By Steve Lilley

In the 1939 movie The Real Glory, elite U.S. Army officers arrive in the southern Philippines to mold the Filipinos into a military force to defend their villages against marauding Moro tribesmen. In one scene, a burly, sword-wielding Moro attacks the Army unit’s commander. The Moro charges through a hail of lead unleashed by other officers, including Dr. Bill Canavan (Gary Cooper), and fatally wounds the colonel before succumbing to the gunfire.

Later, Canavan drops five spent bullets from the Moro’s body on a table in front of his fellow officers and the parish priest. “I thought I missed when I shot at that juramentado, but I guess I didn’t,” Canavan said. “He had enough lead in him to sink a battleship. I wonder what kept the beggar going with all those slugs in him. Must be some drug.”

The scene was realistic. During the Army’s early years in the Philippines, such incidents created a crisis of faith among U.S. soldiers—faith in their weapons. That crisis led the Army to adopt one of the most famous firearms in history, the 1911 Colt, but the outcome might have been very different. Generations of American soldiers might have gone into battle with 1907 Savages instead.

The Need For Increased Stopping Power

The trouble began in 1899. When the United States won the Spanish-American War and annexed the Philippines as a colony, it unexpectedly entered a conflict more costly, longer, and deadlier than the war with Spain had been. The Moro tribesmen of the southern Philippines proved especially difficult to subdue. Fiercely independent, fanatical, courageous in battle, and predatory, the Moros had never submitted to the Spanish and proved no more willing to accept their new American overlords.

A shortage of American troops at the onset of the Philippine insurrection in 1899 delayed a showdown between the U.S. Army and the Moros, but once Emilio Aguinaldo’s rebel forces surrendered in 1901, the Americans moved to deal with the Moros. After diplomatic efforts to conciliate the Moros failed, U.S. troops quickly bested them in open battle.

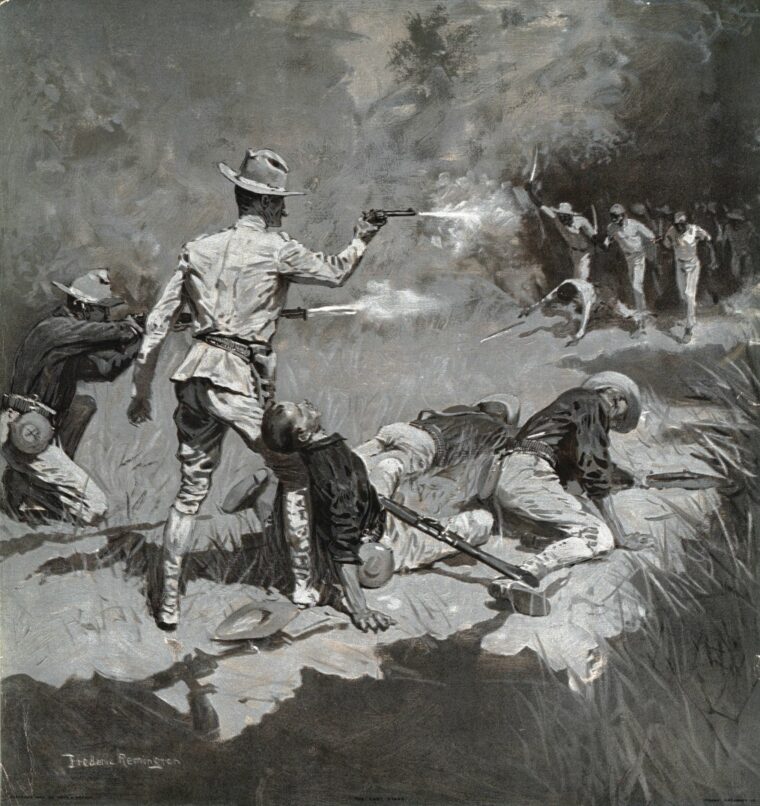

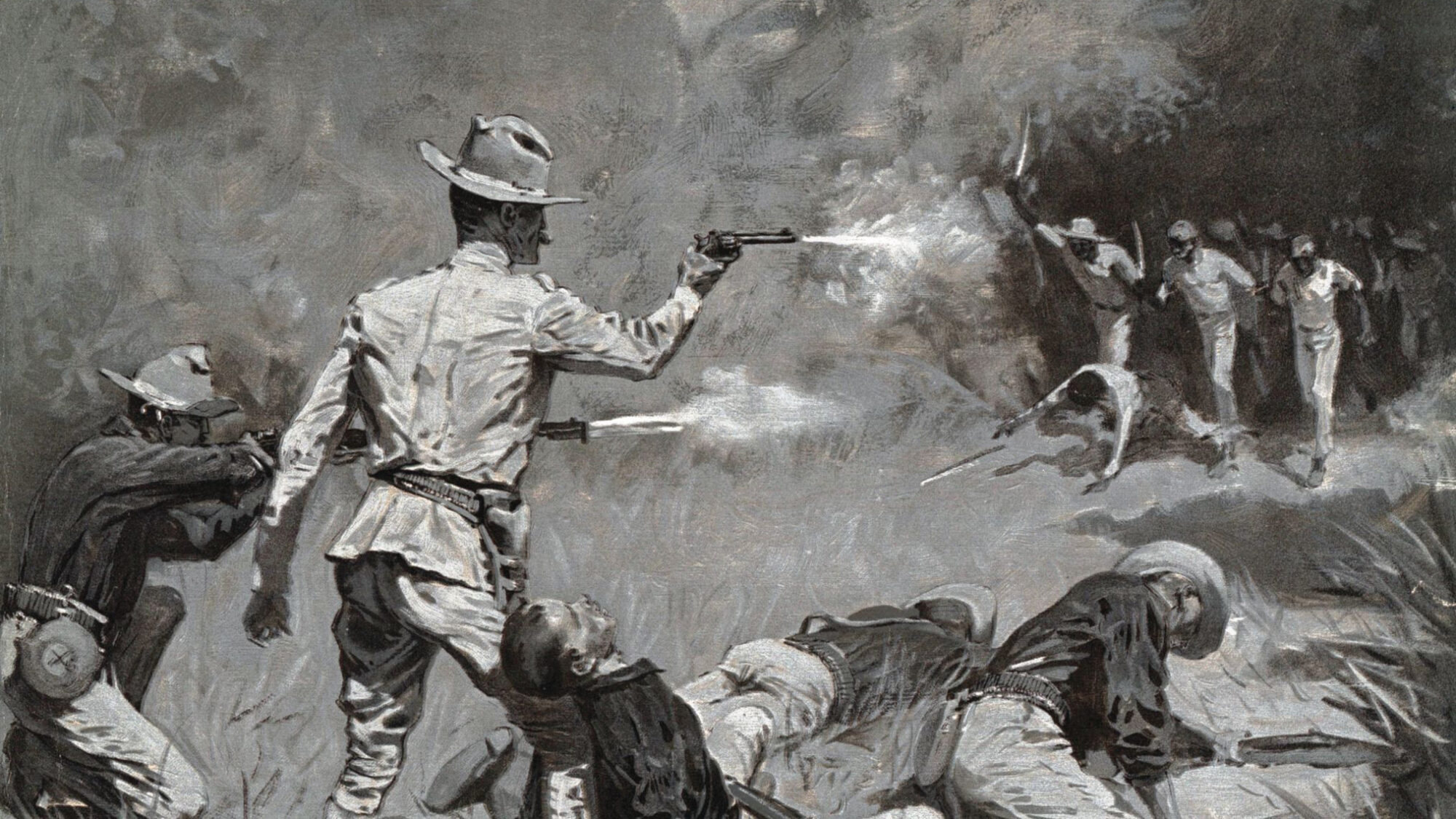

Unable to defeat the Americans in conventional combat, the Moros resorted to juramentado attacks, a tactic modern military analysts call “asymmetrical warfare.”

Using edged weapons, juramentados attacked and killed American officers. The Moros’ remarkable ability to absorb gunfire and their fanatical determination to kill their victims unnerved American soldiers much as it had the Spaniards. The juramentado might shout, “There is no god but Allah!” as he charged, giving the targeted officer time to draw his service revolver and fire on his attacker, but often the juramentado, due in part to an adrenalin rush and special preparations to slow blood loss, died of his wounds only after killing his victim.

As such incidents mounted, soldiers cursed their standard issue 1892 Colt New Army revolvers and the .38-caliber Long Colt cartridge they fired. Like most Western nations, during the late 19th century the United States adopted smaller caliber weapons for its military small arms. Then current wisdom held that smaller projectiles traveling at higher velocities would inflict at least as much damage on a target as slower moving, larger caliber bullets, while imparting less recoil and enabling soldiers to fire more accurately.

While the 1892 double-action Colt revolver with its swing-out cylinder fired and reloaded more quickly and weighed less than the single-action Colt 1873 revolver it replaced, it also fired a projectile less than two-thirds the weight of the 1873’s .45-caliber Long Colt cartridge. Worse still, the .38 Long Colt delivered little more than half the energy of the .45.

American soldiers did not require technical explanations for the .38 Long Colt’s inadequacies. They observed the results firsthand in combat. Army Colonel Louis A. LaGarde described one such incident. In October 1905, a Filipino named Antonio Caspi escaped from a prison on the island of Samar. During the escape, soldiers fired on Caspi with their New Army revolvers. Three .38 Long Colt bullets fired at close range struck him in the chest, penetrating his lungs. A fourth wounded his hand and forearm. Still, Caspi remained unsubdued until a soldier felled him with a blow to the head from the butt of his carbine.

The Thompson-LaGarde Tests: “A Caliber Not Less Than 0.45”

Long before the Philippines, the Army knew it needed more effective small arms, and its search for a better military handgun had already begun. The Spanish-American War revealed the Army’s rifles and side arms were less effective and less modern than their European counterparts. In 1900, the Army ordered 1,000.30-caliber Lugers from Germany and 475 Colt model 1900 semi-automatic pistols and issued them to U.S. Cavalry units for field testing. The Swiss Army had adopted the Luger as its military pistol in 1900. Germany’s army and navy would soon follow suit, but the .30-caliber Luger didn’t impress American cavalrymen. During the late 19th-century Indian wars, the cavalry carried most of the burden of combat, relying heavily on their side arms. The elegant, small-bore Luger did not strike the experienced horse soldiers as an adequate man-stopper.

As an emergency measure, the Army reissued the old 1873 Colt single-action revolvers to its soldiers. The Army also ordered 4,600 double-action 1902 Colt revolvers, also called the Philippine Constabulary or Alaskan Models, which were Colt Model 1878 revolvers redesigned to chamber the .45-caliber Long Colt cartridge, as a stopgap handgun. The year before the Caspi episode, LaGarde had already concluded that American soldiers needed a more potent sidearm.

In 1904, LaGarde, a surgeon in the Army’s medical corps, presided over a series of tests to determine the optimum caliber and configuration for a military pistol or revolver. Working with Captain John T. Thompson, who later invented the Thompson submachine gun, the team tested the lethality of various weapons. The Thompson-LaGarde tests were controversial, with some critics contending that the team had rigged the tests to support their preference for a large-caliber handgun. The team also fired bullets into human cadavers and live horses and cattle, practices some found objectionable.

However valid its scientific techniques, the team reported its findings in no uncertain terms: “After mature deliberation, the Board finds that a bullet which will have the shock effect and stopping power at short ranges necessary for a military pistol or revolver should have a caliber not less than 0.45.” The report called for improved marksmanship training, insisting that “soldiers armed with pistols or revolvers should be drilled unremittingly in the accuracy of fire, and that the vital parts of the body, their location, and distribution should be intelligently explained.” It was good advice, but the Army focused on the common-sense conclusion the soldiers had already reached. They needed a pistol firing a bigger bullet.

Colt, Luger, and Savage

With the Thompson-LaGarde tests in mind, the Army invited arms manufacturers to participate in a practical competition to be held in 1906 to select a replacement for the Colt New Army revolver. Only a handful of companies— White-Merrill, Knoble, Bergmann, Deutsche Waffen und Fabriken Munitions (the manufacturer of the Luger), Webley, Colt, and Savage— submitted entries. Following European military trends, most of the test weapons were semi-automatic handguns.

Before the tests began in earnest, the Army rejected most of the entrants as unsuitable and focused mainly on the Colt, Luger, and Savage pistols. After some delays, the pistol trials began in January 1907. From the beginning, Colt’s entry enjoyed an advantage. The Colt Company had existed since 1848 and had supplied revolvers to the Texas Rangers, U.S. Army, and U.S. Navy since the Civil War. From the 1870s into the 20th century, Colt’s 1873 Single Action Army and New Army models equipped the U.S. Army.

The handguns Colt submitted to the Ordnance Board following the Spanish-American War were designed by the greatest creative genius in firearms history, John Moses Browning. Under Browning’s guidance, Colt first offered its semiautomatic pistol to the Army in 1900 and constantly supplied improved versions to meet the Army’s evolving requirements. In 1905, when the Army complained that the .38 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) cartridge would not suffice, Colt quickly developed the .45-caliber ACP cartridge and supplied an improved pistol chambered for it. Colt had the experience, brains, resources, and determination to win the Army’s next sidearm contract.

Savage Model 1907: An Art Deco Handgun

Colt’s upstart American challenger seemed a long shot at best. The Savage Arms Company had come into existence only 13 years prior to the Ordnance Board trials. Its founder, Arthur Savage, had designed an advanced lever-action rifle that eventually would become the classic Savage 99. When in 1892 the U.S. Army sought a replacement for its trapdoor Springfield rifles, Savage submitted his modern, eight-shot lever action, but the Army adopted the 1892 Krag-Jorgensen bolt-action rifle instead.

When the pistol trials began, not only had Savage Arms never sold a weapon to the Army, it had never produced a pistol. Seeing the commercial success that Colt’s semi-automatic pistols enjoyed, and the prospect of a lucrative government contract, Savage decided to enter the market. Inventor Elbert Searle provided the design the company needed. Searle had designed and held the patent for the 1907 Savage. His pistol came to Savage Arms’ attention just in time to provide the company a credible entrant into the Ordnance Department’s 1906 pistol trials. Scrambling to perfect and produce a sample handgun for the trials, which the Army had rescheduled for January 1907, Searle completed the first 1907 Savage just under deadline.

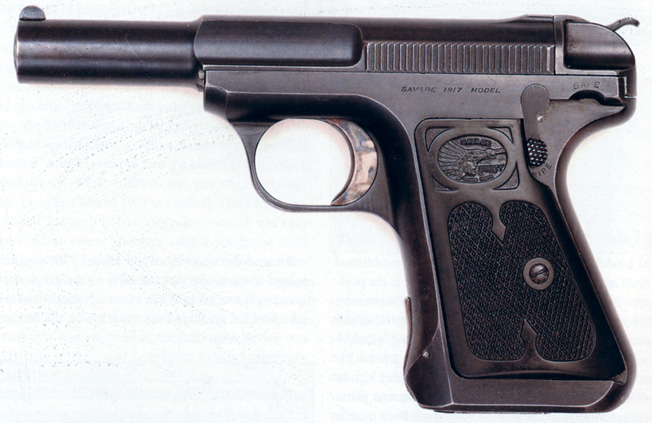

The result was a handsome weapon. Sleek and beautifully finished, the 1907 Savage was described by some as an art deco handgun. The innovative design employed no screws except those retaining its grips. Not only could a soldier easily disassemble the weapon without tools, but the disassembled pistol contained only 34 component parts, fewer than its Colt competitor. Unlike most other semiautomatic handguns, the 1907 used no flat springs, relying instead on more robust coil springs. The Savage used a staggered-round box magazine—the first commercially produced pistol to do so—giving it a maximum nine-shot capacity, one more than the Colt’s single-stacked magazine.

Recognizing that the winning entrant would equip cavalry troopers, Searle even built a cleverly designed folding lanyard loop into the 1907’s magazine well. Savage Arms Company had produced an impressive challenger to the Colt in a remarkably short time.

Savage vs Colt: Fighting For the Military Contract

However promising the Savage, Colt, and other pistols looked, the Ordnance Board did everything in its power to uncover their weaknesses. One test involved blasting each pistol with fine sand for one minute. After this treatment, the tester blew and brushed the sand off the pistol and fired it to assess its reliability. In another torture test, each handgun was degreased, its barrel plugged, and the weapon immersed in a corrosive solution for five minutes. Another reliability test followed. The Savage bested both the Luger and the Colt in the sand test and delivered projectiles at a higher velocity than either.

After the first tests, the Ordnance Department concluded that the Luger, Colt, and Savage pistols merited further testing. The newcomer, Savage, had acquitted itself well and remained in the running for a sizable military contract, but this success presented fresh difficulties. After each round of tests, the Ordnance Department requested design improvements. An early competitor in the process, Colt, blessed with deep pockets, continually incorporated the changes into its evolving design. The Ordnance Department informed Savage that it wanted the front sight moved rearward, the ejection port relocated, and a grip safety added.

The Army offered contracts to Luger, Colt, and Savage for 200 of the improved pistols to undergo field trials with active-duty units. The manufacturers would receive $25 per copy. Colt quickly agreed to fill the contract at that price. Georg Luger apparently suspected that the U.S. Army had little interest in a European design for its next sidearm, and politely declined the offer. The .45-caliber ACP Luger became an extremely rare collector’s item.

Savage Arms considered the military project risky, expensive, and time-consuming, but the company saw growing potential for a smaller-caliber civilian version of Searle’s 1907. When, in October 1907, the Army agreed to pay $65 for each of the .45 ACP 1907s, Savage relented and signed a contract to produce the test pistols. Savage may have committed to the next phase of the competition because a military contract would help the company retrieve expenses it incurred tooling up to produce its Commercial .32-caliber ACP pistol. As efficient as this may have seemed, Savage’s commercial development of the .32-caliber model may have diverted its limited resources from the military competition.

Unlike Savage, Colt made the military contract its top priority. The Army clearly intended to replace the company’s 1873 Single Action Army and New Army revolvers, and Colt long arms generated little revenue. Colt realized that its success depended on selling semi-automatic handguns to the Army’s Springfield, Massachusetts, armory. By March 1908, the Army received 200 sample Colts.

Savage produced its first sample .45-caliber 1907s a month and a half after Colt filled its contract. The sample 1907s did not arrive until November, and then the shipment fell short by five handguns that had mysteriously disappeared in transit. Within a month, Savage replaced the five missing pistols. The trial pistols received mixed reviews. Captain James A. Cole of the 6th Cavalry said the Savage had “a splendid grip, is easily and rapidly pointed, has tremendous powers and is very accurate,” but still judged that it was unsuited for issue in the military service. Soldiers complained of malfunctions and said the Savage recoiled excessively.

The Army rejected and returned the entire shipment because the Savage 1907 lacked “safe” and “fire” markings for its safety lever. Such an omission would have created dangerous problems with troopers unaccustomed to semiautomatic handguns. Pistol gremlins intercepted the 1907s before they reached Savage’s Utica, New York, plant, and 72 more of the weapons disappeared. The Army made it clear to Savage that the missing pistols were the company’s responsibility.

The 6,000-Round Field Trial

In March 1909, the Army finally received 200 Savage 1907s modified according to its specifications. Field trials of both the Colt and the Savage began shortly thereafter. Cavalry troops in Georgia, Iowa, and New Mexico issued Savages to their skeptical horse soldiers. The new weapons appeared radically different from their familiar old revolvers, and breakages and parts failures in the Savages did nothing to inspire their enthusiasm.

The field trials did not satisfy the Army, which brought both competitors back to trials at Springfield in November 1910. Testers complained that the Savage imparted much heavier recoil than the Colt did. Savage addressed these issues by modifying the design, improving its sights, ejector, slide, and grips. While significant, these alterations fell short of Colt’s improvements. Like the Savage, Colt’s pistol incorporated a strengthened slide. Both companies added grip safeties, making accidental discharges of weapons unlikely. Just as importantly, John Browning modified his design’s operating system to increase both its durability and reliability. The significance of these changes would soon become apparent.

On March 15, 1911, the 1911 Savage faced the 1911 Colt in a marathon endurance test at the Springfield Armory. A large crowd of onlookers including Elbert Searle, John Browning, and the presidents of Savage and Colt watched as each pistol fired 6,000 rounds. While the Savage performed well through the first 1,000 rounds, Colt’s superior steel quality eventually gave Colt the edge. The 1907 suffered 31 failures and five part breakages. The 1911 Colt performed without failures or breakages of any kind.

Savage expert Bailey Brower, Jr., summarized the outcome: “The board’s choice was simple, and the Colt 1911 became the military’s automatic pistol of choice and one of the most popular firearms ever designed.” Nevertheless, the 1907 Savage had performed admirably. As historian Daniel K. Stern observed: “Much can be said for the Savage and its gallant stand. Without the stiff competition it offered Colt, the armed services would not have had as fine a gun as they eventually got, and this is a fact that is often overlooked.”

Finding Contracts With Portugal and France

Savage managed to salvage some of its investment in the military competition. It bought back the test pistols for $6.50 per copy and sold them on the commercial market. Today, these handguns are rare collectors’ items. Elbert Searle’s 1907 design enjoyed commercial success in civilian versions chambered for .32 and .380 ACP. Endorsed by Wild West legends Buffalo Bill Cody and Bat Masterson, these pocket pistols proved particularly profitable for the Savage Arms Company.

The outbreak of World War I finally resulted in military contracts for the 1907 Savage, but not for the U.S. military and not for the .45-caliber version. When the war began, France found itself short of weapons including officers’ side arms. Unlike their American counterparts, European officers’ pistols served much the same purpose as swords, acting more as symbols of rank than as combat weapons. The French military purchased approximately 40,000 Savage 1907s chambered for .32-caliber ACP, a caliber the United States Army considered wholly inadequate, but one that was widely used by European armies. The Portuguese Army procured an additional 1,150 .32-caliber 1907s.

Ironically, the 1907 Savage, a weapon that grew out of the need to give American soldiers more firepower, found favor with European militaries in part because of its small size and diminutive cartridge. In the end, these pint-sized Savages did go to war—just not in the hands of Americans.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments