By Peter Kross

Less than a year after the sudden and devastating Japanese attack against the United States at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the American military was about to embark on a large-scale offensive operation against German and Italian forces in North Africa.

Early Days of British and American Spy Agencies

Code-named Operation Torch, the American landings in the west and the advance of the British Eighth Army from the east would squeeze the Axis forces between them and eventually expel the enemy from North Africa. However, as military preparations for the landings took shape, a covert operation was under way directed against the leader of the pro-German armed forces in France, Admiral Jean Darlan. Just two months after the Torch landings, Admiral Darlan was killed in an operation linked to the super-secret British intelligence group MI-6, also known as the SIS (Secret Intelligence Service), and possibly the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the modern Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), led by William “Wild Bill” Donovan.

By 1942, after intense meetings between President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Prime Minister Winston Churchill of Great Britain, and to a lesser extent General Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French, it was agreed that the first large-scale offensive military campaign against the Germans would begin. This attack was planned against the German strongholds in French North Africa, with landings in French Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia to create a southern front for further landings in Europe and to relieve some of the pressure being felt by the Soviets on the Eastern Front.

Occupied France is Setback for Allies

These momentous events took shape following a major blow to the Allied cause, the fall of France to the Germans. When Hitler’s troops entered Paris, all effective resistance from the regular French Army ended. Hitler proceeded to divide the country into two distinctive sections, one controlled by French collaborators with its seat of government at Vichy. The other, which was mainly to the north, including the capital of Paris, was under German occupation.

Into this highly volatile mix strode the man at the center of events, Admiral Jean Darlan. Darlan was the French naval commander-in-chief under the pro-German Vichy regime and no friend of the Allies. As time went on, Darlan would serve as the de facto prime minister of the Vichy government and command all Vichy French forces in North Africa.

A Collaborator With a Storied Ancestry

Jean Darlan was born on August 7, 1881, in the French town of Nerac. His father served as a minister of justice in the French government. He traced his ancestry back to the Battle of Trafalgar, where one of his grandfathers was killed while commanding a ship in that momentous event. Young Jean graduated from the esteemed Lycée St. Louis in Paris in 1899, and later attended the French naval academy, earning his degree in 1902. During World War I, he commanded a battery of naval guns.

Darlan’s rise through the ranks of the French Navy was swift, and by 1929 he was promoted to rear admiral. His first major task was the rebuilding of the French Navy after the disarmament that followed the end of the “Great War.” Darlan personally supervised the reconstruction of the French fleet. By 1936, he was promoted to chief of the navy’s general staff and was responsible for all French maritime operations. He was now one of the most influential men in the French armed forces, and he used his power to the fullest extent.

Like many French military men in the pre-World War II years, Darlan was not enamored of anything British, including having to work with his counterparts in the British naval establishment. But as war clouds appeared on the horizon in the late 1930s, he was ordered to cooperate with the British, including the provision of French ships to support the Royal Navy in its operations in the Mediterranean. Many of the leading politicians and military men in the French government hoped that Admiral Darlan’s hatred for the Germans was greater than his dislike for the British.

Admiral Darlan Wastes No Time in Grabbing Power

If nothing else, Darlan was an opportunist of the first order, and he showed his true colors shortly after the fall of France in June 1940. With France now in his grasp, the Führer appointed Marshal Philippe Pétain as the head of the Vichy government. Pétain was a mere figurehead, doing the bidding of his German masters. Darlan was given wide powers within the Pétain administration, the most important being control of the large French fleet which was still virtually untouched by the war. Later, decisive action by the British Royal Navy crippled elements of the French fleet and assured the Allies that these ships would not fall into German hands.

When the Allies invaded North Africa in 1942, an enraged Hitler canceled the peace accord he had arranged with Vichy in 1940 and took measures to occupy all of France.

Darlan believed that the Germans would inevitably win the war and did all he could to keep the Vichy regime in Hitler’s good graces. By 1941, Darlan had assumed two new posts: minister of the interior and minister of defense. It was Vichy policy to support the Germans as much as possible, going so far as to offer them the use of the former French colonies with their strategic locations and vital raw materials.

Darlan Works Both Sides to His Advantage (and His Peril)

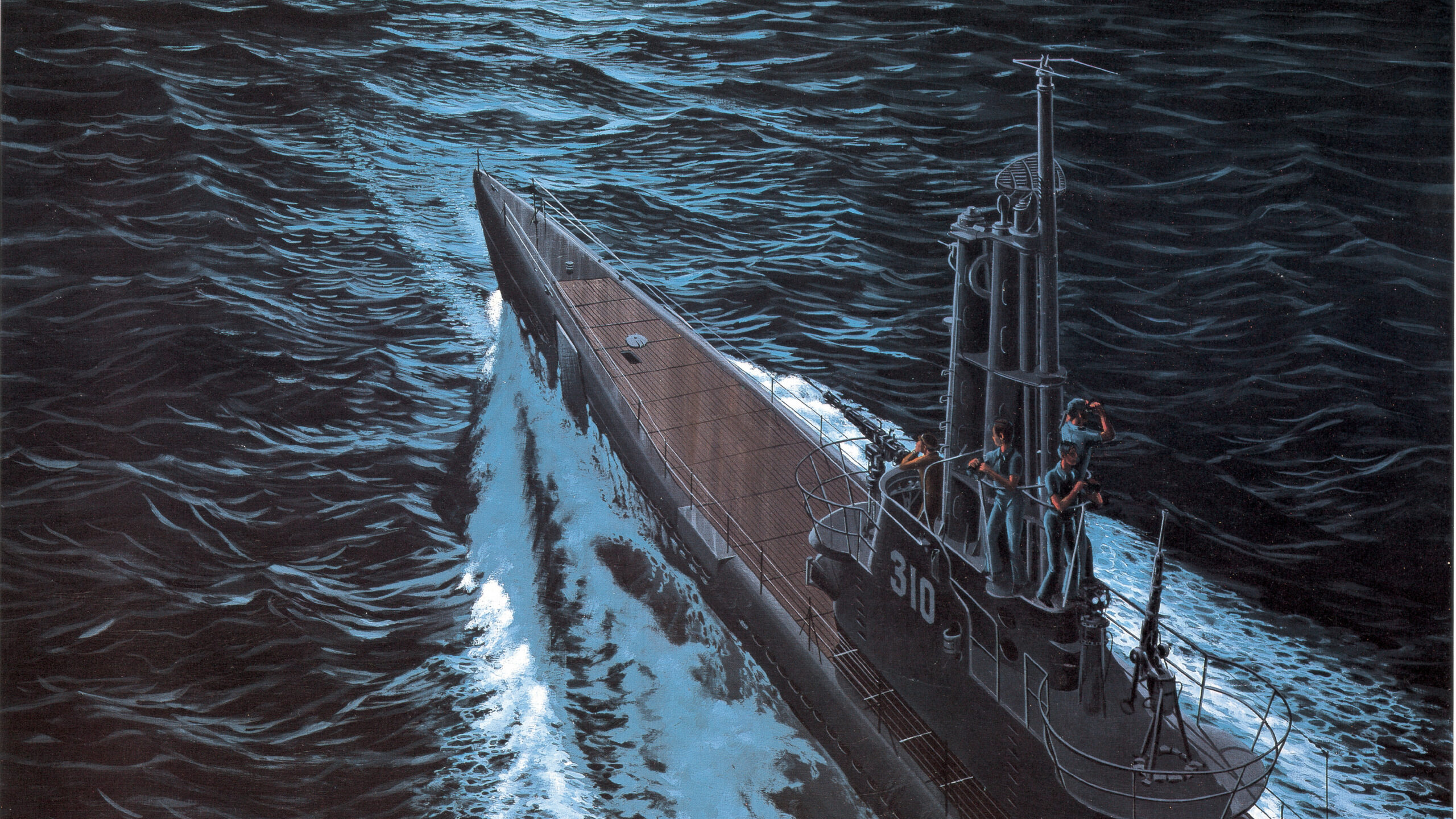

In the United States, the Roosevelt administration received information from the OSS about covert Vichy operations in Central and South America. It was reported that Vichy agents were infiltrating the Caribbean island of Martinique, then prowling around the region while the port was being used as a refueling base for German U-boats.

For all of Darlan’s German sympathies, he drew the line in advance of full cooperation and made contact with the United States in the months leading up to Operation Torch. All of his intrigues came at the same time that he was designated as Pétain’s successor on February 10, 1941.

Darlan was now playing both ends against the middle in his dealings with the Allies and the Germans. During a visit to French Algeria in October 1941, he ordered his subordinates in the Navy to counter any Allied attack on Dakar, Senegal. At the same time, the admiral made contact with the Americans, telling them he was prepared to cooperate when the Torch landings took place.

U.S. diplomat Robert Murphy contacted Darlan in early 1942 and also began discussions with the admiral’s son, Alain, an officer in the French Navy. Murphy’s initial meeting with young Darlan and another officer came in April 1942. In his reports back to Washington, Murphy said that the two Frenchmen welcomed working with the United States in the upcoming invasion of North Africa and would come to the Allies’ side at the appropriate moment. Murphy cabled home, “I was greatly encouraged by their apparent eagerness, sincerity and desire for Franco-American collaboration.”

Ike Wisely Decides Not to Trust the French

Unfortunately, Alain Darlan was suddenly stricken with polio while stationed in Algiers. Over a short period of time, the admiral would make numerous trips to his son’s bedside while using these travels to meet with Murphy and Maj. Gen. Mark Clark, who served as a deputy to General Dwight D. Eisenhower during the important Torch period.

Murphy avoided revealing details concerning the size of Operation Torch and the locations of the landings. However, he told General Eisenhower that to gain the confidence of the French military all information regarding Torch should be shared with them. Eisenhower dismissed the idea, telling Murphy that within days of the French getting wind of the information, it would be delivered to the Germans. Ike ordered Murphy to deceive the French naval officers, telling them that the projected invasion date was February 1943.

America Infuriates de Gaulle by Acknowledging Darlan

To complicate matters further, it was decided in Washington not to inform General de Gaulle’s Free French forces of the date and time of the Torch invasion. President Roosevelt distrusted and disliked de Gaulle because of the latter’s criticism of the United States’ diplomatic recognition of the Vichy regime. It was decided in Washington and London to stick with the lesser of two evils, Admiral Darlan. In hindsight, it probably was the wrong move to make.

The Darlan affair showed just how fragile the relationship between the Americans and the Free French really was. De Gaulle, it turned out, was to become the dominant political figure in France following the country’s liberation. From London, de Gaulle badgered the United States for more supplies for his resistance movement and started a running feud between the United States and British secret services as to who would provide the most supplies. De Gaulle was furious with General Eisenhower and the United States when Ike decided to recognize, with Washington’s approval, Darlan’s role as the political and military leader of France.

In retaliation for the American recognition of Darlan, de Gaulle stopped all cooperation between the OSS and his own intelligence service. The fallout of the Darlan affair caused the British and the pro-Allied French to rally around de Gaulle, leaving the United States, at least temporarily, out in the cold.

Captured, Then Quickly Set Free

As Allied troops came ashore in North Africa, Darlan took political center stage. Having been tipped off by his secret service agents in Algiers that the invasion was imminent, he waited in that centuries-old city for developments to unfold. As it turned out, he did not have long to wait.

Darlan was given a 24-hour notice that the invasion was about to begin, and as he made his way to contact Vichy regarding the news, he was arrested, along with General Alphonse Juin, the commander of the land and air forces in French North Africa. They were taken into custody by a dashing military officer by the name of Henri d’Astier, who was in charge of a prominent French underground resistance movement called the Chantiers de la Jeunesse (the “Young Workmen”). Besides taking the two men prisoner, d’Astier’s forces took control of the Algiers radio station and the police stations.

D’Astier initiated these measures a bit too hastily, just hours before the actual invasion began. He had no backup from the invading Allied forces, and his fighters were driven off by the French Army loyal to Vichy. Soon both Darlan and Juin were released.

Americans Make a Difficult Offer to Refuse

As soon as he was freed, Darlan began hurried conversations with Allied leaders, telling the Americans that the only person he would speak to was General Eisenhower himself. Eisenhower rebuffed Darlan, sending Maj. Gen. Clark in his place. The meeting between Darlan and Clark was to have long-lasting political and military ramifications that would affect all sides of the conflict.

Clark came right to the point with Darlan. He said that both President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill were willing to deal with him as the chief political and military spokesman of the French government, but only on their explicit terms. Their terms were an immediate cease-fire by French forces in Tunisia and a pledge by the admiral not to interfere with the Allied landings. If Darlan agreed, the Allies were willing to temporarily forget his not-so-secret affiliations with Vichy and the Germans and give Darlan control over the civilian population in French North Africa. He was also given the title High Commissioner in French North Africa.

Unexpected and Sudden Demise of the French Navy

Immediately upon his acceptance of the Allied terms, Darlan issued a cease-fire order to all Vichy troops in North Africa. He also instructed the French fleet in the port city of Toulon to depart and link up with the Allied fleet. Unfortunately, Darlan’s orders regarding the Toulon fleet were not carried out. Instead, Admiral Jean Laborde, the commander in the Toulon area, ordered that the fleet be scuttled to prevent its falling into the hands of the Germans. In all, one battleship, two cruisers, four heavy and three light cruisers, 24 destroyers, and 10 submarines were purposely sunk.

The so-called “Darlan Deal” put an end to the fighting between the Allies and the French forces, ensuring a successful landing on the North African coast. While the military news was good, an international firestorm of protest concerning the agreement with Darlan reared its ugly head.

Back in The States, a Political Firestorm Erupts

Protests began pouring forth from political leaders on both sides of the Atlantic. Their basic question was this: Why were the Allies dealing with a collaborationist, a man who had openly given aid to the Germans?

One of the first people to speak out against the Darlan deal was Donovan of the OSS. In a letter to his “customers,” probably the president, Secretary of State Cordell Hull, or the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Donovan wrote, “The identification of Darlan with our operations in North Africa presents difficulties which cannot be ignored. These difficulties are not changed, whether Darlan foisted himself upon us or was forced upon us by someone else, or whether we made a deal with him on our own.… By whatever means we were placed in this position, we have before us the very practical problem of eliminating the political leadership of Darlan with its attendant consequences to the French people and in our own successful prosecution of the war. Our great influence with the people of France has been due not only to our strength but to our straight dealing. It is apparent that the continuance of the present situation will weaken our traditional position. We cannot wait too long to find a solution.”

Churchill’s and FDR’s Secret Correspondence

The distrust of Darlan shared by Roosevelt and Churchill is evident in their correspondence, which was first published in Churchill’s wartime memoir The Hinge of Fate(1950). From the beginning of the war, both leaders carried on a highly personal and secretive correspondence known only to one another.

In a letter dated November 17, 1942, from “the Former Naval Person” (Churchill) to Roosevelt, the British leader spells out his concerns regarding Darlan’s rise to power: “I ought to let you know that very deep currents of feeling are stirred up by the arrangements with Darlan. The more I reflect upon it the more convinced I become that it can only be a temporary expedient, justifiable solely by the stress of battle. We must not overlook the serious political injury which may be done to our cause, not only in France but throughout Europe, by the feeling that we are ready to make terms with the local Quislings (Darlan). Darlan had an odious record. It is he who has inculcated in the French Navy its malignant disposition by promoting his creatures to command. It is but yesterday that French sailors were sent to their death against your line of battle off Casablanca, and now, for the sake of power and office, Darlan plays the turncoat.”

On November 18, 1942, Roosevelt answered Churchill’s letter regarding his thoughts about Darlan. “I too have encountered the deep currents of feeling about Darlan. I felt I should act fast, so I have just given out a statement at my press conference which I hope will be accepted at face value. I have accepted General Eisenhower’s political arrangements made for the time being in Northern and Western Africa. I thoroughly understand and approve the feeling in the United States and Great Britain and among the other United Nations that in view of the history of the past two years no permanent arrangement should be made with Admiral Darlan. People in the United Nations likewise would never understand the recognition of a reconstitution of the Vichy Government in France or in any French territory. We are opposed to Frenchmen who support Hitler and the Axis.”

Darlan Attempts To Spin His Actions To Allies

For his part, Admiral Darlan knew that his deal with the Allies was temporary in nature and took it in stride. The arrangement with the Allies had allowed the Western powers to successfully prosecute the war in French North Africa. Darlan’s feelings about working with the Allies are revealed in a letter he penned to Maj. Gen. Clark. “Monsieur le General, Information from various sources tends to substantiate the view that I am only a lemon which Americans will drop after they have squeezed it dry. I acted only because the American Government has solemnly undertaken to restore the integrity of French sovereignty as it existed in 1939, and because the armistice between the Axis and France was broken by the total occupation of Metropolitan France, against which the Marshal [Pétain] has solemnly protested. I did not act through pride, ambition, or calculation, but because the position which I occupied in my country made it my duty to act.

“When the integrity of France’s sovereignty is an accomplished fact—and I hope it will be in the least possible time—it is my firm intention to return to private life and to end my days, in the course of which I have ardently served my country, in retirement.”

As events played out, Darlan’s desire for a peaceful retirement would be only wishful thinking.

A Man Hated and Distrusted From All Quarters

By December 1942, it was obvious to any interested party that Admiral Darlan was a marked man. He had made so many enemies of all stripes that one would need a scorecard to keep track. The Allies distrusted him because of his earlier pact with the Germans. The Germans called him a traitor for giving the orders to scuttle the French fleet, as well as making the deal with Eisenhower. De Gaulle’s Free French forces also considered him a traitor and yearned to replace him at all costs.

The Darlan problem was top priority among the men of the British Secret Service headquartered in London. With the Germans in control of the Vichy Zone in France, resistance groups fighting an underground war against the German occupiers did so at much greater peril.

Darlan’s Fate Decided Over Lunch

Sir Alexander Cadogan, head of the Foreign Office, succinctly made his feelings known concerning Darlan after the Toulon fleet episode when he said, “The Americans and naval officers in Algiers are letting us in for a pot of trouble. We shall do no good until we’ve killed Darlan.” Cadogan further discussed what to do about Darlan in a December 8, 1942, meeting at the Savoy Hotel with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, General de Gaulle, and a General Catroux. During the conference, when the topic of Darlan’s fate came up, de Gaulle remarked, “Get rid of Darlan. My answer is ‘Yes’; but how?”

What the men at the Savoy luncheon did not know was that while they were discussing the “Darlan problem,” plans for his execution were already under way.

Among the prisoners released in the amnesty following Darlan’s takeover was a Frenchman named Bonnier de la Chapelle. Chapelle supported the Comte de Paris, whom he believed should be the true occupant of the French throne. During the war, Chapelle joined the underground movement headed by Henri d’Astier, the Chantiers de la Jeunesse. This group was connected to the Free French and aided the Allies when they landed at H-hour. Bonnier de la Chapelle now joined another paramilitary organization called the Corps d’Afrique, which served as a “special unit intended to utilize all elements in French North Africa—politically active French subjects, non-French refugees, natives, and Jews under restrictions.”

An Elite Corps of Special Operatives in North Africa

The Corps d’Afrique’s training base was located at Ain-Taya, near Cape Matifou, not far from Algiers. What made this location special was that it was run by a British espionage organization called the SOE (Special Operations Executive). The SOE’s job during the war was to “set Europe ablaze” with underground attacks across the Nazi-occupied continent. The head of British Intelligence, Sir Stewart Menzies, managed all clandestine operations, including the Corps d’Afrique. The SOE gave these fighters training in special warfare techniques including small arms, subversion, and sabotage. Bonnier de la Chapelle was one of its trainees.

If this hotbed of intrigue was not enough, another party now entered the mixture. Shortly after the Corps was formed, Donovan sent Carleton Coon, one of his most trusted OSS agents, to observe training. Coon was to serve as the OSS representative and report back any information he deemed necessary. As a young man, Coon traveled to North Africa, the Balkans, the ancient lands of Ethiopia, and the Middle East doing anthropological work. He also taught at Harvard and joined the OSS when the war broke out. In an unusual move, the British dropped all association with the Corps, leaving Coon and the OSS in charge.

A Priest, a Youth, and a Soldier Hatch a Plot

What Coon did not know (or at least as he later said), a plot to kill Darlan was hatched among certain members of the Corps d’Afrique at the Ain-Taya base of operations. The conspirators were Roger Rosfelder, Henri d’Astier, and a soldier named Mario Faivre. It was Faivre who devised a plan to kill Darlan—using a British-made Sten gun—from a car caravan along a route Darlan usually took. Later, Rosfelder said it was only talk and that another man—a priest named Abbé Cordier of the Church of St. Augustine who had clandestine associations with d’Astier—had secretly met with the assassin, Bonnier de la Chapelle. According to Rosfelder, the priest so impressed Chapelle with his anti-Darlan talk that the young man decided to make the hit.

The meeting between Abbé Cordier and Chapelle took place on December 23, 1942, one day before Darlan was assassinated. Coon later told Donovan that it was at that meeting that the priest gave Chapelle a choice of murder weapons.

On Christmas Eve, 1942, Robert Murphy met with Darlan at the admiral’s room at the Hotel Palais d’Eté. While the meeting was going on, Rosfelder, Faivre, and another man drove Chapelle to Darlan’s hotel.

Fatal Shot Rings Out in Hotel Palais d’Eté

Unchallenged, Chapelle entered the hotel and shot Darlan, firing his Colt Woodsman pistol at point-blank range. Interestingly, Chapelle’s pistol had been originally owned by Carleton Coon. Chapelle was immediately arrested and taken into custody. Darlan’s wounds were mortal, and he died later that afternoon.

Within two days of his being captured, Chapelle was tried in a secret court and summarily executed. Severe, quick, end of case.

However, the death of Admiral Darlan did not end the affair. In the aftermath of the assassination, accusations and questions would begin to swirl around the possible involvement of both the OSS and the SOE in Darlan’s demise.

Benefits and Repercussions of an Unholy Arrangement

The news of Darlan’s assassination traveled like wildfire across the capitals of the Allied powers. In both Washington and London there must have been silent thanksgiving that the problem of the traitorous admiral had been taken care of. Back in Algiers, where the killing had taken place, covert events were moving fast. In the wake of the assassination, General Henri Giraud was named commander-in-chief of French forces in North Africa. Writing in his memoirs, Churchill commented on Darlan’s death. “Darlan’s murder, however criminal, relieved the Allies of their embarrassment at working with him, and at the same time left them with all the advantages he had been able to bestow during the vital hours of the Allied landings.”

Carleton Coon had been in the city when Darlan was shot, and he quickly made his way out of sight. One of the first people Coon talked to following the assassination was William Eddy, a personal friend of William Donovan, and one of the most respected men inside the OSS. Eddy was chief of the OSS station in Algiers, and was responsible for sending agents into French North Africa. As OSS station chief, Eddy knew all the behind-the-scenes machinations regarding Allied interest in getting rid of Darlan.

Darlan Assassination Provides Inspiration for Covert Killings

Eddy told Coon that in the wake of the admiral’s death, reports of OSS involvement in the deed were sure to come out. He pointed out that opponents of the OSS would tie Chapelle to the OSS-run Corps d’Afrique and, more importantly, tie Coon to Eddy as his teacher. As far as Eddy was concerned, Coon had a more sinister side to his nature. Coon was an advocate of political assassinations in wartime. He wrote, “Therefore, some other power, some third class of individuals aside from the leaders and the scholars must exist, and this third class must have the task of thwarting mistakes, diagnosing areas of potential world disequilibrium, and nipping the causes of potential disturbances in the bud. There must be a body of men whose task is to throw out the rotten apples as soon as the first spots of decay appear.”

In order to forestall a police investigation into any possible OSS connections, Eddy ordered Coon to leave Algiers. Coon wound up in an SOE outfit where he donned a British captain’s uniform. He also gave himself a new cover name, “Captain Ritinitis.”

Rumors Fly and Conspiracy Theories Grow

Another unexplained twist to Darlan’s murder involved the presence in the city at the time of the assassination of the head of British Intelligence, “C,” Sir Stewart Menzies. Immediately after the admiral’s death, rumors emanating from members of the French military implicated the British in the murder. It was reported that the British were also planning to assassinate other leaders, such as General Eisenhower and Robert Murphy.

Most puzzling to conspiracy theorists is why Menzies, the head of the British Secret Service, would leave his safe HQ in London and just happen to be only miles from the scene of the assassination, calmly having lunch with his pals. When Menzies and his party were informed about the assassination, they showed little surprise.

Adding to the mystery surrounding Menzies’ appearance in the vicinity of Darlan’s murder are comments made by his personal assistant at the time, Patrick Reilly. Reilly wrote that in December 1942, shortly before the assassination, Menzies asked him if he would like to take a short, unexpected leave of absence. Reilly took the vacation, and when he returned Menzies was in his office as usual. Later, Reilly would write that he had no idea that during his absence “C” had been away. Was Reilly’s absence a perfect cover for Menzies to go to Algiers to oversee the fallout from the assassination?

De Gaulle Assumes Leadership and Exonerates Assassin

But the circumstances of the assassination had more unexpected twists. One year after Chapelle killed Darlan, a large number of French officials under the direction of de Gaulle and Giraud observed a minute of silence in honor of the assassin. One week later, also on de Gaulle’s orders, an Algerian court nullified the sentence against Chapelle, saying, “Documents [were] found which showed conclusively that Admiral Darlan had been acting against the interests of France and that Bonnier’s act had been accomplished in the interests of the liberation of France.”

Whether or not there was a grand conspiracy in the murder of Admiral Jean Darlan, his removal from power was a blessing for the Americans, the British, and the Free French. De Gaulle was now the leader of the resistance, and the Allies had complete control over military and political affairs in North Africa. Allied troops now paved the way for the D-day invasion of France, two years in the future. Darlan, in death, did more for the Allied cause than anything he could have done in life.

Has Admiral Darlan not been assassinated, I wonder if he would have been tried as a collaborator (and possibly executed) like Pierre Laval was in October 1945?

Certainly, Darlan’s elimination was fortuitous for General de Gaulle and Allied affairs.

Interestingly, the admiral’s remains lie buried in Algiers, capital of Algeria, which gained independence from the French in July 1962 just under 20 years after his assassination instead of being repatriated for reburial in Metropolitan France.

I had the mistaken idea that Admiral Darlan was assassinated using a Colt .32 automatic, the Model 1903. Donald Hamilton’s fictional Matt Helm in “Death of a Citizen” carried a short-barrel Colt Woodsman .22 pistol in World War Two–the same model and caliber used to assassinate Darlan?