By Michael E. Haskew

With his troops in a bitter fight with German forces in northern France in the late summer of 1944, General Omar Bradley, commander of the Allied 12th Army Group, could not believe his ears. “Had the pious teetotaling Montgomery wobbled into SHAEF with a hangover, I could not have been more astonished than I was by the daring adventure he proposed,” Bradley remembered. He was of course referring to Operation Market Garden.

Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery had led British and Commonwealth forces to victory in North Africa during the pivotal Battle of El Alamein in 1942 and then chased the German-Italian Panzer Armee Afrika across 1,000 miles of desert. Coupled with the Allied landings of Operation Torch in the west, the Axis forces were caught in a vice and defeated thoroughly by the spring of 1943. Through it all, Montgomery had proceeded with caution, meticulously planned, and made sure that his forces were superior in number to the enemy. The same conduct had characterized his command of the 21st Army Group since the D-Day landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Now, however, it appeared that the cautious, deliberate Montgomery had gone off his rocker. As summer gave way to autumn in 1944, Montgomery had been lobbying General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, to abandon or at least suspend the broad front strategy that had the Allied armies advancing sluggishly toward the German frontier, where the fixed fortifications of the Siegfried Line, or West Wall, were waiting, their garrisons intent on defending the Fatherland.

Montgomery hammered home his concerns. Not only did stiff German resistance promise to become even tougher, but supply lines were stretching. The availability of fuel, ammunition, foodstuffs, and all the elements that keep an advancing military force on the move were becoming scarce.

Montgomery continually argued that the American Third and Canadian First Armies should be halted and resupplied just enough to consolidate their gains and hold their lines against any German counterattack. His own British Second Army and the American First Army would then take center stage, receive the vast majority of war matériel, outflank the Siegfried Line, and rapidly thrust into the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany. A swift and successful offensive under Montgomery’s command would cripple Germany’s capacity to wage war and open a direct route to the Nazi capital of Berlin.

On September 10, 1944, Montgomery outlined his tactical blueprint in a meeting with Eisenhower in Brussels, Belgium. Along with the strategic overview of the offensive, Montgomery proposed Market Garden, a preparatory attack as bold as it was shocking.

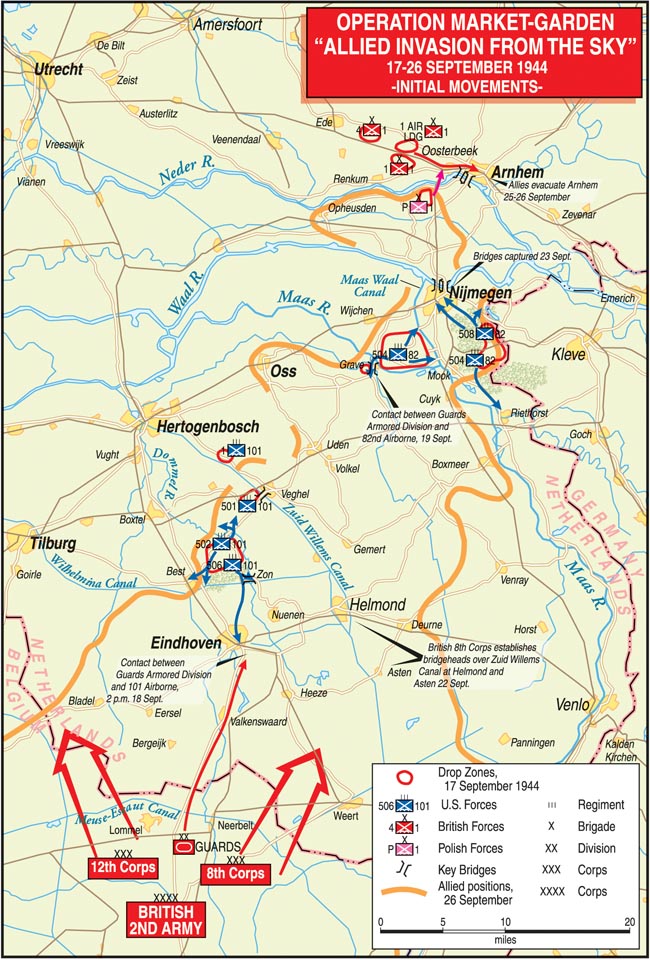

A two-phase offensive, Operation Market Garden called for airborne troops to parachute into the German-occupied Netherlands and seize key bridges across the Maas, Waal, and Lower Rhine Rivers. The paratroopers would hold the bridges until relieved by ground troops racing swiftly through the Netherlands and into Germany. The war might even be won by Christmas 1944 if everything went according to plan.

The seizure of the bridges and adjacent canals was essential for the ground forces to move swiftly. Only a single highway was practical for the drive of approximately 60 miles from the Allied lines in Belgium to the Dutch town of Arnhem. The veteran British XXX Corps would speed down that single road from its bridgehead across the Meuse-Escaut Canal, slicing through expected enemy resistance, relieving the paratroopers at the successive bridges, and then serving as the vanguard of the war-winning offensive that would then thrust like a dagger into Germany.

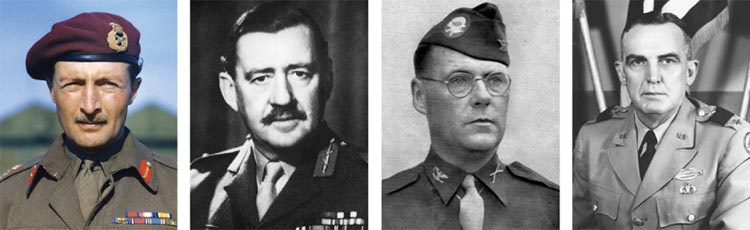

Montgomery’s plan relied on the First Allied Airborne Army, activated just a month earlier, under the command of General Lewis H. Brereton. Brereton commanded the American XVIII Airborne Corps and the headquarters of the I British Airborne Corps. In early September, General Matthew Ridgway was elevated to command the XVIII Airborne Corps, and General James Gavin was promoted to lead the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division. Along with the 82nd, the corps also included the 101st Airborne Division, under General Maxwell Taylor, and the 17th Airborne Division, commanded by General William Miley, as well as the IX Troop Carrier Command and other independent units. The British I Airborne Corps, under General Frederick Arthur Montague “Boy” Browning, included the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions, the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, some special operations troops of the SAS, and allocated air transport formations.

Since taking part in the D-Day invasion and the Normandy Campaign, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions had been refitting and absorbing replacements in England. The 17th Airborne Division, activated in April 1943, arrived in Britain at the end of August 1944, too late for Market Garden. The combat veterans of the 82nd and 101st became the American contribution to Market, the airborne phase of Montgomery’s plan. The British 6th Airborne had also taken part in Operation Overlord and did not return to England until early September, having suffered 4,500 casualties during three months of fighting. Therefore, the 1st Airborne, commanded by General Roy Urquhart, would constitute the British contingent for Market.

As the overall Market Garden plan was developed, the 101st Airborne would secure the southernmost bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal at the town of Son, a pair spanning the Dommel River at St. Odenrode, and then four more over the Aa River near the town of Veghel. The town of Eindhoven was also an objective, while the 101st held open 15 miles of the vital road toward Arnhem for XXX Corps. By the end of Market Garden, the troopers of the 101st would call this stretch of road “Hell’s Highway.”

North of the 101st zone of operations, the 82nd Airborne was to capture the bridge at Grave, the longest in Europe at 1,960 feet. The 82nd would also take one or more of the four bridges across the Maas-Waal Canal, another across the Waal at Nijmegen, and the area around the village of Groesbeek. The final leg of the XXX Corps dash involved a drive from Nijmegen to Arnhem, where the 1st Airborne was to seize three bridges across the Lower Rhine.

Operation Market Garden was scheduled for September 17, just a week after Montgomery and Eisenhower met. When various unit commanders were briefed on the operation, they were told that only light German opposition was expected. General Browning was said to have referred to it as a “party.” Gavin was troubled as he analyzed the 82nd Airborne role.

“The big Nijmegen bridge posed a serious problem,” Gavin observed. “Seizing it with overwhelming strength at the outset would have been meaningless if I did not get at least two other bridges: the big bridge at Grave and at least one of the four over the Canal. Further, even if I captured it, if I had lost all of the high ground that controlled the entire sector, as well as the resupply and glider landing zones, I would be in a serious predicament. Everything depended on the weight and direction of the enemy reaction, and this could not be determined until we were on the ground. The problem was how much could be spared how soon for employment on the bridge.”

The largest airborne operation in history to date, Market-Garden developed in a remarkably short period. Realistically, the time of preparation was inadequate to thoroughly address nagging concerns regarding logistics, supply, and—critically—the level of German resistance expected.

Intelligence reports contradicted the notion that the German Army was in full retreat. In fact, the Dutch Resistance warned that both the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were near Arnhem recovering from fierce fighting in Normandy. Coincidentally, as Market Garden gained momentum the German 59th and 245th Infantry Divisions were relocating from the area of the Fifteenth Army to that of the First Parachute Army, directly in the path of the offensive.

Eisenhower’s chief of staff, General Walter Bedell Smith, relayed mounting concerns about the German presence in the Netherlands to Montgomery. The response was dismissive, uncharacteristically bold for Montgomery.

Smith wrote, “Montgomery simply waved my objections airily aside.” Urquhart brought his own worries to Browning and was told that tanks seen in reconnaissance photos were probably just being repaired. Urquhart was then advised to take a short leave and rest at his home, only hours before the first transport aircraft took off.

Market was designated a daylight operation. Allied air supremacy would minimize interference from German fighter planes, while the desire for a strong drop pattern and the coordination of air and ground movement would be facilitated. The fresh memory of the scattered, nocturnal Normandy jump outweighed the fears of more intense enemy antiaircraft fire that would doubtless be encountered. With Market more than 20,000 troopers would eventually be delivered to drop zones by parachute and more than 14,000 by glider along with 1,736 vehicles, 3,342 tons of ammunition, and 263 artillery pieces.

To minimize exposure to antiaircraft fire and deliver the three airborne divisions most efficiently, it was decided that troop carrier groups would take the 1st and 82nd Airborne Divisions, landing to the north, on a flight path across the estuary of the Scheldt and Maas Rivers, above roughly 80 miles of enemy-held territory. Those carrying the troopers of the 101st would fly a longer, southerly route mainly over Belgium and limiting the transit over German territory to 65 miles.

Since Operation Overlord the IX Troop Carrier Command had replenished its airlift capacity to roughly that of D-Day. The 101st Airborne was supplied with 424 C-47s for paratroopers along with 70 tow planes and gliders, while the 82nd received 480 troop transports and 50 gliders and tow planes. The 1st Airborne was allocated 145 C-47s and 358 gliders and tow planes. Nearly 1,900 Allied fighter aircraft were committed to escort duty and antiaircraft suppression, while early on the morning of September 17, more than 1,400 bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force and Royal Air Force Bomber Command were scheduled to hit ground targets in the paths of transports and around the drop zones.

At 10:25 am on September 17, the first American C-47s carrying pathfinders of the 101st Airborne Division began smoothly lifting off at 10-minute intervals. Flying toward drop zones north of Eindhoven, the 442nd and 435th Troop Carrier Groups got 45 planes into the air in five minutes and 32 planes aloft and in formation in 15 minutes, respectively. Carrying the 1st Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), transports of the 424th Troop Carrier Wing dropped 42 sticks of troopers three miles northwest of their assigned drop zone, but a tight drop pattern allowed the battalion to assemble 90 percent of its men and equipment in less than 45 minutes.

The 442nd and 436th placed the 506th PIR right on target. One transport was shot down along the way, but the others delivered approximately 2,200 men with such accuracy that the regimental command post was functioning and 80 percent of the troopers were assembled within an hour. Only 24 troopers that jumped sustained injuries. The war journal of the 506th called the event “an ideal jump, better than any combat or practice jump executed.” The 502nd PIR was also dropped accurately, assembling within an hour.

Six groups of the 50th and 52nd Troop Carrier Wings carried the 7,250 troopers of the 82nd Airborne Division to drop zones near the Maas River south of Nijmegen. The 315th Troop Carrier Group dropped 78 sticks of paratroopers within 1,500 yards of its designated pathfinder beacons, and all of the 504th PIR except Company E, 1st Battalion came to earth in the area.

C-47s of the 440th and 441st Troop Carrier Groups dropped two battalions and the headquarters of the 508th PIR just off the northern edge of its assigned drop zone, while the 3rd Battalion came down inside its eastern perimeter. In just over one and a half hours, the regiment was 90 percent assembled. The commander of the 3rd Battalion later reported, “We could not have landed better under any circumstances.”

Meanwhile, the British 1st Airborne dropped along the north bank of the Lower Rhine, eight miles west of Arnhem. General Urquhart’s Red Devils moved out swiftly toward their vital objectives. Sporadic sniper fire broke out within minutes. German resistance steadily mounted—and for good reason. The British had come to earth only two miles from the headquarters of German Army Group B. Field Marshal Walther Model believed he was the target of a kidnapping and hurried to the headquarters of General Wilhelm Bittrich, commander of the II SS Panzer Corps.

![By Michael E. Haskew With his troops in a bitter fight with German forces in northern France in the late summer of 1944, General Omar Bradley, commander of the Allied 12th Army Group, could not believe his ears. “Had the pious teetotaling Montgomery wobbled into SHAEF with a hangover, I could not have been more astonished than I was by the daring adventure he proposed,” Bradley remembered. He was of course referring to Operation Market Garden. Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery had led British and Commonwealth forces to victory in North Africa during the pivotal Battle of El Alamein in 1942 and then chased the German-Italian Panzer Armee Afrika across 1,000 miles of desert. Coupled with the Allied landings of Operation Torch in the west, the Axis forces were caught in a vice and defeated thoroughly by the spring of 1943. Through it all, Montgomery had proceeded with caution, meticulously planned, and made sure that his forces were superior in number to the enemy. The same conduct had characterized his command of the 21st Army Group since the D-Day landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944. Now, however, it appeared that the cautious, deliberate Montgomery had gone off his rocker. As summer gave way to autumn in 1944, Montgomery had been lobbying General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, to abandon or at least suspend the broad front strategy that had the Allied armies advancing sluggishly toward the German frontier, where the fixed fortifications of the Siegfried Line, or West Wall, were waiting, their garrisons intent on defending the Fatherland. Montgomery hammered home his concerns. Not only did stiff German resistance promise to become even tougher, but supply lines were stretching. The availability of fuel, ammunition, foodstuffs, and all the elements that keep an advancing military force on the move were becoming scarce. Montgomery continually argued that the American Third and Canadian First Armies should be halted and resupplied just enough to consolidate their gains and hold their lines against any German counterattack. His own British Second Army and the American First Army would then take center stage, receive the vast majority of war matériel, outflank the Siegfried Line, and rapidly thrust into the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany. A swift and successful offensive under Montgomery’s command would cripple Germany’s capacity to wage war and open a direct route to the Nazi capital of Berlin. On September 10, 1944, Montgomery outlined his tactical blueprint in a meeting with Eisenhower in Brussels, Belgium. Along with the strategic overview of the offensive, Montgomery proposed Market Garden, a preparatory attack as bold as it was shocking. During Operation Market Garden, The American 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions were assigned to capture bridges in the Netherlands to allow XXX Corps to link up with the British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem. A two-phase offensive, Operation Market Garden called for airborne troops to parachute into the German-occupied Netherlands and seize key bridges across the Maas, Waal, and Lower Rhine Rivers. The paratroopers would hold the bridges until relieved by ground troops racing swiftly through the Netherlands and into Germany. The war might even be won by Christmas 1944 if everything went according to plan. The seizure of the bridges and adjacent canals was essential for the ground forces to move swiftly. Only a single highway was practical for the drive of approximately 60 miles from the Allied lines in Belgium to the Dutch town of Arnhem. The veteran British XXX Corps would speed down that single road from its bridgehead across the Meuse-Escaut Canal, slicing through expected enemy resistance, relieving the paratroopers at the successive bridges, and then serving as the vanguard of the war-winning offensive that would then thrust like a dagger into Germany. Montgomery’s plan relied on the First Allied Airborne Army, activated just a month earlier, under the command of General Lewis H. Brereton. Brereton commanded the American XVIII Airborne Corps and the headquarters of the I British Airborne Corps. In early September, General Matthew Ridgway was elevated to command the XVIII Airborne Corps, and General James Gavin was promoted to lead the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division. Along with the 82nd, the corps also included the 101st Airborne Division, under General Maxwell Taylor, and the 17th Airborne Division, commanded by General William Miley, as well as the IX Troop Carrier Command and other independent units. The British I Airborne Corps, under General Frederick Arthur Montague “Boy” Browning, included the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions, the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade, some special operations troops of the SAS, and allocated air transport formations. LEFT TO RIGHT: British General Frederick “Boy” Browning led the I Airborne Corps during Market Garden. Lt. Col. John Frost commanded the 2nd Parachute Battalion in the heroic but futile effort at Arnhem. Colonel Roy Lindquist commanded the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division during Operation Market Garden. Colonel Robert Sink led the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. Since taking part in the D-Day invasion and the Normandy Campaign, the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions had been refitting and absorbing replacements in England. The 17th Airborne Division, activated in April 1943, arrived in Britain at the end of August 1944, too late for Market Garden. The combat veterans of the 82nd and 101st became the American contribution to Market, the airborne phase of Montgomery’s plan. The British 6th Airborne had also taken part in Operation Overlord and did not return to England until early September, having suffered 4,500 casualties during three months of fighting. Therefore, the 1st Airborne, commanded by General Roy Urquhart, would constitute the British contingent for Market. As the overall Market Garden plan was developed, the 101st Airborne would secure the southernmost bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal at the town of Son, a pair spanning the Dommel River at St. Odenrode, and then four more over the Aa River near the town of Veghel. The town of Eindhoven was also an objective, while the 101st held open 15 miles of the vital road toward Arnhem for XXX Corps. By the end of Market Garden, the troopers of the 101st would call this stretch of road “Hell’s Highway.” North of the 101st zone of operations, the 82nd Airborne was to capture the bridge at Grave, the longest in Europe at 1,960 feet. The 82nd would also take one or more of the four bridges across the Maas-Waal Canal, another across the Waal at Nijmegen, and the area around the village of Groesbeek. The final leg of the XXX Corps dash involved a drive from Nijmegen to Arnhem, where the 1st Airborne was to seize three bridges across the Lower Rhine. Operation Market Garden was scheduled for September 17, just a week after Montgomery and Eisenhower met. When various unit commanders were briefed on the operation, they were told that only light German opposition was expected. General Browning was said to have referred to it as a “party.” Gavin was troubled as he analyzed the 82nd Airborne role. “The big Nijmegen bridge posed a serious problem,” Gavin observed. “Seizing it with overwhelming strength at the outset would have been meaningless if I did not get at least two other bridges: the big bridge at Grave and at least one of the four over the Canal. Further, even if I captured it, if I had lost all of the high ground that controlled the entire sector, as well as the resupply and glider landing zones, I would be in a serious predicament. Everything depended on the weight and direction of the enemy reaction, and this could not be determined until we were on the ground. The problem was how much could be spared how soon for employment on the bridge.” The largest airborne operation in history to date, Market-Garden developed in a remarkably short period. Realistically, the time of preparation was inadequate to thoroughly address nagging concerns regarding logistics, supply, and—critically—the level of German resistance expected. British General Miles Dempsey, commander of the British Second Army, confers with Brig. Gen. James M. Gavin, commander of the American 82nd Airborne Division as the two consult a map of the Dutch city of Nijmegen. Intelligence reports contradicted the notion that the German Army was in full retreat. In fact, the Dutch Resistance warned that both the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions were near Arnhem recovering from fierce fighting in Normandy. Coincidentally, as Market Garden gained momentum the German 59th and 245th Infantry Divisions were relocating from the area of the Fifteenth Army to that of the First Parachute Army, directly in the path of the offensive. Eisenhower’s chief of staff, General Walter Bedell Smith, relayed mounting concerns about the German presence in the Netherlands to Montgomery. The response was dismissive, uncharacteristically bold for Montgomery. Smith wrote, “Montgomery simply waved my objections airily aside.” Urquhart brought his own worries to Browning and was told that tanks seen in reconnaissance photos were probably just being repaired. Urquhart was then advised to take a short leave and rest at his home, only hours before the first transport aircraft took off. Market was designated a daylight operation. Allied air supremacy would minimize interference from German fighter planes, while the desire for a strong drop pattern and the coordination of air and ground movement would be facilitated. The fresh memory of the scattered, nocturnal Normandy jump outweighed the fears of more intense enemy antiaircraft fire that would doubtless be encountered. With Market more than 20,000 troopers would eventually be delivered to drop zones by parachute and more than 14,000 by glider along with 1,736 vehicles, 3,342 tons of ammunition, and 263 artillery pieces. To minimize exposure to antiaircraft fire and deliver the three airborne divisions most efficiently, it was decided that troop carrier groups would take the 1st and 82nd Airborne Divisions, landing to the north, on a flight path across the estuary of the Scheldt and Maas Rivers, above roughly 80 miles of enemy-held territory. Those carrying the troopers of the 101st would fly a longer, southerly route mainly over Belgium and limiting the transit over German territory to 65 miles. The jump master of a group of American airborne troops inspects each trooper prior to boarding the C-47 transport plane that will carry them over the Dutch countryside to an assigned drop zone on September 17, 1944. Since Operation Overlord the IX Troop Carrier Command had replenished its airlift capacity to roughly that of D-Day. The 101st Airborne was supplied with 424 C-47s for paratroopers along with 70 tow planes and gliders, while the 82nd received 480 troop transports and 50 gliders and tow planes. The 1st Airborne was allocated 145 C-47s and 358 gliders and tow planes. Nearly 1,900 Allied fighter aircraft were committed to escort duty and antiaircraft suppression, while early on the morning of September 17, more than 1,400 bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force and Royal Air Force Bomber Command were scheduled to hit ground targets in the paths of transports and around the drop zones. At 10:25 am on September 17, the first American C-47s carrying pathfinders of the 101st Airborne Division began smoothly lifting off at 10-minute intervals. Flying toward drop zones north of Eindhoven, the 442nd and 435th Troop Carrier Groups got 45 planes into the air in five minutes and 32 planes aloft and in formation in 15 minutes, respectively. Carrying the 1st Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), transports of the 424th Troop Carrier Wing dropped 42 sticks of troopers three miles northwest of their assigned drop zone, but a tight drop pattern allowed the battalion to assemble 90 percent of its men and equipment in less than 45 minutes. The 442nd and 436th placed the 506th PIR right on target. One transport was shot down along the way, but the others delivered approximately 2,200 men with such accuracy that the regimental command post was functioning and 80 percent of the troopers were assembled within an hour. Only 24 troopers that jumped sustained injuries. The war journal of the 506th called the event “an ideal jump, better than any combat or practice jump executed.” The 502nd PIR was also dropped accurately, assembling within an hour. Six groups of the 50th and 52nd Troop Carrier Wings carried the 7,250 troopers of the 82nd Airborne Division to drop zones near the Maas River south of Nijmegen. The 315th Troop Carrier Group dropped 78 sticks of paratroopers within 1,500 yards of its designated pathfinder beacons, and all of the 504th PIR except Company E, 1st Battalion came to earth in the area. C-47s of the 440th and 441st Troop Carrier Groups dropped two battalions and the headquarters of the 508th PIR just off the northern edge of its assigned drop zone, while the 3rd Battalion came down inside its eastern perimeter. In just over one and a half hours, the regiment was 90 percent assembled. The commander of the 3rd Battalion later reported, “We could not have landed better under any circumstances.” Meanwhile, the British 1st Airborne dropped along the north bank of the Lower Rhine, eight miles west of Arnhem. General Urquhart’s Red Devils moved out swiftly toward their vital objectives. Sporadic sniper fire broke out within minutes. German resistance steadily mounted—and for good reason. The British had come to earth only two miles from the headquarters of German Army Group B. Field Marshal Walther Model believed he was the target of a kidnapping and hurried to the headquarters of General Wilhelm Bittrich, commander of the II SS Panzer Corps. British troopers of the 1st Airborne Division, commanded by General Roy Urquhart, gather equipment after coming to earth in the Netherlands during the opening moments of ill-fated Operation Market Garden. Bittrich, a sharp tactician, sensed the situation and was already responding with great insight. He ordered the tanks of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions to Arnhem and Nijmegen, respectively. German troops cut the roads eastward to Arnhem and blocked the advance of the 1st Airborne toward the city. Only the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade, 500 men under Lt. Col. John D. Frost, reached the northern end of the main bridge across the Lower Rhine at Arnhem. These paras were set upon by superior German forces but held on grimly, waiting in vain for the arrival of the remainder of the 1st Airborne Division, which was stymied on the roads. Due to the stiff resistance west of Arnhem, Operation Market Garden was doomed to fail. The 1st Airborne Division fought gallantly for 10 days, but of the nearly 10,000 paratroopers Urquhart had taken into the vicinity of Arnhem just over 2,000 evaded death or capture. Frost’s valiant command held out at the Arnhem highway bridge for nearly four days before surrendering. Fewer than 50 men of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade managed to escape. Only two battalions of the 101st Airborne Division failed to land in or near their drop zones on September 17. Dropping near Son, the 506th PIR, under Colonel Robert Sink, was to capture a bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal and continue south to Eindhoven. The 502nd PIR, commanded by Colonel John H. Michaelis, was to establish a perimeter around its drop zone north of the 506th for later use as a glider-landing zone. Then, it was to capture more bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal near the town of Best and one of those spanning the Dommel. Farther north, Colonel Howard Johnson’s 501st was to capture four road and rail bridges on the Willems Canal and the Aa River near Veghel. The 501st PIR made rapid progress. Lt. Col. Harry W.O. Kinnard, commanding the 1st Battalion, one of the two that had dropped in the wrong place, set off toward Veghel as some of the troopers commandeered bicycles and trucks to speed the advance. When Kinnard reached Veghel a handful of his men had already secured the railroad bridge over the Aa. The 2nd Battalion seized three bridges at Veghel, while the 3rd Battalion took the town of Eerde and cut the Veghel-St. Oedenrode highway, covering the regiment’s rear. The 501st secured all of its September 17 objectives in about three hours, capturing scores of prisoners. In his haste to move against Veghel, though, Kinnard had not taken all his battalion’s equipment along. He left 46 men under Captain W.S. Burd to bring the equipment and several paratroopers who had been injured during the jump forward at a slower pace. Burd’s detachment was attacked by a strong German force and pushed back to a single building. When word of Burd’s plight reached Kinnard, Colonel Johnson allowed him to send a platoon to the rescue. The attempt failed, and the survivors of Burd’s group were captured. German troops were in the vicinity of Arnhem in much greater strength than anticipated, and soon the British paras in the town were isolated and fighting for their lives. These German soldiers are digging in near the embattled Dutch city on the Lower Rhine River. The other battalion of the 101st dropped outside its zone was the 1st of the 502nd led by Lt. Col. Patrick Cassidy. Cassidy’s men nevertheless swept into St. Oedenrode, commanding a major highway and a bridge across the Dommel. They occupied the town, killed 20 Germans, and took another 58 prisoner. General Taylor, commanding the 101st, recognized the importance of the rail and highway bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal near Best. Although they were not on the direct XXX Corps line of advance, Taylor considered them vital in strengthening his defensive perimeter and knew that they could be used if the route through Son was blocked. Captain Robert E. Jones of Company H, 502nd PIR, started toward these bridges and immediately took heavy German fire. Jones sent a patrol under Lieutenant Edward L. Wierzbowski forward. The Americans came within sight of the highway bridge but were forced to dig in, their strength reduced to three officers and 15 men. Commanding the 3rd Battalion, 502nd, Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, who had earned the Medal of Honor in Normandy, started out with the rest of his battalion to find Jones and Company H at about 6 PM, but the effort was halted by darkness. The next morning, Cole spoke over his radio to a pilot flying nearby. The pilot asked for orange recognition panels to be placed on the ground near the battalion command post, and the officer decided to handle the chore himself. Cole raised his head slightly, shielding his eyes against the sun and looking overhead for the plane. A single shot rang out. Cole fell dead from a sniper’s bullet fired from a farmhouse 300 yards away. The capture of Best ultimately required two more days and a much larger force, including British tanks and two more battalions of troops. Pfc. Class Joe E. Mann was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the fight for Best. Like Cole, he was killed by a German sniper. South of Son, General Taylor accompanied the 1st Battalion, 506th toward the Wilhelmina Canal road bridge. Just south of the town near the edge of the Zonsche Forest, German 88mm guns opened up on the paratroopers. More 88s zeroed in on the other two battalions of the 506th, led by Colonel Sink. Paratrooper Don Burgett of the 1st Battalion recalled the vicious battle for Son. “We organized and we began to charge the guns,” he related. “The only way we were going to survive was to knock out the 88s even though a lot of us were going to die trying to do it. As we were running toward them, they fired at us at point-blank range. We overran their positions. There were several 88s. They were sandbagged and dug in and used for antiaircraft. A trooper from D Company got in close enough and fired a bazooka and knocked out one of the guns.” Both groups of the 506th advanced toward the bridge. “We overran the 88s, took the German gunners prisoner, and someone said, ‘Let’s take the bridge,’” Burgett continued. “We started to run toward the bridge. We were within yards of the bridge when the Germans blew it up. It went off with quite a force…. We hit the ground. I rolled over on my back because everything got real quiet, and I saw the debris in the air. I remember seeing this tiny straw that was turning slowly way up in the air and as it hit its maximum trajectory and it started to come down, it became larger and larger. About halfway down we realized the size of this thing. It was probably about two feet wide and forty feet long. There was no place to run. When it hit the ground, the ground shook like Jell-O.” A paratrooper of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division has just released his parachute harness and is running toward an assembly area, while another, in the foreground, has just landed. The parachutes of many other American troopers billow in the distance as Operation Market Garden begins. With the Son bridge blown to pieces, the capture of Eindhoven was slowed. However, XXX Corps halted that evening at Valkenswaard, six miles away. Unexpectedly heavy German resistance had upset the timetable for Garden, the critical ground phase of the offensive. The narrow road was elevated above the surrounding fields, and British tanks were silhouetted against the sun, perfect targets for German antitank weapons. Each time a machine-gun nest erupted, the narrow British column was required to halt and deploy infantry to remove the threat. By the time XXX Corps got to Eindhoven the next day, the town belonged to the 101st Airborne Division. At nightfall on the 17th, the 101st was in control of Veghel, St. Oedenrode, and Son. Although the 502nd had encountered tough German troops around Best, the objective there was secondary. With a few more hours of hard fighting, the 101st would have its stretch of Hell’s Highway completely open. As soon as they saw the first Allied soldiers, jubilant Dutch civilians had welcomed them as liberators. Early on the morning of September 18, the 506th destroyed a pair of German 88s and pushed into Eindhoven. While throngs of citizens celebrated their apparent liberation in the streets, the paratroopers disarmed a handful of Germans. One American officer recalled, “The reception was terrific. The air seemed to reek with hate for the Germans....” Finally, at 5 pm on the 18th, the leading elements of XXX Corps rumbled through Eindhoven virtually without stopping. At Son, Canadian engineers, who had been notified that the existing bridge had been destroyed, worked through the night to deploy a prefabricated Bailey bridge. At 6:45 am on the 19th, the tanks of XXX Corps rumbled across the Wilhelmina Canal, but they were 33 critical hours behind schedule. Later on the morning of September 19, XXX Corps was across the Willems Canal and the Aa River at Veghel, moving into the zone of the 82nd Airborne. In the 101st sector, the primary job became holding the narrow corridor of hope open against German counterattacks. While Allied armor was advancing northward, it was imperative to keep the road open to facilitate the flow of troops and supplies. The Germans fought back viciously against 101st defensive positions around Eindhoven, Son, St. Oedenrode, and Veghel. General Taylor likened the actions to the bushwhacking style of Indian fighting in the Old West. The Germans attacked repeatedly, cutting the narrow road. They were driven away each time. On the 22nd, the Germans mounted a counterattack against Veghel supported by heavy artillery and aircraft. The attack was not completely beaten back for two days. “It was a very depressing atmosphere listening to the civilians moan, shriek, sing hymns and say their prayers,” wrote Daniel Kenyon Webster of E Company, 506th PIR, remembering the steady concussions of artillery shells hammering the town. As a column of XXX Corps vehicles comes under attack by the Germans on the road between Eindhoven and Nijmegen, British ground troops take cover in a ditch along the roadside. Eventually, tanks and Royal Air Force Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers were called in to break the German resistance. Webster and Private Don Wiseman hunkered deeply into a foxhole. “Wiseman and I sat in our corners and cursed,” Webster offered. “Every time we heard a shell come over, we closed our eyes and put our heads between our legs. Every time the shells went off, we looked up and grinned at each other.” On September 24, the Germans shot up a British column on Hell’s Highway at Koevering northeast of Eindhoven. Burgett remembered, “Germans brought up some 40mm cannons and they had some self-propelled guns and they shot the British who were lined up on the side of the road and they were brewing tea in these five-gallon tins and the Germans just opened up on them. They killed over 300. “When we got down to Koevering, the trucks were still burning,” continued Burgett. “We went into the attack immediately. I remember we killed two Germans in a haystack. Then we made an attack west across the road to a farmhouse. The farmhouse was set on fire. We went into the German side and we drove them back.” When it became apparent that Market Garden was a strategic failure, the men of the 101st Airborne were able to assert that they had done their part. The division had killed many Germans and captured 3,511. Its own losses were 2,110 dead, wounded, and missing. General Taylor recognized that the 101st’s hold on the highway corridor was threatened from both east and west and dependent on the movement of the British VIII and XII Corps coming up on the flanks to assist in its defense. Responding to German probing attacks, Taylor launched limited offensive actions of his own, keeping the enemy off balance and delaying a decisive blow against the roadway to the north. Although most troopers of the 101st expected to pull out of the line at the end of September, the division was placed under the control of the British XII Corps on the 28th and transferred north to the front line in an area known as “the Island,” a three-mile strip of land between the Lower Rhine and the Waal. Due to the heavy casualties absorbed during Market Garden, the British were sorely pressed for troops, and both the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions found themselves in positions that resembled the static trench lines of World War I. They were regularly subjected to artillery duels between British and German guns. There were also sharp firefights. On the night of October 5, a platoon of Company E, 506th PIR, supported by a detachment from Company F, mauled two companies of German SS troops attempting to infiltrate American lines in support of an attack by the 363rd Volksgrenadier Division. Captain Richard Winters, who had earned the Distinguished Service Cross in Normandy and now led Company E, commanded his 35 men brilliantly, demonstrating bravery and coolness under fire. Moving along a road adjacent to a dike near the banks of the Lower Rhine, Winters shot a German who was only three yards away and then opened up on a large mass of enemy troops. “The movements of the Germans seemed to be unreal to me,” he reflected. “When they rose up, it seemed to be so slow, when they turned to look over their shoulders at me, it was in slow motion, when they started to raise their rifles to fire at me, it was in slow, slow motion. I emptied the first clip [eight rounds] and, still standing in the middle of the road, put in a second clip and, still shooting from the hip, emptied that clip into the mass.” Winters remembered that particular fight as the “highlight of all E Company actions for the entire war, even better than D-Day, because it demonstrated Easy’s overall superiority in every phase of infantry tactics: patrol, defense, attack under a base of fire, withdrawal, and above all, superior marksmanship with rifles, machine gun, and mortar fire.” The 101st Airborne Division held its positions on the Island until late November, when it was withdrawn to Camp Mourmelon, outside the French village of Mourmelon-le-Grand. From the Market Garden drop until its last troopers were relieved, the 101st had spent 72 days in combat areas. In addition to its Market Garden losses, the defensive fighting at the Island cost the Screaming Eagles another 1,682 casualties. The men of the 101st had experienced combat for the first time on D-Day. They had fought gallantly as tough, combat-wise veterans in Holland. However, their sternest test and their finest hour were yet to come during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944 at the Belgian crossroads town of Bastogne. An M4 Sherman “Firefly” tank, upgunned with the British 17-pounder gun, makes its way past three other tanks that have been knocked out by German guns. The narrow road that XXX Corps traveled toward Arnhem was hazardous due to heavy enemy resistance. While considering the role his 82nd Airborne Division was assigned in Operation Market Garden, 37-year-old Brig. Gen. Gavin understood a few things clearly. His division would attempt to take each of its objectives in a single day. The 82nd would also hold these objectives for at least 36 hours since relief from XXX Corps could not realistically be expected until sometime late on September 18. Further, Gavin could easily see from maps that the terrain surrounding the towns and bridges that were critical to the offensive were dominated by a triangular ridgeline running from just southeast of Nijmegen past a resort hotel called the Berg en Dal through the towns of Wyler, Groesbeek, and Riethorst along the Maas River. Roughly eight miles long and 300 feet high, the ridge provided a clear view and fields of fire for a tremendous distance. It terminated to the east along the Dutch-German frontier, disappearing into the deep, almost impenetrable forest of the Reichswald. Giving priority to the high ground, Gavin and General Browning, who served as deputy commander of the First Allied Airborne Army, initially agreed that all other objectives should be taken before securing the Nijmegen bridge over the Waal. Later, Gavin concluded that he could spare a single battalion to take a stab at the bridge before the Germans reacted in force. Gavin ordered Colonel Roy E. Lindquist, commander of the 508th PIR, to send the single battalion against the span at Nijmegen while the rest of the regiment secured six miles of the ridgeline from Nijmegen south to Groesbeek. The 508th was also to assist in the capture of bridges across the Maas-Waal Canal at Hininghutje and Hatert, cut the approaches from the north, and safeguard the glider-landing zone south of Wyler. Colonel William E. Eckman’s 505th PIR was primarily tasked with capturing Groesbeek and the ridgeline south to the town of Kiekberg at Hill 77.2 and securing the second glider-landing zone. Meanwhile, Colonel Reuben Tucker’s 504th PIR was to capture the big bridge across the Maas River near the town of Grave, capture the bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal at Malden and Heumen, and prevent the Germans from shuttling troops between the Maas and the Maas-Waal Canal. Encountering light resistance around the drop zones, the troopers of the 82nd Airborne moved out. The capture of the Grave bridge was eased unexpectedly when 16 troopers of the 504th aboard a single C-47 were delayed a few seconds in jumping. When the green light was illuminated, Lieutenant John S. Thompson, commanding the stick, noticed the plane was above a cluster of buildings. He decided to hold off a moment and attempt to come down in a nearby field. After Thompson’s men parachuted, they came to earth just 700 yards off the southern end of the bridge. With the rest of the 504th over a mile away, Thompson acted quickly. Dashing through sporadic rifle fire and crouching in drainage ditches, the troopers blasted a flak tower mounting a 20mm gun with a pair of bazooka rounds, cut wires to demolition charges, and took control of the southern end of the bridge. On the other bank of the Maas the remainder of Thompson’s battalion moved toward the Grave bridge, shrugging off fire from a single flak gun near the water’s edge. One of the principal objectives of Market Garden was secured in just three hours. American patrols sent into Grave found that the Germans had pulled out. The townspeople were celebrating with the popular tune “Tiperrary.” Commanding a battalion of the 504th PIR, Major Willard E. Harrison sent single companies to seize bridges over the Maas-Waal Canal at Malden and Heumen. At Heumen, the Germans poured rifle and machine-gun fire from an island in the canal, but eight men crept forward to place covering fire on the island. Two officers, a radio operator, and a corporal rushed the bridge. One man was shot, but six more troopers rowed a small boat across the canal and joined the three who had survived the deadly run. When darkness fell, a reinforced patrol sprinted across a footbridge, overwhelming the Germans on the island. Leading the company at Heumen, Captain Thomas Helgeson expected the Germans to blow the bridge sky high, but inexplicably it stood. Charges were spotted, and a demolition team cut the wires. Just as a squad of troopers reached the river at Malden, that bridge exploded in a shower of debris. The bridge at Heumen later became XXX Corps’ primary northward route. Troopers of the 504th and 508th found the bridge over the Maas-Waal Canal at Hatert demolished. When more 508th men approached the last canal bridge at Honinghutje before daylight the next morning the Germans detonated explosives that failed to destroy the span but rendered it unusable. One battalion of the 508th PIR set up roadblocks on the highway from Mook to Nijmegen to block any German move south, while a second occupied the northern end of the long ridge from the outskirts of Nijmegen to the Berg en Dal resort, a distance of three and a half miles. Light resistance was encountered in this effort, and the following day the battalion cut the Kleve-Nijmegen Highway with the occupation of the village of Beek at the base of the ridge. A German soldier drives a captured American Jeep while several SdKfz 250/1 armored cars are also shown laden with infantrymen who have hitched rides. Initially surprised by the Market Garden offensive, the Germans rallied quickly and fought back ferociously. Lieutenant Colonel Shields Warren, Jr., led the 1st Battalion, 508th in the quick strike at the highway bridge across the formidably wide Waal at Nijmegen. An apparent misinterpretation of Gavin’s order, which the general later remembered as instructing a battalion to advance on the big bridge “without delay after landing,” led Colonel Lindquist to rely more directly on the original plan to secure other objectives prior to any move against the highway bridge across the Waal. Lindquist ordered Warren to organize defensive positions at De Ploeg, a suburb of Nijmegen, establishing communications with other positions around the Berg en Dal. More than three hours were required for Warren to pull his troops together and reach De Ploeg. By the time the first assignment from Lindquist was completed it was 6:30 pm. Dutch civilians reported to Lindquist that only 18 Germans were standing watch at the southern end of the highway bridge, and the battalion commander sent a reinforced patrol consisting of his intelligence section and a rifle company into Nijmegen to assess the situation. Due to a radio malfunction, the patrol was unable to send any information to Warren until the next day. Gavin sensed an opportunity. He prodded Lindquist with a terse order “to delay not a second longer and get the bridge as quickly as possible with Warren’s battalion.” Seven precious hours slipped away before a concerted effort to seize the Nijmegen bridge went forward. After a Dutch civilian offered to guide his battalion into town to meet with resistance leaders, Warren instead instructed Companies A and B to link up southeast of Nijmegen at 7 pm and follow the Dutchman to the bridge. Company A reached the designated point on time; however, Company B got lost along the way. An hour later when he could wait no longer, Warren left a guide for Company B and set out with Company A toward the highway bridge. Advancing through the darkened streets of Nijmegen, the troopers cleared houses on the edge of town. Finding no Germans, they continued their stealthy approach until they reached the Keizer Karel Plein, a traffic circle in the center of Nijmegen. At approximately 10 pm, the staccato of automatic weapons halted their progress. General Bittrich’s insight was about to cost the Americans dearly. While the paratroopers took cover against the small arms fire, they heard engines roaring forward, followed quickly by squeaking brakes and the sounds of men jumping from trucks. The leading elements of the 10th SS Panzer Division had arrived in Nijmegen. The opportunity to capture the highway bridge against light opposition evaporated. Hours earlier, the Germans in Nijmegen numbered a few troops of inferior combat efficiency. These newly arrived SS men were battle-hardened veterans. Company A tried twice to take the southern end of the bridge, and twice they were thrown back by counterattacking Germans. The effort to take the Nijmegen bridge on September 17 petered out. Gavin arrived and determined that the paratroopers were getting nowhere. He ordered them to “withdraw from close proximity to the bridge and reorganize.” A small patrol led by Captain Jonathan Adams, Jr., received word from the Dutch Resistance that detonation equipment for the explosive charges wired to the bridge was located in the nearby post office. Shooting their way past the guards at the door, the Americans burst inside the building, destroyed what they believed to be the detonation equipment, and then found themselves cut off and unable to return to the traffic circle. With the help of resistance fighters, Adams and his men held off the Germans until they were rescued three days later. The next morning at 7:45, Company G, 3rd Battalion, 508th was called from atop Hill 64, about a mile from the southern end of the bridge. Renewing the effort to take the span, Captain Frank Novak led his men through back streets on the edge of Nijmegen, somewhat shielded from the Germans. The troopers were greeted by smiling townspeople, who threw flowers and fruit to them. However, as the Americans got closer to the bridge the adoring throng dissipated. The Germans had worked through the night to strengthen their positions around the traffic circle and waited. When the Americans approached, they opened with rifles, machine guns, 20mm flak cannons, and 88mm artillery. Novak sent his men through the withering fire, and the troopers advanced to within a block of the traffic circle before they were stopped. Reinforcements could not be sent without weakening the defenses along the ridgeline or jeopardizing the security of the glider landing zones, where planes were expected at any time. At 2 pm, Company G was pulled out of its hard-won position and returned to Hill 64. While the Nijmegen highway bridge was firmly in German hands, at least for the time being, the gliders began to slide into their landing zones. The perimeters were thinly held, and German soldiers infiltrated from the Reichswald under cover of darkness, leading to pitched battles. During one of these, a company of the 508th PIR was surrounded temporarily, and stiff resistance delayed the 505th in clearing one zone of enemy troops. Colonel Lindquist sent a company of the 508th to sweep the northern landing zone, and the eight-mile forced march from Nijmegen took the breath away from many of the already exhausted troopers. Nevertheless, they mounted a Hollywood-style downhill charge into the teeth of German small arms fire and flak guns depressed to discharge as antipersonnel weapons. When the battle reached a crescendo, the Germans finally broke and ran. Just as gliders began touching down, the paratroopers chased the last enemy soldiers away. They killed 50 Germans and captured 150 more at the cost of 11 casualties. Bad weather forced the postponement of the insertion of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment set for the 19th. American paratroopers along the corridor to Nijmegen consolidated defensive positions and held against German attacks here and there. Contradictory reports of enemy tanks in the Reichswald filtered through command posts. General Browning approved a plan to capture the bridge in a night assault on September 18 but then decided that holding the high ground to await the arrival of XXX Corps was the best tactic. Gavin cancelled the plan. Within hours of crossing the Wilhelmina Canal at Son, the vanguard of XXX Corps reached Nijmegen. A flicker of hope remained that the ground forces might reach Frost’s men at Arnhem. After securing the large bridge at Nijmegen, American troopers of the 82nd Airborne Division guard wounded German prisoners. When their initial attempt to seize the bridge was delayed, the American paratroopers were obliged to fight against the German II SS Panzer Corps in the streets of the city. On the afternoon of September 19, Gavin conferred with General Sir Brian Horrocks, commander of XXX Corps, and described a plan that he believed offered the best opportunity to seize the highway bridge. “There’s only one way to take this bridge,” he had already briefed his staff. “We’ve got to get it simultaneously from both ends.” Gavin intended to send paratroopers across the Waal in small boats downstream from the highway bridge and a nearby railroad bridge that had been a secondary objective. Once on the northern bank of the river, these troopers would outflank the defenders of both bridges, forcing them to withdraw. While the amphibious assault was underway, the defenders at the southern ends of both bridges were to be hit hard by combined elements of XXX Corps and the 82nd Airborne. The plan was fraught with risk, but while Gavin thought of his own men and the casualties they would likely absorb he also considered the plight of the beleaguered 1st Airborne at Arnhem. It was imperative for XXX Corps to cross the Waal. At the same time, Gavin had been forced to divert troops from other sectors to Nijmegen, and prolonged fighting had reduced his strength along the ridgeline significantly. Two days into Market Garden, Company A, 505th PIR was down to two officers and 42 men. While the amphibious operation was discussed, efforts to breach the German defenses at the bridges continued. On the afternoon of September 19, the 2nd Battalion, 505th PIR, under Lt. Col. B.H. Vandervoort, supported by a British infantry company and a battalion of Guards Armoured Division tanks, attacked the southern end of the railroad bridge. Some American paratroopers hitched rides atop the British tanks, and the direct assault was underway at 3 pm. Company D, 505th, commanded by Lieutenant Oliver B. Carr, began taking fire from the railroad marshaling yards about 1,000 yards from the southern end of the bridge. Covered by supporting fire from the tanks and the artillery of the 82nd Airborne and Guards Armoured Divisions, Carr’s men cut the distance to their objective in half but came under a hail of fire from enemy guns between the bridge and the railroad station. A shell from a German 88 slammed into the lead British tank and disabled it. Repeated efforts to renew the advance were fruitless. At the same time, paratroopers, British infantry, and tanks hit the southern end of the highway bridge. When the attackers closed to within 300 yards of the traffic circle, they split left and right into two groups. Simultaneously, German crossfire from the traffic circle and the streets that emptied into it began blazing away. On the left, Company F, 505th PIR inched ahead, but its supporting tanks were stopped cold by a log barricade. On the right, the British troops, Company E, 505th, and the rest of the armor advanced within 100 yards of the traffic circle before an antitank gun destroyed the lead British tank and three more were crippled in rapid succession. The assault stalled. Further attempts during the long afternoon were also repulsed. For the fourth time, the Allies had been denied the highway bridge over the Waal. The Germans held firm at the railroad bridge as well. It seemed that mere yards might as well have been miles. As twilight shrouded the scene, the firing dissipated. On the night of the 19th, Gavin ordered Colonel Tucker to detach two companies to defend the bridges over the Maas and Maas-Waal Canal. The remainder of the 504th PIR received orders to make the hazardous amphibious crossing at Nijmegen. The Americans failed to scrounge enough boats to make the assault, but the British offered a solution. Thirty-three canvas boats from the XXX Corps engineers could be brought up by mid-day on the 20th. Originally set for 1 PM, the attack was postponed for two hours when the boats were delayed in traffic. While the area the amphibious assault would launch from along the southern bank of the Waal was cleared of Germans and the attack on the southern end of the highway bridge was renewed, strong German counterattacks from the Reichswald threatened the plans at Nijmegen. Although the 1st Battalion, 505th gave ground around the villages of Riethorst and Mook, Major Talton W. Long committed two platoons of infantry, his only reserve, and tanks from the Coldstream Guards of XXX Corps rumbled up to bolster new defensive positions. When the Germans had finally been thrown back, Long’s battalion counted 20 killed, 54 wounded, and seven men missing. To the north, two platoons of the 508th PIR were forced out of the village of Wyler, and troopers were pushed back near the town of Beek toward the Berg en Dal. The Germans missed an opportunity to slip around the Allied right flank and reach the outskirts of Nijmegen unmolested. The 508th fought throughout the next day to regain the lost ground. As 3 pm on September 20, 1944, approached, Major Julian Cook and the 3rd Battalion, 504th PIR, prepared for one of the epic assaults of World War II. The flimsy canvas and plywood boats that would carry them from the vicinity of a power plant on the southern bank across the 400-yard breadth of the Waal River about a mile north of the railroad bridge were assembled. They reached the paratroopers only 20 minutes before the attack was to step off. American paratroopers rush through the dirt and debris raised by the explosion of German 88mm shells following Operation Market Garden. When the initial effort to seize the bridge at Arnhem across the Lower Rhine failed, the American airborne troops remained in the Netherlands to support ground efforts, assaulting Arnhem in October 1944. The boats were 19 feet long, and when they arrived the men counted 26 of them rather than 33. To deliver all the troopers slated for the first wave to cross the Waal these puny craft would be dangerously overloaded. The three engineers who rode in each boat were ordered to paddle back across the river for another load when the first men had reached the far side. To support the crossing that was intended to outflank the Germans on the northern bank of the river and oblige them to withdraw from the bridges, a detail from another battalion of the 504th would join in the crossing while rocket-firing Hawker Typhoon fighter bombers would roar in to soften up the German positions. About 100 artillery pieces would fire a 15-minute preparatory barrage and lay a smokescreen to obscure the vision of the German gunners watching the paratroopers paddle across the choppy river like sitting ducks. To effect the crossing in the face of heavy German small arms and artillery fire, the paratroopers would also have to contend with the swift current of the Waal, running eight to 10 miles per hour in some locations. The surrounding terrain was flat and open, and though Gavin had intended for the boats to load in a secluded area near the mouth of the Maas-Waal Canal, the current was so swift that it was necessary to load in the open. The barrels of German guns pointed at the men while observers among the tall steel girders of the railroad bridge watched their every move. Seconds after the Allied artillery switched from high-explosive to white phosphorous shells, the wind began to sweep the shroud of smoke away. Little cover was provided. Carrying the assault boats on their shoulders, the paratroopers stepped into the shallow water at the edge of the Waal. Some slipped along the muddy bank and fell into the current. Others were mired in the muck of the bottom. Machine-gun bullets zipped into the water, tearing the canvas sides of the boats while 20mm guns at the railroad bridge barked. Several boats were shredded. One was hit by mortar fire and capsized just 20 yards from the northern bank. Private Joseph Jedlicka went straight to the bottom of the Waal in eight feet of water but managed to maintain his wits, hold his breath and his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), and walk to the shoreline where the scene was reminiscent of Dante’s Inferno with smoke, fire, blood, and death everywhere. Lieutenant Colonel J.O.E. “Joe” Vandeleur, commander of the 3rd Battalion, Irish Guards, was captivated as the drama unfolded. “It was a horrible, horrible sight,” he later wrote. “Boats were literally blown out of the water. Huge geysers shot up as shells hit and small arms fire from the northern bank made the river look like a seething cauldron. I remember almost trying to will the Americans to go faster.” Major Cook, a devout Catholic, was in the first wave, paddling and loudly reciting the Hail Mary amid the storm of enemy fire. Half the boats were lost, but the engineers turned the remaining 13 back for another load. Eleven of them managed to run the gauntlet. The heroic engineers aboard these boats made six trips during the long afternoon, delivering the balance of the 3rd Battalion and then the 1st Battalion, 504th to the northern bank. Those who survived the harrowing crossing set to work in small groups. Unit cohesion was nonexistent. Leaving more than 50 Germans dead along the riverbank, the first paratroopers sprinted across an open field to a roadbed lined with dikes about 800 yards from the Waal. They threw hand grenades and in hand-to-hand combat cleared the Germans out with bayonets. Although they had become jumbled during the crossing, the paratroopers maintained the initiative, men following officers of different companies but working as teams to silence machine-gun positions and scatter defenders. The paratroopers came upon the German strongpoint at Fort Hof van Holland, which they had been ordered to bypass. Instead, they seized an opportunity to take it. Sergeant Leroy Richmond of Company H swam underwater across a moat surrounding the fort and motioned to his comrades to follow across a causeway. They rushed forward, taking out the machine guns and 20mm flak cannons firing at the Americans from the fort’s towers. While the attack pressed ahead, the Germans apparently never attempted to blow up either the railroad or the highway bridge. Men of Companies H and I reached the northern ends of both spans and loosed automatic weapons fire across them. Finally, around 4:20 pm, the Germans at the traffic circle began to crack. Troopers of the 505th PIR and British tanks hammered their way through the streets and into the enemy perimeter to claim the southern end of the highway bridge. British tankers saw an American flag flying across the river and believed it was the signal to cross the highway bridge to the northern bank. The flag was actually at the railroad bridge. The Americans on the other side were still some distance from the highway bridge. Nevertheless, four tanks started across the Waal, guns blazing, and three of them reached the other side. At 7:10 pm, three privates of Companies H and I reached the northern end of the highway bridge to link up with the British tanks. The fight was over. At the railroad bridge, Germans streamed back toward the northern bank of the Waal and became trapped on the span as Allied troops sprayed them with rifle and machine-gun fire. A total of 267 Germans were killed on the railroad bridge, and dozens of prisoners were captured. Cook’s 3rd Battalion paid a high price for the success with 28 dead, 78 wounded, and one man missing. In the extended fight at the traffic circle, the 505th had lost about 200 men. During Market Garden, the 82nd Airborne suffered 1,432 casualties. Major Cook survived the ordeal and later received the Distinguished Service Cross. General Horrocks mused that the 3rd Battalion’s combat transit of the Waal was “the most gallant attack ever carried out” in World War II. Allied commanders were puzzled as to why the Germans had not blown the key bridges. Courage and good fortune had, at long last, won the day. Colonel Reuben Tucker was justifiably proud of his command, which had finally kicked open the door to Arnhem. However, as some XXX Corps tanks helped hold the lodgment on the northern bank of the Waal, the large armored column halted in and around Nijmegen. Running low on fuel and ammunition, the tankers were exhausted. Their infantry support, critical to the armored advance along the narrow, elevated road to Arnhem, had not come up yet, and daylight was ebbing away. Tucker was dumbfounded. “We had killed ourselves crossing the Waal to grab the north end of the bridge. We just stood there seething, as the British settled in for the night, failing to take advantage of the situation. We couldn’t understand it. It simply wasn’t the way we did things in the American Army—especially if it had been our men hanging by their fingernails 11 miles away.” Frost’s battalion lost its hold on the northern end of the Arnhem bridge across the Lower Rhine on September 21 and was driven back into the town. The Germans controlled the span and used it to move tanks, artillery, and SS troops to block the advance of XXX Corps toward Arnhem. The first effort to reach the trapped British paras progressed four miles but could go no farther. An airdrop of the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade was unable to establish a link with the bulk of the 1st Airborne at Oosterbeek and was under constant pressure from German artillery and infantry probes. By the afternoon of September 20, Frost’s contingent in Arnhem had ceased to exist as a fighting force. On September 25, the remnants of the 1st Airborne Division began filtering back from the northern bank of the Lower Rhine. Although Market Garden had ended in disappointment, some gains were achieved. The northern flank of the Allied armies was extended 65 miles across two canals and the Maas and Waal Rivers, while a considerable amount of Dutch territory had been liberated. Although the two U.S. airborne divisions that had participated in Operation Market Garden were to have been released as soon as possible after their missions were accomplished, the 82nd Airborne, like the 101st, remained in the line for days. Its troopers successfully defended against attempts by the German II Parachute Corps to take the hills and ridges around Groesbeek, and elements of the division joined the 101st on the Island. Senior commanders argued for the release of the airborne divisions, particularly since additional operations were planned near the end of the year, but the acute shortage of British manpower required that the Americans remain in the combat zone. Finally, on November 11, a full 55 days after their Market Garden jump, the 82nd Airborne began pulling out of the line. In addition to its casualties in Market Garden, the division lost 1,912 men while defending the highway corridor, the high ground, and the Island. As the paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st were trucked down the roads they had fought to hold for nearly two months, Dutch civilians lined the streets in the towns and villages. Many of them shouted, “September 17!” To this day, they remember the heroism of all the Allied troops who sacrificed for their freedom and the bridges northward into the Netherlands. Michael E. Haskew is the editor of WWII History. He has written numerous books and articles on various aspects of military history and resides in Chattanooga, Tennessee.](https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/M-Arnhem-8-Oct01.jpg)

Bittrich, a sharp tactician, sensed the situation and was already responding with great insight. He ordered the tanks of the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions to Arnhem and Nijmegen, respectively. German troops cut the roads eastward to Arnhem and blocked the advance of the 1st Airborne toward the city.

Only the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade, 500 men under Lt. Col. John D. Frost, reached the northern end of the main bridge across the Lower Rhine at Arnhem. These paras were set upon by superior German forces but held on grimly, waiting in vain for the arrival of the remainder of the 1st Airborne Division, which was stymied on the roads.

Due to the stiff resistance west of Arnhem, Operation Market Garden was doomed to fail. The 1st Airborne Division fought gallantly for 10 days, but of the nearly 10,000 paratroopers Urquhart had taken into the vicinity of Arnhem just over 2,000 evaded death or capture. Frost’s valiant command held out at the Arnhem highway bridge for nearly four days before surrendering. Fewer than 50 men of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Brigade managed to escape.

Only two battalions of the 101st Airborne Division failed to land in or near their drop zones on September 17. Dropping near Son, the 506th PIR, under Colonel Robert Sink, was to capture a bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal and continue south to Eindhoven. The 502nd PIR, commanded by Colonel John H. Michaelis, was to establish a perimeter around its drop zone north of the 506th for later use as a glider-landing zone. Then, it was to capture more bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal near the town of Best and one of those spanning the Dommel. Farther north, Colonel Howard Johnson’s 501st was to capture four road and rail bridges on the Willems Canal and the Aa River near Veghel.

The 501st PIR made rapid progress. Lt. Col. Harry W.O. Kinnard, commanding the 1st Battalion, one of the two that had dropped in the wrong place, set off toward Veghel as some of the troopers commandeered bicycles and trucks to speed the advance. When Kinnard reached Veghel a handful of his men had already secured the railroad bridge over the Aa. The 2nd Battalion seized three bridges at Veghel, while the 3rd Battalion took the town of Eerde and cut the Veghel-St. Oedenrode highway, covering the regiment’s rear.

The 501st secured all of its September 17 objectives in about three hours, capturing scores of prisoners. In his haste to move against Veghel, though, Kinnard had not taken all his battalion’s equipment along. He left 46 men under Captain W.S. Burd to bring the equipment and several paratroopers who had been injured during the jump forward at a slower pace. Burd’s detachment was attacked by a strong German force and pushed back to a single building. When word of Burd’s plight reached Kinnard, Colonel Johnson allowed him to send a platoon to the rescue. The attempt failed, and the survivors of Burd’s group were captured.

The other battalion of the 101st dropped outside its zone was the 1st of the 502nd led by Lt. Col. Patrick Cassidy. Cassidy’s men nevertheless swept into St. Oedenrode, commanding a major highway and a bridge across the Dommel. They occupied the town, killed 20 Germans, and took another 58 prisoner.

General Taylor, commanding the 101st, recognized the importance of the rail and highway bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal near Best. Although they were not on the direct XXX Corps line of advance, Taylor considered them vital in strengthening his defensive perimeter and knew that they could be used if the route through Son was blocked.

Captain Robert E. Jones of Company H, 502nd PIR, started toward these bridges and immediately took heavy German fire. Jones sent a patrol under Lieutenant Edward L. Wierzbowski forward. The Americans came within sight of the highway bridge but were forced to dig in, their strength reduced to three officers and 15 men.

Commanding the 3rd Battalion, 502nd, Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole, who had earned the Medal of Honor in Normandy, started out with the rest of his battalion to find Jones and Company H at about 6 PM, but the effort was halted by darkness. The next morning, Cole spoke over his radio to a pilot flying nearby. The pilot asked for orange recognition panels to be placed on the ground near the battalion command post, and the officer decided to handle the chore himself. Cole raised his head slightly, shielding his eyes against the sun and looking overhead for the plane. A single shot rang out. Cole fell dead from a sniper’s bullet fired from a farmhouse 300 yards away.

The capture of Best ultimately required two more days and a much larger force, including British tanks and two more battalions of troops. Pfc. Class Joe E. Mann was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for heroism during the fight for Best. Like Cole, he was killed by a German sniper.

South of Son, General Taylor accompanied the 1st Battalion, 506th toward the Wilhelmina Canal road bridge. Just south of the town near the edge of the Zonsche Forest, German 88mm guns opened up on the paratroopers. More 88s zeroed in on the other two battalions of the 506th, led by Colonel Sink.

Paratrooper Don Burgett of the 1st Battalion recalled the vicious battle for Son. “We organized and we began to charge the guns,” he related. “The only way we were going to survive was to knock out the 88s even though a lot of us were going to die trying to do it. As we were running toward them, they fired at us at point-blank range. We overran their positions. There were several 88s. They were sandbagged and dug in and used for antiaircraft. A trooper from D Company got in close enough and fired a bazooka and knocked out one of the guns.”

Both groups of the 506th advanced toward the bridge. “We overran the 88s, took the German gunners prisoner, and someone said, ‘Let’s take the bridge,’” Burgett continued. “We started to run toward the bridge. We were within yards of the bridge when the Germans blew it up. It went off with quite a force…. We hit the ground. I rolled over on my back because everything got real quiet, and I saw the debris in the air. I remember seeing this tiny straw that was turning slowly way up in the air and as it hit its maximum trajectory and it started to come down, it became larger and larger. About halfway down we realized the size of this thing. It was probably about two feet wide and forty feet long. There was no place to run. When it hit the ground, the ground shook like Jell-O.”

With the Son bridge blown to pieces, the capture of Eindhoven was slowed. However, XXX Corps halted that evening at Valkenswaard, six miles away. Unexpectedly heavy German resistance had upset the timetable for Garden, the critical ground phase of the offensive. The narrow road was elevated above the surrounding fields, and British tanks were silhouetted against the sun, perfect targets for German antitank weapons. Each time a machine-gun nest erupted, the narrow British column was required to halt and deploy infantry to remove the threat.

By the time XXX Corps got to Eindhoven the next day, the town belonged to the 101st Airborne Division. At nightfall on the 17th, the 101st was in control of Veghel, St. Oedenrode, and Son. Although the 502nd had encountered tough German troops around Best, the objective there was secondary. With a few more hours of hard fighting, the 101st would have its stretch of Hell’s Highway completely open.

As soon as they saw the first Allied soldiers, jubilant Dutch civilians had welcomed them as liberators. Early on the morning of September 18, the 506th destroyed a pair of German 88s and pushed into Eindhoven. While throngs of citizens celebrated their apparent liberation in the streets, the paratroopers disarmed a handful of Germans. One American officer recalled, “The reception was terrific. The air seemed to reek with hate for the Germans….”

Finally, at 5 pm on the 18th, the leading elements of XXX Corps rumbled through Eindhoven virtually without stopping. At Son, Canadian engineers, who had been notified that the existing bridge had been destroyed, worked through the night to deploy a prefabricated Bailey bridge. At 6:45 am on the 19th, the tanks of XXX Corps rumbled across the Wilhelmina Canal, but they were 33 critical hours behind schedule.

Later on the morning of September 19, XXX Corps was across the Willems Canal and the Aa River at Veghel, moving into the zone of the 82nd Airborne. In the 101st sector, the primary job became holding the narrow corridor of hope open against German counterattacks. While Allied armor was advancing northward, it was imperative to keep the road open to facilitate the flow of troops and supplies.

The Germans fought back viciously against 101st defensive positions around Eindhoven, Son, St. Oedenrode, and Veghel. General Taylor likened the actions to the bushwhacking style of Indian fighting in the Old West. The Germans attacked repeatedly, cutting the narrow road. They were driven away each time.

On the 22nd, the Germans mounted a counterattack against Veghel supported by heavy artillery and aircraft. The attack was not completely beaten back for two days. “It was a very depressing atmosphere listening to the civilians moan, shriek, sing hymns and say their prayers,” wrote Daniel Kenyon Webster of E Company, 506th PIR, remembering the steady concussions of artillery shells hammering the town.

Webster and Private Don Wiseman hunkered deeply into a foxhole. “Wiseman and I sat in our corners and cursed,” Webster offered. “Every time we heard a shell come over, we closed our eyes and put our heads between our legs. Every time the shells went off, we looked up and grinned at each other.”

On September 24, the Germans shot up a British column on Hell’s Highway at Koevering northeast of Eindhoven. Burgett remembered, “Germans brought up some 40mm cannons and they had some self-propelled guns and they shot the British who were lined up on the side of the road and they were brewing tea in these five-gallon tins and the Germans just opened up on them. They killed over 300.