By Joseph E. Lowry

By the early spring of 1865, the Southern Confederacy was on the cusp of extinction. In every theater of the four-year-old Civil War, the gray-clad Rebels were getting the worst of things. In the West, the hard-fighting but poorly led Army of Tennessee had been literally eviscerated by General John Bell Hood’s useless taking of life at the battles of Franklin and Nashville. After the loss of its namesake state, Hood’s army had virtually ceased to exist as a functional military unit.

In the deep South, Maj. Gen. William Sherman’s Union army had cut a relentless swath of destruction 60 miles wide through Georgia, and was now wreaking even more havoc as it marched northward through the Carolinas to unite with General Ulysses S. Grant and the Army of the Potomac somewhere in Virginia. Confederate General Joseph Johnston, commanding the forces opposed to Sherman, admitted in a letter to General Robert E. Lee that he could do no more than “annoy” Sherman’s progress.

In the East, conditions were deteriorating just as rapidly for the Confederates. In January 1865, Fort Fisher, guardian of the port of Wilmington, N.C., fell to a combined Union naval-land assault, effectively closing off the South’s last access to the outside world.

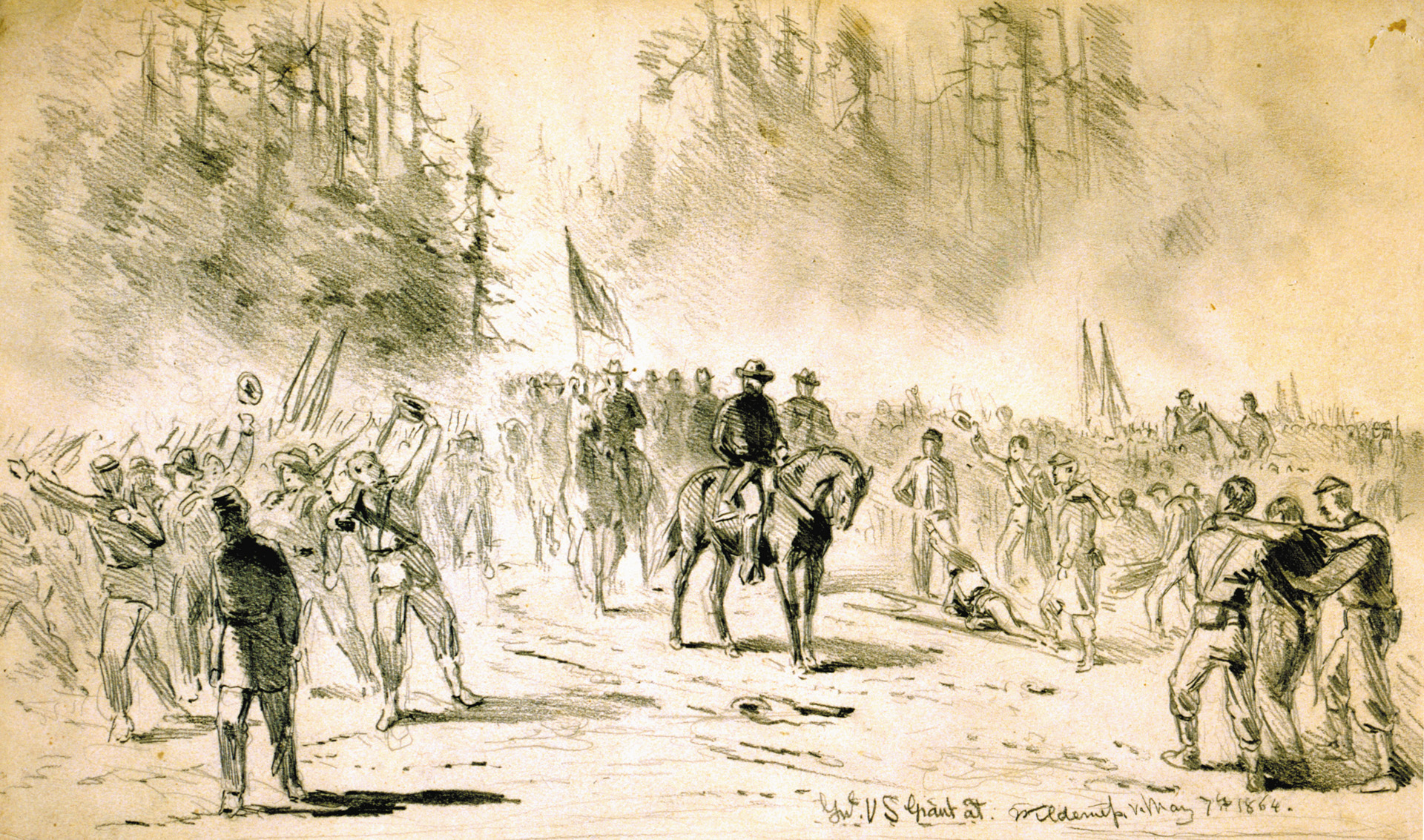

Meanwhile, in the squalid trenches around Petersburg, Va., a key railroad center 20 miles due south of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Grant’s Army of the Potomac continued the embrace of death they had started the previous summer at the Battle of the Wilderness. Grimly and gamely the Confederates clung to their defenses, but hunger, disease, and desertion were taking an ever-increasing toll on the army’s strength, if not its continued willingness to fight. Grant’s Army of the Potomac, better fed and equipped, and increasingly confident of victory, tightened its death grip around the enemy. Each passing day brought renewed pressure as the Federals continued to extend their lines west of Petersburg in an effort to cut off the railroads supplying Lee’s nearly destitute Confederates.

The Confederacy Faces Harsh Realities

The South’s growing desperation and need for manpower led the Confederate Congress in mid-March 1865 to pass a bill that allowed the arming of slaves to fight for the Confederacy. The move, surprisingly, had the grudging support of many Southern officers. One senior officer in Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s II Corps wrote, “I have the honor to report that the officers and men of this corps are decidedly in favor of the voluntary enlistment of the negroes as soldiers.” The measure, however, was much too little and far too late to appreciably improve the Confederacy’s chances for survival.

For Robert E. Lee, the time had come to make a painful decision. While Lee and the men who remained with him were still full of fight, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was equally anxious to continue the struggle, military realities told both men that the end could not be far off unless something drastic was done, and quickly. What course of action offered the most promise of success? For a brief period there was hope that peace with the North might still be negotiated. Francis P. Blair, Sr., a prominent Maryland politician with connections to the Lincoln administration, visited Richmond in January 1865 on his own authority to see if some sort of accommodation could be found that would satisfy both sides. From these discussions evolved an initiative by which a delegation of three Confederate representatives met personally with President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward at Hampton Roads, Va., in February. The Southern delegates, however, were unwilling to accede to Lincoln’s terms for peace—complete military surrender and formal recognition of emancipation for all slaves—and in the end nothing came of the eleventh-hour discussions.

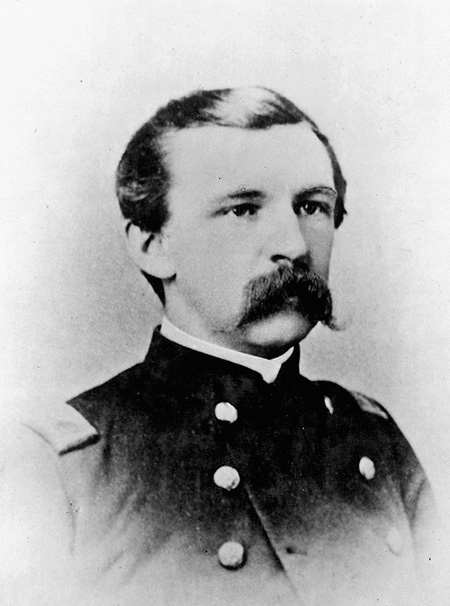

The collapse of the peace talks left Lee with a hellish, unresolved dilemma. What was his duty to the army that was literally falling apart in front of him? In an attempt to resolve this question, Lee turned to his youngest corps commander, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon. With Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Lee’s ever-dependable “Old War Horse,” off covering Richmond’s defenses north of the James River, and Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill, Lee’s other senior commander, increasingly indisposed due to illness, there was nowhere else for Lee to turn. Knowing Gordon to be a superior combat commander, Lee also considered him tough-minded as well as courageous. Leading the defense of the Bloody Lane at Antietam, Gordon had been wounded five times, the final wound a bullet to the face. Only the fact that his cap had a bullet hole in it kept him from drowning in his own blood. Gordon had returned from the Shenandoah Valley in December 1864, and Lee’s confidence in the young general grew even stronger as he came to personally know the 32-year-old Georgian.

“To Stand Still was Death”

On a bone-chilling morning in early March, Lee summoned Gordon to his quarters at the Turnbull House in Petersburg to discuss the deteriorating military situation. Before Gordon arrived, Lee had spread across a table all the various reports he had received from the front. These reports accurately described the parlous condition of the Confederate troops and the overwhelming enemy force arrayed against them. Lee asked Gordon to review all the documents and offer an opinion.

After reading the dispiriting documents, Gordon advised Lee that he saw only three options, which he proceeded to list in the order he felt they should be considered: make the best terms with the enemy that could honorably be obtained; abandon Richmond and Petersburg and, by rapid marches, unite with Johnston’s forces in North Carolina and strike Sherman before he and Grant could combine; or strike Grant immediately at Petersburg.

Lee concurred fully with Gordon’s assessments. Since a negotiated peace was no longer possible and the authorities in Richmond were still reluctant to abandon the capital, the only remaining option was to strike at Grant. “To stand still was death,” Lee reasoned. He directed Gordon to devise a plan by which such a blow could be struck.

A Plan of Fantasy?

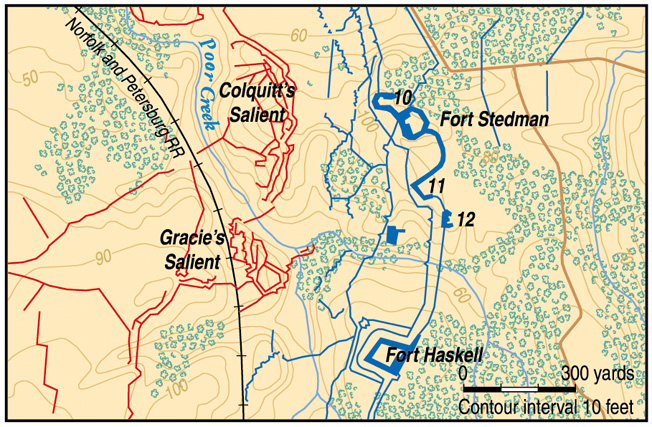

Gordon and his staff spent the next several days studying the Union entrenchments around Petersburg, seeking a weak spot in the Union line. After surveying the enemy works, Gordon decided that the most promising point for a Southern attack was at Fort Stedman (named after Union Colonel Griffin A. Stedman, who had died of wounds received at the Battle of the Crater in July, 1864). It was about 100 yards from the forward Confederate position known as Colquitt’s Salient, and the picket lines were even closer, a mere 50 yards apart. Gordon was bolstered in his opinion that this was the best place for his attack when, during his survey of the Union trenches, he asked one of his subordinate officers if his forces could hold their position against a Union attack. The officer replied that he didn’t think he could hold off such an attack because of the closeness of the lines. Nevertheless, he added, “I can take their front line any morning before breakfast.”

Gordon’s plan of operation, as he proposed it to Lee, was to conduct an attack in the early-morning darkness, with a quick rush across no-man’s-land between the lines. The Union pickets would be quickly and silently overwhelmed, and 50 handpicked men with keen-edged axes would proceed to cut paths through the chevaux-de-frise, wooden obstructions with sharpened stakes laid out by Union engineers. These 50 men would be followed by three companies of 100 men each who would bypass Fort Stedman, leaving it for other supporting troops to capture, and hurry on to the second line of Union trenches. Each man in these companies would wear a white strip of cloth across his breast to identify him as friendly fire in the darkness.

When the select companies made it into the second line, they would identify themselves as Union troops fleeing a Rebel attack, using the name of a Union officer known to be serving in that sector. They would then overpower the Federals and capture three redoubts believed to be located within the works. This would serve to widen the breach in the Union lines and cause consternation among the Union troops. At this point, if all was successful, Confederate cavalry, waiting in reserve, would charge through the gap thus created and make for the Union supply and railroad lines, destroying as many men and supplies as possible.

The chief benefit of attacking in darkness, a tactic not often used during the war, would be the utter surprise of the enemy. In addition to sowing panic in the Union lines, the predawn attack would leave the Yankees confused as to exactly where and how many Confederate troops were actually involved in the assault. It would also prevent Union artillery from firing on the Confederates for fear of killing their own men.

It was hoped that the seizure of Fort Stedman and the works in its rear would convince Grant that his army was in imminent danger of being cut in half and would accordingly force him to constrict his lines. This, in turn, would allow Lee to shorten his own lines and release some of his troops to join Johnston’s army in North Carolina.

From the distant vantage of 139 years, Gordon’s plan seems like the height of fantasy, given the disparate resources and manpower of the opposing sides. At the time, however, it was believed that only an act of true desperation would have any realistic chance of success. Lee, for his part, readily approved the plan, and to carry it off he assigned the three divisions of Gordon’s corps (now reduced to about 8,000 men) and added several brigades from other units, including a division of cavalry, to exploit the hoped-for Confederate breakthrough. All told, Gordon would have at his disposal almost half the remaining strength of Lee’s army. As the ground in the rear of Fort Stedman had undoubtedly changed from its presiege appearance, Gordon requested that Lee furnish him with knowledgeable guides to lead the three assault companies over the ground. Lee agreed. The date for the attack was set for March 25.

“Look Out; We are Coming”

At 4 am on a cold, dark morning, Gordon stood on the Confederate breastworks, a single soldier by his side. The previous night all debris lying in front of the Confederate works was supposed to have been removed so that unobstructed lanes could be used by the assaulting columns. However, as Gordon stood on the breastworks he could see that some debris still remained. He ordered it cleared. The noise made by this work alerted a nearby Union picket, who called out a peremptory challenge: “What are you doing over there, Johnny? Answer quick or I’ll shoot!” Months of living in close proximity had led to an unspoken gentlemen’s agreement whereby pickets would refrain from firing at each other unless it was deemed unavoidable. Gordon hesitated when he heard the challenge, not knowing exactly what to say to allay suspicion. The quick-thinking private at his side met the unforeseen threat by replying: “Never mind, Yank. Lie down and go to sleep. We are just gathering a little corn. You know rations are mighty short over here.” The Union guard answered right away, “All right, Johnny, go ahead and get your corn. I’ll not shoot at you while you are drawing your rations.”

While this exchange was taking place, the last of the debris was cleared from the Confederate front, and the attack was set to commence. Gordon ordered the soldier to fire his musket to signal the assault. A pang of conscience tugged at the veteran—he thought it unfair, even in war, to have lied to a man who would allow him to pick his rations. Gordon, unhampered by such distinctions, repeated the order.

Before firing, however, the soldier called out to his considerate foe, “Hello, Yank! Wake up; we are going to shell the woods. Look out; we are coming.”

With that brief warning, the soldier fired his musket and the offensive began. Rebel pickets, who had crept close to their Union counterparts, overpowered them so quickly that no warning shots could be fired. Some Union reports claimed later that the Confederates had employed the ruse of pretending to be deserters, only to turn on their would-be captors. As soon as the Union pickets were rendered harmless, the 50 axmen leaped over the Rebel breastworks, closely followed by the three 100-man companies, and made haste for the bristling chevaux-de-frise. Clearings were hewn through the wooden obstructions with quick, strong blows from razor-sharp ax heads.

As the three lead companies made their way to the Union rear, the rest of the assault force, following on the heels of the spearhead, rushed Fort Stedman. Fanning out along both sides of the fort, they poured withering fire into the works. Union defenders managed to put up some resistance, firing a few shots of their own at the oncoming Rebels, but the swiftness of the onslaught and the early-morning darkness helped to neutralize any real defense.

The attack was more successful than Gordon could have hoped. Besides Fort Stedman, the Confederates were able to capture three enemy batteries on the north and south sides of the fort. These batteries were unenclosed works housing both cannon and mortars, and quick-thinking cannoneers in the attacking columns turned the guns around and began shelling Federal positions in all directions. In addition to the redoubts and guns, about 500 yards of trench line on both sides of Fort Stedman were taken, as well as some 500 Federal prisoners, including the area commander, Brig. Gen. Napoleon Bonaparte McLauglen.

Battery 9 Holds Firm

Success, however was not complete. Battery 9, north of Fort Stedman, put up stout resistance and halted the Confederate advance in that direction. Similar Confederate assaults against Fort Haskell, south of Battery 12, were also repulsed with much bloodshed. Adding to Gordon’s troubles, word soon came back from one of the commanders of the select companies that he was unable to find the redoubt in the Union rear that he had been assigned to capture as his guide had been lost in the attack. The other two companies reported a similar lack of success.

These unexpected failures jeopardized the entire operation. Without the capture of the additional works and the guns in them, Gordon would not be able to widen the breach and threaten the Union rear. This would also doom any attempts by the Southern cavalry to further exploit the breakthrough and strike Union supply lines.

As Fort Stedman and the adjoining works were being taken, the alarm was sounded in the Union lines. As luck would have it, Maj. Gen. George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, was not immediately available to his men. He was away at City Point conferring with Grant, and the Rebels had cut the telegraph lines between the two points. At this point the Rebels’ luck stopped. Command of the army devolved on Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, a West Point graduate who commanded the IX Corps. Parke, a much-tested veteran of both the eastern and western theaters of the war, kept calm in the face of confused reports from the front. He immediately ordered Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox to organize a counterattack against the Rebels. Parke also called upon Brig. Gen. John F. Hartranft’s 3rd Division, which was in reserve near the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the IX Corps, to reenforce Willcox.

John F. Hartranft: Grizzled Veteran

The Rebels could not have asked for a worse foe than Hartranft. A native Pennsylvanian like Meade and Parke, Hartranft was also a tough, battle-tested veteran. Like Gordon, he had been at Antietam, where he led the 51st Pennsylvania in its famous charge over Burnside Bridge. He also led part of the attack into the Crater the previous July. Hartranft may have been as surprised as anyone at the audacious Confederate attack, but he would not panic and he would not run.

Hartranft’s division was made up of two brigades of six Pennsylvania regiments. He knew he had enough men, about 6,000 in all, to assist in a counterattack, but he may have had some doubts as to how his men would perform. They were all one-year enlistees who had only recently joined the army, and they were still undergoing training when the Confederates attacked Fort Stedman. Green or not, these troops were all Hartranft had to work with, and events would soon test their mettle.

The immediate problem was how best to contain the Confederate attack. While the Union generals may not have known it at the time, this had already been accomplished by the defenders of Battery 9 and Fort Haskell. Not only had they repulsed the initial Confederate assaults, but their cannon fire was deadly and accurate enough to compel the Rebels to confine their forces to the ground already taken.

Years later Hartranft would comment that “great credit is justly due to the garrison of these two points [Battery 9 and Fort Haskell] for their steadiness in holding them in the confusion and nervousness of a night attack … if they had been lost, the enemy would have had sufficient safe ground on which to recover and form their ranks.”

The Yankee Counterattack

With his flanks secured, Parke could concentrate on regaining the ground the army had lost. This was the mission he now gave Willcox.

Troop movements were quickly initiated for a Union counterattack. On the left side of the line, near Fort Haskell, Hartranft placed the 208th Pennsylvania. The 100th Pennsylvania and the 3rd Michigan extended the line to the north. Connecting with these troops toward the Prince George’s Court House Road (the road to the rear of Fort Stedman that Gordon likely would have used to penetrate the rear of the Union lines) were the 207th and 205th Pennsylvania.

On the other side of the line, starting from Battery 9, the 17th and 20th Michigan hooked up with the right of the 209th Pennsylvania. Close to the center of the crescent-shaped line was the 200th Pennsylvania, along with the remnants of the 57th Massachusetts, whose camp had been overrun in the initial Confederate attack. Artillery under the command of Brevet Brig. Gen. John C. Tidball was set up behind the Union lines. In conjunction with the guns from Battery 9 and Fort Haskell, these guns began playing havoc on the Rebel troops.

As the Union infantry moved into line, Hartranft conferred with Willcox. They noticed increased musket fire coming from the Rebel lines, an indication that the enemy was again getting ready to advance. Hartranft, taking personal command of the counterattack, immediately ordered the 200th Pennsylvania and 57th Massachusetts to move against the enemy troops now advancing up the Prince George’s Court House Road. The Federals quickly attacked and plowed through the enemy skirmish line, but soon found themselves facing more Rebels in the entrenched works surrounding Fort Stedman.

Confederate musket fire was severe and, supported by the captured guns of Fort Stedman, took a heavy toll on the Pennsylvanians, causing them to retreat a short distance. Hartranft, concerned that the Rebels would try to take advantage of this withdrawal, quickly rallied the men and attacked a second time, gaining and holding the ground for about 20 minutes before retreating to the Union works. The effect of these attacks was to halt any further Confederate advance and allowed the remaining Union troops to come up in support.

The last regiment of Hartranft’s division, the 211th Pennsylvania, now made its first appearance on the field, having rushed from its camp some miles to the rear. With their arrival, Hartranft’s counterattacking force was complete.

The Confederate Plan Crumbles

It was now about 7:30 am, and the morning sun was rising higher in the cold March sky. The Confederate advantages of surprise and darkness had long since disappeared. Parke ordered Hartranft to attack the Rebels again and recapture the lost ground. Hartranft passed the word to his subordinate commanders that the attack would begin in 15 minutes. The signal would be the advance of the 211th. The Southern troops could probably see what was coming, but now they could do nothing to stop it.

At the appointed time, the 600 men of the 211th Pennsylvania rose as one and charged toward the Rebel line. They were met by Confederate cannon and musket fire, but stoutly pushed on. The other regiments took their cue from their Keystone State comrades, and the whole Union line moved forward.

Just as the full attack began, however, Hartranft received orders to halt and await reinforcements from the VI Corps. Hartranft barely hesitated a second before disobeying the order. He was sure the countermanding order would not reach all the troops in time, and he firmly believed that victory was assured. “I saw the enemy had already commenced to waver,” he remembered, “and that success was certain.”

Hartranft’s battlefield judgment would prove correct. Acting not like the green troops they were but like gray-bearded veterans, the Pennsylvanians fought tenaciously and courageously. Despite the intensity of the combat, they soon drove the Confederates out of the recently captured works.

Hartranft later wrote, “The division charged with a will, in the most gallant manner, and in a moment Stedman, Batteries 11 and 12 and the entire line which had been lost, was recaptured with a large number of prisoners, battle-flags and small-arms.”

Gordon was convinced that continued fighting would be futile. He apprised Lee of the worsening situation, and around 8 am Lee gave Gordon permission to withdraw his troops.

Collapse of the Confederate Ranks

It was an order easier to give than to obey. By the time the withdrawal order reached the front, the increasingly confident Federals were pouring a veritable storm of shot and shell over the entire length of the Confederate retreat. The added fire from the Union infantry reoccupying Fort Stedman only made the retreat more difficult. Gordon himself was slightly wounded as he ran back to the Rebel line.

The effectiveness of the Union artillery shell fire was attested to by a Union medical officer, who wrote: “The great majority of the Rebel wounded fell into our hands, and the wounds were all very severe. An unusually large number of shell wounds of the thigh and legs, demanding amputation, were seen.” Confederate Brig. Gen. James A. Walker personally attested to the deadly dangers of the retreat. “I found myself crossing the stormswept space between us and our works. At first I made progress at a tolerably lively gait, but I wore heavy cavalry boots, the ground was thawing under the warm rays of the sun, and great cakes of mud stuck to my boots; my speed slackened to a slow trot, then into a slow walk, and it seemed as if I were an hour making that seventy-five yards…deadly minie balls were whistling and hurling as thick as hail. Every time I lifted my foot with its heavy weight of mud and boot, I thought my last step was taken. Out of a dozen men who started across that field with me, I saw at least half of them fall, and I do not believe more than one or two got over safely. When I reached our works and clambered over the top, I was so exhausted that I rolled down among the men, and one of them expressed surprise at seeing me by remarking: `Here is General Walker; I thought he was killed.’”

Seeing that death would be their probable fate, many Confederates refused to even try to make it back to their own lines, preferring to surrender where they stood. A large number of skulkers in the Rebel ranks refused to obey their officers on the field, no matter what order or entreaty was made.

One Union major captured earlier when Fort Stedman was overrun commented that “the numbers of stragglers and skulkers was astonishingly large, and I saw several instances where the authority of the officers who urged them on was set at defiance.”

A Losing War

Thus, an attack that had started with such promise ended in abysmal failure. More than 3,500 Confederates were casualties, including some 1,900 who were taken prisoner. Nine stands of colors were also captured. Later that day other Union commanders assaulted the Confederate lines to the southwest. While these attacks were halted short of the main Confederate trenches, a number of fortified picket lines were captured, bringing the Union army that much closer for a final grand assault and costing the Confederates another 2,000 sorely needed men.

Robert E. Lee, who had taken many successful gambles during the war, reluctantly realized that this last throw of the dice had completely failed. As he rode away from the scene of the defeat at Fort Stedman, he knew that the end of the war could not be long in coming. On his way back to the Turnbull House, he encountered his sons Rooney and Rob. Lee, who had always been careful not to outwardly display his emotions, could not hide his manifest disappointment at this latest turn of events. Rob noted all too clearly “the sadness of his face, its careworn expression.”

While brilliant in conception and initial execution, the ultimate failure of the attack on Fort Stedman accomplished nothing except to burnish the already-formidable reputation of Confederate valor and the equally proven stalwartness of their Union foes. It would take two more weeks and much additional bloodshed at Fort Gregg, Sayler’s Creek, and Five Forks for the war in the east finally to end. If Ulysses S. Grant had mounted the breastworks at Fort Stedman that morning and looked over the backs of the retreating Rebels, far off in the distance he might have been able to glimpse the small village of Appomattox Court House and the front parlor of Wilmer McLean’s red brick home.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments