By Don Duffy

By spring 1917, Russia had borne the heaviest burden of World War I. Russian reports counted more than six million men killed, wounded, or interned as prisoners of war. This enormous toll had bled the reserve pool of young Russian peasants nearly dry. The Russian Imperial Treasury was effectively bankrupt. Tsar Nicholas was forced to abdicate in March, but the new Russian Revolutionary Provisional Government continued the war against Germany. Its ability to raise morale, however, was scant. Bolshevik antiwar leaflets circulating among the Russian troops already had become one of the German High Command’s most effective weapons on its Eastern Front. Once blindly obedient to their hard-line elitist officer corps under penalty of flogging or death, hundreds of thousands of rebellious Russian soldiers lay down their arms and deserted or surrendered to the enemy they outnumbered. Desperation loomed. The major burden for regenerating the demoralized army fell on Minister of War Alexander Kerensky, a Socialist Revolutionary and silver-tongued orator whose chronic kidney disease exempted him from military duty. With Kerensky’s involvement, the roles of women in World War 1 were about to escalate.

In early summer 1917, Citizen Kerensky donned an unadorned khaki tunic, field cap, riding breeches, and army boots and set out for the front. Standing atop the hood of his open touring car to rally the troops while his general staff planned a renewed offensive, Kerensky earned himself the sardonic nickname of “The Great Persuader-in-Chief.”

“I am sent by the Revolution!” Kerensky would proclaim in his greeting to assemblies of skeptical soldiers. “Forward to the battle of freedom! I summon you not to a feast but to death!”

“For the sake of the nation’s life,” Kerensky recalled in his memoirs, “it was necessary to restore the army’s will to die.” One of his earlier official acts, however, had been his “Declaration of the Rights of the Soldier,” which banned punishment for disobedience and created committees of enlisted men to negotiate with ex-Tsarist officers who once commanded with whips and iron fists.

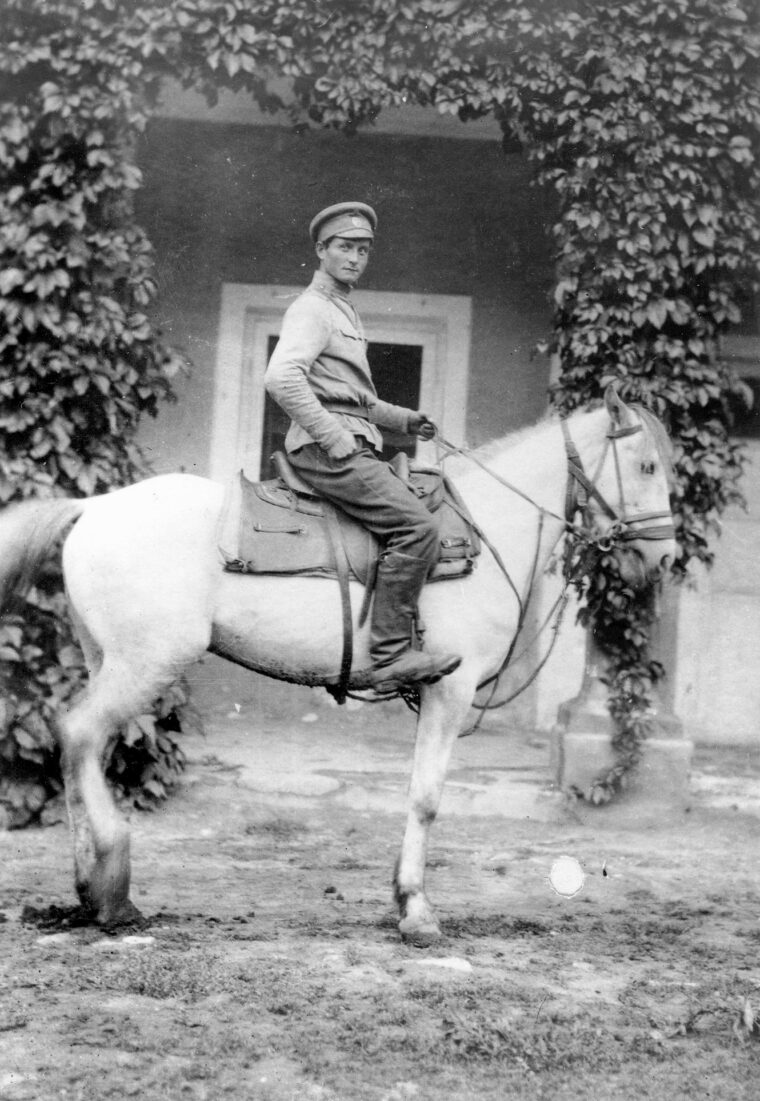

Uncounted numbers of Russian women already stood among the troops gathering to hear Kerensky’s orations, but at the time, the ways in which women could contribute to the war effort were often overlooked. Overworked and hard pressed to declare every draftee and volunteer fit for duty, Russian physicians had turned blind eyes to cross-dressing, shaven-headed women masquerading as men at their pre-induction physicals. Among these so-called Amazons crossing the gender line was Maria “Yasha” Botchkareva. A Siberian peasant, she’d fled from her drunken and abusive husband, enlisted in the Russian Imperial Infantry, suffered two wounds in combat, and won three decorations for bravery under enemy fire.

Organizing the Women’s Battalion

In May 1917, Duma (the Russian parliament) President Mikhail V. Rodzianko summoned Botchkareva to St. Petersburg to hear her plea for permission to organize a women’s battalion for the coming summer offensive. “You heard of what I have gone through and what I have done as a soldier,” Botchkareva stated to Rodzianko’s assembly of soldiers’ delegates to the Duma. “Now, how would it do to organize three hundred women like me to serve as an example to the army and lead the men into battle?”

Botchkareva attached one condition to her proposal. Unlike the new Revolutionary Army democratized by Kerensky’s decree, her battalion would respect the traditional discipline of the old Imperial Army. She would “exercise absolute authority and demand absolute obedience” from her volunteers.

Rodzianko sent Botchkareva to pitch her proposal to the new Commander-in-Chief (replacing the Tsar), General Aleksei A. Brusilov. The Duma president reasoned it would be easier for Botchkareva to sell her plan to Kerensky with Brusilov’s endorsement.

On May 15, 1917, accompanied by General Brusilov, Botchkareva pleaded her case to Kerensky at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. The Minister of War and future Prime Minister quickly grasped the potential of her proposal as a propaganda tool.

“I was granted authority then and there,” Botchkareva later recalled, “to form a unit under the name of the First Russian Women’s Battalion of Death.”

“Men and women citizens,” Botchkareva addressed the throng of war supporters gathered at St. Petersburg’s Mariynski Theater the following evening, “our mother is perishing! Our mother is Russia. I want to save her. I want women whose hearts are crystal, whose souls are pure, whose impulses are lofty. With such women setting an example of self-sacrifice, you men will realize your duty in this grave hour!”

Botchkareva claimed that 1,500 women in the audience applied for enlistment. That number swelled to more than 2,000 the following day after her speech at the Kolomensk Women’s Institute.

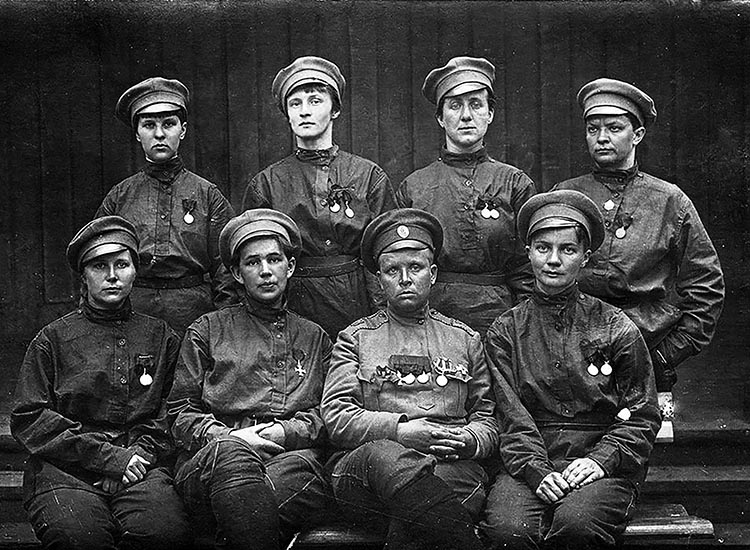

“There will be strict discipline and guilt will be severely punished,” Botchkareva laid down to the recruits, aged 18 to 35. “It is the purpose of this Battalion to restore discipline in the army.” She even demanded they sign a statement forfeiting their rights under Kerensky’s Declaration.

A Rigid System of Discipline & Training

British suffragette Emmaline Pankhurst witnessed and reported on the recruits’ basic training. Once a militant feminist at war with her government, Pankhurst had declared a truce on gender issues to concentrate on rallying women to the war effort.

“We apply the rigid system of discipline of the pre-revolutionary army, rejecting the new principle of soldier self-government,” the tough-minded Botchkareva told an Associated Press reporter who visited the battalion’s barracks on Torgvaya Street. “We impose a Spartan regime from the first. They sleep on boards without bed clothes, thus immediately eliminating the weak. The smallest breach of discipline is punished by expulsion in disgrace.”

The AP correspondent observed the women recruits marching “to an exaggerated goose- step,” carrying cavalry rifles five pounds lighter than the standard Russian infantry weapon. He encountered the wispy young daughter of the Tsarist-era Naval Minister standing sentry duty and the former editor of a feminist magazine serving as Botchkareva’s regimental clerk.

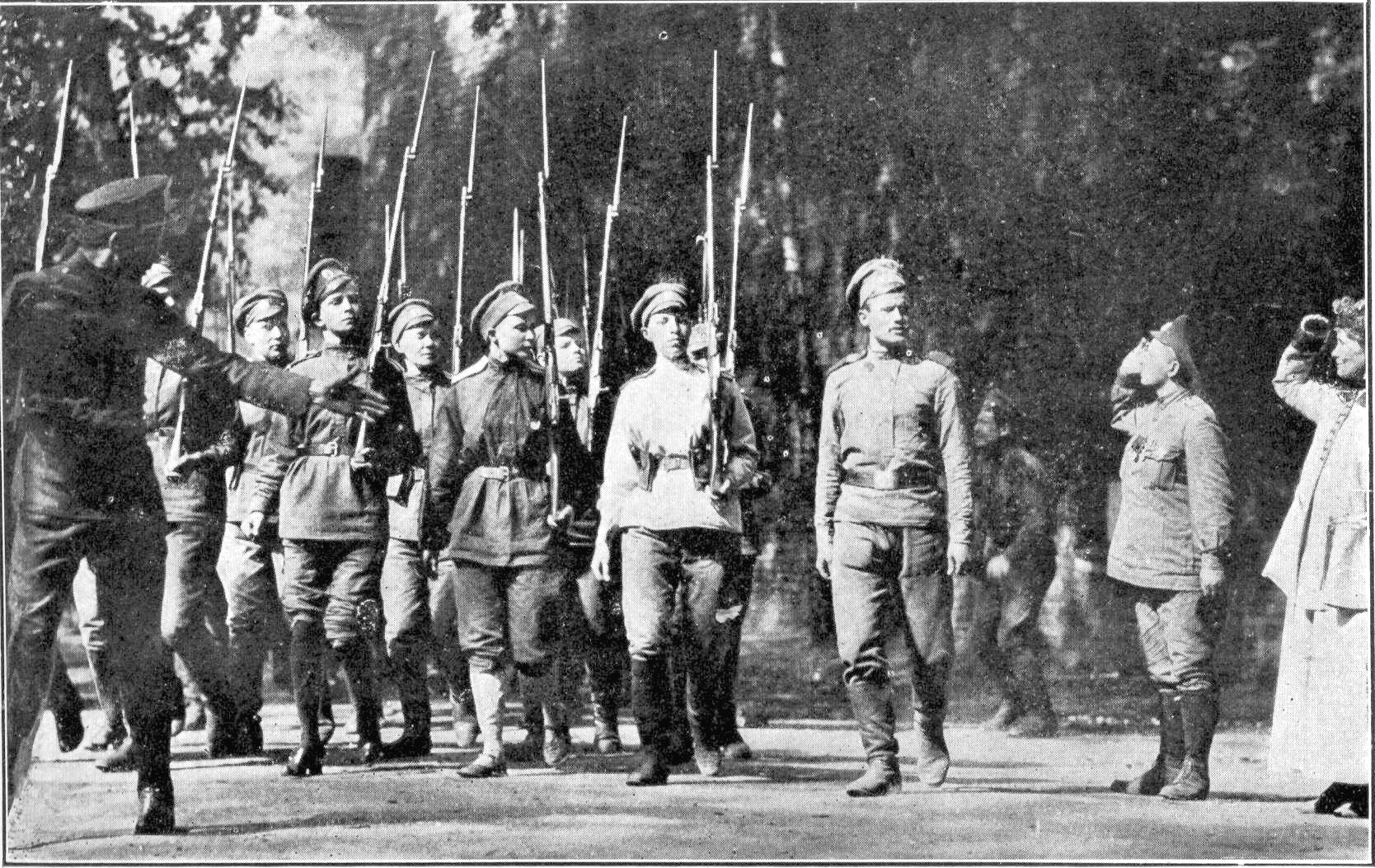

On July 7, 1917, their basic training completed and all their personal possessions confiscated except their brassieres, Botchkareva paraded her recruits into the square of Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg. There they knelt and received the blessings of an archbishop and patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Botchkareva carried a gold-handled saber presented to her by General Lar Komilov, soon to succeed Brusilov as Kerensky’s commander-in-chief. Her shoulders bore lieutenant’s epaulets pinned there by Kerensky himself. Like all her recruits, her head was shaved to its shiny skin.

Pankhurst, representing the international League for Equal Rights for Women; American Ambassador David Francis; British Ambassador Sir George Buchanan; and correspondents from the Associated Press and The New York Times were among the foreigners witnessing this patriotic event. Thousands of cheering spectators lined the battalion’s parade route to the station where they entrained for the front.

Lieutenant Botchkareva had one more hurdle to clear before leading her recruits in the first modern all-women’s assault on enemy troops. Kerensky ordered her to conform to his Declaration of the Rights of a Soldier.

“With two violent jerks,” Botchkareva later recalled, “I tore off my epaulets and threw them into the face of the War Minister.” She also claimed shouting: “I don’t want to serve under you!”

“Shoot her!” Botchkareva claimed the angry Kerensky shouted to the 9th Corps Commander. “Capital punishment has been abolished,” she quoted after her commanding officer’s retort. While some historians challenge Botchkareva’s account of that meeting at 9th Corps headquarters, several primary sources verify she prevailed in refusing to obey Kerensky’s demand.

Botchkareva’s unit took its position in the trenches of the 525th Kuraig-Daryuinski Regiment near the present Minsk-Vilnius highway. Artillery bombarded the German positions for two days in preparation for the Russian assault in the Battle of Smorgon. But when Zero Hour arrived, the enlisted men cowered in their trenches, debating whether to obey their officers’ command to go over the top.

According to Botchkareva’s account, 75 male officers and 300 of “the most intelligent and gallant” enlisted men pledged to follow her battalion in an infantry assault. “They’re faking!” she recalled a number of shirkers shouting until 300 women and 375 male followers climbed from the trenches to begin their trek across no-man’s-land.

“We moved forward against a withering fire of machine guns and artillery, my brave girls, encouraged by the presence of men on their sides, marching steadily against a hail of bullets,” the assault leader recalled. Their example stirred more malingering males into action. “First our regiment poured out and then, on both sides, the contagion spread and unit after unit joined in the advance.”

Smashing the German Lines

Botchkareva’s assault smashed the first and then the second German line. “But there was poison awaiting us in that second line of trenches,” she decried in her memoirs. The “poison” wasn’t mustard gas but caches of vodka and beer.

Hundreds of male attackers threw down their rifles, smashed open bottles, and began toasting their survival. Botchkareva ran along the trenches, ordering her women to destroy the stores of liquor and urging the men to follow her in an assault on the third German line.

Botchkareva and her surviving soldiers led the next assault. The enemy broke in retreat. The attackers took cover in a forest, retrieved their dead and wounded, summoned stretcher bearers, and sent out scouts to assess the situation while waiting for promised reinforcements from the 9th Corps reserves.

Those male reinforcements never arrived. A telegraph line sent word that the 9th Corps reserves remained huddled in the first line of Russian trenches, debating whether to obey their officers’ requests to advance.

Enemy artillery barrages signaled that a German counterattack was mounting. The telegraph line clattered a shocking decision. The men of the 9th Corps agreed to stand and defend their position against any counterattack but refused to advance from their trenches. The First Russian Women’s Battalion of Death had no choice but to retreat.

The collapse of the 1917 summer offensive spread across the entire front. On the Southwestern Front, General Anton Denikin gathered reports of regiments throwing down their weapons and fleeing in the face of savage enemy counterattacks. “I would say we no longer have an army!” he wrote in his report to Brusilov.

Botchkareva claimed that a concussion from a German artillery shell knocked her unconscious during the retreat. She recalled awakening in a field hospital and receiving reports of at least 50 of her “girls” among the dead and wounded in the Battle of Smorgon.

Eyewitness accounts of this first modern case of women in combat give Botchkareva’s “girls” mixed reviews for their performance and effect on male morale, depending on the observer’s gender bias.

Undying Fame & Highest Morale

British suffragette Pankhurst sent a proud but terse telegram to the editor of Brittania, reporting, “First Women’s Battalion number 250 took place of retreating troops. In counter-attack made one hundred prisoners including two officers. Only five weeks training. Their leader wounded. Have earned undying fame, morale effect great. More women soldiers training, also marines.”

British Red Cross nurse Florence Farmborough reported finding three of Botchkareva’s wounded “girls” in a field hospital. “At dinner,” she recalled, “we heard more of the Women’s Battalion of Death … they did go into the attack, they did ‘go over the top.’”

Belorussian observer B. Kamenshchykau confirmed that the Women’s Battalion led the charge but dismissed their impact on male morale. “The soldiers demanded that Botchkareva’s battalion should go over the top first. How great was the pleasure of the soldiers when, after the first artillery rounds from the Germans, the famed battalion broke off their attack.

With cries and screams, the ‘gallant’ women soldiers scattered among the bushes, and the soldiers had to search them out of the woods.… After that the soldiers declared that they would not go on the offensive, for if the screams of Botchkareva’s ‘gallant’ battalion could not break the German defenses, then it was obviously beyond the strength of simple soldiers like ourselves.”

The official Russian military report confirms the Battalion’s participation in the assault on the German trenches: “The party of wounded in the battles in the direction of Vilno report the extreme ferocity of the Germans, who preferred death to capture. . . . The field of battle was littered with German corpses. The women’s battalion, which received its baptism of fire, also suffered. The wounded women soldiers have been conveyed to Minsk.”

Other eyewitness accounts reported incredulous German prisoners cursing in shame and embarrassment after discovering they’d surrendered to women.

Botchkareva claimed her hospital visitors included the new Commander-in-Chief General Komilov, Kerensky, and a male delegate from the 9th Corps Committee bearing a testimonial to her bravery signed by all its members. After returning to the front, she found that “fraternization was general. There was a virtual, if not formal, truce. The men met every day, indulged in long arguments, and drank beer brought by the Germans.”

She claimed her exhortations to renew the offensive provoked many males into threatening her life. Promoted to the rank of captain, Botchkareva finally negotiated an agreement with her male harassers: “We will leave you alone, and you leave us alone.”

Civil Unrest in Russia

The commanding officer of the First Russian Women’s Battalion of Death was leading her “girls” in another assault when joyous news reached the men lingering in the trenches. The Bolsheviks had seized power in St. Petersburg. Kerensky, last Prime Minister of the Provisional Government, had fled for his life. A drunken mob of male troopers celebrated by seizing 20 of Botchkareva’s “girls” remaining in reserve and lynching them.

Botchkareva led her survivors from one demoralized command post to another, dodging male Bolshevik deserters threatening to execute her as a traitor to the cause for peace. Finally she agreed to disband her battalion for their own safety and headed for her home village near Tomsk, across a land Russian poetess Zinaida Gippius described as now bloodied by “Civil War without mercy.”

Botchkareva claimed she spied for General Kornilov’s White Guards along her journey, fell prisoner to a band of Red Guards, and barely escaped execution. An Associated Press dispatch from Archangel puts her in that northern Russian outpost in late December for a meeting with General Marushewski, Commander-in-Chief of the Northern White Guard.

This AP report states Botchkareva called on the general in full dress uniform, ready for combat in the anti-Bolshevik cause, only to be ordered to demobilize.

Heading to America

“I do not take the responsibility of estimating the merits of Mme. Botchkareva’s organization in the Russian Army,” the general’s official statement declared, “and I surmise that the efforts made and blood shed in the name of the Fatherland will be duly considered by the Central Government and by history.… I believe that the performance by women of military duties, which are improper for the sex, is a shameful mark stamped on the entire population of the region.”

This rejection by a male anti-Bolshevik leader persuaded Botchkareva to join the White Russian self-exiles directly pleading their case for foreign intervention. She entered the hordes of refugees heading for Vladivostok, the Russian Far Eastern port where Allied troops kept the peace while their ships awaited streams of evacuees.

On April 18, 1918, Botchkareva boarded the Sheridan, an American passenger liner. Her presence aboard ship is verified by Florence Farmborough, a fellow evacuee who wrote in her diary, “By a strange working of fate, one of the first persons I have seen on board is Yasha Botchkareva, erstwhile leader of the Women’s Death Battalion. She has eluded the spy-net of the Red guards and is making good her escape to the United States.”

If Botchkareva’s notoriety didn’t precede her to her adoptive country, her memoirs published in early 1919 soon vaulted her into temporary celebrity status. A New York Times dispatch reported President Woodrow Wilson receiving her at the White House on July 10 during his deliberations over the question of further American intervention in the Russian Civil War.

Maria Botchkareva returned to Russia in August to join the fight against the Bolsheviks, but was captured and executed in May 1920. She was 30 years old.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments