By James Reynolds

For Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen interned in enemy prison camps during World War II, escaping was regarded as their unwritten duty.

The majority suffered great hardships—denied adequate food, clothing, medical supplies, and proper shelter—but they tried to make the best of it, watching the skies for Allied planes and patiently waiting for eventual liberation. But there were also many others who doggedly refused to accept their fate. They formed escape committees in their squalid wooden barracks, scrounged resources, and devoted their energy and ingenuity to hoodwinking their captors and devising ways to break free. Numerous tunnels were secretly and laboriously dug with whatever primitive tools they could fashion, wire fences were cut, and some prisoners managed to flee, reach neutral territory, and eventually rejoin their own forces.

But many faced the heartbreak of swift recapture after weeks and months of toil. Punishment and the loss of basic privileges usually followed while their captors sought to make the camps even more secure. Brutal treatment and worsening conditions, however, could not quell hope, so the escape attempts continued.

Some prisoners escaped and were recaptured numerous times. Yet they still kept trying and in so doing provided a much-needed lift to their comrades’ morale. One of the most remarkable of these heroes was William Ash, a boyish, tousle-haired fighter pilot from Texas who made no less than 13 escape attempts from German prison camps between 1942 and 1945. He was tortured by the Gestapo and went over, under, and through barbed-wire fences, walked out while disguised as a Russian slave-laborer, and even tunneled through a latrine.

Interned variously in France, Poland, Lithuania, and Germany, Ash broke free six times and was recaptured on every occasion. But he never gave up his career as an “escape artist,” and finally reached freedom in the spring of 1945 when the European war was waning. He became celebrated as a real-life “cooler king.”

William Franklin Ash was born on Friday, November 30, 1917, in Dallas, Texas, before the oil boom, and later remembered curious citizens gathering when the city’s first traffic light was installed. His father was a struggling salesman of women’s hats, and the boy recalled him “forever having his automobile, on which his livelihood depended, carted off by the repo-men, like a cavalryman having his horse shot from under him during a rout.”

Life was hard, and young Bill helped support his family by doing odd jobs and selling magazine subscriptions from door to door. He worked later as a shelf-stacker and cub reporter for the Dallas Morning News, where he remembered staring at the bodies of outlaws Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker in their bullet-riddled getaway car after they were ambushed by Texas Rangers and sheriff’s deputies in Louisiana in May 1934.

Energetic and ambitious, Bill managed gradually to save enough money to put himself through the University of Texas in Austin. He was an exceptional student, and, despite holding down several jobs, graduated with top marks in liberal arts. But rewarding job opportunities were scarce during the Depression, so he had to be satisfied with operating an elevator in a local bank. One day, he bumped into a former professor who asked if the bank realized that he was an honors graduate. “Yes,” young Ash replied with a wry smile, “but they’ve agreed to overlook it.”

Before long, the frustrated young man joined thousands of others hitchhiking on the roads and riding railroad boxcars from town to town in search of work. Rubbing shoulders with hoboes in shanty towns all over the Midwest, Bill Ash shared what little he had, developed sympathy for the needy, and became handy with his fists. At the time of the outbreak of war in September 1939, his travels had taken him to Detroit, Michigan, where he found himself getting involved in street brawls with supporters of the American Nazi Party.

In 1940, with Great Britain standing alone and German forces rampaging through the Low Countries and France, Ash became impatient with his own country’s neutrality. So, like a number of other concerned young Americans, he decided to offer his services to the Allied cause. He walked across the bridge from Detroit to Windsor, Ontario, and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. The move cost him his American citizenship, and he said later, “I tried to explain that I was not so much for King George as against Hitler, but they didn’t seem to care much at the time.”

After training as a pilot in Canada, Ash rode a troopship to Britain in 1941 and joined No. 411 Squadron of Royal Air Force Fighter Command as a flying officer. Through 1941 and into early 1942, he saw plenty of action as the squadron’s Spitfires escorted bombers, defended shipping in the English Channel, and flew low-level “rhubarb” sorties against German airfields, troop concentrations, and communication lines in northern France. Ash also flew escort for RAF bombers during an abortive attack on the 31,800-ton battlecruiser Scharnhorst as she sailed through the English Channel in broad daylight during Operation Cerberus.

Nicknamed “Tex” and popular with his fellow British and Commonwealth pilots, Ash took part in publicity drives during 1941 aimed at encouraging the United States to enter the war and calling for more Americans to follow his example and go to Canada as volunteers. When he touched down at his airfield after a cross-Channel mission one day, Ash was surprised by flashbulbs popping and a portly, jovial man in a suit being helped onto the wing of his Spitfire. It was Canadian Prime Minister William Mackenzie King. The two shook hands and exchanged good wishes.

On a spring day in 1942, Ash was returning from bomber escort duty over the Pas de Calais when he was set upon by half a dozen deadly German Focke-Wulf 190 fighters. They riddled his Spitfire, and his gun button was jammed. The young American flier could do nothing but turn into his attackers to minimize his profile as they casually took turns trying to blow him out of the sky. He continued to press his gun button and defiantly shouted, “Bang, bang!” But his combat flying days were over. Ash was forced to crash land near the village of Vielle-Eglise, where a French war widow sheltered him from the enemy.

Ash was put in contact with members of a local Resistance group, and they helped him make his way to Paris, where he hid for several months. But he grew restless and sauntered out into the streets, visiting art galleries and swimming baths. Before long, however, his luck ran out and he was picked up by the Gestapo. Thrown into the infamous Fresnes Prison, he was beaten, tortured, and singled out for execution as a spy. However, shortly before he was to face a firing squad, Ash was “rescued” by a Luftwaffe officer who feared that his death would lead to reprisals against downed German fliers in Britain.

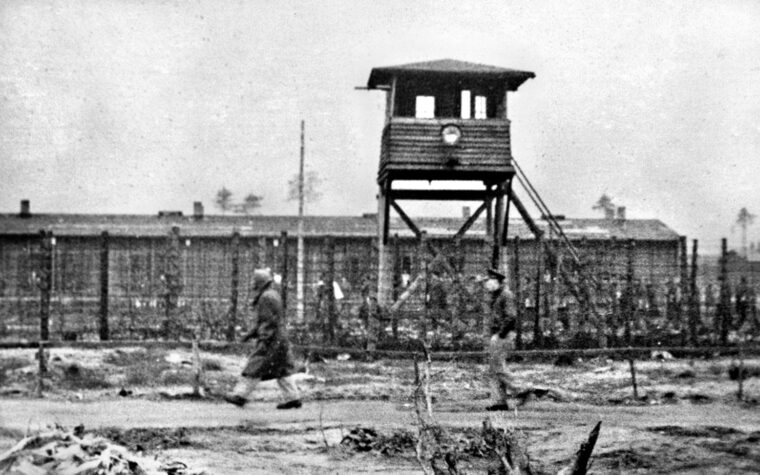

Ash was sent to Stalag Luft III, a sprawling, remote prison camp near the city of Sagan in Upper Silesia, 100 miles southeast of Berlin and 60 miles from the Polish border. Ten thousand Allied fliers—mostly British, Commonwealth, as well as some Americans, Norwegians, and Dutchmen—were held in five separate compounds behind high barbed-wire fences and machine-gun towers. Life was grim, but the prisoners kept their spirits up with elaborate escape plans.

Scrounging whatever material they could find, they stitched civilian clothes, forged identity papers, drew maps, made compasses, accumulated iron rations from their infrequent Red Cross parcels, and painstakingly dug four 300-foot tunnels whimsically named Tom, Dick, Harry, and George. The efforts were overseen by two decorated RAF officers who consistently and successfully pitted their wits against the enemy—Squadron Leader Roger Bushell and Flight Lt. Ley Kenyon. One of the tunnels was started from the middle of a compound—its entrance hidden under a wooden vaulting horse that was in constant use by a squad of gymnasts while digging went on underground.

Stalag Luft III became famous because of its “escape artists,” including Ash, who soon won the admiration of his comrades. Shortly after his arrival, the Texan became firm friends with Paddy Barthropp, an RAF pilot in the Battle of Britain. They made several escape attempts together. During the first of these, they hid in a shower drain under the shower huts in the hope of escaping after lying low for a few days. They fortified themselves with “the mixture,” a high-energy concoction of chocolate, oats, and dried fruit donated by other prisoners from their Red Cross parcels. When they were discovered, Ash and Barthropp decided not to let the mixture fall into enemy hands. They were eventually hauled out with chocolate-smeared faces and marched off to solitary confinement in “the cooler.”

Solitary confinement, said Ash later, was like “being sent back to ‘go’ when playing Monopoly, only with more bruises.” He made several more escape attempts, only to be recaptured each time. But he refused to be deterred. After being shipped to a camp for recidivist escapees in Poland, he and another Canadian pilot masterminded the digging of a tunnel extending several hundred yards from under a stinking latrine to beyond the perimeter. Leading the way for 30 other prisoners, the pair managed to break out. But all were eventually recaptured and Ash was sent back to Stalag Luft III.

One day, he made a daring climb in broad daylight over two barbed-wire fences flanked by machine-gun towers in order to reach a nearby compound where a group of prisoners was about to be dispatched to a new camp in Lithuania. Ash thought the chances of escape might be better there. After reaching the camp, he helped to dig another long tunnel.

Managing to break free, the determined Texan made his way through Lithuania to the Baltic Sea coast. He found a boat on a beach but was too weak to drag it down to the water’s edge. Spotting some men working in a nearby field, he asked them to help him. “We would love to,” one replied with a sly grin, “but we are off-duty soldiers of the German Army, and you are standing on our cabbages.” The chagrined Ash was swiftly returned to Stalag Luft III.

He was still languishing in the camp’s cooler when some of his comrades pulled off the most famous POW escape of World War II on the night of Friday, March 24, 1944, while 811 RAF bombers were pounding Berlin. Seventy-six RAF officers, including Greeks, Frenchmen, Czechs, Poles, Dutchmen, and Norwegians, crawled through a long tunnel and emerged outside the Sagan camp. A Dutch pilot and two Norwegians managed to reach Stettin in Prussia and sail from Sweden to England, but the rest were captured, three of them close to the tunnel exit. Squadron Leader Bushell reached Saarbrucken before being seized.

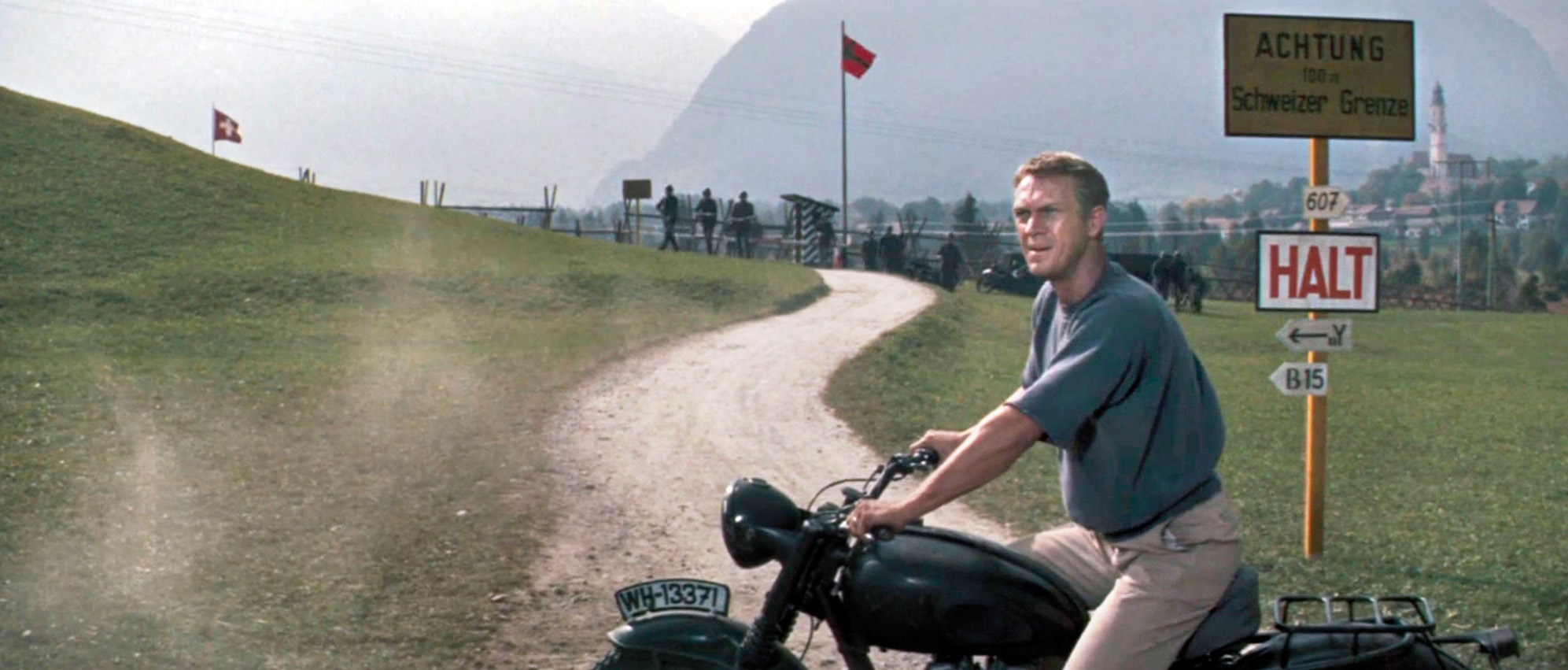

The mass breakout was described in a book, The Great Escape, by Royal Australian Air Force veteran Paul Brickhill, and then was depicted in a big-budget 1963 film epic of the same name. Directed by John Sturges, it starred James Garner, Richard Attenborough, Donald Pleasence, Charles Bronson, and James Coburn. Steve McQueen portrayed a fictional character, Virgil Hilts, the “Cooler King,” based on several sources, including William Ash. The film was handsomely staged, highly entertaining, and a box office hit, but considerable liberties were taken with historical fact. Americans took no part in the real breakout, and one of the film’s best remembered scenes—with McQueen vaulting over a fence on a stolen German motorcycle and heading for neutral Switzerland—was Hollywood fantasy.

On the personal orders of Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, at least 50 of the recaptured Sagan escapees were handed over to the SS and swiftly executed without trial. An official German statement said that the victims were shot “while resisting arrest, or attempting a further escape after being recaptured.” Their names were posted at Stalag Luft III as a warning to others, and Hitler fumed to SS chief Heinrich Himmler, “You are not to let the escaped airmen out of your control!”

The murders and threats cast a pall of gloom over Stalag Luft III, but hope flickered on because the prisoners sensed that the Allies were gaining the upper hand over the enemy. The German offensive through the Ardennes had stalled, while the British, American, and Canadian Armies were nearing the River Rhine, and Soviet forces were rapidly pressing in from the east.

When Christmas 1944, came bleakly with bitter cold and six inches of snow dusting the pine forests around the camp, the shivering prisoners strung up decorations fashioned from old tin cans in their wooden huts and listened to an 80-voice choir sing Handel’s “Messiah.” Supplies of Red Cross parcels had dwindled, but almost miraculously a batch arrived containing canned turkey, plum pudding, cigars, cigarettes, and candles. The American prisoners in the west compound were even treated to a visit from Santa Claus, riding a small wagon pulled by two men dressed as reindeer and tossing out bundles of mail.

In January 1945, word spread that the Germans were going to evacuate Stalag Luft III and march the prisoners out. There was no time to be lost. The Soviet Army had launched a winter offensive on a 300-mile front and was now only 60 miles away. A fresh batch of Red Cross parcels was opened, and the prisoners, who had been on restricted rations since September, were encouraged to eat what they could to ready them for what lay ahead outside in Germany’s worst winter for 50 years.

Flying Officer Ash and the rest of the Allied prisoners were force-marched out in late January, heading westward for POW camps at Luckenwalde, south of Berlin; Marlag Nord, outside Bremen; Nuremberg, and Moosburg, near Munich. They were glad to be out of confinement, but it was a miserable, exhausting ordeal for both the prisoners and their guards as they endured driving snow, sleet, and temperatures that fell to 17 degrees below zero while trudging along frozen roads and through ice-clad forests. Some pulled makeshift sleds carrying their scant belongings. Frostbite, jaundice, scurvy, and dysentery took a heavy toll, and men fell asleep while marching. Subsisting on frozen corned beef, Spam, and whatever else they could save from their Red Cross parcels, they slept in barns, cowsheds, and pigsties at night, and plodded on day after day.

The bedraggled, weary prisoners jostled on the roads with increasing numbers of German soldiers and refugees, often exchanging sympathy, as all fled westward from the Russians. The Allied captives were occasionally surprised and cheered by instances of German hospitality. An old village woman offered cups of acorn coffee, a Wehrmacht field kitchen doled out horsemeat stew, and in one town women had set up tables on a street and were offering soup, bread, sausage, coffee, and God’s blessing. “You boys will be going home soon,” predicted the headmistress of the local school.

The surviving prisoners eventually reached their new camps by way of trucks and cattle trains, but Flying Officer Ash was not among them. He had abandoned the forced march and walked to freedom across a battlefield to the Allied lines. The war was over for him.

After returning to England, Ash was appointed a Member of the British Empire, awarded British citizenship, and obtained a veteran’s scholarship to read philosophy, politics, and economics at Oxford University’s Balliol College. He then joined the BBC and worked alongside a young Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who became a lifelong friend and influential Labour Party cabinet minister. Sent to India as the corporation’s main representative, Ash married an Indian woman and embraced Prime Minister Pandit Nehru’s brand of socialism. When he returned to England in the late 1950s, he was a hard-boiled leftist, active in “street politics” and the anti-fascist movement. But his revolutionary tendencies were too much for the BBC, and he was fired.

He managed to stay in the radio drama department as a script reader. Beginning in the 1960s, Ash wrote several novels, including Choice of Arms and Ride a Paper Tiger, but politics remained his chief interest. The British Communist Party barred him for being a maverick, so he co-founded an offshoot group and started publishing an academic monthly study, Marxist Morality. While continuing to read scripts for BBC Radio, he chaired the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain for several years, helped to encourage young authors, and served as literary manager of a London theater, the Soho Poly. Ash’s book, How to Write Radio Drama, remained the most authoritative on the subject for more than 20 years.

His remarkable war exploits were mostly unknown until his memoir, Under the Wire, was published in 2005. Co-written with Brendan Foley, it was a best-seller and rewarded Bill Ash with belated recognition for his courage and daring. Asked on a BBC program the secret to his late success, he replied, “Easy. All you have to do is dig a hole and wait 60 years.”

Ash died at the age of 96 on April 26, 2014. His first marriage to Patricia Rambault was dissolved, and he was survived by his second wife, Ranjana, and the son and daughter of his first marriage.”

Join The Conversation

Comments