By Mike Phifer

Robert the Bruce, the newly crowned king of Scotland, reined his horse in front of the gates of Perth on the bank of the Tay River in central Scotland on June 18, 1306. Behind the sturdy rock walls of the town were approximately 3,000 troops commanded by Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, who had been dispatched by King Edward I of England to crush the upstart Bruce. With an army of about 4,500 men, Bruce was not strong enough to invest the town. Instead he challenged the Earl of Pembroke to come out and fight or surrender the town.

Pembroke did neither. Claiming it was too late in the day to fight, Pembroke stated he would come out the next morning. Bruce took him at his word and retired his army about six miles away near the village of Methven. Pembroke attacked before dawn the following day, catching Bruce’s men completely by surprise.

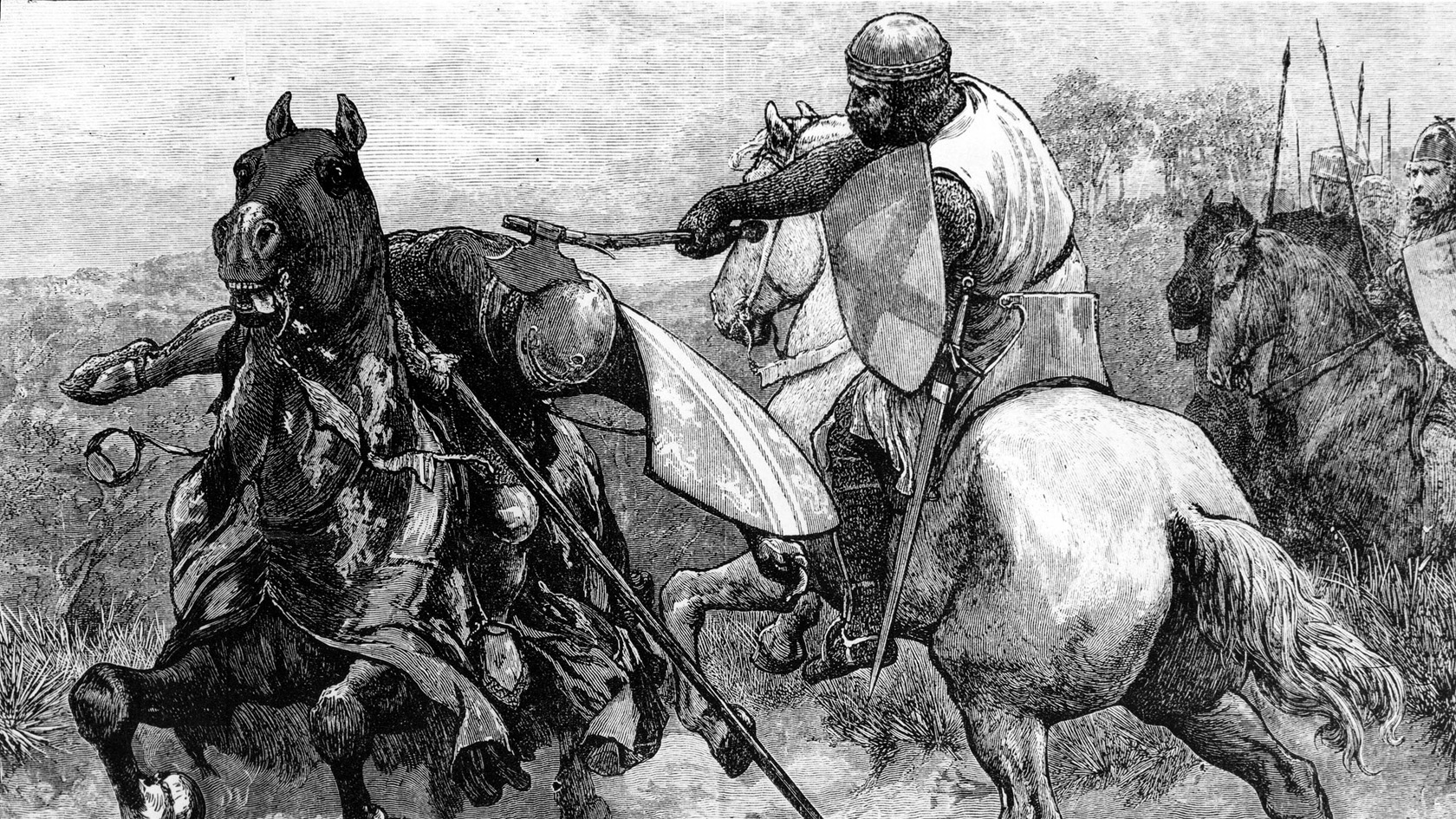

In the swirl of battle Bruce killed Pembroke’s horse but was soon unhorsed himself. As Bruce was mounting another horse, an enemy knight seized the horse’s bridle. “Help, Help,” shouted the enemy knight. “I have the new-made king.” Fortunately for Bruce, one of his men spurred to his aid and knocked the enemy knight to the ground. Bruce regained control of his mount but in the ensuing one-sided battle he would be unhorsed twice more.

With a small knot of knights, Bruce managed to cut his way through the enemy lines and escape. It was a crippling defeat for Bruce, who had lost most of his army. As he and his handful of men escaped into a mountainous region, events were about to take a sharp turn for the worse for the new king.

Robert Bruce was born on July 11, 1274, likely at Turnberry Castle in southwest Scotland. Bruce’s Anglo-Norman lineage on his father’s side held estates in England, as well as considerable holdings in southwest Scotland. Through his Gaelic mother’s side more land came under his father’s control, which earned him the title of earl of Carrick in right of his wife. Growing up Bruce was trained with weapons and horses at which he became quite proficient. Knighted at an early age, Bruce’s martial skills would serve him well as Scotland fell into an era of turmoil in 1286.

That year King Alexander III of Scotland was killed when his horse fell off a cliff. The only heir to the throne was his young granddaughter, Margaret, the Maid of Norway. A council of guardians was established to govern the kingdom while it was decided who would rule Scotland. The council sought the advice of Edward I, Alexander III’s brother-in-law.

Edward, who was known as “Longshanks” because of his towering height, saw a chance to control Scotland, so he agreed to help the Scots. It was decided that his son, Edward of Caernarvon, would marry Margaret when they became of age. But the Scots insisted that despite the marriage Scotland would remain an independent kingdom. As it turned out, there would be no marriage because young Margaret died shortly after arriving in Orkney. This once again raised the thorny question of who should rule the northern kingdom.

Two candidates from rival families, both of whom were descendants of King David I, who had reigned from 1124 to 1153, stood out among the 14 men who claimed the right to the throne. One of the men was Bruce, and the other was John Balliol.

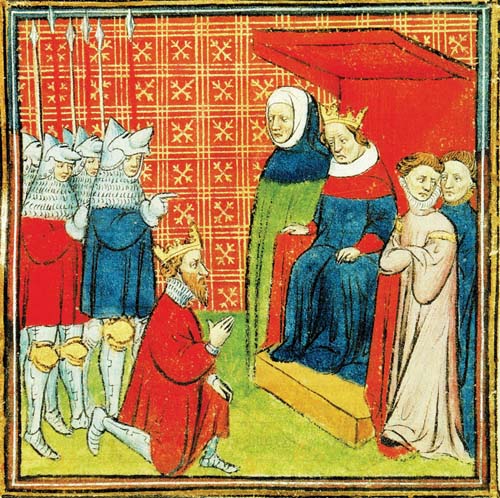

In his capacity as Scotland’s overlord, Edward I chose Balliol in November 1292 to be king. As far as Edward I was concerned, Balliol would be subordinate to him. Balliol soon found himself humiliated by Edward I, who made his authority known not only to the king of Scotland but also to its people. By 1295 the Scottish lords had lost their patience. They urged Balliol to reject his allegiance to Edward and seek a treaty with the French. Balliol’s time on the throne was short as the formidable Longshanks marched into Scotland and defeated the Scots, sending their king to the Tower of London.

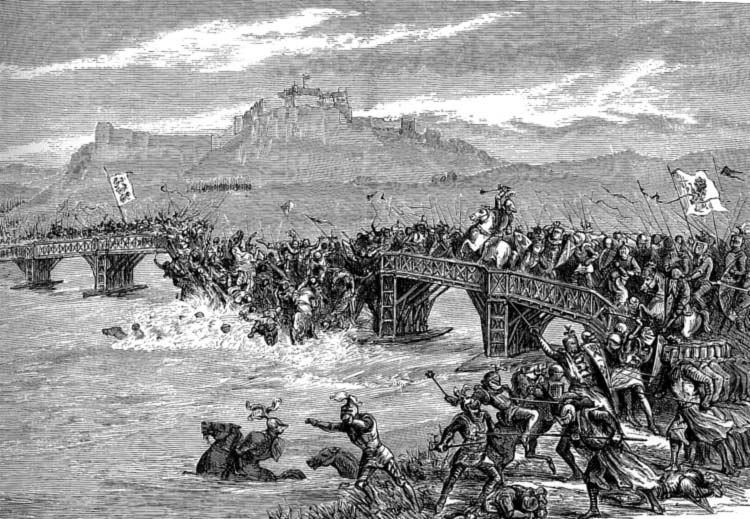

Assuming the sovereignty of Scotland and leaving the Earl of Surrey to govern there, Edward I returned to England in the autumn of 1296. The following year William Wallace led an uprising. He inflicted a decisive defeat on English co-commanders John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, and Hugh de Cressingham at Stirling Bridge on September 11, 1297. A number of Scottish nobles joined the uprising, one of whom was Bruce, despite the disapproval of his father, a supporter of King Edward.

In March 1298 Wallace was proclaimed guardian of the kingdom. He would not last long in this role because Longshanks was determined to bring the Scots to heel. Edward invaded Scotland and defeated Wallace on July 22, 1298, at Falkirk. Wallace, who initially succeeded in evading capture, resigned his title. Bruce, along with his family’s rival John Comyn III of Badenoch (known as the “Red” Comyn), became co-guardians of Scotland. This uneasy alliance soon ruptured. Balliol was released to France under papal custody. This compelled Comyn and his supporters to try again to take the Scottish throne. Refusing to support this, Bruce withdrew to southwestern Scotland to guard his family’s properties.

Meanwhile, Edward continued his war against the Scots. Offered a pardon and generous terms from Edward I and still concerned over a restoration of Balliol, Bruce changed allegiances in 1302. He campaigned with the English in 1303 and 1304. By that time most of the Scots were looking for peace, having realized that neither French aid nor the restoration of Balliol was likely to occur. Longshanks once again controlled Scotland.

By 1306 Bruce ruled his family’s vast estates following the death of his father two years earlier. It was that year that Bruce saw his opportunity to claim the throne as it was rumored that the 65-year-old King Edward was nearing death. The Scots chafed under English rule. Scottish unrest had been stirred by the brutal execution of Wallace in August 1305. Wallace had been captured and transported to London where he was tried for treason and condemned to death. He was then tortured, hanged, and drawn and quartered.

Bruce reached out to his rival “Red” Comyn to discuss the possibility of mutual assistance. The meeting was held on February 10 at Greyfriar’s Church in Dumfries, and things took a turn for the worse.

It is unclear what happened in the meeting. Possibly Comyn threatened to reveal Bruce’s plan to Edward I. As Balliol’s nephew and his closest male relative, Comyn was in line for the throne and was a threat to Bruce’s bid to become king. Whatever the cause, Bruce stabbed Comyn and left him bleeding on the church floor. Bruce went outside and told his two companions what had happened. They quickly went to finish off Comyn.

Bruce then made his way to Glasgow where he met with Bishop Robert Wishart, who absolved him of killing Comyn. The Scottish clergy were mostly supportive of Bruce’s claim on the throne and would aid greatly in the coming war of independence. On March 25 at Scone Bruce was crowned Robert I of Scotland.

Bruce was far from ruling Scotland as the Comyns and their supporters strongly opposed him. Edward I was incensed over Bruce’s actions and began raising a force to crush him. Sending his wife, daughter, and sisters to Kildrummy Castle where his brother Neil would protect them, Bruce pushed on with his growing army to Perth. Pembroke subsequently inflicted a devastating defeat on Bruce at Methven.

Escaping westward, Bruce was pursued and defeated by an enemy detachment. Bruce’s little party escaped but soon found more trouble when they were attacked by the MacDougalls and Comyn’s allies and relatives. Although he lost some horses, Bruce was able to safely extract his force. He then sent some horses to Kildrummy Castle to aid his family in their planned escape to Norway.

By this time Caernarvon had arrived in Scotland with reinforcements. As far as Caernarvon was concerned, Bruce and his men were outlaws and were to be shown no mercy. Kildrummy Castle fell to Caernarvon in September with many of Bruce’s supporters being hanged. Neil Bruce was hanged and beheaded. The Earl of Ross, a Comyn supporter, transferred the Bruce women to England. Their plans to flee to Norway were dashed.

Bruce and his men made their way to the western coast and traveled by ship to Rathlin Island off the coast of Northern Ireland. Although things looked grim, Bruce looked to renew the fight. With the help of Angus MacDonald of the Isles and his fleet of galleys, Bruce began to recruit men. He sent two of his brothers to Ireland, while Bruce sought support throughout the western highlands of Scotland and its islands.

Bruce returned to his castle at Turnberry on the mainland in early 1307. His first move was to destroy a garrison of 200 English troops billeted in a village not far from the castle. Hiding in the forests, hills, and moors, Bruce waged a guerrilla war against his enemies. Unfortunately, his two brothers, Thomas and Alexander, had met with disaster attempting to come ashore in Ireland. They were captured by the MacDowells of Galloway and transferred to Carlisle, where they were hanged and beheaded.

Bruce continued to attack small enemy parties and then fell back into the hills. Castles that fell into his hands were destroyed to deny them to his enemies. After a minor engagement with Pembroke at Glen Trool in April, Bruce changed tactics and prepared to meet him and his force of 3,000 men in battle. Positioned near Loudon Hill where the road led through marshy terrain, Bruce ordered his 600 men to dig three trenches to further narrow the battlefield. This would not only prevent Bruce’s force from being flanked, but would prevent the enemy from bringing the full force of its numbers to bear. In the clash that unfolded on May 10, 1307, Bruce’s spearmen soundly defeated Pembroke.

Longshanks died on July 7 en route with his army to Scotland to punish Bruce. His son rode north from London to take charge of the expedition. On July 20, Caernarvon was proclaimed Edward II. Bruce purposely avoided battle with Edward II. The new king returned to England to deal with domestic problems. These matters kept him away from Scotland for three years.

With Edward II back in England, Bruce took his vengeance against the MacDowells and their allies. Leaving his trusted lieutenant James Douglas to finish subduing Galloway, Bruce turned his attention toward dealing with the MacDougalls; William Ross, Earl of Ross; and John Comyn, Earl of Buchan. Bruce defeated Comyn at Inverurie in May 23, 1308. While Comyn fled to the safety of England, Bruce and his men ruthlessly devastated Buchan’s lands.

Bruce then marched southwest to deal with John of Argyll, also known as John MacDougall. Learning of Bruce’s advance, Argyll laid an ambush on the mountain side overlooking the narrow Pass of Brander. A savvy guerrilla fighter, Bruce anticipated the trap and dispatched archers under Douglas, who had rejoined the king, to get behind Argyll’s men.

As Bruce marched the rest of his army into the mouth of the pass, Argyll’s men rolled boulders at them. Douglas’s archers fired showers of arrows at Argyll’s men, catching them completely by surprise. Caught between Bruce’s charging men and Douglas’s archers, the Argyll men beat a hasty retreat. They were closely chased by Bruce’s men, who slaughtered many of them. Argyll eventually escaped to England. When Ross surrendered to Bruce on October 31, the campaign against Bruce’s enemies came to an end.

After temporarily patching his internal problems in England, Edward II finally invaded Scotland in 1310. The campaign failed due in part to Bruce’s Fabian strategy. He studiously avoided battle and conducted a scorched earth campaign. In mid-1311 Edward returned to London.

Bruce then carried the war to northern England. His troops ravaged towns and villages in the northern counties of England. To avoid the Scots’ depredations, many communities made ransom payment to Bruce. The Scottish king used this money to finance sieges of English-held castles and fortified towns in lower Scotland.

One such fortified town was Perth, which boasted large stone walls and towers. It was further protected by a moat on three sides and the Tay River on the remaining side. After a failed six-week siege Bruce withdrew at the end of December. For eight days he waited before creeping back to Perth on the night of January 7. Previously Bruce had discovered a spot in the moat that could be waded. Now with the cold water up to his neck and spear in hand to test the depth, Bruce led a company of men across the moat. With ladders they stealthily climbed the stone walls and proceeded over the ramparts. Perth was soon in Bruce’s hands.

More castles fell to Bruce and his lieutenants, including Rushen Castle on the Island of Man. This castle was held by Dungal MacDowell, the man who handed over Bruce’s brothers to the English to be executed. The castle fell to Bruce on June 12, 1313; however, MacDowell apparently escaped to Ireland.

By early 1314 only a couple of key English strongholds remained, one of which was Stirling Castle. Bruce entrusted his brother Edward to take the castle, making an agreement with the Stirling’s castellan, Sir Philip Mowbray, in mid-May that if the castle were not relieved by June 24, it would be surrendered.

As the situation in Scotland continued to worsen for Edward II, an English army composed of 11,000 foot soldiers and 2,250 cavalry assembled at Berwick. With word of the deadline for the surrender of Stirling Castle, Edward II hurried to get his army moving north.

Bruce had 6,000 foot soldiers and 350 cavalry to face Edward. On June 22 he took up position near a stream called Bannockburn a few miles south of Stirling Castle. The next day, as the vanguard of the English neared Bannockburn, a contingent of English knights forded the stream believing the Scots were falling back. They were soon surprised when they spotted Bruce leading a contingent of cavalry.

An English knight, Sir Henry de Bohun, leveled his lance and charged toward Bruce. Accepting the challenge for single combat, Bruce galloped toward him, dodged Bohun’s lance and standing in the stirrups drove his battle axe through the knight’s helmet and into his skull. Bohun slid dead from his horse and the remaining English knights retreated.

Meanwhile, another contingent of English knights attempting to skirt around Bruce’s left flank were eventually driven back in a brutal encounter with Scottish pikemen. Since it was getting late in the day, Edward II’s tired cavalry and some of his exhausted foot soldiers encamped for the night across the Bannockburn. The rest of the foot soldiers camped on the south side of the stream.

That night at a council of war Bruce considered retreating; however, a Scottish knight in Edward’s service deserted and informed Bruce that the English were demoralized. Bruce resolved to fight to the finish.

The next morning the Scots moved forward to attack. English archers opened up on them, but they soon were forced to quit as the Earl of Gloucester quickly formed up his cavalry and charged into the Scots. He was met with a wall of pikes and was slain. The Scots continued to press their assault against the disordered English, who were crammed into a small battlefield with marshes and woods on either side. Due to the narrow front, most of the English foot soldiers were unable to deploy. English archers, however, managed to position themselves on the flank and pour arrows into the Scots.

Bruce ordered his cavalry to scatter the enemy archers. As the English wavered and gave ground, Scottish archers fired into their ranks. The English then spotted what appeared to be fresh Scottish troops arriving on the battlefield. In reality, these were the camp followers and other noncombatants who had taken up various weapons and where charging toward the melee.

With casualties mounting, many of Edward’s lieutenants believed the battle was lost. To protect him from death or capture, Edward was forcibly removed from the battlefield by a small group of knights. They tried to take him to Stirling Castle, but he was refused entry by Mowbray. Mowbray knew that Stirling Castle would have to surrender, and the castellan did not want Edward to fall into Bruce’s hands if he were in the castle at the time. Edward eventually made his way back to England, having suffered a terrible defeat.

Yet, the struggle was far from over because Edward II still refused to recognize Bruce as king of Scotland. In the years that followed, Bruce and his lieutenants continued to take fire and sword to northern England. Berwick fell in 1318 to the Scots. Not all went well for Bruce, though, as the Scottish military adventure in Ireland failed and his brother Edward was killed there in 1318. Edward II mounted his last invasion of Scotland in 1322, which also ended in failure.

In 1327 Edward II was deposed as king and his 14-year-old son, Edward III, took the throne. Through the influence of his mother Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer, which pervaded the government, Scotland’s sovereignty was recognized in 1328 with the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton after it was feared Bruce would occupy parts of northern England. King Robert I did not get to enjoy Scottish independence for very long for he died on June 7, 1329.

Independence would prove fleeting for Scotland. The Second War of Scottish Independence began just three years after the Scottish king’s death.