By Gary Mcintosh

The Fletcher-class destroyer was one of the finest, most versatile warships of World War II. More than 170 of them were built, a figure that far exceeds the total of any other type of warship of the era. From 1943 until the end of the war, Fletchers participated in virtually ever campaign in the Pacific.

The U.S. Navy was justifiably proud of the design; even its replacement, the Sumner-class, was visually similar. The Navy was not averse to experimenting with the design, however, and chose it as the experimental platform for one of the most unusual modifications ever made to a destroyer when it added a seaplane to a handful of ships that were under construction.

The Idea to Equip Destroyers With Sea Planes

The idea was not entirely new. The U.S. Navy had toyed with the idea of mounting a seaplane aboard a destroyer as early as 1923, and chose the USS Charles Ausburn as the experimental platform. On August 29, 1923, at Hampton Roads, Virginia, and with assistance of the Naval Air Station and a crew from the aircraft carrier USS Langley, the plane was mounted aboard the destroyer.

On September 1, 1923, the Charles Ausburn steamed from Hampton Roads for experimental operations and battle practice. The plane would be lowered to the surface for takeoff and then hoisted back to its perch near the bow. The experiment was short-lived, and the plane was soon removed.

The idea apparently lay dormant for a few years but was never completely forgotten. In 1940, the four-piper destroyer Noa was fitted with a boom and an XSOC-1 seaplane. The airplane was lowered into the water, where it would make a conventional run to become airborne. During 1940, the Noa conducted several operations with the floatplane, apparently satisfactorily enough that the Navy Department decided to mount seaplanes with more sophisticated launching methods aboard some of the its other destroyers.

On May 27, 1940, Secretary of the Navy Charles Edison directed that six destroyers of the new Fletcher class be equipped with a catapult-launched floatplane and all necessary components to make it operable. An official Navy document, BuShips Drawing 305055, approved on September 12, 1940, was drawn to include the modifications necessary to mount the plane aft of the superstructure between gun mounts 53 and 54. The plane and its equipment would replace a 5-inch gun mount, a torpedo tube mount capable of launching five torpedoes, two twin 40mm guns and their fire directors, and three 20mm guns. Concerned about the possible consequences of “dive bombers approaching from astern” created by the loss of most of its aft armament, the Bureau of Ordnance requested that “the maximum number of machine guns also be mounted aft for protection.”

The Bureau of Ordnance was not the only department that viewed the proposal with a lack of enthusiasm. Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, also was concerned about the loss of gun and torpedo firepower and suggested the design order be rescinded. The Bureau of Aeronautics voiced its opinion that “the advantages to be gained from the necessarily limited operation of the aircraft do not warrant the necessary sacrifice of other features.” Finally, the Bureau of War Planning added, “The price necessarily paid in loss of other valuable military characteristics is unjustifiably great.” Despite their objections and concerns, construction was begun on the first of the catapult-equipped destroyers.

Converting the Destroyers

The ships chosen for the modifications were the USS Hutchins, Pringle, Stanly, Stevens, Halford, and Leutze. The Pringle, Stanly, and Stevens were all built at Charleston, South Carolina. The Hutchins was built at the Boston Navy Yard, and the Halford and Leutze were built at the Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Washington. There is some disagreement about how many of these ships were actually built with the modifications with some historians stating that only three of the ships were built and others insisting that five were. All agree that modifications to the Leutze were cancelled before the conversion began. There is no doubt that the Pringle, Halford, and Stevens were built with the modifications and references mention that the Stanly’s seaplane catapult was removed around December 30, 1942. There is no record of the Stanly ever using the catapult. Evidence is even less convincing that the Hutchins was constructed with the equipment; the ship’s official history does not mention the catapult or floatplane at all.

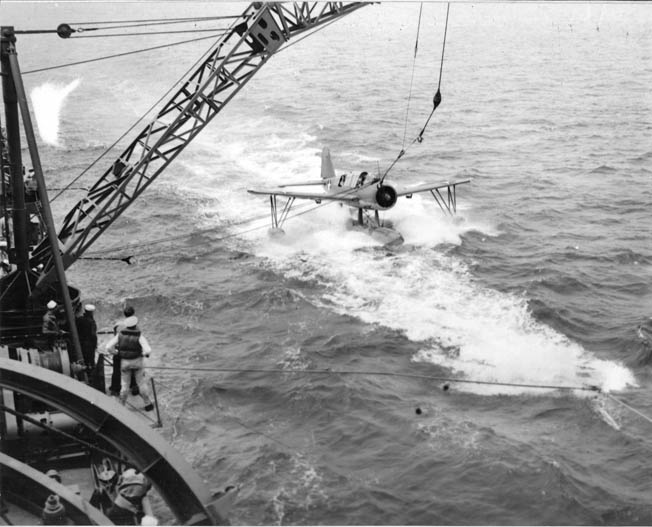

The plans called for a rotating catapult similar to those aboard cruisers and battleships. The catapult was rotated to the ship’s starboard side to launch the plane and a derrick-hoist mounted on the port side was used to recover the plane. When not in use, the hoist was stowed on the deck.

A 1,780-gallon tank for aviation fuel was placed below deck aft of the superstructure. The huge tank was surrounded by a cofferdam filled with carbon dioxide as a safety measure. A fuel line ran from the tank along the port side of the ship to the plane for fueling. A compartment aboard the ships provided storage for tools and spare parts.

The magazine normally used for the 5-inch gun was used to store the bombs and depth charges carried by the plane. The 5-inch gun mount base and the ammunition hoists were left in place, apparently to facilitate the conversion to the conventional Fletcher design in the event the seaplane idea did not work.

The Vought OS2U Kingfisher Scout Plane

The plane selected for use aboard the Fletchers was the Vought OS2U Kingfisher scout/ observation plane with a top speed of only 125 knots. In theory, it was to be used for scouting, spotting, and antisubmarine warfare when the destroyers were operating without heavier units that would normally provide air support. In addition to its regular crew, each destroyer would carry a pilot, a radioman/gunner, an aviation ordnanceman, and an aviation mechanic.

In its theoretical role of scout plane, the pilot would fly out of sight of the ship searching for enemy shipping. As a spotting plane for shore bombardment, it would circle between the ship and the beach, relay information about the target, and assist in directing the ship’s fire. The plane could also carry depth charges and bombs to be used against enemy submarines, but this was considered a secondary role. Because it lacked tracking gear, the plane could only be used against submarines if its crew spotted a periscope or a Japanese submarine running on the surface. The plane could also be used for mail runs when the ship had been at sea for extended periods of time, and on at least one occasion aboard the Stevens it was used for towing target sleeves for gunnery practice.

Commissioning the New Destroyers

The Hutchins, Pringle, and Stanly were all commissioned in 1942, and the Stevens and Halford in 1943. The Pringle was the first of the destroyers to actually have the catapult and related equipment aboard, and in January 1943 it became the first destroyer to launch an airplane from its own deck. However, during the recovery process a design flaw was found in the hoisting equipment and the ship was unable to recover the airplane as planned. The catapult, hoist, and related equipment were removed shortly thereafter. The equipment was also removed from the Stanly about the same time.

The Stevens and the Halford were launched after the catapult equipment had been removed from the other three ships. Fitted with a redesigned hoist, the Stevens was commissioned on February 1, 1943; the Halford was commissioned on April 10, 1943. Of the six ships originally selected for the modification, only these two ships went into combat with planes aboard.

48 Launches and Recoveries

At 8:30 am on Tuesday, April 6, 1943, at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, Rear Admiral Morton Deyo, Commander of Destroyers, Atlantic Fleet, came aboard the Stevens to watch the first launching of its Kingfisher. Shortly after 9 am, Lieutenant H.W. Smith, the pilot, climbed into the cockpit and fired the engine. He brought the engine to full throttle, set the trim on the plane so that it would fly even if he were to black out from the force exerted on him by the launch, and signaled to Leroy Fadem, the torpedo/catapult officer, that he was ready. Ensign Fadem gave the order to fire the catapult, and at 9:14 the plane roared down its length and into the air. The plane was back aboard by 11:25, making Stevens the first destroyer to successfully launch and recover an airplane, thereby carving a niche for itself in U.S. Navy history. The crew would eventually conduct a total of 48 successful launches and recoveries. While the hoist performed without a problem, a recommendation was made that additional bracing be added to strengthen it, which was done upon the Stevens’ return to the states.

Following shakedown cruises in the Atlantic, where she steamed from Guantanamo Bay to Portland, Maine, the Stevens passed through the Panama Canal on July 26, 1943, on the way to Pearl Harbor. There she met up with the Halford, which had departed from San Diego on July 5 and arrived in Pearl Harbor five days later. In the early stages of their tours the two ships operated with each other as they tested the feasibility of carrying the scout planes on smaller vessels. Both ships participated in the Marcus Island raid on August 31, 1943, and returned to Pearl Harbor on September 7. During the return from Marcus Island, both destroyers launched and recovered their aircraft. Both conducted patrol duty near Hawaii until they temporarily parted company, with the Stevens participating in the Tarawa attack on November 19, 1943, and the Halford in the Wake Island attack on October 6, 1943. That same day the Stevens began its return voyage to Mare Island, California, near San Francisco, to have its forward 20mm guns replaced with Bofors 40mm guns.The Halford followed shortly thereafter. Following reconfiguration of the standard Fletcher design, both left Mare Island on December 6, 1943, and arrived in Pearl Harbor on December 10.

Troubles With the Sea Plane

Living with the seaplane was not easy, and the sailors aboard the Stevens did not like having it aboard. Although the plane itself was more than capable of doing its job when in the air, its presence aboard the Stevens created a number of problems for the ship and its crew. The installation of the catapult and subsequent removal of the guns that would normally have been there caused a significant loss in firepower vital to the ship’s defense. The presence of the plane also made the destroyer appear to be a light cruiser and cultivated the fear among the Stevens crew that the ship might be mistaken for one and consequently draw additional enemy fire or air attack. Finally, the huge fuel tank presented a potential catastrophe should it be hit by enemy fire. These thoughts may also have crossed the minds of Navy brass, for following the Tarawa attack the Stevens remained in the vicinity of Pearl Harbor conducting antisubmarine warfare exercises until its departure for Mare Island to be refitted. Immediately following the Wake Island raid, the Halford was also ordered to Mare Island.

Repairing the airplane when the ship was at sea was also a problem. Replacement parts stored aboard ship were not always sufficient to make repairs to the plane, necessitating a return to port and reducing the amount of time actually spent at sea. The alternative was for the plane to be inoperable for a period of time. A related problem, albeit minor, was of special concern to the aircrews. They were paid a premium for logging a specified number of hours in the air. If they did not fly, they did not get paid the premium. Naturally, the air crews wanted to log as many hours as possible.

Difficult Recoveries

Perhaps the biggest problem created by the plane, however, was recovering it while at sea. The placement of the catapult and airplane amidships, rather than at the stern as on most cruisers and battleships, created a number of problems. In heavy seas, the destroyers would roll, and if the plane was suspended from the hoist, it would alternately bang into the side of the ship when it rolled to starboard or crash into the ocean on the port roll, damaging both the plane and the ship. This was less of a problem on cruisers and battleships because the larger ships tended to be more stable and the scout plane was launched and recovered from the stern of the ship. The destroyers did not have the luxury of the extra room; the stern was reserved for depth charges and smoke screen generators.

Standard recovery procedures for shipboard planes included a turn by the ship, thus smoothing the water behind the ship and creating a place for the plane to land. Battleships and cruisers had no problem creating this “slick.” The two destroyers, because they were much smaller, were not always successful in this endeavor, especially in heavy seas.

Finally, while the plane would land behind the ship it had to taxi to the side of the moving destroyer and onto a rope “sled” to be hoisted aboard. Because the ship was normally moving faster than the plane could taxi, the ship itself would have to slow down considerably, coming to a virtual standstill.

A barely moving American warship at sea made an excellent target for Japanese submarines. While neither ship was actually attacked while recovering the plane, the sailors aboard the two ships nonetheless were relieved when the plane was back aboard and the ship was underway once more.

A Disastrous Demonstration

First Lieutenant Stan Lappen, damage control officer of the Stevens, recounted an incident that occurred during the recovery of the airplane. “We were returning from a raid on Tarawa Island when the Task Force Commander [Rear Admiral Charles Pownall] wanted to see how the plane operated off a destroyer. We launched the plane, and it made a few runs around the Task Force before coming in. The sea was choppy and the plane was having trouble making much headway on the water after it had landed, and we couldn’t make much of a slick to smooth the water for it. We had to slow down to almost a stop so the plane could catch up to us.

“We finally got the winch cable attached to the plane, but we were moving so slowly that we were rolling heavily from side to side. Since we had to pick the plane up off the port quarter, the roll was a problem. It was necessary to get the plane up rather quickly once it was hooked onto the cable. Just as we got the plane out of the water, the power temporarily failed on the crane, leaving the plane dangling on the end of the cable. As we rolled to port the plane hit the water, and as we rolled to starboard it swung into the ship. The pilot, my roommate [Lieutenant (j.g.) Hal Smith], jumped from the plane and caught the life rail. We grabbed him and pulled him on board. His radioman-mechanic jumped or fell into the water and had to be picked up by the motor whaleboat. The plane hit the side of the ship a few times, demolishing its wing. It looked AWFUL!”

Electrician’s Mate 1/C William Wickham recalled that the pilot had extricated himself from the plane and had managed to get out onto the wing, where he made a perfectly timed leap toward the destroyer as it began another roll and just before the airplane smashed into the ship again. Smith, the pilot, was grabbed by a “big, brawny machinist’s mate who just happened to be standing there watching the operation” and pulled aboard. According to Wickham, cheers erupted from the onlookers. Wickham also recalled that the radio operator who had taken the unexpected dip into the Pacific had several comments that he shared with the crew, mostly about the intelligence of the their ancestors.

Launching the Kingfisher

Launching the plane could be equally difficult. Lappen also provided this interesting insight into the launching process, as well as to what the crew of the airplane was thinking during the launch. “When I first went on board the Stevens, the pilot was my roommate. During the night he would have nightmares, yelling, “Now! Now!” I asked him about this, and he explained. Since the catapult was about amidships, it had to be swung out at a right angle to the ship’s progress for the launch. This meant that the ship’s headway did not provide any headwind for the plane as it traveled down the catapult. The OS2U needed 90 knots to become airborne. The short catapult plus no headwind meant that it would just barely make the 90 knots at the end of its catapult run. With the catapult out at right angles to the ship’s heading, the roll of the ship would be increased and could be used to help the plane’s launch. However, the catapult charge had to be fired when the catapult was at its lowest point, so that the roll toward the opposite side would raise the catapult end, flipping the plane into the air as it left the catapult. The pilot’s nightmare was that the torpedo officer might not fire the catapult charge at the right time and the plane would arrive at the catapult end on the down roll, driving the plane directly into the drink.”

The Stevens made many successful launches, never sending the plane into a 90-knot dive into the ocean, but it was always a harrowing experience for the pilot and radio man, as well as the Stevens crew.

Ending the Experiment

Life with the seaplane was not easy, even when it was not being launched or recovered. Seaman 2/C William E. Wenger was aboard the Stevens from its commissioning in Charleston until just before it returned to Mare Island. He was transferred to another ship at Pearl Harbor. He recalled this incident aboard the Stevens. “We went on a shakedown cruise to Cuba and the surrounding waters. Of course, there were German subs in the area, so the plane was always swung out on the catapult during morning and evening General Quarters. One day we were shooting at towed targets from land-based planes for antiaircraft practice as well as for making adjustments on the firing arcs of our shipboard 20mm and 40mm guns. The guns were fitted with ‘stops’ to prevent them from rotating and firing past a certain point. However, during one practice session, the stops failed on one of the 20mm and the gunners shot the tail off the OS2U. I never saw two guys abandon an aircraft so quickly! The skipper and the gunnery officer were ticked off, and we wound up with a bunch of junk on our catapult.” The damaged airplane was replaced upon the ship’s return to the United States.

In July 1943, just prior to the Stevens’ departure for the Pacific Theater, Rear Admiral G.J. Rowcliff came aboard. Admiral Rowcliff conducted interviews with the ship’s officers and came to the same conclusion that everyone aboard the Stevens already had: an airplane aboard a destroyer was not a practical idea. In a letter to the general board, he wrote, “This installation would be of extremely limited usefulness on account of the difficulties of stowage, handling, service, launching, and recovery. It would appear that the use would be limited to messenger or quick reconnaissance work of a special nature under favorable conditions of use, operating by stealth or without much opposition.” Nonetheless, the Stevens steamed for the Pacific still carrying her albatross.

While the Stevens was performing its duties in the Pacific, the conversation regarding the catapult and the airplane continued back in the States. The Bureau of Ships (BuShips) requested that the Norfolk Navy Yard submit plans and a cost analysis for widening Stevens’ deck around the catapult. The plans were submitted on September 8. Convinced of the uselessness of the catapult-equipped destroyer, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, had seen enough. On October 13, he requested authorization from BuShips to have the equipment removed from the Stevens and the Halford, and Admiral King, who had opposed the idea from its inception, concurred. On October 15, 1943, the order was issued directing the removal of the equipment from the two ships. The Stevens was already at Mare Island for installation of the 40mm guns when the order was issued. After conversion to conventional Fletchers, the two departed Mare Island for the Pacific in December.

From Kingfishers to Helicopters

The Stevens’ experiment with the seaplane lasted slightly more than a year, but it certainly provided memorable experiences for the crew. During the time the plane was on the Stevens, the ship participated in two engagements with the Japanese, the raid on Marcus Island on August 31, 1943, and the attack on Tarawa on November 19, 1943. During both actions, the Stevens was part of a carrier group that provided the air cover for the task group, and its Kingfisher was never used for antisubmarine warfare or fire direction. It was used occasionally in its role as a scout plane, but it never spotted any Japanese shipping or encountered any Japanese airplanes.

In retrospect, the idea of mounting an airplane aboard a destroyer may have seemed like a good idea in 1940, when there were fewer ships with the capacity to launch aircraft. However, with the massive buildup of the American fleet by 1943, the destroyer-mounted observation plane was an idea whose time had passed. Due to their greater size, the newer battleships and cruisers could more easily handle the problems associated with the airplane. It should be noted, however, that aviation did eventually return to the decks of destroyers, when the Navy began equipping a much later generation with helicopters.

The Stevens and its sister ships were ahead of their time, but they proved that aircraft could successfully operate from smaller naval vessels.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments