By Michael D. Hull

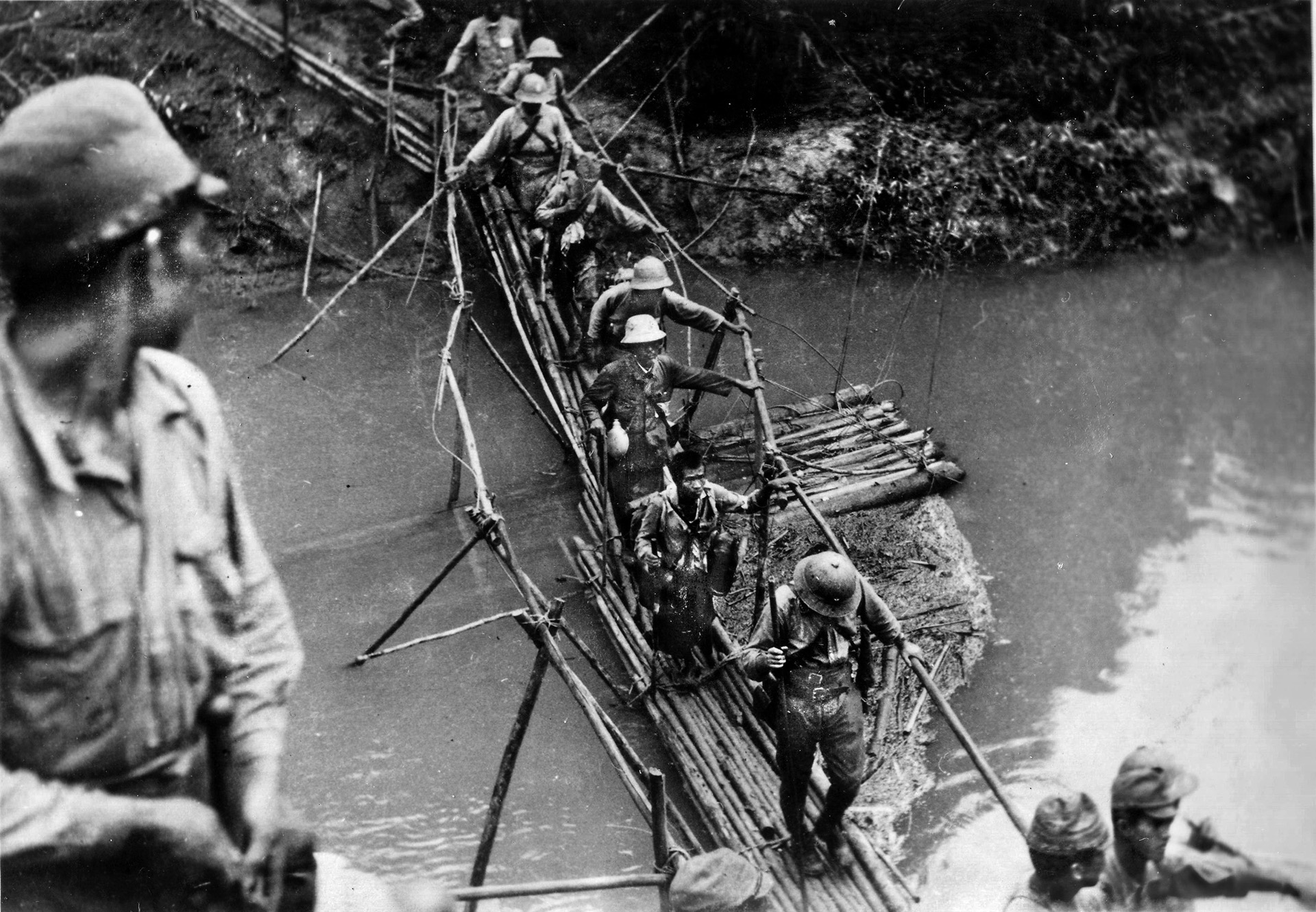

One ominous day in mid-May 1942, Lt. Gen. William J. Slim stood on the Imphal Plain, high in the Assam hills of northeastern India, and watched columns of tattered, malaria-ridden British, Indian, and Burmese soldiers straggle across the frontier from Burma.

They were the remnants of his 1st Burma Corps (Burcorps), ending a 900-mile retreat ahead of pursuing Japanese troops and a monsoon. The two-division, 42,000-strong corps had lost 13,000 men killed, wounded, and missing, and it had only 28 field guns left out of 150, and 80 trucks and jeeps out of several hundred. It was one of the longest and most disastrous withdrawals in the history of British arms.

The burly, bulldog-jawed “Bill” Slim anguished over the pitiable condition of his men. Gaunt and exhausted, they nevertheless carried their arms and kept their ranks. “They might look like scarecrows,” the general observed proudly, “but they looked like soldiers, too.” He had skillfully extricated them from near disaster in the steaming jungles of Lower Burma. Slim was familiar with defeat and had no illusions about the wily, tenacious enemy who had captured most of the country.

“We, the Allies, had been outmaneuvered, outfought, and out-generaled,” he said. Yet he was sure that, with special training and renewed spirit, his troops could eventually prevail in the most forbidding theater of operations in World War II.

“To our men, British or Indian, the jungle was a strange, fearsome place,” said Slim. “Moving and fighting in it was a nightmare. We were too ready to classify jungle as ‘impenetrable’…. To the Japanese, it was the welcome means of concealed maneuver and surprise … We used troops whose training and equipment, as far as they had been completed, were for the open desert…. The Japanese reaped the deserved reward for their foresight and thorough preparation; we paid the penalty for our lack of both.”

As commander of the newly formed British 14th “Forgotten” Army, Slim was to march back and, after two years of bitter fighting, liberate Burma and inflict on the Japanese their greatest land defeat of the war. Trusted by his men and admired by allies, Slim emerged as one of the great British commanders of the 1939-45 war. Yet he was denied the credit he deserved.

On his return to England in 1945, the modest, understated campaigner met a lukewarm reception. Field Marshals Harold Alexander and Bernard L. Montgomery were the men of the hour. When books appeared about Lord Louis Mountbatten, Maj. Gen. Orde C. Wingate and his Chindits, General Joseph W. Stilwell, and other luminaries of the campaigns in Southeast Asia, Slim was accorded only footnotes.

And it was the same story when the documentary film Burma Victory was released in November 1945. Directed by Roy Boulting, whose Desert Victory (1943) was hailed as the finest documentary of the war, the first 50 minutes of Burma Victory focused on Mountbatten, Wingate, Stilwell, and General Sir Oliver Leese, while Slim made a brief appearance in the film’s last 10 minutes. Veterans of the 14th Army who watched it were puzzled and appalled. They knew that their commander was responsible for the real-life Burma victory.

A ranker from modest origins, Slim was different from Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s favored generals, such as Alexander, Wingate, Alan Brooke, and Claude Auchinleck. He had not attended public schools, was not a scion of the Anglo-Irish ascendancy, and could not trace his unimpressive family name back into the annals of the Norman conquest, as could Montgomery and Archibald Wavell. After the Singapore surrender and many other early defeats at the hands of the Japanese, Churchill had a low opinion of his captains in the Far East, and it took him some time to realize Slim’s worth.

Born in Bristol, Somerset, on Thursday, August 6, 1891, William Joseph Slim was the son of a middle-class Birmingham wholesale ironmonger. A bright, sturdy lad, he gained a scholarship at the local grammar school and joined its cadet corps. His first job in 1909 was as an uncertified teacher at elementary schools in the Birmingham slums, followed by a post as junior clerk in a metal-tubing firm. He read popular military histories and considered an army career.

Sandhurst and a commission were out of his reach, so in 1912 he enrolled in the Officer Training Corps at Birmingham University, a Territorial Army unit. On August 22, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, Bill Slim was gazetted a second lieutenant in the 9th Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment. He had escaped from the dreary routine of office work, and, like his former OTC comrades, greeted the war with enthusiasm. But most of them would not survive it.

The regiment was posted to Mesopotamia and then took part in the ill-starred Dardanelles campaign the following year. Bill Slim’s baptism of fire came during the bitter struggle at Gallipoli and Cape Helles, where fierce Turkish resistance pinned down British and Australian troops on the beaches. He marked himself as an outstanding junior officer and proved his courage by leading headlong bayonet charges against the well-entrenched enemy during 18 days of intense fighting in July-August 1915. He was severely wounded on August 8 and was evacuated to England.

The wounds should have crippled him for life, but he overcame them with his physical and moral stamina during almost a year of recuperation. Gazetted a temporary captain in September 1916, Slim transferred to the West India Regiment, a regular unit, and was posted to Mesopotamia early the following year. He distinguished himself in the British advance guard, which captured Baghdad and skirmished north of the city, and was awarded the Military Cross. He was wounded again on March 29, 1917, declared “medically unfit for duty,” and evacuated to India.

But the tough Slim recovered and became a staff officer, impressing his superiors. Then, despite War Office objections, he transferred to the Indian Army with the rank of captain in February 1919. He joined the 1st Battalion of the 6th Gurkha Rifles in March 1920 and served as adjutant. On January 1, 1926, he married Aileen Robertson, the daughter of a Church of Scotland minister, who became his devoted “soldier’s wife who followed the drum.”

After studying at the Staff College in Quetta for two years, Slim served on the staff at Indian Army Headquarters in 1929-33. He also wrote pulp fiction, using the pen name Anthony Mills and explained that “the prime motive was cash.” He instructed at the Staff College in Camberley, Surrey, in 1934-36, attended the Imperial Defense College, and was gazetted a lieutenant colonel commanding the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Gurkha Regiment in May 1938. He soldiered with the Gurkhas on the North-West Frontier and integrated himself into the Indian Army. In 1939, after serving as commandant of the Senior Officers School at Belgaum, Slim was promoted to brigadier and posted to command the 10th Indian Brigade, part of the 5th Indian Division, at Jhansi in Uttar Pradesh.

In August 1940, after 11 months’ basic training, the brigade was ordered to the Sudan, where British and colonial units under Wavell and General William Platt were mustering to liberate Ethiopia and Eritrea from superior Italian forces. Slim’s brigade launched the first British offensive of the war late in 1940, but things went badly wrong because of inexperienced assault troops, obsolete tanks and planes, and poor planning and coordination, for which Slim blamed himself. The campaign could have ruined his career, yet he survived, and the Italians were eventually crushed in East Africa.

In mid-January 1941, meanwhile, Slim was wounded a third time—by a strafing Italian plane in Eritrea. Evacuated to India, he helped prepare contingency plans to prevent Iraq from defecting to the Axis Powers. When Iraqi pro-Nazi forces attacked the British base at Basra on May 2, 1941, an expeditionary force was dispatched, with Slim soon promoted to acting major general and leading the 10th Indian Division.

He gained valuable experience in his 10 months with the division. He learned how to move a division rapidly through mountainous country while launching successful assaults against a Vichy French garrison and other objectives in eastern Syria and occupying strategic areas of Iran before advancing Russian troops could reach them.

By the spring of 1942, the 10th Division was back in Iraq. Slim’s abilities had been noticed at high levels, and Wavell, now the British commander in India, proposed him as chief of staff, although he had wanted to stay in the Middle East. “The desert suits the British, and so does fighting in it,” said Slim. “You can see your man.”

Auchinleck, now the Middle East commander, opposed Wavell’s suggestion, saying that Slim lacked “the reputation, personality, and experience which would give the Indian Army full confidence.” But former Gurkha officers in embattled Burma urged their newly arrived chief, Alexander, to pressure Whitehall into appointing Slim as Burma Corps commander. Alexander complied, and on March 11, 1942, Slim—promoted to acting lieutenant general—flew into Magwe on the River Irrawaddy.

Within hours of his arrival, Slim talked to as many officers and men as he could and devised a plan for a Burcorps counterattack. His vigor and vision acted like a tonic on the corps, and the operation was launched. But the campaign was doomed from the start. The corps staggered from defeat to defeat as Slim received contradictory orders from Alexander’s headquarters and was denied clear directives. Time and again, Slim saw his careful plans for counterattacks rendered impotent. On March 30, he was ordered to launch an offensive down the Irrawaddy Valley to relieve pressure on Stilwell’s Chinese troops under attack at Toungoo in the Sittang Valley.

But Slim the realist knew that his corps was not up to the task. He predicted that the attack would end in failure, and it did. Still, as late as April 20, Slim planned a masterstroke offensive by his corps and a Chinese division down the Irrawaddy to halt the advancing Japanese. But the Chinese withdrew before the operation could be launched. Slim’s corps was forced to retreat, and on April 25 Alexander ordered it to pull back to India.

Ironically, Alexander was extolled by the BBC as “a bold and resourceful commander,” but the prickly “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell knew better. He said that because of his skillful handling of the two-month retreat “good old Slim” was the real hero.

By May 1942, a pattern had emerged which was to dog Bill Slim until the end of the Burma campaign. While his officers and men revered him, others who had not met him, including Churchill and Alexander, formed a low opinion of him. Credit was taken by others for his achievements, and blame was leveled at him for many of the Army’s setbacks. He angrily refuted criticism of his Burcorps troops.

After Slim’s convalescence and the disbandment of Burcorps, Wavell gave him command of the 15th Indian Corps, which was responsible for the seaward defenses of Calcutta. In September 1942, Wavell ordered his Eastern Army to advance into the Arakan region in west-central Burma and recapture Akyab from the Japanese. The offensive—the first of three attempts to secure the Arakan—proceeded smoothly until enemy resistance stiffened in January 1943.

Slim was sent in with his 15th Corps, but the British were repeatedly outmaneuvered, and the campaign degenerated into a grim struggle to rescue outflanked brigades and scattered battalions. Slim successfully extricated trapped units, transforming potential disaster into orderly defeat, yet he was unfairly blamed by Lt. Gen. Noel Irwin, the India-Burma border commander, and threatened with relief.

But it was Irwin who was sacked. Slim survived again, and his position improved when Irwin was replaced by the able, handsome General Sir George Giffard. The two men were similar in temperament and outlook.

Giffard became commander of the 11th Army Group, and Mountbatten took the helm of the new Southeast Asia Command. Lord Louis stressed offensive action and said that in the future fighting would continue during the monsoon season. Many veterans balked at the idea, but Slim did not. His support won him promotion to command of the newly formed British 14th Army in October 1943. It was a daunting challenge for the man who once remarked, “I must have been the most defeated general in our history.”

Comprising eventually 500,000 British, Indian, Gurkha, and East and West African troops, the 14th Army was deployed on a 700-mile front from the Chinese frontier to the Bay of Bengal. Along the Indo-Burmese border, it faced a wide belt of jungle-clad, precipitous hills—disease infested, unmapped in places, trackless during the monsoon rains, and, for half of the year, having the world’s worst climate. Morale and motivation were shaky in the 14th Army, and it ranked lowest on the Allied priority list for supplies and manpower.

But Bill Slim rose to the challenge and, aided by Mountbatten, spent several months building his new army’s battle strength and morale. With his motto, “God helps those who help themselves,” the general set up realistic training programs, with units sent into the jungle for weeks at a time. As Australian and American troops had learned respectively in New Guinea and the Pacific, Slim convinced his men that the Japanese were not supermen and could be defeated. He spent long hours talking informally with as many soldiers as he could, whether in English, Urdu, or Gurkhali, about their rations, mail service, and beer. Mentally robust and down to earth, Slim projected fighting spirit and good cheer. Responding with affection and admiration, the men started referring to him as “Uncle Bill.”

His philosophy was clear and direct. “The ultimate intention must be an offensive one,” he declared. “The main idea on which the plan was based must be simple. That idea must be held in view throughout, and everything must give way to it. The plan must have an element of surprise.”

Slim trained his army steadily and carefully. In initial limited attacks, he deployed brigades against single Japanese companies to ensure success and build confidence. Then patrols were dispatched ever farther into enemy-controlled areas. By late 1943, things were looking up, and the Allied troops in the Far East were feeling far better about themselves than they had six months earlier. Sickness rates had fallen because of Slim’s insistence on adequate medical supplies and rations.

His overall achievement was remarkable. He had taken charge of beaten, demoralized troops and, with virtually no support and scant resources from Britain, turned them into an army that on both the tactical and operational levels reached a standard that only the best of German units equaled.

The Allies were on the offensive that autumn. Three divisions of Slim’s former 15th Corps advanced into the Arakan, Stilwell’s Sino-American force pushed in the northeast to seize the city of Myitkyina and eventually link up with the strategic Burma Road, and long-range penetration raids by Wingate’s famed Chindit columns were continuing to wreak havoc behind the Japanese lines.

By the end of that year, the Japanese high command was aware that an Allied counteroffensive was in the works, so, in January 1944, orders were issued to General Renya Mutaguchi’s 15th Army for a preemptive attack against Kohima, Imphal, and Tiddim to destroy the 14th Army’s logistical bases and close the single all-weather road linking Burma with India. The enemy would thus secure their hold on Burma.

As a diversionary move, the enemy launched an offensive in the Arakan on February 4. This was brought to a halt in the furious “Battle of the Admin. Box,” where tall, audacious Maj. Gen. Frank W. Messervy’s British and Indian troops—supported by tanks and airborne supplies—fought desperately at close quarters to gain a defensive victory. The Japanese lost 5,335 men, and the British 3,506. The action was the first major British success in the Burma campaign.

Three of Mutaguchi’s divisions opened the main enemy offensive on March 8, with Slim defending a 300-mile front in the central sector. He had decided to make his main stand on the Imphal plain on ground of his own choosing. But his forces were stretched thin, with barely 3,000 men available at Imphal, so he called in the 5th and 4th Indian Divisions.

In the early hours of April 5, a regiment of Maj. Gen. Sato Kotoku’s Japanese 31st Division fell upon Kohima, the small Assam town 80 miles north of Imphal. Colonel Hugh Richards’s garrison fought hard to hold its shrinking perimeter until a British-Indian relief force could break through, but the situation became more desperate when the main enemy assault began. The fighting was ferocious, and the rival lines were drawn so close that the British and Japanese were dug in on opposite sides of the district commissioner’s tennis court.

But, in some of the war’s bitterest action, the worst Japanese attacks were repulsed on May 4-7. Elements of Lt. Gen. Sir Montague Stopford’s 33rd Corps arrived on May 11, and the tide turned against the enemy. Against orders and in a bid to save his division from “a meaningless annihilation,” Sato withdrew with 6,000 losses.

In and around Imphal, meanwhile, the main battle raged from April 5 as Lt. Gen. Sir Geoffrey Scoones’s 4th Corps doggedly resisted the uncoordinated but fanatical assaults of two Japanese divisions. Though cut off from land support, the defenders were aided by the unprecedented airdropping of 6,000 tons of supplies. The siege was raised on June 22 when advance units of the 2nd and 5th Indian Divisions linked up on the Imphal-Kohima Road.

Japanese cohesion snapped. Starving and having lost most of its transport and guns, Mutaguchi’s 15th Army pulled back to the River Chindwin in disorder. Five of his divisions had been virtually destroyed, with 53,000 men dead. The British-Indian toll was 17,000. Imphal was a disaster for the Japanese and a turning point for the Allies in the Burma war. Morale soared in the 14th Army, and Bill Slim, who had shown himself as a brilliant defensive general, received belated recognition. He was made a Knight Commander of the Bath on December 15, 1944.

Slim kept up the pressure on his enemy. The 14th Army had pursued the remnants of the Japanese 15th Army back across the Chindwin by September, and by December 3, three crossings had been forced. Slim planned a major offensive for early 1945, and the aim was nothing less than the destruction of all Japanese forces by thrusting into central Burma without delay and driving them southward. Although he had long been hampered by conflicting British and American objectives, Slim decided to give his foe no rest during the impending monsoon. With Mountbatten’s support, he overrode the misgivings of General Leese, new commander of the Southeast Asia Allied Land Forces, and campaigned on “in the wet.”

While Slim had a cool relationship with his eccentric and difficult subordinate, Wingate, and questioned the ultimate worth of his long-range raids, Slim was able to work closely and effectively with his American associates, such as Stilwell; Brig. Gen. Frank D. Merrill, whose legendary 5307th Composite Unit (the famed “Merrill’s Marauders”) distinguished itself at Myitkyina; and Colonel Philip G. Cochran, colorful commander of the 1st Air Commando Group, which gallantly supported 14th Army operations with supply drops.

Slim recognized Stilwell as “a tough, hard-bitten, plain fighting general,” but one who lacked strategic skills and “reached for the hammer to crack a walnut.” He regarded Merrill as a “fine, courageous leader who inspired confidence.”

The last major offensive of the Burma campaign was launched on Sunday, January 14, 1945. The Allied aim was to defeat the main Japanese forces in central Burma, protect the new Ledo Road link with China to the north, and facilitate the reconquest of the rest of Burma. Slim’s Anglo-Indian forces moved swiftly and with deadly purpose against three enemy armies commanded by General Hyotaro Kimura.

While the British 33rd Corps headed for Mandalay, concentrating Japanese attention there, the 4th Corps moved stealthily down the Kabaw and Gangaw Valleys, crossed the Irrawaddy on February 13, and seized the vital strategic-communications center of Meiktila on March 4. Enemy links with strategic Rangoon were cut. This was the masterstroke of the Burma campaign because it led directly to the disintegration of the northern Japanese front. Mandalay was captured on March 21 after a bitter struggle.

On April 1, Maj. Gen. Sir Francis W. Festing’s crack British 36th Infantry Division arrived from the north to back up Slim’s Anglo-Indians. The enemy fought tenaciously, but their counterattacks were too little and too late. Their defenses in central Burma were shattered, and the remnants of their divisions retreated in confusion along the Irrawaddy.

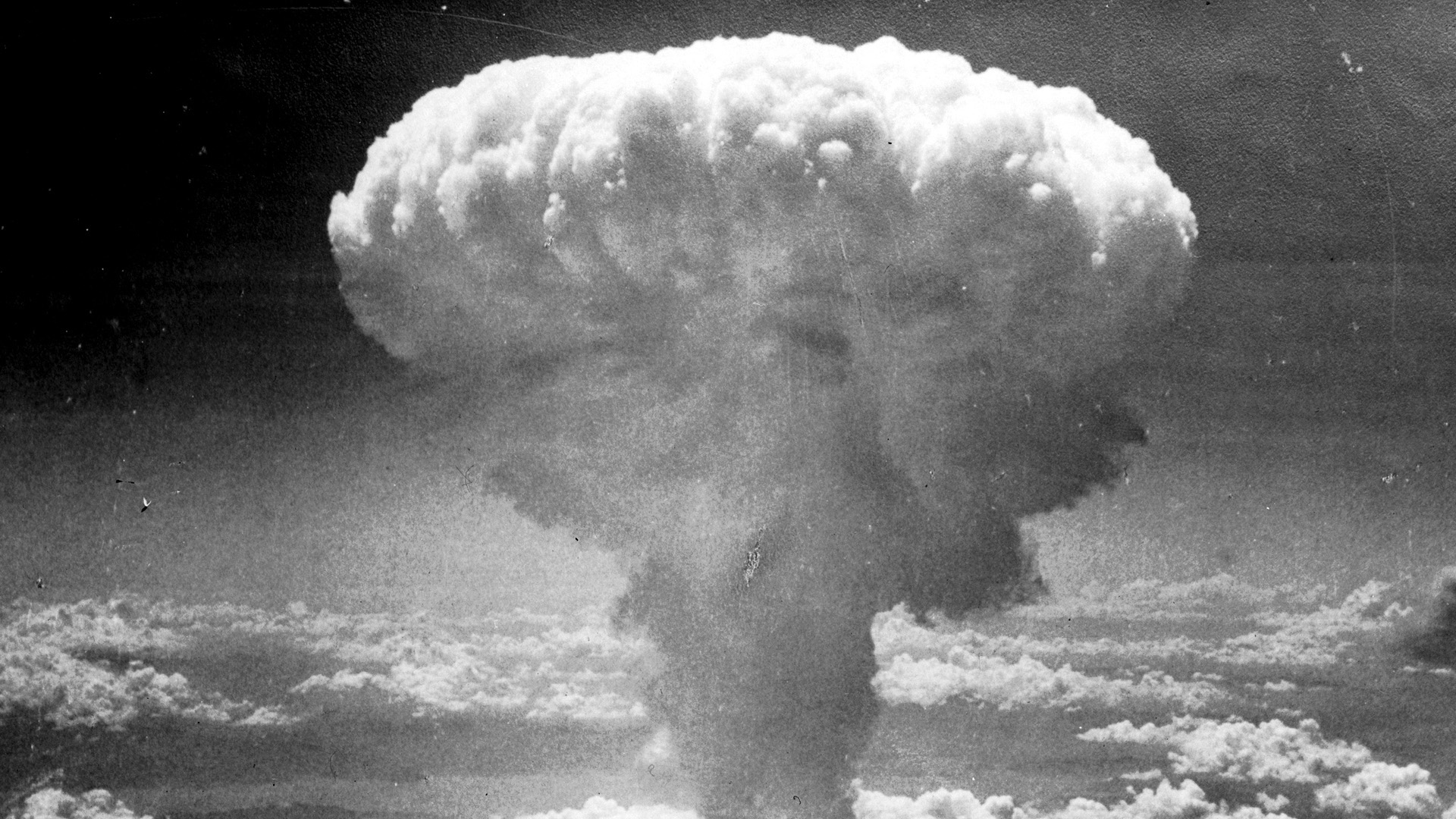

Supported by 15th Corps amphibious landings along the Arakan coast, Slim’s 33rd and 4th Corps made a lightning advance to reach Rangoon before an imminent monsoon hampered progress. The mission was accomplished on May 2, 1945, with the Japanese having lost a total of 350,000 men. This effectively concluded the Burma fighting. It was a decisive victory for Slim and arguably the most brilliant British ground campaign of World War II.

Slim was as proud of his men as they were devoted to him. “Armies do not win wars by means of a few bodies of super-soldiers, but by the average quality of their standard units,” he observed. “Any well-trained infantry battalion should be able to do what a commando can do; in the 14th Army they could and did.”

Anxious to convince the Japanese that they had been beaten in the field, Slim disregarded General Douglas MacArthur’s wishes and refused to allow surrendering officers to keep their swords. General Kimura’s sword eventually ended up on Slim’s mantelpiece, “where I always intended that one day it should be.”

Having already proved himself to be an inspired trainer and skilled defensive general, the Mandalay-Meiktila operation now placed the 14th Army’s Uncle Bill in the same league as Heinz Guderian, Erich von Manstein, George S. Patton, Jr., and Brian G. Horrocks as an outstanding offensive commander, as well.

On May 7, General Leese flew to Slim’s headquarters at Meiktila with the astounding news that he was to be relieved as 14th Army commander and take over the newly formed 12th Army for amphibious “mopping up” operations in Malaya. Slim refused, while a storm of protest swept through the 14th Army ranks at the treatment of their chief. Officers threatened to resign.

After Leese was dismissed, Slim succeeded him as commander of the Allied Land Forces in Southeast Asia on July 1. Promoted to full general that August, he commented wryly, “By good fortune in the game of military snakes and ladders, I found myself a general.” Slim returned to England after seven years’ absence, spent “a hectic but happy month” with his devoted wife, and met Prime Minister Churchill for the first time. The man who had once quipped, “I cannot believe that a man with a name like Slim can be much good,” was finally able to acknowledge his stature. “He has a hell of a face,” the prime minister observed.

Slim had become one of “Churchill’s generals,” but he did not succumb to his leader’s influence. After they had lunched in London in the summer of 1945, Churchill held forth expansively on his chances in the forthcoming general election, and Slim commented, “Well, prime minister, I know one thing. My army won’t be voting for you.” Churchill held no grudge, though he was ousted at the polls.

The Burma hero was active after the war. He headed the Imperial Defense College in 1946, was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire and served as deputy chairman of the nationalized British Railways in 1947. The following year, over the protests of his predecessor, he replaced Field Marshal Montgomery as Chief of the Imperial General Staff. Slim was promoted to field marshal in January 1949.

He was sworn in as governor-general of Australia in May 1953, and published his memoirs, Defeat into Victory, in 1956. It was a publishing sensation, and the first edition of 20,000 copies sold out in a few days. Accepted as the classic account of the 1942-45 Burma campaign, the book was hailed for its honesty and literacy. Brig. Gen. S.L.A. Marshall, the noted U.S. Army historian, wrote that “its sweep and elegance will spoil the subject for the historians who will try later.” Historian Mark M. Boatner III called it “one of the war’s finest memoirs,” while Time magazine said, “One of the war’s few great captains … a soldier who can reconstruct battles as brilliantly as he fought them.”

Slim was created a Knight of the Garter in 1959 and served in Australia until 1960, when he was elevated to the peerage as Viscount Slim of Burma. He then served as constable and governor of Windsor Castle in 1963, and died in London on December 14, 1970, at the age of 79.

Slim had secured a proud niche in the long history of the British Army, and tributes poured in on his passing. General Messervy recalled, “There was no brass hat about him,” while Major Gen. Sir John G. Smyth, who led the 19th and 17th Indian Divisions, believed, “He combined the best qualities of Monty and Alex.” Lord Mountbatten went even further and said that Slim was “the finest general the Second World War produced.”

The late Michael D. Hull was a frequent contributor to WWII History. He wrote for many years from his home in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments