By John Niesel

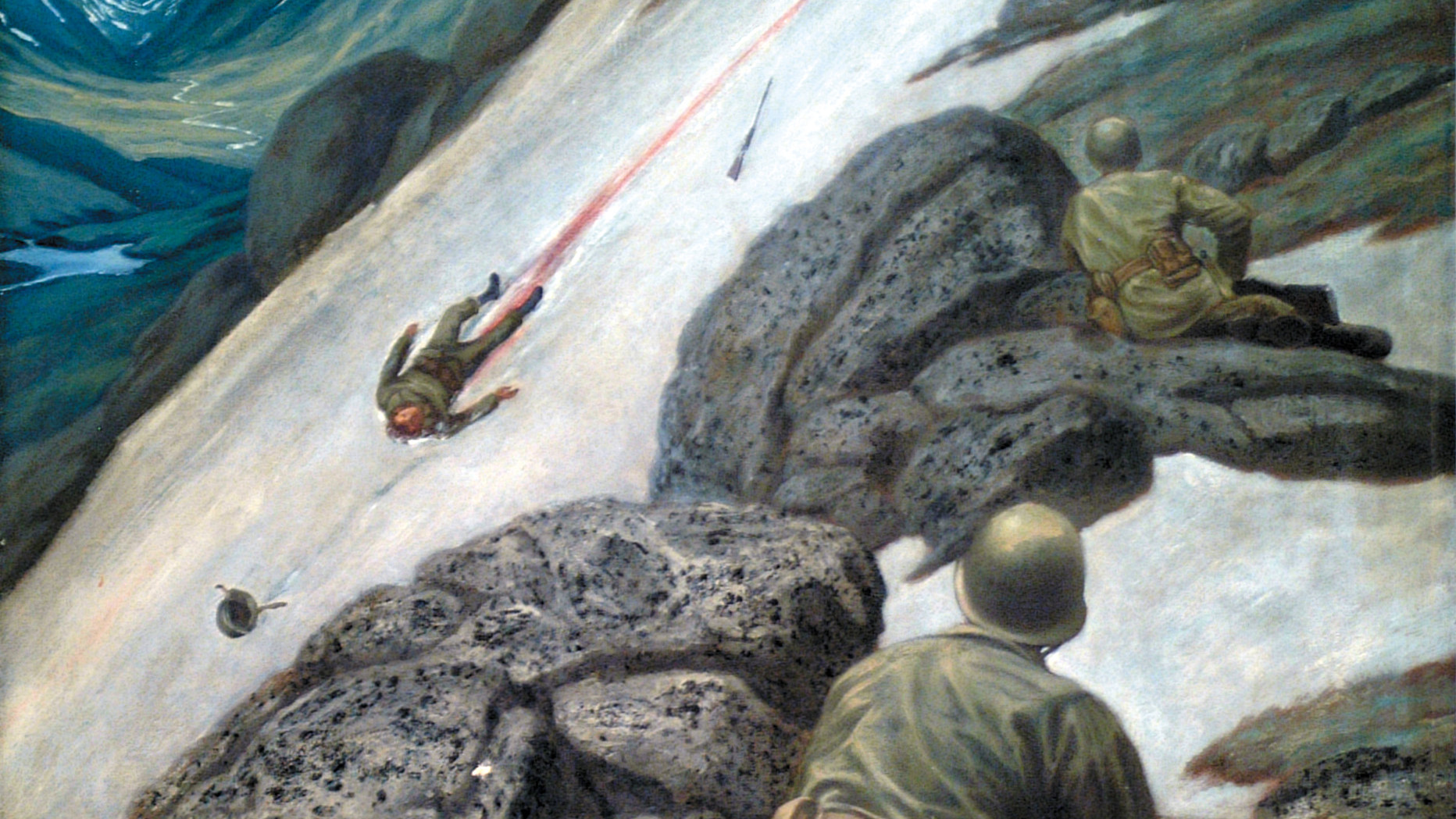

Early in 1945, in the Northern Appenine mountains of Italy, T/5 Harvey, a radioman with the 10th Mountain Division, is carrying his WW2 radio backpack, the ever-handy SCR-300, into combat for the first time. His company is part of an advance by the 10th, the only U.S. Army division that has extensively trained for mountain warfare. The 10th’s objective is to push the Germans off of the mountainous high ground that they have held for many months despite repeated, persistent attempts by the Americans and British to take the heights. But the mountain troopers of the 10th are up to the task.

Harvey is moving slowly forward with his company commander, monitoring the airwaves for any incoming transmissions. He and his fellow GIs are at the point of the attack in their sector, and soon they run into the German main line of resistance. Heavy firing breaks out directly in front of the Americans, and Harvey hits the deck along with the other mountain troopers. “I could hear the bullets whizzing over my back and smacking in the dirt around me,” he recalls.

So Harvey keeps his head down and radios in a contact report. His company quickly gets organized and starts bringing steady return fire to bear in the direction of the German positions. After a short while the enemy fire subsides, and the troopers continue their advance. But soon German rifle fire forces Harvey to hit the ground again—with 35 pounds of radio strapped to his back. He transmits another contact report while, and once more, the enemy bullets buzz close overhead and hit the earth around him.

This same scenario repeats itself many times over the next few days, and Harvey keeps hitting the dirt, the SCR-300 pounding his back, bullets still flying close over his head and smacking into the ground around him—while the radio’s antenna is wagging back and forth.

“After a week of this,” he relates with a wry smile, “I suddenly realized that whenever we came under heavy fire and hit the ground, most of the other guys around me weren’t taking any direct fire at all while I had bullets flying all around me. Then it hit me—it was the radio’s antenna that was attracting the German rifle fire! To maintain good reception I had to keep the antenna vertical, which was easy to do as it had a flexible mount. Whenever I was lying prone on the ground, I would swing the antenna vertical. So there I am, my face in the dirt, and there’s that antenna poking up, dancing around, and drawing all kinds of attention to me. After the firing stopped, I turned to the captain and told him that I didn’t want to carry the radio anymore—I was tired of getting shot at!”

Designing the WW2 Radio Backpack that Became the “Walkie Talkie”

On the World War II battlefield, there were few options for sending messages. One was to send a messenger or runner—who risked getting killed, wounded, lost, or captured. Another was the field telephone. But it was dependent on wire, which, when strung along bushes and trees, or, more likely, just laid on the ground, was easily damaged by boots, tires, tank treads, and exploding munitions. GIs of the U.S. Army Signal Corps and the U.S. Marine Corps devoted a lot of time to locating and repairing line breaks. All the while, messages weren’t getting through unless sent by runner, jeep, etc.

Effective though it was, the field telephone just wasn’t portable enough to move out with the troops at a moment’s notice. However, as is often the case in peace and war, technology came to the rescue with an innovative, game-changing invention: wireless—better known as a radio.

The vacuum tube made radio possible. These cyndrilical-shaped, glass-enclosed electronic devices were the precursor to the modern transistor. With a design that was refined throughout the early 20th century, vacuum tubes became increasingly smaller and more robust. By 1940 they were dependable, of compact design (about the size of a small pill bottle), and could be made rugged enough to withstand shock, vibration, heat, cold, and wet. With these attributes in mind, the U.S. Army Signal Corps embarked upon a design program to develop a “Walkie-Talkie”—a portable AM frequency radio that could be carried on a soldier’s back.

Prior attempts at designing a portable radio were made in the late 1930s and early 1940s, with some success achieved with the SCR (Signal Corps Radio) 194 and 195 backpack radios, but they were cumbersome and heavy, and had tuning and reliability issues. Another radio that made it to operational status was the SCR-511, issued to the troops in 1942. The 511, with its long, staff-like antenna that was bisected by the coffee can-size transceiver, was given the nickname “Pogo Stick.” Designed for cavalry use, it was outmoded by the time of America’s entry into World War II, but saw service nonetheless.

Galvin Manufacturing Corporation’s FM Radio

In 1940, Galvin Manufacturing Corporation—maker of Motorola products—had developed the “Handie-Talkie” SCR-536 handheld two-way AM radio that would see extensive use in the upcoming war. But with an effective range of only a quarter of a mile, the SCR-536 was not powerful enough for communications between advancing troops and company/battalion headquarters situated farther back from the front line. Nor was it manually tunable to other frequencies or “channels,” thereby limiting its usefulness. A new radio was needed, one that could reliably operate over a longer range, but still be portable enough to not be overly burdensome to the soldier carrying it.

As previously mentioned, the initial Signal Corps design parameters were for a radio that would operate on the AM (Amplitude Modulation) band. However, one of Galvin’s engineers, Daniel Noble, was sold on the advantages of FM (Frequency Modulation) design for clear, interference-free radio communication. He met with representatives from the Signal Corps and convinced them of the superiority of FM technology for their new radio.

Noble’s confidence in the viability of the concept and in Galvin’s ability to produce such a radio carried the day. Although various sources give differing dates for when these initial design discussions transpired, in 1942 the Signal Corps issued to Galvin Manufacturing a contract for the development of a portable transmitter-receiver utilizing the FM band. It was a high-priority project, and Galvin began design work without delay.

The SCR-300

Daniel Noble was tasked with assembling the project team. Joining him were Marion Bond, Henryk Magnuski, Lloyd Morris, and Bill Vogel. The Signal Corps stipulated that the radio, designated SCR-300, was to be powered by batteries, and, weighing no more than 35 pounds, be portable enough to be carried on a soldier’s back. The transmitter and receiver would utilize the FM band of 40.0 to 48.0 megacycles, divided into 200 MHz segments in order to yield a total of 41 channels. An operational distance of three miles was specified, with the appropriate noise-cancelling circuits to facilitate clear reception.

Finally, as the unit was intended for extended use outdoors in all types of weather conditions, the radio set had to be resistant to water entry. Noble informed the men that the Signal Corps “placed a life-and-death priority on this program for the infantry.”

The SCR-300 team took their responsibility to heart, and by spring 1942 they had two prototypes ready for review. After successfully testing the radios eight miles apart (more than twice the distance called for in the initial specifications), the units were demonstrated for representatives from the Signal Corps. So impressed were they that the go-ahead was given to proceed with the program. Further development and testing led to the production radio, the BC-1000. This unit, when combined with all of the required accessories, comprised the SCR-300 “Walkie-Talkie” radio.

For the Army’s final acceptance tests, Galvin’s production version of the SCR-300 traveled to the home of the U.S. Army’s Armored Force School at Fort Knox, Kentucky. There in the woods and fields the unit was put through its paces, with trials and tests designed to verify the performance characteristics, ruggedness, and overall quality and usability of the radio. As the results demonstrated at day’s end, Daniel Noble’s project team had designed a winner that met or exceeded the specifications laid out in the initial Signal Corps parameters.

Full-scale production ramped up following the conclusion of the acceptance tests, with ensuing delivery of operational units to the Army for the purpose of writing the requisite technical manual that would accompany every SCR-300 issued to a radioman. This manual, which was titled “TM 11-242 RADIO SET SCR-300-A,” detailed the correct set-up, operation and troubleshooting of the BC-1000 radio and accessories.

An Easy to Use System

Initially assigned to GIs who had completed the required courses on radio communication, the SCR-300 was nonetheless fairly easy and straightforward to use. As such, the unit could be operated by just about anyone after a brief introduction regarding tuning, transmitting, and receiving. Once powered on, the vacuum tubes required a 10-minute warm-up period, then the unit was ready to operate. Select a channel with the tuning dial, adjust the squelch knob (to reduce background noise or “roar” that occurs when the radio isn’t transmitting or receiving), and simply push the butterfly switch on the telephone-like handset to transmit, release the switch to receive (as the SCR-300 was a radio, it could not transmit and receive simultaneously), and that was all that was required for basic operation.

One major reason for the SCR-300’s ease of use is that Noble’s team designed the BC-1000 radio unit with an electronic circuit, called Automatic Frequency Control, that would automatically fine-tune the radio to match the frequency of an incoming signal. This circuit allowed outgoing transmissions from the BC-1000 to be sent out on the exact same frequency, negating the need for a separate tuning control for transmitting. This was a simple concept, perhaps, but an important feature that made the radio easy to use by those who may have to operate the unit if the radioman was wounded or killed. One hallmark of a successful design is simplicity of use, and as Galvin would end up producing nearly 50,000 SCR-300s—many of which remained in use well into the 1950s—the success of the radio’s design was clearly proven.

Combat Debut in Italy

As the Allies were concluding the campaign in Sicily in August 1943, operational planning for the upcoming invasion of Italy was in its final stages. Communication SNAFUs throughout the North African and Sicilian campaigns served to reinforce the immediate need for more effective means of portable communication.

Because of this need, and since there were now enough units available for deployment, Galvin’s SCR-300 would be slated to make its combat debut during the invasion of southern Italy. In fact, such importance was placed on including the new radios in the operation that they were transported by air to the invasion staging areas. Alternate shipment by cargo ship was considered too slow, and many times urgently needed items had been “lost” in the vast cargo holds of the hundreds of Allied ships plying the Atlantic. Consequently, assigning precious air transport space to the delivery of the radios ensured they would be in the hands of those who would desperately need them once the bullets started to fly.

Deployed primarily to facilitate timely communications between infantry companies and battalion HQ, the SCR-300s were also frequently used by forward observers who would spot the fall of artillery rounds, then, if needed, quickly radio back aiming corrections. The practical usefulness of the units, and the dependability of the radio’s rugged design, quickly became apparent once the GIs waded ashore in Italy. The U.S. Army was still experiencing many teething troubles in 1943 when fighting the Axis, and the instant communication afforded by the new radios was a godsend to the frontline soldiers and commanders. When there was an immediate need for reserve troops or a concentrated artillery barrage, the SCR-300 was worth its weight in gold.

The SCR-300 in the European and Pacific Theaters

As production of the SCR-300 continued, the radios were issued to other units and branches of the U.S. military besides the infantry. The Army Airborne, the Marines, and the U.S. Navy all received radios for their own use. By the time of the invasions of northern and southern France in June and August of 1944, Galvin’s “Walkie-Talkie” was playing a prominent role in communications in the European Theater of Operations, as it also was with Marine and Army units that were carrying out the island-hopping campaign against the forces of Imperial Japan in the South Pacific.

Use of the SCR-300—and any other electronic device for that matter—in the extreme heat and humidity that was encountered in the Pacific Theater required a fungicide treatment if the equipment was expected to function reliably. Galvin employed a fungus-prevention process that applied a protective coat of varnish over the entire assembled circuit board. This coating, along with the rubber grommets that sealed the case sections, were effective at preventing moisture-induced damage to the radio’s electronic components.

The Problematic SCR-300 Battery

As indispensable as the SCR-300 proved itself to be in the field, one inherent characteristic of a portable radio could render the unit useless: battery life, or, more specifically, inavailability of replacement batteries. This could turn the radio into nothing more than 35 pounds of dead weight on an infantryman’s back. To minimize the possibility of such scenarios, the Army and Marines made replacement batteries a high-priority supply item, similar in importance to ammunition and rations.

One radioman who was interviewed for this article went ashore in southern France with the 103rd Division in fall 1944. He recalls few problems with obtaining replacement batteries throughout his seven months in combat. From the port of Marseilles to Brenner Pass in southern Austria, he doesn’t recall having to go any extended amount of time with a dead battery.

The multi-voltage SCR-300 batteries—available in two sizes—were more complicated than a single-voltage jeep or truck battery. The 15-pound BA-70, with an operational life of 20 to 25 hours, was the first SCR-300 battery produced. It was later followed by the lighter-weight (9 pounds) BA-80, which had an operational life of 12 to 15 hours. Inside of both battery assemblies were three groups of power cells, with each group supplying a different voltage. A 4½-volt group powered the filaments of the 18 vacuum tubes, while a 90-volt group powered the receiver plate. Power from the third group of 60 volts was combined with the receiver’s 90-volt cells to provide the 150 volts required by the transmitter plate.

With the existing battery technology of the day, such a diverse power supply required a large physical package. As a result, the lower two-thirds of the SCR-300 unit was occupied by the battery, which connected to the BC-1000 receiver/transmitter via a thick seven-prong cable. The inclusion of such heavy-duty components as the cable; the rubber grommets between case sections; hinged seal covers over the headset, handset, and relay jacks; strong steel outer case; and the compact but sturdy circuit board construction played a big role in the radio’s ruggedness, the benefits of which were experienced firsthand by frontline troops.

WWII’s Invaluable “Walkie-Talkie”

Throughout World War II, the SCR-300 radios distinguished themselves under combat conditions in hot weather and cold, wet and dry. Battalion and company commanders finally had a dependable radio that was truly portable, allowing instantaneous communications regarding immediate tactical needs and actions. Forward observers were able to quickly call in the U.S. Army’s substantial artillery assets, making corrections rapidly and often with devastating effects on enemy infantry and armor.

Marines fighting int the jungles and on the islands of the Pacific could coordinate with Marine armor via the “Walkie-Talkie,” bringing much-needed heavy, close-in firepower to bear on Japanese pillboxes, caves, and strongpoints.

And, of course, untold numbers of American and Allied lives were saved by the timely and accurate communication allowed for by Galvin Manufacturing Corporation’s SCR-300 Radio Set. The U.S. Army placed such importance on the development of the radio that they awarded Daniel Noble the Certificate of Merit for his role in the design and production of the “Walkie-Talkie.”

By the end of the war, Daniel Noble’s design for a dependable, rugged, easy-to-use WW2 radio backpack saw extensive use in combat with the Marines, Army Infantry and Airborne, Army Air Force, and Navy.

Portable in theory, and portable when put into use, Galvin Manufacturing Corporation’s “Walkie-Talkie” was arguably one of the most useful items provided to U.S. servicemen during World War II—even though that “dancing” antenna may have brought a few more enemy bullets zipping over the radioman’s head!

Very interesting as the importance of prompt tactical info communication between support units and other troops in the area is often overlooked in battle success. I’m sure that accuracy & effect of artillery & air support were greatly enhanced in the GI’s favor.

What year was this article published?

The URL (web link) shows this article was published on 2019/01/26

To clarify, nearly all the stories on our website were first published in our print magazines. So the date in the URL does not actually reflect the original print publication date.

Thanks Carl.

I stand corrected.

Could this radio communicate with USAAF planes flying overhead? Could frontline, forward ground troops call in airstrikes with the SCR-300?

The short answer: No. During WWII, The air force did not have FM modulated radios in the 40-48 MHz band in which the SCR300 operates. Only in the Fifties did air force radios become available for that, they were called “liaison radios”. A good example is the AN/ARC-44 which allowed pilots to communicate directly with army troops on the ground, using FM radios. The AN/ARC-44 was capable of communicating directly with the SCR300 radio, although the latter was already being replaced with the smaller PRC-10 manpack radio at the end of the Fifties.

For the AN/ARC-44 see here: http://www.vintageavionics.nl/index_bestanden/ARC44_FM.htm

For the PRC-10 man-pack radio see here: http://www.vietnamgear.com/kit.aspx?kit=517

As an ex SGT of RAAF involved in repair of aircraft communications and teaching electronic theory to trainees. I would like to know more about the logistics of keeping the field radios repaired in the European theatre. Also for that matter how they were kept serviceable in any theatre they were used. There must have been a repair centre well behind the front lines one would assume. I have read the service manual for the SCR-300 and it is intended for well trained and experienced personnel to carry out repairs and adjustments. Also at a transmitting frequency of 40 to 48 Mhz the range would basically have been line of sight only, being as it was the lower end of the VHF band. Also interesting to note miniature 7 pin (B7G socket) battery electron vacuum tubes were used that were not that particularly rugged and would have been subjected to relatively hard knocks in the field.

Regards Robert Scott