By Sam McGowan

In truth, it really was not a combat operation. For every airplane lost to enemy action, a hundred were destroyed in accidents. Yet the effort to resupply Allied forces in China entirely by air was perhaps the most ambitious effort of World War II.

No other effort—including the amphibious landings on beaches from Casablanca to Normandy and from Guadalcanal to Okinawa—faced so many obstacles; obstacles that had to be overcome to simply keep China in the war and prevent the Japanese from overrunning all of Asia. They were obstacles that are as old as human history: rugged mountains, raging rivers, steaming jungles, violent weather—the very features that dictate how regions are settled, trade routes are developed, and wars are fought. These are the obstacles that ultimately dictate how nations and modern military forces develop. Prior to 1942, these obstacles could have never been scaled. Even then, the cost of surmounting them was extreme.

The actual decision to attempt to resupply China by air is lost to antiquity, although developing events in the spring and summer of 1942 dictated that aerial resupply was the only possible means of getting supplies to a country that by that time had been completely cut off from the sea. By mid-1942 Japanese troops occupied China’s port cities and the southern two-thirds of Burma. The Japanese had cut the Burma Road, and Rangoon had fallen into their hands. Thailand, which lay to the south, was allied with Japan, while Japanese troops occupied French Indochina by proxy from the Germans, who now controlled France. The vast Chinese interior remained under Allied control, but with no suitable roads and all of China’s seaports in Japanese hands, the only means of delivering supplies to the region was by air.

As the first country to experience Japanese aggression, China came to depend on the United States as a valuable ally through the efforts of the American-educated wife of the leader of the Koumintang, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Madame Chiang used her American connections to influence President Franklin D. Roosevelt to provide military supplies and other support to her country. Her brother, T.V. Soong, the head of the China lobby in the United States, made sure that Chinese-Americans did not forget their native land and the many troubles facing it. The Soongs found a ready audience for their message in the evangelical Christian movement in the United States, where China had been a focal point of American missionary efforts for nearly a century.

When war finally came to the United States on December 7, 1941, China immediately took on a strategic importance due to its location in relation to Japan. Although events pushed the massive Asian country to the back burner, Allied planners initially saw China as an avenue from which to take the war to the Japanese homeland. American heavy bombers—Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators—could wage a strategic bombing campaign against Japan from air bases in China. In the spring of 1942, the U.S. War Department authorized the establishment of the Tenth Air Force to defend China and begin an aerial offensive against Japan.

Major General Lewis Brereton was transferred from Australia to India to organize an air force that would be made up of a group of heavy bombers, a group of medium bombers, and two groups of pursuit planes, with a troop carrier group to provide air transportation. The famous Doolittle Raid on Japan was actually a part of this plan—18 North American B-25s that had been authorized for China service were diverted by presidential order to make a raid on Japan from an aircraft carrier. The War Department plan called for them to overfly Japan after departing an aircraft carrier in the Pacific, then to proceed on to China. When they got there, the B-25s were expected to form the nucleus of a medium bomber force in China.

It was the impending arrival of the Doolittle force that led to the initial deployment of American transports to India for flights to China. In advance of the raid, 10 Pan American Airways Douglas DC-3 transports operating under contract to the Army Ferry Command were moved from Africa, where they had been supporting British forces, to India. Their mission was to pre-position gasoline and oil at Chinese airfields to service the B-25s when they arrived in China. As it turned out, not a single B-25 arrived intact. The task force was discovered and Doolittle decided to launch the bombers at the limit of their range to even strike Japan. There was little chance that any of them could make China intact. The raid was a propaganda coup for the Roosevelt administration, but the loss of the B-25s and the subsequent capture of the proposed sites for bomber bases destroyed Allied plans for mounting an air campaign against Japan from China in 1942.

Even as the Doolittle raiders were on their way to China aboard the aircraft carrier Hornet, Colonel Caleb V. Haynes was on his way to India via the overland route across Africa and Central Asia with a combined flight of Boeing B-17s and Douglas C-47 transports. Haynes’s force, which was designated as Project Aquilla, was to serve as the nucleus of a heavy bomber force in China. These planes were to join a bombardment group that was being transferred from Australia. (The 7th Bombardment Group had fought in Java and the Philippines—its small force of B-17s and LB-30 and B-24 Liberators had been greatly diminished.)

Another force of B-24s under Colonel Harry Halverson was also planned for China, but its departure from the United States was delayed, and the Halpro force ended up diverting to the Middle East where it would eventually be joined by the Aquilla B-17s. Haynes and his men arrived to discover that the military situation in China had taken a turn for the worse as the Japanese went on the offensive in retaliation for the Doolittle Raid. The planned bomber bases had been overrun, and Japanese forces were advancing into Burma. Haynes and some of his crews gave up their B-17s and were put to work with the C-47s hauling supplies into Burma. As the military situation deteriorated, they evacuated Allied troops from the country.

Unfortunately, the Japanese were successful in both Burma and eastern China, leaving the Allies completely landlocked. Although Chinese forces held the vast interior of the country, the only means of delivering supplies was from India. Even without the threat of enemy action, land delivery was extremely difficult due to the rugged terrain of eastern India and central Burma, but even that possibility was ruled out when Japanese forces cut the Burma Road. With the land routes cut, the only means of delivering supplies to China was by air.

By the spring of 1942, it was apparent that delivering supplies to China was to be a major mission of the Tenth Air Force, the organization the War Department had created for control of air operations in the China-Burma-India Theater. With the loss of the planned bomber bases, China also lost its importance to the strategic plan, but there was one element that dictated that the country could still be important to the Allies.

Chennault’s ‘Flying Tigers’ Evolved into an Air Force Deep in the Chinese Interior

Before the war, retired U.S. Army Captain Claire Chennault had organized an all-volunteer air force staffed by former U.S. military personnel to support China. The American Volunteer Group went into action two weeks after Pearl Harbor and immediately revealed to the world that Japanese air units were not invincible. Chennault’s small force of fighters, known as the Flying Tigers, would evolve into an air force operating deep in the Chinese interior, a force that would tie down Japanese air units in Southeast Asia, preventing some of them from moving to other theaters. Chennault was recalled to active duty as a brigadier general and given command of the China Air Task Force (CATF), a subordinate unit to Tenth Air Force. The CATF would be entirely dependent on airlift for everything it needed to function as a viable combat force.

When it became obvious that air resupply of China would be a major Allied mission in the CBI, the War Department authorized the creation of a special transport unit to move supplies from India to China. In March 1942, Project Ammisca, a special effort consisting of a “ferry” force made up of a hundred recalled Army reservists, mostly active airline pilots, was formed. The reservist pilots reported to the Ferry Command base at Morrison Field, Florida, where they joined enlisted crew chiefs and radio operators. Formed in 1941 to provide crews on temporary duty from the Air Combat Command to ferry U.S.-built aircraft sold under Lend-Lease to the Allies, Ferry Command had no other operational mission.

However, just prior to the war, the command was authorized to contract with the airlines for aircraft and crews to set up a “ferry” of supplies to British forces in North Africa. So, the mission of delivering supplies to China was given to it. The situation became even more complicated when the War Department decided that the “India-China Ferry” should be a Tenth Air Force responsibility. The original plan called for Ammisca to be under the direct control of General Joseph Stilwell, the senior Allied officer in China, but Tenth Air Force commander Brig. Gen. Clayton Bissell naturally believed that if he was to be responsible for the air ferry, all of the assets involved should be under his command.

Ammisca commander Brig. Gen. Robert Olds, an original member of the Ferry Command staff, opposed the transfer, but Bissell’s view won out. When Ammisca arrived in India as the 1st Ferrying Group, it became part of the Tenth Air Force.

There was a third air transportation entity in Asia, one that offered perhaps even more possibilities for success than the 1st Ferrying Group. China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) was a subsidiary of Pan American Airways, which had been established in China in the 1930s. Many of the pilots were former U.S. military fliers—including some who joined the airline after leaving Chennault’s AVG—and they took quickly to air transportation operations in the rugged conditions faced along the routes to China. CNAC would be the prime element in the China Ferry for most of 1942.

Brigadier General Earl Naiden surveyed the route for the Assam-Burma-China Ferry, along with a Trans-India route from Karachi to the Assam Valley, from which supplies bound for China would depart. The most direct and efficient route was across Burma to the airfield at Myitkyina on the Burma-China border, where supplies could be transferred to river barges then to trucks for the remainder of the trip to Chungking and Kunming. But Myitkyina was a strategic target for Japanese forces in Burma, which captured the airfield on May 8, placing the success of the resupply effort to China in doubt.

From Myitkyina, Japanese fighters threatened to control Burmese skies while their bombers were in easy range of the Indian bases from which the airlift was to be mounted. To alleviate the threat to India and reduce Japanese efforts against the air routes to China, the Tenth Air Force made the airfield at Myitkyina its primary target.

The delivery of supplies to China attracted political attention at the highest level of the United States government as President Roosevelt took a personal interest, to the extent that he actually set monthly tonnage goals. Had simply flying supplies into China been the only military consideration in the CBI, the goals might have been met. Unfortunately, Japanese troops were moving westward, forcing the Tenth Air Force to prioritize the use of its forces, with the defense of India becoming primary.

Air transportation was proving to be a major asset to ground operations in the theater, as well as in New Guinea in the Southwest Pacific where Allied forces faced similar obstacles. Military considerations for the defense of India led to frequent diversions of 1st Ferrying Group transports to missions in support of combat operations. Every time a transport was assigned to another mission, one less airplane was available for the China Ferry.

Sinclair’s Scathing Report of the 10th Air Force Accused Them of Having a “Defeatest Attitude” and Lacking a “Singleness of Purpose”

Political interest in the delivery of supplies to China ran high, thanks in no small measure to the interests of the American companies selling war materials to the Chinese. Their representative company was China Defense Supplies, Inc., a corporation that had been formed by Whiting Willauer, a New York lawyer with political connections, to act as a middleman between the Chinese government and the U.S. manufacturers for the delivery of Lend-Lease supplies. Willauer was also instrumental in the formation of the AVG. Payment for materials was contingent on their delivery to Chinese soil, and executives whose companies stood to make millions from the supply effort were not sympathetic to the military problems of the region.

A China Defense Supplies, Inc., representative, one Frank D. Sinclair, who wore the title of “Aviation Technical Advisor” in the company, visited India in the summer of 1942 to observe the airlift. Sinclair, whose background was in the aviation industry and who had airline connections, wrote a scathing report accusing the Tenth Air Force of having “a defeatist attitude” and lacking “singleness of purpose” in regard to the China Ferry. Sinclair’s accusations seem ridiculous today when considering the seriousness of the military situation in eastern India in 1942, which he either failed to grasp or chose to ignore. Nevertheless, the report attracted the attention of the White House. A copy also went to the headquarters of the infant Air Transport Command.

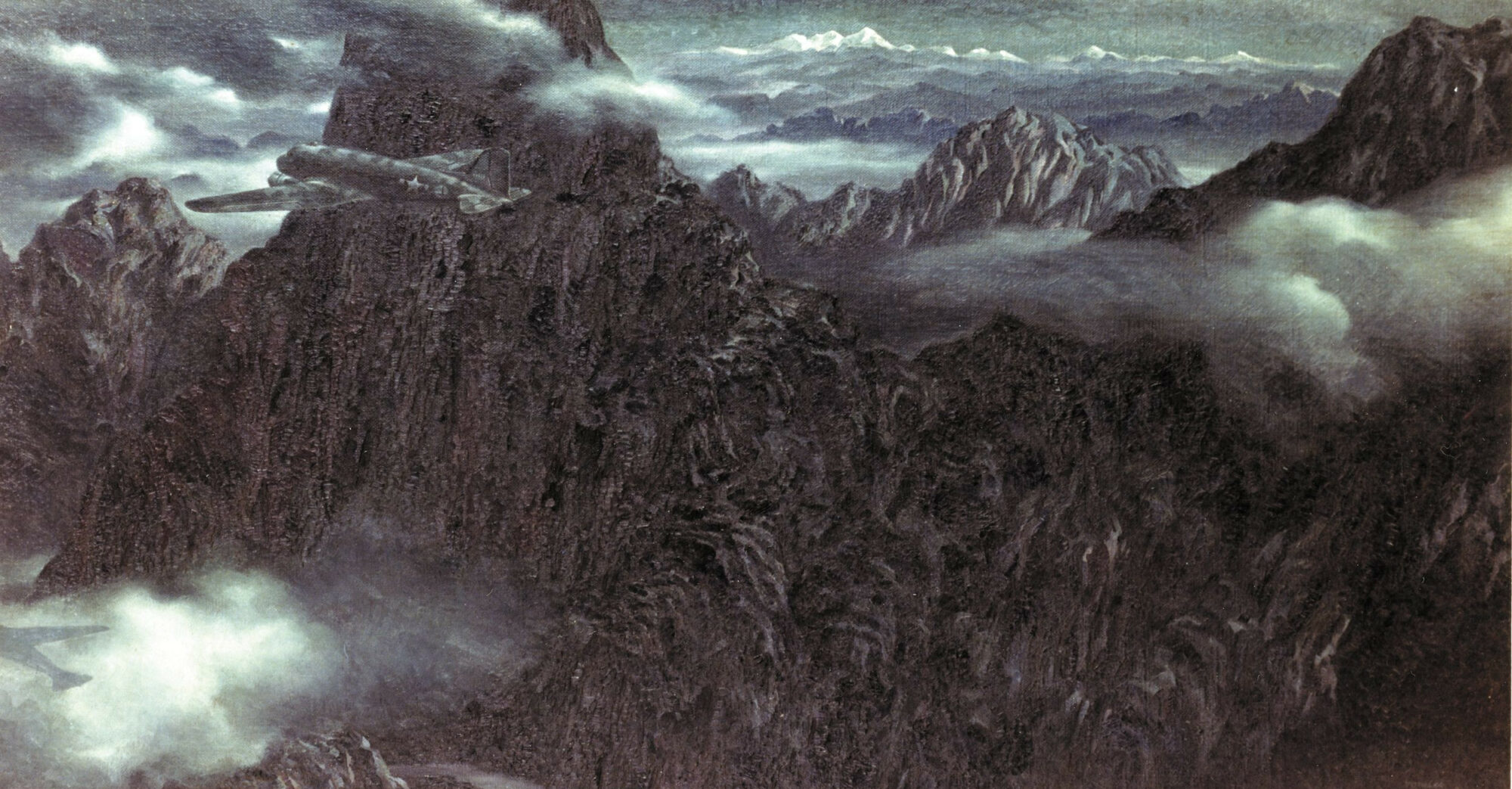

In reality, the effort to deliver supplies to China was proceeding in spite of numerous problems, the most serious of which was the loss of Myitkyina. With the central Burmese airfield no longer available for transshipment, transports were forced to fly all the way to Kunming to deliver their loads, which reduced the efficiency of the transports and the amount of supplies that could be delivered. Furthermore, the threat of interception forced the unarmed transports to fly a more circuitous route, heading north over the eastern reaches of the Himalayas, then turning east to their Chinese destinations. Although the high Himalayas were well to the west, the “foothills” north of the Assam Valley were higher than the American Rockies.

The combination of humid air masses moving north out of the Bay of Bengal and the high mountain elevations produced some of the worst weather conditions in the world—strong winds that made navigation difficult, violent thunderstorms with heavy rain, and severe mountain turbulence that could rip an airplane apart. In the higher elevations the rain turned to ice and snow, which could load the wings and force an airplane into the mountain peaks.

Consideration was given to placing the entire responsibility for the movement of supplies to China on the China National Aviation Corporation, a move that Stilwell opposed. He believed it would be a mistake for U.S. military personnel to be under the control of an organization whose civilian personnel were paid on a much higher scale. Stilwell proposed instead that the CNAC be contracted to the Tenth Air Force, a suggestion accepted by the War Department and by the Chinese government, which owned the airline. The CNAC transports were assigned exclusively to the movement of supplies from Dinjan to China.

The airlift got off to a slower start than the White House wanted, but it was a start nevertheless. The CNAC transports in particular soon established an efficient routine. But the 1st Ferrying Group effort suffered innumerable problems, thanks in part to the diversions of some of its airplanes—one squadron was diverted to the Middle East in June. Only about two-thirds of the group’s assigned airplanes had reached India by mid-1942. Quite a few were involved in accidents during the move while others were diverted to support military operations in Africa and the Middle East. Once they began operations, the transport force was plagued by accidents.

Events in the spring of 1942 eventually affected the China Ferry, although not until late in the year. Lawrence Pogue, the director of the Civil Aeronautics Board, wrote a letter to President Roosevelt expressing his concern that the haphazard awarding of military contracts to the nation’s airlines was detrimental to the future of the industry. Pogue’s solution was the creation of a pseudo-military government-run airline reporting directly to the president, an airline that would function independently of the Departments of War and the Navy.

A second alternative was for the War Department, at least, to set up its own air transportation command to handle airline contracts. A board of military officers was appointed to consider the problem, but before it submitted a solution Army Air Forces commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold took matters into his own hands. On June 20, Arnold issued General Order No. 8, establishing an Army air transportation organization that would be responsible for all air transportation needs except those directly related to combat.

The order took the “air transport” designation that had previously belonged to the groups and squadrons that had been formed to support combat operations and gave it to the new organization. The former air transport units were redesignated as “troop carriers.” The reorganization also transferred the responsibility for issuing military contracts to the airlines from the Air Service Command to the new Air Transport Command.

The Air Transport Command was assigned a dual function, the ferrying of military aircraft, including Lend-Lease aircraft that had been consigned to other nations, from factories to combat units and the transportation of military cargo and passengers. As such, it was divided into two sections, the Ferrying Division and the Air Transportation Division. To staff the new command, the Army drew heavily on the airline industry, which contributed a number of key personnel who were given direct commissions as field grade officers. American Airlines President Cyrus R. Smith was assigned as the chief of staff of the new ATC, initially with the rank of colonel and with the responsibility of organizing and supervising the Air Transport Division.

Both divisions depended heavily on the national airline industry for contract pilots and air crews as well as for former airline personnel to fill military positions. The Air Transport Command also utilized “service pilots,” men with civilian flying experience who were brought directly into the military without undergoing military pilot training. ATC’s Ferrying Division also included a sizable number of female pilots, women with civilian flying experience who were employed in the same manner as male civilian contract pilots with the exception that their activities were confined to North America.

A copy of the Sinclair letter ended up in the hands of ATC Chief of Staff C.R. Smith, who saw and seized an opportunity for his new command and for the airline he managed in civilian life. He elaborated on Sinclair’s complaints to assert that an independent command should be established in the CBI for the sole purpose of delivering supplies to China. Smith proposed that the Air Transport Command “take over” the airlift of supplies to China. His rationale was that since the Air Transport Command was made up of “air transportation professionals,” it would logically be able to produce a better product than the Army’s combat command.

All that would be required, according to Smith, would be support from the theater units in the form of base facilities and the air bases from which the ATC transports would operate. ATC would do the rest. Smith made a powerful case, and his proposal was accepted by General Stilwell. The ATC was to take over the airlift to China on December 1, 1942. Unfortunately, Smith’s proposal was founded to a large degree on wishful thinking, and his command would not only fail—it would fail miserably.

Crews Flying “The Hump” Faced Constant Danger From Enemy Attack and Reduced Aircraft Performance Due to the Rarified Air

The “Hump” that ultimately gave the airlift its name was the Santsung Range, a long ridge that reached 15,000 feet in places and lay between the Salween and Mekong River valleys on the Burma-China border. Fortunately, Allied troops, mostly native Ghurkas and Chinese, held northern Burma, thus affording advance bases for Tenth Air Force fighters charged with protecting the airlift route. Allied fighters and bombers concentrated on Japanese airfields in Central Burma, reducing Japanese fighter capabilities and allowing more direct deliveries from the transport bases in India’s Assam Valley to the destination airfields at Kunming and Chungking.

Even though the threat of enemy air attack was sporadic, the crews flying the Hump faced constant danger, not the least of which was the reduced performance of their aircraft in the rarified air at the airfields themselves. Many of these were located at altitudes several thousand feet above sea level. In six months in 1943, Air Transport Command suffered no less than 134 major accidents on the Hump route, a large number of which occurred during takeoff and landing.

In spite of Smith’s assurances that ATC would increase airlift capabilities over the Hump, tonnage amounts actually declined during the first months after the transfer. The decline came in spite of an increase in the size and perceived capabilities of the airlift force. When ATC took over the Hump operation, it began making plans to add new types of aircraft to replace the Douglas C-47s with which the 1st Ferrying Group was equipped. In early 1943 a contingent of Consolidated C-87 four-engine transports arrived in India. C.R. Smith’s own company, American Airlines, provided the flight crews under contract.

The transport version of the B-24 Liberator bomber, the C-87 promised to increase tonnage capabilities considerably due to its increased payload. However, it failed to live up to initial expectations. The other new type assigned to the Hump operation was the Curtiss C-46 Commando, a large twin-engine airplane capable of carrying a much larger payload than the DC-3 and C-47. But the C-46 was poorly designed, particularly the fuel system, with miles and miles of aluminum and steel tubing that made the airplane a mechanic’s nightmare. Fortunately, modifications to the design turned the C-46 into an adequate transport, although it never lived up to expectations.

Although ATC had promised to increase the airlift tonnage, it would take the India-China Wing another six months to attain the 4,000 tons a month goal it had promised for February 1943. Meanwhile, the White House and War Department were promising tonnage levels twice those that were actually being carried. For example, the goal for September 1943, when tonnage finally exceeded 4,000 tons, was 10,000 tons. The Air Transport Command commander, Maj. Gen. Harold George, passed the buck to the Tenth Air Force, claiming that the India-China Wing was “a relic” of the 1st Ferrying Group that had been transferred to theater command over the protests of the Ferry Command leadership. Such an argument doesn’t hold water. In reality, other units involved in airlifting cargo to China were constantly increasing their capabilities.

By September 1943, the CNAC was averaging 49 tons per airplane per month, while ATC squadrons were only carrying 23—and this in spite of the fact that ATC was equipped with C-87s and C-46s, both of which afforded considerably larger payloads than the CNAC DC-3s. Furthermore, when the 1st and 2nd Troop Carrier Squadrons became operational in India in the spring of 1943, they immediately became far more efficient than ATC. Many of the crews in the two troop carrier squadrons, which were promised to the Tenth Air Force as compensation for the loss of the 1st Ferrying Group, were fresh from training in the United States. Obviously, the problems with the India-China Wing were internal.

Eastern Airlines president and World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker paid a visit to the CBI in the spring of 1943. With decades of experience in air transportation, Rickenbacker recognized that the real problem with the airlift lay in the command organization. The Air Transport Command was attempting to operate an independent command within a combat zone while expecting to receive priority support from a theater command that was up to its ears in combat operations.

Rickenbacker also noted the lack of suitable airdromes to handle the airlift operation, as well as shortages in weather forecasting, communications, engineering, and maintenance personnel. To Rickenbacker, the only logical solution was to return responsibility for the airlift operation to the Tenth Air Force. Rickenbacker’s views were not shared by those within the military establishment in Washington, especially the leadership of the Air Transport Command. The airlift remained under ATC. The problems continued.

Low morale was a major problem in the ATC units in India, although they were operating under conditions no worse, and perhaps better, than those endured by the combat squadrons. For Americans native to the temperate United States, the heat and humidity of India were a shock. They made life miserable, and they also produced torrential rains that turned the bases into seas of steaming mud. The situation was compounded by the presence of venomous snakes, insects, and vermin of every description.

Another factor unique to ATC personnel that is not discussed in histories of the airlift was the feeling that hauling freight to China was less important than fighting the Germans and Japanese. While the Ammisca pilots were drawn from the ranks of the U.S. airlines, they were also U.S. Army reservists and trained combat pilots. They knew that other reservists had been assigned to the bomber squadrons that were being formed in the United States, often in positions of leadership as flight and squadron commanders. Yet, here they were, pushing freight in unarmed transports in a backwater region of the world.

The lack of the exuberance of youth was also a factor. As a rule, ATC pilots in 1942 and 1943 were considerably older than the young men assigned to the combat squadrons. An older man’s ordeal is often a young man’s adventure. It is worth noting that the efficiency of the airlift began to improve after more and more Army pilots became available for transport duty.

Combat Crews Derided the ATC Crews, Referring to the ATC Acronym as ‘Allergic to Combat’

The Air Transport Command took several steps in an attempt at improving the morale of the airmen assigned to the Hump mission. A major complaint was the poor delivery of mail, so mail was assigned a higher priority in the cargo system. General George convinced the Army Air Forces to authorize the awarding of combat decorations, particularly the Air Medal and Distinguished Flying Cross, to Hump flyers even though the dangers they faced were more from weather conditions and adverse terrain than from an armed enemy. He also obtained a citation for the India-China Wing.

The ATC headquarters encouraged several well-known media representatives to observe command operations, including the Hump airlift. Photographs and articles produced by men such as Ivan Dmitri appeared on the pages of Time, Life, and The Saturday Evening Post. The publicity drew attention to the role of the ATC airmen, but it also led to derision among the combat crews—especially troop carrier personnel—who began referring to the ATC acronym as “allergic to combat” or, in reference to the civilian contract crews, “Association (of) Terrified Civilians.” The hostility toward ATC also reached into the command levels in the combat units, as theater command personnel came to believe that the ATC leadership in Washington was out to build an empire at their expense.

In mid-1943, the Army increased the size and capabilities of the India-China Wing of the ATC more than fivefold, a factor that allowed tonnage levels to finally begin increasing. Additional air bases were placed into service in India’s Assam Valley and in the Chinese interior to handle the vastly increased airlift apparatus. All of the ATC wings were elevated to division status, including the India-China Wing, which became the India-China Division.

In September, Colonel Thomas O. Hardin transferred to the India-China Division to take command of the Hump operation. An airline executive in civilian life, Hardin had a reputation as a hard driver. He was also a practical commander who realized that official policies were often detrimental to mission completion. One of Hardin’s actions was to implement 24-hour-a-day operations on the Hump route, thus greatly increasing the number of flights each day. The additional flights immediately increased tonnage capabilities over the Hump. In December, Hump crews hauled more than 12,000 tons into India. Adverse weather and high terrain made night operations more dangerous, and the accident rate increased.

The ATC leadership realized that an essential ingredient in the success of the airlift was an adequate supply of aircraft and engine parts. General George authorized special weekly flights from the Air Service Command supply depot at Fairfield, Ohio, to India. Four C-87s from the 26th Transport Group began the operation in September, but the mission transferred to the Ferrying Division in November and became known as Fireball. To keep the airplanes moving, crew stage bases were set up along the route. The rapid deliveries of aircraft parts also increased the numbers of available operational airplanes.

Although the threat of enemy interception was real, there were actually very few instances when ATC transports were subjected to enemy air attack. The worst period for the ATC, and other crews flying the Hump, commenced on October 13, 1943, when Japanese fighters operating from forward fields in central Burma attacked Allied aircraft over northern Burma. Two transports, a C-46 and a C-87, were shot down that day along with a CNAC DC-3. A B-24 and two Tenth Air Force C-47s were damaged. The Japanese were in for a surprise when they attacked several armed B-24s that were engaged in transport operations, and paid for their mistake with several losses.

Over the next two weeks two more ATC transports were shot down, and three others were reported missing. Two more transports were shot down in December. These were the only ATC combat losses on the airlift to China. Statistics reveal losses to enemy action of seven transports and 13 crew members during the duration of the Hump Airlift.

Even though losses to enemy action were minimal, Hump airplanes and crews were being lost to accidents at a phenomenal rate. So many wrecks were strewn along the route from Assam to Kunming that some Hump crews began referring to it as “The Aluminum Trail.” Still, the majority of the accidents occurred at the airfields themselves, where the combination of higher elevations and hot temperatures put the transports on the very edge of their operational performance envelope.

The accident rate was particularly high among the four-engine C-87s, no doubt due to the lack of adequate runway lengths for the altitudes involved. The Army had established 6,000 feet as the necessary runway length for a loaded C-87, apparently without taking into consideration the phenomenon known as density altitude. Due to high temperatures, density altitude—the altitude that actually effects an airplane’s performance—is significantly higher than the actual elevation, thus increasing takeoff distance considerably. Climb performance is also drastically affected, meaning that the loss of an engine right after takeoff on a hot day in high terrain was a sign of impending doom. It is reported that accidents during the Hump airlift claimed some 600 transports and the lives of 1,000 airmen.

In the spring of 1944, the capabilities of the ATC Hump airlift force were greatly increased with the arrival of additional C-46s that were dedicated to the support of Matterhorn, a special unit equipped with long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers to begin aerial operations against Japan. The Twentieth Air Force deployed to China as a self-sufficient unit. Several XX Bomber Command B-29s were converted into tankers to transport fuel from India to the advance bases in China from which the Superfortresses would depart on missions against Japan.

The Matterhorn force also included its own transport squadrons equipped with C-87s and a new transport version of the Liberator, the C-109 tanker, which entered service in August. While the C-87 was essentially a B-24 that had been stripped of the features that made it a bomber and equipped with a cargo floor, the C-109 incorporated a system of tanks that could be filled with fuel. Both the C-87 and C-109 were designed so that ground crews could drain extra fuel from their tanks at the Chinese bases. Aviation fuel was the major commodity delivered over the Hump, especially in 1944 and 1945.

Support of the Matterhorn force greatly increased the amount of tonnage being hauled across the Hump by the India-China Division. The division received a bonus when XX Bomber Command agreed to transfer its C-87s and C-109s to the Air Transport Command. When the War Department decided to withdraw the B-29s from China in early 1945, the transports that had been dedicated to their support were incorporated into the Hump airlift. It was largely due to the increase in airlift capability that ATC was able to start exceeding its monthly tonnage goals.

In August 1944, Brig. Gen. William H. Tunner replaced Brig. Gen. Thomas O. Hardin as commander of the India-China Division. Tunner was an ATC veteran whose air transport career dated to his assignment as the personnel officer for the Ferry Command before the war. When the ATC was activated, Tunner was placed in command of the Ferrying Division. One of the first production-oriented officers of the Army Air Forces, Tunner achieved a reputation for organization and safety. The India-China Division set unprecedented records while under Tunner’s command, records for which the general was quick to take credit. Many historians credit Tunner with “turning around” the airlift, and the modern Air Mobility Command considers him to be “the father of Military Airlift.” Such, however, is not the case.

The ATC Effort had Fallen Short of its April Allotment by More Than 4,000 Tons, Causing the Assignment of More Aircraft and Crews and Leading to a Great Deal of Resentment Towards the ATC.

Several factors led to the increase in tonnage being airlifted to China, not the least of which was the capture of the airfield at Myitkyina by Merrill’s Marauders in May 1944. Although the town itself remained in Japanese hands until August, the capture of the airfield had a two-fold benefit for the Hump airlift. It deprived the Japanese of an advanced base for their fighters and afforded the ATC a delivery point from which supplies destined for China could be further delivered by truck and barge.

The reduction in the threat of enemy interception allowed ATC crews bound for China to take a more southerly route over lower and less hostile terrain. The lower altitudes now required for flights into China allowed the introduction of the four-engine Douglas C-54 Skymaster to the airlift. Although the C-54 had proven to be a reliable transport with substantial payload capabilities, its limited high-altitude performance ruled it out for flights over the Hump. The C-54 also had a far better safety record than the C-87, although this was perhaps largely due to the Douglas transport being operated at lower elevations than the Liberator Express. However, it was C-46s, not C-87s, that the C-54s began replacing.

Tunner took command in India just as the size of the India-China Division was greatly increased by the transfer of the XX Bomber Command transports to ATC. The combination of an increased force and shorter routes at lower altitudes from India to China naturally resulted in an increase in the amount of cargo carried.

Although Tunner has been given too much credit for the success of the Hump airlift during its final year, he did implement new maintenance and cargo-handling procedures that improved efficiency. One of his first actions was the introduction of what he called “Production Line Maintenance,” a system under which airplanes were placed on a line not unlike an assembly line over which they moved as various maintenance items were completed. Under previous procedures, a crew of men would complete all required maintenance procedures one airplane at a time.

Tunner’s system allowed more specialization as individual mechanics concentrated on specific tasks. He also applied similar techniques to the processing, handling, and loading of cargo. Due to the increase in size of the airlift force and the decreasing military urgency, Tunner was also able to institute safety policies in an attempt to lower the accident rate.

Tunner also benefited from the Allied successes in Europe and elsewhere in the Pacific Theater. By the time he took over the India-China Division, Allied troops were advancing from the Normandy beachhead and, most important, the air war in Europe had been won. The decreasing demand for replacement pilots in heavy bomber groups made more four-engine pilots, aerial engineers, radio operators, and navigators available for transport duty. The reduced demand for trained aircrews in the combat groups led to a reduction in primary flight training, thus releasing the staffs of the hundreds of primary flight schools for military service.

Tunner and the India-China Division also benefited from decisions made by the Army Air Forces as the war in China began winding down. By the spring of 1945, Burma had been liberated, and the massive troop carrier and combat cargo organization that had been developed to support combat operations in the CBI became available for routine transport operations.

Lieutenant General George Stratameyer, the senior American air officer in the CBI, made another decision that greatly increased ATC capabilities. He and his staff decided that the cost in fuel of conducting heavy bomber operations from bases in China was prohibitive and that the four-engine B-24 Liberators of the 7th and 308th Bombardment Groups would be more productive in transport operations than in tactical operations.

In May, Stratameyer ordered the transfer of the two bombardment groups, the 433rd Troop Carrier Group, and the 3rd and 4th Combat Cargo Groups to the operational control of the India-China Division of the ATC. The transfer was not based solely on efficiency. The ATC effort had fallen short of its April allotment by more than 4,000 tons, and the assignment of more aircraft and crews would boost ATC capabilities.

The transfer met with resentment on the part of the combat personnel, who saw their new assignment as degrading. That they had to undergo a week of training under the supervision of ATC personnel caused further resentment among the bomber and troop carrier crews—all of whom were veterans of months and sometimes years of Hump operations. Ironically, the troop carrier and combat cargo squadrons had been carrying considerably more tonnage across the Hump than ATC. In March 1945, troop carrier and combat cargo transport delivered twice the tonnage transported during the same period by ATC.

The former combat aircrews were now under the control of “Tonnage” Tunner, and the India-China Division commander insisted that the combat crews undergo the same training as newly assigned crews fresh from the United States. In spite of their resentment and subsequent low morale, the bomber and troop carrier/combat cargo crews made a large contribution to the airlift to China through the end of the war. It was only due to their contribution that the India-China Division was able to exceed 50,000 tons a month.

With the end of the war, the requirement for the airlift of supplies to China lessened. The airlift continued, however, until November as Allied forces in China moved into occupied territory formerly held by Japanese troops.

Sam McGowan is himself a pilot. He resides in the Houston, Texas, area.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments