By Jared Frederick & Erik Dorr

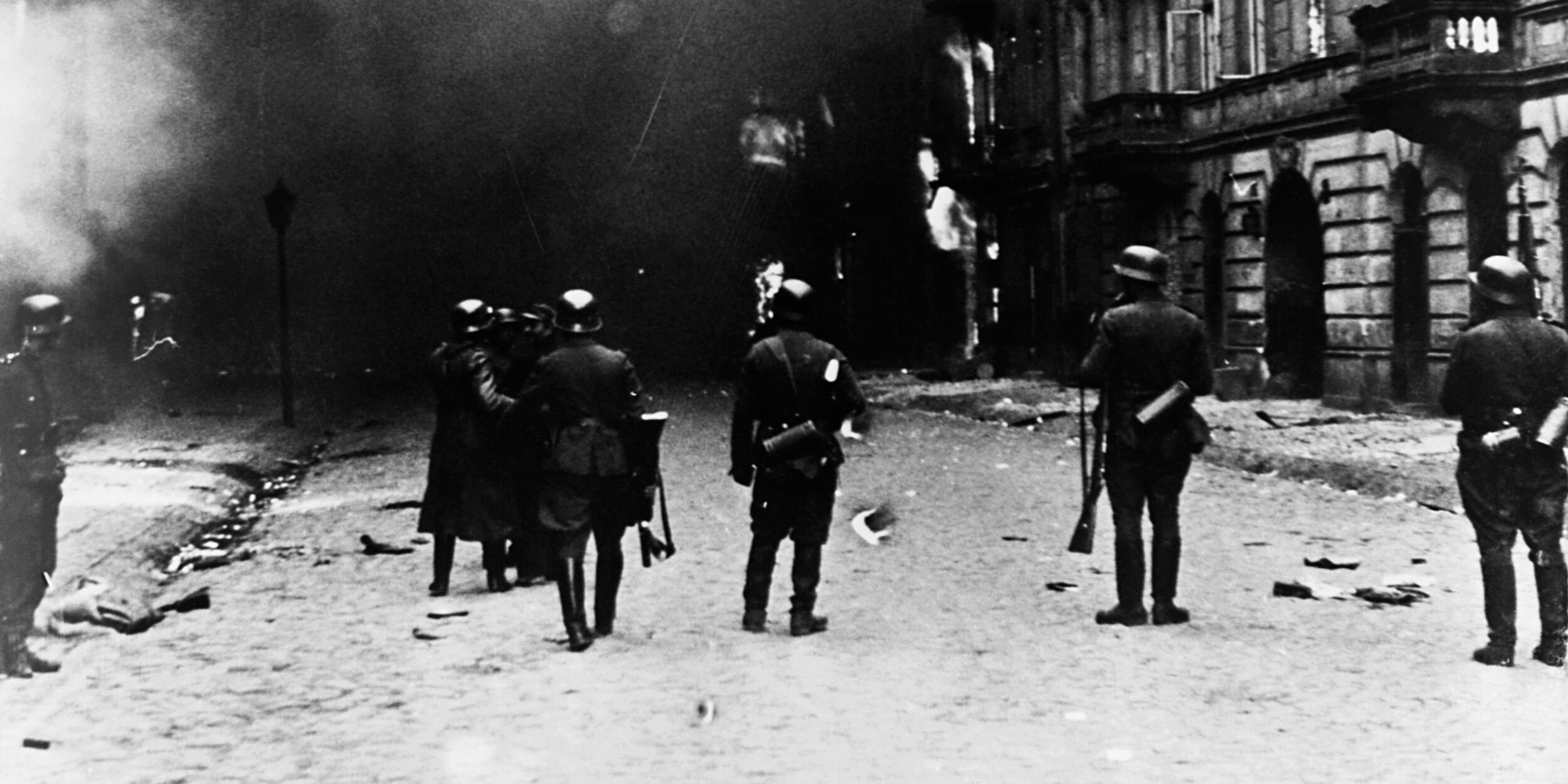

Swirls of black smoke billowed high above the steeples and splintered roofs as Lieutenant Ronald Speirs surveyed the stucco exteriors of storefronts and dwellings pocked by the scars of urban battle. Carentan, the once ornate French commune nestled along the banks of the Douve River, was a charred and blistered shell—a ghostly visage of its former self.

Local citizens had long awaited the hour of liberation from Nazi tyranny. Deliverance thundered forth from a devastating barrage of heavy naval guns, American artillery, and mortars raining ruin upon their historic community. Such was the terrible price of evicting the despised German occupiers.

“The place was a mess,” observed one witness to the carnage. “Buildings on fire, dead Germans lying around, smashed equipment, streets blocked by rubble or with gaping shell holes, and the not-too-distant crackle of small arms.”

Speirs, a Dog Company platoon leader, meandered through the coils of Normandy brush, maintaining a watchful eye on the frontline. His bulky Thompson submachine gun was casually slung over his shoulder.

A displaced victim of a petty officer rivalry, the lieutenant was a relative newcomer to Dog Company. Recent battlefield forays rapidly established the 24-year-old Bostonian’s reputation as a man not to be trifled with. Conjecture regarding his actions against prisoners of war and one of his own belligerent sergeants swiftly became fodder for foxhole scuttlebutt.

The officer’s steely squint, reserve, and boundless stoicism only enhanced his mysterious aura. Despite the intrigue around his thickly concealed persona, the platoon leader faced few challenges in gaining the absolute trust of enlisted men. His unfazed heroics repeatedly inspired those comrades otherwise gripped by fear or self-doubt. Speirs knew how to run an outfit.

This story begins on the night of June 10, while the moon ascended into a clear sky, illuminating the pastoral terrain above Carentan with the power of a searchlight. A great silence hung over the Normandy marshes, like a calm before a storm.

Before daylight on June 11, Speirs awoke to the mellow soundscape of the Douve River, flowing near the regimental bivouac. Lethargy endured despite several hours of sleep. “During the long night airplane flight into Normandy and the six days fighting which followed,” Speirs recalled, “the platoon had only one full night of sleep, and the men were physically and mentally affected. Our food consisted of K rations with which we had jumped, and a resupply of the same after contact with the beachhead was made.”

It was Sunday. Regimental chaplain John Maloney held service and administered the Eucharist to troopers who prayed for continued survival. Food and toiletries were welcome amenities in the ramshackle encampment. News bulletins were scrutinized. Correspondents seeking additional juicy tales roamed the platoons. Fierce-looking operatives of the French Underground, armed with confiscated Mausers, turned up at company command posts with the latest intelligence.

Nearby, liberated vehicles and horses were processed with equal precision. Some of the troopers joked of becoming “airborne cavalry” due to the large number of captured steeds corralled by the division. “Today you could see paratroopers riding nags of all sizes and descriptions,” recorded correspondent William Stoneman.

Even further beyond camp, Graves Registration conducted its somber accounting of soldiers who would fight no more. Clerks combed through the personal belongings of the dead and tended to corpses shrouded in plain cloth bags. Many more of these bags would be filled by week’s end.

In camp, some airborne men already exhibited early signs of psychological distress. Sleepless nights or occasional tremors often forecasted long-standing inner struggles. “Some were able to take the pressure better than others,” recalled Art “Jumbo” DiMarzio, a 19- year-old member of Speirs’s platoon. “Every day was a big problem.”

The clash at Carentan would be no exception.

Perched northwest of Carentan on June 11, Speirs lifted his field glasses and gazed upon the smoldering town below. In those rubble-strewn streets, citizens formed bucket brigades and frantically pumped water into the hoses of overwhelmed and ill-equipped firemen. All the while, Germans covertly bolstered their defenses in anticipation of renewed American assaults.

These enemy troops were members of the feared-but-respected Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6 and 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division. As veterans of Italy and the brutal incursion into the Soviet Union, the tested ranks of the Fallschirmjäger comprised a force not to be underestimated.

In a series of interviews with airborne scholar Mark Bando, Art DiMarzio later acknowledged the aggressiveness of this foe, explaining, “German paratroopers and the SS troopers were good soldiers. Later on during the war whenever the 101st Airborne would appear someplace, the average German infantryman was definitely afraid of us. They were not capable of doing battle with us. So, the German airborne would come to try and hold us back.” The Battle of Carentan proved a microcosm of this pattern.

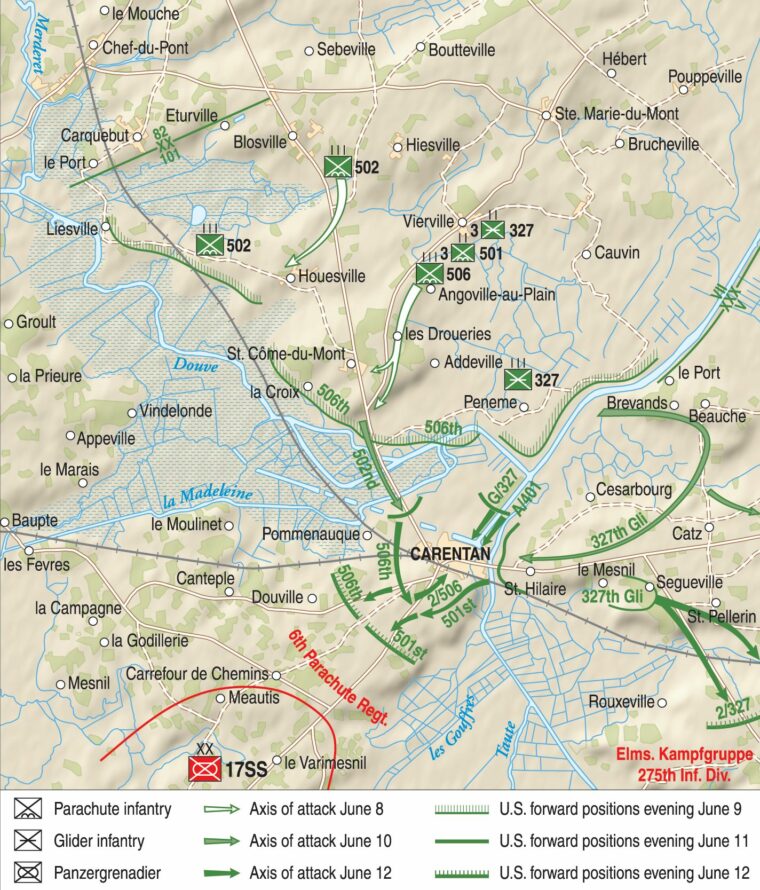

The plan of attack “was to effect a solid junction of the Omaha and Utah beachheads by capturing the city of Carentan. These orders had come directly from General Eisenhower,” Speirs reported. “The mission was given to the 101st Airborne Division. At the same time, V Corps was to attack from Isigny toward Carentan.”

Over the course of the previous day, battalions from the 502nd Regiment plowed towards town but were stymied by murderous fire and obstacles. A mixture of marshes, railroad embankments, narrow causeways, and cunningly deployed enemy emplacements made for a galling task.

“Neither battalion was able to advance,” noted Speirs of preceding attackers, “taking very heavy casualties because of the strong enemy resistance and good defensive positions. The flooded fields to either flank made it impossible to flank the defenders.”

The 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment was therefore tasked with circling around the western edge of the city and pushing toward high ground on the southern outskirts designated as Hill 30. The worrisome enterprise, particularly the nearly unnavigable terrain, left an uneasy feeling in Speirs’s stomach. He held no illusion as to the surprises Germans had in store.

Later assessing his thoughts in third-person, Speirs noted, “The platoon leader and his men were well aware of the German paratroopers’ fighting capabilities because the Germans had defended Saint-Côme-du-Mont and Vierville in the earlier fighting to the north. They attacked strongly when ordered, and were armed with a high percentage of automatic weapons.”

Fallschirmjäger troops sported distinctive camouflage jackets and oblong helmets, making them visually unique in contrast to standard German infantrymen. “Their morale seemed good,” Speirs added. “This was possibly because fighting the Americans was preferable to fighting both Russians and cold weather.”

The hearty spirit of his enemy offered Speirs no consolation. He was further distressed by the presence of German armor in the Carentan sector. Only days prior, outside Saint-Côme-du-Mont, his platoon had encountered an armored car while safeguarding a bridge. The vehicle fired a burst of rounds—killing a GI—before withdrawing to Carentan.

Colonel Robert Sink, commanding officer of the 506th PIR, assembled his officers for a briefing at 10 p.m. Carentan’s deluged environment was a prominent topic of discussion. Paved roads led into the city of 4,000 residents but the surrounding landscape remained problematic.

“The entire area,” Speirs reported, “with the exception of the city, and to the southwest, was swampy and intersected with drainage ditches, streams, and canals. Nowhere does the terrain rise above 30 meters.”

On more open swaths of land, an array of cabbage patches and orchards offered intermittent concealment but hardly enough cover to halt a bullet. Furthermore, Speirs’s platoon carried only one light machine gun since Speirs felt “that riflemen were more valuable during the constant attacking in which we had been engaged. Our light machine guns during the Normandy Campaign were not provided with the bipod, but only a tripod, which was not satisfactory while attacking in hedgerow country.”

Manpower, or the lack thereof, was also a chief concern. Since D-Day, Speirs had lost over half his outfit. Following the briefing, Lieutenant Joseph McMillan— replacement of the deceased Captain Jerre Gross—pulled Speirs aside. “What’s the strength of 2nd Platoon?” McMillan inquired. “Fourteen, sir. Watkins caught some bits of mortar.”

“Consider yourself lucky. Sergeants are running some of the platoons now.”

“I know it.”

“You watch yourself out there.”

“Yes, sir,” Speirs saluted with a reserved grin. Frankly, he was surprised to have survived this long. “Each parachute infantry platoon was authorized two officers due to the expected casualty rate,” he reflected.

The wounding of his assistant platoon leader, Harold Watkins, demonstrated the foresight of such preparation. Watkins recovered from his wounds only to be killed in action in Holland that September.

Second Battalion moved out; Dog Company brought up the rear of the column. “Previously,” Speirs noted, “each company had been given a horse and cart to carry equipment and ammunition. Being airborne, we had no organic transportation. These carts were kept to the rear of the column to eliminate noise.”

Without the assistance of pack animals, the pace of Headquarters Company soon slackened due to its hefty jumble of machine guns, mortars, and rocket launchers. Cautiously advancing in single file, the paratroopers crossed the four bridges spanning the various waterways outside town. “Up ahead,” Speirs continued, “fires could be seen in Carentan, and the booming of the naval gunfire could be heard. The city was given a heavy shelling by the U.S. Navy and other friendly weapons as we moved in.”

The blaze emitted a sinister orange glow in the night sky and cast bright reflections on the peaty fields. The spectacle presented a hellish montage that only further aggravated high anxieties. “The necessity for maintaining silence and keeping contact with the man ahead in the murk left no time for flank security,” Speirs insisted. The men lurked in semi-blindness.

The column exited the roadway upon encountering a desolate farmhouse previously engulfed by combat between German defenders and the 502nd Regiment. The terrain before them grew steeper, further slowing the progress of the encumbered Headquarters Company, and thus the whole formation.

Speirs and his team slung their weapons over their shoulders to help heave the heavy weaponry up the slopes. Fences and shredded debris from prior engagements littered the muddied yards and groves.

“At one gate,” Speirs recalled, “there was a dead paratrooper, and every man in the long column stepped on him in the dark.” The enemy remained silent as the battalion continued its winding probe through the vegetation. A hiss emanating from the fires of Carentan lent an air of boiling tension to the uneasiness.

Subsequent hours witnessed an unintentional game of hide-and-seek as companies lost and regained contact with units to their fronts and rears. Sporadic enemy fire was heard ahead but the trek persevered with sluggish, “uncertain progress,” said Speirs. “The slow movement caused the tired men to doze off to sleep when the column stopped, and the officers in the companies had to wake men up and urge them forward.”

Approximately three hours after the unit set out on its nighttime venture, 1st Battalion at last reached its objective: Hill 30. The Germans had largely left the Americans free to roam into position. Slightly to the west, Speirs deployed his men on both sides of the road to Baupte, where they maintained a watchful eye on the countryside—if they could remain awake.

Fatigue was all too apparent when troopers of Fox Company accidentally shot a 1st Battalion man who stumbled into their lines. Such tragic missteps were more common than soldiers cared to admit.

Company commanders conversed with Colonel Strayer at 2:30 a.m. to choreograph the next day’s action. With heads hunkered under Captain Hester’s rubber raincoat to conceal the flashlight beam, officers leaned in for instructions. From its new overlook, 2nd Battalion was slated to assault Carentan head on.

“The plan was to drive into town and join glider troops attacking from the other side,” Speirs recalled. The companies were to move as one and dislodge German occupiers from the fortified streets, block by block if necessary. The movement was scheduled to step off at 6 a.m.

Shortly after dawn broke around 4 a.m. on June 12, battalion leadership was aghast to discover that, in the confusion of darkness, the regimental command post had established itself well ahead of its own companies. Concealed German gunners quickly capitalized on the error and fired at the misplaced headquarters. A company was promptly dispatched to rescue the besieged command post. From that point, the broader attack unfolded with daring swiftness.

“The desirability of getting into town quickly caused the 2nd Battalion to move straight down the main road in a column of companies,” said Speirs. This tactical decision may otherwise have been considered illogical were it not for the essence of time and the limitations of terrain.

In any case, Fox Company led the way, with Easy and Dog Companies following. Easy Company—Speirs’s future command—suffered considerable casualties when machine gun and mortar fire rained down destruction.

“At Carentan we really had to fight,” wrote Pittsburgh paratrooper Charles Bray to his parents. “After being pinned out by German 88s for a couple of hours, we charged the outskirts of town. About halfway across a field a bullet ripped through the top of my steel helmet, knocking me about two feet in the air. I was dazed, reached up to the top of my head and didn’t see any blood. I knew they missed me, got my helmet, and charged again.”

When Bray neared a house, he was shot clean through the arm. “I couldn’t use it very good then,” he admitted, “so I fired with the other hand for a couple of hours. I was doing all right until I went down again. This time I got it in the side.”

Amid this melee, Easy Company commander Dick Winters was struck in the leg by a ricochet while directing troops at a key intersection. “He was not evacuated,” Speirs assured, “and in spite of a stiff and painful leg, stayed until the end of the campaign.”

Officers recognized the power of maintaining one’s poise under pressure. With much of Carentan cleared of enemy resistance, 2nd Battalion subsequently endured harassing fire from a cluster of houses on the town’s periphery. Troopers rushed to a neighboring home and lobbed a rifle grenade from an upper story, obliterating an enemy machine-gun position.

While the Germans commenced a harried withdrawal, a .30-caliber placed on the same floor violently mowed down scores of the scampering enemy. By 8:30 that morning, the brawl had largely subsided. “D Company was ordered to move into the city and did so,” Speirs concluded of the attack.

The level of carnage inflicted on Carentan was astounding, unlike anything Speirs had yet seen in Normandy. The city “had suffered heavily from the pre-attack shelling; whole blocks were ablaze, while many buildings were in ruins,” he observed. Sadly, the hard hand of war had yet to fully pass over the centuries-old commune. Demanding chores remained for the 101st Airborne Division. Within hours of Carentan’s capture, division headquarters ordered the 506th Regiment to advance to the southwest and seize Baupte.

“When Lieutenant McMillan returned from a battalion meeting with this order,” Speirs recorded, “he was heard with amazement by the platoon leaders. He agreed that the plan, to say the least, was an ambitious one. Four phase lines had been designated” as benchmarks for the attack. McMillan’s platoon leaders— Speirs and two sergeants—“felt the company would be fortunate to reach the first” of those points.

“But the attack was necessary,” Speirs determined. “Otherwise, a German counterattack could pin the division in the city with the enemy in control of the high ground to the southwest.” The men clenched their teeth and prepared for the next round.

The afternoon sun bore heavily on the troopers while they roved in serpentine fashion. As the humidity further dampened their acrid uniforms, members of 2nd Platoon were tasked with clearing the Pommenauque area, a lightly populated suburb on the western fringe of Carentan.

While Lieutenant McMillan progressed with 3rd Platoon on the left, he encountered a lone Frenchman approaching from the general direction of the enemy. Addressing the civilian in broken French, Sergeant Allen Westphal inquired as to the whereabouts and strength of the Germans. The plainly clad resident pointed up the nearby railroad tracks, estimating there were perhaps a thousand combatants hidden beyond view.

McMillan’s shoulders slumped. “This was unhappy news to battered D Company,” Speirs confessed, “but the company pressed on.”

Given this unwelcome revelation, the platoon was relieved to discover only a handful of startled civilians in a smattering of weather-beaten structures. In one of these dwellings, Speirs found a gnarled Frenchman bloodied by the recent American bombardments. Without hesitation, the lieutenant urged the man to seek medical treatment at one of the aid stations in the city Such a pitiful sight underscored the bittersweet consequences of liberation. One United Press correspondent observed, “The French have come through much suffering. They have seen friends and loved ones killed, and they know that often our shells and bombs have done it, but they say: ‘This is the price we pay for liberation.’”

The reporter later encountered a priest uttering burial rites over the remains of innocent victims. The clergyman slowly turned to the Americans and reverently declared, “We thank you for having delivered us.”

pushed west toward Pommenauge and Baupte. OPPOSITE: Smoke rises as paratroopers, ambulances, and a

captured Kubelwagen populate a deserted street in Carentan in this colorized photo taken during the battle

Despite their initial feelings of suspicion and antipathy toward civilians, paratroopers endeared themselves to many townsfolk upon recognizing their appreciation and sacrifice.

“As the platoon moved out of the village to rejoin the company,” Speirs continued, “it was brought under fire by long-range machine guns from the west. By infiltrating the men in rushes across the open fields, the platoon reached the shelter of the railroad embankment with no casualties.”

Third Platoon, located some 500 yards down the cut, was not as fortunate. German machine gunners entrenched themselves in the tracks between railroad ties. From this shrewdly constructed position, they struck down the platoon’s lead scout. Straddling the rails, Speirs’s men scurried to the scene but were of little assistance in alleviating the bottleneck.

With bullets whizzing by, McMillan grasped his walkie talkie and barked into the headset for artillery support. Fellow companies confronted similar obstruction. “German rifle and machine gun fire was intense all along the line and the battalion was unable to advance in any part of the zone,” insisted Speirs. When American artillery and mortars screamed overhead, Dog Company stayed put to avert friendly fire.

At dusk, McMillan received word on his SCR-300 radio to peel back toward battalion headquarters and reconsolidate under cover of darkness. The company’s evening displacement left it bookended by Easy and Fox Companies. “The boundary between companies was a deeply dug dirt road running back to the battalion command post,” Speirs explained. “This area had very thick hedgerows with ditches on both sides and visibility was limited to the small fields between hedgerows.” Potential confusion aside, McMillan safely shepherded his flock to the main line.

The officer generously permitted the bulk of his company a night’s rest while a nearby skeleton crew pulled security at a junction of hedgerows. Those troopers who were granted a reprieve blissfully snored away their previous week of constant bustle. While the ranks savored some rest, McMillan and Speirs made use of this relative calm to conduct a reconnaissance of the company sector. The two officers, craving a few hours of sleep themselves, casually inspected the right flank of their position as evening haze thickened. Out of the corner of his eye, Speirs spotted a squad dart through an orchard opposite his location. Who were these men?

“Night was creeping in and at first I thought it was a friendly patrol, and waved at them from 100 yards distance,” he recalled. “The last two soldiers stopped and looked toward me, and I realized they were Germans passing our flank and headed for the battalion reserve line.”

In a flash, McMillan raced to the command post to sound the alarm. Nervously stumbling through 600 yards of brush and pasture, the lieutenant ran toward the stone house occupied by Colonel Robert Strayer’s headquarters, praying he would reach the structure before the Germans struck.

McMillan’s heart sank when a sudden barrage of small arms erupted nearby. He was too late. The lieutenant arrived just as the Germans contacted battalion sentinels. Fortuitously, troopers of the strained Easy Company were at hand to help quell the sudden incursion.

McMillan’s heroic sprint was not all for naught. While he regained his breath, six American light tanks rumbled into the command post area. Contrary to the wishes of Strayer and Sink, the leader of the armored pack refused to venture closer to the front for fear of becoming lost.

McMillan diplomatically approached the lead tanker, insisting, “You could do some good out there.” The commander accepted the challenge, welcoming McMillan to guide his tank into place. The lieutenant appropriated the seat of the bow gunner and pointed the crew in the proper direction.

Dog Company enthusiastically welcomed this support at its forward position.

Gratification was most notably expressed when the crew sprayed the tree line from which the German patrol had sprung only moments prior. On the company’s front, the enemy remained silent for the duration of the night. The Germans temporarily delayed any aggression. The following day would reveal why.

On June 13, Speirs was entrusted with clearing a farmstead on the right flank, perhaps 400 feet below the city’s southern rail line. “Just before dawn,” he wrote, “the 81mm mortar platoon commenced firing at the house which the platoon was to attack. They fired a heavy concentration, causing the roof of the house to be set ablaze.” The men anxiously neared the property, advancing down the gentle slope to the dwelling encased by a stone wall. At this most inopportune time, the enemy counterattacked.

“We started out towards the farmhouse,” Art DiMarzio remembered, “and when we got to the farmhouse, the Germans opened fire on us.” All hell let loose. What became known as the Battle of Bloody Gulch had begun.

“At that moment,” Speirs added, “a heavy mortar and artillery concentration landed in the area. One of the platoon riflemen was struck by this fire and lay moaning on the ground.”

Unable to withstand this withering barrage, 2nd Platoon leapt into the large courtyard of the fiery farmhouse. The ferocity of German salvos intensified, and the precarious nature of the situation became evident to Speirs. “As I crossed the waist-high wall, I looked back up the hill and saw German soldiers running along the hedgerow we had just left.”

A Browning automatic rifleman pivoted his weapon toward his former lines and peppered the trees. Enemy attackers let forth a stream of agonized cries and whimpers while 2nd Platoon ejected small mountains of brass. DiMarzio pulled the trigger of his M-1 with such hustle that the rifle overheated; the private could barely hold onto his weapon without blistering his hands. Sizzling grease oozed from the rifle’s crevices. DiMarzio was soon on the prowl for additional ammo clips.

The stone wall afforded protection for only so long. In short order, “a shower of grenades was received from the west where the hedgerow blocked our observation,” Speirs remembered. Time seemed to stand still as a downpour of Eierhandgranate 39 fragmentation grenades landed inside the enclosure.

The blows rattled the confined space and spewed shards of hot metal. Fragments of these “small egg grenades” flew into Speirs’s right temple and knee. The punch of the blast jerked him backward upon the ground. He felt as if he had fallen into a swarm of angry hornets; a stinging aggravation was followed by swollen pain. His ears hummed with a hollow ring, dulling the chorus of bangs and booms.

Another grenade bounced off the chest of Private John Dielsi and exploded when it tumbled to the ground, leaving the enlisted man in a convulsing, bloody shambles. The blow left him “kicking and screaming on the stones of the courtyard.” There was no opportunity to tend to the wounds. Germans “began firing from the hill at the machine gunner as he lay exposed behind the gate. The platoon machine gunner was killed, and the machine gun rendered useless.”

Dreaded Fallschirmjäger troops then charged from a woodlot on the platoon’s front.

“They were about 25 yards away and firing as they came,” Speirs reported. “The platoon from behind the wall cut them down with aimed rifle fire and killed them all before any reached the wall.”

The costly success of maintaining the position inflicted a heavy toll on 2nd Platoon. Furthermore, supplies could not be easily replenished. The small outfit was on the verge of obliteration.

The onslaught intensified. Dog and Fox Companies fell back, leaving Speirs’s platoon forsaken in the cloudy confines of the enclosed farmhouse. The enemy counterattack had “stopped the American regiment in its tracks,” acknowledged the lieutenant. “The German intention was to recapture Carentan.”

Despite his hazardous placement and physical injury, Speirs had no intention of being a passive observer to the enemy’s inroads. Now was the time to vacate. “There was no protection against grenades in the courtyard and the burning house was throwing out a suffocating heat and smoke,” he explained. Speirs then noticed a ditch jutting out from the northeast corner of the yard that roughly trailed back to the battalion line. The watery conduit was perhaps the only means of escape. “Second Platoon, on me!” the hobbled lieutenant bellowed. A mad dash commenced.

Amid the speedy withdrawal, one of the enlisted men attempted to retrieve the mangled Private Dielsi for evacuation. DiMarzio interceded. “I told him to leave him there because there was nothing we could do with him anymore. He was flipping around and groaning and was out of control. So we went back to our lines.”

The rushed decision to abandon Dielsi was one the men would deeply regret.

Sloshing up the gulley toward their lines, the troopers traversed the 400 yards, all but collapsing into foxholes upon arrival. Speirs was dismayed to discover that the overall situation had hardly improved.

“F Company had fallen back again to the high ground 100 yards in their rear. This was done without authority from the battalion commander. It was a serious move, exposing, as it did, the entire left flank,” Speirs recalled.

The lieutenant felt this action was a consequential violation of common-sense tactics. In retrospect, Speirs did not consider the column of armor barreling toward Fox Company. That incoming tide greatly influenced the decision to peel back. In any case, “D Company was now filling in the gap between E and F,” he said.

By this point, some of the rattled paratroopers were understandably hesitant to leave the security of their entrenchments.

Speirs denoted their emotional state as “frightened, but not panic-stricken.” Recognizing that consistent gunfire had to be maintained against the adjacent enemy-occupied hedgerows, Speirs kicked the GIs out of their cautious complaisance and threw them back into the engagement.

Lieutenant Thomas Peacock aided in this call to arms by funneling jeeploads of ammunition to the front via the sunken roads. Further back, paint burned off the scorched barrels of the 81mm mortars of battalion mortar platoon leader Frederick “Moose” Heyliger. His men lobbed over 1,000 rounds toward the enemy.

“Unknown to the battalion,” Speirs continued, “help was on the way. Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division had been rushed to the area east of Carentan to meet an expected enemy thrust which did not materialize.”

At 2 p.m. deliverance was announced with the rumbling of 60 Sherman tanks, M5 light tanks, and self-propelled howitzers. “This was a beautiful sight to the battered 2nd Battalion,” declared Speirs. “The tanks were firing as they advanced and doing a wonderful job.” With the assistance of these fresh reinforcements, the Germans were pushed back beyond Auvers. The vital link connecting the American beachheads thus remained unbroken.

Speirs’s platoon relocated to the ruined streets of Carentan and was gratefully placed in reserve. Only 50 fatigued men of Dog Company remained standing. “The amazing thing was that there were not more cases of combat exhaustion,” the lieutenant marveled. “The majority of the men fought bravely, even though the companies were forced to yield ground. The battalion had done its part in defending Carentan, and the men and officers were proud of their job.”

Nazi broadcasters apparently did not receive the word. “Berlin radio boasted that evening to all of Europe that the attack was successful and Carentan was again in German hands,” Speirs recollected with amusement. That same evening, the platoon learned of the terror that befell John Dielsi. Deserted at the burning farmstead by his overwhelmed comrades, the wounded private was left to the mercy of the Fallschirmjäger. The German paratroopers had none to spare.

Having spotted the GI quivering on the ground, one of the enemy plunged his bayonet into the helpless Dielsi. The young American was left for dead. Amazingly, the stabbing failed to extinguish the paratrooper’s life. Once the Germans fled the vicinity, Dielsi inexplicably mustered the strength to crawl in the direction of Carentan, yearning for assistance before he bled out. Medics eventually encountered the half-dead Pennsylvanian and whisked him to an aid station.

Dielsi survived his physical wounds and lived to old age. Sadly, he suffered from emotional trauma the rest of his life. Even in his later years, Dielsi dove under his kitchen table each time he heard a clap of thunder. The menacing sound of the guns never left him. Speirs long felt a sense of guilt for Dielsi’s prolonged anguish. He likewise cast blame on himself for neglecting to submit commendations recognizing his men’s valor on the Normandy battlefront.

Five years later, while enrolled in an Advanced Infantry Officer’s Course at Fort Benning, Speirs reflected on his own shortcomings and successes in a revealing assessment of his platoon at Carentan. The 32-page monograph concluded with these judgments and lessons learned from the operation:

1. Strategic use of airborne is essential. The attrition of trained parachutists in extended ground combat operations as infantry is wasteful and should be avoided.

2. When assigning missions to lower units, the commander must consider the comparative strength of his units as reduced by previous casualties.

3. Bravery in combat must be recognized by decorations and awards. Morale is raised and incentive provided to perform well in future combat.

4. Tables of Organization and Equipment must be constantly revised to increase the fighting strength and capabilities of the unit.

5. Flank security during night movement is essential, regardless of the effect on speed and the physical condition of the men.

6. In night movement, all men must be alert to keep contact both to the front and to the rear.

7. When in contact with the enemy at night, one-half of the unit must be alert and in position to repel attacks.

8. Intelligence agencies must keep commanders informed of the enemy indications. Commanders can then adjust their plans in accordance, avoiding the possibility of surprise by the enemy.

9. Wounded men must be carried along when a unit is forced to withdraw.

10. The hand grenade should be used to full advantage in close combat. The present hand grenade is too heavy for long throws, and, too, it cannot easily be carried in sufficient number for a sustained fight.

11. Soldiers must learn that an enemy assault is repelled by firepower alone. When individual targets cannot be located, continuous area fire must be used.

12. Units are forbidden to withdraw without orders, however desperate the situation. Unit commanders must keep higher headquarters informed of the amount of enemy pressure, and request authority to withdraw prior to movement. Most poignant of Speirs’s observations was his self-condemnation for disregarding Dielsi’s plight. “The platoon leader is to be severely criticized for failing to carry the wounded man back as the platoon withdrew from the house on the thirteenth,” Speirs wrote.

“His assumption that the man was dead does not excuse him. His expectation of another enemy assault and his fear that this would find the platoon with no ammunition were the factors causing this grave mistake.”

Speirs believed that steadfastness to able subordinates was a major underpinning of leadership. The obedience of enlisted men was to be repaid with decisiveness and a sense of stewardship. In the instance of June 13, Speirs believed he had succeeded in the former but failed in the latter.

Moreover, his frank meditation reveals he was not always the cold, heartless warrior some contemporaries thought he was. Speirs preached loyalty to those who earned it. In Dielsi’s unfortunate case, however, the lieutenant had fallen short of his own expectations. He did not accept this transgression lightly.

Naturally, questions of soldierly bearing did not always translate in the harsh realities of the battle zone. The near murder of Dielsi further aggravated his platoon mates. In this ravaged environment, trophy hunting could take a macabre turn.

“The airborne were always looking for something valuable,” explained DiMarzio. Watches and jewelry stripped from enemy dead and prisoners were especially desired. “At one time I had 21 wedding bands on my collar chain,” the private boasted.

One humid day in Normandy, the heat got the best of the Ohioan and a scavenging buddy. “This one dead German was laying on the ground,” DiMarzio continued. When the fellow GI could not salvage a wallet from the blouse of the bloated remains, he grew livid and cut into the German’s uniform with his trench knife.

When the blade punctured the rotting flesh, a noxious gas sprayed into the air. DiMarzio’s chum became further incensed and started kicking the corpse. “You stinkin’ bastard!” he screamed with each blow.

Not to be outdone by a dead man, the paratrooper then unbuttoned his fly and urinated in the open mouth of the deceased German. There was nothing clean or heroic to be found in this style of warfare. After combat, men could descend to a level of savagery previously thought unimaginable.

Such ugliness was cast aside on June 20 when over 1,000 paratroopers of the 101st Airborne, and an equal number of civilians, convened in the town square of Carentan. D-Day already seemed like a months-old memory. Hurling bouquets of flowers, the townsfolk were overjoyed by the presence of their American liberators.

“Vive L’Amerique!” they shouted. Flags flapped from the community’s World War I monument as 11 Americans were bestowed the Silver Star. Standing erect atop a platform bedecked with the Tricolour, General Maxwell Taylor exclaimed “You are here because soldiers of this division are willing to sacrifice their lives. The honor which is given to these men before me not only recognizes their heroic actions but honors every man in the division. We are tonight honoring our living. Later on we will honor our dead.”

Four days later, Speirs was promoted to 1st lieutenant. His coolness under fire, coupled with his unwavering fortitude, more than warranted such recognition.

Reporter William Stoneman marveled at the exploits of such intrepid airborne warriors. “It was a cowboy-and-Indian fight in a strange country,” he described the brutal clashes. Yet, in the correspondent’s mind, one fact was quite evident: “Not every man is a hero in an army but the paratroopers who hit the coast of Normandy came close to reaching that ideal.” Troopers did not mind the accolades.

Speirs was known by many of his men as “Killer.” They claimed he executed prisoners of war on D-Day and even one of his own belligerent sergeants. He was thought by some to be cold and calculative. The young officer frequently earned this reputation.

At the same time, his actions at Carentan demonstrated his ease under pressure and a sincere sense of stewardship over his men. Like many legendary figures of World War II, the lieutenant was an imperfect but daring leader.

Veterans of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment later shared mixed memories of the man’s cruelty and compassion. But in reflecting on their many hardships and close calls, they realized there were few better soldiers to have at their side than Ronald Speirs.

Jared Frederick is a History professor at Penn State Altoona and Erik Dorr is the curator of the Gettysburg Museum of History. They are the co-authors of Hang Tough: The WWII Letters and Artifacts of Major Dick Winters. This article has been adapted from their newest book, Fierce Valor: The True Story of Ronald Speirs and His Band of Brothers, now available in bookstores.

Thank God for those soldiers!