By George Tipton Wilson

Ignoring a nonaggression pact between Hitler and Stalin, Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa, an invasion of the Soviet Union, on June 22, 1941. The Soviet Air Force was caught on the ground and nearly annihilated.

By November the German Army had fought its way to within 19 miles of Moscow. Leningrad was under siege. Three million Russians had been taken prisoner. A large part of the Red Army had been wiped out.

Immediately after the devastating attack began, the Soviet Union formed three regiments of female combatants at the behest of Marina Raskova, the Amelia Earhart of the Soviet Union. Raskova, already a heroine in aviation circles, had the ear of Soviet Premier Josef Stalin and convinced the wily dictator that women needed to be involved in the desperate fight.

It was a decision that many historians are convinced helped turn the tide of the war. By the close of World War II, nearly 1,000 Russian women had flown combat in every type of Soviet aircraft. Their participation has been called the best kept Russian secret of World War II. Even before the war, the Soviet government had encouraged women to participate in activities that earlier had only been the province of men. Women were to be the equal of their male counterparts in everything from being deck hands to flying airplanes.

One-Third of Soviet Pilots

As a result, women in the Soviet Union who wanted to learn to fly or work with airplanes were not discouraged or frozen out the way they were in America and to a lesser extent in Europe. The United States had its Jacqueline Cochran, its Nancy Harkness Love, its Amelia Earhart, and its Phoebe Omlie, but their fame was mainly relegated to “powderpuff derbies.” In the Soviet Union, it was not “healthy” to discriminate openly. Thus, by 1940, fully one-third of the trained pilots in the Soviet Union were women, and the Russian women pilots had set more flight records than the women of any other country.

One of the records was set on a nonstop flight from Moscow to the Manchurian border made in September 1938 by three women—Valentina Grizoduboya, Captain Polina Osipenko, and Lieutenant Marina Raskova—who were destined to take a leadership role in bringing women into aerial combat in the war against the Nazis. Raskova was the publicly acclaimed heroine among heroines because she selflessly parachuted from the plane during the last stages of the flight in a blinding snowstorm to lighten the plane’s load and assure a record-setting, nonstop distance. The aircraft subsequently crash-landed in a swamp near the border, and Raskova had to wander several days without food before she was able to rejoin her colleagues.

The three record-setting women were lionized throughout Russia, but Raskova’s fame far outlasted that of the other two. At the time of the flight, she was the navigator, but she went on to train and achieve excellent marks as a pilot. Her fame enabled her to grow close to Stalin, a position that could be tenuous at times, but one that augured well for the author of any project receiving his blessing.

Eleven months after the flight, in August 1939, an unthinkable diplomatic event occurred. Hitler and Stalin signed the non-aggression pact and became co-conspirators in the partition of Poland. Hitler subsequently stabbed Stalin in the back and launched the brutal, surprise attack on Russia in June 1941.

It was then that Martina Raskova joined the throng of would-be bureaucrats imploring the government to implement their plan to save the nation. With her connection to Stalin and the nation’s desperate need for military air personnel of all skills, it was a simple matter to get approval for women to join the Air Force and actively fight the German invaders. In fact, a few women pilots already were flying in the service, but they were highly dispersed and hardly visible to the general public. When Raskova called for volunteers to serve in all-women flying units in the summer of 1941, literally thousands responded. Distaff pilots, navigators, even mechanics rushed to lend their skills to help repel the invaders.

Training the “Summer Patriots”

By October, Raskova had personally interviewed them all and winnowed out the “Summer Patriots.” As the successful applicants were approved, they were billeted around Moscow. Finally, on October 15, the women of the 122nd Composite Air Group left for the training camp at Engles, a small town on the Volga River just a few hundred miles northeast of Stalingrad. There they received the same instruction and training given to all Soviet air units.

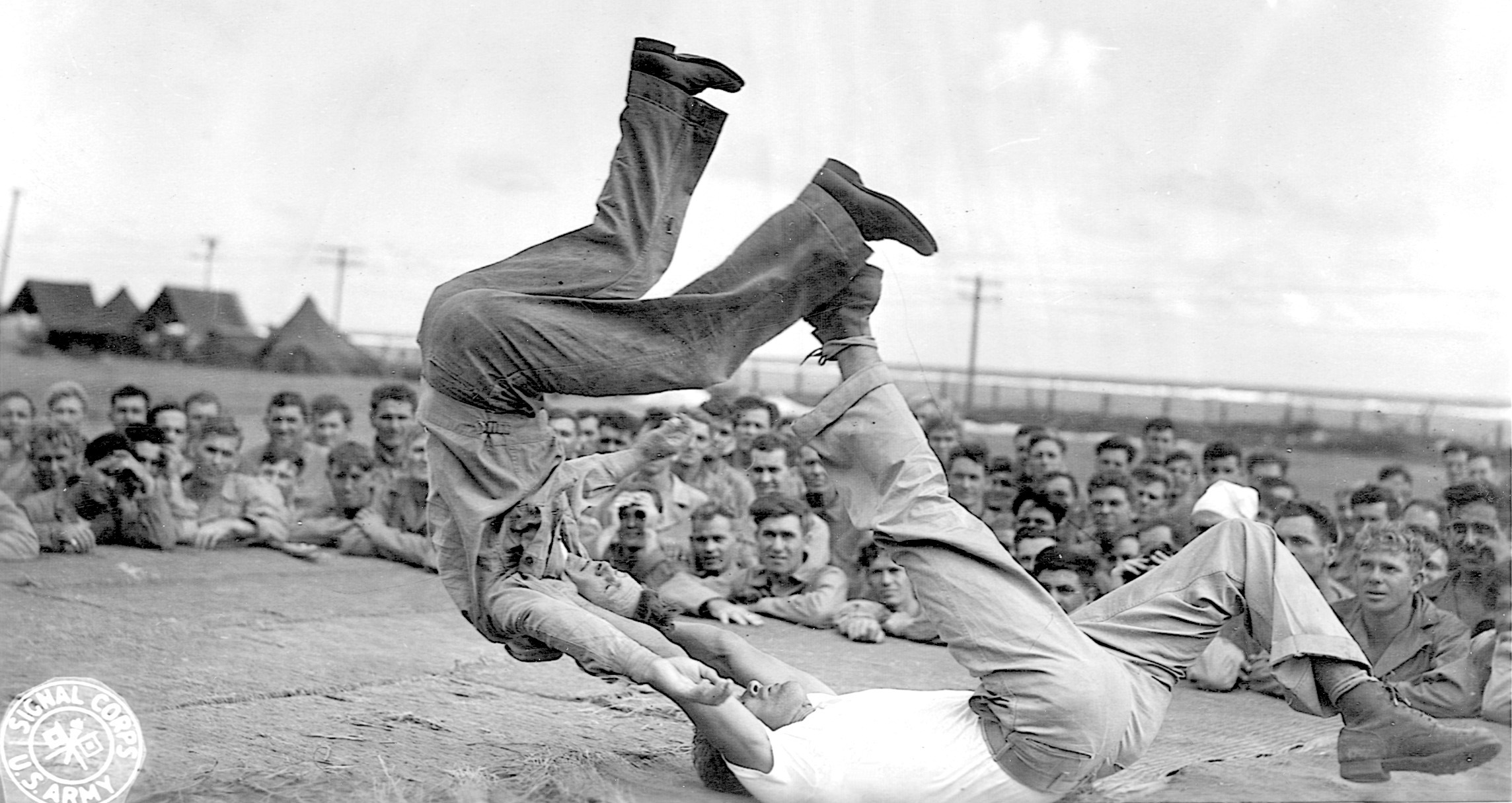

Shortly after the women arrived, they were reformed into three regiments, the 586th, the 587th, and the 588th Air Regiments. Nothing in the Russian records indicates these units were treated differently in any way, and the Soviet Army Air Force History of World War II accords them the same treatment as any Soviet Air Regiment. Training days were long and intense, lasting 14 to 16 hours. Much of the time was spent flying—on-the-job training for pilots and navigators. Ground mechanics worked equally hard to keep the training planes flying. Instant recognition of all types of German planes was a primary classroom subject. But the body of knowledge that was so important to each recruit was so huge and the time to master it so short that the women were constantly pressed. Yet they persevered.

The 856th Fighter Regiment was the first to end training and move into combat. Its commander was Major Tamara Kazarinova. Unfortunately, her health failed soon after the regiment moved into its operational headquarters at Saratove. She was replaced by a man, Lt. Col. A.V. Gridnev, who commanded the regiment until the end of the war. The regiment flew the Yak-l, a Soviet fighter designed by the Yakovlev Bureau and comparable the German Messerschmitt and British Spitfire. The unit was used primarily to guard specific targets, fending off German bombing and strafing sorties. Since its mission was defense, it did not rack up huge numbers of kills, but was equal to every assigned task.

Two Women Fighter Aces: Lilya Litvyak and Katya Budanova

Eight of the regiment’s exceptionally skilled pilots transferred to a previously all-male regiment in September 1941. Instead of defense, this regiment was employed in seeking and destroying German planes anywhere in its operational area. As a result, two of the women, Lilya Litvyak and Katya Budanova, earned the right to the coveted title of “ace” while flying as “Lone Wolf” fighters. Litvyak had 12 kills and three partials, while Budanova was reputed to have more, although no reliable record seems to exist.

Litvyak’s life as a Soviet pilot was the stuff of which movies are made. Apparently, she possessed the necessary physical and mental skills a successful pilot has always required, whether in the early days of aviation or in today’s supersonic jets—exceptional hand-eye coordination, marvelously quick reflexes, keen intellect, lightning-fast decision-making capacity, and indomitable courage. She was a shy, retiring, curvaceous blonde beauty out of the cockpit; in it she was a roaring exhibitionist.

Lilya’s daredevil moves were the envy of every pilot with whom she came into contact. If the pilot was a man, he promptly fell in love with her. As word of her feats spread through the Red Air Force, her ability to execute others more numerous and daring seemed to grow also. She survived two serious wounds in combat and each time returned to her relentless pursuit of the German invaders much too soon for her own good health. But Lilya was eternally sanguine about her capacity as a fighter pilot. Many of her peers had already included her in the international ranks of legendary pilots.

The mechanic who serviced Lilya’s aircraft, Sergeant Inna Pasportnikova, decribed Lilya’s insouciant ways to Anne Noggle, whose book A Dance with Death is the definitive work on women’s contribution to the Soviet Air Force in World War II. “When Lilya approached the airdrome after a victory, it was impossible to watch her; she would fly at a very low altitude and start doing acrobatics over the field. Her regimental commander would say, ‘I will destroy her for what she is doing. I will teach her a lesson!’ After she landed and taxied over to our position, she would ask me, ‘Did our father shout at me?’ And he had shouted at her, and then he admired what she had done.

“She flew so low over the field covers of the aircraft would flap and fly around, she created such a wind! When she was shot down the first time, she received a new Yak-1. Men tried to stop her from flying because they wanted to save her, but it was impossible.”

Finding Lilya Litvak

Lilya’s vibrant personality went well with her blonde hair and fair features. The whole package was a young man’s dream, and plenty of Soviet airmen of that day dreamed of wooing and winning her. However, she fell for only one. He was Alexei Salamon, her squadron commander. Their romance lit up the sky almost as brightly as their aerobatics between September 1942 and May 1943. Then, on a beautiful, late spring day, Alexei was in the sky flying a routine training session, showing a recruit how to perform aerobatics. His plane malfunctioned, and he was killed in the ensuing crash.

The accident was almost more than Lilya could bear. Not only was her lover Alexei dead, but the crack pilot died in a mundane accident that had nothing to do with his ability as a pilot. The irony seemed to goad Lilya into more furious aerial activities. She flew relentlessly, spending almost every waking moment in the air.

About three months after Alexei’s tragic accident, Lilya and her wingman ran afoul of German fighters while escorting bombers on a mission. The date was August 1, 1943, and it marked the end of Lilya’s aerial panegyrics. She crash-landed her plane near a village and was apparently killed by the impact. However, her body was not found in the wreckage. Her commander pressed hard to have her awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union, but the authorities refused because no trace of her body could be found. They speculated that she might have been captured by the Germans. The mystery was added to the Litvyak legacy of skill and daring, and the puzzle remained unsolved for many years.

Inna Pasportnikova told how she, her husband, and grandchildren searched for the remains of Lilya’s body for more than three years. They used metal detectors over an extensive area in the vicinity of the crash site but found no trace of it. For decades, rumors of Lilya sightings popped up across the Soviet Union. There were even comments about the gross exaggeration of her death, but Lilya never showed up in the flesh.

Finally, in the late 1980s, two boys playing in a field in Belorussia started enlarging a hole that they had seen a snake enter. They did not find the snake, but they did uncover some human bones. After extensive investigation and evaluation by forensic experts, the mystery of Lilya Litvak’s demise was solved. Apparently, the inhabitants of the nearby village had buried her immediately after her crash to deny the Germans any opportunity of desecrating her remains.

The year 1990 saw the end of the long, winding Lilya Litvyka trail. President Mikhail Gorbachev proclaimed her posthumously a Hero of the Soviet Union. Although official recognition of her skill and daring was 47 years in coming, the inspiration Lilya provided her peers in the Red Air Force was a palpable factor in molding the airwomen into effective defenders of their country.

The “Night Witches” and their PO-2s

The origin of the sobriquet “Night Witches” (the Nazi term was Nachthexen) lay with the 588th Air Regiment. It was the only one of the three to remain under the control of a woman, Major Yedokia Bershanskaya, throughout the war. Its objective was twofold. First, of course, was the destruction of German military installations, but it also extracted a growing psychological toll on German soldiers as the struggle continued. The “pop, pop, pop” of the engines in the Polikarpov PO-2 aircraft they flew was so distinctive that when German troops heard them, they automatically began to dive for cover from bombs, conditioned to jump at the sound.

Since the regiment’s pilots flew virtually all night long every night, it is easy to imagine the emotional trauma they wreaked on the tiring German soldiers. MacBeth’s witches chanted, “Hover through the fog and filthy air.” Perhaps the ranks of the Wehrmacht that surrounded Stalingrad contained a Shakespearean scholar or two who remembered that line, and thus thought it appropriate to dub their tormenting Russian women Night Witches. In any event, the nickname stuck, and soon spread to all Russian airwomen.

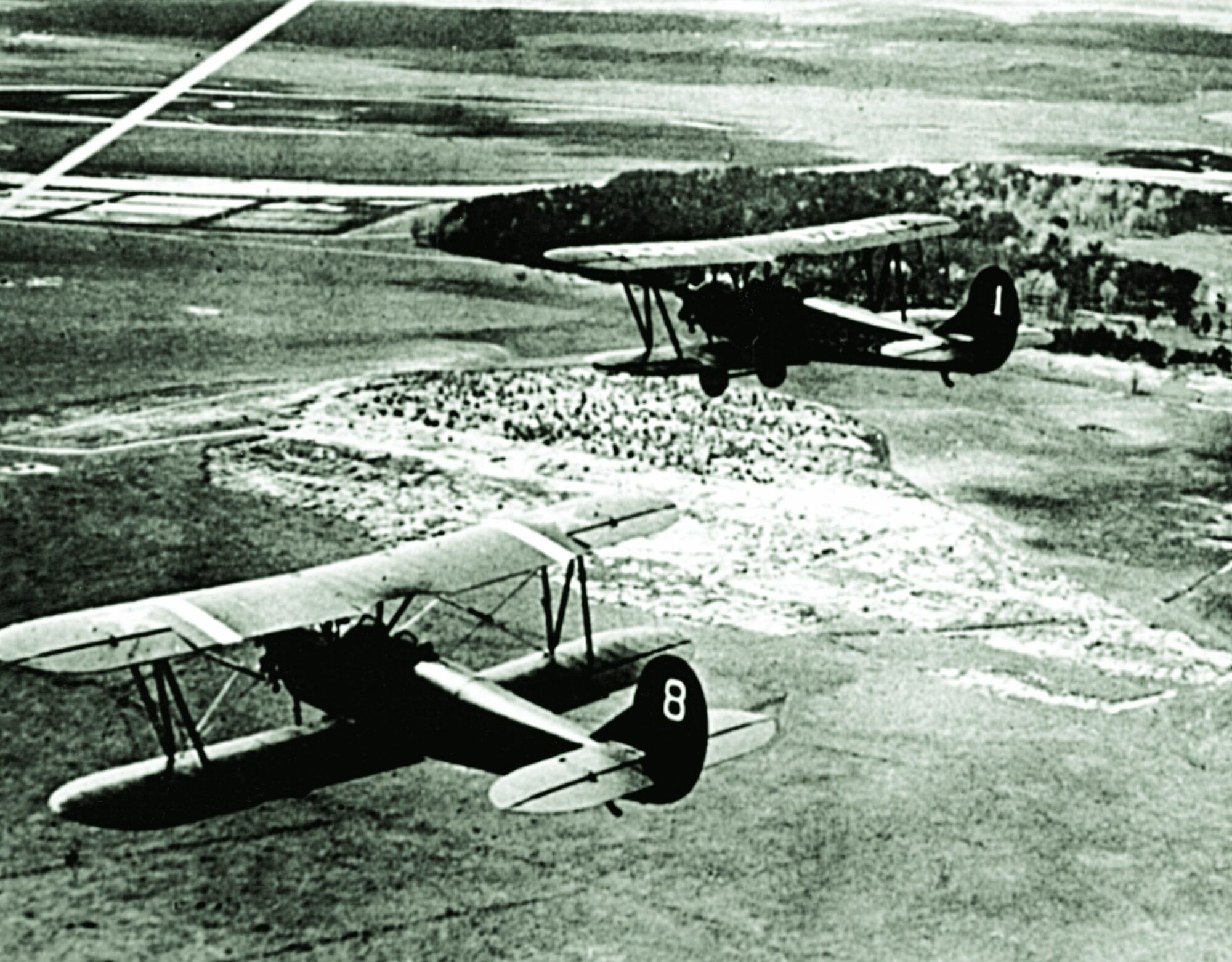

The PO-2 was virtually a flying anachronism. It was designed in 1927, but new production had almost ceased by 1941. It was made of wood and covered with fabric, hardly cutting- edge technology even for 1941. Presumably, even the lethargic Soviet production facilities could be counted on to make them quickly and in sufficient quantity to be hustled into the breach against Germany.

The cockpit of the plane was open, and its cruising speed was an agonizingly slow 60 miles per hour. The slightest brush with antiaircraft fire or tracer bullets set the aircraft ablaze. The crews were not even provided with parachutes until 1944. So, for three years every mission was fraught with great peril.

Primeval living conditions, primitive equipment, long hours on duty without sleep, and abject danger were bad enough, but the women often were subject to the political stresses placed on Soviet citizens during those times. Lieutenant Mariya Tepikina-Popova told of her experience in joining the regiment: “While I was being interviewed at headquarters a personnel officer saw my last name and asked if I was related to the political officer of the same name, who was assigned to the same training school where I had been a pilot.

“I knew this officer with the same name had been arrested and imprisoned as an enemy of the republic in 1937. I thought quickly how I would best answer, because I was not related to him. In these times you had to deny any knowledge of him, or the consequences could be quite unpredictable and include prison. So I answered that I kept my distance from the command and staff of the school and didn’t know him. The personnel officer understood my evasion and replied, ‘Oh, since he was my best friend and you are a Tepikina too, I’ll let you join the 46th Regiment.’”

24,000 Combat Missions, 1,100 Nights

During the war, the regiment flew 1,100 nights of combat, just about every single night from the time it entered combat in 1941 to the end of the war in 1945. It flew 24,000 combat missions. Twenty-three of its women were recognized as Heroes of the Soviet Union, five posthumously. The unit was designated an elite or “Guards Regiment” in 1943 and thereafter was known as the 46th Tamar Guards Bomber Regiment. It fought in the Caucasus, Crimea, and Belorussia.

The 587th Bomber Regiment was the third unit to be formed from of Marina Raskova’s 122nd Composite Air Group. Instead of the antiquated PO-2, it flew the Petlyakov PE-2. This was a modern twin-engine dive-bomber with a maximum speed of more than 330 miles per hour. With its twin fuselage configuration, it was one of the Red Air Force’s most difficult planes to fly and was just coming into production in the spring of 1942.

Thus, while the other two regiments were training in the planes they would fly in combat, the 587th could only work in classroom training, using service manuals and other instructive material. Finally, the PE-2s began to arrive at Engles in late August and early September 1942. Training consumed the rest of the year, and in January Raskova led her unit to an airfield on the Volga River near Stalingrad.

Then fate struck Marina Raskova a cruel blow. She, whose aerial career had been fawned on by fortune for years, suddenly saw her good luck spin out of control. On a routine flight to the regiment’s new base, bad weather struck. As she flew closer to the base, the weather grew worse. When she tried to land, her plane crashed into an embankment on the other side of the river. She and her crew were killed instantly. Marina Raskova had never flown a combat mission.

However, her regiment certainly did. The first combat mission of the 587th was in February 1943, and the regiment was under the command of a man, Major Valentin Markov. He maintained command of the unit throughout the remainder of the war, despite his initial skepticism about female pilots flying combat missions. As he expressed it in a 1992 interview, “I couldn’t visualize how I could command women during war, flying bombers. I knew the aircraft and knew how difficult it was even for men to fly. I didn’t know how women could manage it.”

The skepticism was mutual. A navigator, Captain Valentina Kravcheno, spoke for the entire regiment when she said, “We wouldn’t even hear of a man coming to command our regiment.”

Discipline and devotion to duty won out, and the regiment served with distinction. In the fall of 1943, it was honored with the designation of a Guards Regiment and was renamed the 125th Guards Bomber Regiment.

“Almost All of Them Were Shot Down”

Markov ended his career as a lieutenant general in the Soviet Air Force. During the 1992 interview, he went on to elaborate on the complete metamorphosis of his views on women pilots flying in combat. “It’s hard to fancy how difficult the conditions were for these women,” he reflected. “Almost all of them were shot down and, after hospitalization, they came back and flew bravely.

“The women in my regiment were self-disciplined, careful and obedient to orders; they respected the truth and fair treatment to them. They never complained and were very courageous. If I compare my experience of commanding the male and female regiments to some extent at the end of the war, it was easier to command this female regiment. They had the strong spirit of a collective unit.”

Between 1943 and the war’s end, the 125th Guards Bomber Regiment moved its operations as the front moved westward through Belorussia, the Baltic area and eastern Prussia; it was based in German territory when the Third Reich surrendered. Its members flew up to three sorties a day, dropping 980,000 kilograms of bombs, attacking enemy positions, and harassing troop concentrations. Five of its pilots were named Hero of the Soviet Union. In contrast, 23 of the 46th Regiment’s flyers received that award.

Of that disparity Markov commented, “From the present viewpoint I can see that very few of my girls were awarded the highest title. If I could turn time back, I would have promoted more of them for that award. Now I have a grave sentiment about that, because many of them deserved it.”

By the end of World War II as many as 18 percent of the personnel in the Red Air Force were women. Even before Marina Raskova’s legendary call for female volunteers in 1941, women were serving in various parts of the Red Air Force. Her organization of the three women’s regiments and their outstanding performance lured even more women to serve. They came asking only to serve the country they loved. Month after month they faced tremendous danger. They endured the harsh demands of combat service, survived disasters and life-threatening sorties, and suffered sickness and wounds. Yet they always remained to perform their duties in service to their country.

Socrates explained to Crito about his obligation to obey the call of the state: “This is the voice I hear in my ears, like the sound of the flute in the ears of the mystic. Its humming prevents me from hearing any other.” That same voice must have hummed in the ears of those heroic women whom the Nazis disdainfully called Night Witches, but in the end contributed so much to toppling the Nazi dictator who had envisioned conquering the Soviet Union.

George Tipton Wilson is a resident of Memphis, Tennessee. A veteran of World War II, he received the highest possible intelligence clearance while working as a cryptographer at the Pentagon and on the staff of General Douglas MacArthur in Australia.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments