By Christopher G. Marquis

In the late summer of 1813, some 550 men, women, and children took refuge within a small wilderness outpost and waited for the worst. The stockade surrounding the house and sheds of Samuel Mims lay roughly 30 miles north of Mobile in Mississippi Territory (comprising the modern states of Mississippi and Alabama). Following months of attacks and reprisals between the Creek Indians and white settlers, many civilians decided to seek safety in numbers, bringing their families and slaves to the apparent security of Fort Mims. They were joined by a few friendly Indians.

Major Daniel Beasley, ordered by Governor William Claiborne of Louisiana to defend the settlers, arrived at the fort with 175 militiamen. After several days of relative inaction, complacency set in. The gates remained open, and the occupants went about their daily routines. When a slave reported having seen the approach of Creek warriors, Beasley had him flogged for spreading rumors.

The following day, August 30, a sharp war cry arose from outside the gates. A thousand Creek Indians, or “Red Sticks” as they were called for their crimson-painted war clubs, descended on the fort. Beasley was among the first killed, tomahawked as he attempted to close the gate. His subordinate, Captain Dixon Bailey, rallied his men for a spirited defense inside the buildings. They resisted until 3 pm, when a Red Stick chief, Red Eagle, rode up to the fort on a black horse. He ordered his warriors to set fire to the structures and drive out the resisters.

A terrible slaughter ensued. The Red Sticks made no distinction between combatants and noncombatants. Red Eagle tried to spare the women and children, but his warriors were beyond his control. When a rescue party arrived at Fort Mims 10 days later, they found a grotesque scene. About 400 corpses of men, women, and children had been scalped and abandoned to the dogs. The survivors consisted of about a dozen militiamen who had managed to escape and some less fortunate blacks who were seized by the Red Sticks and kept as slaves. Bailey had somehow fought his way out of the fort, but he soon bled to death from his wounds.

The War of 1812 in the West

News of the massacre spread terror and outrage throughout the western and southern states, but for President James Madison it was just another disaster in the never-ending nightmare of the War of 1812. Madison had signed the war declaration against Great Britain on June 18, 1812. The reasons given for the war primarily involved outrages committed by the Royal Navy against American vessels (including the impressment of civilian sailors), as well as British incitement of Indian tribes against American settlers. Even so, the war vote was very close—four switched votes in the Senate could have stopped it—and the nation was far from united in favor of hostilities.

The leading political advocates for war, the War Hawks, hoped to use the conflict as an excuse to quickly invade and annex Canada while the British were busy battling Napoleon’s armies in Spain and blockading European ports with their massive navy. The War Hawks’ schemes quickly went awry. The three-pronged attack on Canada, designed by General Henry Dearborn, turned into a threefold disaster. In August, Brig. Gen. William Hull surrendered Detroit to the British. On the Niagara frontier, 300 Americans were killed or wounded, and another 950 were taken prisoner at the Battle of Queenston Heights. The small American Navy did manage to score a handful of victories over the vaunted Royal Navy, but these were exceptions to the seemingly irreversible trend of humiliations and defeats.

The British were not the Americans’ only problem. The extraordinary Shawnee Indian chief, Tecumseh, had worked for years to assemble an alliance of Indian tribes to halt white encroachments on native land. In October 1811, he traveled south into Creek country, where he delivered an incendiary talk. “They seize your lands,” he told the tribesmen. “They corrupt your women. They trample on the ashes of your dead. Back, whence they came, upon a trail of blood they must be driven. Back! Back! Ay, into the great water whose accursed waves brought them to our shores! Burn their dwellings! Destroy their stock! Slay their wives and children! The Red Man owns the country. War now! War forever! War upon the living! War upon the dead! Dig their very corpses from the grave. Our country must give no rest to the white man’s bones.”

Tecumseh and his followers, seizing upon the War of 1812 as a golden opportunity to thwart the Americans, became valuable allies to the British. They ambushed the Americans withdrawing from Fort Dearborn, killing most of the 93 soldiers. On January 21, 1813, they again surprised a large American contingent at the Raisin River, killing almost 300 troopers. On June 23, 1813, 575 cavalry and infantry were surrounded by a smaller force of Caughnowaga and Mohawk Indians and forced to surrender at the Battle of Beaver Dams. The mere threat of Indian attack had caused Hull to surrender his 2,000-man garrison at Detroit.

Among those won over by Tecumseh’s passion was Chief Red Eagle. Born William Weatherford, Red Eagle could claim only one-eighth Indian blood. His great-grandmother was a member of the legendary Creek “Clan of the Wind.” Otherwise he was of French, English, and Scottish descent. Ironically, his white adversaries Samuel Mims and Daniel Beasley each had more Indian blood than he did. In 1813, Red Eagle was 33, with a tall, straight frame and piercing eyes. He had lived among both the whites and the Indians, and he had chosen to tie his fate to the latter. The more peaceable Creeks saw him as an interloper and a threat, but he commanded a majority of their warriors, 4,000 Red Sticks.

“Old Hickory” Andrew Jackson

In Tennessee, the massacre at Fort Mims enraged and galvanized the citizenry. On September 25, 1813, the state legislature empowered Governor William Blount to recruit 3,500 volunteers to march into Creek country and destroy the threat. The perfect man to lead the offensive was widely known. Unfortunately, he was lying in bed at home just then, in agony over two gunshot wounds in his left arm. His name was Andrew Jackson.

This would not be Jackson’s first military campaign. He had set out at the head of his division the previous year to help head off a possible British landing on the Gulf of Mexico. On January 7, 1813, 1,400 Tennessee miltiamen had boarded flat-bottom boats to float down the Cumberland, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers to Natchez. Jackson’s 600-man cavalry was led overland by Colonel John Coffee.

Upon arriving in Natchez, Jackson had received a note ordering him to halt until further notice. The next month, the newly appointed secretary of war, John Armstrong, ordered him to dismiss his force and hand over his equipment to Brig. Gen. James Wilkinson, the military commander in New Orleans. Appalled at the thought of abandoning his division so far from home, Jackson instead marched the troops 800 miles back to Nashville. It was on this march that Jackson’s sheer willpower led his men to nickname him “Old Hickory” for his toughness. Upon reaching home, Jackson dismissed the troops and resumed life at his mansion, the Hermitage.

During this idle time, Jackson became involved in a dispute between Captain (later Colonel) William Carroll and Jesse Benton, brother of Lt. Col. Thomas Benton, Jackson’s aide-de-camp. Jackson attempted to arrange a reconciliation between the two parties, but failing that, he agreed to serve as Carroll’s second. In the duel, Benton shot Carroll in the thumb, while Carroll shot Benton in the buttocks. (While firing, Benton had contorted his body in such a way as to leave his backside vulnerable.)

Thomas Benton was outraged at his brother’s humiliation. He publicly denounced Jackson, and Jackson in turn vowed to horsewhip him. He saw his chance on September 4, when the Bentons were staying at the City Hotel in Nashville. Jackson was in town with Stockley Hays, his nephew. When he passed Thomas Benton standing in the doorway of the City Hotel, Jackson brandished a horsewhip and charged him. In the ensuing brawl, Jackson was seriously injured when Jesse Benton, hiding inside the hotel, shot him in the shoulder and upper left arm at point-blank range. Jackson almost lost the arm, but he ordered his doctors not to amputate.

Tennessee officials found Jackson in a debilitated state when they arrived to request his services for a new campaign against the hostile Creeks. Like many American military leaders of the time, Jackson had no formal military training and had attained his position through political ties. Unlike other commanders, however, he possessed an iron will that amazed friends and foes and compelled others to follow him against the most daunting challenges.

Lessons from Napoleon

Jackson’s strong determination contrasted with his comparatively fragile physique. In September 1813, he was 46 years old, six feet, one inch tall, and weighed 145 pounds. His face bore the scar of a British officer’s sword strike, received when Jackson was a 13-year-old prisoner of war and had refused to shine the Englishman’s boots. A bullet from another recent duel remained lodged in his chest, along with two broken ribs and an abscessed lung. His left arm was still in a sling when he rendezvoused with his division on October 7 at Fayetteville, Tennessee.

The strategy for the Creek War, drawn up by Maj. Gen. Thomas Pinckney, commander of the southern district, involved a three-pronged invasion. Militia and volunteers from Tennessee would move south, while militia from Georgia and regulars from Louisiana advanced on either side. The Tennessee forces were divided into two divisions. Maj. Gen. John Cocke was to lead his East Tennessee division down from Knoxville, while Jackson moved south from Middle Tennessee. When the two forces combined, Jackson would have seniority and take command.

Jackson’s division contained three brigades totaling 3,000 men. His brigade commanders were Brig. Gen. William Hall of the volunteer infantry, Brig. Gen. Isaac Roberts of the militia, and Colonel John Coffee of the cavalry. Among Jackson’s staff were Colonel William Carroll, of the infamous Benton duel; Major John Reid, Jackson’s personal aide; and Major William Lewis, the division quartermaster.

Recognizing the recent example of Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Russia, Jackson wanted to take all possible precautions regarding supplies. He obtained promises from private contractors that they would deliver regular shipments (10 wagonloads per day) to his intended base on the Coosa River. Even so, a winter campaign deep in the hostile wilderness was inherently risky.

Jackson’s Campaign Begins

Once in motion, Jackson’s army moved swiftly, marching first to Huntsville, then across the Tennessee River and southeast to Thompson’s Creek. There, the troops began to build Fort Deposit to serve as a depot for the expected supply train. Jackson then led his men over Raccoon and Lookout Mountains to the Coosa River. On November 1, he arrived at the Ten Islands, where he halted to construct his theater headquarters, Fort Strother.

The men of the army, like their commander, were hardy frontiersmen. They possessed a strong sense of fraternity and bravery, but also a streak of stubborn independence that, if left unchecked, could have a deleterious effect on military order and disciple. One of the young adventurers was a 27-year-old bear hunter named David Crockett, who had enlisted following the massacre at Fort Mims. Crockett had a deep personal investment in the campaign—his grandparents had been murdered by Creeks in their home several years before. Crockett rode in Coffee’s cavalry and was well-liked for his storytelling talent and charitable disposition.

Jackson dispatched Coffee’s brigade to subdue the Red Stick village of Tallussahatchee, 13 miles east of Fort Strother. A small force of Creek warriors, sent out to meet the invaders, fell into a trap set by Coffee and was obliged to retreat into the village. The cavalry surrounded the huts and was preparing to take prisoners when one of the women inside the village shot and killed a young Tennessean. This so enraged the men that they launched an all-out assault on the village. “We shot them like dogs,” Crockett recalled. A house occupied by 46 warriors was burned to the ground, and all the occupants inside died from flames, smoke, or bullets.

In the first battle of the Creek War since Fort Mims, 200 Red Sticks were killed and 84 women and children were taken prisoner. The Tennesseans lost five killed and 31 wounded. It was an auspicious beginning and suggested that the campaign would be short and easy. One of the survivors of the battle was a 10-month-old infant, found lying in the arms of his deceased mother. Back at camp, the baby was handed over to Jackson. Old Hickory attempted to give him to the Creek women for safekeeping, but they had no wish to raise the orphan. Having been orphaned himself at age 13, Jackson showed uncharacteristic compassion for the child. He fed the boy, named him Lyncoya, and sent him back to his wife, Rachel, at the Hermitage to be raised as their own.

A few days later, news arrived that a friendly Creek village, Talladega, was under siege by 1,000 Red Sticks. Jackson decided to lead the relief himself, leaving behind a small garrison to receive the anticipated supplies. At Talladega, Jackson’s force was double that of the Red Sticks. As Coffee had done at Tallussahatchee, Jackson encircled the enemy and then lured them into the trap with a weak feint.

The Red Sticks took the bait and soon found themselves in a veritable shooting gallery, surrounded by dead-shot frontiersmen on all sides. Seven hundred Creek warriors managed to fight their way out, but only after losing another 300 killed. The Tennesseans lost 15 killed and 85 wounded. It was another lopsided victory, but the elusive Red Sticks would live to fight another day.

Supply Problems of the Campaign

Disappointed, Jackson returned to Fort Strother to gather new provisions. It would be more than two months before the Tennesseans were able to launch another offensive. Upon returning to Fort Strother, Jackson discovered that the brigade that was supposed to be guarding the fort under Brig. Gen. James White had departed to rejoin Cocke’s division. The fort had remained undefended except for veterans recovering from wounds sustained at Tallussahatchee. More disturbing was the news that no supplies had arrived.

The contractors insisted that the rivers and streams in Tennessee were too low for the shipment of supplies. Jackson suspected the contractors were purposefully delaying delivery to increase their bargaining power. Whatever the reason, Jackson realized the seriousness of the situation. He ordered his private stores distributed among the men and the remaining cattle butchered, with the wounded receiving the first share of rations.

As November wore on and no supplies arrived, Jackson sent letters urging the contractors to deliver on their promises. “We have been starving for several days, and it will not do to continue so much longer,” he wrote. “Hire wagons and purchase supplies at any price rather than defeat the expedition.” Still, the promised supplies did not arrive. Order and disciple began to break down. Soldiers who would bravely charge a band of Red Sticks became dispirited by weeks of sparse rations. Even so, no one could claim that their commander did not suffer with them. When one private approached Jackson complaining of the lack of food, the general offered to share the contents of his own pockets and produced a handful of acorns.

Jackson’s Strategies of Command

Jackson held his command together through strength of will. One tactic he used was to play the different brigades against each other. One day, the militia determined to quit the campaign and march off as a unit. Jackson placed the volunteers in their way. The militia yielded and returned to their posts. The next day, the volunteers attempted to leave, and this time the militia stood in their way, happy to return the previous day’s favor. Even so, Jackson realized that the situation was becoming desperate. To avoid all-out mutiny, he promised the officers that if no supplies arrived in the next two days, he would lead the troops back to Fort Deposit.

On the appointed day, Jackson kept his word. Leaving 200 men to garrison Fort Strother, he commenced the march north. They had scarcely gone a dozen miles when they met one of the contractors, driving a herd of 150 cattle. Overjoyed, the army commenced to slaughter, cook and eat the cattle where they fell. Jackson was certain that the newly nourished soldiers would return to Fort Strother, but the troops were emboldened to give up the campaign and return to their homes. In spite of their officers’ pleas, the troops formed up to resume their march north. A lone figure on horseback stood in their way. Jackson, his left arm still in a sling, leveled a musket at the men, promising to shoot the first man who moved. No one did. Coffee and Reid joined their commander. Soon, a few loyal troops lined up behind them. After several tense minutes, the troops stood down and agreed to return to Fort Strother.

Jackson could not rely on other commanders to assist him. After Tallussahatchee and Talladega, the Red Sticks’ power seemed on the verge of collapse. One Creek tribe, the Hillibees, offered to make peace. Unfortunately, Cocke and his East Tennessee division were unaware of the offer. They attacked numerous Hillibee villages, killing 60 warriors and leaving their women and children homeless. The Hillibees understandably withdrew their peace proposal and threw their support to the Red Sticks.

The regular troops advancing from Louisiana moved too slowly to do much good. In one engagement, they had a chance to capture Red Eagle, but he leapt his magnificent black horse from a height of 80 feet into the Alabama River. He emerged from the river, still atop of his horse and grasping his rifle. Meanwhile, Georgia militia advancing from the east were checked by the Red Sticks at Autosee.

“I Will Perish First”

Back at Fort Strother, starvation was no longer a worry, but the limits of a volunteer army became all too evident. Most of Jackson’s volunteers had signed up for a one-year term of service on December 10, 1812. They considered December 10, 1813, the end of their obligation. Jackson interpreted the agreement to mean one year of active service. They had been inactive following the Natchez expedition until mustering again after the Fort Mims massacre. He dated their renewed service from then. The volunteers, convinced that their interpretation was correct, prepared to march out on the night of December 9. Jackson again placed himself in their way. This time, he enlisted the support of two artillery pieces. He implored the men to maintain the dignity they had earned, but he warned that he would fire on them if necessary. The officers consented to remain until they could reach a mutually agreeable solution.

This bought Jackson time, but he realized that he needed relief soon. Within a couple of days, Cocke arrived with his division, and Jackson dismissed the volunteers, who returned to Tennessee with bitter tales of Old Hickory’s heavy-handed leadership. Shortly after their departure, Cocke informed Jackson that most of his troops had only 10 days left in their terms of service. Battling his rage, Jackson ordered Cocke to return to Tennessee with his troops and recruit a new army immediately.

More bad news arrived. Coffee, who had left to acquire supplies for his horses, returned to Fort Strother to report that the cavalry had joined the dismissed volunteers and returned to Tennessee. The militia, whose commitment was not explicitly stated, insisted that a three-month term was the precedent for serving outside of their home state. This meant that January 4, 1814, would conclude their obligations. Jackson referred the matter to Governor Blount, hoping to keep the army from further disintegration. In the meantime, General Pinckney, unaware of any problems, urged Jackson to hold his position.

The volunteers and militia had strong reasons for wanting to return home. Being citizen soldiers, they had left behind families that needed to be fed, clothed, and protected against the numerous dangers of frontier life. As farmers, they had already made a great sacrifice of time to participate in the fighting. They feared ruin if they missed the upcoming planting season. At no time, however, did any of the near mutinies become violent, and only rarely did an individual desert.

Near the end of December, Jackson received the much-anticipated response from Blount. While the governor sided with Jackson in the matter, he believed that it was useless to hold the militia against its will. He advised Jackson to dismiss the militia and abandon the campaign until a new army could be raised. Jackson informed the militia of the governor’s decision, told them that it was their choice to stay or go, and implored them not to turn their backs on the campaign. To the general’s chagrin, the militia wasted no time in forming up and marching out of Fort Strother. As the new year commenced, the entire American army in the Creek campaign consisted of a single regiment.

Jackson would not return to Tennessee without victory. “I will perish first,” he wrote to Blount. “I will hold the posts I have established, until ordered to abandon them by the commanding general, or die in the struggle; long since have I determined not to seek the preservation of life at the sacrifice of reputation.” The remaining regiment was due for dismissal on January 14, 1814. Jackson’s attempts to play on their patriotism were largely unsuccessful. On the day of their scheduled departure, General Roberts and Colonel Carroll returned from Tennessee at the head of 800 new recruits. This sudden fluke of good fortune led Jackson to decide to renew the campaign while morale was still high.

Marching on Horseshoe Bend

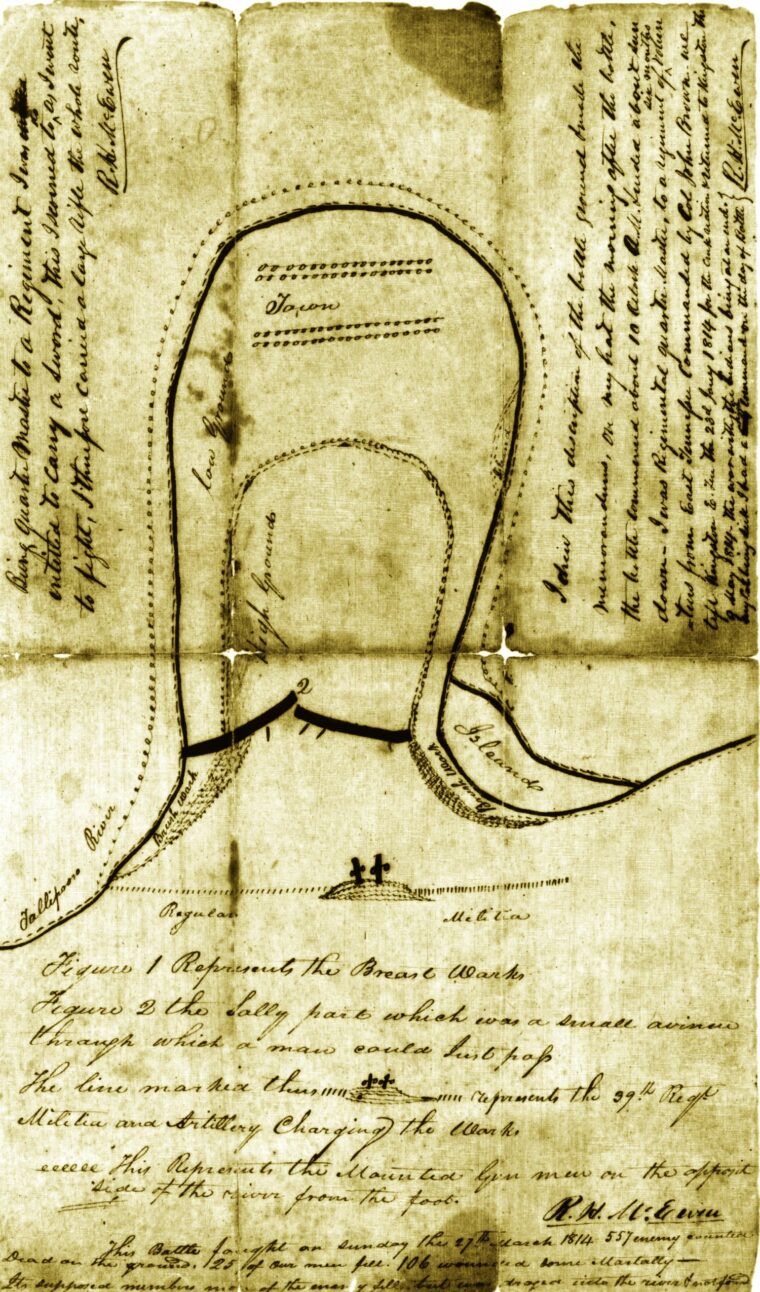

The new army advanced toward the capital of the Red Sticks, Tohopeka, also known as Horseshoe Bend. The village sat on about 100 acres of land within one of the bends of the Tallapoosa. The river provided a natural barrier on three sides, with a narrow “neck” on the northern side. Jackson’s army drew within three miles of the village before night fell. Spies informed Jackson that the Red Sticks knew of their approach and would attack soon. Before dawn on January 21, the Creeks charged Jackson’s left flank. The new recruits held the line and pushed them back.

The Red Sticks then attacked the right flank. Coffee, on the left, attempted to encircle the enemy, but the lack of discipline among the Tennesseans became evident. Only 53 men followed him. A Red Stick counterattack on the left threatened to encircle the men. Coffee was wounded and Major Alexander Donelson, Jackson’s brother-in-law, was killed. Two hundred Indian allies, Cherokees and Creeks, came to Coffee’s aid and forced the Red Sticks to withdraw, ending the battle. Along with Donelson, three other Americans were killed, compared to 45 killed or wounded Red Sticks.

Casualties were light, but Jackson’s recruits were insufficient in numbers and training to attack Tohopeka. Once again, Jackson headed back to Fort Strother. The Red Sticks were a tenacious foe. Although they had received the worst of it in three conflicts with Jackson, they pursued him to instigate a fourth. They realized that this was an adversary who would never stop until he or they were destroyed. They hated but respected Jackson, calling him “Sharp Knife.”

As the Tennesseans crossed Enotachapco Creek, the Red Sticks descended upon them. The rear guard gave way, leaving Carroll and 25 men to face the bulk of the enemy. The cannons were still in midstream when the attack commenced. Artillery Lieutenant John Armstrong ordered his men to rush to Carroll’s aid while he helped push the six-pounder into position. After blasting the first round of case shot into the Red Sticks, Armstrong fell wounded. “My brave fellows,” he said, “some of you may fall, but you must save the cannon.” Other troops crossed back to assist Carroll and Armstrong. The Red Sticks retreated, leaving behind 200 dead. The Tennesseans suffered 20 killed and 75 wounded. It was their costliest victory yet, but the frontiersmen were able to return to Fort Strother without further harassment.

The Execution of John Woods

Shortly after returning to the fort, Jackson began to receive a steady stream of good news. Governor Blount, stung by Jackson’s earlier chastisement, had called for a new set of volunteers. Some 2,000 East Tennessee volunteers, then 2,000 West Tennessee volunteers, reported for service and were sent south to Fort Strother. On February 6, 600 men of the 39th U.S. Infantry Regiment arrived, commanded by Colonel John Williams. After dealing with militia and volunteers for so long, Jackson was thankful for a core of full-time professionals to set a standard of discipline. Among the 39th’s ranks was a young ensign, Sam Houston. Like Red Eagle, Houston had lived among both whites and Indians. As a teenager, he had run away from his Tennessee home to live with the Cherokee. They named him “Raven,” and he remained with them until war broke out and he sought new adventures fighting the Creeks.

Following the arrival of the new army—Jackson’s third of the campaign—he set about building a cohesive, disciplined force to deliver the final blow to the Red Sticks’ rebellion. He became increasingly intolerant of any failure, even among his officers. Cocke was arrested when his volunteers refused to honor their six-month commitments—they were envious of the three-month commitments offered by Blount. Cocke was court-martialed and acquitted, but the ongoing controversy denied him a share of the glory in the final victory in the Creek War.

Back at Fort Strother, an 18-year-old recruit named John Woods suffered an even worse fate. Woods was a member of a unit that had become infamous for insubordination, although the reputation had been earned before Woods volunteered for service. Early one morning, following a night on watch duty, Woods received permission to return to his tent for something to eat. While doing so, he was interrupted by an officer who brusquely ordered him back to duty. Perturbed and hungry, Woods kept eating. The war of words intensified until Woods leveled his rifle at the officer. Friends calmed him down, and he lowered the weapon.

Jackson, informed that nothing less than a mutiny was under way, ordered Woods arrested and tried. A court-martial found him guilty and sentenced him to death by firing squad. Most expected the general to commute the sentence; usually only regular army commanders, not volunteer or militia commanders, imposed capital punishment. However, Jackson ordered the execution carried out. Woods’s death would be used in future political campaigns by Jackson’s opponents to claim that he was a merciless, tyrannical chieftain.

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend

Woods died on March 14, 1814. That same day, the Tennesseans departed Fort Strother and headed to Tohopeka for a final showdown with the Red Sticks. The enemy had been busy at Horseshoe Bend. Across the narrow neck of the enclosure they had constructed a breastwork of logs and earth, varying from five to eight feet in height. The wall had a number of portholes, ideal for firing by the defenders. It was an extraordinarily complex structure for an Indian tribe to build and suggested that a European influence was at work—possibly English spies.

Jackson sent Colonel Williams south to establish an outpost while he and about 4,000 men, including Creek and Cherokee allies, moved southeast toward Tohopeka. On the morning of March 27 they arrived north of the village. Estimates placed the Red Sticks’ strength at 1,000 warriors, with another 300 women and children living among them.

At 10 am, Jackson ordered Coffee to cross the river with his cavalry, Indian allies, and scouts. Somehow they made the crossing without the Red Sticks taking notice. Jackson positioned his two artillery pieces (a three-pounder and a six-pounder) 80 yards from the breastwork. At 10:30, they commenced firing. The cannons weren’t meant for this type of mission, and their light balls bounced harmlessly off the wall, prompting the Red Sticks to taunt the invaders. Meanwhile, their prophets danced on the roofs of the huts, proclaiming their invincibility and the impotence of their adversaries.

For two hours, the two sides fought to a stalemate. To the south of the village, across the river, Coffee and his men lay in wait. Cherokee swimmers crossed the river, cut free the canoes floating there, and used them to ferry the force across. Once over the river, the troops began to set fire to the huts. Jackson, from his position in front of the breastwork, spotted the smoke. Immedately, he gave the order to charge. The men of the 39th Infantry stormed the breastwork. Major Lemuel Montgomery was the first to make it to the top; he was killed instantly by a shot to the head. Ensign Houston took his place and received a barbed arrow in the thigh for his troubles. It didn’t stop him, and he leapt down into the fortification, establishing a much-needed foothold for the others.

The Red Sticks were fighting for their homes. Once they realized they were surrounded, the fighting became increasingly desperate. They would not surrender or ask for mercy; the Tallapoosa soon swelled with corpses. Menewa, Red Eagle’s lieutenant, sustained seven wounds, but survived and made his way to safety. A stalwart few barricaded themselves in some brush by the breastwork. From there, they resisted until night, when the Tennesseans set the brush on fire and picked off the final holdouts as they attempted to escape the flames. “The carnage was dreadful,” Jackson later wrote to Rachel. Some 557 Red Sticks were killed on the ground, with another 300 dead in the river. Almost all the women and children survived, having been moved to safety before the battle. The victory was complete except for one important detail: Red Eagle was missing.

The Tennesseans and friendly Indians lost 65 killed and 206 wounded. Sam Houston, already wounded in his thigh, suffered two additional gunshot wounds to his right shoulder. So terrible was his appearance that the medic performing triage at the scene classified him as lost. He was placed on a litter and moved 60 miles to Fort Williams, without medical aid. Two months later, when he finally returned to his mother’s house, she could only recognize him by his eyes.

Peace Talks at Fort Jackson

Jackson resupplied his force at Fort Williams. He then moved on the Hickory Ground, the sacred land of the Creeks. He occupied the old French fort, Toulouse, renamed Fort Jackson, near the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers. There, Red Stick chiefs came to surrender. One day, a lone Creek entered Fort Jackson, leading a black horse with a recently killed deer strapped to it. He was pointed to Jackson’s tent. Upon seeing Jackson, he identified himself as Bill Weatherford. “How dare you ride up to my tent after having murdered the women and children at Fort Mims?” Jackson thundered. Weatherford insisted that he had attempted to save the women and children at Fort Mims. He had come not on his own behalf, he said, but to beg for mercy for the women and children.

Jackson was impressed and invited Weatherford into his tent to discuss it further. He made it clear that Weatherford must consent to all peace terms. Weatherford replied: “Once I could animate my warriors to battle, but I cannot animate the dead. My warriors can no longer hear my voice: their bones are at Talladega, Tallussahatchee, Emuckfaw and Tohopeka. While there were chances of success, I never left my post, nor supplicated peace, but your people have destroyed my nation. You are a brave man. I rely upon your generosity.”

Having sworn off further warfare, Red Eagle once again became Bill Weatherford. He retired to plantation life, but he was obliged to relocate several times to avoid retribution at the hands of relatives of the Fort Mims victims.

Next for Jackson came the business of peace. The War Department had originally intended for General Pinckney or Colonel Benjamin Hawkins, an old Indian hand, to draw up the terms, but Jackson’s allies lobbied successfully to give him the honor. That summer Jackson revealed the proposed treaty to a collection of friendly Creek chiefs. Most of the terms were reasonable: turning over those prophets responsible for inciting hostilities, allowing the United States to establish roads through Creek country, and ending all communications with British and Spanish agents. The government would provide sustenance for the Creeks whose land was destroyed or confiscated. The most shocking demand was for 23 million acres of land—fully half the original Creek domain. Not only would the rebellious Red Sticks be punished, but also those Creek tribes that had sided with Jackson and fought alongside the Tennesseans.

His Indian allies complained, but Jackson was in no mood to negotiate. However, the proud Creek chiefs made one request: of the land to be turned over, three square miles should go to Jackson—not as a prize of war, but as a gift of gratitude from the Creeks for his valiant defense of their homes. To conclude the treaty expeditiously, Jackson accepted. With the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson, the Creek War came to an end—and none too soon. Napoleon had lost his empire and had taken up residency on Elba the previous May. The British Empire could now focus all its power on the American war. The 7th Military District, containing Louisiana and the Mississippi Territory, required a new commander. Jackson received the title and a commission as a major general in the regular army. Affairs on the Gulf Coast demanded his immediate attention. He and his troops headed south.

Jackson’s victory in the Creek War ended the threat of a united Indian force in the War of 1812 (Tecumseh had been killed the previous year at the Battle of the Thames). With the Mississippi Territory cleared of hostile Indian attacks, the path was clear to move troops swiftly from the north to the Gulf Coast, starting with Jackson himself. If the British wanted a foothold on the southern coast of the United States, they were going to have to fight Old Hickory for it. In the end, as they discovered at the Battle of New Orleans a few months later, it would prove to be an uneven fight.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments