By Stephen D. Lutz

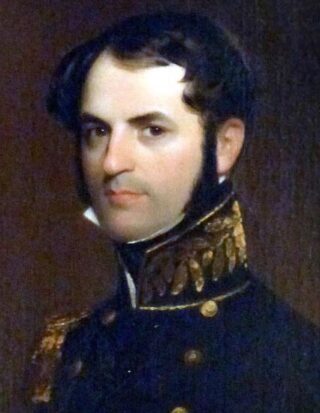

When the Civil War began in April 1861, there was more talk in Richmond, Virginia—certainly among the ladies—about Sydney Smith Lee than about his younger brother. Many, including leading Southern socialite Mary Chesnut, considered Smith, Robert E. Lee’s older brother, to be “the handsomest man in the Confederacy,” and given his illustrious record in the United States Navy prior to the war, great things were expected of him. Indeed, had the war not come about, the elder Lee brother undoubtedly would be the better remembered of the two today.

Smith and Robert Lee’s Early Years

The brothers were raised first in Westmoreland County, Virginia, at the family home, Stratford Hall Plantation, which had been built around 1730 on the west bank of the Potomac River, 10 miles from the nation’s capital. Their father, Revolutionary War legend Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee was a widower when he married their mother, Anne Carter. Unable to return to the family plantation before giving birth to her second son, Mrs. Lee was taken in by family friends named Smith. In return for the neighborly hospitality, the grateful mother gave her son the middle name of “Smith” in their honor, and it was as Smith Lee that he was known to his family and friends.

In all, Mrs. Lee gave birth to five children, three sons and two daughters. Between Smith and Robert, the two boys closest in age, there was always a strong bond, one that they retained throughout their lives. Following the death of their wastrel father, the family moved to Alexandria. Despite having little money, Mrs. Lee was not without connections. As the widow of one of the Revolution’s true heroes, she still commanded respect. In 1820, thanks largely to the family name, Smith entered the U.S. Navy as a midshipman. The appointment came directly from President James Monroe, a fellow Virginian. The Navy at the time lacked a land-based military academy, and Smith began his naval education at sea. It was literally on-the-job training. Few brothers were more different in temperament than Smith and Robert Lee. Smith, five years older, was far more mirthful than the serious, contemplative Robert. When Robert married Mary Custis on June 30, 1831, best man Smith kept the festivities going for a full week following the exchange of marriage vows. And though Smith himself would marry 23-year-old Anne Marie Mason, the niece of U.S. Senator James Murray Mason, in 1834, feminine attention always seemed to follow him about. As late as May 15, 1861, Robert was writing to his wife: “Smith is well and enjoys a ride in the afternoon with Mrs. Stannard. The charming women, you know, always find him out.”

Ordinance of Secession

Smith became a lieutenant on May 17, 1828, during his eighth year in the Navy. From there, his career skyrocketed. After various tours of duty in the Pacific, Mediterranean, and West India fleets, in 1853 he accompanied Commodore Matthew Perry on the epochal voyage to Japan that opened up the country for trade. Smith commanded Perry’s flagship, the USS Mississippi, during the expedition. Meanwhile, Robert had graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and begun a series of assignments as an Army engineer. As much as they were able, the brothers timed their furloughs to coincide, but reunions became increasingly rare as their various military responsibilities increased.

As with much of the nation, the Lee brothers were placed in a moral and ethical quandary by the impending Civil War. Each had served for more than three decades in the nation’s armed forces, but each was also a native son of Virginia. On April 20, 1861, Robert wrote to his brother: “My Dear Brother Smith. The question which was the subject of my earnest consultation with you on the 18th ins. has in my own mind been decided. After the most anxious inquiry as to the correct course for me to pursue, I concluded to resign, and sent in my resignation this morning. I wished to wait till the Ordinance of Secession should be acted on by the people of Virginia, but war seems to have commenced, and I am liable at any time to be ordered on duty which I could not conscientiously perform. To save me from such a position, and to prevent the necessity of resigning under orders, I had to act at once, before I could see you again on the subject as I had wished. I am now a private citizen, and have no intention than to remain at home. Save in defense of my native state, I have no desire ever again to draw my sword. I send you warmest love. Your affectionate brother, R.E. Lee.” Ultimately, both brothers resigned their U.S. commissions and joined the nascent Confederacy.

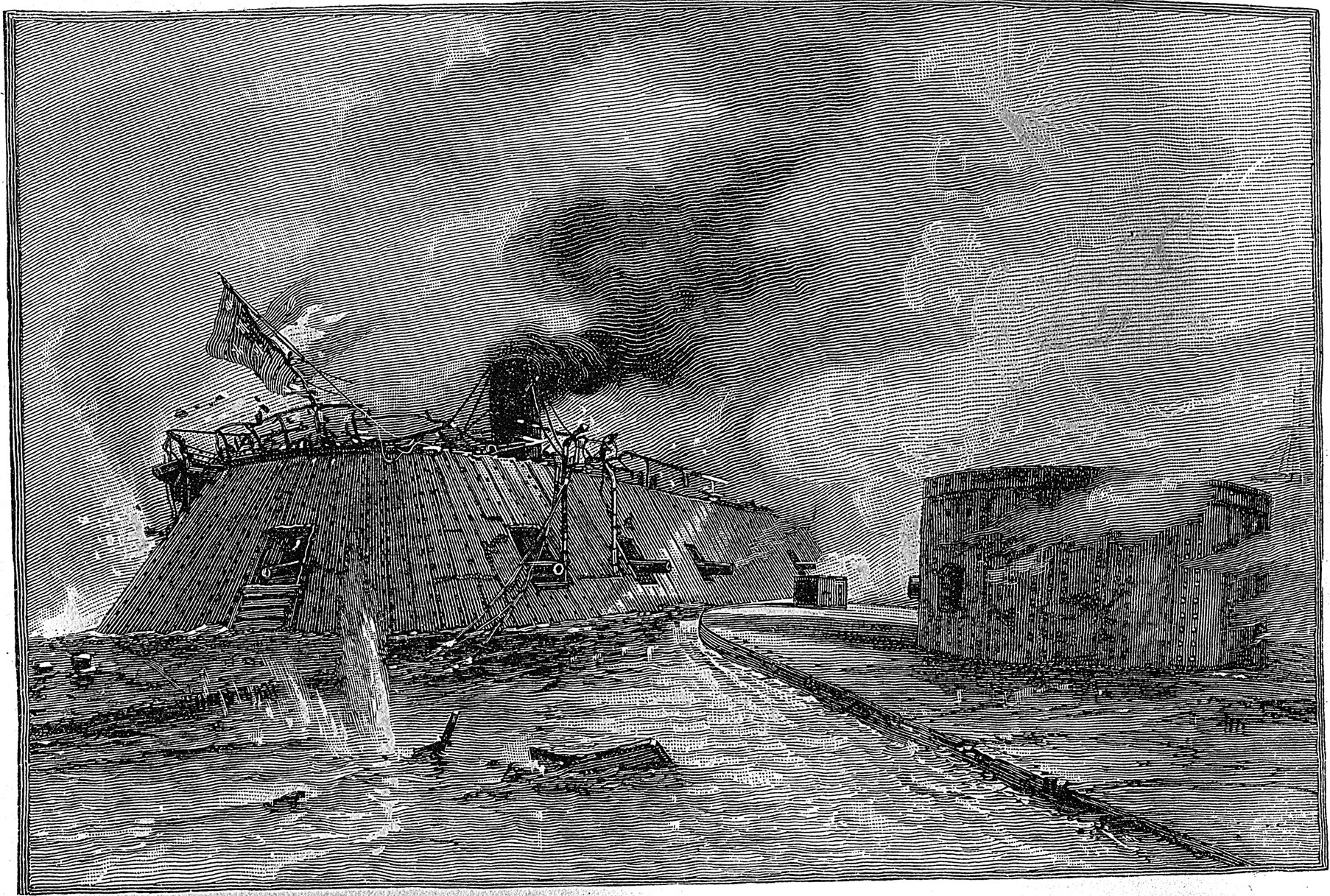

At first, Smith was the more preferred of the two. His first position was as a recruiter for the Confederate States Navy, which had only come into existence on February 20, 1861.The civilian in charge of the Navy was former United States Senator Stephen R. Mallory, who had been chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee before the war. Smith was appointed, along with Captain Samuel Barron and Commander Robert Pegram, to make a list of those Virginia officers who were departing Federal service. The three-man board then invited them to join Virginia’s state militia. They had a sizable list to go through—some 114 officers alone quit the Union Navy in the month of April.

After Appomattox

On April 2, 1865, with the war lost and his brother desperately seeking to avoid his own fate of surrendering the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Smith was ordered to transform his sailors back into soldiers for a last-ditch defense of Richmond. He managed to piece together 400 additional men for the trenches at Danville, Virginia, but did not join the defenders. Instead, he safeguarded Robert’s wife, Mary Custis, during the last week of the war.

Smith duly complied with the Union parole structure and returned home a private citizen at the age of 63. As with most Southern veterans, he took with him the effects of four years of war on his body and mind. Not in the best of health, he had to start anew at an unfamiliar vocation—farming—taking up residence on Acquia Creek near Richland, Virginia. The shift in professions was neither easy nor profitable.

Meanwhile, Robert assumed his own new position as president of Washington College. Their postwar duties and lack of money prevented Smith and Robert from visiting each other as often as they had done in the past. The last time the brothers came face to face was on May 28, 1869, when they worshiped together on Ascension Day at Christ’s Church. Two months later Smith died of liver failure, leaving what his brother sorrowfully termed “a sad gap in our family, a grievous affliction to me which I must bear as well as I can.” Much to his regret, Robert arrived too late to attend the funeral service in Alexandria.

I am new to Warfare History Network, in fact, today is my first encounter with your site. I joined immediately and I can’t tell you how very impressed and delighted I am with it all. Thank you so much!