by Kevin Hymel

The first camps assembled by the Union Army of the Potomac were tent cities, thrown together hastily as new regiments arrived from the free states. They were a disaster. Sanitation was primitive at best, and life-threatening diseases swept through the camps. Soldiers from the remote hinterlands bunked with urbanized city dwellers and quickly discovered epidemic ailments they had never known existed. Childhood diseases such as measles, mumps, chicken pox, and whooping cough claimed many lives. Like any area with a large concentration of aggressive young men, there were also numerous fights, but a strong camaraderie soon built up among the union soldiers sharing the excitement and dangers of war.

[text_ad use_post=”455″]

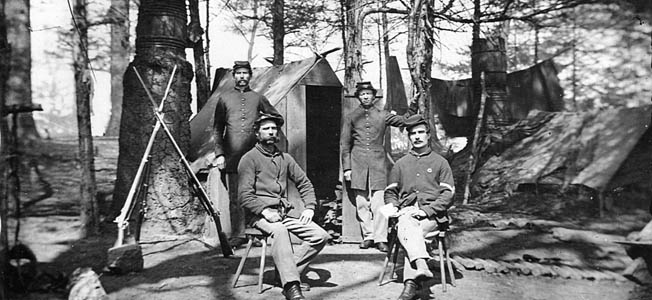

After the First Battle of Manassas, the Army of the Potomac completely reorganized. New, better-designed camps were laid out, and the men’s lives took on an exhausting routine of constant drilling intended to make them more effective soldiers. Crude huts made of logs and mud replaced the drafty tents. Entire forests were felled, and the sound of chopping wood constantly echoed through the air. The men improvised to create more comfortable accommodations. Barrels were used for chimneys, packing crates were broken apart and made into sidewalks to keep out the mud, fences were torn down and used for firewood, and the siding of nearby houses was ripped off and made into furniture.

After the First Battle of Manassas, the Army of the Potomac completely reorganized. New, better-designed camps were laid out, and the men’s lives took on an exhausting routine of constant drilling intended to make them more effective soldiers. Crude huts made of logs and mud replaced the drafty tents. Entire forests were felled, and the sound of chopping wood constantly echoed through the air. The men improvised to create more comfortable accommodations. Barrels were used for chimneys, packing crates were broken apart and made into sidewalks to keep out the mud, fences were torn down and used for firewood, and the siding of nearby houses was ripped off and made into furniture.

When the men weren’t drilling they played cards, shot dice, and ran the bases on crudely laid out baseball diamonds. They bet on boxing matches, cock fights, and even louse races. They smoked and chewed tobacco whenever they could get their hands on the eagerly sought commodity, often trading with their Confederate counterparts across the line during the lull between battles. Like soldiers in every war, they also found their way to rear-echelon brothels and lost themselves in rotgut whiskey, some made from private stills hidden inside huts or purchased from the nearest sutler’s store.

The men left their camps in the spring to begin the campaign season, but retuned after each defeat (and a few victories) at the hands of their Confederate enemy. It was not until the great 1864 offensive under General Ulysses S. Grant that the men left the comfort of their winter camps for good and commenced a hardscrabble bivouac life from Fredericksburg to Petersburg. After the brutal battles in the wilderness, union army soldiers settled into a more squalid life in the muddy trenches south of the Cockade City. They would remain there, locked in a death grip with the enemy, for the next 10 months, until the death of the Confederacy.

The men left their camps in the spring to begin the campaign season, but retuned after each defeat (and a few victories) at the hands of their Confederate enemy. It was not until the great 1864 offensive under General Ulysses S. Grant that the men left the comfort of their winter camps for good and commenced a hardscrabble bivouac life from Fredericksburg to Petersburg. After the brutal battles in the wilderness, union army soldiers settled into a more squalid life in the muddy trenches south of the Cockade City. They would remain there, locked in a death grip with the enemy, for the next 10 months, until the death of the Confederacy.

Camps established by the Army of the Potomac proved that widely divergent soldiers could improvise, adapt, and work together as a team for a common goal. They were primitive yet self-sufficient neighborhoods for fighting men, places their residents would never forget. For every bad memory veterans had of the camps—the filth, the monotonous and wearying drill, and the stomach-wrecking bad food—there were also good memories of brotherhood, shared relaxation, and leisure time away from the battlefront.

Such memories would last a lifetime for the Boys of 1861-1865.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments