greene wanted to fight the British in full daylight because he believed the highly disciplined British regulars would have a clear advantage in a predawn battle.

Lee decided to spring an ambush on his archrival, Tarleton. Light Horse Harry told two-thirds of his troops to conceal themselves behind fences lining the road. One troop of cavalry remained in the road. Lee’s instructions to the hidden cavalrymen and infantry were to fall on the British once they became heavily engaged with the single troop of American cavalry.

At about 4:45 am, Tarleton’s cavalry attacked Lee’s cavalry. Slashing sabers rang out in the gray light of dawn as each side sought to gain an advantage. When the British drove back the cavalry in the road, the concealed American troops joined the skirmish, striking Tarleton in both flanks. Shots rang out as the Virginia riflemen attempted to drop some of the British from their saddles. In the melee Tarleton was shot in the hand, which meant that he would have only one hand with which to guide his horse throughout the long day ahead. The British suffered 30 men killed, wounded, or captured in the sharp skirmish. Lee’s men regained the ground they had lost, but they were forced to fall back when Webster’s Royal Welsh Fusiliers arrived and reinforced Tarleton.

Since Morgan’s deployment of his army in three lines at Cowpens had laid the foundation for an American victory, Greene decided to position his troops similarly. He intended to deploy his green militia in the first line, his veteran militia in the second line, and his regulars in the third line.

Eaton’s Brigade would hold the right, and Butler’s Brigade would hold the left in the first line. The North Carolinians fanned out behind split rail fences along the eastern edge of the farmland nearest to Little Horsepen Creek. To bolster the militia, Greene ordered Captain Anthony Singleton of the First Continental Artillery to deploy his two 6-pounders in the center of the line astride New Garden Road.

Greene also deployed Washington’s Legion, Colonel Thomas Lynch’s Virginia Rifle Regiment, and Captain Robert Kirkwood’s company of Delaware regulars to anchor the extreme right of the first line. Similarly, Greene ordered Lee’s Legion and Campbell’s Virginia Rifle Regiment to hold the extreme left of the first line. As for the militia in the center, the general idea was that they were to fire three volleys at the enemy and then fall back. Likewise, the veteran units on the American flanks also were to fall back and maintain their respective positions to prevent the British from outflanking any of the American lines.

Greene ordered the Virginia militia to form a second line in the woods about 800 yards behind the first line. The “Fighting Quaker” ordered Stevens’s and Lawson’s Brigades of veteran Virginia militia to form, respectively, the left and right sections of the second line. They also were given permission to retire after firing three volleys. Greene’s intention was that the two lines of militia would soften and tire the British so that they would be too weak to break the third line.

The third line, which deployed on the east side of the vale separating the woods from the courthouse, was about 500 yards behind the second line. Unlike the first two lines, the right and left wings of which lay directly astride the New Garden Road, the third line was entirely north of the New Garden Road on the slope of a hill with the left flank positioned to follow the contour of the low ridge. Greene ordered Williams’s Maryland brigade to form up on the left and Colonel Isaac Huger’s Virginia Brigade to take up a position on the right. The Continental regiments from left to right were Lt. Col. Benjamin Ford’s Second Maryland Regiment, Colonel John Gunby’s First Maryland Regiment, Lt. Col. Samuel Hawes’s 5th Virginia Regiment, and Lt. Col. John Green’s 4th Virginia Regiment.

Cornwallis was fortunate to have competent and tenacious subordinate commanders. Although the cavalry skirmish was over shortly after daybreak, the British commander waited most of the morning for his army to arrive at the battlefield. The men from North Carolina in the front line of the American army listened nervously to the sound of fifes and drums throughout the latter part of the morning, signaling the approach of the main body of Cornwallis’s army on the New Garden Road. The natural thing to do seemed to be to crouch low behind the split rail fence for protection and await the awful specter of battle.

Shortly after noon the British marched across Little Horsepen Creek and switched from column into line of battle on the opposite side of the farm fields from the North Carolina militia. Cornwallis entrusted his left wing to Webster and his right wing to Maj. Gen. Alexander Leslie. Webster’s left wing comprised the 33rd Regiment of Foot and Lt. Col. Nesbitt Balfour’s Royal Welsh Fusiliers, which took up positions on the left and right, respectively, north of the New Garden Road. Forming a second line behind them were Colonel James Stewart’s Second Guards Battalion and the Grenadier Detachment from the Foot Guards.

Forming the front line of Leslie’s wing were Lt. Col. Duncan McPherson’s Second Battalion of the 71st Highlanders in their distinctive blue bonnets on the left and the blue-uniformed Hessians of Johann Du Buy’s Von Bose Regiment on the right. Supporting them in a second line was Lt. Col. Chapel Norton’s First Battalion of the Foot Guards. As for the reserve, it comprised Tarleton’s Legion, the Hessian jaegers, and the Light Infantry Detachment of the Foot Guards.

Cornwallis maintained control of these units so that he could dispatch them where needed as the battle progressed. Assisting Cornwallis in directing units into the battle was Brig. Gen. Charles O’Hara, who commanded the Guards Brigade. At about 12:30 pm, Cornwallis ordered Lieutenant John MacLeod to open up on the Americans with his 3-pounders. Singleton responded with his larger guns, but the action did nothing more than signal that the time had come to decide by force of arms which side would control North Carolina.

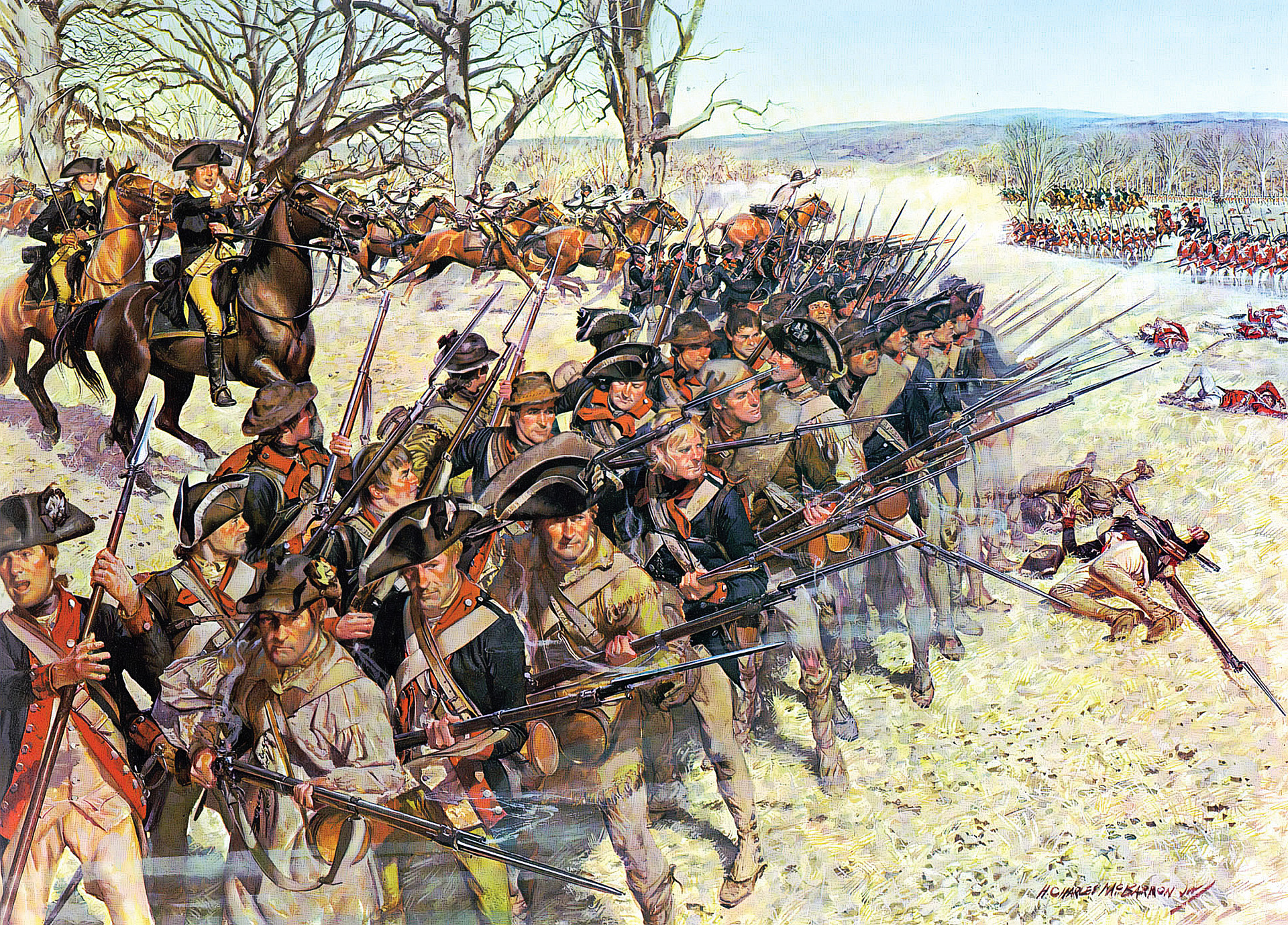

Cornwallis studied the American position behind the split rail fence through his field glasses. Greene’s tactics did not impress him. He discerned that Greene had probably deployed multiple lines to blunt his attack, and he also knew that the militia would scatter when threatened with a bayonet charge. They simply were no match for the well-drilled and unshakeable British regulars. At 1 pm, Cornwallis gave the order for his two wings to advance. The British and Hessians marched with muskets angled slightly upward and bayonets fixed across the stubble fields toward the Americans. When the British were within 140 yards, the North Carolinians stood up and fired their first volley. Some British and Hessians fell to the ground. Clouds of smoke from the guns made it difficult for the Americans to see what damage they had inflicted. Within the British ranks, men from the second rank quickly stepped forward to plug the gaps created by the American volley, and the British continued their advance with an impressive degree of precision.

When the British came to within 50 yards of the American front line, they stood and fired a volley, tearing large gaps in the American line. Then the British charged. “C’mon my brave Fusiliers!” shouted Webster as the British ranks surged forward. It was more than the North Carolinians could take. All of the men in Butler’s Brigade on the American left ran for their lives, throwing away packs, canteens, and muskets as they sought safety in the woods behind them. A portion of Eaton’s Brigade remained in the fight by falling back obliquely on the veteran companies commanded by Washington on the American right flank. The battle was well under way, and it promised to be a sanguinary affair as the opening action showed. Of the fighting, Captain Roger Lamb of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers wrote, “Dreadful was the havoc on both sides.”

As soon as the North Carolinians fled, the American flanking units began pouring steady musket and rifle fire into the outside regiments of both wings as they entered the woods. The 33rd Foot and the Hessians on the left and right, respectively, turned to respond to the flankers. This greatly slowed the advance east of the outside regiments, so Cornwallis ordered two units from the reserve to join the fight against the American flanking forces to free up the outside regiments. The British commander ordered the Hessian jaegers to join the left wing and instructed the light infantry of the Foot Guards to aid the right wing.

Cornwallis also was deeply concerned that his inside regiments, which had lost many men to the single volley by the North Carolinians, would need additional support. He therefore sent the 2nd Battalion of the Foot Guards and the Grenadier Detachment of the Guards to join the center of the British line by falling in on the right flank of Webster’s Royal Welsh Fusiliers. This meant that the only remaining reserve unit was Tarleton’s Legion. It was important to hold back the dragoons in case they were needed to cover a partial or full retreat.

One part of the battle did not go as planned by either Cornwallis or Greene. Instead of falling back to the second line, Lee decided on his own initiative to withdraw his legion southeast to a small knoll in the woods about three-quarters of a mile from New Garden Road. Lee’s intention probably was to weaken the British army’s attack against the second line of militia. The First Battalion of the Foot Guards and most of Von Bose’s Regiment took the bait and pursued Lee. What developed as a result was an isolated battle involving about 300 men on each side.

Greene believed the Virginia militia in the woods would fare better than the North Carolinians not only because of their experience, but also because of the obstacles the forest presented to the British battle line. Cornwallis’s regulars were forced to fight in small groups to navigate around the trees and undergrowth. As a result, they were not able to inflict the shock of a massed bayonet charge by an entire regiment but instead could bring the bayonet to bear only in groups or singly. What is more, the losses the North Carolinians had inflicted on the British and the American flank attacks sapped the strength of the units in the middle of Cornwallis’s line.

The British struck Greene’s second line at about 2 pm. The 71st Highlanders were heavily outnumbered against Stevens’s Brigade, which held the left of the American second line. But Webster’s Brigade, augmented by the smaller reserve units in the center, had much greater success against Lawson’s Brigade on the American right. As soon as they struck Lawson’s broken line in the woods, the Welsh Fusiliers were able to successfully penetrate it. At the same time, the jaegers and light infantry attacked Lawson’s left flank. Lawson’s militiamen fired a few scattered shots at the British, but most of them fled in panic when they realized that the British were behind them. The militia “dispersed like a flock of sheep frightened by dogs,” wrote Major St. George Tucker, an officer in Lawson’s Brigade.

Stevens’s Brigade made a better show of things. They held their ground initially against the British. Firing from behind trees, the Virginia militiamen felled a number of British with their fire. “Posted in the woods and covering themselves with trees, [Stevens’s Brigade] kept up for a considerable time a galling fire, which did great execution,” wrote Charles Stedman, a British staff officer. The 71st Highlanders, like the regulars of Webster’s Brigade, used a tactic in which some members of a group fixed the enemy in place with their fire while the remainder flanked the enemy and charged them with their bayonets.

While the regiments closest to New Garden Road were busy fighting the Virginia militia, the First Battalion of the Foot Guards and the Von Bose Regiment of Hessians pressed their attack on Lee’s Legion and Campbell’s riflemen to the south. Lee’s Legion initially had the upper hand when it outflanked Norton’s Guards, but a counterattack by Du Buy’s Hessians stabilized the situation. At that point, the British launched an all-out assault to capture the knoll. They managed to capture it briefly, but a subsequent counterattack by the Americans successfully recaptured it. The Americans would retain the upper hand for most of the small isolated battle until Cornwallis sent Tarleton’s dragoons to assist the British and Hessians, both of whom were at a disadvantage in the forest against the Americans.

Between 2:30 and 3 pm, sporadic fighting continued in the woods as the Virginia militia fell back toward the safety of Greene’s third line. Greene’s tactic of wearing down the British had succeeded, but the day would be decided when regulars from both sides met each other in the vale west of the courthouse.

The left wing of the Continental Army regiments in the third line consisted of the 2nd Maryland, Captain Ebenezer Finley’s Detachment of Continental Artillery, and the 1st Maryland. The right wing was composed of the 5th Virginia and 4th Virginia. When Lynch’s Virginia riflemen and Kirkwood’s company of Delaware regulars reached the third line, they took up a position on the right of the 4th Virginia. Following on the heels of those infantry units that had fallen back steadily from their original deployment on the right flank of the first line were Washington’s dragoons. Washington led his dragoons south through the vale to take up a position in the farm fields on the extreme left flank to compensate for the absence of Lee’s Legion. It was a sound decision on Washington’s part because it gave his horsemen more room to maneuver than if they had stayed in the woods on the extreme right flank.

The first units to reach the vale were the 33rd Foot, the jaegers, and the light infantry detachment of the Guards. Webster immediately led them in an attack at 3 pm against the two Virginia regiments on the American right. When the British and Hessians, who were advancing with bayonets, came to within 40 yards of the American line, the Continental officers gave the order to fire. The first volley completely shattered the assault, and the attackers fell back to the safety of the tree line on the west side of the vale. Webster was among the wounded. He had been shot badly enough in the knee to require assistance to avoid capture.

As the 33rd Foot and its supporting units were retreating, the 2nd Guards Battalion emerged from the woods. Their commander, Lt. Col. James Stewart, also attacked immediately. The 2nd Guards had emerged from the wood on the right flank of the 33rd Foot, and they advanced with fixed bayonets toward Ford’s 2nd Maryland Regiment. Stewart had unwittingly chosen a good place to strike the Continental line because the 2nd Maryland was a green unit and thus as unsteady as a militia unit. The men of the 2nd Maryland shamefully fled into the woods behind them. In so doing, they left Finley’s two 6-pounders unprotected, and the Guards swarmed over them.

The fate of the Continental line hung in the balance. If Cornwallis and his subordinates could exploit the gap in Greene’s line, they might just destroy the American army piece by piece. Seeing the disaster that was looming over the battlefield, Washington ordered his dragoons to draw their sabers and charge the 2nd Guards. They rode north and began assailing them on the right flank to buy time for the remaining Continental regiments to react to the unfolding threat.

Gunby, the commander of the 1st Maryland, had been preoccupied with events on his front and had failed to realize that the 2nd Maryland had been routed. When he became aware of the crisis, he ordered his men to change front to the south. The Guards saw an American regiment advancing on them and turned to meet the threat. The two sides poured volleys into each other at point-blank range. “They appeared so near that the blazes from the muzzles of their guns seemed to meet,” wrote Lt. Col. John Howard of the 1st Maryland. Then both sides fell on each other in desperate hand-to-hand fighting. The British volley killed Gunby’s mount, and he required assistance to get out from under it. In the meantime, Washington’s dragoons continued harassing the Guards. The Marylanders repeatedly charged the Guards, who by that time had begun to suffer substantial losses. After the bloody melee, the Guards fell back, and Gunby’s men were able to recover the two 6-pounders. Gunby’s prompt action and the pluck of his men restored the Continental line for the time being.

By that time, Cornwallis had arrived on the field. Although the 2nd Guards had not entirely exited the vale, Cornwallis made the cold-hearted decision to order the British artillery to fire despite the certainty that many Guards would be slain in addition to the men of the 2nd Maryland. O’Hara, who had been hit twice and was prone, implored Cornwallis not to fire until all of the Guards had made it to the west side of the vale, but Cornwallis ordered Lieutenant John MacLeod to load his two 3-pounders with canister and fire on the Americans. Of the remaining Guards, about half were killed. But Cornwallis’s plan had its desired effect in that Washington’s dragoons rode to safety and the 2nd Maryland fell back to the east side of the vale.

The British were ready to launch a fresh attack at 3:30 pm when the 71st Highlanders and 23rd Fusiliers, both of which had been mopping up against the Virginia militia, emerged from the woods into the vale. Just as they were preparing to attack the vulnerable American left flank, Greene issued orders for his Continental regiments to attempt to break off the fight and retreat east. His rationale was that he had bled the British units substantially and that he intended to preserve the bulk of his army to fight another day. Greene ordered the 4th Virginia to serve as the rear guard during the retreat. To the south, Lee managed to extract his infantry and cavalry from the fight, but in so doing selfishly made no effort to help Campbell break off from the fight at the knoll. This resulted in substantial losses to Campbell’s regiment as Tarleton’s dragoons rode them down and either killed them or took them prisoner.

When Cornwallis realized the Americans were quitting the fight, he decided not to pursue them because most of his units were badly cut up. American losses were about 80 killed and 185 wounded. Of the 1,050 American missing, 885 were militia who promptly went home. The British had lost 93 killed, 413 wounded, and 26 missing. After the battle, Cornwallis had only about 1,400 men to continue his campaign.

Cornwallis led his troops toward the coast. His British and Hessians raided parts of southeastern Virginia and eventually bivouacked at Yorktown in August to await resupply. On September 5, a French fleet successfully blocked a British fleet from reaching Cornwallis.

Cornwallis’s choice of position had proved to be a major strategic blunder. American and French armies, which were well supported by the French Navy, easily bottled up Cornwallis on the Virginia peninsula. Just seven months after the pitched battle at Guilford Courthouse, on October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered his British army to a victorious General George Washington. The long war for American independence was effectively over.

Join The Conversation

Comments