By Kevin M. Hymel

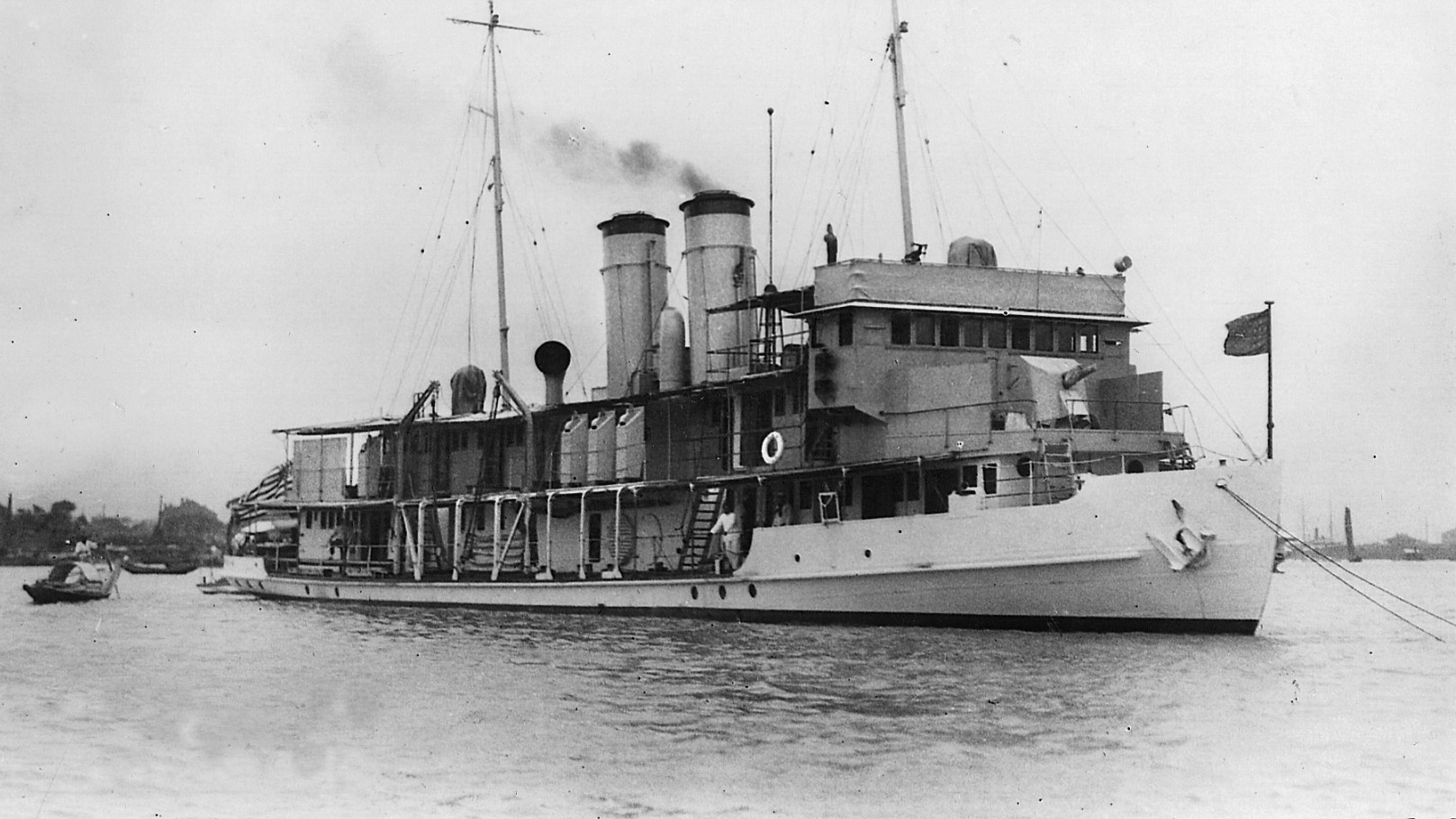

“Only God and the Navy can do anything until we hit the shore,” Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. confided in his diary on the night of July 6, 1943, about the invasion of Sicily, codenamed Operation Husky. But once ashore, he knew what was going to happen: “We will not be stopped.”

Patton and his Seventh U.S. Army had been packed into some 58 ships along the North African coast and headed to Sicily, the island at the end of the Italian boot. He intended, along with British General Bernard Law Montgomery, to capture the island from the Axis powers of Germany and Italy.

One of the sailors who saw Patton on the USS Monrovia, the attack transport which would take him to battle, described Patton’s demeanor: “It was to him not a ship’s deck he stood upon, but a peak of glory.”

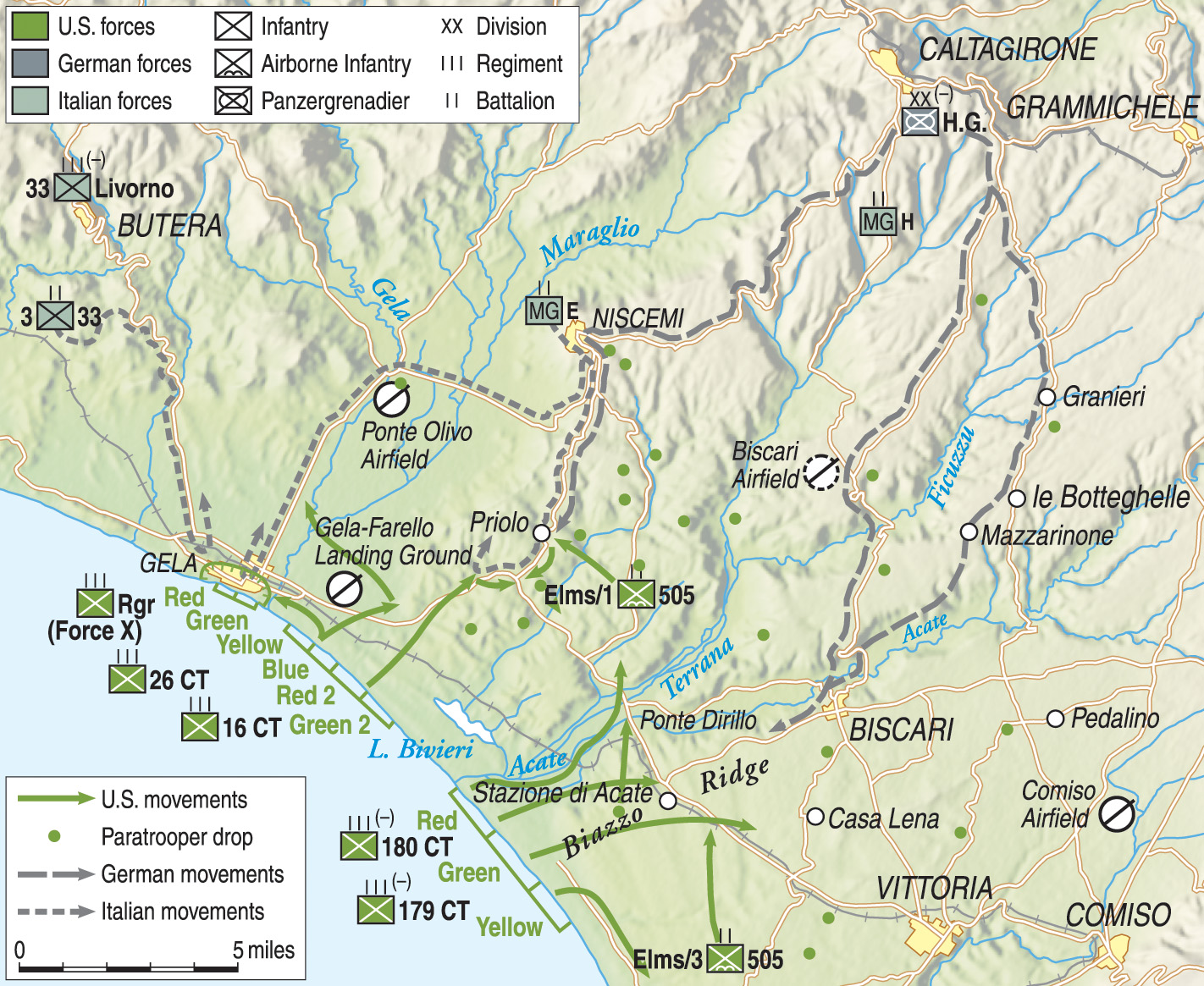

Patton planned to hit Gela Beach, in southern Sicily, while Montgomery would hit southeast Sicily near Syracuse. For his attack, Patton would use an airborne drop followed by a three-division amphibious assault.

Colonel James Gavin’s 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, reinforced by a battalion of Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th—both from Major General Matthew Ridgway’s 82nd Airborne Division—would drop between 11:30 p.m. and midnight of July 9.

Once on the ground, the paratroopers would capture the high ground of Piano Lupo to block enemy forces headed south against the 1st Infantry Division and cover the Ponte Olivio airfield, making it easier for capture by the amphibious forces.

The amphibious landings would hit the beaches at 2:45 a.m. and would be, from north to south: Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division, supported by Army Rangers and some tanks from Maj. Gen. Hugh Gaffey’s 2nd Armored Division around the town of Licata; Maj. Gen. Terry Allen’s 1st Infantry Division, also supported by Rangers, around the town of Gela; and Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s 45th Infantry Division near the town of Scoglitti.

Follow-up forces included the rest of Gaffey’s 2nd Armored Division, Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy’s 9th Infantry Division, and the 4th Moroccan Tabor of Goums—a French battalion commanded by French officers and noncommissioned officers with Berber Goumiers (indigenous Moroccans) as the fighting troops.

Patton hoped to capture the three coastal towns and airfields and link up with the British in three days. D-Day was set for July 10. Combined with Montgomery’s British Eighth Army four-division assault and a single airborne brigade drop on the southeastern side of the island, Operation Husky would be the largest and most dispersed amphibious assault of the war.

Patton was proud of the plan, yet remained humble about the complex operation. When General Sir Harold Alexander asked him if he was satisfied with the plans, Patton clicked his heels, saluted, and responded: “General, I don’t plan—I only obey orders.”

Gavin’s paratroopers spearheaded the invasion. All 3,400 of them had loaded onto 226 C-47 transports at sundown and taken off at 8:30 p.m., July 9, bound for the island of Malta, where they were to turn north for the run to Sicily. But the pilots could not find Malta in the mists and clouds, and were forced to make their best guesses.

The planes that made it to Sicily encountered enemy ground fire. In the confusion, the planes dropped their paratroopers wherever possible, widely dispersing them along the southern coast. Once on the ground, the paratroopers gathered themselves up, searched for comrades, and headed for bridges, high ground, or anywhere they heard gunfire. Some of the pilots gave up on trying to find Sicily, and returned their planes to base with full loads.

Patton stayed up that night on the Monrovia, sitting at a small table in his underwear, reading the Bible by flashlight. At 3:30 a.m., Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, in full battle gear, knocked on his door. Wedemeyer had been sent by Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall to examine the landings and report back to him.

He bid farewell to Patton and thanked him for his hospitality as he prepared to depart with the first assault wave. Patton teared up and told him he appreciated his help. He shook his hand and told him to be very careful. “If anything happens to you,” Patton said, “General Marshall will give me hell.” With that, Patton went to bed for a few hours.

The planes flying over the Monrovia on July 10 did not wake Patton, but a broken davit banging against the ship did. He donned a khaki uniform and leather bomber jacket and made his way to the bridge. The shoreline burned brightly as landing boats churned into the darkness. Searchlights in the distance pierced the night sky as mortars and rockets smashed into targets. Sicily and uncertainty lay ahead. “We may feel anxious,” he reasoned, “but I trust the Italians are scared to death.”

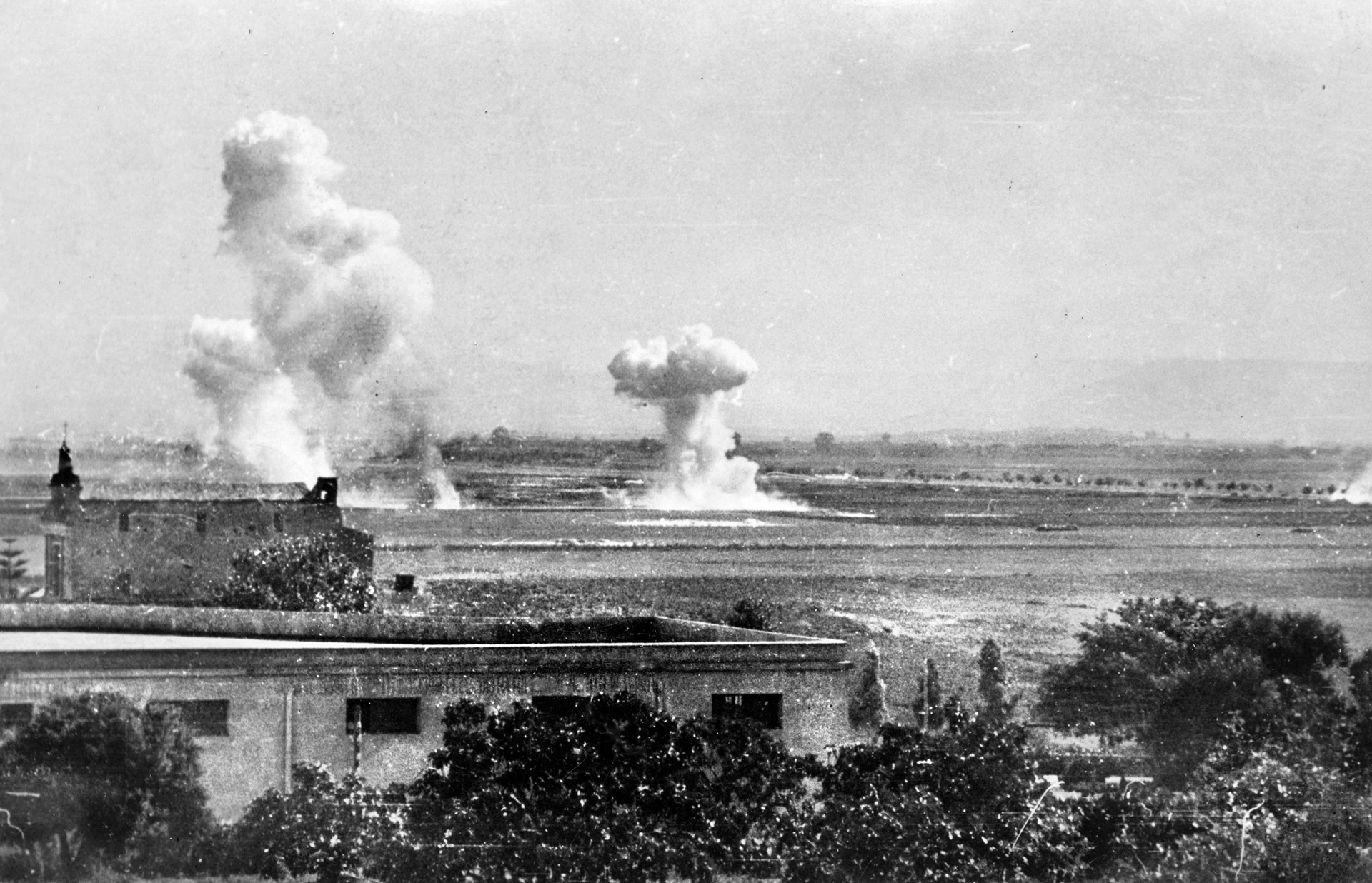

The Luftwaffe bombed the fleet around 5:00 a.m., sinking the destroyer USS Maddox; American fighter planes soon arrived and tangled with the enemy. Despite difficulties caused by the weather and a shifting sandbar off the beach, the 1st and 45th Infantry Divisions landed and captured their objectives before sunrise, the 3rd Infantry Division following soon thereafter. Navy destroyers sailed to within a mile of the beaches, firing on enemy targets. Army Rangers overcame enemy machine-gun nests and pillboxes in Gela so quickly that they ran into Navy covering fire.

At 6:00 a.m., Ranger Lt. Col. William O. Darby radioed Patton that Gela had been taken. Three hours later, Patton heard over the radio that 30 enemy tanks were attacking Allen’s 1st Infantry. The paratroopers had failed to capture the Piano Lupo heights, allowing the Germans a route of attack. The Navy cruiser USS Boise shelled the enemy lines. Patton also wanted fighter planes to strafe the area, but they were not yet over the battlefield.

Throughout the day, Navy anti-aircraft gunners fired wildly into the air at both friend and foe. By the afternoon, Patton ordered Gaffey to land most of his 2nd Armored Division at Gela and await further orders. He then postponed a second airborne drop scheduled for later that day to the following night, so that he could focus on getting his armor ashore.

Communications with troops soon broke down. Only two of his II Corps’ hourly reports reached the Monrovia. Much of the communication equipment was insufficiently waterproofed for the rough weather. While communications would improve, Patton initially relied on messengers going from ship to shore during his opening moves on Gela.

Before the sun went down, the Luftwaffe attacked again, this time sinking an empty Landing Ship, Tank (LST). But the news of the day was mostly positive. The beaches had been taken, objectives had been secured, casualties were low, and Patton’s men had captured more than 1,000 prisoners. There was no word from the paratroopers except from one unit that had linked up with the 1st Infantry.

Patton was so busy coordinating armor, naval, and air support that he never left the Monrovia. “I feel like a cur,” he lamented in his diary, “but I probably did better here.”

That night the Luftwaffe returned a third time. A series of bombs exploded in the water near the Monrovia as Patton entered his cabin. “Let’s get off this damn ship the first thing in the morning,” he told his staff. Another succession of bombs burst nearby. “If this thing is still afloat.” With that, he went to bed.

The next morning, with Luftwaffe bombs still falling around his ship, Patton put on a khaki uniform with puffy, jodhpur trousers and polished cavalry boots, strapped on his Colt revolver, his binoculars, and camera, and grabbed his riding crop. To get more troops onto the beach, he ordered the 82nd Airborne’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment to drop behind the 1st Division’s zone. He then warned his principal commanders that paratroopers would jump about 11:30 that night.

Patton boarded his landing craft with his staff and Ridgway for the half-hour trip to the beach, where he waded ashore, chomping on a cigar. Equipment cluttered the beach as soldiers and seamen wrestled to free beached landing craft. Patton could hear machine-gun and heavy-weapons fire, and saw a row of dead soldiers, attesting to the previous day’s intense fighting.

Geysers from enemy shells erupted in the water and artillery exploded on the beach, impeding the unloading operations and killing civilians. “It’s all right, Hap,” Patton told Colonel Hobart “Hap” Gay, his chief of staff. “The bastards can’t hit us on account of the defilade afforded by the town.”

At the sight of Patton, some men climbed out of their foxholes and charged across the dunes at the Germans, prompting a reporter to write, “I saw, for the first time, just how a brave general can turn the tide of battle by sheer leadership.”

Ridgway took off on foot to find his paratroopers while Patton waited for his vehicle to be de-waterproofed. While he waited, an African-American soldier greeted him and reminded him that they first met when Patton was a lieutenant at Fort Riley, Kansas. The soldier had gone absent without leave (AWOL) just to take part in the invasion.

Patton then climbed the stairs of an apartment from which he could see Italian soldiers advancing across open ground towards Gela. “Can I help you sir?” asked a young naval ensign who was busy directing fire from the USS Savanna. “Sure, if you can connect with your Goddamn Navy, tell them for God’s sake to drop some shellfire on that road.”

The ensign went back to work as Patton grabbed his field glasses and stepped out onto the veranda, where German and Italian soldiers fired at him, forcing the ensign to temporarily evacuate the room.

American naval and mortar fire, combined with two captured Italian artillery pieces and the Rangers’ stout defense, repelled the Axis attack. As the fighting died down, Patton looked down to see a group of American MPs marching a handful of slovenly looking Italian prisoners to the rear. “Make it double time!” He shouted from his perch. “Kick ‘em in the ass! Make it double-time!” The men broke into a trot.

When Patton noticed a Ranger captain with his chin strap dangling, he pointed it out, and the officer quickly buckled it. Before he departed, he implored the captain: “Kill every one of the Goddamn bastards.”

Patton and Darby returned to Darby’s headquarters. As they spoke, two German artillery rounds punched a hole in the building across the street, injuring some civilians. “I have never heard so much screaming,” Patton recalled.

He contacted the naval commander responsible for the landing force and ordered his tank reserves to land immediately, but the naval officer refused, explaining he needed orders from Admiral Kent Hewitt. Patton eventually reached Hewitt and secured permission, but the delay caused confusion and stress.

His need for armor was finally satisfied when 10 tanks arrived from Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division in Licata, some 20 miles away; Patton ordered the tankers to pursue the retreating enemy. He then ordered a pontoon causeway rammed over a series of sandbars, allowing more tanks to race ashore. The rest of the reserve force finally arrived once an LST captain forced his own way over several sandbars. Patton directed the tanks to close the gap between the 1st Infantry and the Rangers.

The enemy attack had almost achieved success, pressing their tanks within 2,000 yards of the beach. So close was the fighting that the ships had to stop shelling, for fear of killing Americans. The Italians and Germans had punched holes in both the 1st Infantry and 82nd Airborne lines but were finally halted at Allen’s last defensive lines around noon. The attack had cost the Germans heavily. Ten tanks lay in smoking ruins.

Once the Germans realized they could not push the Americans into the sea, they withdrew, giving the Navy even more targets. Shells rained down on the retreating enemy. By the end of the day, the Germans had lost one-third of their tanks and some 600 men; Darby counted 500 Italian prisoners. When the Americans began feeding the prisoners, Patton put a stop to it, telling the men that rations would be limited until more supplies arrived.

During the fight for Gela, some local children, chased by adults, had dashed to the enemy lines and began climbing on their weapons, preventing the Americans from returning fire.

While planning the campaign, higher headquarters had asked Patton how many military government officers he wanted. He responded, “Not a Goddamn one of those civilian sissies!” Now he radioed a request to immediately send 25 MPs and 25 military government officers competent in handling children. He also radioed for air support to bomb the advancing tanks, but the planes did not arrive until five hours after the action.

Before noon, during the fighting, the Italians had intercepted a message from Patton ordering his troops on the beach to bury their equipment and to be ready to re-embark. While several Italian officers after the war attested to seeing the message, several people who were with Patton that day had no recollection of him sending any such communique.

“I am quite certain Patton did not personally send the message,” explained British Colonel Robert Henriques, “but it is quite likely that someone, either in 1st Division or Seventh Army Headquarters, may have sent it when the battle was at its height.” Allen did not recall Patton making the decision either: “At no time during his visit did General Patton ever make any mention whatsoever of any re-embarkation plans for the 1st Infantry Division or of any other unit in the U.S. Seventh Army.”

After briefly meeting with Brig. Gen. Teddy Roosevelt, Allen’s assistant division commander, Patton went to find Gaffey and Allen. Meanwhile, 14 German bombers roared in and strafed the area. Nearby anti-aircraft batteries opened up, and shrapnel rained down on the convoy, one piece of shrapnel landing 10 yards from Patton. Two enemy aircraft were shot down.

At Allen’s headquarters, Patton declared his displeasure that the Ponte Olivo airfield—Allen’s objective for the day—remained in enemy hands. Allen reassured him that the day was not over and that he was planning a night attack, “Come hell or high water.” Mollified yet skeptical, Patton departed.

Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, the II Corps commander and Allen’s direct superior, would later angrily confront Patton about the attack on the airfield. He had specifically ordered the attacking unit to hold fast until a pocket of German resistance had been eliminated. Patton’s order to Allen directly contradicted Bradley’s order, thereby violating the chain of command.

Worse, Patton had neglected to inform him about it. Patton later apologized, but Bradley still considered Patton’s move reckless. Bradley’s poor health may have contributed to his sour mood. On the journey from Tunisia, he had undergone hemorrhoid surgery and had to use a flotation device as a pillow when driving around Sicily’s rough terrain.

On the way back to Gela, Patton marveled that he could drive parallel to the front without coming under fire. While it made him feel lonely, it still boosted his confidence: “It is good for self-esteem,” he later wrote. Looking out to sea, he saw the Liberty ship Robert Rowan explode and split in two from a Luftwaffe attack.

Upon reaching the beach, Patton noticed some soldiers digging a foxhole between two huge stacks of bombs and high-explosive shells. “I told them if they wanted to save the Graves Registration burials, that was a fine thing to do but otherwise they better dig somewhere else.” Just then, two enemy bombers strafed the beach, and the men jumped into their foxhole. The bombers circled and came in for another run.

As Patton watched, men unloading landing craft picked up weapons and returned fire. Naval gunfire helped break up the attack. The whole time, Patton strode up and down the beach, ignoring the strafing and barking orders. When a panicked signal officer destroyed a box of signal equipment, Patton ordered him arrested. When he later learned that the officer had been ordered to do so rather than have it fall into enemy hands, he had the man released.

Patton made it back to the Monrovia soaking wet from the turbulent waves. Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, one of Eisenhower’s deputies, was both happy to see him alive and worried for his health. He thought Patton stood up well under the terrific strain of command. “I would be more irritable than he is,” Lucas later wrote.

After seeing the Luftwaffe’s dominance over the battlefield, the accuracy of anti-aircraft weapons, and the Navy’s willingness to fire at anything in the air, Patton cancelled the second airdrop. Unfortunately, the Monrovia’s radios could not reach Ridgway’s headquarters.

Worsening matters, the Luftwaffe attacked the fleet around 10:00 p.m., an hour and a half before the 504th was scheduled to fly over. Allied and enemy fighter planes crisscrossed the night sky, dogfighting while dodging anti-aircraft fire from the ships and on the beach. Before he went to bed, Patton penned in his diary, “Am terribly worried.”

Patton’s apprehension proved prescient. Although the 504th flew into peaceful skies above Sicily, tension and anxiety gripped the men on the ground and on ships. The first group of paratroopers landed without incident. The second group drew fire from a single machine gun. Soon, numerous anti-aircraft guns on land and sea opened fire. Six aircraft crashed before their paratroopers had a chance to jump.

Out of 144 planes, 23 never returned and 37 were badly damaged. Eight planes returned to North Africa without having dispatched their loads. The 504th lost 229 men—81 dead, 132 wounded, and 16 missing, all at the hands of their fellow countrymen. It had been a disaster.

The next morning, July 12, Eisenhower visited Patton onboard the Monrovia, where Patton proudly showed him a map of Seventh Army’s progress. All his divisions save Allen’s 1st, which had blunted the Axis attack, had advanced beyond their objectives, while Middleton’s 45th Infantry Division was expected to meet up with a Canadian division at any moment.

In fact, the 1st Infantry may have again saved the beachhead. At midnight, Allen had launched his promised attack, supported by artillery and naval gunfire. The Germans, preparing to attack at dawn, were caught completely by surprise as Allen’s division rolled up their lines and captured Ponte Olivio airfield.

Despite the rosy news, Eisenhower fumed. He scolded Patton about his progress reports, which did not adequately address the help needed, particularly in terms of air cover. Eisenhower did not realize communiqués were running seven hours behind, nor did he know yet about the airdrop disaster. His lecturing done, Eisenhower and his party headed to his launch, escorted by Patton. As Eisenhower motored away, reporter John Gunther, who was with Eisenhower, noticed Patton standing on deck, “looking like a Roman emperor carved in brown stone.”

The meeting had left Patton embittered. Lucas, who did not hear Eisenhower’s words, commented, “He must have given Patton hell because George was much upset.” Patton agreed: “It is most upsetting to get only piddling criticism when one knows one has done a good job.” Navy Captain Harry C. Butcher, Eisenhower’s naval aide, later summed up the tense meeting in his diary: “Ike had stepped on him pretty hard.”

Patton resumed fighting his army from onboard the Monrovia until he departed the ship for good later that afternoon. He headed ashore aboard a landing craft while enemy fighter planes strafed the area; two were shot down. On shore, as he had done the day before, he checked in with the Rangers and was pleased to learn that they had captured 250 Italians.

He had reason to be proud. The Gela beaches had been taken, and all the American assaults had been successful. Patton then went to his headquarters, which his staff had established in the middle of town in an eight-room house with a backyard patio. It had been owned by a doctor who fled so quickly there were still toothbrushes in the bathroom.

Patton’s first order was for his staff to clean themselves up. Most had been unable to shave in the pitching seas. They had, almost to a man, lost all their equipment when their landing craft disgorged them in deep water and heavy surf, and they had failed to dig latrines for fear of hitting a landmine.

As naval shells rumbled over the house, Patton tried to organize his units. He plugged gaps in the line and sent lost units to their commanders. Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes, Patton’s deputy commander, called from Truscott’s headquarters, whose division had spread out after several running battles with the enemy, and offered that Truscott could attack Agrigento, on the west coast, or Caltanissetta, directly north, but Patton refused to approve either attack until he heard from Alexander.

But before Patton could contact his British commander, he clashed with his British peer. A British lieutenant showed up at Patton’s headquarters carrying a suitcase tied with a string. His presence infuriated Patton, who had earlier sent a liaison team consisting of a colonel, a major, and a communications section in two halftracks to Montgomery’s headquarters. In exchange, Montgomery had sent a single lieutenant. Patton sent the officer back to Montgomery, with a note explaining that he could not permit boys in his headquarters.

Instead, Patton requested Colonel Robert Henriques, with whom he had worked well in Morocco. Henriques arrived and summed up Patton’s successful attack: “The Seventh Army plan was straightforward, simple, and as ambitious as circumstances of craft and shipping allowed. Within the limits of the Allied plan, General Patton had few, if any, alternatives to the course which he adopted.”

That night, after a dinner of canned cheese and champagne, Patton discovered his bed filled with bedbugs, forcing him to sleep in his bedding roll on the ground.

The next morning, July 13, Patton went to a 1st Infantry Division forward operating post, stomped up to the balcony, and demanded to see what was going on. Just then an artillery shell hit near the building and some forward observers ducked for cover. He bawled the men out for cowering and threatened to arrest them. He then left the building to watch supply ships arriving on the beach below.

Colonel James Gavin, the commander of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, who had been fighting nonstop since parachuting in on D-Day, rolled up in a jeep. Patton whipped out his flask. “Gavin, you look like you need a drink. Have one.” To Gavin, Patton exuded confidence, and he was proud to see an army commander “in the midst of things.”

When a German Messerschmitt Me 109 strafed the beach, Major Alexander Stiller, one of Patton’s staffers, opened up with a .50-caliber machine gun, knocking it out of the sky. Patton immediately awarded him a Silver Star for setting an example, encouraging other soldiers and—most important—engaging the enemy and not diving into the sand.

Patton had successfully landed his army in Sicily and could now focus on what to do next. While his job was to head northeast and protect Montgomery’s left flank, he had other ideas. If he could capture a port, he could supply himself rather than relying on supplies from the British. And if he could do that, he could drive his army north and capture the city of Palermo, basically cutting the island in half. But first he needed a port, and Patton eyed Agrigento, only 27 miles away.

This article is excerpted from Kevin Hymel’s latest book, Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 1: November 1942—July 1944, published by University of Missouri Press. Volume 1 follows General Patton from the beaches of Morocco to the battlefields of Normandy, the day before his Third Army became active on the Continent. Mr. Hymel has served as this magazine’s research director and is a frequent contributor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments