By Michael E. Haskew

As the 450 ships of the Operation Avalanche invasion force approached Salerno on the evening of September 8, 1943, the Allied troops, packed tightly aboard transport vessels, broke into wild celebration. Italy had surrendered, and many of the invaders in the ships thought German opposition on the beachhead might be light or nonexistent.

“I never again expect to witness such scenes of sheer joy,” wrote Major Warren A. Thrasher, Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s aide-de-camp. “Speculation was rampant and it was all good…. We would dock in Naples harbor unopposed, with an olive branch in one hand and an opera ticket in the other.”

Senior commanders knew, though, that the Germans intended to fight regardless. Actually, in addition to extensive military preparation, the days leading up to the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland had been filled with intrigue and political maneuvering. In the higher echelons of the Allied command there were few delusions of an easy march through Italy. Their troops had already fought a bloody campaign in North Africa and were only halfway across Sicily. Now, invading Italy and pushing the Germans up the mountainous Italian “boot” while persuading the Italians themselves to offer no resistance amounted a jumble of potential scenarios.

“Italy is in Pieces”

Six weeks earlier, late on the afternoon of Sunday, July 25, 1943, as the Allies were still battling across Sicily, more than 20 years of Fascist rule in Italy had come to an abrupt and unceremonious end. A car carrying Benito Mussolini, Il Duce, arrived at the Villa Savoia on the Via Salaria in Rome. King Victor Emmanuel III was waiting.

The downfall of Mussolini’s government had inevitably arrived because of the Allied advance in Sicily and the growing weariness for war among the Italian people. Rationing had become extreme, with the daily allotment of calories down to less than 1,000 per person. Air raids were taking lives and devastating cities, diminishing the resolve of the common folk to follow a fading dream of empire.

“My dear Duce,” the 74-year-old monarch said to Mussolini following a 19-to-7 vote by the Grand Council to remove the Fascist leader from office, “it cannot go on any longer. Italy is in pieces. Army morale has reached the bottom and the soldiers do not want to fight any longer. The Alpine regiments have a song saying that they are through fighting Mussolini’s war. The result of the votes cast by the Grand Council is devastating…. Surely, you have no illusions as to how Italians feel about you at this moment. You are the most hated man in Italy; you have not a single friend left, except for me. You need not worry about your personal security. I shall see to that. I have decided that the man of the hour is Marshal [Pietro] Badoglio.”

The stunned Mussolini was driven from the meeting in an ambulance and placed under guard in a military barracks. For a while, he entertained the notion that the confinement was for his protection, but slowly he realized that he had been placed under arrest. An enraged Hitler vowed to retaliate by arresting the members of the new Italian government, the royal family, and even the Pope. While he was dissuaded from this course of action, he nevertheless intended to rescue Mussolini.

Eventually, Il Duce, still under arrest, was located in the Campo Imperatore Hotel, a ski lodge high atop the Gran Sasso in the Abruzzi Mountains. Hitler authorized a daring, glider-borne rescue attempt, and SS commandos under Captain Otto Skorzeny plucked the deposed leader from his captors and took him to northern Italy.

“Badoglio Admits He is Going to Double-Cross Someone”

Marshal Badoglio, who had previously served as the chief of the armed forces general staff in the Fascist government, formed a new government and made overtures of peace to the Allies. In early August 1943, Italian diplomats had secretly met with two high-ranking staff officers of the supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. His chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, and his intelligence officer, British Brigadier Kenneth W.D. Strong, had met the Italians in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon.

Badoglio’s envoys stated that the desire of their new government was to not only surrender but also to change sides and fight the Germans. In exchange, Badoglio wanted assurance from the Allies that they would land in force on the mainland and execute an airborne operation to liberate Rome before the Germans could occupy the Eternal City.

The Italian nation was caught between the proverbial devil and the deep blue sea. To some, it was virtually impossible to distinguish which was the greater threat. The Allies were bombing Italy’s cities with impunity and they were unlikely to be in a conciliatory frame of mind, particularly when it came to the prospect of fighting alongside such a recent enemy.

In fact, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stated bluntly, “Badoglio admits he is going to double-cross someone.”

Unconditional Surrender

Eisenhower’s representatives had gone to Lisbon to arrange terms for the unconditional surrender of Italy. Undoubtedly surprised by the overture of military cooperation, they relayed the proposal to Eisenhower. While he was interested in working with the Italians if it meant less resistance, the supreme commander’s assessment of the situation was also practical.

“Then began a series of negotiations, secret communications, clandestine journeys by secret agents, and frequent meetings in hidden places that, if encountered in the fictional world, would have been scorned as incredible melodrama,” Eisenhower wrote later. “Plots of various kinds were hatched only to be abandoned because of changing circumstances…. The Italians wanted frantically to surrender. However, they wanted to do so only with the assurance that such a powerful force would land on the mainland simultaneously with their surrender that the government itself and their cities would enjoy complete protection from the German forces.

“Consequently they tried to obtain every detail of our plans. These we would not reveal because the possibility of treachery could never be excluded. Moreover, to invade Italy with the strength that the Italians themselves believed necessary was a complete impossibility for the very simple reason that we did not have the troops in the area nor the ships to transport them had they been there….”

After several weeks of political wrangling, the Italians, on September 3, were obliged to accept unconditional surrender terms. The surrender, however, was not to be announced to the world until September 8, the eve of the landings by Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army on the beaches at Salerno, south of Naples.

“Situation Innocuous”

Brigadier General Maxwell D. Taylor, the artillery commander of the 82nd Airborne Division, and Colonel William T. Gardiner, an officer of the U.S. Army Troop Carrier Command, were dispatched on a dangerous mission to Rome on September 7 to evaluate the risk associated with a planned airborne drop on the city. Taylor was instructed to send the single word “innocuous” if, in his judgment, Giant Two, the proposed airborne operation, should be scrapped and the Italians were either unable or unwilling to send their own cancellation message.

A British motor torpedo boat transferred the American officers to an Italian Navy corvette, and the emissaries reached the shore near Gaeta. Their uniforms were splashed with water and mud to give them the appearance of airmen who had been shot down and rescued. Following a ride in a car and an ambulance, they reached Rome, safely skirting several German patrols. The Americans were offered a fine dinner but became irritated when no Italian official of consequence appeared to discuss the situation. Eventually, they were brought to Badoglio, who reiterated his pro-Allied stance and his concern that German forces would occupy Rome.

Given the circumstances, Badoglio decided to send a message to Eisenhower, effectively canceling his earlier commitment for an immediate armistice. Taylor sent a message of his own. Both urged that Giant Two be canceled. Taylor sent a third message late on the morning of September 8: “Situation innocuous.” It was received hours before the transport aircraft had been scheduled to take off.

The purpose of the announcement of Italy’s surrender being delayed until the 8th was to confuse the Germans, so Badoglio’s message was ignored by Eisenhower. Ike announced the surrender as planned while the invasion force off the Italian coast at Salerno was preparing to land. Badoglio had no choice but to go along with the announcement.

The German Occupation of Italy

Hitler was not surprised or confused in the least by the surrender announcement, for he fully expected the Italians to turn tail once their mainland was threatened. In anticipation of the event, he had ordered a concentration of more than 12,000 airborne troops with supporting artillery to move to the vicinity of Rome, along with the 24,000 men and 150 tanks of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division.

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, a former Luftwaffe officer who would perform brilliantly during the arduous campaign to come, maintained overall command in Italy south of a line running from Pisa to Rimini, and he was ably supported by Col. Gen. Heinrich von Vietinghoff gennant Scheel. In northern Italy, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was in command of eight divisions. Depending on the location of an Allied invasion, each could be mutually supportive of the other.

The Germans also cut fuel and ammunition deliveries to Italian Army units, and wherever German forces were deployed near Italian coastal defenses, they were instructed to be ready to assume those defenses and disarm the Italians. The German military was in position to take control of Italy by force if necessary.

When the Germans moved to occupy Rome, which was to endure eight months of oppressive Nazi occupation, King Victor Emmanuel III, Marshal Badoglio, and members of the new government escaped to the south aboard a British warship.

Three Avenues of Attack Against the Italian Mainland

The success of Operation Husky in Sicily and the ouster of Mussolini caused the Allied war planners to rethink their strategy. Instead of moving against the islands of Sardinia or Corsica, whose strategic value was limited, it became reasonable to consider the advantages of an assault on the Italian mainland.

The political situation in Italy had a direct impact on the military situation. Initially, Allied planners had been conservative in directing the course of the war after the campaign in Sicily. In the spring of 1943, their considerations were limited to occupying as much of the German armed forces as possible to relieve the pressure on the Soviet Red Army in the east and potentially compel Italy to surrender.

A landing on the coast near Rome was ruled out because it was beyond the range of supporting aircraft, which would be flying from bases in Sicily. Naples, too, was eliminated because its built-up harbor and congested urban core would too quickly lead to tough street fighting. Although farther south, Salerno, with its broad, sandy beaches and plenty of maneuver room, offered the greatest chance of initial success.

Although the Germans were bound to contest such a landing fiercely, it was determined that planning for an invasion should go forward. A number of deception plans were implemented to keep the Germans guessing as to where the invasion of Italy—if it came at all—would take place.

Three avenues of approach were authorized. First, General Sir Bernard Law Montgomery, hero of the North Africa campaign, was to command the British Eighth Army’s XIII Corps—which consisted of the 1st Canadian and Fifth British Infantry Divisions, attached armored and infantry brigades, and several Commando units—during the short amphibious run across the Strait of Messina to Reggio Calabria, on the toe of the Italian “boot.” The main effort, a landing by Clark’s Fifth Army at Salerno, would then take place. Montgomery’s command was to then advance northward 200 miles to link up with the Fifth Army lodgment and join in a combined movement northward to Naples and beyond.

In addition, on September 9, the same day as the Salerno landings, troops of the British 1st Airborne Division were to be put ashore from several cruisers in the harbor of Taranto and nearby Brindisi on the “heel” of the Italian peninsula. Taranto would provide a major port for resupply and, after Taranto was secure, these troops were to move up the eastern coast and take the airfields at Foggia.

The Salerno landing was code-named Operation Avalanche, while the Calabria landing was designated Operation Baytown and the attack on Taranto Operation Slapstick. British General Sir Harold Alexander was in overall command of XV Army Group ground forces, while Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham and Air Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder commanded sea and air operations.

Mark Clark and the U.S. Fifth Army

Clark’s Fifth Army consisted of both British and American units. The British contingent was X Corps, which included the veteran 46th and 56th Infantry Divisions, the 7th Armoured Division, and several Commando units. Tactical command of these forces was given to General Sir Richard L. McCreery when its original commander, General Sir Brian Horrocks, was wounded in an air raid. The American Fifth Army contingent was designated VI Corps and commanded by Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley. It included the 36th and 45th Infantry Divisions, with the 3rd and 34th Divisions held in reserve.

The choice of Clark to command Fifth Army was scrutinized by senior military officials, particularly since both Lt. Gen. George S. Patton and Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley had substantial combat experience. Both of these, however, were still engaged in the fighting in Sicily while planning for Salerno was under way. Patton’s infamous soldier-slapping incidents, which had occurred in Sicily, further discounted his potential for future command.

Eisenhower, a Clark fan, was prompted to write Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall that Clark was “the best organizer, planner and trainer of troops that I have met … the ablest and most experienced officer we have in planning amphibious operations…. In preparing the minute details of requisitions, landing craft, training of troops and so on, he has no equal in our Army. His staff is well trained in this regard. Clark impresses men, as always, with his energy and intelligence. You cannot help but like him. He certainly is not afraid to take rather desperate chances which, after all, is the only way to win a war.”

Clark expected to be in possession of Naples within five days, but the landing beaches and surrounding countryside at Salerno presented challenges of their own. While stiff German resistance was expected, the terrain around the landing zones included two rivers, the Calore and the Sele, which emptied into the Tyrrhenian Sea, creating a valley that split the low ground on the approaches to a series of imposing mountains. Artillery might play havoc with an invading force, and the Germans were sure to recognize this.

The beaches at Salerno were steep, which would allow landing craft to drop their ramps, emptying troops and supplies right onto them. Although Salerno was within the extreme limits of the range of Allied air support, an airfield at nearby Montecorvino could be captured and used. A rail line and coastal highway lay within reach of the beachhead, both extending through Naples and on to Rome, more than 130 miles to the northwest.

The Landings at Calabria and Taranto

Operation Baytown—Montgomery’s foray across the Strait of Messina—was to be the first of the three-pronged invasion. The timing of the Calabria landing was left up to Montgomery, who did not deem the situation appropriate until September 3. Eisenhower wrote that this was 10 days later than he had hoped.

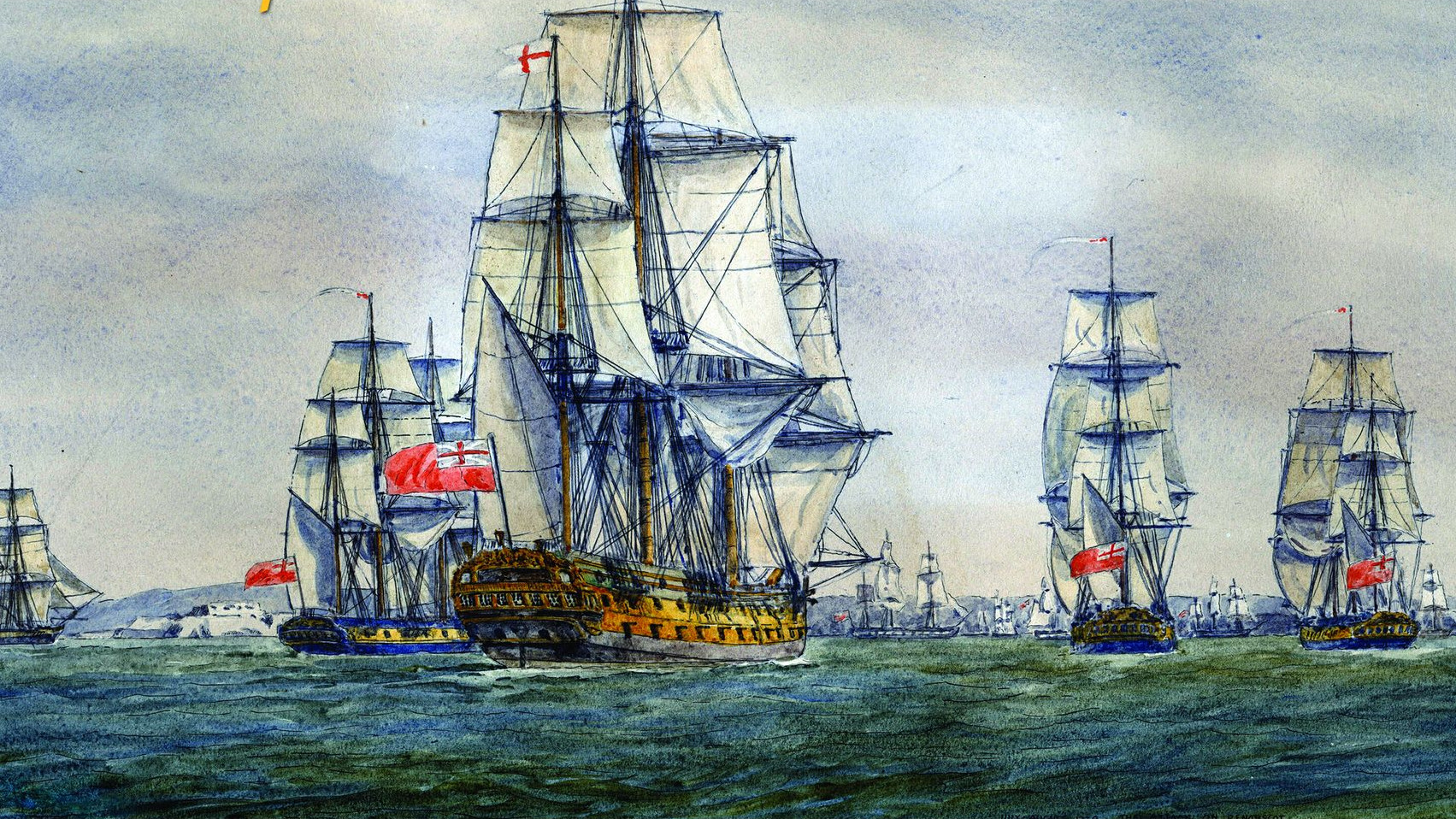

Considerable air bombardment of the intended Baytown landing area had taken place prior to September 3, and during the predawn hours of that day four Royal Navy battleships––HMS Warspite, Valiant, Rodney, and Nelson––raked the coastline with repeated salvoes. Destroyers, cruisers, gunboats, and three monitors armed with 15-inch cannons joined in. Eighth Army artillery, XXX Corps artillery, and four battalions of American artillery added to the total of 600 guns. Aircraft from bases in North Africa and Sicily supported the effort and attempted to hold the depleted Luftwaffe at bay.

The landings at Calabria were executed with virtually no opposition as Canadian troops of the Carleton and York Regiment and the West Nova Scotia Regiment splashed ashore. A few Italians appeared on the beaches and pitched in to help unload British landing craft. But Montgomery’s progress was, in the eyes of onlookers, both British and American, painfully slow. His forces did encounter difficult terrain and the delaying tactics that the Germans had honed to perfection in Sicily, blowing up bridges and creating landslides with demolition charges.

Montgomery’s penchant for perfection may have cost some of the initiative in southern Italy. The master of the set-piece battle, Montgomery may have been somewhat ill suited for a campaign that called for audacity and rapid movement.

Years later, author Alistair Horne in collaboration with Montgomery’s only son, David, wrote, “Once into mainland Italy, in September, the early performance of Monty and his Eighth Army was not much better [than it had been in Sicily]. Both were tired. The Americans, in their freshness, sometimes didn’t seem to appreciate what nearly four years of war, reverses and privations had done to their British allies. A huge preparatory barrage, Alamein-style, across the Straits proved unnecessary: the Germans had all withdrawn. Ambling leisurely northwards, Monty’s men found it ‘like a holiday picnic after Sicily and Africa’. Meanwhile, the US Fifth Army landings at Salerno, just short of Naples to the north, had run into serious trouble.”

Six days after Montgomery’s landing at Calabria, the troops of the British 1st Airborne Division came ashore at Taranto. Operation Slapstick was unopposed, and the harbor facilities were found to be in working order. The only major casualty was the minesweeper HMS Abdiel, which was sunk by a mine, killing 48 sailors and 101 soldiers.

Securing the Flank of the Salerno Beachhead

At the time of the Salerno landings, the 16th Panzer Division, commanded by Generalmajor Rudolf Sickenius, was the only fully equipped German armored division in southern Italy, and was well positioned to meet the invading force. With 17,000 troops, 36 artillery pieces, and over 100 tanks, 16th Panzer was quite capable of disrupting the landings. The Germans had also taken control of six coastal batteries at Salerno, which had previously been serviced by Italian crews.

At 3:10 am on September 9, less than half an hour ahead of the first wave of assault troops, the Rangers and Commandos came ashore to capture several key points on the northern flank of the Salerno beachhead, including the low ground along the approaches to Naples.

South of the gap created by the mouth of the Sele River, Maj. Gen. Fred L. Walker’s 36th Division, which included a large number of soldiers from the Texas National Guard, was to take the main roads leading in the direction of Montgomery’s Eighth Army and secure the right flank of the beachhead.

To the left of the 36th Division, the British 56th Division was to capture the Montecorvino airfield and the crossroads at Battapaglia. On the other side of the Sele, the 46th Division was to take the city of Salerno and maintain contact with the special forces to its left. Two regiments of Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s U.S. 45th Division were held in reserve. While the British chose to take advantage of a pre-invasion naval barrage, Walker opted to forego such a preparation.

Contesting the Skies and the Seas

Both the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy would play vital roles in the success of Operation Avalanche, just as they had in Sicily. At Salerno, Allied warships fired more than 11,000 tons of shells in support of the ground forces. In evaluating the performance of German forces that opposed the Allies at Salerno, General Siegfried Westphal, Kesselring’s chief of staff, acknowledged the contribution the Allied navies made. “But the greatest distress suffered by the troops was caused by the fire of ships’ guns of heavy caliber, from which they could find no protection in the rocky soil.”

The contribution, however, was not made without a price. Three American destroyers, the Rowan, Buck, and Bristol, were lost to torpedoes, along with a minesweeper, six LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank), and a fleet tug. The Royal Navy lost the hospital ship Newfoundland and five LCTs. Numerous other vessels were damaged.

Unlike during the later Operation Overlord––the Normandy invasion––ownership of the skies above the beachhead was bitterly contested. The resourceful Luftwaffe was still a formidable force and attacked the Allied armada with a vengeance. In addition to traditional ordnance, the Germans also employed radio-controlled glide bombs known as Fritz X, which many consider the ancestor of the modern cruise missile, and they wreaked havoc among American and British warships.

When the surrender of Italy was announced, the battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of the Italian Royal Navy––the Regia Marina––sailed to ports in North Africa or Malta and surrendered. Some were scuttled, but others were pounced upon by Italy’s one-time ally. For example, on September 9, a large battle group of eight cruisers, eight destroyers, and the battleships Roma and Italia (formerly the Littorio) that the Germans thought had steamed out of port to intercept the Allied invasion fleet, was actually heading for safe waters at Malta. The Luftwaffe swooped down on the group in the Strait of Bonifacio, inflicting heavy damage with Fritz X glide bombs and sinking the battleship Roma; more than 1,300 of her crew, including Admiral Carlo Bergamini, were killed.

“The Shells Almost Parted Our Hair”

When the British X Corps came ashore at Salerno at 4:45 am, opposition to the initial landing was relatively light. However, soon after the British units began to advance inland, Maj. Gen. Gerald W.R. Templer’s 56th Division was confronted by a force of German tanks that was beaten back with the help of naval gunfire from the destroyer HMS Nubian and warships of the Royal Navy’s Cruiser Squadron 15, which included HMS Mauritius, Orion, and Uganda, along with the monitor HMS Roberts, and several destroyers. The 56th Division sent probing attacks into Battapaglia and attempted to capture the Montecorvino airfield but was unable to do so.

Naval gunfire also threw back several counterattacks against the 46th Division, commanded by General J.L.T. Hawkes- worth. The destroyers HMS Blankney, Mendip, and Brecon added their fire against mobile batteries of German 88mm cannons. The 88mm could be used as an antitank, antipersonnel, or antishipping weapon, although it was originally intended as an antiaircraft gun.

Shortly after they came ashore, soldiers from the 9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers were fired on by a battery of German rocket launchers. The Fusiliers called for support, and a Royal Navy destroyer obliged. “The shells almost parted our hair,” remembered one of the Fusiliers. “The rockets were wiped out but a machine gun nest, spared in the barrage, had to be taken by the troops.”

The job of silencing the machine guns fell to Lieutenant David Lewis, who had already gained fame as a rugby player in Wales. Lewis was mortally wounded during the attack, but the machine guns were put out of action and 25 prisoners were taken.

Successive waves of Allied troops also encountered early and stiff resistance. The 141st and 142nd Infantry Regiments of the 36th Division came ashore on hotly contested beaches as knocked-out landing craft drifted ablaze near the shoreline. One 81mm mortar platoon waded in with its weapons but no ammunition because the boat carrying it had been blown up.

After moving inland only a short distance, much hard fighting swirled around a 50-foot-tall medieval stone tower that held a machine-gun nest. Pinned down, men of the 36th Division eventually knocked out the German position.

Heroism on the Salerno Beachhead

Individual acts of heroism were numerous that morning on the beaches at Salerno. Corporal Royce C. Davis used a bazooka to disable a German tank, then crawled close enough to the disabled vehicle to flip a hand grenade inside the hole his weapon had made. Pfc. Henry C. Harpel took the loose planking from a bridge and threw it into the water of an irrigation ditch so that approaching enemy tanks could not cross. Sergeant John Y. McGill dropped a hand grenade through the open turret of a German tank. Sergeant Manuel S. Gonzalez advanced toward a machine-gun nest, wriggled out of his pack, which had been set on fire by a tracer bullet, and blew up the position with a grenade.

Sergeant James M. Logan killed several Germans from a concealed position along an irrigation canal while they advanced through a gap in a rock wall 200 yards distant. He then crossed an open field, wiped out a machine-gun nest, and turned the German weapon on the enemy. For his daring exploits, Logan received the Medal of Honor.

One counterattack against the 36th Division by 16 German Mark IV tanks was scattered just before noon on the 9th by the concentrated 6-inch gunfire of the cruisers USS Boise and Philadelphia. Six of the tanks were destroyed and the remainder were ordered back out of range of the big naval guns.

The Germans managed to destroy a key bridge across the Sele River on Highway 18 and prevented the British and American forces from closing the gap between them on the first day. The Commandos were still separated from the left of the 46th Division, but the small force held the city of Salerno. The 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions destroyed a pair of German armored cars and claimed the high ground on both sides of the Chiunzi Pass, a commanding position above Highway 18, which was the best route over the rugged Sorrento Peninsula into Naples.

Clark knew that German reinforcements could be expected around Salerno and brought two regiments of the 45th Division ashore. Later, a drop by the 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division was ordered around Avellino on the 14th, while the third regiment of the 45th Division, elements of the 7th Armoured Division, and more airborne troops would reach the Salerno beachhead by September 15.

Montgomery’s Slow March to Salerno

On the evening of September 9, however, Montgomery was still over 120 miles from Salerno. His troops were exhausted by their march, and Montgomery paused on September 10 for 48 hours. He lamented the difficulties, writing later, “The roads in southern Italy twist and turn in the mountainous country and are admirable feats of engineering. They abound in bridges, viaducts, culverts and even tunnels, and this offers unlimited scope to military engineers for demolitions on the widest possible scale.”

Meanwhile, the men fighting for their lives at Salerno were fuming at Monty’s leisurely pace.

During the first 24 hours, the Allied beachhead was in jeopardy, with the 36th Division occupying an extended front and the British X Corps taking the brunt of the German counterattacks on September 10. The Commandos were fighting pitched battles with the parachute battalion of the Hermann Göring Division, while the Royal Fusiliers and the 167th Infantry Brigade at Battipaglia and Vietri, a mere 12 miles from Salerno, had lost 1,500 men taken prisoner.

Although the 16th Panzer Division had withdrawn from the immediate vicinity of the invasion beaches, Vietinghoff was convinced that the division had fought well. While it had not been strong enough to throw the invasion back into the sea, the landing force had been contained reasonably well thus far.

Additionally, the LXXVI Panzer Corps, which included the 26th Panzer Division and the 19th Panzergrenadier Division, was moving northward from Calabria as quickly as possible, while the 15th Panzergrenadier Division and the Hermann Göring Division, though roughly handled in Sicily, had been reconstituted and were positioned north of Naples.

Stiff German Resistance

The battle raged on land and sea for days. On September 11, the cruiser USS Savannah took a direct hit from a 660-pound Fritz X glide bomb on its No. 3 turret, causing such damage that the vessel settled by the bow until her forecastle was nearly at the waterline. With an escort of four destroyers, the wounded cruiser reached safety in the Grand Harbour at Malta.

On the afternoon of September 13, another radio-controlled bomb hit the cruiser HMS Uganda, penetrated seven decks, exploded, and damaged the ship so severely that she took on 13,000 tons of water before a U.S. Navy tug took her in tow. The battleship HMS Warspite was hit by two of these innovative weapons and shaken by two near misses three days later.

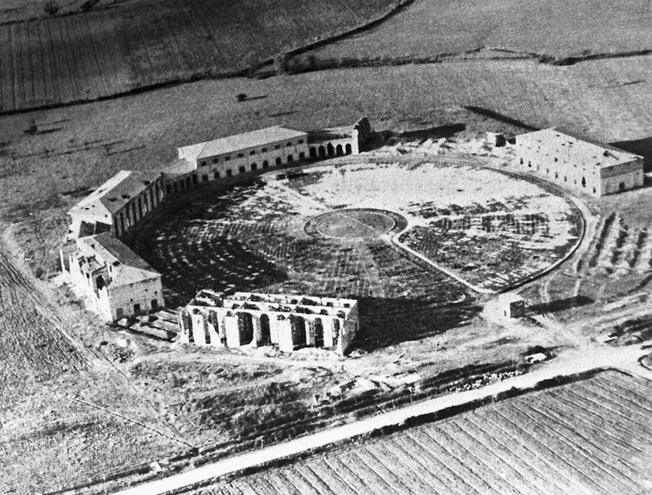

On September 11, two offensive efforts were mounted against the high ground at Eboli and Altaville, commanding both sides of the valley of the Sele and Calore Rivers. Moving against Eboli, two battalions of the 157th Regiment, 45th Division, were joined by a platoon of the 191st Tank Battalion. Just west of Persano, as the Americans approached a complex of five buildings arranged in a semicircle and known as the tobacco factory, a battalion of the 16th Panzer Division, ordered back from Battipaglia, was waiting.

When the Americans were within a few yards, the Germans sprang their ambush, fire erupting from a nearby rail line, positions along a parallel roadway, and the buildings. Seven American tanks were quickly out of action. The troops of the 157th were forced to dig in four miles short of Eboli while the buildings of the tobacco factory remained in German hands.

Another regiment of the 45th Division, the 179th, sent two battalions straight for Ponte Sele, while the third battalion guarded the right flank of the advance toward Hill 424 and Altaville. German artillery and small-arms fire hit the Americans before they reached Ponte Sele, and for a time the crossing of the Calore River appeared doubtful. Had the Germans captured the crossing site, the American infantry and armor might have been cut off. The two battalions from the 179th occupied defensive positions near Persano, four miles from Altaville.

The flank battalion of the 179th drove on with a platoon of the 190th Tank Battalion and the 160th Field Artillery Battalion, only to be stymied by further German resistance before retiring to defenses along La Cosa Creek. Ironically, the 36th’s 142nd Infantry Regiment managed to occupy both Altaville and Hill 424 against little opposition. The following day, a ferocious German counterattack dislodged the 142nd from its position, which was the most forward and exposed of any along the VI Corps perimeter.

Confident German Counterattacks

Vietinghoff’s confidence in his ability not only to drive the invasion force into the sea but to cut off its escape had grown steadily. By the afternoon of September 13, the 29th Panzergrenadier and 16th Panzer Divisions launched a devastating attack while elements of the 36th Division were attempting to retake Altaville. The American attack fell apart, and small groups of infantrymen were forced to thread their way back to their lines after dark. Three soldiers, Corporal Charles Kelly, 1st Lt. Arnold Bjorklund, and Private William J. Crawford, later received the Medal of Honor for their part in this heavy fighting.

Some confusion existed among American commanders as to the defensive positions covering the Sele-Calore valley. The head of the corridor was, therefore, thinly defended. The Germans at LXXVI Panzer Corps headquarters were convinced that the Allies were evacuating. As the afternoon wore on, German attacks grew in intensity, and scores of tanks and infantry roughed up a battalion of the 157th Regiment before hitting the 143rd Regiment on both flanks and taking 500 prisoners.

By 6:30 pm on September 13, German tanks were within two miles of the beaches, with only two American field artillery battalions and a firing line of cooks, clerks, musicians, and walking wounded opposing them; the Fifth Army command post stood only a few hundred yards behind and Clark made plans to evacuate on as little as 10-minutes’ notice. The artillerymen poured 4,000 shells into enemy lines and finally stopped the German attack.

A historian commented, “The only troops who stood between the Germans and the sea were some supporting artillery of the 45th Division. These guns saved the day and quite possibly the battle.”

The invasion had come within an eyelash of disaster.

On September 14, German attacks were much less productive. Clark had consolidated and shortened his line during the night, and the combined artillery of the 45th and 36th Divisions fired over 10,000 rounds. Heavy bombers, diverted from missions against targets in Germany, added support. One tank destroyer of the 636th Battalion knocked out five German tanks and a truck filled with ammunition in 30 minutes. Altogether, 30 German tanks were destroyed. The VI Corps line had almost miraculously held.

Fighting continued at Hill 424 and Altaville, and one American soldier remembered, “Darkness was falling as we began to climb the foothills, shells screaming over us … each explosion covering us with dirt and rocks. I’d never known real terror until that moment…. Cadavers of men from previous attacks lay scattered all over the hill. It was a horrible experience for us to see these countless dead men, many of them purpled and blackened by the intense heat.”

Vietinghoff also struck back hard at the British on September 13 and 14, his armor hitting the 56th Division southeast of Battipaglia. The Coldstream Guards, Royal Fusiliers, and infantrymen of the 167th Brigade were bolstered by heavy naval and air support and beat back the attack.

Peter Wright’s Victoria Cross at Salerno

A few days later, Company Sgt. Maj. Peter Wright took command of his company of the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards, after all of its officers had been killed or wounded. Wright destroyed three machine-gun nests with hand grenades, relocated his company to a more favorable position, and captured important high ground. The action earned Wright the Distinguished Conduct Medal, but a year later King George VI ordered the medal upgraded to the Victoria Cross.

Private Ernest Hulse of the Durham Light Infantry exhibited conspicuous courage on the 15th and 16th when he evacuated wounded from a hillside north of Salerno. “It is fair to say that he was responsible for evacuating some 30 casualties … and the majority of them under fire,” wrote Lt. Col. J.C. Preston, commander of the 16th Battalion. Captain Frank Duffy, commanding a company of the Durham Light Infantry on the evening of the 15th, organized a bayonet charge and counterattacked the Germans along the crest of a hill, killing 15 enemy soldiers and capturing 11.

After more than a week of tough fighting, it was clear that the Allies would not be dislodged from their clawhold on the Italian mainland and that the war was about to enter a new phase.

“General Clark Had Everything Under Control”

While the presence of Montgomery’s Eighth Army, still moving up from the south, was sufficient to cause concern for the Germans and to at least present them with the necessity of prioritizing their defensive assignments, the crisis at Salerno had passed by the time Monty’s troops made contact with the Fifth Army. Reinforcements from the VI and X Corps reserves bolstered the beachhead at Salerno, and both corps forged inland. On September 18, Vietinghoff realized that the game was up and directed his forces to withdraw northward to the Apennine Mountains.

Montgomery’s chief of staff, General Francis “Freddy” de Guingand, wrote, “Some would like to think—I did at the time—that we helped, if not saved, the situation at Salerno. But now I doubt whether we influenced matters to any great extent. General Clark had everything under control before Eighth Army appeared on the scene.”

“See Naples and Die”

The Allied victory did not come cheaply. In more than a week of desperate fighting, the British X Corps had lost over 5,500 casualties. The U.S. VI Corps had lost 3,500, with 500 killed and 1,800 wounded. One other casualty of Operation Avalanche was Maj. Gen. Dawley, the VI Corps commander. Some believed he had become unnerved by the strain of combat command, while others were surprised that he had been relieved by Clark on September 20; a telephone conversation with Dawley at the height of the fighting had left the Fifth Army commander concerned.

Eisenhower may have decided that the exhausted Dawley should be relieved before visiting the VI Corps headquarters himself. The official history of the U.S. Army in World War II relates, “When Eisenhower, Clark, Dawley, and Admiral [Kent] Hewitt visited his 36th Division command post and received a briefing from [General] Walker, the division commander had the feeling that Eisenhower was paying little attention to his words. At the end of Walker’s presentation, Eisenhower turned to Dawley and said, ‘How did you ever get your troops into such a mess?’”

On September 29, Marshal Badoglio met Eisenhower aboard the battleship HMS Nelson and signed the formal surrender document. Even so, the agony of Italy was far from over.

All the speculation about what should or could have been done at Salerno was hindsight as September began to wane. Months of difficult fighting lay ahead in Italy at places like San Pietro, the Rapido and Volturno Rivers, Cassino, Anzio, and the northern Apennines. The hard-won success of the first major landings by Allied troops on the continent of Europe would be followed by an excruciating northwestward drive. The old phrase, “See Naples and die,” was destined to take on an ominous significance.

Thank you for all of the great reporting.