By David H. Lippman

Nobody knew it in the 6th Armored Division’s 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, but the tide of the Battle of the Bulge had turned by the time the outfit moved into snow-covered fields and forests near Bastogne. Adolf Hitler had given up on his overly ambitious plan to force the Meuse River, split the Allied armies in half, and seize the major Belgian port city of Antwerp.

One major reason for the German failure had been the determined American defense of the Belgian town of Bastogne by the 101st Airborne Division and elements of Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division. Now the “battered bastion” had been relieved by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s Third Army, and Hitler had ordered his elite SS panzer divisions to regroup and seize the consolation prize. The hardest fighting for Bastogne lay just ahead. So did the hardest ordeal in the life of a young Jewish GI from New Jersey named Robert Max, who would endure the multiple traumas of combat, captivity, slave labor, and escape from the Nazis, returning home at half his body weight, but surviving to speak about his experiences for decades, inspiring generations yet unborn.

Bob’s life story began in 1922 in New Jersey. Born in Newark and raised there and in neighboring South Orange, Bob won sprinting medals in junior high school and played football in leagues for teenagers, often against high school teams. Bob’s father owned a wholesale milk business, which resulted in long hours and road trips. Bob’s older brother Lester was often a father figure to him.

As World War II hit America, Bob enlisted in the Army on October 26, 1942, and was assigned to the 9th Armored Infantry Battalion, part of Maj. Gen. Robert Grow’s 6th “Super Sixth” Armored Division, under III Corps, which fought under Patton’s command in the breakout from Normandy, in Brittany, and in the Lorraine. When the Germans launched the Battle of the Bulge on December 16, 1944, the 6th Armored, like the rest of III Corps, was pulled out of its eastward attack into the Saar, turned 90 degrees, and hurled northward to relieve Bastogne. The spearpoint of Patton’s drive on Bastogne was his veteran 4th Armored Division, with the 6th right behind it.

The 4th Armored did its job, hooking up with the legendary “Screaming Eagles” right after Christmas. But the 4th Armored was worn down by the fighting, and the 6th Armored moved in after them, taking over the 4th’s positions as 1945 began.

At the same time, the German 1st SS Panzer Corps stormed down on Bastogne, its attack headed by the 9th “Hohenstaufen” SS Panzer Division and the 12th “Hitler Jugend” SS Panzer Division. The latter outfit, which had already amassed a hefty record of bravery and butchery, was based on a cadre of former Hitler Youth filled with Nazi rhetoric and lavishly equipped with Krupp tanks and guns. In Normandy, 12th SS men had mown down captured Canadian prisoners in cold blood, an incident that led to Canada’s only postwar war crimes trial.

Adding to the misery was the terrible weather. After a brief period of clear weather that enabled American and British airpower to savage the German armor, temperatures dropped again, burying men in intense cold and snow.

The two SS divisions slammed into Bastogne’s weary defenders from the northeast on January 5 in a two-day attack that cost the 101st Airborne 53 dead, 393 wounded, and 91 missing, a 4.1 percent loss in personnel. The 6th Armored suffered 62 dead, 215 wounded, and 41 missing, for a 2.97 percent personnel loss. The Germans forced the 6th Armored’s Combat Command B to give up the towns of Magret and Wardin.

Despite these losses, this last German thrust was ultimately stopped cold. At the close of the day, German Field Marshal Walther Model, commanding Army Group B and the whole Nazi offensive, ordered the 9th SS Panzer Division pulled back to cover his crumbling northern front. The 12th SS Panzer Division was ordered to withdraw.

None of these moves mattered to Bob Max, though. Early on the morning of January 6, his main concern was food. He hadn’t eaten, and he was sent to the rear to get some chow and a little rest. There, he was told that the always fragile telephone lines to the forward positions were broken, and Bob volunteered to find out what was going on. He saw a jeep and commandeered it.

Bob headed off with five other soldiers picked almost at random. Reflecting decades later, Bob said, like many GIs, “I always loved driving in a jeep anyway.” He took off to where he was told his unit was supposed to be, heading down a road. They knew they were near the front line when they saw a wrecked and burning American tank by the side of the road.

“As we rounded a curve, we saw a tank appear in front of us with an 88mm gun pointed directly at us,” Bob recalled in 2015. It was likely one of the 12th SS Panzer Division’s many self-propelled assault guns, but it packed more firepower than Bob’s jeep, which was armed with only a machine gun.

“We had nowhere to go,” Bob said. “We had to get out of the jeep. I jammed the brakes and went into a ditch; we were forced to abandon the jeep. I saw a shack off the road. One of the guys dismantled the machine gun. We took off and ran across the road under rifle and machine-gun fire. One of our guys was hit in the back. The bullets continued to pour in.”

One of the American soldiers set up the machine gun in the shack’s bay window and opened fire in the direction of the enemy. When the gunner was injured by a Nazi bullet, Bob instinctively jumped in front to replace him and resumed firing, fully exposed to enemy fire.

“The Germans were shooting at us from bunkers where they were well protected,” Bob said later. “I shot at everything I saw move and hit many enemy soldiers.”

All day long Bob and his band fought back against the entrenched German troops. By late afternoon, the Americans’ ammunition was dwindling, the survivors were in agony from their wounds, and Bob and his crew had to decide what to do—hide, flee, or surrender.

“The shack had a trap door leading to a cellar, so when our ammunition eventually ran out, we decided to hide there temporarily. Our plan was to lead the Germans to suspect we had all been killed or fled, and then under the cover of darkness infiltrate through enemy lines. But when the Nazi soldiers entered the shack, one of our wounded moaned, which gave us away. When a German tapped on the cellar, I pushed up the door and saw a vision that remains clear to me today—a ring of black automatic weapons held by hooded Germans in white snowsuits, with their fingers on the triggers,” Bob said.

“One of them, who looked like a sergeant, motioned for us to come up, so we did, and they took away our weapons.”

All of the Americans were taken away at that point, leaving Bob alone with a German sergeant who forced Bob to check the shack for booby traps. Next the sergeant forced Bob to cross the road, his gun barrel jammed into Bob’s back, toward the German bunkers. American artillery was shelling the area, and both shrapnel and tree fragments were flying through the air, creating a terrifying situation. “If that hot metal pierces your skin,” Bob said later, “you’re finished.”

Nevertheless, Bob dashed across the road to the bunkers, and the Germans climbed into them, leaving Bob unprotected outside, at the mercy of the elements, American artillery, and German rifles.

Bob tried to climb into a German bunker to be safe from the shelling, at least, but the German sergeant waved him off, saying, “Nein, nein.”

Bob realized his life was probably on the line. “What are you going to do to me?” Bob asked the sergeant.

“I have to shoot you,” the sergeant said, in English.

“My impulse was to run,” Bob said later. “Just to get to the road and sprint down it like I did as a sprinter in school. I saw the burning American tank across the road, and from the light of its flames, I could see bunker after bunker, and each had a little silhouette of a machine gun. I knew that if I started running, I wouldn’t get out of the starting block. So all that was left was conversation.

“I started talking with the German, and he asked me, ‘What are you Americans doing here? This is not your war.’”

“I said, ‘You made it our war,’ and the talk went on. Then the German reached into his pants. I thought he was going to bring out his pistol and shoot me, but it was his wallet.”

As shellfire and tree fragments rained down, the German sergeant showed Bob photographs of his family—wife, son, and daughter—and said, “Next year, we’ll be in New York City.”

Bob was astonished by “how assured the German was that Hitler would conquer the world. But as he looked at his wallet and his beautiful kids, I could see his attitude changing.” Finally he said, ‘For you the war is over. I’m sending you to a prisoner of war camp.’”

It was a “moment of elation” for Bob, knowing that he would not die. The German added, “You killed many of our men, but you fought well.”

The sergeant signaled some guards, issued orders in German, and the Germans took Bob away. “I don’t know what the orders were, but I assumed they were to take me to a POW camp.”

As Bob and his escorts hiked through the snow, the story became stranger. The party ran into an officer who took the guards aside and issued them new orders. Bob was taken not to a standard POW camp, but to a large group of prisoners in unfamiliar uniforms surrounded by armed German guards. Most of the prisoners did not speak a language Bob recognized.

In all likelihood, Bob was handed over to an SS-controlled work unit, made up of Eastern European POWs being used as slave labor.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, the Nazis captured vast hordes of Soviet POWs. The Germans ignored the various conventions on treating these POWs and used them as slave labor, often starving them. To escape their plight, numbers of these POWs actually volunteered to join the German Army and were sent to Normandy and other battlefields to fight the American and British invaders. But most refused to become turncoats and instead suffered and starved in labor units that built and rebuilt bridges, railroads, and roads, worked in factories and coal mines, and built fortifications behind front lines. Somehow Bob had joined one of these units.

“The Germans took my overcoat and gloves. I assumed this meant I would be sheltered and hopefully fed,” Bob said later.

This was not the German plan. “They marched us along a road at night, with lots of guards beside us. After a while, they pointed their rifles at us and told us to lie down on roads covered with snow and ice, which we did. That’s what we did for the next 82 out of 90 nights.”

Bob and his fellow prisoners marched through the sub-zero conditions of the Ardennes Forest under guard, lying down when ordered. He was unable to sleep, because he had to keep his fingers and toes, numb from cold and marching, moving to prevent frostbite. Periodically, the Germans fed them a crust of dark brown bread. The prisoners drank snow. “Whether we lived or died was of no importance to them,” Bob said later. “Some men dropped out and died. Some were shot.”

After a while, they were finally brought to a bomb-damaged railway line. There, the Germans ordered Bob and the other laborers to rebuild sections of track.

“We had to line up and carry a section of track on our shoulders,” Bob said later. “It was excruciating. We carried those track sections for miles at night. They showed us how to repair the tracks by replacing wrecked sections with the new ones, and then putting in new ties to make them secure.”

The prisoners had their own form of passive resistance against their SS guards, which they shared through hand signals with Bob. The slaves did not line the tracks up properly, kept the ties loose, or didn’t install the ties at all, so that the tracks could not bear the weight of trains.

“I was very proud of our sabotage,” Bob said. “We’d share our triumphs with looks and hand signals.”

Day after day, Bob and the men moved rails amid appalling conditions, sleeping in snow and ice. Bob’s right foot became enflamed with frostbite. The pain was so bad, he couldn’t walk in his shoes. But if he fell out of the marches, Bob knew he would be shot. Finally, Bob tossed one shoe over a hedge and wrapped a scarf around his aching right foot; the scarf was his injured foot’s only protection from exposure to the elements.

“That was my mode of transportation for the rest of the time I was in captivity,” Bob said. “It was a painful decision.”

Brutality was the rule in the labor gang. If men dropped out from weakness, they were left. If a slave went to help a fallen buddy, an SS guard would smash a rifle butt in his back—or shoot the Samaritan.

“When I was awake, I thought about food. I just kept thinking about foods I’d like,” Bob said later.

During this ordeal, more prisoners joined the group, seemingly at random. One of them was, astonishingly, another American POW, Myron Barringer, a farmer from Rushfield, Indiana.

At one point, the party of slave laborers found themselves spending a night in a barn, sharing it with cattle. Barringer helped Bob lie down underneath a cow and milk it, providing Bob with fresh milk direct from the source.

Through it all, Bob kept envisioning all the meals he would eat if he ever made it home—apple pie, lamb stew, veal chops, t-bone steak with onions and peppers, Italian sausage, gefilte fish, soft-shelled crab, tuna fish salad, chopped liver, egg salad, lox, cheese omelets. “I would see bacon bubbling in the pan,” he recalls. “I could even smell it.”

The endless cycle of marching, repairing train tracks, and more marching ended in the German town of Prüm at the southern edge of the Ardennes.

There the Germans gave the prisoners six crackers, each one inch in diameter; this was the meal for the day. “Later we were marched into Gerolstein, and that’s where we got a can of hot water with a small piece of potato.”

Next Bob was marched to Stalag XIIA at Limburg, which was a regular POW camp run by the Wehrmacht—heated barracks, straw mattresses, and fellow Americans. Bob found a GI playing “Yellow Rose of Texas” on a harmonica.

There, Bob took a look at his own face in a metal strip for the first time in weeks and saw that it was orange from jaundice. But now, at least, in a proper POW camp, Bob figured he would get decent food and medical treatment.

He was wrong.

Two days later, Bob and others were marched out of camp to a train station, heading east. Alongside were German troops moving in the opposite direction, to the front, to face the advancing Allied armies.

Bob and his group were loaded onto filthy German boxcars. The German high command had made a decision to withdraw the POWs they held east and west away from advancing Allied or Soviet forces, hoping to use them as last-ditch bargaining chips.

“Eighty of us were packed in a car designed to hold 40, body against body. One time a day, they threw in some scraps of hard brown bread. Men crawled on the floor to get crumbs and became animals,” Bob recalled. “It was survival of the fittest, and some became mentally deranged by the horrible conditions. The trains lacked latrines. Some died from malnutrition and at least one prisoner was killed by a German sergeant.”

Oddly enough, the German sergeant’s name was Eisenhauer, the Germanic version of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s last name.

After six days, the prisoners were unloaded from their train and ordered to march again. “I couldn’t take much more of this,” Bob said later. “I was always thinking about escaping, and I knew it was time to do so.”

Bob’s plan was to find a curve in the march route where the German guards—less numerous than in the Ardennes—could not see him and flee the group. He and two other Americans threw themselves through some hedges. The others he had been with went stolidly on, whether to support his escape or from force of habit he never knew.

Bob was no longer a prisoner, but he didn’t know where he was. He remembered that the train had passed through a town earlier and he later learned that it was Reichenbach, a small country town in Baden-Wurttemberg surrounded by rolling hills.

Avoiding human contact, Bob and the others walked through the hills and began hearing sounds familiar to any combat soldier—the roar of battle. He went down a hill to see if he was near advancing American troops and saw that he was actually near a staging area for German soldiers defending that portion of the shrinking Reich from the advancing U.S. Seventh Army, which was driving on Stuttgart, the Brenner Pass, and the reputed (but nonexistent) German “National Redoubt.”

So instead of GIs in olive drab, Bob saw German troops in feldgrau (field gray). He saw a white house in the distance, and the three Americans slipped away from the Germans to the house, sensing that it might be a safe place.

“A young guy came to the door and opened it. He saw me, with my shaved head, and tried to close the door. I shoved my left foot into the door and told my story,” Bob said. “Then an elderly couple came to the door and saw us. The woman offered us some soup with a few pieces of meat floating in the broth, which was delectable,” Bob remembered. “We could hear shells firing in the distance and realized we were near Allied lines.” The man pointed us toward a barn. We crawled there through several alleys following a map the man had written and stayed there in the hayloft above some cattle.”

When Bob woke up the next morning, he saw a German soldier on the ground beneath him, in suspenders and boots, milking a cow. Some of the hay in the loft flitted down near the German soldier and luckily fell behind him and did not reveal the Americans’ hiding place.

Bob and the other two hid in the hayloft the rest of the day. The next day, Bob looked down from the hayloft into a narrow alley and saw men in uniforms and helmets, but he wasn’t sure if they were American or German. Then he saw an olive drab-painted vehicle drive past, a big white star stamped on the side. The three Americans half ran, half crawled to meet the GIs.

“The GIs who met us had a real shock, faced with three emaciated survivors who looked half-human. They took us in their arms. We were nearly unconscious. They laid us down and gave us chocolate, which tasted great. They saw my right foot was in that scarf and rushed me to the field hospital,” Bob said. He had lost half his weight and suffered 20 illnesses contracted from captivity and exposure. There, he was put on intravenous fluid and medication.

Bob was evacuated to the 1st General Hospital in Liege, Belgium, and from there to Paris. He was in the City of Light when he learned of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. While in the hospital, war crimes investigators took testimony from Bob about Sergeant Eisenhauer’s criminal behavior.

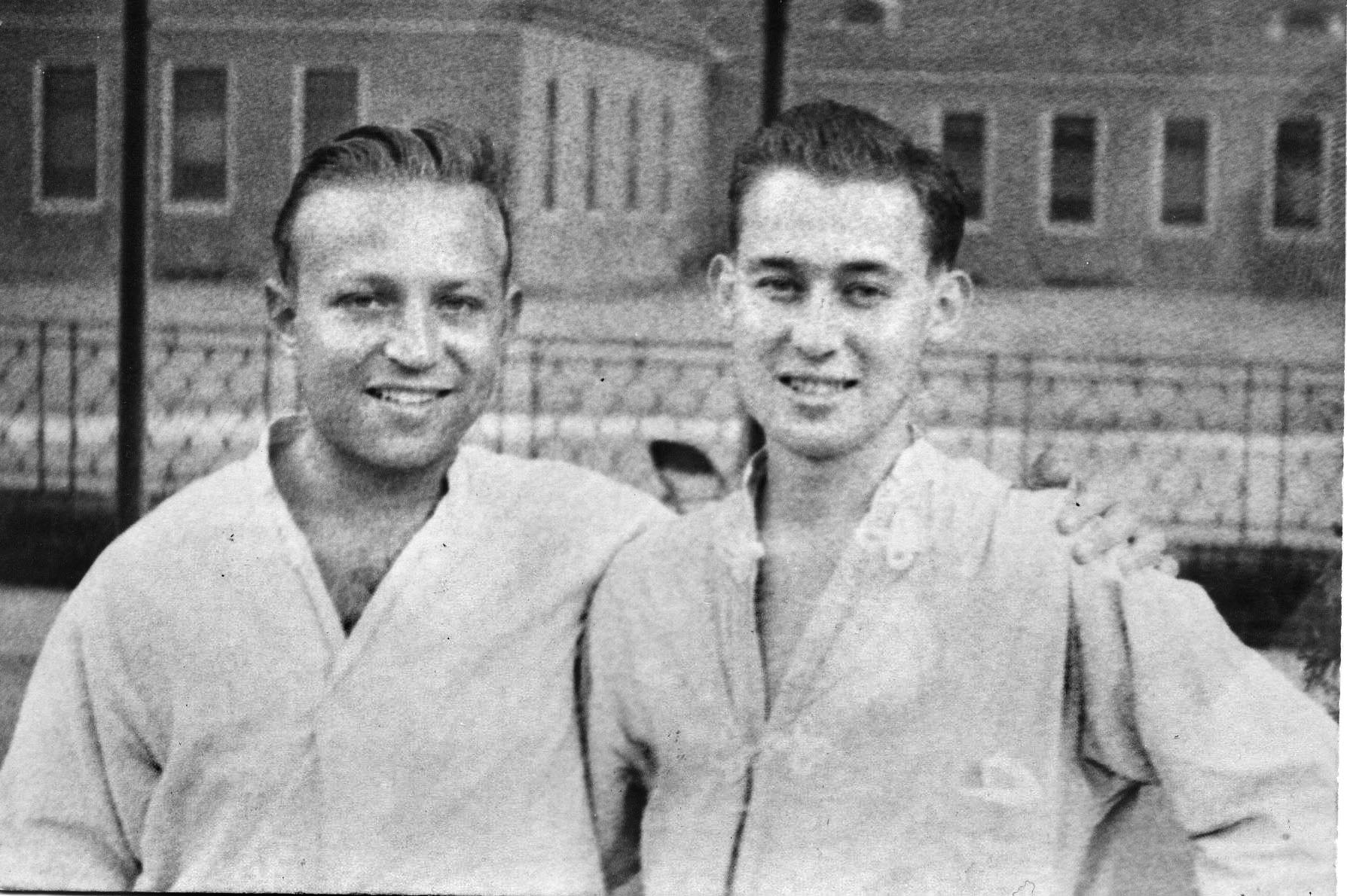

Bob’s disappearance had not gone unnoticed by the American chain of command. He was swiftly reported missing in action to his family, which included his older brother Lester, who was a communications man in another division in the Battle of the Bulge. When Lester saw Bob’s name on a routine list of missing personnel, he sent a message to other units to let him know if Bob turned up alive.

When Bob did, the word got through to Lester Max on a new list of recovered MIAs being treated, and Lester immediately fired off a note home to New Jersey to let their parents know that Bob had survived the ordeal.

“It was the most dramatic thing,” Bob noted. “Lester raised me, and my family learned from him that I was alive before they got the telegram from the War Department.” Lester also survived the war.

Bob was evacuated to Halloran General Hospital on Staten Island to recover from his wounds and suffering, and started receiving medals—a Purple Heart with an oak leaf cluster, three bronze campaign battle stars, and decades later, the New Jersey Distinguished Service Medal.

It took Bob a year to recover from the wounds, illnesses, and injuries he suffered. He recorded those in a little brown notebook a nurse had given him: trench fever, acute dysentery, malnutrition, pyoderma, frozen feet and hands, trench foot, swollen legs, fallen arches, sinusitis, beri-beri, typhoid, jaundice, bronchitis, and a back injury. He had lost 61 pounds.

He still has the little notebook today and something more important: his Army dogtags, a Mezuzah and Star of David attached to them.

Today, Bob lives at home in Summit, New Jersey. In his 90s, he is still active in the Max Foundation, which he and his wife established at Ohio University and with community work. He still lectures on his experiences during the war. He is turning his life into a book. He also has thousands of letters he has received from students over the years, thanking him for giving his lectures. “They show that each of those kids knows something. What we teach lasts a lifetime,” Bob added.

The letters make Bob pause, as he did on World War II battlefields more than 70 years ago. “When I saw somebody who was killed, I would pause and look at that individual and think, ‘That family will never be the same again.’”

Author David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He has written on a number of topics and has maintained a website detailing the daily events of the war.

It was a genuine privilege to interview this gentleman and hear his stories.

Like many former PoWs, he suffered PTSD from the experience. One of them was, he told me, difficulty standing in buffet lines. That is a very common phenomenon in former PoWs.