By William E. Welsh

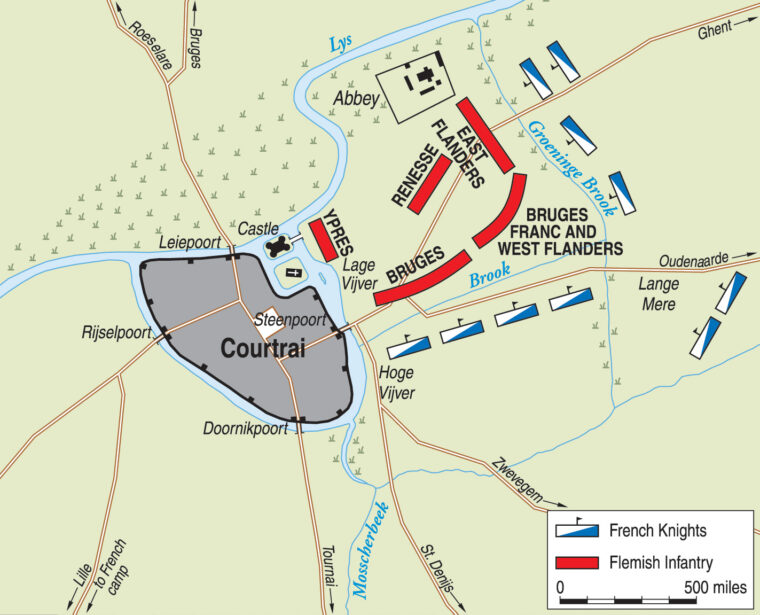

The Flemish infantry fidgeted under the sweltering sun as they stood shoulder to shoulder in a field east of the town of Courtrai on July 11, 1302. Their line formed a grand curve that stretched from the River Lys on their left to the gray walls of the town on their right. More than 11,000 heavily armed members of the Flemish Communal Army had assembled to resist the effort of French King Philip IV to forcibly annex the county of Flanders to his vast realm. A sense of unease emanated from the unseasoned troops, but they took heart because they felt they were resisting a tyrant.

The Flemish watched keenly as 3,000 French knights and squires resplendent in their armor under brightly colored banners formed ranks in preparation for their advance across the floodplain. Some of the veteran horsemen had come from as far away as the lands bordering the Pyrenees to fight the unruly Flemish. Many of the knights sported golden spurs won in lavish tournaments in which they honed their martial skills. They had come to crush a rebellion that had become increasingly brutal in the previous weeks following the massacre in May of French troops billeted in the Flemish town of Bruges 25 miles east of Courtrai. Their confidence was evident in the proud boasting made by each knight of how many Flemish he would slay that day. Most expected the Flemish to scatter when they made their charge. Once that occurred, it would simply be a matter of killing the commoners and taking the leaders of the revolt back to Paris, where the king could decide their fate.

The banners that waved above the Flemish Communal Army were made by the textile guilds of the towns. Although they differed in the symbol that represented their respective guilds, they all displayed the Rampant Lion with outstretched claws and its wildly curled tongue. The soldiers beneath the banners kept their fear in check. They trusted that God would put victory in their hands. Chronicler Jean de Brusthem wrote that minutes before the battle began the Flemish soldiers were “rejoicing and excited, roaring in the manner of lions.”

At noon the French sent more than 1,000 crossbowmen forward. Their purpose was to inflict substantial casualties on the Flemish ranks from a distance so that the enemy would be substantially weakened by the time the cavalry began its terrible charge. On the French right flank, 52-year-old Count Robert II of Artois, the commander-in-chief of the French forces that day, surveyed the battlefield. The count had been on many campaigns during his lifetime, which had taken him far from his home in the county of Artois adjacent to Flanders.

The war between the French crown and the county of Flanders was by then in its fifth year. Although outnumbered, Artois was confident that his heavy cavalry would shatter the Flemish line on contact. In a council of war held before the French deployed for battle, Artois scolded 52-year-old Godfrey of Brabant, Lord of Aarschot, who warned Artois not to underestimate the Flemish. Artois reminded Brabant that lowly militia was no match for French cavalry. “A hundred horses are worth a thousand men,” said Artois. “What then hast thou to fear? Turn and look; these valiant men will not abandon thee.”

By the late 13th century, Flanders had become a thriving area of commerce rivaling northern Italy. Its count was a vassal of the king of France and therefore had to adhere closely to the instructions given him by one of the most powerful monarchs in Europe. The commerce in Flanders was centered on the textile industry. The Flemish imported wool from England and grew their own flax from which they made clothing for people living in England, France, Germany, and Italy.

The merchants who financed the textile industry formed a wealthy class known as burghers, while the workers organized in guilds representing specific trades formed a large and vocal group of commoners. The burghers controlled taxation, and for obvious reasons the burghers and the commoners were often at odds. The burghers applied heavy taxes to the guilds and to individual consumption, and the commoners sought a greater voice in their affairs and relief from what they perceived as exploitation.

The Count of Flanders derived his power historically from land holdings, and he often found himself at odds with the burghers, who sought to protect financial and political interests that were tied to the flourishing clothing trade. An interesting political dynamic arose in which the burghers appealed directly to the king of France for relief from the policies of the count, while the commoners appealed directly to the Count of Flanders for relief from decisions of the burghers.

Guy of Dampierre was a reactionary who adhered strictly to the conservative feudal system and failed to appreciate how the common people might help him enhance his strength politically and militarily. Before the reign of Philip IV, the Flemish counts had ruled with a considerable amount of autonomy. But when Philip IV ascended to the throne in 1285 at the age of 17, he took a personal interest in the affairs of his vassals and their territories so that he might squeeze the most political, economic, and military benefit out of them for his realm. Known as “Philip the Fair” for his good looks, the young French king was tall and handsome. But his outward beauty belied his inward sinister nature. In his dealings with others, particularly his vassals, he proved himself to be haughty, shrewd, and vengeful.

Flanders had become politically unstable even before Philip took the throne. In the 1280s, fractious disputes developed in Flanders, and there was occasional rioting as burghers and commoners clashed over various political and economic matters. Although Count Guy sought to ameliorate the injustices suffered by the commoners, his attempts to impose indemnities on them for the damage that occurred during the uprisings only served to further alienate the working class. When Philip the Fair came to power in 1285, he and his ministers actively intervened in Flemish politics in order to undermine Guy’s authority.

On January 7, 1297, the Count of Flanders entered into an alliance with the King of England. Two days later, Guy sent word to Paris that he was no longer willing to serve as Philip’s vassal and was declaring Flanders independent. Philip ordered Guy arrested, and the French king ordered Count Robert of Artois to mount a military expedition to Flanders to crush the Flemish rebellion. Artois was the best general in France at the time.

The first clash of the Franco-Flemish war occurred at Veurne on August 20, 1297, and resulted in a French victory. Since Count Guy was too old to lead troops into battle, he entrusted his army to an ally, Count Walram of Jülich. Count Walram, led an army comprising troops from Flanders, Brabant, and various north German principalities. The French captured and executed Count Walram as a warning to other foreign nobles not to assist the Flemish.

Having just concluded an expensive war against England, Philip the Fair had trouble financing military operations in Flanders. For this reason, he was not able to field an army to resume operations in Flanders until 1300. This time the army was not led by Robert of Artois, but by the king’s brother, Count Charles of Valois. Count Guy’s health was failing, and he transferred the title to his son Robert. With half of Flanders already conquered in the previous campaign, Valois had no problem overrunning the remainder of Flanders in just a few months. Both Guy and Robert were captured and sent to Paris.

Following the collapse of military resistance in Flanders in the spring of 1300, the French king instructed his ministers to abolish the title of Count of Flanders and make the county a crown land. To administer the new crown land, Philip the Fair appointed Jacques de Châtillon to oversee it. Châtillon was a narrow-minded reactionary who raised taxes in an effort to increase the king’s annual revenue.

In May 1301, Philip the Fair visited Ghent and Bruges. The Flemish guild workers appealed to the French king to ease taxes. Philip obliged, but the burghers did not comply, and the king did not intervene on the commoners’ behalf. The workers in Bruges were particularly incensed.

In the year following Philip’s visit to Flanders, two prominent guildsmen in Bruges, Pieter de Coninck, a weaver, and Jan Breydel, a butcher, organized the commoners in the town. The two leaders of the commoners in Bruges arranged representation for the guild members on the town council. French bureaucrats in the town reported to de Châtillon that the firebrands were working to have taxes decreased and that their followers were agitating in the streets, and for these reasons the governor ordered Coninck and Breydel arrested. A mob subsequently freed them from prison, and the two leaders and their followers then decided they had no recourse but to seize control of the town government from the French bureaucrats.

On May 17, 1302, de Châtillon brought a force of 800 infantry and 120 mounted men-at-arms to Bruges to restore order. That night Coninck and Breydel led an uprising in which the commoners attacked the French troops in the homes where they were quartered. During the course of the slaughter that night, which became known as the Bruges Matins, the townspeople of Bruges killed about 300 soldiers and 90 men-at-arms. The survivors, one of whom was de Châtillon, fled west.

The people of Bruges armed themselves for battle with the French and called on the other major towns in Flanders to join them. Since neither Coninck nor Breydel had the stature or experience to lead an army into battle, they cast about for a leader. One individual who expressed a keen interest in leading the Flemish Communal Army against the French was 25-year-old William of Jülich. The young prince was eager to avenge the execution of his uncle, Count Walram, following the Battle of Veurne five years earlier.

The Count of Flanders had authority to call up the Flemish Communal Army, but with Count Robert in prison in Paris William of Jülich served as the de facto count and mobilized the army for battle. The Flemish Communal Army was decentralized. The town guilds maintained arsenals that stored weapons and supplies for times of war.

Although the majority of the troops were militia, a small core was professionals trained in the use of either pikes or crossbows. Most of the militia was armed with the goedendag, a five-foot wooden staff with a thick iron spike at the top. The inexpensive goedendag, which any commoner could make at home or in his workplace, could be used to knock a knight from his horse and stab him through his plate armor. The Flemish militiamen generally could not afford chainmail tunics but did have open helmets and mail gloves.

Philip IV was irate when he learned of the attack on the French corps sent to restore order in Bruges. Knowing that Artois had defeated the Flemish Communal Army in a major battle once before, he decided to give him command of the French army that would punish the Flemish for massacring the royal troops in Bruges.

Artois began assembling his army in Arras in late June. His first objective once the army was assembled would be to march to Courtrai, which served as a gateway to central and eastern Flanders. A small French garrison in Courtrai was dangerously exposed to Jülich’s Flemish army, which was at that time being reinforced with troops from all parts of Flanders.

While he waited for troops to arrive in Arras from all parts of France, Artois dispatched a force of 1,500 led by French Constable Raoul de Clermont to reinforce the French garrison at the walled town of Cassel, which lay west of Courtrai. Clermont had orders to rendezvous with Artois near Courtrai once the commander-in-chief advanced on the main objective.

For his campaign against the French, Jülich was able to recruit 11,200 soldiers. The Flemish army, which was divided into three main corps, arrived at Courtrai on June 23 and laid siege to the town, which was held by 234 French troops. Heavily outnumbered, the French garrison abandoned the town and withdrew to the relative security of the castle to await relief.

It would be more than two weeks before relief arrived. On July 9, Artois and Clermont arrived outside Courtrai. The combined French army totaled 4,300, of which 3,000 were heavy cavalry and 1,300 infantry. The largest contingents came from the County of Artois and from allied regions adjacent to Flanders such as Brabant and Hainault, but the army did include substantial contributions from southwestern France. The infantry were mercenaries from Navarre and Guyenne and were commanded by Jean de Burlats, Seneschal of Guyenne. The majority of the infantry were crossbowmen, but there also were 300 light infantry armed with javelins. The highest quality troops in Artois’ army were recruited from crown lands such as Champagne, Normandy, and Ponthieu. Each of these regions contributed about 200 knights and squires, many of whom were veteran troops, to the army that arrived outside Courtrai.

Artois ordered a mixed force of cavalry and infantry to assault the west gate of the town, but it was easily repulsed by the Flemish heavy infantry, which had a large force of skilled crossbowmen posted on the battlements. With no siege equipment in his baggage train, Artois had no choice but to order his scouts on the following day to reconnoiter the south bank of the Lys for a suitable place to offer battle to the Flemish Communal Army. To assist the relief force, the Viscount of Lens, who commanded the French garrison, on the night of July 10 ordered several of his men to signal the relief army using torches that the most advantageous ground for a fight was the Groeninge Field that bordered the town to the east.

But the Groeninge Field, like all of the land adjacent to the town, was marshy land that was not well suited for cavalry operations. This didn’t matter much to the French, though, who believed that once the Flemish militia saw a professional army arrayed against them would retreat and disband.

The marshy character of the Groeninge Field was not its only drawback. Another significant drawback was that the field was surrounded on all sides by water courses. To the north of the field was the Lys River, to the west was a large stream that flowed into the river, to the south was the Great Brook, and to the east was the Groeninge Brook. The attack plan, as envisioned by Artois and his lieutenants, was for the cavalry to attack across the two brooks. The brooks would break up the momentum of the charge and, if the cavalry did not cross the brooks and reform quickly, make it vulnerable to counterattack. Nevertheless, it was a risk Artois was willing to take to carry out the king’s order to annihilate the Flemish army.

Early on the morning of July 11, the Flemish army filed out of a narrow gate in the east wall and deployed for battle. A corps composed of 3,000 men from East Flanders took up a position on the left near the Lys River. Jan Borluut, a wool merchant from Ghent led the corps. The 3,000-man Bruges Franc Corps, which was recruited from the villages around Bruges, held the center. The Bruges Franc was deployed in a curve connecting the two corps on the right and left that were deployed perpendicular to each other. The Bruges Franc men were led by 30-year-old Guy of Namur, who was a younger son of Guy of Dampierre. The largest corps, which numbered 3,500 men from Bruges led by William of Jülich, held the right.

Two smaller units of infantry were stationed in the rear of the Flemish army. A 1,200-man division from Ypres was deployed around Courtrai Castle to contain the French garrison, and a 500-man division was positioned behind the Flemish center as a reserve. The reserve was led by Lord Jan van Renesse of Zeeland, who had the distinction of being the Flemish commander with the most battle experience.

Artois called a council of war to consider how the French attack should proceed. He had not ordered a complete reconnaissance of the field of battle, and therefore there was no discussion of the two types of obstacles, namely the marshland and streams, that would hinder a successful cavalry charge. If the cavalry attack was interrupted or too slow, it might allow the Flemish to counterattack the French cavalry when they were in the process of crossing the streams. But Artois and his supporters were blind to the threat. Artois approved Burlats’ suggestion that the crossbowmen be allowed to shower the Flemish line with their iron-tipped bolts. The commanders left the meeting with the understanding that the cavalry would charge at the most opportune moment.

The French cavalry, which was organized by region, was divided into 10 divisions with 300 horsemen in each. The more heavily armored knights were in the front rank, while the less well equipped squires were behind them. The knights attacked with 13-foot-long lances braced under their arms. Once their lances were broken or lost in combat, they resorted to using their swords. When the cavalry attacked, it did so not at a gallop but at a trot in tightly packed ranks.

Namur knighted about 30 guild workers that morning who had shown valor in various situations during the Bruges Matins and in the weeks afterward. Jülich sent his 320 crossbowmen forward as skirmishers, and they took up positions in the tall grass behind the streams. He had word passed through the ranks that no man was to stop fighting to plunder the enemy. If any soldier saw another disobey the order, he was to slay him.

To strengthen the morale of the troops, Jülich sent his horse to the rear and ordered the small number of other nobles on horseback to do the same. Jülich then turned over command of the army to Renesse because he believed the Zeelander was the best qualified to issue orders in the heat of battle.

Seeing the French deploy for battle, the banners representing the various guilds and towns were unfurled. In the rear of the Flemish army, Renesse also ordered his banner unfurled. Renesse’s banner was emblazoned with a black lion on a gold field. Some of the French nobles recognized the banner, and they realized for the first time that the Flemish army had a capable leader.

Despite the intense heat, the spirit of the Flemish troops ran high. They traded stories about the depredations that the French had inflicted on the Flemish people and, in so doing, increased their lust for revenge against the unwelcome conquerors.

Namur walked to the front of the army and said, “Beware, noble Flemings. Stand firm because the enemy will ride toward you with much force. Call upon the help of God. He will certainly stand by us.”

After Renesse finished speaking he returned to his position with the reserve, and Namur and Jülich both took up goedendags and joined the ranks of the infantry. Jülich took up a position with the Bruges Corps on the Flemish right, and Namur joined the ranks of the men from East Flanders on the Flemish left. Viewed from the French line, the tightly packed ranks of Flemish with their sharp-edged weapons gleaming in the sunlight were a sobering sight.

Artois had grouped his 10 divisions into left and right wings and a reserve corps. Artois took up a position with the four divisions that constituted the right wing opposite the Groeninge Brook. Constable Clermont led the four divisions in the left wing, which formed opposite the Great Brook. Behind the junction of the two lines was a reserve corps composed of two divisions under the co-command of Count Guy of St. Pol and Count Robert of Boulogne.

The French crossbowmen and javelin throwers advanced at noon. The Flemish crossbowmen were the first to fire when the French archers came within range. The two sides were soon firing steadily at each other. The effect of the French crossbow fire on the Flemish main line was negligible.

When the French crossbowmen approached the streams, the fire became too hot for the outnumbered Flemish crossbowmen, and they fell back. The French crossbowmen halted when they reached the streams because to cross without support would have been suicidal.

Artois had grown impatient by that time, and at 1 pm he signaled his trumpeters to sound a general advance. The French cavalry had moved up behind the crossbowmen, so they didn’t have far to advance to reach the streams. Clermont’s wing was closer and was the first to reach the stream and begin to cross it. The knights advanced at a steady trot. They maintained tightly packed ranks with their stirrups nearly touching. They were clad in armor from head to toe.

When Clermont’s wing reached the Great Brook, the horses balked at having to ride into a water-filled stream twice the length of their bodies. Some of the horses would not jump the stream, and their riders had to force them to wade through it. The cavalrymen tried to get their mounts across the stream as quickly as possible so that they could reform and continue their attack. The vast majority of the mounted men were able to cross the stream and reform in a short span of time.

The Flemings stood shoulder to shoulder eight rows deep. In the front row of the Flemish line were pikemen alternated with men wielding goedendags. The pikemen had planted their 10-foot-long pikes in the ground at an angle and braced them with their feet to absorb the shock of the cavalry charge. The men armed with goedendags held them high to swing at any knight who should try to break through the formation.

Those knights with the greatest combat experience were able to get their mounts to plunge into the sharp hedge of pikes, but the horses of the majority of the attackers shied away at the wall of pikes. The Flemish soldiers wielding goedendags charged out after them and clubbed their horses in an effort to force the horses to dump their riders onto the ground. The mounted men who did penetrate the formation were quickly surrounded by groups of Flemish soldiers wielding goedendags. Whenever a French knight or squire was knocked to the ground, he was speared like a fish.

The knights of the two divisions on the far left of Clermont’s wing, which were led by Burlats and Brabant, had scant success against the men of Bruges. Nevertheless, some limited success was achieved by Brabant himself. Spying Jülich’s banner, Brabant steered his destrier toward the young prince. Brabant rode with such force toward his objective that his horse knocked Jülich down and toppled his banner as well. The Bruges men fighting with Jülich swarmed around Brabant’s horse, pulled the lord from his saddle, and stabbed him repeatedly.

Jülich continued fighting after being knocked down by Brabant, but his face had been cut badly. After a short time, several men escorted him to the rear. Fearing that the Bruges Corps would panic if word was incorrectly spread that the count had been killed in battle, his servant Jan Vlaminc donned his master’s coat of arms and joined the melee.

Since the center of the Flemish line was further from the two streams than the Flemish flanks, the two divisions of Clermont’s cavalry that struck the right flank of the Bruges Franc Corps were able to gain more momentum when they renewed their charge after crossing the stream. The attack by part of Clermont’s wing against the Bruges Franc was led by Clermont’s brother, Guy de Nesle, and Mathieu de Trie, both of whom held the rank of marshal. The marshals’ charge penetrated deeply into the Bruges Franc Corps, breaking the morale of some of the Flemish who fled toward the town.

For reasons not completely clear, the attack of Artois’ wing did not go forward until about 2 pm. Only three of the four divisions on the right wing went forward as Artois held back his division. Many of the knights had spent their entire lives preparing for bloody clashes such as the one that awaited them that day. They surged toward the Groeninge Brook, crossed it, and reformed on the other side. The men of the East Flanders Corps on the right of the Flemish line braced for the attack.

The veteran commanders of the French right wing included Jacques de St. Pol, Count Jean I d’Aumale, and Count John II d’Eu. The men under St. Pol and Aumale struck the East Flanders Corps, while Eu led his knights against the already disrupted Bruges Franc Corps. The French cavalry on the far right sought to reach Guy of Namur’s banner but had great trouble penetrating the hedge of pikes pointed skyward. French cavalry managed to penetrate to the location of the banner of Ghent, which was held aloft by a stout-hearted soldier named Zeger Lonke, and knocked him to the ground. Lonke made it back to his feet and waved the banner, which aided in rallying the Ghent contingent. The small number of knights and squires who penetrated the East Flanders Corps were quickly surrounded, unhorsed, and slain without mercy.

In the center, the Bruges Franc Corps, which had been partially disrupted by the charge of the French left wing, did not present a strong front in the presence of another strong mounted attack. The attack of Eu’s division against the left flank of the Bruges Corps benefitted from the success the French marshals already enjoyed against the right flank of the Bruges Franc Corps.

From the castle ramparts, the Viscount of Lens watched intently as the French attack achieved substantial success in the center. At about 2:30 pm, he ordered his troops to sally forth from the castle and attack the Flemish center from the rear. French crossbowmen on the castle ramparts fired down on the men of Ypres who were charged with preventing the garrison from joining the main battle. The commander of the Ypres contingent had placed his own crossbowmen in strong positions behind pavises, and they were able to cut down many of the French troops that charged out of the entrance of the castle. The few mounted men from the garrison were quickly surrounded by goedendag-wielding Flemish infantry and slain. The men of the garrison were greatly outnumbered. They never made it to their objective.

Renesse had observed large numbers of men from the Bruges Franc fleeing to the rear but felt it was not his place to rush forward and try to rally them. Rather, he was scanning the battlefield for the right moment to commit his reserve force to the fray. Once the veteran commander had determined that the enemy had committed the bulk of its troops to the battle, he decided the moment had come to put his reserve where it was most needed. Renesse ordered trumpets sounded to signal an advance, and he directed his fresh troops to the center so that they could assist the small number of brave men from the Bruges Franc who had not lost heart and were still fighting the enemy with great determination.

Renesse’s men rushed to wherever the French knights were getting the best of the Bruges Franc troops and joined the melee. French knights and squires who had up until then survived numerous attempts to knock or grab them from their saddles were overwhelmed by the reinforced Bruges Franc Corps.

By 3:30 pm, the Flemish infantry had nearly eradicated all of the cavalrymen who had penetrated their formation. And because of the commitment of the Flemish reserve under Renesse there was no danger from that point of the Flemish being driven from the field. The French cavalrymen who were still fighting the Flemish were falling back across the entire front toward the streams.

When the French horsemen began falling back, groups of Flemish troops began chasing after them, hoping to overtake them before they could escape. The distance to the streams was shorter on both flanks, and that is where the Flemish first fell on the French, who had the difficult task of coaxing their horses back across the barrier. Some of the horsemen successfully managed to jump their horses across the stream, but others tried to ride their horses through the stream. These cavalrymen were overtaken and killed by Flemish soldiers bent on revenge.

In the center, a few of the most experienced knights tried to reform to charge again into the Flemish ranks, but they were unable to separate themselves long enough from the pursuing Flemish to reform. In minutes they realized the futility of trying to reform and tried to escape. By that time the fighting was located along the stream banks as the Flemish clubbed and stabbed the French cavalry. Soon the stream bank was blanketed with dead and dying Frenchmen, and in many places the stream ran red with their blood.

Artois was stunned by the repulse of his seemingly impregnable cavalry by militia. He had been entrusted by Philip with vanquishing the rebel army, and he must have realized at that point that he had failed his sovereign lord. He had several hundred knights with him, and he decided to order them to charge at Namur’s position in the hope that he could disrupt the Flemish by slaying the man who had been partly responsible for the destruction of his army.

French trumpets signaled a fresh advance. Artois and those troops with whom he shared the greatest bond charged in a tight formation toward the Groeninge Brook. When he reached the Groeninge Brook, Artois shouted, “Let those who are faithful follow!” Then, with a magnificent leap, Artois’ horse cleared the stream. One advantage Artois and his men benefitted from was that the Flemish were no longer in a tight body, but instead were scattered in clumps around the battlefield. Artois and his men took advantage of this to steer around some of the groups along the stream and head for Namur’s position.

The Flemish troops hurriedly tried to close ranks when they saw not only the charge of Artois’ division but also the French rear guard walking their horses closer to the junction of the two streams in the center of the battlefield. Artois rode directly for Namur. The young prince and his bodyguards braced for the attack by the count, whose coat of arms bearing gold fleur-de-lis and castles against an azure background testified to his noble birth.

Artois reached the prince’s banner, and being mounted he was able to reach above the man who held the banner and grab hold of it near the top. He managed to tear the banner but had to let it go to fight the prince’s bodyguards. Realizing he was surrounded, the count fought with redoubled fury. By that time, Artois had discarded his lance, and he wheeled in circles on his horse slashing at his attackers with his sword.

Namur wanted the count taken alive, but the Flemish prince knew that it would be nearly impossible given the rage of the Flemish soldiers. Artois fought bravely and broke out of the encirclement several times until a particularly strong soldier, William van Saaftinge, clubbed Artois’ horse, sending it to the ground along with its rider. In their rage, the Flemish stabbed Artois as many as 30 times.

Despite having repulsed the main charge of the cavalry, as well as the follow-on attack by Artois’ cavalry division, fear spread like a fire on a thatched roof through the Flemish ranks when they saw the large French rear guard advancing in what they believed was a preparation for an all-out charge. For this reason, some of the Flemish began to fall back from the stream bank. Namur and the other knights in the Flemish ranks began to rally the wavering troops. At that moment, the men of Ypres, who had checked the attack of the castle garrison, joined the main army.

But there was to be no final charge by the French. The co-commanders of the reserve, St. Pol and Boulogne, had seen the Flemish steadily feeding fresh troops into the battle, and they believed that if the bulk of the army had not been able to defeat the Flemish neither would their two divisions. While this was a sound decision, the commanders of the reserve also chose not to try to extract the survivors, some of whom were still on the far bank and desperately outnumbered. It was a cowardly act but may have been a wise one since the Flemish could easily wade through the stream and engage the reserve in an effort to prevent it from safely withdrawing.

When they saw the French rear guard hesitate, the Flemish infantry began cheering, and their front ranks surged across the stream. In response, the commanders of the French rear guard signaled to the remaining troops to retreat. The French reserve was in such haste to leave that it abandoned valuable baggage in its camp to the Flemish. Some of the surviving Brabantine knights along the Great Brook, who had been unhorsed and were stumbling about, tried to pretend that they had been fighting in the Flemish army. However, one of the distinctions between the Brabantine knights and Flemish knights was that the former still had on their spurs, whereas the small number of Flemish knights had removed their spurs to fight on foot as instructed by Namur.

Namur was furious when informed of the deception, and he ordered all slain who had on gold spurs. Once this grisly task was completed, the Flemish proceeded to strip the bodies of the slain French of their gold spurs. Some of the Flemish then went to sack the enemy camp, while others marched in pursuit of the fleeing French, who were trying to reach French-controlled towns of Lille and Tournai.

The 2,000 French casualties of the battle included not only the commander-in-chief, but also the constable of France, one of the marshals of France, and most of the division commanders. The other French marshal, de Trie, was taken prisoner so that he could be ransomed for a large sum of money. The Flemish took pairs of gold spurs from 250 dead knights, and these were mounted as trophies in Courtrai’s Church of Our Lady.

The defeat of the most experienced, best equipped warriors in France by militia troops shocked the nobility of Europe. Fourteenth-century chroniclers considered the Battle of Courtrai to be an event of the utmost significance and likened the Flemish victory to some of the greatest military triumphs since recorded history began, including the Siege of Troy and the Battle of Carthage. The war between France and Flanders would drag on for three more years.

On June 23, 1305, Philip signed the Treaty of Athis-sur-Orge with Count Robert III of Flanders. The treaty stipulated that in exchange for conceding several French-speaking towns in western Flanders to the French, including Douai, Lille, and Orchies, Flanders could maintain its prewar status as a fief of France rather than being annexed by France.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments