By Mark Simmons

“U-64 was seen on the surface at the top of Herjansfjord near Bjrekvik. I selected the two anti-submarine bombs and put the Swordfish in a dive and released the bombs at 200 feet. I couldn’t see the bombs fall as we pulled out but Pacey [Leading Airman Maurice Pacey] saw the starboard bomb fall close alongside and the port one hit just abaft the conning tower; the U-boat was already sinking when I could see her again.”

So recorded Petty Officer Pilot F.C. Rice flying a float Fairey Swordfish from the battleship Warspite. U-64, a brand-new type IXB U-boat, was the first German submarine to be sunk by an aircraft in World War II, and it took place in Norwegian waters.

On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany after the invasion of Poland two days earlier, Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty, returning to the old post he had left dejected after the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign of World War I; he joined the War Cabinet the next day.

Churchill had several pressing concerns before him, including the inadequate defenses of the Royal Navy’s anchorage at Scapa Flow and the shortage of destroyers, but top of the list was Norway and how to stop the Germans from using its territorial waters to gain access to the Atlantic and the convoy routes.

Of equal importance was stopping the transportation of Swedish iron ore to Germany from the port of Narvik, which would begin as soon as ice formed in the Gulf of Bothnia.

On September 19, he brought to the attention of the War Cabinet the need to mine Norwegian territorial waters to stop this trade. In winter the main weight of the trade between Sweden and Germany was via Narvik and then down through territorial waters. These sheltered waters are known as the Leads. Using this route, ships could make the whole voyage to Germany without leaving territorial waters until inside the Skagerrak.

Interrupting this supply route, which was used from October to the end of April, would severely restrict German industry. Ten days later, in a paper to the cabinet, Churchill again raised the issue, recommending “drastic action.”

Days later Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, German Military Intelligence, learned of “British intentions to violate the territorial integrity of Norway.” Canaris wasted no time in personally taking the information to Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, commander in chief of the Kriegsmarine.

Raeder was startled by the visit—not only by the news, but that Canaris had brought it himself as the men held each other in contempt. He wrote in his memoirs, “The report of the Abwehr chief assigned greater significance by virtue of the fact that he deemed it necessary to present it in person, something he would do only on exceptional occasions.”

In October 1939, Raeder twice raised the subject with Hitler; he argued the best way to secure the trade was to obtain bases in Norway, which would also enhance the Navy’s ability to attack Britain’s convoy routes. However, the Führer took little interest, being totally absorbed at the time in plans to invade the Low Countries and France.

In December, the situation was changed dramatically by the Russian attack on Finland. It raised the possibility of British and French troops being sent to Finland through Norway—even an Allied occupation of the country became a German fear. Raeder went as far as to suggest the loss of Norway might decide the outcome of the war.

At the same time, Churchill was still pressing the War Cabinet. His memorandum began, “The effectual stoppage of the Norwegian ore supplies to Germany ranks as a major offensive operation of the war. No other measure is open to us for many months to come which gives so good a chance of abridging the waste and destruction of the conflict, or of perhaps preventing the vast slaughter which will attend the grapple of the main armies.”

The cabinet, however, would not approve the action, preferring diplomatic protests to Norway about the misuse of her territorial waters by Germany. However, the chiefs of staff were ordered to plan for action and intervention in Norway.

Raeder by now had brought an idea to Hitler that caught his attention. Alfred Rosenberg, head of the Nazi Foreign Policy Bureau, had put Raeder in touch with Vidkun Quisling and Albert Hagelin, the leaders of the small Norwegian Nazi party. They were eager to take over the country with German support.

Hitler met with Quisling three times in December, stating that he favored a coup d’état, but if this failed he was prepared to occupy the country by force. In January 1940, with the postponement of the offensive in the West until the spring, Hitler turned his attention to Norway. On January 27, the German High Command (OKW) started working on the details for the occupation of Denmark and Norway.

In early January, Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary, told the Norwegian ambassador that Britain would act to prevent the misuse of neutral waters by German ships.

Yet the Norwegians remained unmoved in their neutrality. A week later the War Cabinet decided to begin to prepare for a high-level mission to Oslo and Stockholm to explain the Allied position. Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, with his chiefs of staff and Churchill, went to Paris to confer with the French, who largely agreed with the stance Britain had taken.

Shortly after the meeting, the British 42nd and 44th Divisions began to make preparations for operations in Norway. With the Baltic Sea routes due to open shortly, it would mean the latest the expeditionary force would need to start loading was early March.

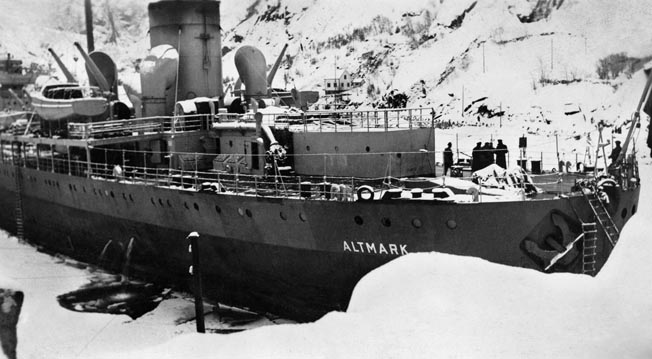

However, the Altmark incident concentrated the collective minds of both sides. The ship, a 12,000-ton tanker, had been the pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee’s supply ship. The Graf Spee had been raiding British commerce in the South Atlantic, and Altmark served as a prison ship, picking up survivors from British merchant ships sunk by Graf Spee.

After the Graf Spee was damaged in a running fight with British warships, her captain, Hans Langsdorff, scuttled her off the River Plate estuary at Montevideo, Uruguay, on December 13, 1939. The Altmark then sailed back across the Atlantic and headed for Norway with 299 British prisoners locked below decks.

The Altmark, having avoided capture, arrived in Norwegian waters nine weeks later. The ship pretended to be Norwegian as she sailed south through territorial waters, but the British alerted the Norwegians to her presence in their waters. Norwegian patrol boats discovered her true identity, boarded her, and made a cursory search, but turned a blind eye for fear of provoking the Germans.

On February 15, a British aircraft spotted the ship off Egersund. The Fourth Destroyer Flotilla under Captain Philip Vian was in the area looking for iron ore carriers. The light cruiser Arethusa sighted the Altmark on the afternoon of the 16th, but two Norwegian patrol boats prevented Vian’s destroyers from getting a boarding party on board.

That night the Altmark took shelter in Jossingfjord, a sheltered inlet between coastal cliffs south of Stavanger. Without consulting Admiral Charles Forbes, C-in-C of the Home Fleet, Vian, urged on directly by Churchill, violated Norwegian neutrality, blocking the exit of the fjord.

A boarding party from the destroyer HMS Cossack climbed aboard the Altmark, and a short, fierce fight took place in which seven German sailors were killed and 11 wounded. One of the released prisoners stated that the first they knew of the operation was when they heard a shout, “Any Englishmen here?” from the boarding party.

When they replied, “Yes, we are British,” the reply was, “The Navy’s here,” which brought cheers. The Altmark was stripped of all weapons but left intact.

The Altmark incident infuriated Hitler; he resolved to invade Norway and demanded an immediate appointment of a commander for the operation codenamed Weserübung. The head of OKW, General Wilhelm Keitel, recommended General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, who arrived in Berlin on February 20.

Hitler saw him only for a few minutes; most of the time he spent “marching up and down” explaining why “the occupation of Norway by the British would be a strategic turning movement which would lead them into the Baltic, where we have neither troops or coastal fortifications.” It would put all they had won and were about to win at risk. Invading Norway would ensure Germany’s iron ore supplies and give the fleet freedom of movement. Finally, he appointed Falkenhorst to command the expedition.

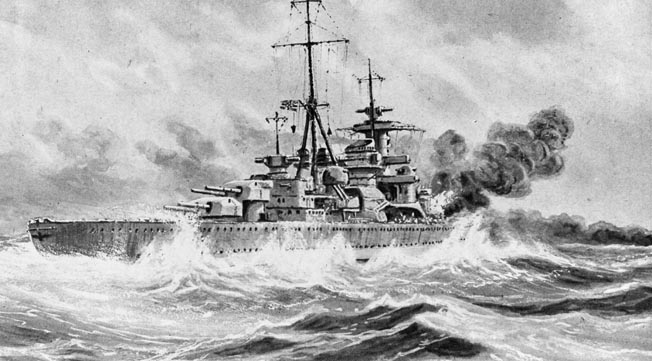

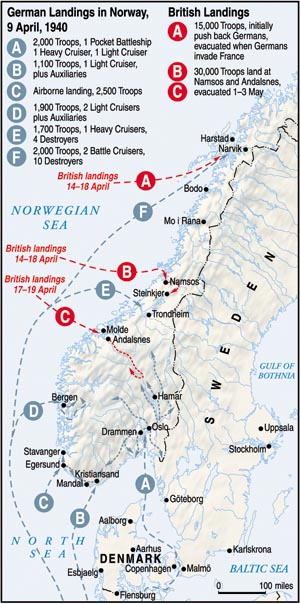

Operation Weserübung, scheduled to start on April 9, would consist of five main groups to invade Norway by sea and air. Ten destroyers of Group One would take three battalions of the 3rd Mountain Division to Narvik. Group Two—the heavy cruiser Hipper and four destroyers—would land the two remaining battalions at Trondheim. These groups would be the first to sail to the north of the country, covered by Vice Admiral Günther Lütjens with the battlecruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst, flying his flag in the former.

Group Three, with the light cruisers Köln and Königsberg supported by torpedo boats and other light craft, would land two battalions of the 69th Infantry Division at Bergen, while two more would be flown into Stavanger and another on D+1. The rest of the division would arrive overland from Oslo.

Group Four, with the cruiser Karlsruhe and a mixed force of light craft, would land a battalion at Kristiansand. Group Five—the cruisers Blücher and Emden and the pocket battleship Lützow—would deliver two battalions of the 163rd Infantry Division to Oslo, while the rest of the division would be flown in.

Supporting the Army and Navy would be the Luftwaffe’s X Air Corps with about 1,000 aircraft. Made up of about 300 medium bombers (Heinkel He-111 and Junkers Ju-88 and Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers), three fighter wings with 90 Messerschmittt Me-110 aircraft, many of these were expected to be operating from Norway by D+2. Two medium bomber wings would be held in Germany for operations against the British Fleet. Five hundred transport Junkers Ju-52 aircraft were available to deliver troops and supplies.

In a largely separate operation, two infantry divisions and a motor rifle brigade would overrun Denmark on April 10.

Relations between the three German service branches during this planning stage were far from harmonious. OKW and the staff of XXI Corps were against the naval plan to take ships back to Germany as soon as the landings were complete. Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, came to support the Army view, feeling his aircraft would be able to protect the ships.

Hitler agreed with the Navy on Narvik but felt there was no need for a rapid return of ships farther south. Within the naval command there were doubts that the battle cruisers should be used so far north; yet, without their presence the Narvik and Trondheim groups would be at the mercy of the enemy.

Also, using the warships in this way might induce the enemy to think they were trying to break out into the North Atlantic, forcing the enemy to cover the Shetlands–Iceland line. With the Lützow, which was scheduled to deploy on an Atlantic sortie, Hitler insisted she should carry a battalion of mountain troops to Trondheim and then make her break from there. However, engine problems would rule out the Atlantic cruise, and she would return to the Baltic to join the Oslo invasion group.

On April 3, the British cabinet finally authorized the Admiralty to mine the Norwegian Leads on April 8—an operation called Wilfred. They expected a German response. Churchill wrote that it was “also agreed that a British brigade and a French contingent should be sent to Narvik to clear the port and advance to the Swedish frontier. Other forces should be dispatched to Stavanger, Bergen, and Trondheim, in order to deny these bases to the enemy.”

The War Cabinet and Churchill believed the Germans could not reach the west coast of Norway in the face of British naval supremacy. Yet they had had plenty of warning about German preparations from SIS (Special Intelligence Service, later MI6) and diplomatic sources. There were reports of amphibious exercises in the western Baltic, and the assembly of troops and ships fitted to carry tanks. They were even warned from an Abwehr source that the attack would take place on April 9, but they failed to study these reports in detail, so the warnings went largely unheeded.

However, the first move was made by Britain when Wilfred got underway on April 5 and three groups of ships set off to mine the waters off southwest Norway.

One was to act as a lure off Kristiansand, one was withdrawn on the 8th, and the third force of four destroyers was tasked with laying a minefield in the approaches to Narvik. Vice Admiral W.J. Whitworth left Scapa Flow with the battlecruiser Renown and four destroyers to act as support for the Narvik group. They met off the Shetlands on the morning of April 6, planning to be off Vestfjord in the Lofoten Islands the next night, ready to begin minelaying the next morning at dawn.

One of the ships, the destroyer Glowworm, lost contact with the group led by the battlecruiser HMS Renown. Two days later the destroyer signaled Whitworth that she was returning, as she was unsure of her position, being unable to obtain a fix in the heavy weather. Her next signal was that she was in action with enemy destroyers.

She had been some 200 miles northwest of Trondheim, and around 9 am she reported another sighting—the new contact was the heavy cruiser Hipper. After being hit by several rounds from the German ship, the Glowworm rammed the cruiser at full speed, tearing a 120-foot gash in her side before the 1,350-ton destroyer was sunk with the loss of all hands.

By then almost the entire German fleet was at sea in their various groups; Operation Weserübung had begun. Whitworth, who was in a covering position off Vestfjord with Renown and one destroyer, turned southward and ordered his ships up to the best speed they could manage against a heavy head sea.

The British were ready to implement “Plan R4” to occupy four Norwegian west coast ports—Narvik, Trondheim, Bergen, and Stavanger—in the event of a German reaction to Wilfred. Assembled in the Clyde were transports and escorts for the first two ports while in the Firth of Forth was a force of four heavy cruisers with the Scots Guards embarked and six destroyers to take the two southerly ports.

The Home Fleet had put to sea at 8 pmon the 7th, with Admiral Forbes commanding the battleships Rodney and Valiant, the battlecruiser Repulse, two cruisers, and 10 destroyers. He sent Repulse with a cruiser and four destroyers ahead at full speed to the north to reinforce Whitworth while he headed for a position farther south closer to Trondheim, which he reached at 3:30 pm on the 8th.

The same day the Polish submarine Orzel sank a German troop transport heading for Bergen. Survivors were picked up by Norwegian ships, whose sailors told them they were on their way to “protect” Norway against an Anglo-French attack.

The 10 destroyers of Group One, led by Commodore Friedrich Bonte in the Wilhelm Heidkamp, reached the mouth of Vestfjord at 8 pm on the 8th. The soldiers of the 139th Mountain Regiment, crammed below decks, suffered from seasickness as the ships moved north, tossed about by mountainous seas.

Reaching sheltered waters came as a great relief. Bonte left one ship there as a picket and detached two more to capture the batteries at the entrance of Ofotfjord. Three more went on to capture the barracks at Elvegardsmoen in the Herjangsfjord 10 miles north of Narvik.

The rest of Bonte’s force arrived at Narvik at 4:15 amon the 9th. There, two old coast defense ships fired warning shots at the Germans, refused to surrender, and both were sunk by gunfire and torpedoes. Ashore there was no further resistance as the Norwegian garrison commander surrendered. General Edouard Dietl of the Mountain Regiment established his headquarters in the Grand Hotel at 8:10 on the morning of April 9, reporting to high command that Narvik was in German hands.

Meanwhile, Whitworth received a warning from the Admiralty that Narvik might be under threat, so he altered course to cover the approaches to Vestfjord. Then, with visibility reducing, he turned back to the north to rendezvous with his destroyers. He was in a quandary over his options for he had no idea of enemy intentions.

However, in the bad weather that had reached storm force, he could not keep his large formation close to Vestfjord. At 10 pm he told Repulse that he was 40 miles southwest of the Skomvaer light and he intended to patrol the entrance to Vestfjord once the weather improved.

In the early hours of April 9, shortly after Whitworth’s ships turned back toward land, they encountered the German battlecruisers which had released their destroyers near the unguarded approaches to Vestfjord and then were moving out to sea in a sweep.

It was around 3:30 am in the twilight of an arctic dawn that Whitworth, aboard Renown, spotted Scharnhorst. Then a second large ship came into view, mistakenly thought to be the Hipper but actually the Gneisenau.

It was the destroyer HMS Hardy that first opened fire, and then Renown opened fire at extreme range. Petty Officer Neal in the Hardy watched the battle: “At 4:10 we engaged Scharnhorst. We played our part alongside Renown. We blazed away at both enemy ships in a sea that tossed us about savagely.”

But the weather proved too much for the destroyers of the Second Destroyer Flotilla. Neal continued, “Renown kept firing away. It was possible to see her shells hitting Gneisenau. Every hit brought a cheer.”

Tom Bailey, a telegraph operator aboard Renown, was in his first action. He said, “We were hit several times, one 11-inch entering the half-deck, but fortunately not exploding. Either due to a near-miss or an extra-big wave, I was thrown against the bulkhead, and the welded screws that held the channel plate for all the electrical cables pierced the back of my neck, but I still managed to shout encouragement to the gun’s crews.”

Renown had opened fire at 4:05 amat a range of 18,600 yards; the leading enemy ship returned fire six minutes later; the action lasted six minutes. Renown took two hits but neither caused serious damage. However, she hit Gneisenau three times, destroying her fire control and her after triple turret. The enemy then turned away with Scharnhorst laying a smokescreen.

In the bad weather, Renown found it difficult to keep up. Around 5 amthe enemy ships disappeared into a snowstorm. After 20 minutes the weather cleared, and the German ships were spotted again to the north, but the range had opened. Renown fired again at extreme range but without effect; even at a full speed of 29 knots she could not close the gap, and at 6:15 contact was lost. Whitworth continued on the northerly heading until 8 ambut made no further contact.

By the early morning of April 10, reports were reaching a stunned British government that Oslo had fallen and German troops were swarming ashore in most of the key ports.

The Norwegians, heavily outgunned by the Germans, struck some heavy blows in their defense. At Bergen, coastal artillery damaged the Bremse and Königsberg. South of Oslo things went awry with the landings and coastal artillery and shore-based torpedo tubes badly damaged the Group Five leader, the heavy cruiser Blücher carrying the occupation government; she would later sink.

The assault was called off with command being transferred to Lützow, which had also been damaged in the narrows of Drobak Sound, leaving the capture of Oslo to paratroops that had landed 10 miles away and had to march on the capital. This gave the Norwegian royal family, government, and gold reserves time to escape.

The forts guarding the sea approaches to Oslo were finally taken after heavy raids by Stukas and infantry attacks by air-landed troops. It was only after this that the waterway was opened to traffic.

At Trondheim, Group Two, led by the damaged Hipper, rushed the forts at Brettingsnes at 25 knots and got through to sheltered waters where Hipper used her 8-inch guns to cover the passage of destroyers. Infantry were then landed to attack the forts. While the ships went on to Trondheim, the town offered no resistance and was occupied. By nightfall, however, the forts were still holding out and there was no sign of tankers or heavy weapons for the Army. Also, the vital airfield at Vaernes, 16 miles to the east, had not yet been taken.

Overall, the feeling within the German naval command on the first phase of Weserübung was one of relief—they had gotten away with it. However, the supply situation for the Army was alarming. The “Export Group” that was supposed to be controlling this had gone awry, and the Oslo supply route had come under increasing threat from British submarines. The Norwegian defiance had also come as an unexpected shock.

On Tuesday, April 10, the British chiefs of staff met at 6:30 am, deciding the first priority was to prevent the enemy from cementing their gains in Bergen and Trondheim and sending a battalion to Narvik as a precautionary measure. The War Cabinet did not meet until two hours later, and General Sir Edmund Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, fumed at the delay. Churchill reported on Whitworth’s action and the reality that the Germans were ashore at Bergen and Trondheim. But the Home Fleet was in strength off Bergen, and destroyers were covering Vestfjord to the north.

Ironside emphasized the need to get troops ashore at Narvik and the need to prevent German reinforcements from reaching Bergen and Trondheim; with luck, the Norwegians might be able to retake these towns which the British could then reinforce. The cabinet authorized Churchill to clear the fjords of German vessels and for Ironside to prepare expeditions to Bergen, Trondheim, and Narvik, but to wait until the naval situation was in hand.

Admiral Forbes knew little of this. The Admiralty told him he was to assume that coastal batteries off Bergen and Trondheim were in Norwegian hands. He was to move into the fjords and destroy any German shipping found there, starting with Bergen and, if he had “sufficient means for both,” Trondheim as well.

Forbes gave the job to the 18th Cruiser Squadron with its four cruisers and seven destroyers; the fleet headed south that morning. However, the Admiralty at 11:32 ordered Forbes to postpone the Trondheim operation; at 2 pm it also called off the Bergen operation.

Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, chief of the Naval Staff, had cancelled the operations, feeling they were too risky and thinking better options were to be had. He had already scuppered Plan R4 by sending the cruisers and destroyers to sea to reinforce Forbes. After the midday Cabinet meeting, he told Churchill, who reluctantly agreed.

Forbes and Pound and the men of the Home Fleet were about to pay the price of having inadequate air defense. Although the Oslo had two aircraft carriers training in the Mediterranean, only the Furious was in home waters “working up” after a refit, with her air squadrons disembarked. Thus she put to sea from the Clyde without her fighter squadrons but with the battleship Warspite to reinforce Forbes, who was moving south, just as the Luftwaffe had moved into bases in southern Norway and prepared to attack.

Forbes’ fleet had been found by Luftwaffe reconnaissance aircraft on the morning of Weserübung and that afternoon came under heavy air attack by X Air Corps aircraft flying from bases in Germany. The first attack struck the cruisers as they returned from the aborted Bergen raid. They suffered only minor damage, but the destroyer Gurkha was sunk.

At 3:30 pm, the main body of the fleet was attacked. Again, little damage was inflicted, although the battleship Rodney was hit by a bomb that failed to penetrate her armored deck.

More alarmingly, the fleet had used up a large amount of antiaircraft ammunition but had only shot down one aircraft. In view of this, Forbes told the Admiralty he would concentrate his attack in the north, farther from German bases; the southern area would be left to the submarines.

That night Forbes sent the 2nd and 18th Cruiser Squadrons on a sweep as far south as Stavanger, hoping to catch German reinforcements while he continued north to meet the Furious and mount an attack on Trondheim.

Meanwhile, the Admiralty, over the heads of Forbes and Whitworth and encouraged by Churchill, ordered Captain B.A. Warburton-Lee to take his second destroyer flotilla of five H-class destroyers into Vestfjord and attack the superior German Group One.

They achieved tactical surprise and sank the command ship, the destroyer Wilhelm Heidkamp, and one other, and damaged three more German destroyers; five merchantmen were also sent to the bottom. The five undamaged German destroyers counterattacked, sinking Warburton-Lee’s Hardy and one other; a third was damaged. Warburton-Lee died in the action and was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Petty Officer Neal of the Hardy recalled the sinking of his ship: “She turns over at full speed and sinks…. It is 6:15 amas we abandon ship, and I prepare to leave the wonderful little lady we all love so, love her even now, battered and broken. I am now pretty weak, but I shin down a rope over the side. The cold water revives me. I just make the beach.”

Whitworth sent the light cruiser Penelope and his four remaining destroyers to support the second flotilla, but it was too late. The Admiralty continued bombarding Whitworth with direct orders to attack on April 12; however, the attack planned for that day was called off when Penelope ran aground.

Forbes now sent Whitworth, who had transferred his flag from Renown to the battleship Warspite, into Vestfjord with nine destroyers. It was during this action that Maurice Pacey, flying Warspite’s Swordfish floatplane, sank the U-64. In a fierce battle seven German destroyers were sunk while only two British were damaged.

The Admiralty urged Whitworth to make a landing, but the admiral concluded his handful of Royal Marines and sailors had little chance of dislodging 2,000 German mountain troops in the Lofotens.

Thus the first phase in the battle for Norway came to an end. The Germans had a powerful grip on southern Norway, but in the north their situation was precarious.

The Norwegian situation had started badly and gotten worse. First, the Norwegian government had ordered only a partial mobilization, believing it could negotiate with the Germans. Also, the commander of the Army, General Kristian Laake, tried to avoid confrontation.

On April 10, one of the final acts of the government was to oust Laake and appoint Maj. Gen. Otto Ruge to command the Army. By then, however, the Germans already controlled Norway’s largest cities, ports, and airfields; Ruge could do little other than fight a delaying action until the Allies landed in strength. His main aim was to stop German forces in Oslo from linking up with their forces in Trondheim in the north.

In the south, much of the Norwegian Army had collapsed. Three thousand men of the 1st Division had crossed into neutral Sweden and were interned. At Königsberg and Setesdal large numbers surrendered to the invaders without a fight.

Colonel Thor Dahl, with a mixed group of Norwegian units, tried to hold the area west of Bergen. Ruge called on the troops in the Bergen area to assist Dahl, but they were unable to stop the relentless German advance.

The British, meanwhile, dominated by Churchill and the Admiralty, were patching together their Norwegian strategy as they went along, interfering directly in tactics in the field.

The first British convoy of troops put to sea from the Clyde on April 11; Royal Marines from the cruisers Sheffield and Glasgow were the first British troops ashore at Namsos. Their task was to secure the road bridges and harbor in advance of the landing of Maj. Gen. Adrian Carton de Wiart’s force, known as Operation Maurice. His 12,000 men of the 146th Infantry Brigade and three battalions of French Chasseurs were to attack Trondheim from the north.

The 59-year-old Carton de Wiart, of Belgian and Irish descent, was a heroic British officer, having lost his left eye and left arm during fighting on the Somme in World War I, earning the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for valor. Could his small force stem the German advance?

The advance troops of Carton de Wiart’s force found the Norwegian 5th Division, tasked with defending the area, in a shambles. They had lost all their artillery, and the division amounted to barely 800 troops, having lost many men trying to defend Vaemes airfield.

The German march northward continued on April 14 along two routes—one via Tretten to the junction at Dambas, which would isolate Andaisnes and lead onto Støren and Trondheim. The second was east of the Gudbrondsdal Mountain Range, following the line of the Osterdal Mountains and the valley of Glomna to Roras and then passing through Støren.

Ruge reached his headquarters in the Glomna Valley about noon on April 11. North of Hønefoss the Germans began to meet stiffening Norwegian resistance. Four days later, near Haugsbyyd, the Norwegian 6th Regiment halted the German advance; the defenders were only dislodged with the use of panzers the next day. Maj. Gen. Jacob Hvinden-Haug’s 2nd Field Brigade was deployed across the two routes, but he was unable to halt the Germans on the shores of Mjosa Lake. Elverum, the gateway to the Glomna Valley, fell on April 20.

Due to German air superiority, Carton de Wiart’s troops had to be landed at night by destroyers; around midnight on April 16, a total of 1,000 men were ashore without loss. However, the landing of supplies and heavy equipment would be more difficult.

Troops continued landing the next night but were without transport, artillery, or AA guns. Some units were even short of rations, but they were well kitted out with winter clothing. Carton de Wiart watched his men struggling through the snow in fleece-lined coats and arctic boots, thinking they looked like “paralysed bears.”

The men of the 148th Infantry Brigade, 1st/5th Leicesters had been ordered to Namsos on April 13; the unit had loaded onto the liner Orion at Rosyth when the order was cancelled. Brigadier H. de R. Morgan, the unit commander, received new orders on April 16 to land at Andalsnes instead.

However, the Admiralty had abandoned the use of large troopships that far south, so the infantrymen were loaded onto four cruisers and two destroyers; the force sailed the next morning. Morgan’s new orders were to secure Dombas, then march north against the Germans in the Trondheim area and link up with the Norwegian forces.

The brigade reached Ramsdaisfjord by late evening of April 18, the landings taking place at the ports of Andalsnes and Molde. Morgan, to his surprise and delight, found Colonel H.W. Simpson and a detachment of Royal Marines from the battleships Nelson and Barham and battlecruiser Hood already there. With the three warships then refitting in home waters, the men had been transported in four sloops. Having covered the landing of the main force, the Marines were to hold the landing places and the railhead at Andalsnes. Simpson had a train waiting at two hours’ notice to take some of the brigade to Dombas.

Early the next day, Morgan set off for Dombas with two infantry companies. There he learned the Norwegian cabinet was close to capitulation; the only thing keeping them in the fight was the prospect of British help. Ruge wanted Morgan to move south to Lillehammer to halt the German advance and lift the morale of his troops.

The British plan, Operation Hammer, called for Carton de Wiart’s Maurice Force to move on Trondheim from the north and Morgan’s Sickle Force from the south. Ruge was against the move on Trondheim, arguing that he needed the 148th Brigade to support his men to the south; Morgan reluctantly agreed.

On April 17, Maurice Force had moved inland to Follafoss and Steinkjer. However, on the 20th the Luftwaffe destroyed most of their supplies still stockpiled at Namsos and reduced the town to rubble. Carton de Wiart soon found his troop movements restricted because of aerial attack. The next day they were attacked by the German 181st Division from Trondheim and forced back to Steinkjer.

Sickle Force fared no better as two companies of the Sherwood Foresters took up positions in front of Lillehammer while, on the other side of Lake Mjosa, the Leicesters and the rest of the Foresters took up positions near Gjovik. On April 21, the 4,000-man German 345th Infantry Regiment, reinforced with a motor machine-gun battalion, resumed the advance through Hamar on the east side of the lake.

On the west side, the Allied troops were strafed by German aircraft, and a general retreat was ordered back through Lillehammer with the Leicesters forming the rear guard. They lost their supplies that had arrived at the railway station along with 30 men captured there.

At Faberg, near the mouth of the Gudbrandsdal Valley, Morgan’s troops took up positions to try and keep a river bridge open for retreating troops. He had only four rifle companies available—half of the Foresters were missing. On the morning of the 22nd, they came under fire from artillery and mortars, but the Germans made no major ground attack.

However, in the afternoon, German mountain troops bypassed the position and appeared four miles behind the village, so Morgan had no choice but to order another retreat.

It was the same story at Tretten, where the rear guard was overrun. By the time Morgan’s exhausted brigade retired through Norwegian positions on the night of April 23/24, it had been reduced to nine officers and 300 men.

Hitler was worried over the dangerous isolation of the Trondheim garrison, and he toyed with the idea of the Navy taking troops to reinforce them. He abandoned the idea when Raeder told him it would likely result in the “loss of the transports and the whole fleet.”

Yet German Maj. Gen. Richard Pellengahr, head of the 196th Infantry Division, was well on his way to completing the conquest of central Norway. At Lillehammer, he now had seven infantry battalions, a machine-gun battalion, two artillery batteries, a platoon of tanks, plus two companies of mountain troops pushing forward against weakening resistance.

To his right, moving northward up the Glomna Valley, was a smaller force under Hermann Fischer. By the 25th they were within eight miles of Trondheim and 50 from the garrison perimeter, which, much to Hitler’s relief, showed the end was in sight.

Meanwhile, the British had reinforced Sickle Force with the 15th Infantry Brigade that had landed at Andalsnes on April 23, but suffered the same disadvantages as the 148th Brigade: lack of transport, heavy weapons, and air cover.

The British had tried to redress the balance in the air battle. On April 11, RAF Bomber Command had launched daily attacks from Scottish air bases against the airfield near Stavanger. The day before, 15 Fleet Air Arm Blackburn Skua dive bombers, flying from air bases in the Orkney Islands, sank the damaged cruiser Königsberg off Bergen, the first warship sunk in the war by air attack. Squadrons based in East Anglia also raided the bases of Ålborg and Fornebu.

The RAF also decided to base Gloster Gladiators of No. 263 Squadron on a frozen lake near Andalsnes. Eighteen fighters were embarked on the carrier Glorious and flown in on April 24, a party of ground staff having arrived the day before. Flying from a frozen lake, however, presented its own problems, such as taking two hours to defrost carburetors frozen overnight.

On its first operational day, 263 Squadron flew 40 sorties, reporting six kills. The Luftwaffe soon reacted and caught most of the Gladiators on the ground at night; only four survived, and the frozen lake began breaking up under the impact of bombs. In 48 hours the project was abandoned, and it was left to the carriers to try and combat the German air offensive.

On April 25, Royal Marine Norrie Martin, a flight commander with 810 Squadron, Fleet Air Arm, operating from the carrier Ark Royal, led his section of Swordfish biplanes—the famous “Stringbags”—in an attack on Trondheim airfield.

“On arrival over the airfield at about 6,000 feet,” Martin said, “we could see many fires on the ground, which told us the other squadrons had been there already. We attacked in line astern and were met with fairly heavy and accurate flak.” After dropping his bombs on the hangars, he lost sight of the rest of the squadron.

“I made my getaway and flew down the fjord and out to sea, when I became aware that we were short of fuel and hadn’t enough to get back to the ship. I suppose I had been hit during the attack and the fuel had leaked. Mercifully, I saw a destroyer escorting a merchant ship about 10 miles to the north, so I decided to ditch alongside her.

“I ditched with the aircraft nose-up 70 degrees, and stalled in from about 10 feet. The dinghy came out at once and I stepped in without getting my feet wet. The Stringbag floated for about 40 seconds, and my observer and airgunner clambered over the centre section of the plane into the dinghy.”

Martin and his crew were picked up by the destroyer Maori and taken to Scotland, where they were given a replacement aircraft and flew to the Orkneys to wait for the Ark Royal to return to Scapa Flow.

Once back on board, Martin and his crew were reunited with 810 Squadron, which gave them a “tumultuous welcome,” as they had been “given up for dead.” They were soon back in action, this time bombing the railway line running from Narvik to Sweden.

During the final week of April, the two British carriers, Ark Royal and Glorious, held position 120 miles off the Norwegian coast for five days trying to maintain fighter patrols over Namsos and Andalsnes and support for the ground forces. The Fleet Air Arm fighters shot down 20 enemy aircraft and lost 15 of their own, mainly through accidents. They raided Trondheim several times; however, their influence on the campaign in central Norway was slight at best.

Major General Bernard Paget was put in overall command of the expanded Sickle Force. By April 24, the same day that Paget arrived at Andalsnes, 15th Brigade had moved through Dombas toward Kvam when they ran into the advance elements of Pellengahr’s force.

Rushing to the front, Paget found Ruge in his headquarters 10 miles south of Dombas; he was depressed with little left under his command. Paget was under no illusions over the seriousness of the military situation. Morgan’s brigade was used up, and the Norwegian troops were reaching the end of their endurance. The 15th Brigade was already engaged with an enemy who held all the advantages in weapons and numbers.

His men dug in around Otta. However, by the 27th it was clear a further retreat was required. Paget was determined to keep the road open as long as possible for retreating troops to escape capture while he made plans to hold Dombas. The next morning, though, he received a telegram that the high command had decided on the evacuation of all British troops from Norway.

In the north, the British campaign was based on the capture of Narvik and stopping the Swedish iron ore supplies coming through Norway. Admiral William Boyle, the 12th Earl of Cork, was placed in command of this operation. The ground forces—a mix of British, French, Norwegian, and Polish troops codenamed Avon Force—were commanded by Maj. Gen. Pierse Mackesy.

Mackesy’s Avon Force consisted of the 24th Guards Brigade and French and Polish units. On April 14, Harstad, a town on the island of Hinnoy, had been taken as an advance base. More attention was given to air cover in the north with the deployment of two carrier-transported fighter squadrons that operated from Bardujoss air field.

Boyle and Mackesy met on April 15 when troop convoy NP 1 arrived off the Lofoten Islands, west of Narvik. Boyle wanted to attack straight away. However, Mackesy disagreed, pointing out the ships had not been combat loaded and needed to be reverse loaded so that equipment came off in the right order, something that had adversely affected the landings farther south.

Meanwhile, the Allied retreat from southern and central Norway was proceeding, covered by Norwegian forces who were then demobilized in order to avoid becoming POWs. Sickle Force was evacuated through Andalsnes and was away by 2 amon May 2.

Maurice Force left from Namsos the same day, although delays there meant some of the evacuation took place in daylight, resulting in the loss of two destroyers to Stukas. King Haakon VII and the Norwegian government were evacuated from Molde to Tromsø.

On May 2, Chamberlain announced the evacuation in the House of Commons and came under increasing pressure to stand down. On May 8, he asked for a vote of confidence. Chamberlain lost the vote with even some of his own Conservative Party MPs turning against him. A coalition government was then formed under the premiership of Winston Churchill, who had admitted that the Norway fiasco was his fault, too.

With British attention focused on Norway, on May 10 Hitler sent 136 divisions crashing into Belgium, Holland, and France, swiftly overrunning defensive positions.

But the effort to save Norway was not yet finished. During the night of May 10/11, French troops landed at Bjerkvik to capture the Oyjord peninsula to the north of Narvik on the northern shore of Rombaksfjord. Brig. Gen. Antoine Bethouart commanded the landing force of Legionnaires. The landing was opposed, but with the support of tanks landed from the battleship Resolution the village was soon cleared.

A mile to the east, the village of Meby fell quickly to a second French battalion, but the French troops had learned that their own country had just been invaded.

On the same day, Maj. Gen. Claude Auchinleck arrived at Harstad at about the time the base was heavily bombed by German aircraft. He was there to review the situation and take command if necessary. He found a lack of urgency within the British command and was unable to work with Mackesy, who was ordered back to Britain to report to the War Office.

Auchinleck soon found out the Germans were on the move from Namsos and were nearing Mosjoen. Only the lightly armed and heavily outnumbered Independent Companies under Colonel Colin Gubbins were barring their way. The Scots Guards were moved to Mo to block the advance, and the Irish Guards were ready to support them.

However, the Germans, using great ingenuity, were on the move again, landing 300 mountain troops on the Hemnes Peninsula 50 miles north of Mosjoen and 20 from Mo. The Norwegian force at Mosjøen pulled out. The Allied force at Narvik had to commit significant numbers of troops 200 miles to the south. On May 18, the Scots Guards, coming under increasing pressure, withdrew across Skjerstadfjord covered by the Irish Guards.

A sudden and unexpected Allied victory occurred three days later when French and Norwegian troops captured Narvik while Polish and Norwegian troops advanced to the east, pushing the Germans back to the Swedish border. But on May 25, with the deteriorating situation in France and the Low Countries, the Allied commanders received orders to evacuate from Norway.

Operation Alphabet, the withdrawal of the Allies, had been approved on May 24; the Norwegians were not informed until June 1. Most troops were brought off by destroyers to a safe inshore anchorage and transferred to troop transports. The embarkation was spread over five nights at a rate of 5,000 a night. By the morning of June 7, only 4,600 remained—French and Polish troops on the Narvik peninsula, a small party at Harstad, and RAF ground crews at Bardufoss.

The cruiser Devonshire left Tromsø during the evening of June 7. On board were 461 passengers—mostly British, but also the king of Norway, the crown prince, and members of the government.

The Germans suspected little in the lead-up to the evacuation. Hitler had ordered Göring to make the 7th Air Division available by June 4 to land 2,000 men in the north, in two drops, to retrieve the situation. Admiral Raeder was willing to commit the Navy to the effort, covering the movement of troops to the Tromsø area 100 miles northeast of Narvik. This would include a sweep by the two battlecruisers. However, by June 8, after destroying rail lines and port installations, all Allied troops had been evacuated.

The two British carriers—Glorious and Ark Royal—had been operating off the Lofoten Islands since June 2. Glorious was tasked with embarking RAF aircraft while Ark Royal kept up an intensive flying program, protecting the embarkation and still raiding German positions. On June 7-8, Glorious successfully embarked Gladiators from 263 Squadron and Hawker Hurricane fighters from 46 Squadron. Then her captain, Guy D’Oyly-Hughes, asked permission of Admiral L.V. Wells on Ark Royal to proceed to Scapa Flow independently. Glorious left the coast of Norway in the early hours of June 8, escorted by two destroyers.

Admiral Wilhelm Marschall, commanding the German Fleet sweeping north with his two battlecruisers, the patched-up Hipper, and four destroyers, had sunk three British supply ships and concluded from radio traffic that an evacuation was in progress. Hipper and the destroyers went into Trondheim to refuel.

While he continued north with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on the afternoon of June 8, Marschall spotted Glorious, crowded with aircraft, and her escorts. The destroyers Ardent and Acosta valiantly tried to protect the carrier with suicidal torpedo attacks and laid smokescreens. Ardent was soon sunk, while Acosta managed to hit Scharnhorst in the stern with a torpedo before she, too, was sunk. By this time, Glorious was ablaze and sinking.

There were redeeming factors to this sorry affair. Shortly after Glorious went down, the British submarine HMS Clyde torpedoed Gneisenau, causing heavy damage. This action had also prevented an attack on Admiral Boyles’ lightly escorted main evacuation convoy. On June 10/11, a Norwegian fishing vessel pulled 39 survivors from Glorious out of the water; three later died.

Norwegian forces capitulated to the Germans on June 10, bringing the 62-day campaign to an end. Norway would be subjected to brutal Nazi rule for more than four years. The country was not liberated until May 1945. However, a resistance movement began straight away and would remain active throughout the occupation.

The Norway campaign from the British view was a fiasco, having much in common with the Dardanelles of 1915-1916––hastily conceived and not pressed home with vigor against a ruthless enemy. On both occasions the man issuing the orders was Winston Churchill as First Sea Lord. However, this time, with a twist of fate, rather than going into the wilderness, he became prime minister.

As one historian wrote, the Admiralty lost a “bullying, demanding, impetuous, interfering and administratively incompetent chief; the country gained a defiant, irrepressible, energetic and inspiring leader.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments