By Robert F. Dorr & Thomas D. Jones

The captured German pilot was cocky and boastful. He had just parachuted into the American airfield, now lit up by the fires of burning Republic P-47 Thunderbolts, a sprinkling of bright torches amid the gray January gloom and the dirty white snow. It was January 1, 1945, and the Luftwaffe had just launched a surprise morning air attack on the base known as Y-34, a few miles from Metz, France, operated by the 365th Fighter Group, the “Hell Hawks.”

Like the Battle of the Bulge that raged all around them, the air attack was a stunning setback for American pilots, maintainers, and support troops operating the Thunderbolt on the continent of Europe. In the months since D-day, most had gotten accustomed to crude living conditions, lousy weather, and a war in which Thunderbolts harried the German Army at low level where a lot of metal was flying around. They were not, however, used to being attacked.

Friendly antiaircraft fire managed to shoot down eight of the 16 Messerschmitt Bf-109s that came over that day, but the Germans destroyed 22 Thunderbolts, badly damaged eight, and lightly damaged three more. The German pilot was now a prisoner of the Americans, but he obviously felt confident that his side had inflicted a major blow. Standing inside group headquarters with Major George R. Brooking, commander of the 365th Group’s 386th Fighter Squadron, the German jerked his thumb out the window and said in perfect English, “What do you think of that?”

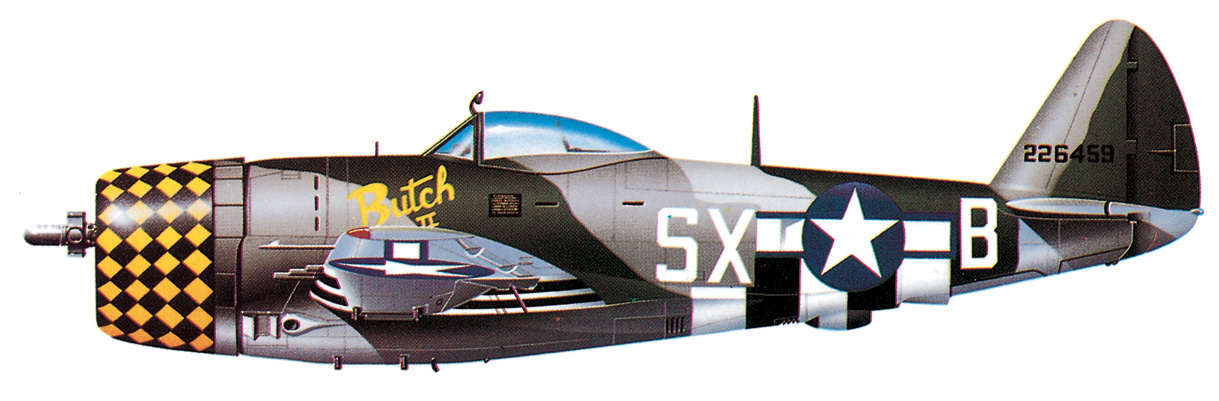

There was no denying the damage. But American industry had turned out nearly 100,000 warplanes in the calendar year that had just ended. Within a few days, Y-34 airfield was in full operation again and factory-fresh Thunderbolts lined the ramp. There was no mistaking the corpulent shape of the distinctive fighter planes—in jargon, American pilots referred to the P-47 Thunderbolt as the “Jug.”

Brooking went back to see the German, who was still being held at the base. Brooking pointed to the new planes and asked, “What do you think of that?”

It was time for a little humility. The German looked at the spanking-new aircraft, just arrived from a heartland that seemed capable of building an infinite number of them. He said, “That is what is beating us.”

Beating the Germans was exactly what Thunderbolt pilots in Europe were hoping to achieve during the nine months between June 1944 and May 1945. For these men at the controls of the powerful, heavily armed P-47, the war was no distant thing viewed from a Norden bombsight up near the edge of the stratosphere. Thunderbolt pilots of the Ninth Air Force fought their war up close and personal, eyeball-to-eyeball with German troops, vehicles, guns—and horses.

Tom Glenn, author of the memoir P-47 Pilots: The Fighter-Bomber Boys, said in an interview that one of his saddest duties was strafing columns of horse-drawn guns and equipment. “The horses were not our enemy,” said Glenn. “But our assignment was to prevent those columns from harming our troops.”

History has largely ignored the Ninth Air Force, in part because taking off from a snow-covered, muddy airstrip for low-level strafing and bombing is not as colorful as escorting bombers to Berlin, the job performed by Eighth Air Force fighters in England. Similarly, although it was the most numerous American fighter ever built, the Thunderbolt often takes a back seat when contrasted with the sleeker North American P-51 Mustang. Fifteen fighter groups, 45 squadrons, and about 14,000 Americans on the Continent fought the low-level P-47, a little noticed but powerful and lethal warplane.

With its 2,535-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-2800-59W Double Wasp 18-cylinder, twin-row air-cooled engine; 17,500-pound takeoff weight; and eight .50-caliber Browning M3 machine guns packing 250 rounds each, the Thunderbolt was the heavyweight fighter champion of World War II and the only aircraft that could carry out air-to-ground sorties where, as Glenn puts it, “a lot of metal was flying around.” It may have been the only fighter rugged enough to operate from hastily prepared airfields in France and Belgium, often with a runway length of 3,800 feet or less.

American industry built 15,683 Thunderbolts, a figure that compares with 15,486 P-51 Mustangs, 13,143 Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, and 12,275 Grumman F6F Hellcats. No fewer than 5,222 Thunderbolts were lost in combat. A further 1,723 were claimed by noncombat mishaps in the war zone.

So what was it like flying the P-47 on the Continent? Sometimes, it could be very personal, as it was for retired Colonel Milt Sanders, then a second lieutenant, who had a personal engagement with a German locomotive.

The Battle of the Bulge Grew into the Largest Land Battle in Which the U.S. Army Ever Participated, Involving no Fewer Than 600,000 American Troops

Sanders was a pilot in the 514th Fighter Squadron, 406th Fighter Group, flying from Ash, Belgium. On a mission against a German marshaling center, he dive-bombed the rail yard, strafed cars and locomotives in a classic gunnery pattern, and pulled out of an inferno of flame and smoke. “I was climbing when I saw a diesel-electric locomotive outside our pattern of destruction, trying to get away by charging for a tunnel entrance in a hillside,” the pilot remembered.

Sanders took the shortest route to attack and wound up on the deck in a head-on pass, strafing the locomotive. He saw hits on the locomotive and disabled it. Abruptly, he felt a tremendous shock and a jolt. He zoomed skyward, zigzagged out of flak, and settled into a course for home with five to 10 feet of his left wingtip missing. “I managed to nurse the crippled plane to base. My gun camera film showed that I’d rammed a pole while strafing the locomotive.”

The Germans launched their surprise attack in the Ardennes on December 16, 1944. German troops and tanks poured through American defenses, creating a “bulge” and a potential division of Allied forces. The resulting Battle of the Bulge grew into the largest land battle in which the U.S. Army ever participated, involving no fewer than 600,000 American troops. It also drew in Thunderbolts from every group that could reach the battle area.

In the pale winter sky on the morning of December 17, Major John Motzenbecker led a flight of four P-47s along the winding Prether River, searching for enemy activity among the snow-covered fields and dark green pine forests. Spotting a main road near the front, Motzenbecker called, “Give me some top cover; I’ll go down and have a look.”

What he saw on his low-level inspection left him gaping in disbelief. Clogging the road near Monschau, Germany, was a bumper-to-bumper column of Wehrmacht tanks, half-tracks, and troop trucks heading straight for the American lines. Motzenbecker counted more than 150 vehicles in a convoy stretching more than 41/2 miles. He had not seen such a tempting target since the German retreat out of the Falaise Pocket back in August.

He had lingered too long. Flak from the column below reached up, found him, and put a piece of shrapnel through his wing. Motzenbecker zoomed for altitude, reformed his flight, and called for the rest of the 387th Fighter Squadron to join the hunt. Checking in with the area controller, call sign Sweepstakes, Motzenbecker received confirmation that the threatening column was indeed in enemy territory. “That is the enemy!” was the call from Sweepstakes.

“Then send reinforcements,” radioed Motzenbecker. “We’re going down on them!”

In an account he gave in the History of the Hell Hawks, Charles Johnson’s out-of-print, unofficial history of the 365th Fighter Group, Motzenbecker described how his pilots rolled in on the enemy convoy. Taking turns by flight, the 16 Thunderbolts trapped about 50 trucks before they could pull off into the woods, catching them in a crossfire from their 128 .50-caliber machine guns. The simultaneous attacks caught the trucks broadside, the heavy slugs blasting many of them completely off the road and into the ditches, burning fiercely.

When the squadron had swept the road clean of German vehicles, Motzenbecker led his flight up and down the wooded side roads. What began as a chance encounter grew into a marathon air-ground battle that went on and on.

Spotting a platoon of tanks under the foliage, the Hell Hawks dive-bombed the panzers until they disappeared in a boiling cloud of smoke. The next pass revealed several tanks blown completely over, on fire and smoking. But the Germans fought back with a vengeance, streaking the sky with an intense barrage of 20mm flak. One of the 387th’s newer pilots, 2nd Lt. John D. McCarthy, was caught in the web of cannon shells. His aircraft exploded and crashed just yards from the road. The native of Canandaigua, NY, had been with the squadron barely a month.

By the time the daylong fight near Monschau was over, Major Motzenbecker’s squadron, joined by the rest of the Hell Hawks’ 365th Fighter Group, had played havoc with the German column. More than 115 German vehicles and artillery pieces were verified as destroyed, another 65 completely wrecked or damaged, and an unknown number of troops put out of action. The Thunderbolt pilots had lost two of their own to the storm of flak put up by the convoys.

The running battle had blunted the impact of that particular German column, but Hitler’s final counterattack moved forward elsewhere along the front. Unfortunately, bad weather the next day, December 18, kept most P-47s on the ground—but not all.

One of Motzenbecker’s colleagues got into the air on the 18th and battled low ceilings and a solid undercast that hid the German advance—almost. The pilot was Major George R. Brooking, who would soon taunt a German prisoner by pointing at factory-fresh Thunderbolts.

Brooking led a flight of his 386th Fighter Squadron Jugs down through the undercast near the front. Betting he would emerge from the fog and clouds before he slammed into the ridge tops of the Ardennes, Brooking broke out just a few dozen feet above the ground. Jammed together just a few feet apart on the valley road below was a long column of German armor. Brooking’s other element leader, Captain James G. Wells, Jr., threw his two 500-pound bombs into a cluster of eight tanks snaking along the road. When the smoke cleared, two of the tanks had vanished and the other six lay on their sides, guns twisted under them, down the slope from the road. The highway was now effectively blocked by two deep craters.

Over the course of the next month, the German assault put the Ninth Air Force fighter-bomber pilots to their most severe test, as they faced low ceilings, icing, and terrible visibility in addition to the grim determination of a desperate enemy. The weather was often a greater challenge than the foe; it helped that the American war machine was churning out new aircraft to replace those that went down in what one historian called the most severe European winter in the 20th century. When the skies cleared after Christmas, the aerial onslaught laid on by the P-47 groups destroyed any last hopes the German generals had for success in the Ardennes.

In January 1945, with the Germans retreating desperately from the Bulge, 1st Lt. Robert V. Brulle operated from K-29 airfield in Belgium and flew low-level sorties over the front lines. “You would have an Army guy in a Sherman tank talking to you on the radio,” Brulle remembered in a telephone interview. “When you appeared overhead, he would say something like, ‘We need you to bomb the Germantank hiding behind the little farmhouse with the red roof.’ The problem for us, overhead in our Thunderbolts, was that we could see dozens of farmhouses with red roofs. To pinpoint the enemy, we needed somebody directing our flying who spoke our language.”

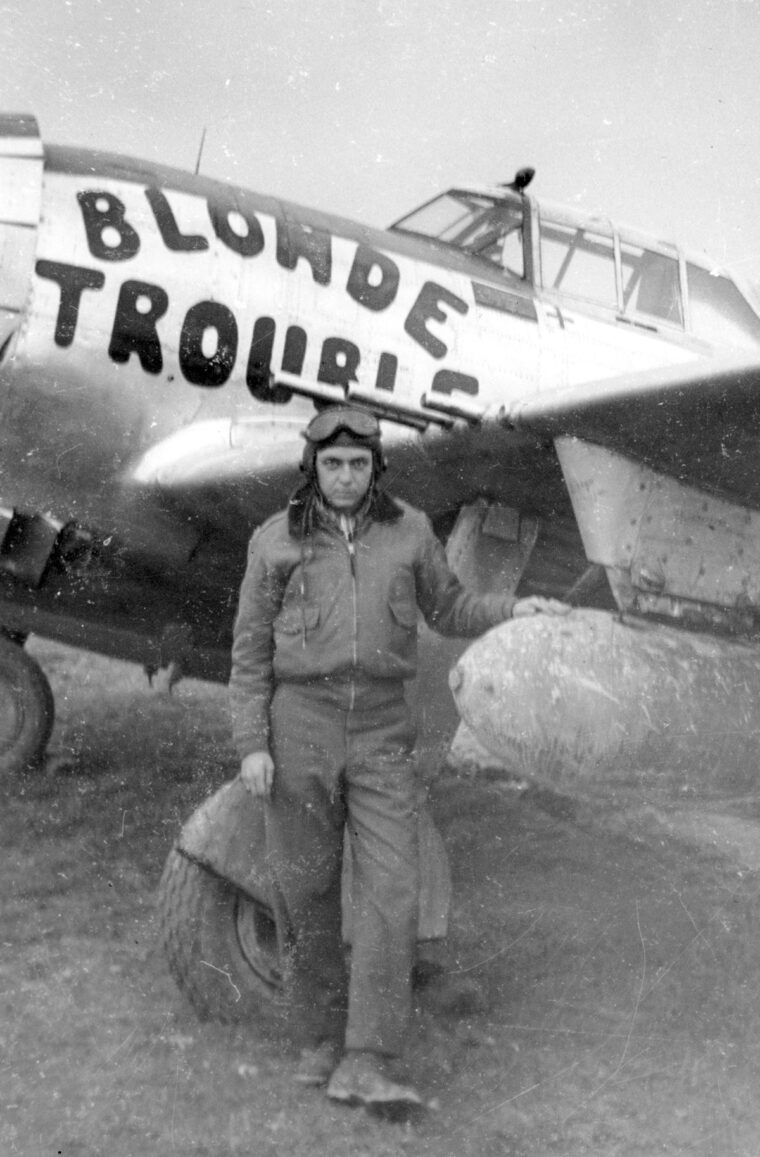

By the End of the War, Boze had Walked Away from Four Wrecked Fighter-Bombers, all Named, Appropriately Enough, “Blonde Trouble.”

So, fighter pilots like Brulle began rotating to the front, joining American ground troops and directing their fellow Thunderbolt flyers. “We would be talking to somebody we knew. We could say something like, ‘Turn right at the S-turn in the river, head up the two-lane road going 15 degrees northeast, and bomb the German tank behind the third farmhouse on the east side of the road.’” That, as it turned out, worked.

First Lieutenant Leslie Boze of the 365th Fighter Squadron, 358th Fighter Group thought he had seen everything in the P-47 since D-day. He had survived a gash in his skull from a canopy shattered by small arms fire over Brest. Near Saarbrucken, his P-47 had taken a direct hit from an 88mm flak projectile that shredded his left wing root, fuselage, and left flaps. By the end of the war, he had walked away from four wrecked fighter-bombers, all named, appropriately enough, “Blonde Trouble.” His faith in the massive Thunderbolt was unshakeable.

“This plane deserves greater recognition,” said Boze, who flew 107 combat missions and was credited with two aerial victories. He remembers an especially dramatic ground attack mission on that first full day of the Battle of the Bulge, December 17, 1944, near Neustadt, Germany.

Boze’s flight leader, a Captain Jones, was leading a strafing pass with 2nd Lt. Tom Easterling on his wing, followed by Boze and his wingman, a 2nd Lt. Gallaher. The four had already bombed the Wehrmacht road convoy when Jones, in the lead, opened fire with his eight .50-caliber machine guns as Easterling curved in behind him. A tremendous explosion rose from the burning column below. Tom Easterling was caught in the cloud of debris blown skyward. His plane staggered under the impact of what looked like “a piece of boiler plate” and immediately began smoking. Boze, trailing him, shouted over the radio, “Tom! The son-of-a-bitch is on fire! Get the hell out of it!” Easterling barely managed to jump from the burning fighter, opening his parachute just seconds before hitting the ground. With compound fractures in both legs, Easterling faced a long struggle against pain and captivity until liberated from a prisoner of war camp at war’s end.

Boze had scarcely begun his covering orbit of Easterling’s landing site when Gallaher yelled that they were being bounced by more than 20 Messerschmitts. Boze was forced to pull away from his downed comrade; he added power and climbed to meet the attack. Passing through 6,000 feet, he swung in behind a 109, and cutting him off through 270 degrees of a right-hand pursuit curve, pulled within shooting range.

Boze opened up and battered the right side of the enemy’s fuselage. The stricken 109 rolled over and dived straight down, on fire. Boze did not have the luxury of watching the impact because another Messerschmitt was already shooting at him. This 109, a head-on silhouette, was making good use of its hub-mounted 20mm cannon. A string of whitish golf balls streaked all too close to Boze’s cockpit. At extreme range, he recounts, he “lit my fifties a little early,” raising the nose a bit to loft the bullets toward the enemy.

As the Messerschmitt came within effective range, Boze could see his armor-piercing incendiary rounds hitting home, sparkling over the wings and cowling of the onrushing fighter. Still, the German pilot came on, nose-to-nose, in a deadly game of chicken. Boze held the trigger down as the two fighters came together. In the last split second, the German whipped over Boze’s Thunderbolt, a near-miss so close that through his canopy Boze heard the roar of the 109’s Daimler-Benz engine.

“He saw His Bullets Tear Bodies Apart; He Saw His Bombs Explode in the Middle of Gun Emplacements, Shredding Gun, Ammunition, and German Soldiers into Small Bits.”

More Messerschmitts were in the area, and again Boze was unable to visually track his victim to the ground. Short on fuel and ammunition, he finally headed for base, two oily fires burning on the ground below. After landing, he and his crew chief counted just 66 rounds left in his eight machine guns. The bullets expended gave Boze credit for one kill and one probable.

That kind of air-to-air action was what every World War II fighter pilot trained for and hoped for. But Boze and other Thunderbolt pilots on the Continent fought a dirtier, grittier war, as described by Glenn.

“The [P-47] fighter-bomber pilot was a killer,” Glenn explained. “He saw his bullets tear bodies apart; he saw his bombs explode in the middle of gun emplacements, shredding gun, ammunition, and German soldiers into small bits. He shot it out with antiaircraft guns, tanks, and armored cars at point-blank range. In most cases these encounters were not over until one or the other was dead.”

Americans were miffed when Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery announced the end of the Battle of the Bulge—an Allied victory—in a January 7, 1945, press conference. Americans felt they had done most of the fighting and that the announcement should have come from their leader, Supreme Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower. The battle ended with more than 40,000 German casualties, but it did not end the contribution made by P-47 Thunderbolt pilots. They fought on until VE-day.

Today, some P-47 Thunderbolt pilots refer to their fight on the European continent as “the war nobody told you about.” Their contribution to victory was monumental, but it rarely made the headlines or the history books. “Mostly,” said Glenn, “we fought because we had to. We did it for each other.”

Unspoken in Glenn’s words is the fact that he and his fellow pilots saved the lives of thousands of American GIs. Every enemy tank, every field gun, every troop convoy and ammunition train destroyed meant the U.S. Army soldiers at the front would face a battle-worn and ill-equipped Wehrmacht.

The GIs held a special affection for the Ninth Air Force planes that were nearly always overhead. When they looked up to cheer those pilots on, the fighter they glimpsed most often was the ubiquitous P-47 Thunderbolt.

Robert F. Dorr is an Air Force veteran, a retired U.S. diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel. Thomas D. Jones is a former Air Force B-52 pilot, a former NASA astronaut with four shuttle missions, and co-author of The Complete Idiot’s Guide to NASA, an introduction to space flight and the space agency. They live in northern Virginia with their families.

My Maternal grandfather Alexander Grieg Clark was an engineer at Bowater-Lloyds paper Imill near Sittingbourne in Kent. He made drop tanks out of Kraft paper and resin. I have a photo he left me in his will of Major John Motzenbecker next to a P47 Thunderbolt with a paper drop tank fitted and a bomb under the wing. I also have a 1/10 scale model of the paper drop tanks. He once told me that he had some part in developing the manufacture of the drop tanks. They had internal stiffening and had to be fueled (108 gallons) just before each flight.They became paper mache in contact with fuel after about 24 hours . When discarded over German held territory, they were useless, unlike steel drop tanks which had scrap value. The photo of Motzenbecker does not say where it was taken – my guess is Gosfield near Braintree in Essex but it could be in France after DDay. Motzenbecker led a flight on 17 Dec 1944 during the battle of the bulge, as described in the book “History of the Hell Hawks”, and in the Wikipedia entry above. Would love to get in touch with Motzenbecker’s descendants in the USA. I worked on the Hanger at Boeing Everett Field near Seattle -for the 787 i I was the geotechnical engineer doing drilling and testing to assist in design of the foundations for the massive building

My dad was one of the pilots who showed up at Metz on January 3rd. Fresh out of earning his wings and barely 20 years old, he landed near those ruined planes on the air strip, many still smoking. I hope he heard the rest of this story.

Everybody talks about the P51, and it was a great plane, but my favorite is the P47, because it was like the Energizer Bunny:

It just kept going, and going, and going.

Plus, my late Aunt made them here in my home town, at Republic Aviation – one of the original “Rosie The Riveters.”