By Joshua Shepherd

For General Thomas Gage, 1775 was shaping up to be a disastrous year. Gage, who was the supreme British commander in North America, was headquartered in Boston and tasked with the unenviable job of enforcing a blockade of the town’s harbor. Worse yet, relations with the provincial assemblies in all 13 American colonies were rapidly degenerating. Indeed, tensions were so high in Massachusetts that an armed clash seemed inevitable.

Affairs were little better on the frontier. Gage began receiving intelligence reports early in the year from the British post at Ticonderoga in northern New York. Settlers who lived near the fort reported a series of bizarre encounters with roaming backwoodsmen. The persistent newcomers were pushy, stole food, and asked a lot of questions regarding the condition of the fort, the size of the garrison, and the number of sentries guarding each gate.

Alarmed by such suspicious interest in His Majesty’s post at Ticonderoga, Gage warned the commander of the fort, Captain William Delaplace, to be wary. “The intelligence you sent me will no doubt have put you on your guard,” wrote Gage. The greatest threat, he believed, came from lawless frontiersmen from the New Hampshire Grants. “There are a number of armed vagabonds going frequently about the lakes, and if they meet you off your guard may form a scheme to seize your ammunition which they are in want of,” he wrote.

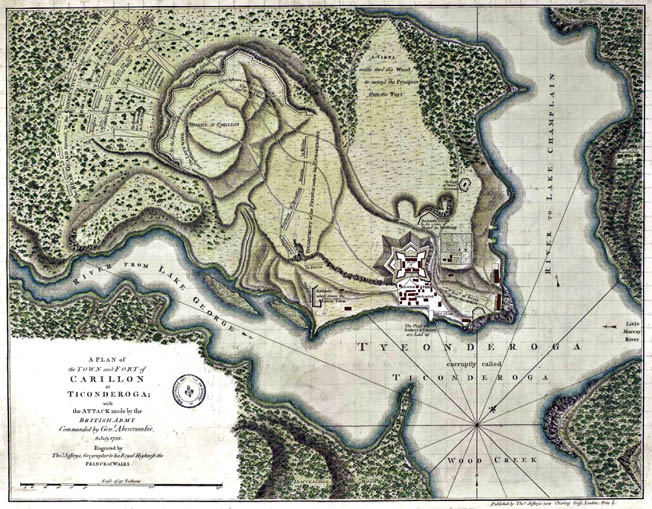

The posts that sparked Gage’s concern were the British installations at Ticonderoga and Crown Point. These forts commanded the most strategically vital body of water in North America: Lake Champlain. Although the lake straddled vital trade routes, its greatest value was military. The locale had truly been at the crossroads of empire since the 16th century. To the north, Champlain flowed into the mouth of the Richelieu River, affording direct access to the French citadels of Montreal and Quebec in the heart of Canada. The head of the lake offered two options for southbound travelers, ones via Lake George and the other via Wood Creek. Both routes required a short portage to the Hudson River, which flowed directly to the English strongholds at Albany and New York City.

Not surprisingly, Lake Champlain was at the epicenter of fighting during the French and Indian War. In the deadly race to control the water route that commanded the continent, France initially took a commanding lead. In the 1730s, French troops built an impressive citadel at Crown Point, a jutting peninsula that commands the narrows of Lake Champlain. Although the installation boasted masonry walls 12 feet thick, it was a less than flattering testament to the longevity of French engineering. Two decades later the fort was a crumbling shell, and French troops, desperate to block an English advance toward Canada, opted to construct another fort just 15 miles south of Crown Point.

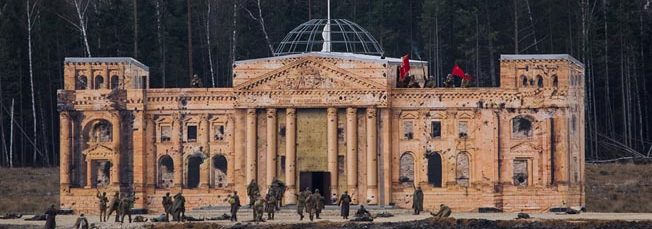

The new installation, christened Fort Carillon, was situated at Ticonderoga. To the Native Americans, the locale was aptly known as “the meeting of the waters,” a strategically placed narrows of the La Chute River that joins Lake George and Lake Champlain. Ticonderoga was likewise fortified with a masonry structure intended to withstand a conventional European siege. In their time, the forts at Crown Point and Ticonderoga were the crown jewels of France’s North American empire, but by 1759 they had fallen into British hands. The following year, British forces succeeded in mopping up the last French resistance in Canada.

With the advent of uncontested British dominance in North America, the formerly vital installations on Lake Champlain largely lost their strategic value. No longer considered powerful bul- warks on an imperial frontier, Ticonderoga and Crown Point were regarded as little more than obscure backwater posts; nevertheless, British troops continued to garrison both forts. Crown Point was assigned a token detachment while the impressive fortress at Ticonderoga, which was bristling with captured French artillery, was manned by a larger force. The Redcoats on Lake Champlain, though, were by no means considered the elite of the British army. Drawn from the 26th Regiment of Foot, which was based out of Canada, the detached companies that served at Ticonderoga were idle garrison troops who were often convalescents unfit for other duties.

Despite a continued British military presence, the forts suffered from a decade of peacetime neglect. At Crown Point, an atmosphere of lax discipline contributed to disaster. On April 21, 1773, two soldiers’ wives who were boiling soap let their fire get out of hand. The timber fortress, which had been painted with tar as a preservative, ignited, causing a major fire. The ensuing conflagration almost completely destroyed the fortress.

The charred remnants of Crown Point took a backseat to a rapidly degenerating political crisis in the spring of 1773. In the face of a looming colonial rebellion in the 13 colonies, Gage sailed for England to assist in formulating an official government response to a state of virtual insurrection in Massachusetts. Assuming temporary command in his absence was Maj. Gen. Frederick Haldimand, a Swiss soldier of fortune who spent a career serving the king of Great Britain. Although Haldimand was confronted with far more weighty matters, the nettlesome question of the decrepit posts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point fell to him.

The following year, British engineer Captain John Montressor was dispatched to northern New York to report on the condition of the forts. Montressor was hardly impressed with what he saw. Due to the fire at Crown Point, that fort had been rendered, in his words, “an amazing useless mass of earth.” To Montressor’s trained eye, Ticonderoga was little better.

Montressor described the outer wall of the fort as badly rotted, and large sections had collapsed. What was left of the log palisade was sadly “leaning to the horizon,” he noted. After studying the situation, Montressor concluded that to maintain a post at Ticonderoga, the old structure would have to be completely razed to make room for a new fort. Rebuilding Ticonderoga simply was not worth it, Montressor said. Crown Point, which was situated at a natural choke point on the Champlain narrows, would be a healthier locale for the troops, as well as a better location for wintering British vessels.

Crown Point also had another advantage over Ticonderoga: it was a virtual blank slate. The fortress had been so wrecked by fire that little demolition work would be necessary before the construction of a new post. Following Montressor’s advice, Haldimand recommended abandoning Ticonderoga because of its dilapidated state and constructing a new fort at Crown Point.

As relations between colonies and mother country continued to degenerate, Haldimand had ulterior motives for his decision. By the spring of 1774 it was becoming increasingly apparent that an armed confrontation with the colonies was a distinct possibility. In a commendable display of strategic foresight, Haldimand proposed using the new construction project as an excuse for a massive military buildup on New England’s back door.

The general suggested transferring two regiments from Canada to Crown Point “under the pretense of rebuilding that Fort, which from its situation … opens an easy access to the back Settlements of the Northern Colonies and may keep them in awe.”

Haldimand’s opinions should have carried greater weight. Throughout the summer of 1774, the British high command, which was clearly occupied with weightier affairs, largely ignored the dilapidated posts on Lake Champlain. The decrepit commissary’s store room at Ticonderoga, which was plagued by rotted timbers, collapsed in August. Gage informed the officers at the fort that he was aware of the bad condition of the post; however, given that Ticonderoga might be abandoned, he ordered that reconstruction efforts “be at as little expense as possible.”

By that autumn, Gage’s superiors in England opted to reject the professional engineering opinions of John Montressor. The British decided that Ticonderoga would undergo extensive repairs and that a new fort would be built at Crown Point. But with the harsh north- ern winter setting in, construction would have to wait until the spring thaw. In March 1775 Gage finally issued orders for work to begin at Crown Point. He hoped that the new post would be a nearly impregnable wilderness stronghold. On a frontier where rebels were sure to have no chance of bringing artillery to bear, Gage recommended that the new fort be built of stone.

But time and fate were working against British plans for strengthening defenses of the Champlain corridor. On the morning of April 19, 1775, a British column out of Boston, which was headed for Patriot arms and munitions in the country hamlet of Concord, ran into trouble. After clashing with local militia on Lexington Common, the Redcoats were badly cut up in a day-long running fight that resulted in 300 British casualties. The fight marked the beginning of armed hostilities in the American Revolutionary War and set in motion a turbulent struggle for the backcountry post of Ticonderoga.

Patriot leadership had been eying the fort for some time. Earlier that year, Massachusetts authorities had commissioned a covert mission to Canada, dispatching Patriot lawyer John Brown to the far north. As part of his report on the mission, Brown strongly recommended an audacious strike for Lake Champlain in the event of war. “The Fort at Ticonderoga must be seized as soon as possible should hostilities be commenced by the King’s troops,” he wrote. Furthermore, Brown added, he had found just the men for the job. In the rugged outer reaches of modern Vermont, Brown had encountered a hard-bitten set of frontiersmen who were more than willing to do the job.

As events would prove, Brown’s observations were correct. On the northern frontier, the arduous nature of pioneering had engendered a rough and ready populace that was accustomed to, and often itching for, a fight. In Vermont, which was then known as the New Hampshire Grants, the situation was exacerbated by conflicting claims to the region. Perched along the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, Vermont was a region dominated by rugged mountains and rugged men. The area had largely been settled by farmers from New Hampshire who had acquired land grants under the auspices of Governor Benning Wentworth. Thriving communities had sprung up in the decades preceding the conflict, but they were by no means years without conflict.

The trouble arose due to an unfortunate territorial dispute between New Hampshire and New York. While New Hampshire granted hun- dreds of thousands of acres to its citizens, the colony of New York was busy doing the same. When claims overlapped and competing authorities vied for taxes, trouble was bound to ensue. The contest was seemingly resolved in 1764 when King George decided the controversy in favor of New York. But New Hampshire per- sisted in selling grants in Vermont, and British authorities procrastinated in the implementation of New York governance.

By 1771 the situation had spiraled out of control. Despite the superficial appearance of legality, New York officials began to encounter more forceful resistance to their authority. Settlers pos- sessing New Hampshire land grants, fearful that their property would eventually be seized by the New Yorkers, formed ad hoc militias to oppose encroachment of their settlements. The ensuing territorial squabbles failed to result in major bloodshed but did lead to a good measure of chaos. New Yorkers, including surveyors, sheriffs, assessors, and common settlers, were subjected to mass resistance and mob violence. Despite being the third most populous colony in North America, New York was largely impotent to enforce its authority east of Lake Champlain.

The triumph of New Hampshire settlers was due in no small part to volunteer militias that began forming in 1771. Composed of farmers, tradesmen, and laborers who were determined to keep their homes and land at all costs, the militias made New York governance all but impossible. One of their key leaders was Ethan Allen, a bull-headed Vermonter with a penchant for tough talk and rash action.

Allen was born in 1738, son to a starchy Connecticut farmer who passed a good deal of his stubbornness on to his son. The younger Allen initially made his living as a farmer, then as an iron monger, and alternately lived in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Notoriously combative over the slightest provocation, Allen occasionally ran afoul of the authorities for petty infractions. By the late 1760s, Allen had pulled up stakes and set out for the New Hampshire Grants. A gifted public speaker and charismatic leader of men, he quickly became a prime spokesman for the beleaguered settlers of Vermont.

But when words gave way to violence over the land dispute in the New Hampshire Grants, Allen proved himself more than capable of exerting force. Allen met in 1771 with other disaffected settlers at the Catamount Tavern in Bennington, an inn and grog shop that functioned as something of a de facto seat of government in the Grants. Allen was instrumental in forming the Green Mountain Boys, the legendary Vermont militia that would enforce its own punishing brand of frontier justice.

In safeguarding the property rights of the Vermonters, Allen quickly established a reputation for impetuous force that was difficult to discern from outright thuggish behavior. Allen and his followers were not above burning the homes of New York settlers, and eventually a small reward was offered for his capture. Allen was little affected by such threats, and at one point issued a contemptuous dismissal to New York officials. “The gods of the valleys are not the gods of the hills,” he wrote. To the frustrated authorities in Albany, Allen and his cohorts would eventually earn the unflattering sobriquet the Bennington Mob.

The unique skills of such men benefited the Patriots when armed conflict broke out with England in April 1775. As soon as hostilities commenced, Patriot leaders began looking into the possibility of a strike against Ticonderoga. Subsequent to the British debacle at Lexington and Concord, heavily outnumbered Redcoats in Boston were placed under siege by swarms of New England militia. The volunteer soldiers carried a motley assortment of small arms but were woefully ill equipped for siege operations. Few artillery pieces were available, and those few possessed by the Patriots were generally smaller fieldpieces unsuitable for conventional siege operations.

A remedy for the woeful lack of artillery would come about largely due to the audacious idea of Benedict Arnold, a particularly scrappy Connecticut militia captain. Arnold was a fiercely self-determined man possessed of driving ambition. Born in Norwich, Connecticut, in 1741, he was initially apprenticed to a druggist at the age of 14. During the French and Indian War, Arnold ran away from his master and enlisted as a private in a company of New York troops and then deserted. By 1760 he had enlisted again and, almost just as quickly, deserted again.

Arnold’s luck, oddly enough, took a turn for the better following the death of his parents. After selling off a good portion of the estate, Arnold moved to New Haven, where he opened up shop as a druggist, bookseller, and merchant. He succeeded remarkably well in his business ventures, eventually trading in commodities and horse flesh in New England, the West Indies, and Canada. It was during his business trips to Canada that Arnold became familiar with Ticonderoga. A keen observer, Arnold could not help but take note of the installation’s decrepit condition.

Arnold had been elected a captain in 1774 in the most prestigious militia outfit in New Haven: the Governor’s Foot Guard. When the news of Lexington and Concord reached New Haven, hesitant town fathers decided that they would not authorize the local militia to march to the aid of Patriot forces. Arnold would have none of it, and demanded that his men be supplied with ammunition from the public stores. When he was refused, an infuriated Arnold thundered that he would assault the magazine and remove the supplies by force. As was his custom, Arnold generally took what he wanted.

Such a penchant for impetuous action would prove highly advantageous in the high-stakes contest for control of Lake Champlain. When Arnold marched his command to Boston, he encountered Colonel Samuel Parsons, who was headed the opposite direction to obtain further recruits. Parsons mentioned the desperate need for artillery, and Arnold immediately recalled the scores of guns that he had seen at Ticonderoga and Crown Point.

When he reached the American lines outside of Boston, Arnold approached the Massachusetts Committee of Safety and outlined a plan to seize the guns. The committee initially demurred and simply forwarded Arnold’s intelligence to New York authorities. But Dr. Joseph Warren, a key Patriot leader who favored bold initiative over bureaucratic inaction, strong-armed other members of the committee into authorizing an expedition without waiting for cooperation from New York.

On May 3, 1775, Arnold was commissioned a colonel and authorized to mount what was described as a secret service. He was tasked with recruiting up to 400 men from the frontier settlements of western New England, reducing the British garrisons at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and removing the desperately needed artillery from both forts.

Arnold succeeded in raising recruits in short order and proceeded to organize affairs in the New Hampshire Grants. But when he reached Stockbridge in western Massachusetts, Arnold was taken aback to learn that another expedition for the reduction of Fort Ticonderoga was already underway; even worse, it was completely out of his control.

Colonel Parsons, after his return to Connecticut, had taken it upon himself to apprise Connecticut authorities of the availability of British guns at Ticonderoga. While Arnold had been organizing his expedition, Connecticut opted to launch its own independent campaign toward Lake Champlain. Command of the Connecticut operation ultimately fell to a man who had already proven he could make a good bit of trouble on the frontier: Ethan Allen.

Outraged at what he considered an encroachment of his authority, Arnold sped ahead to find the Green Mountain Boys and assume personal command of them as well. When he caught up with them at Castleton, the meeting, not surprisingly, did not end cordially. The Green Mountain Boys already had agreed to proceed under Allen’s command when Arnold arrived in a huff. Arnold demanded “command of our people, as he said we had no proper orders,” according to Captain Edward Mott. True to form, the westerners simply brushed him off, informing Arnold in no uncertain terms that they would only serve under their own officers.

Not easily dissuaded, Arnold set out to find Allen personally and assert his authority. When the two stubborn Patriot leaders finally met, a confrontation was inevitable. When Arnold finally found Allen at the rendezvous point on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain, he demanded command of the entire operation. Such last-minute wrangling did not go over very well. Allen naturally rejected the idea in blunt terms. Arnold persisted. The argument escalated until a frustrated Allen finally snapped. “What shall I do with the damned rascal?” he asked his men. “Put him under guard?”

The impasse ostensibly was resolved due to a sudden display of backwoods compromise. One of Allen’s men unexpectedly arrived at a surprisingly simple solution: “Better go side by side,” he said. At that, Arnold and Allen reached terms, and the plan for seizing Ticon- deroga unfolded with remarkable speed. By the evening of May 9, Allen and Arnold had their men assembled at Hand’s Cove on the eastern shore of Lake Champlain. Altogether, there were about 100 Green Mountain Boys, 40 volunteers from Massachusetts, and 20 from Connecticut. The lake crossing took place that night, but a lack of boats caused delays. By the early morning hours, 80 Green Mountain Boys were poised to strike, and Allen and Arnold, fearful that daylight would arrive before the rest of the men, chose to attack immediately.

As dawn approached on Wednesday, May, 10, 1775, it promised to be another uneventful day for the British garrison at Fort Ticonderoga. Even though armed conflict already had broken out between the Patriots and the British, no one expected anything out of the ordinary. There had not been any sign of trouble, and Ticonderoga had not witnessed a shot fired in anger in nearly two decades. Only a handful of sentries were on guard duty while the bulk of the garrison slept.

For the British troops, the quiet ended at about 3:30 AM during a few moments of unex-pected pandemonium. At the fort’s south gate, the sentry simply could not believe his eyes when a mob of unidentified men emerged from the darkness and rushed toward his post. They were drawn up in three ranks, armed, and moving fast. After issuing an abrupt challenge that went unanswered, the sentry leveled his musket at a large man who appeared to be their leader and pulled the trigger. He had taken aim in the direction of Allen, who was carrying a drawn sword and was marching in the center of the column. Fortunately for Allen, the musket lock snapped but failed to fire.

Understandably unwilling to confront the attackers by himself, the sentry ran into the fort, frantically shouting the alarm. When he reached the parade ground, he dove for cover in a bombproof shelter. Allen, who was wildly swinging his sword, led a charge to the parade ground. By this point the Americans were considerably keyed up and clearly exhilarated that they had secured the element of surprise. Allen formed the men in two ranks on the parade ground opposite the barracks. The jubilant Americans let out three huzzahs. The cheers startled the bleary-eyed Redcoats.

While the Americans were struggling to form up, another British sentry, desperately thrusting with his bayonet to keep the rebels out of the fort’s guard room, slightly wounded Gideon Warren, one of the Americans. Allen was close by and took a swing for the man’s head. At the last moment he thought better of killing the sentry. “I altered the design and fury of the blow to a slight cut on the side of the head,” wrote Allen. At that, the brief melee was over. The frightened sentry dropped his musket to the ground and bellowed for quarter. Allen relented but demanded to know where the commanding officer’s quarters were. The frightened Englishman flung his arm in the direction of the west barracks. He said that there was a staircase that led to the officers’ quarters on the second story. At that Allen was off on the run with Arnold following closely behind.

In the officers’ quarters, the fort’s high command had been caught, quite literally, with their pants down. Lieutenant Jocelyn Feltham was awakened by angry shouts of “No quarter! No quarter!” A bemused Feltham described the racket as shrieks that emanated from what was, in his words, an “armed rabble.” The lieutenant immediately leapt from bed and ran to the door of Delaplace’s room, loudly knocking on the door for orders. Delaplace, though, who was clearly a sound sleeper, was not up yet. Realizing that time was of the essence, Feltham scrambled back to his own room where he hastily donned his waistcoat and red uniform coat. He did not have time to put on his trousers.

The Americans, however, were already forcing their way into the barracks. The men in the enlisted barracks were roused from their sleep at gunpoint and made prisoners amid a good bit of shouting and cursing. Feltham darted back to the captain’s room where he found that the captain had just awoken. The two officers briefly conferred. Feltham asked for orders but just as quickly offered to force his way to the enlisted men and attempt to organize resistance. Delaplace assented to the idea as he struggled to throw on his own clothes.

The situation, however, failed to improve for the startled British. Feltham bolted out of Delaplace’s quarters and made for a stairwell but found his route of escape barred by an exceedingly noisy crowd of rebels. The lieutenant attempted to get their attention from the top of the stairwell but could not make himself heard above their shouting. He finally motioned for them to stay where they were and at last got them to quiet down. Feltham still maintained hopes that the British enlisted men would put up some sort of a fight and expected to hear the firing of muskets at any moment. Clearly stalling for time, Feltham barked a series of questions down the stairwell. The rebels were not at all pleased with his stalling tactic.

What ensued was a farcical parley for the surrender of the fort. Feltham, who still had his trousers slung across his arm, put on a bold showing for a man who wasn’t wearing any pants. He asked who the group’s leaders were, and Allen and Arnold mounted the stairs, announcing that they shared a joint command. Feltham remained defiant, demanding to know by what authority they had entered His Majesty’s fort. Arnold, playing the part of a genteel officer, calmly announced that he had received orders from Massachusetts. Allen, who was far less diplomatic, barked that his orders were from the Province of Connecticut and that he was taking immediate possession of the fort and its contents.

To get his point across, Allen menaced Feltham with a drawn sword, and his men were pointing muskets at the half-dressed lieutenant. Mistaking Feltham for Ticonderoga’s commanding officer, Allen demanded the surrender of the fort and angrily threatened that if a single British musket was fired, not a man, woman, or child in the fort would be spared. The situation was apparently cooled by Arnold, who endeavored to rein in the unruly Vermont backwoodsmen. When the Americans finally realized that they were not talking to the fort’s commander, some of the enlisted men attempted to break in the door to Delaplace’s quarters. Arnold, who was still trying to get control of the situation, held them back.

During the commotion, Delaplace, who had finally dressed, emerged from his room. Allen and Arnold conferred briefly with the fort’s commander. Understandably, Delaplace was reluctant to surrender the fort immediately. The chagrinned officer asked Allen by whose authority he demanded the surrender of Ticonderoga. Allen, perhaps confusing Delaplace for Feltham, later claimed that he blurted out one of the most legendary remarks in the annals of American history. “In the name of the great Jehovah and the Continental Congress,” Allen purportedly said.

Regardless of the precise words that passed among the three men, it was obvious that surrender was inevitable. It took little more than a half hour for the American rebels to take control of Fort Ticonderoga, and it had been a nearly bloodless coup. Feltham, who was placed under guard in the barracks, could not believe that his men failed to put up a fight. Ultimately, he correctly concluded that they had been seized in their beds. Delaplace, who was escorted down the stairs, ordered his men paraded without arms as he had surrendered the garrison. The affair was over in a matter of minutes.

An enthusiastic Allen gleefully reported the capture of the fort’s two officers, two artillerymen, two sergeants, and 44 enlisted men. More important, the fort’s entire complement of artillery had fallen into Patriot hands, and it was a considerable haul of ordnance. The Americans seized 100 cannons, one 13-inch siege mortar, and a large number of small swivel guns. To celebrate the stunning victory, Allen said the victorious American troops toasted the Continental Congress and the “liberty and freedom of America.” In plain language, the hard-drinking Green Mountain Boys broke into the fort’s liquor stores and proceeded to get inebriated.

The free flow of alcohol did little to implement an orderly occupation. In no time the troops were helping themselves to whatever took their fancy. Feltham was disgusted by the entire spectacle, later writing that the spoiling of the fort amounted to little more than “plunder which was most rigidly performed as to liquors, provisions, etc., whether belonging to His Majesty or private property.” An outraged Delaplace howled when his own private liquor stash was seized by the rebels. Allen simply brushed him off and gave Delaplace a receipt for the stolen alcohol.

For his part, Arnold was equally disgusted by what he considered a shameful lack of mil- itary discipline. Still seething that he was not in command of the operation, Arnold described the Vermonters as “committing every enormity.” He held that the Americans deliberately destroyed and plundered private property, acted boorishly, and, worst of all, completely neglected their military duties. In a matter of hours, the rebel operation had degenerated to “the greatest confusion and anarchy,” he wrote.

Despite the celebratory chaos taking place at Fort Ticonderoga, there were further prizes to be had on the northern frontier. With Fort Ticonderoga securely in their hands, the victorious Americans quickly made plans for a quick strike against the British installation at Crown Point, which seemed even more vulnerable than Ticonderoga had been. Only hours after the stunning American raid succeeded, Captain Seth Warner finally crossed Lake Champlain with Allen’s rear guard and joined forces with the main body. Allen immediately put him to work, dispatching him with 100 men to seize the skeleton British garrison at Crown Point. Warner set out on the lake. He apparently encountered stiff headwinds for he was unable to reach Crown Point until the following day. The post was guarded by a mere sergeant’s command consisting of just 12 men. Outnumbered nearly 10 to one, the Britons surrendered the post in short order. As at Ticonderoga, the capture of a handful of British infantry was far outweighed by the ordnance contained in the remains of the fort. Warner’s detachment took possession of a motley assortment of swivels, field guns, and mortars. Allen reckoned that there were more than 100 guns at Crown Point.

Notwithstanding the repeated successes, an embittered Arnold continued to seethe at the utter lack of discipline that reigned among American troops. More than that, he was clearly miffed that he lacked the authority to do anything about it. The day after the victory, he penned a report to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that gave vent to his frustrations. Fort Ticonderoga was “in a most ruinous condition and not worth repairing,” Arnold wrote. He was unable to begin the process of removing the British artillery because no one would follow his orders. And worst of all, Allen was no longer sharing any command responsibilities. In a pointed missive, Arnold gave his nemesis a backhanded compliment. Allen was “a proper man to head his own wild people, but entirely unacquainted with military service,” he wrote.

In a few days, the squabbling officers had patched up their differences enough to mount another operation. Although the British toe-hold on Lake Champlain had been eliminated, another target was close at hand. Interrogations of British prisoners revealed that a major British threat was within easy striking distance of American troops. The British sloop-of-war Royal George was moored at Fort St. Jean on the Richelieu River. With direct access to Lake Champlain, the vessel could easily command the lake and prove a decided menace to further American operations. True to form, the hot- blooded Arnold, who thus far had been denied a leadership role in the campaign, decided to launch a preemptive strike.

Arnold was able to set his plan in motion when troops loyal to him finally began to arrive at Ticonderoga. In a raid on the property of noted Tory leader Philip Skene, Arnold’s men were able to commandeer a number of bateaux and a schooner, which Arnold christened the Liberty. The amphibious strike against Fort St. Jean took shape by the middle of the month. Arnold set out with his own fleet followed closely by a scratch fleet of bateaux manned by Allen’s Green Mountain Boys. On the evening of May 17, Arnold had pulled ahead of his erstwhile companions and was closing on Fort St. Jean. After receiving an intelligence report that indicated the approach of British reinforcements, Arnold pushed his men hard to reach their objective.

The next day, Arnold achieved the martial glory he so desperately sought. His men achieved a total surprise of the thin British garrison at St. Jean, taking the fort without a fight, as well as seizing the Royal George, the most powerful ship of war on Lake Champlain. Leery of pressing his luck too far, Arnold loaded captured supplies and artillery onto the former Royal George, now named the Enterprise, and headed back for Ticonderoga. On the way, Arnold ran into Allen, who had missed the entire show. After being shunted aside at Ticonderoga, Arnold, no doubt, relished the moment. Not to be outdone, Allen pressed on to Fort St. Jean, entertaining hopes that he could hold the fort that Arnold had just abandoned. He occupied the fort, ever so briefly, and then abandoned the installation in a good bit of haste when news arrived of the approach of several companies of British regulars.

Such juvenile posturing would continue to bedevil American operations on Lake Champlain. Arnold incessantly howled for the authority to take command at Ticonderoga. Allen responded by ignoring Arnold and refused to even acknowledge his opponent in his official reports. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress, exasperated at the pointless bickering between rival commanders, finally dispatched an investigatory committee to get to the bottom of it. Outraged that the Massachusetts authorities did not automatically rally to his side, a furious Arnold resigned immediately and stalked off in disgust. In the petty game for accolades at Ticonderoga, Ethan Allen had bested all comers.

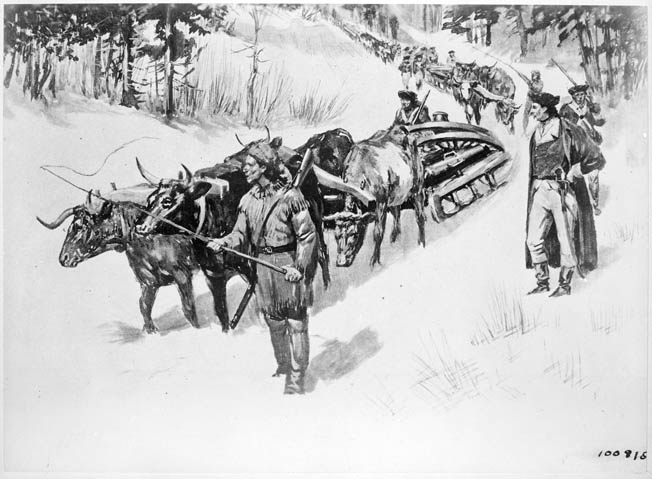

Tactically, the American seizure of Fort Ticonderoga can barely be classified as a minor skirmish. But the strategic consequences of the daring raid would remarkably affect the course of the war. Although Arnold had been frustrated in his desire to remove the artillery from Ticonderoga for siege operations at Boston, another energetic Continental officer implemented the idea. Henry Knox, a young Boston bookseller and aspiring artillery officer, advanced the scheme to General George Washington in the autumn of 1775. Knox and his men faced the herculean effort of transporting the massive load some 300 miles, in the dead of winter, through some of New England’s most rugged terrain.

Knox reached the American lines outside of Cambridge in February. To the amazement of the Continental Army, he had 58 heavy guns in tow. On the night of March 4 Washington erected impressive fieldworks on heights that commanded Boston and brought the town under the threat of artillery bombardment. With their position rendered untenable, the British evacuated the city on March 17, 1776.

The standoff at Boston was the first time that British forces faced off against the nascent Continental Army. The affair ended in an embarrassing black eye for the British due in no small part to the guns of Ticonderoga and the fierce backcountry warriors who had aggressively taken the war to the enemy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments