By Pat McTaggart

As Adolf Hitler began to formulate his grandiose plans for the conquest of the Soviet Union, he considered the far northern operation area little more than a sideshow. Neither he nor his general staff realized the importance of the harsh, unforgiving tundra that contained a rail line connecting the port of Murmansk to the rest of Russia. It would prove to be a considerable miscalculation.

Ice-Free Northern Port

Located about 150 miles above the Arctic Circle, Murmansk was the only northern Soviet port that was ice-free year round. Thanks to the Gulf Stream, Kola Bay, the gateway to Murmansk, could handle shipping when the larger northern port of Archangel was frozen solid.

During World War I, Czar Nicholas II had a rail line built between Murmansk and St. Petersburg (Leningrad). About 70,000 German and Austrian prisoners of war labored for two years to construct the 850-mile track. When it was completed in 1917, more than 25,000 graves marked the route—the final resting places of prisoners struck down by typhoid during the brief, searing days of summer, and by malnutrition and the cold during the bitter eight-month Arctic winter. When the United States entered the war in 1917, the Murmansk rail line became a strategic supply route for American goods to reach the Russian heartland.

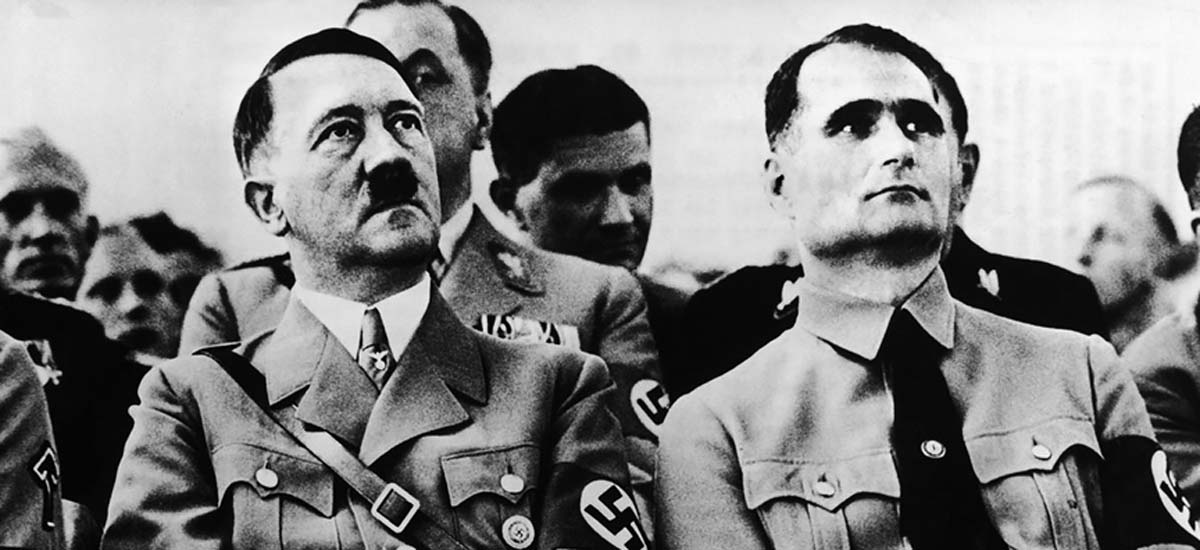

“Hero Of Narvik”

None of this mattered to Hitler in April 1941 as he met with General der Gebirgstruppe (General of Mountain Troops) Eduard Dietl to discuss the mission of Dietl’s Gebirgskorps “Norwegen.” The Führer was concerned about the safety of the nickel mines in Finland at Petsamo (now Pechenga) and with the vulnerability of the ore-rich area around Narvik, Norway, once the Reich and the Soviet Union were at war. To Hitler, the Murmansk rail line was only a means for Stalin to quickly move troops to the northern regions for an offensive against these vital areas.

The 50-year-old Dietl and some trusted staff members had been working on the planned Arctic attack for more than three months. Known as the “Hero of Narvik” for his daring seizure of the port during the 1940 invasion of Norway, the Bavarian general had already served Germany for more than 30 years. Joining the Army in 1909, Dietl saw some of the fiercest fighting of World War I, including several battles along the Somme, in Flanders, and at Arras. He had earned both classes of the Iron Cross and had the Wound Badge in silver before the war ended.

Unforgiving Terrain

Remaining in the Reichswehr (the 100,000-man postwar German Army), Dietl rose through the ranks and was given command of the 3rd Gebirgs (Mountain) Division in 1937. In 1940 his division helped overrun Norway, and by June of that year he had been given command of the newly formed Gebirgskorps Norwegen. Now, as he waited to meet the Führer, Dietl was prepared to brief Hitler about the tremendous obstacles that lay ahead for his men.

Soviet maps showed few roads in the desolate tundra, which was covered with snow and ice during the long winter. In the summer, the land became a gigantic swamp that was crisscrossed with untamed rivers, streams, and lakes. Some areas were also covered by dense forest. Moving men, supplies, and pack animals through such terrain would require superhuman effort.

As Hitler strode into the room, the general stood at attention. With a brief gesture toward a map table, the leader of Germany began to give his own assessment of the situation in the Murmansk sector. He pointed out that the airfields in and around the city of 100,000 posed a serious threat to German forces in the Far North, and that Luftwaffe aerial reconnaissance photos showed that Murmansk had a huge rail yard that could receive thousands of troops daily.

“We Must Eliminate This Danger At the Very Beginning”

Hitler also worried about the vulnerability of the ore-rich regions that could be lost if the Russians managed to launch an offensive strike in the area. “It could be disastrous,” he said. “We must eliminate this danger at the very beginning of our Eastern campaign. Not by waiting, but by attacking. You’ve got to manage those ridiculous 60 miles from Petsamo to Murmansk with your Gebirgsjäger, and thus put an end to the threat.”

Somewhat taken aback by the phrase “ridiculous 60 miles,” Dietl began to detail the logistical problems that his divisions would face. He hoped to dissuade Hitler about directly attacking Murmansk, arguing that the severing of the port’s rail line would serve the same purpose and would have more chance of success. “If the rail line is interdicted,” he said, “the port and its defenses will eventually wither on the vine.”

A Typical Hitler Compromise

Hitler listened patiently, asking questions and studying the map that lay before him. When the general finished, Hitler told him to leave his plans for him to study, which Deitl took as a good sign. By the first week of May, Hitler had made his decision. The operational plan that he sent to GeneralOberst (Col. Gen.) Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, commander of Armee Norwegen and overall commander of the far northern sector, was a typical Hitler compromise.

Code-named Silberfuchs (Silver Fox), the final plan called for a three-pronged attack against Murmansk and its vital railway link. Dietl’s Gebirgskorps Norwegen was given a threefold mission—one defensive and two offensive. The defensive mission was to guard the Norwegian sector north of Narvik against a possible Soviet invasion. For this purpose, he had the 199th Infanterie Division (made up of older soldiers who were fit mostly for garrison duty); a police battalion and three machine-gun battalions; the 9th SS Infanterie Brigade; and a hodgepodge of naval and coastal artillery units.

A Two-Thrust Plan

The first of his offensive missions involved seizing the area around Petsamo and advancing to Polyarny and Port Vladimir, closing the Kola Bay north of Murmansk. His second objective was the city of Murmansk itself. For these tasks, Dietl had the 2nd and 3rd Gebirgs Divisions, a Bau (construction) battalion, a communications battalion, two batteries of 105mm guns, a Nebelwerfer (rocket launcher) battalion, and a reduced-strength antiaircraft gun battalion.

A second thrust would be made in the Salla area, about 190 miles south of Petsamo, by General der Infanterie Hans Feige’s XXXVI Armeekorps (redesignated a Gebirgskorps in October 1941). Feige’s Korps consisted of the 169th Infanterie Division, SS Division “Nord,” and the 6th Finnish Infantry Division. It also included two battalions each of tanks and motorized artillery, a heavy-weapons battalion, communication and bridge construction battalions, two antiaircraft and two Nebelwerfer battalions, and two Bau battalions.

Feige’s task was to smash the Soviet positions at Salla and then advance to the rail line north of the White Sea. When he reached the railroad town of Kandalaksha, he would then turn north to participate in the attack on Murmansk. Part of his force would also set up blocking positions along the rail line to prevent Soviet reinforcements from strengthening the Murmansk defenses.

Air Support Sorely Lacking

About 90 miles south of Salla, Maj. Gen. Hjalmar Siilasvuo’s III Finnish Corps (Group J and Group F—the equivalent of two brigades) was charged with taking the railhead at Kesten’ga. After Kesten’ga was secured, the Finns would then seize the towns of Loukhi and Kem, severing the Murmansk rail line in two more areas to make it even more difficult for any Soviet relief effort.

Unlike other areas at the beginning of the Russian campaign, the German forces of the Northern Theater could not count on much support from the Luftwaffe. GeneralOberst Hans-Jürgen Stumpff’s Luftflotte 5 was the poor relation of Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring’s air force. With little more than 250 aircraft to accomplish his primary mission of defending the skies over Norway, Stumpff could provide little in the way of air support for ground operations. For Silberfuchs, Luftflotte 5 could only contribute three long-range reconnaissance aircraft, a group of 30 bombers, and another squadron of 10 fighters. There were also seven short-range reconnaissance aircraft attached to Armeekorps Norwegen.

Finns Not All In

Hitler’s plans were based on Finnish cooperation, but the Finns were also considered the wild card of Silberfuchs because the Helsinki government was not yet fully committed to joining the German attack. As the date for the invasion, June 22, grew closer, German-Finnish negotiations were ongoing. Finland demanded and received assurances that all Finnish troops would be under the command of Field Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim, commander of the Finnish Army. This resulted in a dual-command system, which meant that there would be two independent commanders, von Falkenhorst and Mannerheim, in the same theater of operations—a certain recipe for confusion on the battlefield.

Operations in the far north were set to commence one week after the June 22 invasion. This gave von Falkenhorst more time to get his troops to their jump-off points, and it also gave the Germans a few more days to continue to negotiate with the Finns. As German artillery began blasting Soviet forward positions in the early hours of the 22nd, talks between Berlin and Helsinki were still in progress.

Operation Barbarossa Commences

When Operation Barbarossa began, Finnish Premier Johann Rangell let the world know that his country would maintain a strict neutrality for as long as possible. The neutrality statement also warned that Finland would not hesitate to defend itself in case of an unprovoked attack, a phrase clearly directed against the Soviet Union.

The Soviets received the Finnish declaration with great skepticism. They knew that there were already German forces on Finnish soil, and Luftwaffe high-level reconnaissance flights had been observed flying over Russian air space for some time. They also knew that Dietl’s Gebirgskorps was poised on the Norwegian-Finnish border near the Norwegian town of Kirkenes.

In the chaotic first day of Barbarossa, the Soviets struck back wherever they could, and the Red Air Force hit several Finnish border communities before night had fallen. Three days later, on June 25, larger formations appeared over southern Finland, laying waste to several towns and causing many casualties.

Finland And Russia Unofficially At War

The Finns claimed that their Air Force shot down 26 Russian aircraft during the raids of the 25th. Although neither side had made a formal declaration, the two countries were, for all practical purposes, at war. The air raids, coupled with Soviet artillery attacks on more border communities, resulted in a secret meeting of the Finnish Parliament. Putting the facts and casualty figures before the legislators, Rangell received a unanimous declaration to use whatever means necessary to defend the country. On June 28th, reconnaissance units were sent across the Soviet border to identify Red Army positions and supply routes. The following day, Silberfuchs began.

The Murmansk attack plan called for the assaults to be staggered, with Dietl’s two divisions jumping off on June 29, followed by attacks from Feige’s and Siilasvuo’s corps on July 1. Dietl’s assault force numbered about 27,500 men. Besides the two 105mm batteries attached to the Gebirgskorps, each division was supported by its own regimental artillery consisting of 75mm mountain guns and 100mm mountain howitzers. Moments after the assault began, the Gebirgsjäger cheered as Luftwaffe bombers and fighters flew overhead on their way to blast the airfields at Murmansk.

Soviet Planes Decimated & A Bold Command Decision

Although few in number, the German aircraft wreaked havoc on the Red Air Force. The air crews were amazed to see Soviet fighters sitting unprotected at their airfields, lined up as if on parade. Most of the hundred or so Soviet fighters stationed at the airfields were destroyed by the bombing and strafing and, as the German planes made their return trip to the west, vast clouds of smoke were already rising from the battered Russian facilities.

Although the Red Air Force was caught unprepared, even though Russia and Germany had been at war for a week, it was a different matter on the ground. On June 21, the day before Barbarossa began, General V.A. Frolov, commander of the 14th Army, asked for permission to deploy some of his units into their forward positions. The request was denied by the Defense Commissariat, but the Soviet general took it upon himself to order the deployment. It was a daring decision, since the Red Army was still reeling from the Stalinist purges that had decimated its ranks. A more cautious commander would never have taken such a risk in the face of a denial from higher authorities.

Recognizing the importance of the Murmansk area and its vital rail link to the rest of the Soviet Union, Frolov ordered his 52nd Rifle Division to take up defensive positions guarding the port. His 42nd Rifle Corps, based at Kandalaksha on the White Sea, was also alerted to be ready to move at a moment’s notice. These precautions, coupled with the fact that Silberfuchs was scheduled to begin a week after Barbarossa, would make it even more difficult for the German-Finnish forces to complete their mission.

Roads On Map Simply Did Not Exist

On June 29, Dietl’s Gebirgskorps attacked with Generalmajor Ernst Schlemmer’s 2nd Gebirgs Division advancing on the left, while Generalmajor Hans Kreysing’s 3rd Gebirgs advanced on the right. Schlemmer’s first concern was the Rybachiy Peninsula, which stuck out into the Barents Sea. Due to the lack of reconnaissance, Schlemmer knew little about the Soviet defenses that may or may not have been guarding the neck of the peninsula. The men of the division came mostly from the Tyrolean Alps area of Austria, and the forbidding tundra that lay before them did little to remind them of their homeland.

Schlemmer’s 136th Gebirgs Regiment advanced through a heavy fog. As it neared the Rybachiy Peninsula, there was no sign of enemy activity. By the end of the 29th, a screening force was left to cover the neck of the peninsula while a stronger force headed to Titovko to capture a strategic bridge in the town. It was hard going, especially when the Germans found that the roads shown on their maps simply did not exist.

German Offensive Launched

On the right flank, the 137th Gebirgs Regiment had a more difficult time. Advancing through the fog, the Germans ran into a strong Soviet defensive line consisting of pillboxes and fortified strongpoints. The troops manning the positions were Siberians and Mongolians who refused to surrender even after being wounded or surrounded, and the Gebirgsjäger soon learned that the war with the Soviets would not be a walkover. Because of the fog, air and artillery support were useless; however, the fog also made it possible for the main regimental force to infiltrate past the enemy positions, which would subsequently be destroyed by air attacks and direct fire from antiaircraft guns.

Meanwhile, Kreysing’s division had made good progress, advancing to the Titovko River and beyond. Once across the river, the division was supposed to advance southeast about 19 miles to the Litsa River and the town of Motovka. When the Gebirgsjäger began their march on the town, they too discovered that their maps were useless. What they had assumed were road markings were actually Soviet indications of telegraph lines, and they soon realized that there was not even a track or crude trail leading from the Titovka to the Litsa.

Reality Forces Dietl To Regroup

When Dietl learned that there was no way that Kreysing’s division could advance through the swamps and tangled brush that lay between the two rivers, he ordered it to pull back across the Titovka and head northeast to assemble behind the 2nd Gebirgs Division. The combination of piecemeal reconnaissance, bad maps, and even worse terrain had forced the German commander to revise his planning even before the first day of Silberfuchs had ended.

On June 30, the attack resumed. Schlemmer’s 136th Gebirgs Regiment was forced to use two of its battalions to hold the neck of the Rybachiy Peninsula, which had been found to contain at least one Soviet infantry regiment and some artillery. The Russians had also landed reinforcements in the Kutovaya area. Titovka was taken by the 136th’s remaining battalion, while the 137th finally found a track that allowed it to push forward to the Litsa River.

The following day, units of both divisions reached the Litsa after marching through some of the worst terrain they had ever seen. Most units only managed to move about one kilometer per hour. Upon reaching the river, Dietl’s men found that they faced two Russian rifle divisions (14th and 52nd) that already had a couple of regiments digging in to defend the river line. Frolov’s bold move of June 21 was about to pay off.

Germans Encounter Highly Motivated Foe

In total, the 14th Army had about six divisions in the area from Murmansk to Kem. They were not, as the Germans had originally assumed, second-rate or mediocre troops. Motivated by political commissars, they were prepared to fight to the death, showing courage, skill, and determination in battle and using every available defensive position to defeat the invaders.

Dietl now faced the challenge of establishing a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Litsa quickly, so that the Russian defenses could not be consolidated. The Rybatchiy Peninsula was finally sealed off on July 4, but with the influx of Soviet reinforcements into the area it took two full battalions to hold the line instead of one, forcing Dietl to further change his operational plan. The Red Air Force was also showing itself over the Litsa while the Luftwaffe was stretched to the limit, having to also support the attacks of Feige and Siilasvuo in the south.

On July 3, Gebirgsjäger of the 137th crossed the Litsa just above the river’s estuary. Fanning out on the eastern shore, they moved forward until they ran into scattered Soviet defensive positions. With no follow-up troops to support them, they were forced to halt their advance and establish a perimeter to protect the small bridgehead. Meanwhile, Schlemmer and Kreysing struggled to get the bulk of their divisions forward for a major attack across the river. With few roads to use, the draft animals used to haul the mountain artillery guns found the going particularly hard. Ammunition and other supplies were also lacking at the front because of the terrain.

Hitler’s “Norwegian Phobia” Costs Dietl Another Battalion

The attack on the Litsa line began on July 6, even though the 3rd Gebirgs Division had only a few units in position. It was delayed by several hours because of Soviet artillery strikes in the assembly areas, but by the end of the day three battalions were across the river, establishing a bridgehead about two miles wide. During the attack, the Red Navy landed troops on both shores of Litsa Bay, forcing the 2nd Gebirgs Division to detach another battalion to screen its left flank.

Dietl’s Gebirgskorps was further depleted when, on July 7, he received an order to strengthen defenses around Petsamo because Hitler feared a British amphibious landing in the area. Hitler continuously tied down several divisions in Norway during the war because of his “Norwegian phobia.” Because of the order, Dietl lost another battalion plus three much-needed artillery batteries.

Little Relief Is Forthcoming

Faced with the landings on Litsa Bay and Hitler’s order to strengthen the Petsamo area, Dietl had no choice but to pull his men back to the west bank of the Litsa after heavy Soviet attacks on the bridgehead. He angrily sent a message to von Falkenhorst demanding more air support, and said that ground reinforcements were also needed before the attack on Murmansk could continue. Although von Falkenhorst was unable to promise air support, he did manage to convince Mannerheim to send the understrength 14th Finnish Infantry Regiment to the Petsamo sector. The German commander also sent a motorized machine-gun battalion from Armee Norwegen to help alleviate Dietl’s manpower problems.

It took a week before Dietl felt strong enough to renew his attack on the Litsa line. The problems caused by terrain in the region were still hampering the movement of supplies to the front, and the pack animals used for transport were falling dead from sheer exhaustion. Deploying troops in the main areas of attack was also difficult because of the lack of roads and trails leading to the river jump-off points.

Soviet General’s Foresight Frustrates German Advance

Meanwhile, the attack of General der Infanterie Feige’s XXXVI Armeekorps was also in trouble. Feige had intended to use a double envelopment to capture Salla and then push forward to Kandalaksha, cutting the Murmansk rail line. His 169th Infanterie Division (Generalmajor Kurt Dittmar) and the SS Division “Nord” (Brigadeführer Karl Demelhuber) were poised near the Finnish border just west of Salla, while Colonel Verner Viikla’s 6th Finnish Division was positioned about 45 miles south of Salla, ready to advance to the northeast and cut deep into the Soviet rear.

Feige planned to use the 169th as a battering ram to smash the Soviet defenses in front of Salla, while Nord would cross the border and envelop the town from the rear. Once again, however, Frolov’s disregard of orders upset the German plans. The 42nd Rifle Corps had already arrived in the Salla area, and its two divisions (104th and 122nd Rifle) were dug in behind strongly fortified positions. The corps was also supported by about 50 tanks, as well as by numerous artillery batteries that were cleverly concealed in the thick forest.

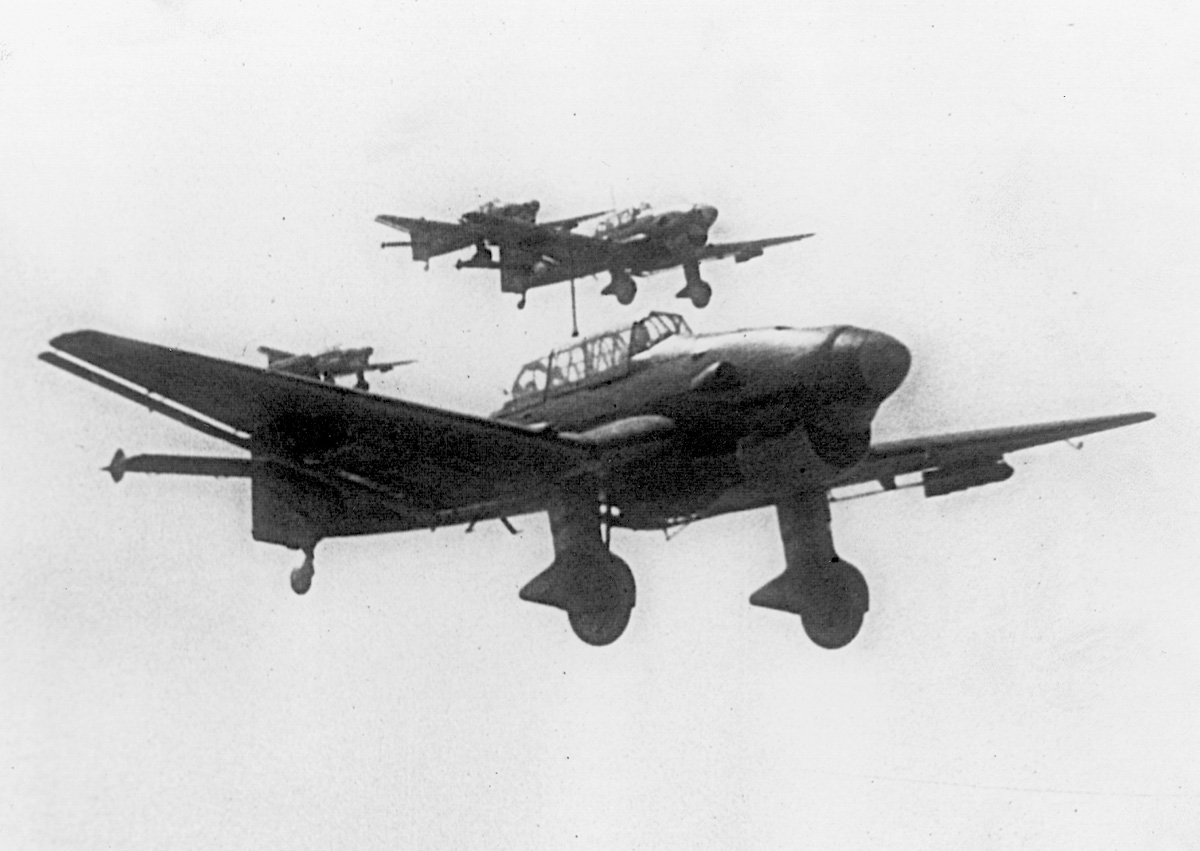

“White Nights” Provide Small German Advantage

Thanks to the 24 hours of summer daylight, the Germans did not begin their attack until 4 pm on July 1. This gave the attacking forces the added advantage of having the sun at their backs. Supported by Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers and artillery, the German forces crossed the border and headed for Salla, less than four miles away. The temperature was in the high 80s, and the swamps and stagnant pools of water swarmed with mosquitoes. Smoke from the bombardment obscured vision, and in several areas the forest had been set on fire by bombs and artillery.

About 500 yards inside the Soviet border, Dittmar’s right flank was stopped cold by strong Soviet positions. Although his center and left flank were able to advance a couple of miles against fierce Soviet opposition, plans for a quick capture of Salla had already been upset.

Nord Division’s Inexperience Proves Costly

Things were worse for the Nord Division. Most of its officers had very little military training, and the divisional artillery had fired its guns only once since the unit had been organized. The division had shown such poor march discipline on its trek from Norway to Finland that its previous commander, Brigadeführer Richard Herrmann, had been relieved. Coupled with the difficulties that the other seasoned German divisions faced, it is little wonder that Nord’s first combat experience proved to be a disaster.

Nord’s frontal attack against the heavily fortified Soviet positions was thrown back with heavy losses. Artillery coordination was almost nonexistent, and by the middle of the second day of battle Demelhuber reported to Feige that his men were unable to carry out further operations. The stunned Korps commander then ordered Demelhuber to take his division back to its border defensive positions in Finland.

On July 4, the division was sent into a panic when sentries thought they heard Russian tank engines in the distance. The roads were soon clogged with men and vehicles as the SS men streamed deeper into Finland. Roadblocks were set up to stop the retreat, and the fleeing troops were eventually diverted to new assembly areas, but the division was rendered virtually useless for the next few days.

Salla Falls, But Harsh Conditions Continue To Frustrate Germans

To make up for the loss of the SS division, Feige asked for a regiment of Generalleutnant Erwin Englebrecht’s 163rd Infanterie Division, which had recently moved through Sweden to support Finnish operations. On July 6, the attack on Salla continued with assault troops of the 169th crossing the Kola River and Viikla’s Finns striking from the south. Supported by Stukas and artillery, the attack made good progress against stiff Soviet resistance.

Salla was taken on July 8 as the Russians fell back to new positions to the east. The pursuing Germans and Finns soon ran into another strong defensive belt near the village of Kairala, about 10 miles east of Salla. There they were stopped cold.

Once again, the inhospitable terrain had served the Russians well. Although the forward German assault companies could keep up with the enemy retreat, the cumbersome supply and artillery units could not. As Soviet reinforcements streamed toward the Kairala position, the lead German units were forced to wait impotently while a new road was painstakingly cut through the forest for their support units.

Thirteen Miles In One Month

It was not until July 28 that Feige ordered the attack to continue. By that time, the Soviet positions had been further strengthened with men and materiel. The assault was hopelessly bogged down by the following day and was called off on the 30th. Feige’s corps had advanced about 13 miles in one month and had suffered around 5,500 casualties. It was becoming increasingly clear to the German commanders in the Northern Theater that without more men and equipment the taking of Murmansk was doomed.

Dietl’s attack on the Litsa had fared little better. Although the 2nd Gebirgs Division had pushed seven battalions across the river on July 13, Schlemmer’s men had only gained about two miles. On the 14th, the Germans ran into a strong enemy defensive line, which stalled the attack. Frolov also sent reinforcements by sea to land along the Litsa and Motovskiy Bays. Two days later, the Russians launched a series of counterattacks against the German bridgehead. Soviet forces on the Rybatchiy Peninsula, strengthened by reinforcements, also launched attacks on the battalions covering that sector.

Additional Support Too Little, Too Late

By July 18, Dietl was forced to reduce the Litsa bridgehead to meet new Soviet attacks in the Litsa Bay area. Although most of the 3rd Gebirgs Division had come into the line, his corps was still stretched to the limit, holding a 36-mile front. The situation worsened during the next few days as the Soviets continued to pressure the Germans. Red Air Force bombers came over the front daily, blasting Dietl’s positions, and the Russian ground attacks continued to whittle away the strength of the German front-line units.

Dietl was doing all he could to hold the lengthy front, and he told von Falkenhorst that, if reinforcements were not sent, the Murmansk operation was finished. Von Falkenhorst, impeded by Hitler’s order to keep Norway strongly garrisoned, managed to scrape together four battalions, which arrived at the front at the end of July.

On August 2, bolstered by the fresh reinforcements, an attack to eliminate the Soviet forces in the Litsa Bay area was initiated. After some heavy fighting, the Germans wiped out one Russian battalion and forced a second one to be evacuated by sea, eliminating the Soviet threat to the Gebirgskorps’ left flank. The Korps was still not strong enough to continue the attack across the Litsa River, but after some pleading with Berlin, Armee Norwegen managed to get the 388th Infanterie Regiment and the 9th SS Infanterie Regiment released from Norway. Hitler also promised the 6th Gebirgs Division, which was currently stationed in Greece.

Finns Make Progress Using “Motti” Tactic

Winter was only about 10 weeks away, and it would take almost a month for the regiments stationed in Norway to redeploy to the front. The troops from Greece would take longer. Russian forces on the Litsa River had gone into a defensive posture after the August 2 attack on the Litsa Bay sector, and the front would remain stagnant until September, when Dietl planned to renew the offensive against Murmansk.

The only real success in July came from Siilasvuo’s III Finnish Corps. Siilasvuo had made good progress after crossing the border. Against relatively weak resistance from the Soviet 54th Rifle Division, Group J had taken the town of Makarley, 17 miles inside Russian territory, by July 5, while Group F had advanced 28 miles, capturing the village of Pon’ga Guba.

Siilasvuo continued his advance—his troops using the so-called “motti” tactic of breaking through the enemy flanks and rear in rapid thrusts, encircling relatively small groups of Russians, and destroying them before moving on. It was a tactic that had served the Finns well during the 1939-1940 war with the Soviet Union, and it worked better in the heavy forests than the sweeping encirclements that were practiced by the Germans. By July 18, the Finns had advanced almost 40 miles.

German Offensive Gets New Life (Thanks To Finns)

Armee Norwegen was so impressed by the Finns’ progress that it sent the Nord’s 6th SS Infanterie Regiment and the division’s Artillerie Regiment to reinforce Group J’s attack. Their movement to the front was facilitated by a road the Finns had built during their advance.

Meanwhile, the Finns continued their drive toward the rail spur at Kesten’ga. During the remaining days of July, Siilasvuo’s men overcame stiff Soviet resistance and advanced to within about 12 miles of Ukhta, where Group J ran into another powerful defensive network that was anchored on the Sof’yanga River. It took the Finns three days of heavy fighting to breach the Soviet defenses, but by August 3 they were on the march again.

Kesten’ga was taken on August 7, followed by an advance along the rail spur line that allowed the Finns and their SS reinforcements to come within 20 miles of Loukhi. Although the 54th Rifle Division had suffered heavy casualties, it was being reinforced by the 88th Rifle Division, which had been on the move for the past few days. With Loukhi almost within his grasp, Siilasvuo was forced to call a halt in the face of stiffening Soviet resistance. On August 23, he informed von Falkenhorst that his exhausted men could go no farther without reinforcements.

German-Finnish Pincers Have Red Army In Retreat

Feige’s attack in the Salla area was also stalled by the end of August. Reinforced by Nord’s Infanterie Regiment 7 and the Aufklärungs (reconnaissance) Batallion Nord, XXXVI Armeekorps had taken more than two weeks to redeploy for a new attack. On August 19, the 169th Infanterie and the SS regiment opened their assault on the Soviet positions about 15 miles northeast of Salla, while the 6th Finnish Division and the SS reconnaissance battalion Nord struck the Russians from the south.

Overcoming heavy Soviet resistance from the 104th and 122nd Rifle Divisions, German and Finnish combat groups drove deep into the enemy’s rear, hoping to encircle the two units. By August 22, the Soviets were in headlong retreat, abandoning equipment and vehicles in a mad dash to escape. The German-Finnish pincers were supposed to meet at Nurmi Lake, some 10 miles behind the Russian frontal positions, but the terrain prevented this from happening until the 27th, which gave many of the fleeing Soviets the opportunity to escape.

Still in hot pursuit, the Germans and Finns were brought to a halt at the Vayta River. The pre-1940 Russian fortifications along the river now held the remnants of the two divisions that had escaped encirclement, as well as a fresh motorized regiment from the 1st Tank Division. Once again, the attempt to cut the Murmansk rail line had been thwarted.

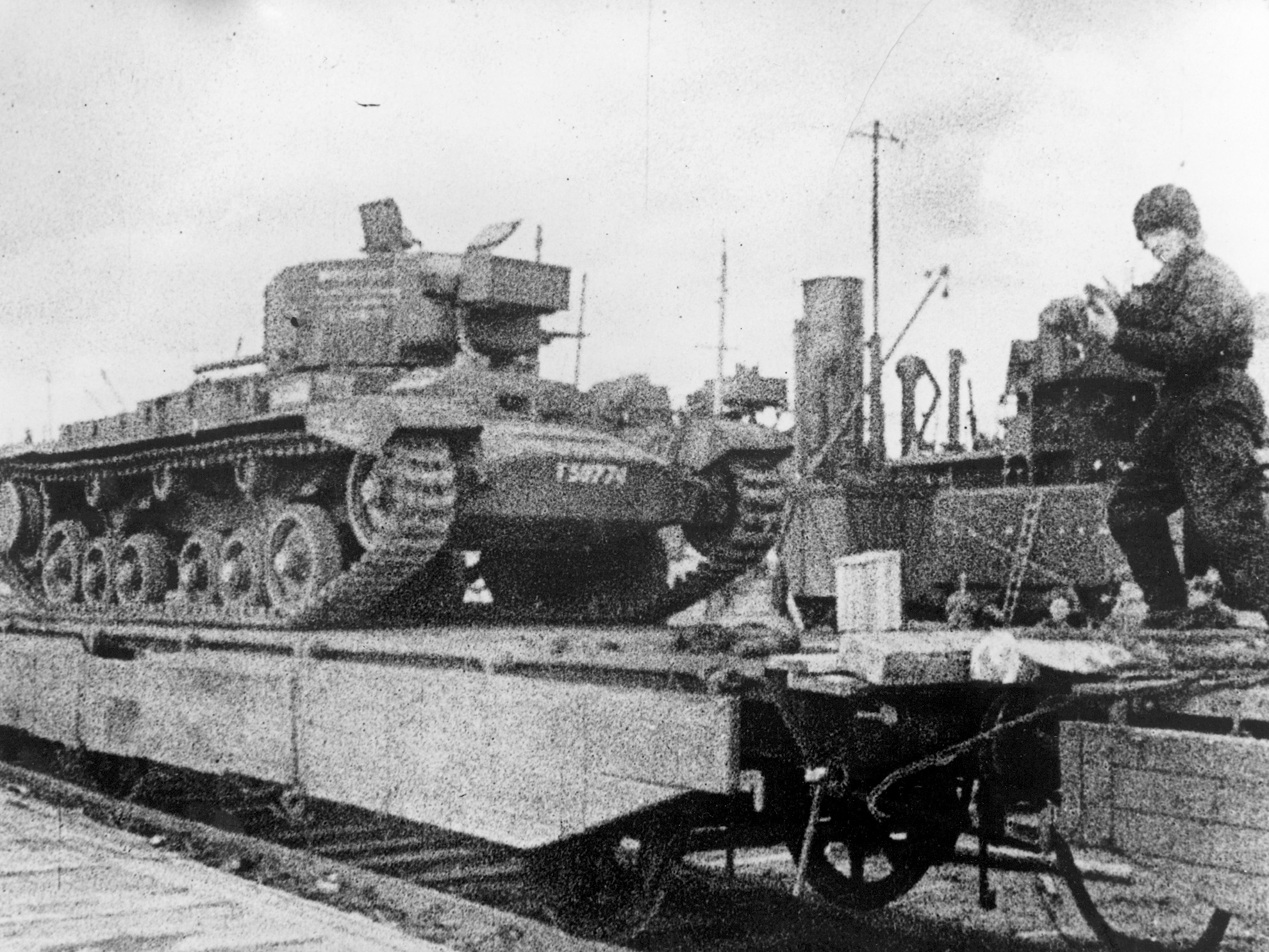

High Stakes As Winter Approaches

With winter approaching, the situation in the Northern Theater became increasingly frustrating for the forces trying to cut the Murmansk supply route. British convoys had already started the “Murmansk Run” in August, and the port was bustling with activity as newly arrived British tanks and aircraft were loaded on trains and sent south to try to stem the German tide. Both German and Finnish commanders knew that time was running out for them to complete their task as the first days of September passed. If Murmansk was to be taken, and its rail line severed, it must be done soon.

Each of the three commanders, Dietl, Feige, and Siilasvuo, now vied with each other for reinforcements and Luftwaffe support to complete their missions. The 6th Gebirgs was still on its way, and some of its units had already been lost when a convoy carrying men and artillery was attacked by a Soviet submarine, followed by an attack by the Royal Navy near the North Cape. The few reinforcements still available to Armee Norwegen were doled out carefully to its various commands.

Desperate Attempt To Cross River

In Dietl’s sector, Gebirgskorps Norwegen made one final attempt to breach the Litsa River. Jumping off on September 8, the 2nd Gebirgs broke out of its small bridgehead near Litsa Bay, clearing out Soviet positions on the south shore of the bay on its left flank and engaging in heavy fighting against the entrenched Russians on its center and right flank. The 3rd Gebirgs Division attacked about seven miles to the south and also made good initial progress.

It was not, however, a one-sided affair. Dietl’s reinforcements had not yet been through the rigors of forest warfare, and both the 388th Infanterie and the 9th SS Infanterie suffered severe casualties as they were attacked from the rear by Soviet positions that had been bypassed in the heavily wooded region. The 388th had been hit so hard that it was forced to withdraw across the Litsa, while the 9th SS broke and ran under the pressure of a Soviet artillery bombardment and ground counterattack.

September 9 found the 2nd Gebirgs Division about three miles inside the Russian line, while the 3rd Gebirgs had gone about four miles. Recovering from the initial assault, the Soviet commanders of the 14th and 52nd Rifle Divisions, and the ad hoc division “Polyarny” (later renamed the 186th Rifle Division) each mounted counterattacks against the advancing Germans. The dense brush and thick forest soon became an area for a deadly game of hide and seek as opponents searched for targets in the eerie, primordial landscape.

Withering Soviet Counterattacks Force German Retreat

By the 10th, both German divisions were brought to a halt by lack of supplies and the stubbornness of the Red Army. It took two days for the 2nd Gebirgs Division to get going again, and another two days before the 3rd Gebirgs could resume the attack. Still plagued by ammunition shortages, the two divisions continued to press on. On the 17th, new Soviet regiments were reported in front of the exhausted Gebirgsjäger. For the next few days the Russians mounted counterattacks against Schlemmer’s and Kreysing’s flanks so that more troops had to be siphoned from the front to prevent the divisions from being cut off.

It was now clear to Dietl that his bid to take Murmansk was at an end. With the increasing Soviet pressure, he ordered Kreysing to withdraw his division to the west bank of the Litsa. Armee Norwegen agreed and canceled the offensive in the northern sector on September 21. The 2nd Gebirgs Division was also ordered to halt and pull back to its bridgehead positions, holding the area as a possible jump-off point for future operations.

Final German-Finnish Offensive

In Armee Norwegen’s central sector, the XXXVI Armeekorps opened its renewed offensive on September 6. Once again, the 169th Infanterie Division was used to batter the Soviet defenses with a frontal attack on the Voyta River line, while the Finns made a frontal assault on Russian positions to the south.

The Finns and two regiments of the 169th made little headway, but Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich-August Schack’s 392nd Infanterie Regiment managed to sweep around the Russian defenses and advance to a strategic position known as Hill 366, about five miles behind the main line. He had a chance to cut the main road from the Voyta to Kandalaksha, if only he could overcome the heavily fortified enemy positions on the hill before Frolov sent more reinforcements to the area.

Schack pushed his men forward and captured Hill 366 on September 7 after a bitter fight. The exhausted infantrymen were entirely spent after the action, and Schack angrily radioed the divisional and corps commanders for more men to help complete his success. Another regiment was promised, but Schack refused to wait. After a night’s rest, he ordered his men to attack Hill 386, about a mile south of his present position. It took two days of heavy fighting to capture the Russian positions there, but the Germans managed to accomplish the feat without the aid of the reinforcing regiment, which was still on its way.

Soviets Retreat And Reinforce

Now that the Voyta Line was threatened from the rear, Frolov ordered a retreat to a new set of prepared positions about five miles to the rear along the Verman River. Leaving a strong rear guard to slow the pursuing Germans and Finns, the men of the 104th and 122nd Rifle Divisions made it back to the Verman Line, where they were reinforced with 5,000 replacements.

When the XXXVI Armeekorps finally reached the Verman Line in mid-September, it was no longer capable of carrying out further offensive operations. Promised reinforcements had not arrived, and the front-line battalions were grossly understrength. Feige’s salient stretched about 50 miles from the Finnish border to the Verman River after two-and-a-half months of battle. He had suffered 9,463 casualties. Basically, XXXVI Armeekorps was worn out. On September 17, Feige received an order from Armee Norwegen to go into defensive mode, effectively ending the drive to Kandalaksha.

Finns Hold Line With Welcome Reinforcements

While Feige and Dietl were making their final attempts to cut the Murmansk rail line, General Siilasvuo had been left to fend for himself. Under constant pressure from Soviet attacks, the Finns were forced to abandon their forward positions and occupy a new line eight miles east of Kesten’ga. When the offensives in the center and the north ran out of steam, Siilasvuo finally began to get reinforcements in mid-September when two more SS battalions and the Nord reconnaissance battalion were shifted to his sector. More units of the Nord Division, as well as an artillery regiment, were also on the way.

With these new forces, Siilasvuo was able to hold his new line and beat off further Soviet attacks. By the end of September, Russian action along his front had been reduced to half-hearted probing attacks, and Soviet prisoners reported that morale was falling because of the losses suffered during the month. Acting on this news, Siilasvuo and von Falkenhorst decided to make one more attempt to take Loukhi.

By the time the necessary supplies and reinforcements were in position for the final push, the Arctic winter had set in. At 0600 on November 1, the attack began. The temperature was minus 4 degrees Fahrenheit as German and Finnish artillery pounded the Russian positions. Groups J and F, which had been upgraded to divisional status, hit the Soviet front while the Nord Division engaged in a sweeping maneuver around the enemy flank.

German Suspicions Mount Regarding Finns

Using their battle-tested “motti” tactics, the Finns were able to infiltrate the Russian line and decimate two regiments of the 88th Rifle Division during the first week of the attack. The Soviets left about 3,000 dead on the field, with another 2,600 taken prisoner. Nord also did well, advancing about five miles before being slowed by another line of enemy defenses.

Heavy fighting took place during the second week of November in steadily falling temperatures. The attack was slowing, but it seemed as if Loukhi was within Siilasvuo’s grasp as the Finns and Germans continued to push forward. Suddenly, however, the Finnish corps commander halted his troops on the pretext of regrouping and mopping up bypassed pockets of resistance, even though his subordinates thought that they were fully capable of fulfilling their primary task.

Von Falkenhorst began to grow increasingly suspicious of the Finns’ reasoning as the month progressed, and grew more so when Mannerheim began pressing him to return all Finnish units under German command to Finnish control. The German general had a right to be leery.

US Threat Changes Finnish Strategy

A message from the still-neutral United States government had reached Helsinki on October 27. It demanded, in no uncertain terms, “Finland should stop all offensive operations and withdraw to the 1939 border.” The note went on to say, “that should material of war sent by the United States to Soviet territory in the north by way of the Arctic Ocean be attacked en route either presumably or allegedly from territory under Finnish control, in the present state of opinion in the United States, such an incident must be expected to bring about an instant crisis between Finland and the United States.”

There was little doubt in Helsinki that the threat was real. Finland, already at war with the Soviet Union, could not afford to antagonize the United States. After a show of public outrage over the note, orders were quietly given and Finnish units either started pulling back or halted in their present positions. Helsinki, through Mannerheim, also demanded that the Finns regain control of their own troops. Without their help, the German dream of cutting the Murmansk supply route was over.

The importance of Murmansk cannot be overlooked, especially during the first year of the Russo-German war. Although the Far East port of Vladivostok and the ports in the Persian Gulf would overshadow Murmansk as the war progressed, it was the Arctic port that was most vital to the Soviet Union in 1941-1942.

Red Army Remained Clothed, Fed And Armed For Duration

From October 1941 to June 1942, 1,285 aircraft, 2,749 tanks, 81,287 machine guns, and 59,455,620 pounds of explosives came through Murmansk. Tons of food from the West also helped feed the Soviet military and civilian populations during the bitter winter of 1941. The failure of the Germans to take the port, a “ridiculous 60 miles” from the Finnish border, meant that British Valentine and Matilda tanks would fight side by side with Russian T-34s and KV 1s during the Moscow counteroffensive. It meant that Red Army troops would go into battle with their stomachs full of Spam and tinned beef, wearing boots and clothing made in England and the United States.

The failure of Hitler and the German High Command to recognize the importance of Murmansk had dramatic consequences during the initial period of the war. Another two or three German divisions could have tipped the scales in 1941, depriving the Russians of their precious supply route. Instead, the Northern Theater was relegated to the backwater of war after the initial assault failed.

The sector remained fairly stagnant until the Soviet summer offensive in 1944, when the Red Army pushed the Germans back into Finland and retook the territory it had lost in 1941. Finland soon sued for peace, forcing the German troops to continue their retreat into Norway or across the Baltic Sea. Murmansk, one of the most valuable pieces of real estate in the Soviet Union, was finally safe.

Pat McTaggart resides in Elkader, Iowa. He is an expert on the bitter fighting between Germany and the Soviet Union during World War II.

What happened to Frolov for disobeying orders ?

Fascinating article on a little-known theater on the Eastern Front.