By Richard A. Beranty

The large number of Allied prisoners being funneled south to Rennes, France, following the D-Day invasion swelled the German transit camp to capacity so the decision was made to transport the men to permanent locations inside Germany. They had been captured from all points of the Normandy battlefield and marched 100 miles in the four weeks that followed.

Scores of POWs converged at the Brittany rail hub. The men were assembled into groups of 40 and led to wooden freight train cars. Their farewell ration from the Germans was a slice of wurst and a piece of cheese along with a small loaf of bread that required special instructions from their captors. “Drei tage,” they were told in German, “drei tage.” The message was not lost on the POWs. Make the bread last three days.

“There were hundreds of us, and it took some time to get all of us loaded, which made it a pretty long train,” explained Charlie Lefchik, a 24-year-old American who was captured by German forces on June 10, 1944. “Being already used to hunger, we figured that we could make the three days easily. But it turned out we were in those boxcars a lot longer than that.”

The train pulled away from Rennes just before dark on July 5 headed east, making progress only at night because of daylight patrols by Allied fighter planes. At morning the boxcars were dropped at a train siding, and at dusk the engine would return to move the cars to another location. The men were given water, wurst, and cheese once a day, and on the fourth day received the promised loaf of bread. With it came the same advice from the Germans: drei tage. The men’s cycle of misery continued for 23 days.

“One time during those 23 days we were put on a siding at dawn, and our train never moved for about a week,” Lefchik said. “For two days during that time they didn’t give us any water, and thirst is much worse than hunger. Being July, it didn’t take long for us to start dehydrating. During one of those nights it rained some, and one of the guys wiggled out a canteen cup between the bars and barbed wire over the small window opening in the corner of the car and caught some rain from the roof.”

The POWs found themselves locked inside a slow-moving French railroad car called the 40 and 8, a relic from World War I so named because it could ferry 40 soldiers or eight horses into battle. Originally built to haul farm produce, the narrow gauge boxcar measured 10 feet wide and 20 feet long, about one-third the size of a typical American boxcar. It became notorious in U.S. Army lore from doughboys a war earlier who thought it pure torture standing inside one, loaded with gear, while being moved to the front. They, however, were not required to sleep in it.

“We slept with 20 men on each side of the boxcar, but you had to sleep on your side to make room for 20 men,” Lefchik said. “If you slept on your back, you took the place of two men, which crowded that side of the car. We slept with our heads against the wall, and we overlapped our legs in the middle of the car.”

The Germans furnished the 40 and 8 with a can placed in the center of the car surrounded with straw. Lefchik said prisoners were allowed to empty it once a day. “The can was used for relieving ourselves and any waste matter if we had any since we hardly had anything to eat for so long.”

The loaves of bread continued every fourth day for another three weeks. Their caged torment finally ended on July 28 when the train reached its destination near Chalons in eastern France. The POWs had traveled nearly 700 miles by rail, averaging just 30 miles a day. They all suffered from the crippling effects of muscular atrophy as a result of physical inactivity.

“When we got off those boxcars we were so weak from lack of food and exercise that we had to lift our legs to get over the rails,” Lefchik said. “That’s when I noticed how thin I was. I could touch both of my middle fingers together under my thighs, and I could touch my thumbs at the top of my thighs with space in between.”

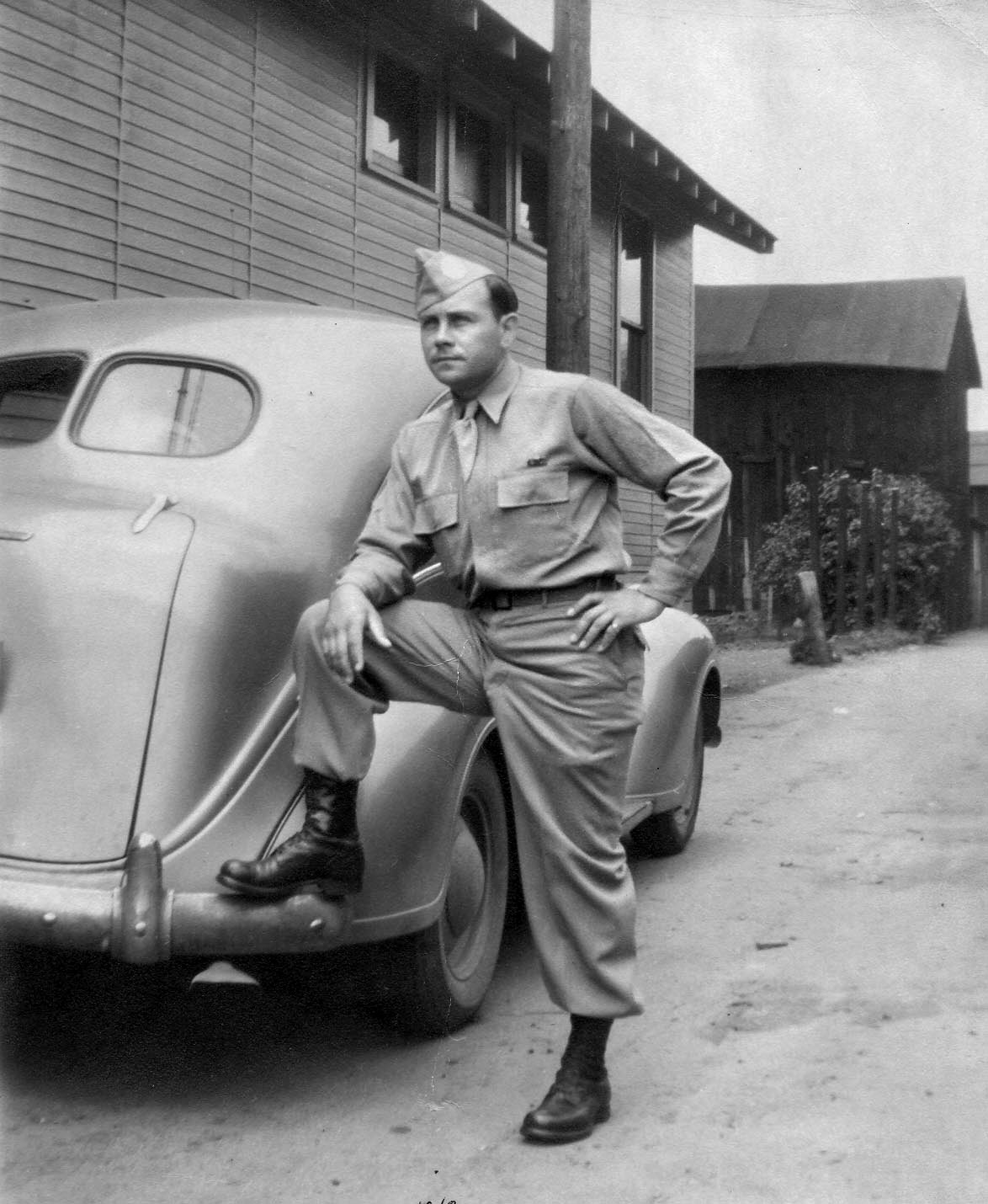

Lefchik’s hard luck ticket on the 40 and 8 was punched at 2:30 am on June 6, when he jumped into Normandy with the 82nd Airborne Division as a private in H Company, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment. Many planeloads of men in the final wave of D-Day landings touched ground miles away from their targeted areas because of thickening clouds and a spirited defensive effort on the part of alerted German gunners. Of the six U.S. airborne regiments to take part in Operation Overlord, the 507th PIR suffered the highest number of killed, wounded, or captured, including Colonel George V. Millett, Jr., its commanding officer, who was taken prisoner on June 9. It has been said that of the 78 busloads of regimental soldiers taken to their airbase at Barkeston Heath and Fulbeck prior to takeoff on June 5, only eight busloads of men returned from combat one month later. The tragic misdrop was Lefchik’s first parachute jump into combat, his 16th and final one of the war.

“I was surprised how well I could see the shapes of trees in the dark and the poles that were set up to keep gliders from landing,” explained Lefchik, who landed in a seemingly tranquil area of the region dotted with farms, fields, woods, and apple orchards. “I kept searching the ground for signs of the enemy, but there was none. I met up with some other guys, and we decided to stay put in some trees until daylight so we could find out where we were and what to do.”

Lefchick said an eerie haze covered the low ground at dawn on D-Day when they spotted a column of U.S. troops framed against the skyline on higher ground south of their position. “Watching them trudging along I suddenly recognized them as some of the men from my company, so I ran to join them as fast as my legs would let me.”

The group moved toward the sound of gunfire and found more men from their unit who had ambushed an enemy supply detachment, capturing eight Germans along with two vehicles that were riddled with bullets. “The trucks contained bread and jars of jellies. The bread was gray in color and very solid, different from the kind we knew. But with jelly it wasn’t too bad, and it curbed our appetite.”

Ahead of the men stretched a field blanketed by waist-high grass and weeds. “We were near the edge of the woods, and a German was coming down the slope from the right in a running crouch almost hidden by the grass. I raised my rifle and fired. Two other shots blended with mine, and the man dropped out of sight. We didn’t know if he was really hit or not, and if he was hit whose shot found its mark. That was the first time in my life that I shot at a human being.”

Toward evening on D-Day, Lefchik was ordered to an outpost on some higher ground along a hedgerow to watch for enemy activity. “I was there for about an hour when my lieutenant came by with five other troopers, and he told me to follow them. We followed a hedgerow to where it ended at the woods and scrambled up an embankment and followed another hedgerow to where it ended at an open field. I was bringing up the rear, and after going about 30 yards I saw an object up ahead in the field only a few feet from the hedgerow. It was a German soldier lying partially on his right side, no helmet, and the left rear part of his head was blown off. Directly across from him, half dug in and cowering in the hedgerow, were two German soldiers, blood on their faces and bloody hands held high. You could see the terror in their eyes as they pleaded with each of us as we passed by, ‘Nien. Nien.’ We kept going, figuring there was no danger from them in their condition.”

The enemy ruse worked as intended. Lefchik said in a short time they received gunfire from the two bloody Germans they had passed minutes earlier. “We lined ourselves up on a small bank and started firing at their position. One of our guys was hit in his elbow and was bleeding like hell. Someone put a tourniquet on it, and we got out of there and back to our unit, which was on the other side of a small and narrow road. Each of us took his turn going across. Since I was last in line, and it came my turn to go across, I didn’t go. I stayed about 10 seconds longer than the others, thinking, ‘What if the Germans saw us crossing at spaced intervals and sighted their weapons down the road on me.’”

The paratroopers stayed hidden in a copse of trees overnight and throughout the following day, becoming some of the first Americans to experience combat in Normandy’s hedgerow country. While the centuries-old method of land division was alien to U.S. soldiers, it represented a tactical paradise to its four-year occupiers. “The fields in Normandy were divided by hedgerows, not fences like we have,” Lefchik said. “They were mounds of dirt piled about two feet high with thick hedges about five or six feet high growing out of the mounds of dirt. They had openings, usually at the corners and sometimes in the middle. The openings were only wide enough for one person to go through at a time.”

As daylight faded an attempt was made to cross German lines and try to reach U.S. forces fighting inland, but their prisoners posed a problem. “The Germans were being kept in a little barn across the road behind us. Even though it was war, none of us could dispose of them by shooting them in cold blood. Our only alternative was to leave them.”

The men waited until dark and quietly left the area and their captives behind. In single file they cautiously moved away, following several hedgerows to a field and its bordering woods when the column came to a stop. “We were hunkered down, and one of our officers came down the line headed for the rear. In a few minutes he came back followed by two other troopers. After about 15 minutes we heard a muffled cry, hardly audible, of pain and agony. Then word came down to us that the head of the column happened on two sleeping Germans and the two men brought up from the rear sneaked up on them as they slept and knifed them.”

The column next entered an orchard where the men were met with a German challenge they could not answer. They began to ease their way back when Germans suddenly fired in their direction. “Most of the men ran back the way we came while the rest of us ran to the opening in a hedgerow,” Lefchik said. “One trooper couldn’t wait his turn to go through, so he ran in a short circle to pick up speed and like an airplane taking off ran toward the hedgerow and soared up and through the top of it.”

They followed a ditch that ran parallel to a blacktop road and encountered a German truck with intricate wires leading away from it to a nearby farmhouse. “It must have been a communication truck because it had a spider web maze of wires coming from it. We went through the wires without getting hung up, crossed the road, and headed for a gully in the center of a field with small trees and bushes. Dawn was breaking so we decided to hide out there during the day. We could hear the Germans who were already awake and on the road above us yelling orders as they prepared to move out.”

Hidden from German eyes, the small group of Americans spent the long daylight hours of June 9 hiding in the woods. The men got little sleep because of artillery fire throughout the day. Guns boomed from one side and then the other, Lefchik said, and about two or three seconds later they heard the fading “sh-sh-sh-sh-sh” sound of shells passing over their heads. Realizing the coming night might be their last chance to reach U.S. lines, they decided once again to try their luck solving Normandy’s labyrinth of hedgerows.

“As soon as it got dark we were just like rats coming out of their holes,” Lefchik said. “We moved in single file without incident until just before daybreak. Our column was crossing a field and entering some woods, and the two front men came running back out. They met Germans just waking up after bedding down in the woods.”

German guns fired, and a man beside Lefchik fell to the ground, killed instantly. Lefchik and five others raced to the nearest cover, some bushes and weeds, while the rest of the column fled the way they had come. The men threw a grenade into the woods, and the Germans responded with three of their own. “Everything was quiet for a while, and then I heard a pop. A German flare was shot out over the field. As the flare burst, the field was covered in a brilliant light that came down slowly on a small parachute.”

The Americans remained motionless, partially exposed to the enemy and trying their best to absorb and blend with everything the bushes and weeds had to offer. Over the next several minutes two more German flares were sent skyward. “They have a machine gun set up at the corner of the field and pointed in our direction,” said a paratrooper in a hushed tone during one of the dark intervals. Desperately lost and on the run behind enemy lines for 100 continuous hours, one of them yelled “kamerad” from inside the bushes and was told by the Germans in broken English to come out.

“Dawn was beginning to break, and we had no place to go with the Germans in the woods and flares being shot out over the field,” Lefchik explained. “Our only recourse was to surrender even though one of our men said, ‘Don’t trust them.’ But we had no choice. As the saying goes, discretion is the better part of valor, so we had to take our chances.”

Over the next five days the men were kept inside a small barn that became a collection point for other U.S. prisoners, mostly airborne, who were captured after D-Day. On June 16 they started a 10-day march to the transit camp at Rennes, surviving on what little rations the Germans provided and the gratitude and generosity shown by French civilians they met along the way.

“Several people from a house we were passing stopped the group and asked the guards for permission to feed us,” he said. “They brought out vegetable soup in large pots, the best and most delicious food I have ever eaten. It had everything in it: potatoes, carrots, beans, onions, and also milk. We were like hogs slopping at the trough, eating from anything that would hold soup. From all our hunger and shrunken stomachs it was a wonder that none of us got sick because we certainly gorged ourselves. Another time we were fed by the French and one of the ladies came up to me and gestured if she could have the little American flag on my right shoulder. I gestured for her to cut it off, which made her happy. I even saw someone standing back in the doorway of the house waving a small American flag.”

The men were marched mostly at night, dictated by whether the sky was clear or overcast and the presence of Allied aircraft. “There were times during the daylight marches we would come upon a section of the road that was peppered with holes about eight or 10 inches in diameter where fighter planes did some strafing,” Lefchik said. “About 50 yards farther on we would come upon a vehicle in a ditch that was strafed and all burned up and full of bullet holes.”

Housed in barns or any other outbuildings encountered along the way, the dusty and hungry prisoners arrived at Rennes on June 26, where they remained for eight days. Lefchik said the transit camp provided the best rations he received from the Germans since his capture 16 days earlier. Breakfast was two slices of bread with butter and jam and a small dipper of sweetened tea. Dinner was one dipper of thick onion, potato, and cabbage soup. Supper was the same. It was fine dining, he said, compared to what lay in store when the prisoners pulled out of Rennes on the 40 and 8. “I don’t know how or why we didn’t go crazy all the time we spent in those boxcars starving for food and thirsty for water,” Lefchik remarked about their 23-day confinement.

The prisoners were badly malnourished when the train arrived at Chalons, and it took some time for the Germans to unload them all. Rations improved somewhat, consisting of hot tea for breakfast, a dipper of watery soup for dinner, and the same for supper along with a loaf of bread shared by four men. Hunger had no relief and trying to end it did not always work. “One of the boys at the head of the line got his one dipper of sauerkraut soup and immediately ran back to the end of the line, eating his sauerkraut soup as he moved forward with the line. He got seconds, and again he ran back to the end of the line to see if he could get more. He got a third helping, but while he was eating it his body rebelled because of his shrunken stomach and he lost all his food.”

The prisoners were housed inside a three-story building with blown-out windows. After 18 days they were loaded into boxcars bound for Stalag XIIA at Limburg, Germany. “This time they gave us a loaf of bread and a half quart of meat, which was quite a treat at that time,” Lefchik said.

The Limburg camp near Frankfurt was not capable of handling such a large number of prisoners, so the men were kept under circus-sized tents with straw for bedding. For the first time they received Red Cross parcels, a godsend to POWs, with their variety of foodstuffs. Most appreciated was not the assortment of delicacies such as powdered milk and raisins, but rather the cigarettes, which became standard currency for purchasing power in German camps throughout the war. The highest priced commodity was a two-ounce container of American coffee valued at 40 cigarettes. “Each item in the Red Cross parcel had a price for a certain number of cigarettes. The men who smoked could sell some of their items for cigarettes because money was of no use in the prison camp. I didn’t smoke, and if I found a pack or two in my parcel I kept them in case I wanted to buy an item.”

On September 5, Lefchik and a trainload of other prisoners were transferred from Limburg to their final destination, Stalag VIIA at Moosburg, Germany, which was a sprawling complex north of Munich that contained thousands of POWs from many different countries. Double strings of barbed wire fencing kept the nationalities apart inside their own separate compounds of one-story wooden barracks. Unlike Hollywood’s depiction of prisoner life, Lefchik said officers were not housed with enlisted men, and Germans were extremely proficient at running the camp. “The nonsense you see on TV and in movies never happened,” he said.

The men slept in bunk beds stacked three high on a burlap mattress stuffed with straw. Four slats held the mattress in place but were not nailed down. Lefchik said one had to be careful when moving not to fall through and onto the man below. Still, the top rack was the most desirable of the three. “Guys tried to get the top bunk because every time you moved around there was always dirt falling out of the burlap on the guy below,” he said. “And because of all the straw in the mattress a lot of fleas and lice did too.”

POWs were provided showers once a month—50 men at a time. They were marched under guard to a facility that served the entire camp. They carried only their wash cloth and a cake of soap with them, placed their clothes and shoes on numbered hangers that were hung on racks. Next door to the showers was a gassing chamber, and the racks were placed inside of it. “After showering we stood around to dry off and waited for our clothes to be fumigated,” Lefchik explained. “When they took our clothes out of the gas chamber they let them air out a little and then started calling out the numbers on the hangers. You had to remember your number to get your clothes. We would dress then go back to the barracks for more dirt, lice, and fleas.”

Moosburg was the distribution point of Red Cross parcels arriving from Switzerland, and each POW received one per week. Men who experienced confinement in German camps largely credit the packages for their general well being even in ways beyond nutrition. To heat water for coffee the men used a POW invention made from Red Cross tins called a “blower,” a wood-burning stove about 18 inches long. The hand-operated, crank and pulley rigged device turned a wheel of metal blades that produced airflow, which fanned a small fire to cook over. British soldiers, some of them prisoners since the fall of Dunkirk four years earlier, devised the gadget that created fire “like a blowtorch.”

“Our evening ration was seven men to a loaf of bread, two cooked potatoes for each man, a piece of wurst, and a piece of cheese,” Lefchik said. “We would combine that with some of the contents from the Red Cross parcels and make stew on the blower.”

Germans also gave the men soup at times—cabbage and potato or pea—along with another type that was less appetizing but more memorable. “It was some kind of green vegetable cooked in greasy water with no taste and already getting cold when we got it. We called it hedgerow soup because it looked a lot like the hedgerows that we fought among in Normandy.”

In early October Lefchik was put in the camp hospital for an infection of his right foot, which had swollen to nearly twice its normal size. The next day German doctors treated it with an early form of anesthetic skin refrigerant called ethyl chloride to control pain as a prelude to surgery.

“They told me not to move, and one doctor held a large hypodermic needle and the other doctor pointed to a spot between my big toe and the one next to it. He wanted him to squirt liquid from the needle three feet away to the spot he gestured. As he squirted the liquid the other doctor blew on it and froze that part of my foot. Then he took a scalpel and made an incision between my toes, and the blood and infected matter just poured out. Then they started to squeeze my leg from the calf down to get it all out. It was very painful. I was in the hospital for six weeks, and every day I had to soak my foot in hot water that contained some kind of medicinal liquid that helped draw out the infection. At first I thought maybe I would lose my foot, but it turned out okay.”

Willing to haul brick and clear rubble for a chance to leave camp and barter with German civilians, some POWs volunteered to help with the heavy work of cleanup following an Allied bombing raid on nearby Munich. They traveled from Moosburg on 40 and 8 boxcars, providing one solution to Germany’s manpower shortage brought on by the strain of war. It was not uncommon for prisoners to be sent to cities and farms throughout the country and used as manual labor. In Munich guards were lenient with POWs who traded with civilians, and securing bread to eat was a top objective.

“We got two loaves of Vienna bread for a pack of cigarettes because Germans liked American cigarettes,” he said. “We got two loaves of bread for a bar of soap because our soap lathered so well and women wanted it for themselves and their kids.”

Prisoners faced a challenge trying to smuggle items into Moosburg upon their return. Some men sewed pockets on the lower inside of their overcoats and entered the stalag with coats unbuttoned so not to give guards notice of their concealed contraband. “Since I was a paratrooper, I had my pants bloused in my boots and put a loaf of bread in each pant leg and you couldn’t tell they were there,” he explained. “We had to be careful when going back into camp. If they noticed us bringing anything in, they would take the whole group of 50 men off to the side and take everything from them.”

Lefchik left Moosburg in late March to work on a farm and spent his final five weeks of imprisonment performing the chores normally done by German men. He and 22 other volunteers were taken under guard in a civilian passenger train to the tiny hamlet of Amberg and assigned to surrounding farms. Hard work, fresh air, and farm food allowed the men to regain some vigor after months of inactivity and a lacking diet. They worked and ate at the farms but did not sleep there; instead they were kept overnight in a village house with barred windows. Every morning two German soldiers unlocked the door to the building and escorted the prisoners to their respective farms. At day’s end they were gathered from the farms and returned to the house by the same two guards.

“Women were in charge of the farms in the absence of their husbands, and they all had a young Ukranian girl to help them,” Lefchik said. “They were almost like prisoners, brought there after the Germans overran Ukraine. The lady I worked for had a girl named Varga, about 15 years old, and she helped me to communicate since I could understand Slovak, which is close to the Ukrainian language.”

One evening in late April, their final night as POWs, the 23 men lay awake in the house and listened as German guards returned well after dark, quietly unlocked the door, and fled. American ground units were advancing toward the area, and German forces were in retreat and had been for some time. U.S. tanks rumbled in the distance and occasionally fired their machine guns while the men stayed inside their confines. When day broke they gathered outside, and soon a U.S. spotter plane flew overhead making two circles above them. Not long afterward a reconnaissance unit from the 10th Armored Division arrived in a fast-moving, gun-mounted jeep and liberated the men at 12:25 pm, Friday, April 27, 1945.

“The guys in jeeps were going through the small communities to see if they would meet any German resistance,” Lefchik said, “and if they did, tanks and half-tracks on the outskirts of town would come in and wipe them out. We knew the war was coming to an end because every night we could hear German soldiers walking by our house moving back. The three men inside the jeep couldn’t take us back all at one time, but they did take us back in two loads. We were all over that jeep—on the fenders, on the bumpers, the hood, and all over the back of it. They took us to a half-track that was waiting on the edge of town and then to a command post. From there we got on any kind of vehicle that was moving to the rear away from the front. As we were moving back, we passed large fields that were filled with thousands of German prisoners. It really was a mass of humanity.”

Lefchik returned to the United States on a liberty ship from Camp Lucky Strike at Le Havre, France, and was given a 60-day convalescent furlough, a customary practice for returning POWs, along with a mental and physical evaluation required by the Army prior to discharge. In 1951, his claim for benefits under Section 6 of the War Claims Act awarded Lefchik $322 for time spent as a POW, equivalent to about $3,000 today. Before he died at age 93 in his hometown of Ford City, Pennsylvania, in 2013, the retired factory worker reflected on the fear and uncertainty one soldier felt prior to battle.

“When I went into combat I imagined all kinds of things that could happen to me, such as being killed, wounded, or crippled,” he said. “My mind was racing with questions. Will I make it safely to the ground? Will I be able to see where I’m going in the dark? Will there be Germans on the ground waiting for us? But never once did I imagine being captured and taken prisoner. That was really the unexpected.”

Richard A. Beranty is a frequent contributor to WWII History. For additional reading he suggests Down to Earth: The 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment in Normandy by Martin K.A. Morgan.

Thank you for sharing this account of Charlie Lefchik’s wartime service. Every one of these men deserves to have their story told and remembered.