By Jonathan Jordan

The war map gave Adolf Hitler every reason to be confident. Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union begun on June 22, 1941, had succeeded spectacularly on nearly every front. One Soviet army after another had been smashed as Germany’s Ostheer, its army in the East, plunged deep into the industrial heart of Josef Stalin’s vast Eurasian state. By September, Hitler’s legions were within sight of Leningrad, while to the south German and Romanian divisions had swept across the north shores of the Black Sea, threatening vital petrochemical and agricultural production within the vulnerable Ukraine and Crimean regions.

Between the two sectors, Army Group Center, under Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, had taken 610,000 prisoners and destroyed 5,700 enemy tanks. Bock’s soldiers had conquered land as far eastward as the Russian city of Smolensk and were now less than 180 miles from the Soviet capital.

It was time, Hitler decreed, for a push against the center—toward Moscow.

“The Last, Great Decisive Battle of War”

Operation Typhoon, the campaign Hitler predicted would be “the last, great, decisive battle of the war,” was the result of a debate between Hitler and the army high command, Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH), over the war’s military objectives. From the beginning of Barbarossa, Hitler had insisted that the Wehrmacht give top priority to the destruction of Soviet field armies, and only afterward to the capture of strategic assets in the north and south. Prestige targets like Moscow did not figure prominently in Hitler’s planning, and as late as August 1941, his orders to OKH stressed that “the most important missions before the onset of winter are to seize the Crimea and the industrial and coal regions of the Don, deprive the Russians of the opportunity to obtain oil from the Caucasus and, in the north, to encircle Leningrad and link up with the Finns, rather than capture Moscow.”

But August brought smashing German successes to the north and south of the Eastern Front, lending credence to intelligence reports that the Soviet regime teetered on the brink of collapse. Moreover, a tempting cluster of Soviet divisions seemed to be massing west of Moscow around the cities of Vyaz’ma and Bryansk, ripe for encirclement by Hitler’s fast- moving panzer spearheads.

Hitler thus allowed himself to be persuaded by OKH and his field generals to launch a major attack against forces defending the Soviet capital. On September 6, he issued Führer Directive 35, which called for the destruction of Soviet armies opposite Army Group Center, to be followed by the pursuit of Soviet forces along the Moscow axis.

Challenges of Logistics

To put Führer Directive 35 into operation, the staffs of Army Group Center and OKH prepared plans for Operation Taifun (Typhoon), a massive offensive along a 150-mile front employing 15 panzer divisions, eight motorized divisions, and 47 infantry divisions—a total of about 1.9 million men. For the attack, Army Group Center assembled 4,000 heavy artillery pieces, 549 combat aircraft, and as many as 1,700 tanks. For once, Hitler’s generals would enjoy numerical superiority over their Soviet opponents in addition to their well-known qualitative edge.

The plan called for a double envelopment of Soviet frontline forces at the rail hub of Vyaz’ma on the Smolensk-Moscow highway. Col. Gen. Hermann Hoth’s Third Panzer Army would surround Vyaz’ma from the north, while Col. Gen. Erich Hoepner’s Fourth Panzer Army would attack from the south. Farther south, Col. Gen. Heinz Guderian’s Second Panzer Army would encircle the defenders at the crossroads center of Bryansk. Once Vyaz’ma and Bryansk were encircled and their defenders wiped out, the Soviet capital would presumably be enveloped or overrun, as circumstances dictated. Guderian would strike out for Bryansk on September 30, and the main thrust would begin on October 2.

If the Ostheer had a weakness, it was its logistical tail. Captured rail lines were handling only around half to two-thirds of their former capacity, while competing demands by garrison commanders in Poland squeezed supplies passing through to the front. To make matters worse, Typhoon’s six armies had only four major railheads from which to draw ammunition, fuel, and food, and the armies could not operate far from these railheads, given poor road networks and Germany’s chronic shortage of motor transport. Two-thirds of Germany’s artillery was still horse-drawn as Operation Typhoon began. Of the 13,000 tons of supplies per day needed to sustain Army Group Center’s 70 divisions, its motor pool was able to supply just 6,500 tons over decrepit Russian roads.

The Soviet Army’s Woeful Position

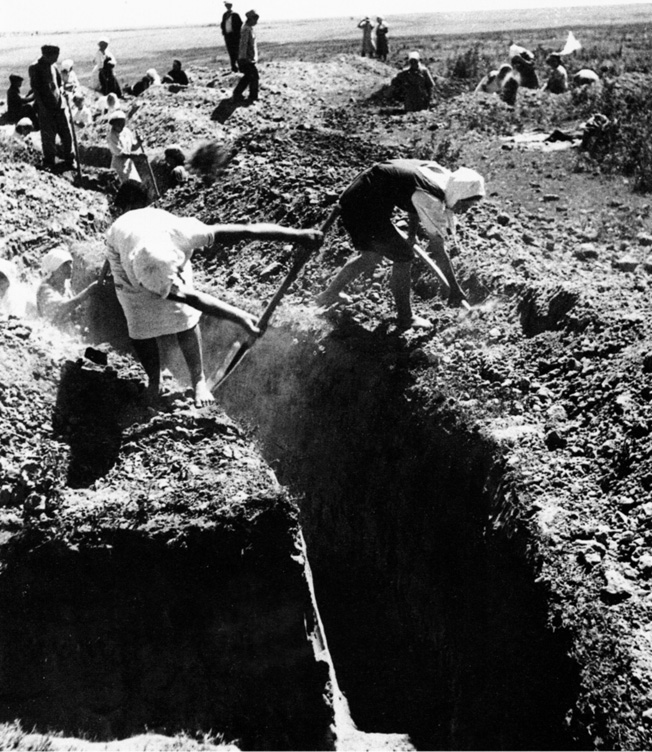

If the situation looked daunting for the German planners, it was far worse for their Soviet counterparts. The grim task of defending Moscow fell primarily to the Western Front, or army group, commanded by Lt. Gen. Ivan Koniev. Koniev’s front consisted of six rifle (infantry) armies, a five-division cavalry group, and three reserve rifle divisions, and it was supported to the south by the three-army Bryansk Front under Lt. Gen. Andrei Yeremenko. These two fronts, plus a six-army reserve front under Marshal Semyon Budenny (which had two armies plugging gaps in the front line), had been engaged in piecemeal counterattacks at Stalin’s insistence since August and were considerably worn down, so that each Soviet army was, more or less, the equivalent of a German corps.

While the Western, Bryansk, and Reserve Fronts amassed 95 divisions with 864,000 combat troops, they labored under crippling disadvantages. All three were seriously short of heavy artillery, combat aircraft, and medium tanks. The average rifle division—composed largely of ill-trained recruits—was around 5,000 to 7,000 soldiers, less than half the authorized strength of around 14,000. To make matters worse, the deeper German columns drove into Soviet territory, the less Stalin tolerated a strategy of trading space for time, which limited his generals’ options.

Putting Pressure on the Capital

The battle for the Soviet capital opened on September 30, with a lightning attack by Guderian’s panzers, which struck northeast toward the transportation hub of Orel and due north toward Bryansk. Guderian’s veterans smashed five divisions and ripped open the southern flank of the Soviet Thirteenth Army. On October 3, his panzers rolled into Orel so rapidly they overtook trams clattering down Orel’s streets, and the Thirteenth Army fled toward Bryansk.

Typhoon’s main effort began on October 2, when the Third and Fourth Panzer Armies turned on the Soviet defenders around Vyaz’ma. Third Panzer, based in Smolensk, hit the juncture of Koniev’s Nineteenth and Thirtieth Armies, rupturing the two armies’ flanks. In two days, it captured bridges over the Dniepr River, opening the northern door to Vyaz’ma.

South of Vyaz’ma, Hoepner’s Fourth Panzer Army attacked on a narrow front and broke through Budenny’s Forty-third Army, holding its LVII Panzer Corps in reserve to exploit the breakthrough. On the way, it dismantled Budenny’s Thirty-third Army, a second-echelon formation, and by October 5 Hoepner had bored a hole in Soviet lines wide enough to throw LVII Panzer Corps into the enemy rear east of Vyaz’ma.

While Bock surged forward with his armored divisions, his three infantry armies (the Second, Fourth, and Ninth) succeeded in pinning the Soviet Sixteenth, Twentieth, Twenty-fourth, and Fiftieth Armies. Fierce pressure prevented those four defending armies from either retreating or coming to the aid of their hard-pressed comrades around Vyaz’ma and Bryansk.

One Million Men

At the time Typhoon was launched, the Kremlin was still preoccupied with its Ukrainian front; it took three irreplaceable days before Stavka, the Red Army high command, awoke to the threat posed by Army Group Center and summoned reserves from the Urals, Central Asia, and the Far East. To the north, General Koniev threw whatever reserves he could find into a futile counteroffensive to halt the Third Panzer Army, but these unlucky units were driven back with heavy losses. In the center, Marshal Budenny’s Reserve Front, which comprised largely militia or reconstructed units, collapsed entirely before the weight of the Fourth Panzer Army’s assault, and by October 4 Budenny’s front was virtually destroyed. Stalin, furious with the performance of his generals, sacked Koniev (and considered executing him), replacing him on October 5 with his top commander from Leningrad, General Georgi Zhukov.

By October 6, the Soviet picture had grown worse. Koniev’s orders to his Sixteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Armies to retreat toward Vyaz’ma could not be heeded due to the intense pressure from Bock’s Fourth and Ninth Armies. Budenny’s Thirty-second Army, which guarded the approaches to Vyaz’ma, collapsed under withering armored attacks from north and south of the city, and on the morning of October 7, panzers linked up east of Vyaz’ma, forming a pocket that trapped some 400,000 soldiers from the Sixteenth, Nineteenth, Twentieth, Twenty-fourth, and Thirty-second Armies. That evening, five German infantry corps, plus heavy artillery and Luftwaffe bombers, were called in to begin the kessel (cauldron) battle that would result in the destruction of 25 rifle divisions and five tank brigades over the next five days.

Farther south, General Guderian closed the Bryansk pocket, although his mobile forces were delayed when his fuel supply gave out on October 3. Three days later, his panzers finally reached Bryansk, and by October 9 he had loosely encircled the Soviet Third, Thirteenth, and Fiftieth Armies. But Guderian failed to seal the pocket effectively, and from October 9 to 13 large portions of the Third and Thirteenth Armies limped away, while parts of at least seven rifle divisions managed to escape the cauldron.

All told, the first phase of Typhoon was another disaster for the Red Army. Despite the imperfect closure of the Bryansk pocket, Bock estimated that his army group had captured 673,098 prisoners, killed around 300,000 defenders, and destroyed or captured 1,277 tanks and 4,378 artillery pieces. The Red Army had lost 64 rifle divisions, 11 tank brigades, and 50 artillery regiments—about one million men—during Typhoon’s first two weeks, and Hitler’s propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels, confidently informed foreign correspondents, “The annihilation of Timoshenko’s [sic] army group has definitely brought the war to a close.”

T-34s Stall for Time

East of Bryansk, Guderian’s spearhead, the XXIV Panzer Corps, sat idle at Orel for two days of excellent weather while supply convoys went back to Novgorod-Seversky to bring up more fuel. When Guderian resumed his drive toward Tula, an ordnance center along the Orel-Moscow highway, a fierce counterattack by Soviet T-34 medium tanks slowed his progress at the Lisiza River. By October 7, the first light snows began to fall, and despite artillery and Stuka dive-bomber support Guderian’s spearhead ground to a halt before Soviet delaying actions at the roadside town of Mtensk. Soon the Russian razputitza, or “period of mud,” set in, immobilizing Guderian’s mechanized forces until winter freezes hardened the roads.

Reflecting complete confidence in its ability to take Moscow at will, OKH convinced Hitler that Stalin’s Northwestern and Southwestern Fronts could also be destroyed while an all-out lunge at Moscow was attempted. Ninth Army and Third Panzer Army, therefore, were ordered to send detachments north to Rzhev and Kalinin (respectively 200 and 120 miles northwest of Moscow), which they captured by October 14. Guderian was similarly directed to dispatch his XLVIII Panzer Corps south toward Kursk. The result was a dilution of Army Group Center’s armored strength at the time Zhukov was placing every available platoon on the likely approaches to the Soviet capital.

While the Vyaz’ma pocket was being liquidated, a halfhearted German pursuit under Hoepner’s Fourth Panzer Army commenced, using the SS Das Reich Motorized Infantry Division as its spearhead. Before long, however, Das Reich was stopped cold on the Minsk-Moscow highway by two newly formed tank brigades equipped with the excellent T-34 medium tanks. The two tank brigades fought tenaciously for four days, delaying Fourth Panzer Army’s push toward Moscow and giving Zhukov some badly needed time to move forces—including strategic reinforcements from Siberia—into position at Borodino, Yelnya, and Mozhaisk, a trio of strongpoints west of Moscow.

Guderian’s delays in pushing beyond Orel, unexpectedly fierce Soviet resistance around Borodino, and the diversion of part of Army Group Center toward Kalinin gave Zhukov time to throw together parts of 18 rifle divisions and 11 tank brigades—around 90,000 men—to hold back the gray tide. He set up a new defensive line about 75 miles west of Moscow, centered around three cities on the main approaches to the capital—Volokolamsk, Mozhaisk, and Maloyarsoslavets. But by October 15, Bock was ready to attack once again.

Maloyarsoslavets, guarded by the Forty-third Army, was the next of Zhukov’s positions hammered by the powerful LVII Panzer Corps. The city fell on October 18, but Soviet defenders were reinforced by the Thirty-third Army and managed to prevent Hoepner’s panzers from exploiting the breach. To the north, meanwhile, savage fighting at Volokolamsk further delayed the German advance until October 27, when snow, rain, and mud began to affect Bock’s mobility in a serious way.

The Miserable Russian Weather

At Mozhaisk, Zhukov faced his most serious crisis. There, the SS Das Reich and 10th Panzer Divisions met stiff resistance at the nearby town of Borodino, which was guarded by the 32nd Rifle Division, some 50 tanks, and a like number of artillery pieces. It took two days for Hoepner’s panzers to grind through the defenses there, but by October 18 Das Reich had blasted its way into Mozhaisk, 55 miles from Moscow. With the fracture of the Mozhaisk Line, Germany now occupied roughly 600,000 square miles of former Soviet territory. Zhukov was running out of room.

The significance of the German victory at Borodino was not lost on Muscovites. In 1812, Napoleon’s success there had opened the doorway to French occupation of Moscow. Residents began fleeing the capital, and the government evacuated most offices to the east, although Stalin and the Army’s high command remained within the city.

As the fate of Moscow hung in the balance, Bock’s logistical vulnerabilities began catching up with him. Miserable weather and muddy roads had hampered his ability to move supplies—especially fuel and ammunition—to frontline troops. That, plus a lack of supply trains reaching his railheads, meant that from October 24 into November Army Group Center was forced to halt and settle for a war of attrition that it could ill afford. The only German gains over the next few weeks would be along Guderian’s sector to the south.

Guderian’s objective after seizing Orel was to capture Tula, 100 miles south of Moscow. Having been stymied at Mtensk until October 11, then spending 11 days bringing up additional fuel and ammunition, on October 22 Guderian sent his XXIV Panzer Corps with three infantry divisions and flanked the Soviet defenders the following day. Six days later, Guderian’s spearheads were able to pierce defenses south of Tula and attempt a direct assault on the city.

In a heroic last-stand effort, local militia, NKVD security troops, and antiaircraft crews fought off Guderian’s lead units just long enough for the 32nd Tank Brigade and two rifle divisions to come to their rescue. Deep mud limited Guderian’s mobility until the surrounding roads froze; Tula, like Moscow, gained a respite for the moment.

Zhukov’s Fresh Reserves

Guderian prepared to renew his assault on Tula by bringing up the rest of his army in a flanking movement to the east, but by early November Second Panzer Army had bypassed so many smaller Soviet units that Guderian’s right flank was seriously exposed. He posted his LIII Corps on the right to deal with threats to his line of communications, but spoiling attacks by the Soviet Third and Fiftieth Armies set off a 10-day running battle that further delayed Guderian’s drive on Tula until November 18 and forced Second Panzer Army to consume vital ammunition and fuel stocks.

By the end of October, the vast human resources of the Soviet empire had begun collecting on the Moscow axis. That month, Zhukov received 10 rifle divisions, 19 armored units, a cavalry division, five divisions of militia, and one airborne corps. During November, he would receive another 22 rifle divisions, 17 rifle brigades, 14 cavalry divisions, four armored units, and 11 ski battalions. By November 15, Zhukov and Koniev (whom at Zhukov’s request had been given command of the armies fighting at Kalinin) had assembled 38 infantry divisions, three tank divisions, and a dozen cavalry divisions, plus another 14 tank brigades. While many of Zhukov’s units would be thrown into combat with little or no training, he now had sufficient numbers to make a decent stand around his capital.

West of Moscow, Zhukov deployed seven armies—from north to south, the Thirtieth, in the north near the Moscow Sea and Volga Reservoir; the Sixteenth, along the Lama River; the Fifth, behind Mozhaisk at the town of Tuchkovo; the Thirty-third, along the Nara River south of the Minsk-Moscow highway; and the Forty-third, farther up the Nara. Below that, the Forty-ninth Army was charged with holding back Guderian’s panzers from the road below Tula, while the Fiftieth Army held Tula proper.

Zhukov, whom Stalin had warned would face a firing squad if German jackboots touched Moscow’s streets, did not wish to repeat the mistakes made by Stavka when it had dispersed its strength in piecemeal counterattacks. A ruthless man who occasionally had incompetent generals shot as examples to others, Zhukov was not afraid to give Stalin his unvarnished military opinion. However, Stalin once again insisted upon offensive action, and Zhukov had no choice but to appease the dictator by conducting a number of spoiling attacks that dispersed his reserves but did little to create decisive results.

“One Final Heave, and We Shall Triumph”

In Berlin, Hitler faced the same crossroads decision that Napoleon faced at Smolensk 129 years before: should he press on toward Moscow, or should his men go into winter quarters and rebuild their strength? OKH intelligence reports claimed that the remaining defenders were demoralized remnants of defeated field armies, plus a scratch collection of untrained militia and NKVD troops. Hitler predicted to the Wehrmacht’s operations chief, General Alfred Jodl, “One final heave, and we shall triumph.” Thus, on November 12, OKH ordered Bock and his army commanders to resume their offensive on November 15.

The second phase of Operation Typhoon called for Bock to encircle Moscow with another double envelopment. The Third and Fourth Panzer Armies (a total of 18 divisions) would attack from the north, while Guderian’s Second Panzer (nine divisions) would capture Tula and drive toward Moscow from the south. To keep Zhukov from reacting to these flanking movements, Field Marshal Guenther von Kluge’s Fourth Army would launch pinning attacks with his 14 infantry divisions along the Nara River.

The plan seemed sound, but its execution, Bock knew, would be difficult. He had the equivalent of about 38 divisions for this last phase of Typhoon—roughly half the number that participated in his initial onslaught. To the north, the Third Panzer Army had committed its reserves around Kalinin, while local Soviet counterattacks forced Bock to deploy the Second and Ninth Armies on his exposed flanks.

Bock’s logistical constraints also had not eased. He had no significant stockpiles at jumping-off points for his men, and the OKH quartermaster department, unable to supply Army Group Center’s requirements of 30 trains per day, simply cut the army group’s quota by one-fourth; even that reduced amount did not get through to Bock’s forward railheads. It would be a close battle for both armies.

Deciding the Fate of Moscow

The final struggle for Moscow opened with a three-division attack by Ninth Army’s XXVII Corps, supported by the 1st Panzer Division, against Maj. Gen. Dmitri Lelyushenko’s Thirtieth Army at the Moscow Sea. The Thirtieth, still recovering from bitter fighting around Kalinin, fell back toward Klin, 52 miles from the capital. This retreat allowed Third Panzer Army to move over the Lama River, 60 miles from Moscow.

On November 18, the main German thrust began as Fourth Panzer Army’s V Corps and XLVI Panzer Corps, six divisions in all, ripped open a hole between the Thirtieth and Sixteenth Armies. The Sixteenth, commanded by Maj. Gen. Konstantin Rokossovsky, was forced to withdraw east toward Istra, 36 miles west of Moscow, leaving a gap between the two armies that Hoepner obligingly exploited with two corps.

By November 23, Klin was in German hands, and Thirtieth Army was in peril. But with Koniev launching division-sized counterattacks from the Kalinin region, Bock could not afford to leave his left flank open. He ordered Col. Gen. Adolf Strauss’s Ninth Army to assume the defensive and keep Koniev’s forces away from his panzers moving against Moscow.

While Thirtieth Army was falling back toward the Volga Reservoir, 35 miles north of the Kremlin, Rokossovky’s Sixteenth Army, west of Moscow, was taking a beating around Istra. There, his 78th Rifle Division, newly arrived from Siberia, was putting up a desperate defense against the SS Das Reich Division. The 78th conceded the town on November 27, but not before inflicting 926 casualties on Das Reich and taking a good deal of the fight out of that elite unit. In addition to inflicting German casualties, the battle for Istra bought Zhukov critical time to establish yet another defensive line 21 miles northwest of Moscow.

Time was, for the moment, on Zhukov’s side. The delaying actions around Klin and Istra allowed him to withdraw troops east and avoid another pocket disaster, while harsh weather and supply shortages seriously hampered Bock’s ability to move forward. But Bock had one last attack left in his army group, and no one knew whether it would end inside or outside the Kremlin walls.

On November 27, advance units of the LVI Panzer Corps managed to reach the Moscow-Volga Canal, but they were thrown back by lead elements of the First Shock Army, and forward momentum on the north side of the capital was lost. Northwest of Moscow, on November 30 the 2nd Panzer Division captured the town of Krasnaya Polyana, 17 miles away, but fierce resistance by Rokossovsky’s army, increasingly severe weather, and fuel shortages stopped Hoepner’s advance there.

Kluge’a Late Attack

To the south, around Tula, Guderian spent late November fending off counterattacks against his line of communication and gathering fuel to launch one last attack. Meanwhile, at Tula, the Red Army moved replacements into Lt. Gen. Ivan Boldin’s Fiftieth Army. Spoiling attacks by Boldin’s Siberian 413th Rifle Division damaged Guderian’s right flank badly enough to require him to throw off divisions to protect his flank, delaying his planned encirclement of the city.

It was not until November 24 that Guderian was able to send his XXIV Panzer Corps northeast of Tula in an effort to encircle the city. But his all-out effort ground down against unexpectedly strong Soviet defenses, and Guderian, to his disgust, received no help from the plodding Kluge, whose Fourth Army provided negligible support from its divisions north of Guderian’s advance. Although German tanks briefly cut the Tula-Moscow highway on December 3, the next day armor dispatched by Zhukov forced Guderian to withdraw from the city’s outskirts and stand on the defensive.

South of the Minsk-Moscow highway, Kluge’s army sat idle through the late November maelstrom, keeping watch along the Nara River and giving Zhukov the opportunity to move units from his Fifth and Thirty-third Armies north to assist the hard-pressed Rokossovsky. It was not until the early hours of December 1 that Kluge launched a four-division attack against well-prepared Soviet defenses. Kluge’s troops performed superbly, but by then Hoepner’s Fourth Panzer Army had been stopped, and there was little that the Fourth Army could do at this late date. After Zhukov moved his reserves back to the center to support the crumbing Thirty-third Army, Kluge retired across the Nara, effectively quitting the battle. As Zhukov later commented, “In the absence of attacks at the center we were able to shift all our reserves, down to divisional reserves, from the center of the front to parry the enemy’s strike forces on the flanks.”

Rolling the Germans Back

Hitler’s Wehrmacht had reached its high- water mark. From the Moscow suburb of Khimki, less than 12 miles from the Kremlin, reconnaissance troops allegedly could see the gleaming onion domes of the city in the distance. But they were dangerously low on fuel and ammunition. They had sustained around 155,000 casualties and lost over 700 tanks in the second phase of Typhoon, and although OKH did not know it, the Red Army now held a numerical advantage. On December 8, Hitler agreed to suspend offensive operations, citing uncooperative weather, but ordered Bock to hold all conquered territory.

Unbeknownst to OKH, three fresh armies— the First Shock, Tenth, and Twentieth—had arrived at Moscow, and on November 30 Stalin approved a counteroffensive proposal employing six armies. The new armies lacked significant armor, but Zhukov planned to use them to pull the steel fangs out of Bock’s panzer divisions.

Soviet counterattacks began on December 5 at the north end of the line, east of Klin, where the Third Panzer Army deployed three panzer and two motorized infantry divisions. Col. Gen. Hans Reinhardt, who had replaced Hoth as commander of Third Panzer after Typhoon’s launch, made the mistake of keeping his few operational tanks, only around 80 or so by now, close to his front lines. They were therefore unable to act as a mobile reserve to plug cracks in his front and were vulnerable to a rapid thrust.

On the morning of December 6, Thirtieth Army flung three rifle divisions and two tank brigades at Reinhardt’s overstretched 14th and 36th Motorized Infantry Divisions. The First Shock Army joined in the attack, and Twentieth and Sixteenth Armies began pressing attacks along the juncture of the Third and Fourth Panzer Armies. Reinhardt ordered Third Panzer to fall back upon Klin, while Hoepner withdrew Fourth Panzer Army to Istra.

As Hoepner and Reinhardt were pulling back, the Soviet Fifth Army joined the battle, and Third Panzer suffered heavy losses in artillery and vehicles as Reinhardt tried to cobble together a Kampfgruppe (battle group) from two panzer divisions to hold back the red tide. Miserable weather and fuel shortages impeded cooperation between the two panzer armies, and by December 11 Rokossovsky had pushed the Germans out of Istra. Bock’s left wing was in danger of collapse.

On December 12, Rokossovsky moved in for the kill, sending two tank brigades, two motorized regiments, and two cavalry units around Third Panzer Army to cut off its line of retreat. His force captured the road from Klin on December 14, isolating four panzer divisions plus the hard-pressed 14th Motorized Infantry Division. Leaving behind much of their heavy equipment, the divisions trapped at Klin forced open the road to Kalinin just long enough to escape the rapidly closing noose, and by December 15 Third and Fourth Panzer Armies again were in retreat.

To the south, around Tula, Boldin’s Fiftieth Army, plus reinforcements from the I Guards Cavalry Corps and the newly formed Tenth Army, battered Guderian’s front and flanks. At the same time, Stavka sent two reinforcing armies toward Tula, and by early December those armies had converged upon Second Panzer’s flanks. As in the north, three of Guderian’s infantry divisions were threatened with encirclement, but all managed to withdraw southwest with heavy losses. Soviet thrusts at the juncture between Fourth Army and Second Panzer Army threatened to isolate Guderian, and by December 12 he was in retreat toward Orel. Moscow had been saved.

Aftermath of Operation Typhoon

Operation Typhoon was a near run thing for the Soviet Union. From September 30 to December 15, the Red Army sustained roughly 1.5 million casualties (some 350,000 in December alone), and the Soviet government had been forced to evacuate its capital. Army Group Center, for its part, lost over 150,000 men.

Particularly crippling for the Ostheer was the loss of heavy equipment—as many as 800 tanks, 983 artillery pieces, 473 heavy mortars, and 800 antitank guns were destroyed or abandoned during December alone.

Perhaps the greatest damage to the Nazi war machine was psychological. The “subhuman” Slavic troops had shattered the myth of Wehrmacht invincibility. Hitler’s confidence in his generals was irredeemably shaken, and in short order he relieved the head of OKH and took personal command of the Army. He sacked Bock, three of the six army commanders involved in Typhoon (Guderian, Hoepner, and Strauss), and four of the 22 corps commanders.

The first phase of Operation Typhoon, culminating in the liquidation of the Vyaz’ma and Bryansk pockets, was brilliantly conceived and almost flawlessly executed. Its few shortcomings can be attributed to logistical shortages and to Guderian’s failure to close the Bryansk pocket aggressively, allowing a number of Soviet troops to escape to Tula, where they would join the reconstituted Fiftieth Army in defense of that city.

The operational pause during early November, when the Red Army was reeling, was due to structural flaws in the Ostheer that prevented adequate fuel and ammunition from reaching Army Group Center’s front lines. By the time Bock was ready to resume his attack, both numbers and climate had begun to favor Zhukov.

It was the second phase of Operation Typhoon, the last push to Moscow, that was the most flawed of all. Harkening back to the German experience at the Marne in World War I, when Germany might have defeated France had it thrown in its last reserves, both OKH and Bock were prepared to commit every remaining soldier on the assumption that the Red Army simply had no reserves left. Hitler allowed himself to be persuaded by overly optimistic reports claiming that the Red Army and Stalin’s dictatorship had sustained so many casualties that they could be toppled with one last shove. When trained reinforcements arrived from Siberia and the Far East, and when Stavka proved capable of forming fresh armies, the critical assumption underlying Hitler’s lunge against the Soviet capital evaporated. The Soviet Union would not suffer the fate of Poland, France, and the Low Countries.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments