By David H. Lippman

The four ships that raced into battle on December 13, 1939, off the mouth of the River Plate were, as historian and novelist Len Deighton tartly observed, “three different answers to the question that had plagued the world’s navies for half a century: what should a cruiser be?”

The British cruisers Ajax and Achilles were light ships with 32-knot speeds and 6-inch guns. HMS Exeter hurled 8-inch broadsides, while the German “pocket battleship” Graf Spee traded speed (26 knots) for armament (11-inch guns).

The newest of the three was Graf Spee, scuttled by its crew at the mouth of the River Plate. Laid down in 1932, she had been commissioned in 1936, the youngest of the three sister pocket battleships. She displaced 16,020 tons at full load, had a draft of 24 feet, and could reach a top speed of 29.5 knots in a pinch. The size of a heavy cruiser, she gained the name “pocket battleship” for her six 11-inch guns, which gave her a punch equal to a battlecruiser like Kriegsmarine sisters Scharnhorst or Gneisenau. She also had eight 5.9-inch guns as secondary armament, six 3.7-inchers, eight 37mm and 10 20mm flak guns. She also had eight torpedo tubes astern.

In war, however, the other two pocket battleships, Deutschland and Admiral Scheer, were less impressive. Deutschland sank only three ships in her 1939 cruise in the North Atlantic before running home. She was renamed Lützow by a nervous Adolf Hitler, who feared the propaganda losses of a ship named Deutschland being sunk. Both ships were sunk in their slips by the RAF in 1945.

HMS Exeter also went to the bottom, but not without a fight. Weighing in at 8,390 tons, she was launched at Devonport on July 18, 1929, and spent most of her first 10 years showing the White Ensign around the world. Despite her snappy appearance, she had weaknesses. She carried only six 8-inch guns, in accordance with 1920s disarmament treaties, and could carry only 1,900 tons of fuel oil. That limited her range to 10,000 miles at 11-14 knots. Historian Dudley Pope’s harsh assessment was that she had been built “so that she could be sold to a potential enemy.”

Exeter returned home to England after the River Plate and was a dockyard case for most of 1940. During that time, she was given more magazine stowage and ready-use ammunition lockers. She also added elevation to her 8-inch guns and gained new 4-inch antiaircraft guns and pom-poms. Masts to hold radar equipment were installed, but radar was never fitted.

She was escorting a convoy to Rangoon when Pearl Harbor was attacked and was ordered to join the battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse in Singapore. By the time Exeter reached Singapore, both Prince of Wales and Repulse had been sunk. She was sent back to Ceylon, escorting a convoy with survivors of the two ships. Exeter then sailed back to Singapore with reinforcements and down to Java to join “ABDA Float,” the Australian-British-Dutch-American naval command trying to fend off Japanese conquest of the Dutch East Indies.

This polyglot force fought under Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, a man of great charm and determination, but had no time to train together or even work out tactics or a joint signal code. When a vast Japanese force steamed down to invade Java, Doorman hoisted “Follow me” from his flagship, the light cruiser De Ruyter, and sailed out on the afternoon of February 27, 1942, to attack the Japanese, trailed by elderly warships manned by exhausted crews. The night battle turned into a nightmare.

With the advantages of coordination, night-trained lookouts, and the superb Long Lance torpedo, the Japanese tore apart the Allied force. Exeter was first to be severely damaged—an 8-inch shell tore through her B boiler room, killing all 10 men and knocking out six of eight boilers. Wreathed in steam and smoke, she dropped speed to 10 knots and wobbled out of line, depriving Doorman of one of his two heavy cruisers. The Japanese charged, sinking three destroyers and the two Dutch cruisers, killing Doorman.

The next evening Exeter steamed out to head for Ceylon for full repairs, escorted by the American destroyer Pope and the British destroyer Encounter. To fool the enemy, Exeter was to sail east, then north, then double back west. Exeter Captain Victor Gordon didn’t think he had a chance. He told his men there would be no air cover and that it was up to them and their escorts to survive.

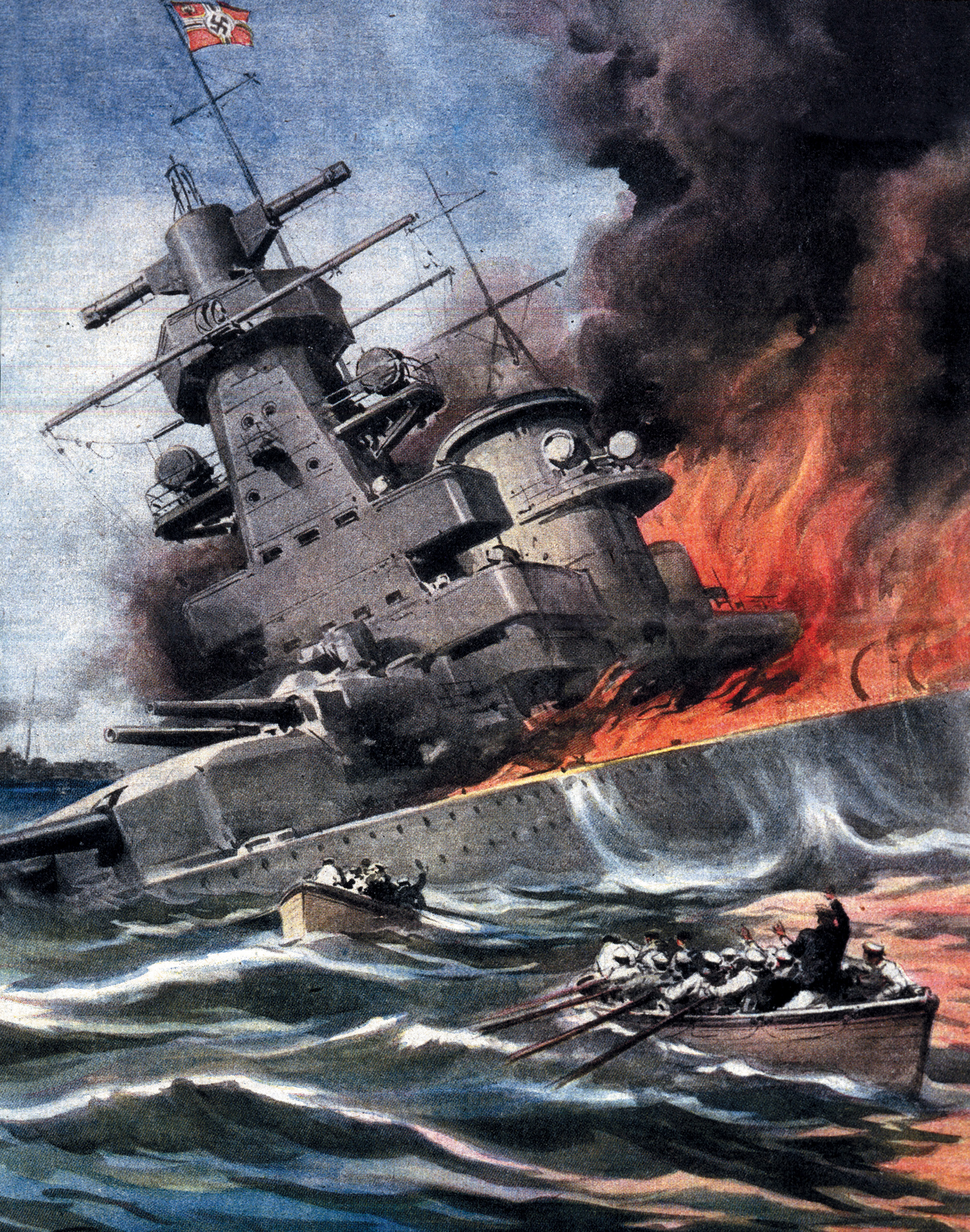

The following morning at 7:50, March 1, 1942, the three ships spotted warships’ masts. Exeter changed course to avoid them, but it was too late. The Japanese had intercepted Exeter with four heavy cruisers and two destroyers. Exeter cranked up her speed to 25 knots and the destroyers made smoke, but the Japanese were good shots. They immediately knocked out Exeter’s fire-control system and battered her with shellfire and torpedoes.

At 11:20 am, the Japanese blasted open Exeter’s boiler room, and she dropped speed to four knots. Exeter was doomed. Gordon ordered “abandon ship” at 11:35 am and opened the seacocks and flooding valves. While the crew pushed boats and rafts into the water, the Japanese continued their shelling. A Japanese destroyer fired a salvo of torpedoes into Exeter’s starboard side, and the veteran cruiser rolled over—providing the Japanese with dramatic photographs—and sank at about 4 degrees 38 minutes South, 112 degrees 28 minutes East, leaving the crew to the horrors of Japanese captivity.

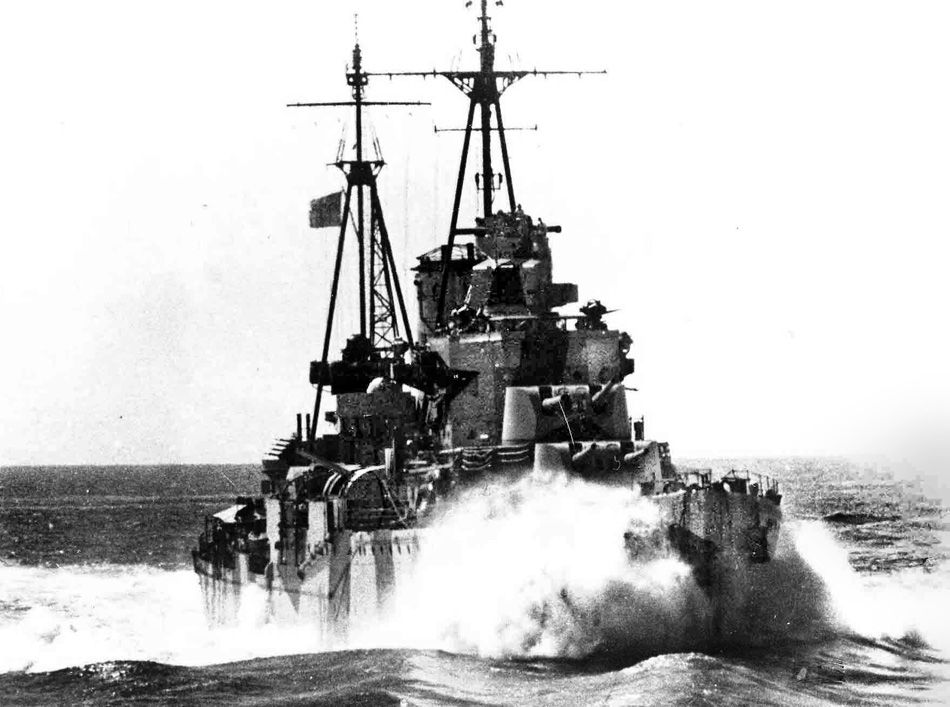

By comparison, Ajax and Achilles had “good” wars. HMS Ajax was launched by Vickers-Armstrong in Barrow in March 1934. She displaced just over 9,000 tons and had a top speed of 32 knots. A sturdy-looking ship, she had one massive, single-trunked funnel, which meant that her boiler rooms were interconnected and could be destroyed by a single shell.

After the River Plate battle, Ajax spent most of the war in the Mediterranean Fleet, seeing a great deal of action. At the Battle of Cape Matapan in late 1940, she helped sink three Italian heavy cruisers. During the German invasion of Crete, she intercepted a German-Italian convoy headed for the island and evacuated British troops from Heraklion. But the strain of constant Luftwaffe bombardment wore down the ship and crew. Sixty percent of her antiaircraft ammunition was fired off, and 30 of her 800 men suffered nervous breakdowns from the stress. Damaged by bombs, Ajax was pulled out for repairs, then helped bombard Vichy-controlled Syria in the British invasion of that French territory.

Ajax’s last major appearance of the war came on D-Day in Normandy, when her 6-inch guns easily destroyed the German Longues Battery off Gold Beach, impressing everyone with her accuracy. However, Ajax’s gunnery director had a competitive edge: the blind son of a French resistance worker had paced off the distances between the batteries and their control points, memorized the numbers, and these were radioed to England. When Ajax went into action, her gunnery officer had all the information he needed to send a 6-inch shell hurtling through the battery’s embrasures and observation slits, killing the defenders and leaving the guns relatively intact.

That proved to be a postwar boon to the local inhabitants, who restored the guns and turned the Longues Battery into a museum. The guns themselves, among the few survivors of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, became standard features for travel editors needing photographs of the Normandy beaches. The guns Ajax silenced have appeared in Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, and many other magazine articles on D-Day’s anniversaries.

HMS Ajax, however, didn’t make any of the celebrations. She was scrapped in 1949.

HMNZS Achilles was launched on September 1, 1932, by Cammell Laird in Birkenhead and was assigned to what was then the New Zealand Squadron in March 1936. A sister of Ajax, she replaced the older HMS Diomede, whose crew transferred to Achilles. She sailed to New Zealand and took part in the search for Amelia Earhart in 1937.

After her encounter with Graf Spee, Achilles spent most of 1940 and 1941 in the Pacific escorting convoys and hunting for German merchant raiders—freighters and liners that had been converted into auxiliary cruisers to prey on British shipping in waters distant from the Fatherland. With concealed guns, torpedoes, and mines, these ships cut a jagged swath through Britain’s ocean lifelines. Achilles pursued raiders named Atlantis, Pinguin, Orion, and Komet for two years to no avail.

These frustrating chases were ended in December 1941, when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the Emperor Hirohito’s men struck south, heading directly for Australia and New Zealand. Achilles spent part of 1942 escorting liners and merchant ships full of American troops headed for Australia and New Zealand, even Britain’s massive new Queen Elizabeth.

She missed the battles of Coral Sea and Midway, but escorted convoys to support the invasion of Guadalcanal. She was placed under American command in December 1942, and operated with American cruisers in the Solomons.

On January 5, 1943, a Japanese bomber blasted Achilles’ X turret, killing 11 Royal Marines and wounding 10 others. The bomb’s trajectory just missed exploding the cruiser’s magazine. Despite the destruction of her X turret, Achilles continued in action until March 22, 1943, when she reached England for repairs. She spent the next few months moored near the historic HMS Victory. Her X Turret was removed and replaced with flak guns.

But on June 22, while in dock, a gas explosion ripped through Achilles, killing 29 sailors at breakfast and injuring 60 more. Achilles was gravely damaged. With HMNZS Leander out of action from torpedo damage in the Solomons, New Zealand no longer had any cruisers in action.

So, Achilles’ crew was sent to commission the light cruiser HMS Gambia, which was loaned to New Zealand, and Leander’s crew was sent from America to Britain to put Achilles back in action with new tripod masts, new radar, and new antiaircraft guns. The cruiser left Portsmouth on June 2, 1944, slipping past gigantic armadas of ships heading for Normandy. When the Allies invaded France, Achilles was heading for Stromness for workup. She was ordered to the Mediterranean to support the invasion of Southern France, but by the time she reached Gibraltar the Germans were on the run. Achilles was ordered on to the 4th Cruiser Squadron of the British Eastern Fleet in Trincomalee, Ceylon.

Achilles sailed through the Mediterranean and reached Ceylon on September 13, joining a fleet that included British, Australian, French, Dutch, American, and even Italian ships. After a trip back to New Zealand to pick up a convoy of reinforcement, Achilles bombarded Japanese installations at Sabang and then joined Task Force 57, which was supporting the American invasion of Okinawa.

Achilles escorted carrier forces that attacked the Sakishima Group of islands off Formosa. After that, the whole force sailed to Okinawa, where Achilles and her cohorts came under kamikaze attack. When the island was secured, the British Pacific Fleet moved on to bombard Japan with battleship shells and carrier-based aircraft. Achilles provided antiaircraft cover and shelled Honshu.

After Japan’s surrender she came home to New Zealand for good on March 17, 1946, released from the British Pacific Fleet, and did a victory lap around the nation, with open days for the public at every port she visited.

In 1948, Achilles was sold to the Indian Navy and renamed HMIS Delhi. When India became a republic in 1950, she became INS Delhi. As Delhi, the cruiser took part in the Spithead Coronation Review of Queen Elizabeth II, as India’s representative ship, and served for a time as flagship of the Indian Navy.

When India took over Goa from the Portuguese, Delhi bombarded the port, her last action. In 1971, she was converted to a training cruiser.

On June 30, 1978, INS Delhi’s commissioning pennant was hauled down, and the ancient cruiser was paid off for the last time, having outlived so many of her contemporaries and junior sisters.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.