By Dorraine Fisher

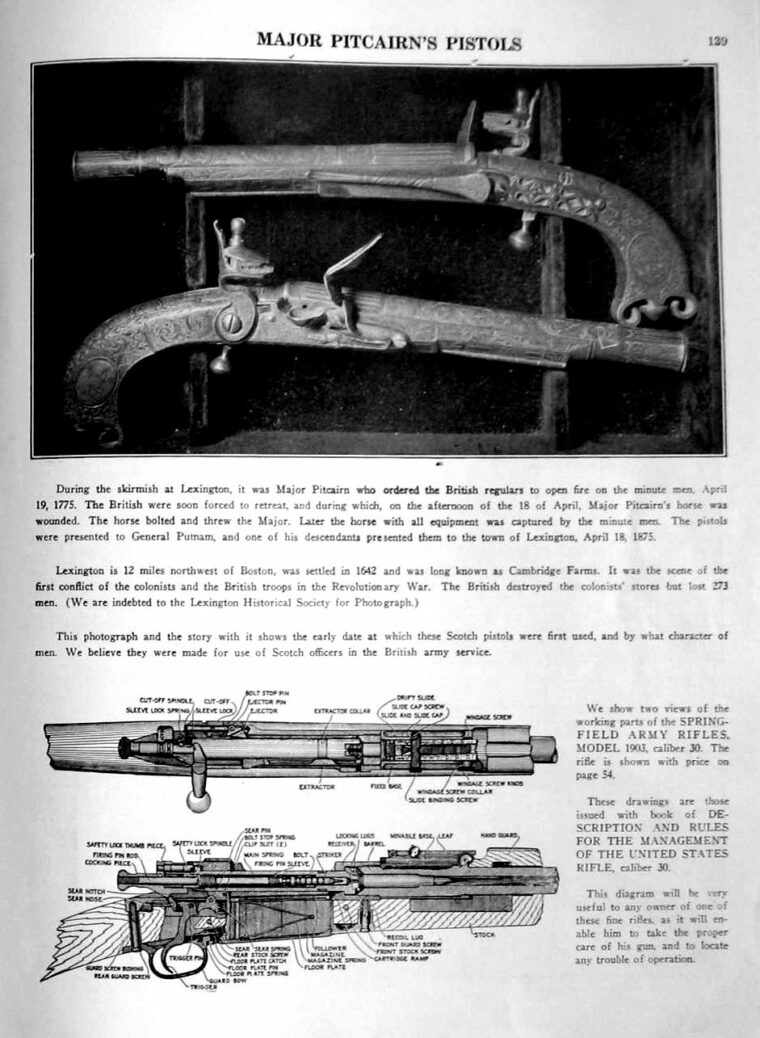

In central New York, 50 miles north of New York City on the Hudson River, is a small spit of land known as Bannerman Island. Originally called Pollepel Island, the tiny island was noted for tales of ghosts, and the local Native Americans would dare to visit it only during daylight. Early Dutch settlers used the island as a signpost marking the end of a rough passage through the Hudson highlands, and it also served as a strategic defense point for the patriots during the Revolutionary War.

Today, Bannerman Island provides a resting place for the ruins of a genuine Scottish castle, although the castle was not built to serve as a home. A closer look at the structure’s side reveals the raised-relief words “Bannerman’s Island Arsenal,” denoting the original purpose of castle and serving as a huge advertisement for the Bannerman family business. The sign could be seen clearly by passengers riding Hudson River steamboats and the New York Central Railroad.

Francis Bannerman VI: Businessman at 12-Years-Old

The Bannerman family was descended from the legendary Scottish clan MacDonald, which had been largely wiped out by the rival Campbell clan in a massacre at Glencoe in 1692. The Campbells had sworn allegiance to the English throne, but the MacDonald clan refused to offer a similar pledge of loyalty, which prompted the slaughter by the Campbells of the MacDonald males between the ages of 12 and 70. The name of Bannerman is said to have originated during the battle of Bannockburn in 1314 when a family member heroically rescued a captured banner from the enemy and escaped into the hills. The Scottish king Robert Bruce bestowed upon him the honor of “banner man,” which ultimately became the family name.

Francis (Frank) Bannerman VI immigrated to the United States with his parents from Dundee, Scotland, in 1854, when he was three years old. The family settled in Brooklyn, where Frank’s father, true to the family name, began the business of reselling flags and ropes that he had purchased at local Navy auctions. He was accompanied by young Frank, who soon began making money on the side by collecting scrap items from the harbor and reselling them.

At the onset of the Civil War, Frank’s father taught him all he needed to know about how Navy auctions operated before he left to join the Union Navy, leaving the 12-year-old boy in charge of the family business. Frank promptly quit school to help support the family full time in the absence of his father. He dragged the river with a large grappling hook for scrap items to sell to local junk buyers, and he quickly learned to repair many of the items he found and sell them for a profit. By the time Frank was 14, his small, individual money-making projects had turned into a full-blown, thriving business. By the time his father returned from the war, young Frank had accumulated enough merchandise for the family to start one of the very first military surplus stores.

The U.S. Government Sells Surplus for Scrap

At the end of the Civil War, the United States government was left with huge stocks of military surplus, which it began auctioning off to buyers for scrap metal. Huge stocks of surplus arms also went onto the government auction block. Frank promptly bought up all the swords, cannonballs, guns, and bullets he could. He soon realized that he could resell the items at a nice profit if he sold them for their original purposes rather than for scrap metal. By age 20, the young junk dealer had become a successful secondhand arms dealer.

In 1871, with his father’s blessing, Frank VI started his own competing store. His business dealings quickly became legendary. He bought up thousands of Civil War carbines at rock-bottom prices and sold the bulk to a store in New York that retailed them for 69 cents apiece—a remarkably low price that makes one wonder what Bannerman himself paid for them. Bannerman once avoided exorbitant rail-freight charges on a shipment of cartridge boxes from California by chartering a clipper ship to deliver the goods to New York via Cape Horn.

The U.S. government generally smashed surplus arms before auctioning them off, much to Bannerman’s dismay since he considered it more important to preserve historic arms than to reduce them to scrap. In one government auction, some 11,000 guns were sold for scrap, including many surrendered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his legendary army at Appomattox. The government refused to accept Bannerman’s bid, stating that he would likely repair the smashed guns and put them up for sale in competition with the obsolete guns the government was trying to sell. Instead, the heirloom weapons were destroyed and sold as scrap metal.

Building the Armory on Pollepel Island

On a business trip to Ireland, Frank visited his grandmother in Ulster and met a young woman named Helen Boyce. The two were married on June 8, 1872, and eventually had three sons, Francis VII, David, and Walter. The two older sons continued the family business; Walter eventually became a doctor and moved to Massachusetts.

After the close of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Bannerman bought up 90 percent of its captured goods in a sealed bid. This became his most legendary and problematic purchase. The family had been storing its arsenal in a warehouse in Brooklyn, but due to the large quantities of black powder in the new purchase (an estimated 30 million rounds of ammunition), it became necessary to find a safer place to store the huge amount of hazardous goods away from populated areas. The city of New York would not allow them to be stored near occupied areas.

Frank’s son David discovered Pollepel Island in the Hudson River while taking a canoe trip. Situated approximately 1,000 feet from the east shore, it proved to be the perfect distance from the city for the storage of a huge arsenal. The Bannermans purchased it from owners Thomas and Mary Taft in 1900 after the owners stipulaed that they not use it for the sale of alcohol. Bannerman fervently supported prohibition and had no problem with the restriction.

Frank and his wife spent the next 18 years designing an elaborate castle and another, smaller structure that served as summer living quarters for the family. The house was graced by a large picture window with a view of the United States Military Academy at West Point. The couple built their castle in the Scottish tradition of their ancestors, with little professional help from contractors or architects. Plans included battlements, towers, and a genuine drawbridge. Mrs. Bannerman landscaped the grounds. They added four additional warehouses to the grounds, including one that was placed in the tower of the castle. Huge metal baskets hung from the castle’s corners, suspending gas-fed lanterns that burned through the night like torch lights. Armed guards and dogs paced the grounds day and night to keep out intruders.

The family lived virtually on top of hundreds of thousands of rounds of live ammunition, but there were only a few recorded mishaps. The danger of living on an arsenal was brought home forcefully to Mrs. Bannerman one day. She was lying in a hammock on the terrace when she decided to get a glass of iced tea. As she stepped into the house, she heard an explosion and turned just in time to watch a piece of the island’s powder house land in the middle of her hammock. Nearly 200 pounds of black powder had exploded and hurled debris. The sound of the blast could be heard nearly 50 miles away. Both the castle and the residence suffered extensive structural damage. Doors were blown off their hinges, and windows were broken in homes in nearby towns from the enormous explosion.

Despite the alarming incident, the Bannerman family by 1900 had become one of the largest suppliers in the world of all manner of military goods, serving individual buyers, collectors, and foreign armies from an enormous store at 501 Broadway in New York City. The family conquered every possible market, even selling old uniforms to theater organizations as costumes (including costumes for Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show).

Bannerman’s Catalogue and Customers

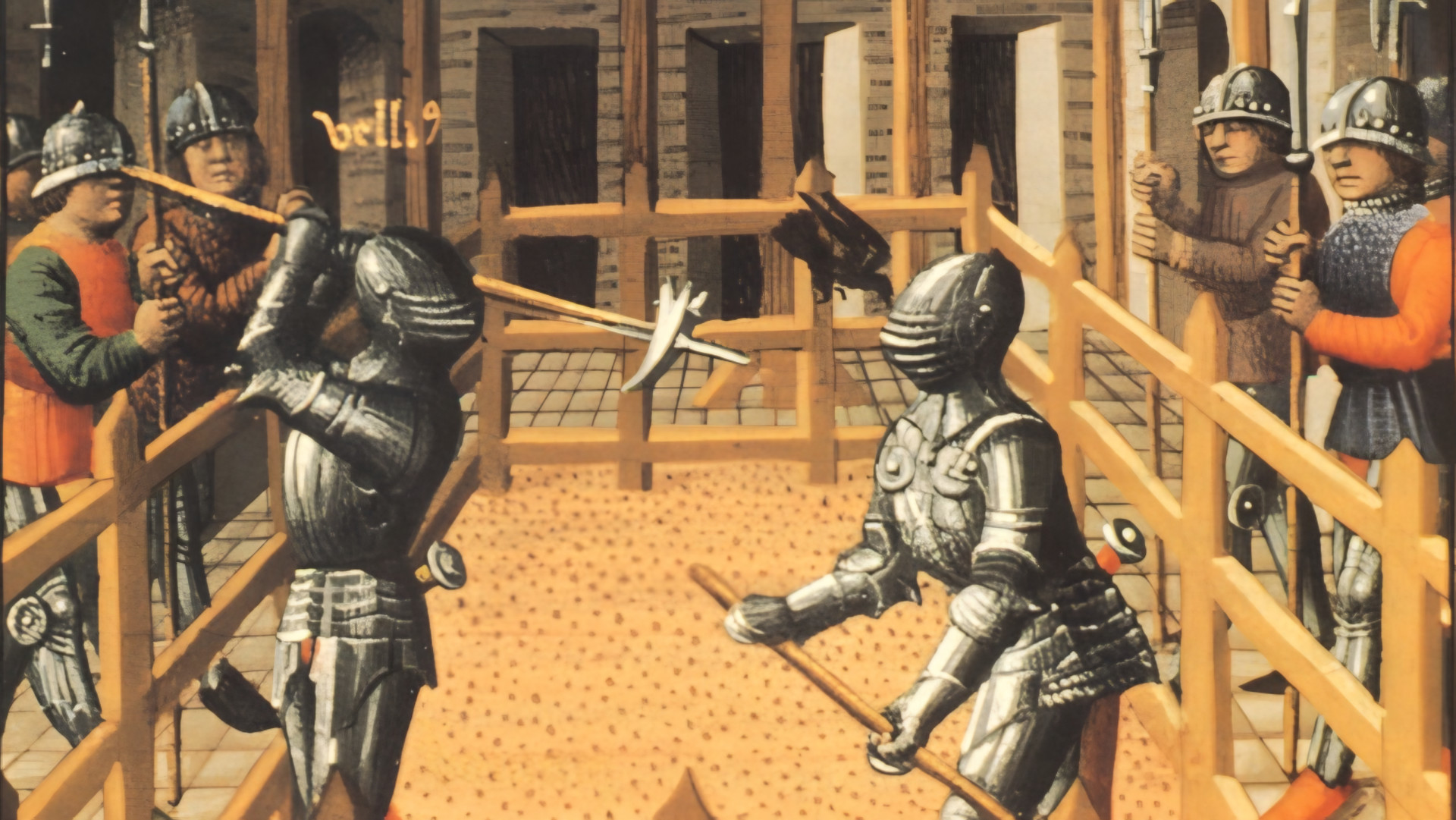

Many years after the Civil War, they were still able to supply original Union uniforms in pristine condition in their original packaging. Many of the commemorative cannons displayed in small towns across the country were supplied by the Bannermans, and they even supplied suits of armor displayed in museums and personal collections around the world.

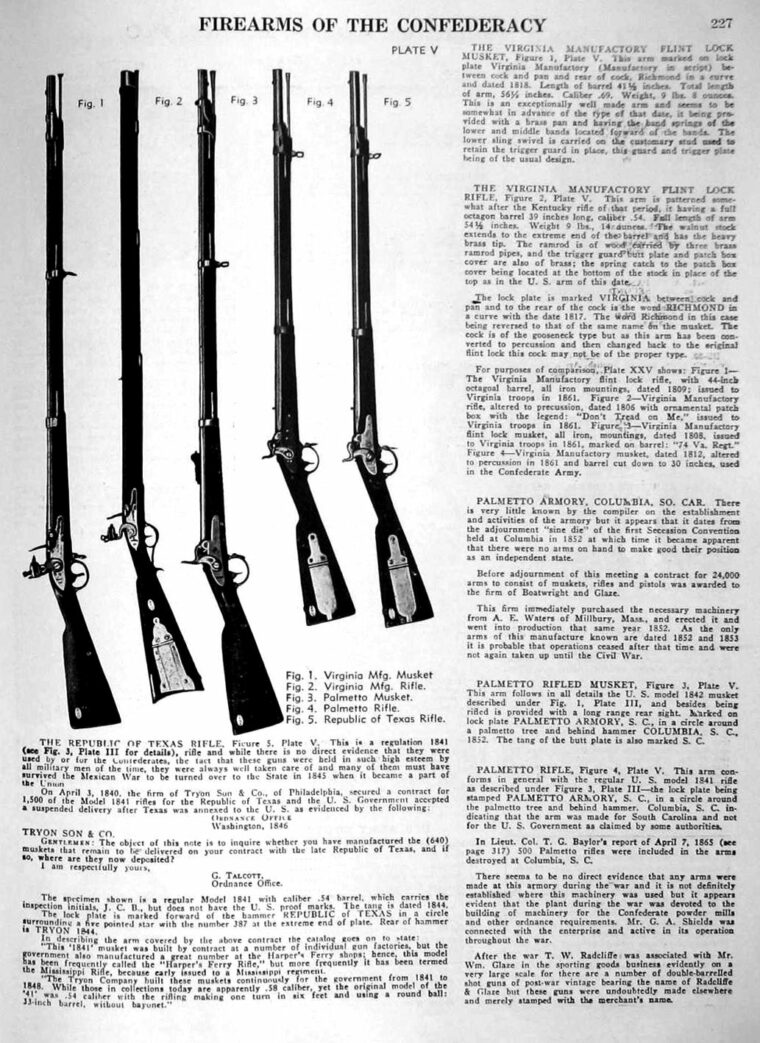

Any type of war goods that an individual might want could be found at Bannerman’s, from ancient crossbows to Civil War muskets, Filipino bolos and barongs, and tribal war shields. The wants of boys and young men were given special attention, and Bannerman’s advertised its catalog in popular boys’ and outdoor magazines of the day. Although Bannerman’s never sold live weapons to minors, a boy could buy any war decorations he might want for his bedroom wall or military-style camping equipment from the 350-page catalogue. The fully detailed catalogue, published from 1880 to the 1960s, is still considered a valuable reference for military supplies. It can even be found in some library systems around the United States.

Bannerman never revealed his largest arms customers, and although he claimed to have never knowingly sold arms to buyers of questionable origin, some of his weapons were said to have inadvertently ended up in the hands of “revolutionists” around the world. Some observers claimed that they saw Bannerman’s weapons being used by insurgents in Panama during their struggle to gain independence from Colombia.

At the onset of World War I, one of Bannerman’s employees, an Austrian immigrant named Charles Kovac, was arrested on charges of spying, casting a large shadow of suspicion on Bannerman’s business. Soldiers were stationed on Bannerman Island for precautionary purposes and made an extensive search of the grounds. Machine guns mounted in the tower of the castle aroused suspicion, but Bannerman claimed that they had only been used to salute passing steamboats. Bannerman sent an angry letter to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, voicing his objections to the island’s occupation and noting his reputation as a true American patriot. As for Kovac, he was subject to deportation, but eventually was paroled and had his work activities on the island severely restricted.

A “Museum of Lost Arts”

Frank Bannerman died in 1918 at the age of 68 from overwork, according to a New York Times obituary, but many believed that the occupation of the island and the suspicion surrounding his name and business had seriously compromised his health. He had also been involved in a large, ambitious war relief effort to Belgium at the time, which may have contributed to his downward turn. The island continued to be used for storage, but all further construction on the castle came to an end. Frank VII and David Bannerman continued to operate the business well into the 1970s out of a massive warehouse on Long Island.

The business eventually began to sell more to collectors than to arms buyers. After the two brothers died, it passed to the control of grandson Charles Bannerman, who ironically had married Jane Campbell and finally ended the clans’ long feud. The family finally sold Bannerman Castle to the State of New York in 1967. A munitions expert was hired to remove any remaining dangerous ordnance, and the city took possession of all the remaining merchandise, some of which was donated to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The state made plans to conduct tours of the castle, but a mysterious fire on August 8, 1969, caused extensive damage. Firefighters quickly rowed to the island to look for anyone who might have been trapped by the blaze, but they could do little to save the castle itself. Stone, cement, and bricks were all that remained of the original structure. Police investigated the possibility of arson, but nothing could be proven. Since that time, the castle has been declared off limits to the public, although the island itself is open for tours from May through October. The fate of the castle is now in the hands of Bannerman Castle Trust, Inc., which is attempting to secure funds for a renovation.

Although he had an exceptional career dealing in weapons of war, Frank Bannerman’s greatest wish was that there would come a day when his weapons were no longer considered necessary and his military surplus store and museum could become known instead as a “Museum of Lost Arts.” He was a great preserver of military history, and experts agree that many of the surviving items dating from the Civil War survive today largely due to Bannerman’s one-man efforts to save them.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments