By Alexander Lovelace

The October light was beginning to fade as the U.S. Army limousine sped along the autobahn in the American Zone of Occupied Germany. Inside rode the supreme commander of the Allied armies in Europe, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, accompanied by his son, Lieutenant John S.D. Eisenhower. The trip was not unusual since occupation duty in 1945 allowed ample time for the supreme commander to see his son; yet later John would remember his father’s mood that evening as “pensive.” Finally, Ike turned to John and said sadly, “I had to relieve General Patton from the Third Army today.”

The Controversy That Brought Down Patton

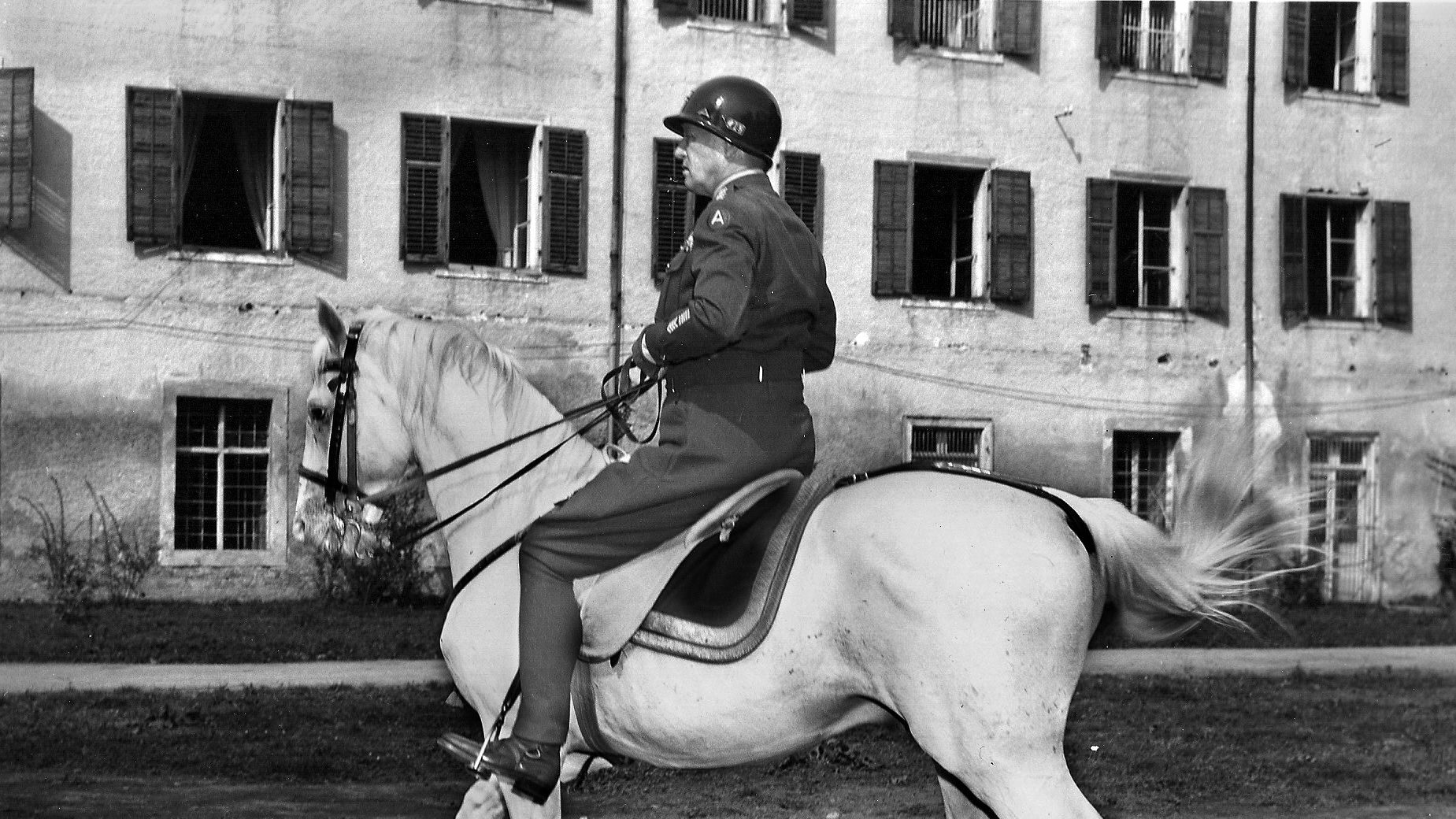

George Patton, the brilliant and outspoken commander of the Third Army, who had liberated more territory than any other American general in Europe, had finally gotten himself into a controversy his old friend Eisenhower was unwilling to tolerate. When the war ended, Patton had been put in charge of occupied Bavaria, making him responsible for implementing the U.S. policy of rebuilding the country and purging the institutions of anyone who had been a member of the Nazi Party. However, under Hitler most Germans had been compelled to join the party to keep their jobs. Realizing this, Patton concluded that Germany could not be rebuilt without using former low-level Nazis.

The greatest threat to Germany, Patton believed, was Soviet expansionism, not a revival of Nazism. He reasoned that the sooner Germany was rebuilt, the sooner it could act as a U.S. ally against the Soviets. However, in the middle of 1945 the Cold War had not yet fully begun, and Patton’s opinions were ahead of the times since many Americans, including Eisenhower, hoped that the Soviet-American wartime alliance would continue.

At a press conference near the end of September, Patton, goaded by reporters, stated, “The Nazis are just like the Republicans and Democrats.” At least that is what appeared in the next day’s headlines. During the war, Eisenhower had saved his old friend when he was attacked by the media for slapping two hospitalized soldiers and again when he made anti-Soviet remarks, but now that the war was over Eisenhower saw little point of keeping Patton in a job he was clearly unsuited to hold. As Ike mused to John that October evening, “I’m not moving George for what he’s done—just for what he’s going to do next.”

Eisenhower’s solution was to transfer Patton to the Fifteenth Army, which was then documenting the history of the European war, and where John was serving as a staff officer. Sandwiched between the momentous events of Patton’s firing from the Third Army and his death two months later, the time he spent at Fifteenth Army is usually glossed over by historians.

Since the Fifteenth Army left few postwar primary sources, historians have found it difficult to investigate this part of the general’s life, which, at first glance, seems of little importance. This is unfortunate since not only was Patton’s time at the Fifteenth Army a success, but it also gave him a chance to influence how history would remember him.

Patton’s Transfer to the Fifteenth Army

Patton arrived at the Fifteenth Army on October 8, feeling the hurt and anger only friendship can cause. He was convinced that Eisenhower had sacrificed him for political expediency and a desire to please future American voters. Patton wrote his wife on October 15, “Ike is bitten with the presidential bug and is also yellow.” Yet Patton was certain that his actions in Bavaria and his fear of the Soviets would soon be vindicated. Until then, his new assignment gave him time to plot his next move.

The Fifteenth Army was very different from Patton’s previous command. Most of the troops had been shipped back to the United States, leaving only the headquarters staff and housekeeping units. A report given to Patton at the time of his arrival gives the strength of the army at 367 officers and 3,090 enlisted men, with two-thirds of the officers working directly at the headquarters. At that time, the Fifteenth Army’s assignment centered around the general board, which comprised the Army’s headquarter staff, tasked with researching and writing reports on how different sections of the U.S. Army had performed during World War II.

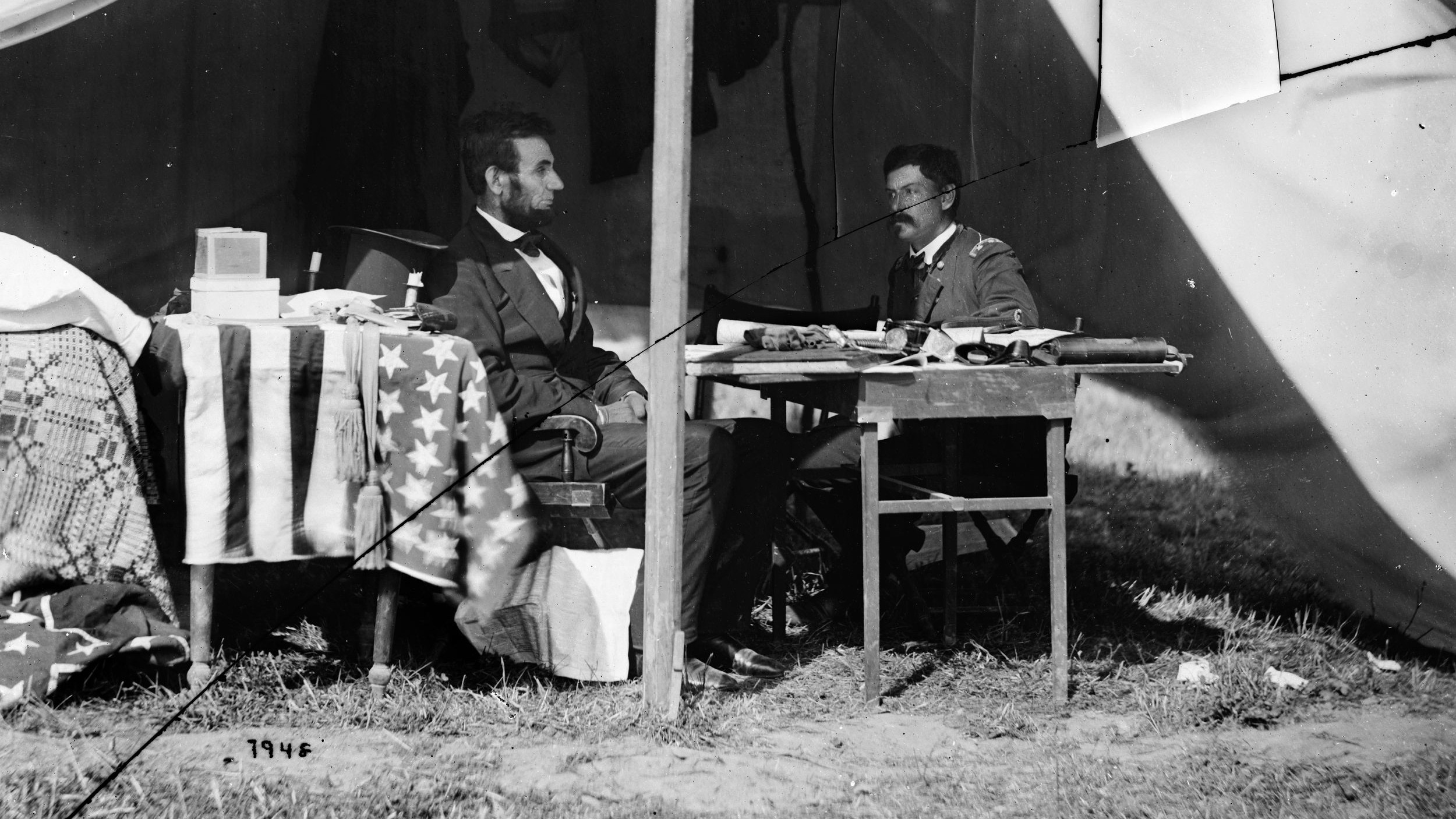

Patton, as the new commander, would act as the board’s president. Eisenhower wrote later that he had established the general board at the end of the war so “the War Department might have permanently available all the facts … and the opinions of the men most experienced in the actual business of fighting….” It was hoped that these reports would provide sources for historians and lessons for the War Department on future conflicts. Instead of an army, Patton was really taking command of a regiment of historians and their support staff.

“Pleasant Indeed”

Before Patton’s arrival, service on the general board was, in John Eisenhower’s words, “pleasant indeed.” The headquarters was located at Bad Nauheim, Germany, which had been a resort town before the war. Since their mission was primarily academic, there was little urgency among the staff to finish the reports. It was with trepidation that they awaited the arrival of their new commander, who had built his controversial reputation on hard work and strict discipline.

Patton’s arrival at the Fifteenth Army was both dramatic and reassuring. According to his diary, he arrived early and spent the day reviewing the various historical sections. At lunch Patton, immaculately dressed, strode into the officer’s mess hall and grimily looked around. The officers shot to attention, Patton’s stern appearance confirming their worst fears. As Patton’s former aide Robert Allen wrote later, the general and his new staff eyed each other warily for a few moments, then Patton relaxed and said, “There are occasions when I can truthfully say that I am not as much of a son of a bitch as I may think I am. This is one of them.”

The officers roared with laughter. The general then assured his new staff that he would not make any changes to how the headquarters was managed for at least one week. John Eisenhower recalled that later in the evening there was a reception, which Patton opened by announcing, “I have been here and studied your work today.” Then, raising his high-pitched voice, continued, “I have been shocked,” dramatic pause, “by the excellence of your work.”

Writing Down the War

However, one change that Patton did institute in the first week was to speed up production. He had received a report dated September 30, 1945, which showed that after three months of work only 10 out of 137 reports were more than 50 percent finished. Patton announced that he wanted to be home by March and all of the reports must be finished by then, which caused, as John Eisenhower remembered, everyone to begin working frantically. Privately, Patton told United Press correspondent John McDermott that he planned to have the general board’s mission finished by January 31, 1946. He had good reason to hurry. At that time, the Army was being reorganized to fit the postwar world. The general board’s reports had the potential to influence how the new military would function.

According to his diary, Patton informed the heads of the historical sections, “The best is the enemy of the good, by which I mean that something now will be better than perfection when it is too late to have any influence.”

Many of the Fifteenth Army officers, who began to work furiously to meet their new commander’s timetable, must have wondered why Patton was any more qualified to write history than he had been to run Bavaria. However, as Patton explained to John McDermott, the job was “right down my alley because I have been a student of war since I was about seven years old. Up until that time I studied the Navy.”

Indeed, under his carefully cultivated brash warrior image, Patton’s study of history went something beyond that of the gifted amateur. His use of history was so central to his actions on the battlefield it has been the subject of numerous articles and one excellent book by Roger Nye titled The Patton Mind. Since childhood, Patton had loved reading ancient and modern military history. In later life, Patton authored numerous articles on warfare, which drew heavily on historical examples to answer current problems. As historian Carlo D’Este concludes in an essay on Patton’s reading habits, the general “was a complete student of history who should be remembered as one of the few American commanders prepared to fight the German army in World War II.”

Preserving His Legacy

At first, life as a historian seemed to agree with Patton. He told McDermott, that the general board had “a great historical and educational value…. I think anyone who is fortunate enough to have his name connected with it is very lucky because people will study what he says….”

Nor was Patton shy about using the Fifteenth Army for self-serving ends. Reading The Strategy of the Campaign report, which told of the Allied armies’ liberation of France, John Eisenhower was shocked to find that Patton’s Third Army was mentioned three times more than any other Allied army.

Despite an outward show of enthusiasm for his new job, it did not distract Patton from the anger he felt toward Eisenhower, the media, and all the others he believed were responsible for his removal from the Third Army. He wrote his wife on October 10, describing the general board as “very much like … the old Historical section in Washington. We are writing a lot of stuff which no one will ever read.” He devoted his diary not to his day-to-day work but to castigating his supposed tormentors and worrying about the spread of communism.

Unofficially, Patton was doing a great deal of writing to preserve his reputation for posterity. As historian Ladislas Farago noted, Patton’s “few weeks of ‘moonlighting’ as a historian did no damage to his fame as a fighter.”

Rather, it was a golden opportunity to preserve his legacy in a book that would describe his experience in World War II and convey his philosophy on warfare. The book went through a number of proposed titles including War as I Knew It or, Helpful Hints to Hopeful Heroes, then, War and Peace as I Knew It, and finally, back to War as I Knew It. Patton wrote the book hoping it would redeem his reputation, while sharply criticizing Eisenhower along with other Allied leaders for what he saw as mistakes made during the war, culminating in the ultimate folly of disagreeing with him over de-Nazification and the Soviet menace. War As I Knew It was published after Patton’s death with most of the controversial statements about Eisenhower and other Allied leaders removed by his widow. The book was thus not the political bombshell Patton had hoped but nevertheless became a best seller; it is one of the classics of World War II.

The Fifteenth Army: Patton’s Last Victory

As time passed, Patton grew increasingly restless. He began to travel around Europe accepting awards and seeking out people who agreed with him about the Soviets. He also debated with friends whether he should resign from the Army so he could speak his mind. Robert Allen quotes Patton telling his chief of staff, General Hobart Gay, in December that he intended to leave the service “with a statement that will be remembered a long time.”

On December 5, Patton wrote his wife that he would be home for Christmas and “don’t intend to go back to Europe. If I get a really good job I will stay, otherwise I will retire….” By that point, the mission of the Fifteenth Army was nearing completion well ahead of the March deadline.

Patton would not live to see his fears of the Soviets vindicated by the Cold War. On December 9, Patton was going hunting when his car collided with an Army truck. He was taken to a hospital with a broken neck. The general passed away on December 21, 1945.

Today, the general board and the historical reports it produced are almost totally forgotten. However, the Fifteenth Army was Patton’s last, and least remembered, victory. He had rejuvenated the general board and greatly increased productivity. Three months before his arrival only 10 of 137 reports were even close to completion. Three months after he took command all 137 reports were finished.

The Fifteenth Army also gave Patton time to finish War as I Knew It, which embodied his legacy and principles on war and is still available in bookstores. It is one of the ironies of history that Patton’s last victory came not with the sword but with the pen.

Author Alexander Lovelace is a first-time contributor to WWII History. He resides in Pasadena, Maryland.

General Patton was a great man. We sure could use some like him these days.

Correct. Patton was always quite perceptive though a bit too direct for his own good.

History provides the lens to show how correct Patton was concerning the truth about the USSR. So much misery could have been avoided if the US had taken a firmer stance with Stalin.

For Stalin ….. Read Putin.

I can remember reading in a Patton biography almost a footnote about his command of the Fifteenth Army, but I never had any idea what that actually meant.

Now I know!