By William Dennis

By the summer of 1943, American forces felt that they had proven that they were as good as anything the enemy could throw at them. The British, however, still had their doubts. After all, the British had been fighting Hitler’s and Mussolini’s armies for three years—virtually alone. The initial poor showing by green American troops in North Africa had convinced many in the King’s army that Roosevelt’s boys were undertrained, poorly motivated, and just plain inept.

Consequently, the British planners of Operation Husky had relegated the Americans to a largely supporting role. On Sicily, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. was determined to show that the American fighting man was as good or better than any army—friend or foe.

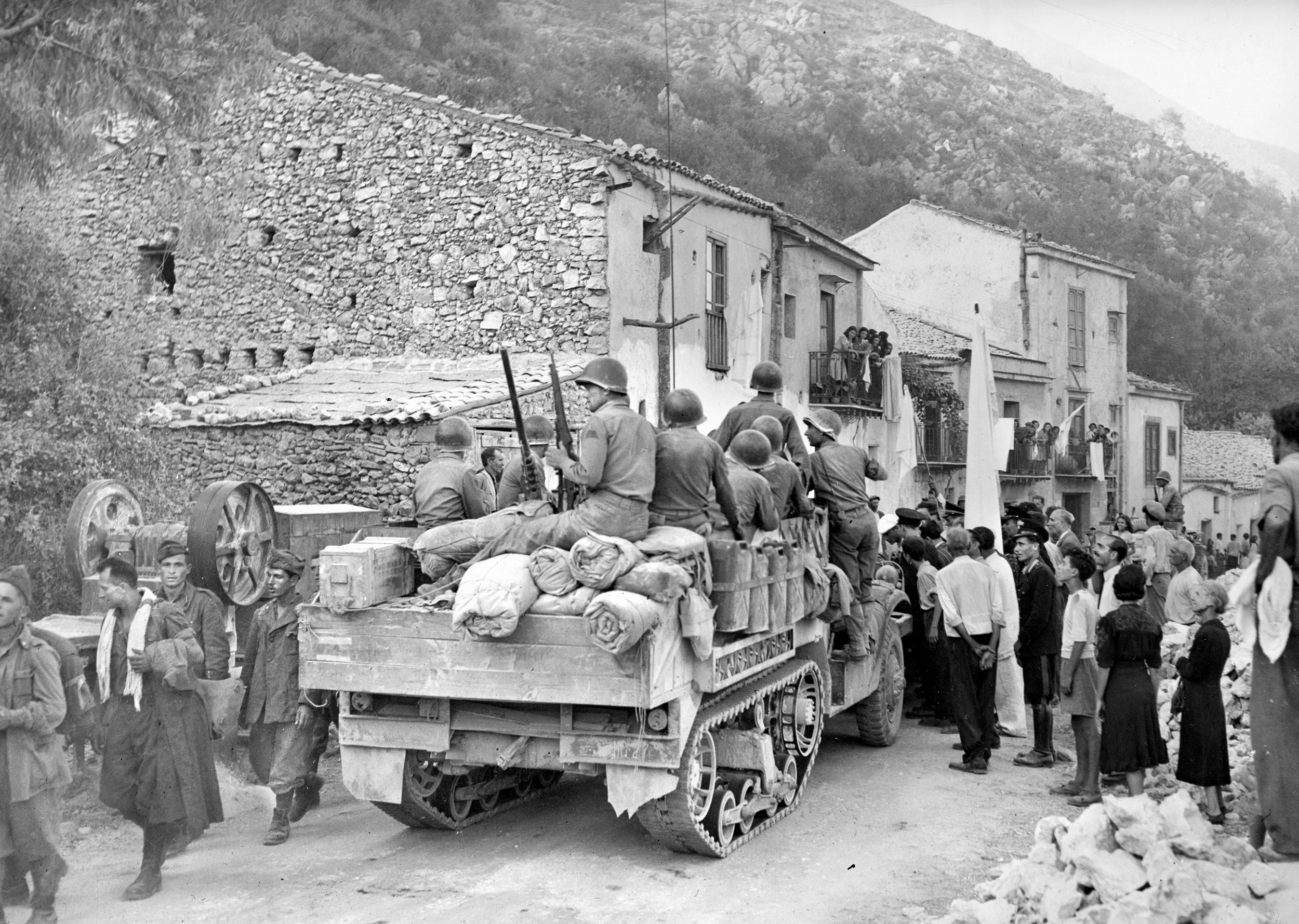

On July 10, 1943, Patton’s U.S. Seventh Army assaulted the coastline of the south-eastern point of Sicily. Simultaneously, the British Eighth Army under General Bernard Law Montgomery landed on the eastern side of the point. Previously, Allied offensives had turned back the Axis attempt to conquer Egypt and cleared the Axis out of Africa. This would be the first time the Western Allies had initiated a major move against an Axis homeland.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill once quipped that Britain and America were two peoples divided by a common language, but it went far beyond that. Differences in equipment and tactical doctrine, plus the attitudes and personalities of the commanding generals, had major impacts on the campaign. For the Allies to effectively confront the Axis, Britain and America had to work through these problems.

Kasserine Pass in Tunisia was the first heavy combat the U.S. Army faced against the Axis in World War II. The troops had arrived in Africa half-trained and had been clumsily handled. It had not gone well. Combat leadership and discipline needed strengthening. Better training in patrolling, reconnaissance, and combined-arms coordination were also needed.

Until a few months before, little had gone well for the British Army, either, but that did not keep the British from being so negative about the American Army that even Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower complained.

British generals, including Sir Harold Alexander and Bernard Law Montgomery, did not hide their disrespect. Lietenant General Kenneth Anderson’s British First Army in Tunisia had included an American corps.

Toward the end of that campaign, he questioned Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon, the commander of the U.S. 1st Armored Division about how he planned to employ his troops in the rugged terrain of Northern Tunisia.

After the briefing, Anderson shook his head and twice muttered, “just a childish fantasy” as he stalked away. By that time, the U.S. Army leaders in North Africa were having success in improving their units’ performance. But somehow the British generals remained unaware of it.

They also seemed unaware that differences in equipment and tactical doctrine meant the Americans could move much faster than British. Still, Alexander and Montgomery intended for the Eighth Army in Sicily to defeat Axis troops while the Americans merely covered their flank.

At the northeastern tip of the island, close to the Italian mainland, the city of Messina is overshadowed by Mt. Etna and can only be approached via a narrow route along the island’s south coast or through rugged mountains north of the volcano. There is little cover for advancing troops. Dusty roads, open fields and observation points on high mountains made even a modest force of artillery highly effective. The typical Sicilian town is located on a defensible ridge top. The island is disease-ridden, hot, dry, and paradoxically humid.

In the summer of 1943, Sicily was defended by between 300,000 and 350,000 German and Italian troops. Some Italian units were mobile but most of them were assigned to coastal defense units. The Italian Sixth Army commanded more than 200,000 of these troops. The number was misleading as they were poorly armed, equipped, and led. Moreover, they were sick of fascism and the war it had lead them into.

Initially, they were “assisted” by two German divisions. The 15th PzG (Panzergrenadier) Division was still forming, but it could fight effectively. It was in reserve with one regiment deployed in the western half of the island with the divisional headquarters. One regiment was in the center of Sicily attached to the Sixth Army, and another in the east, attached to the Luftwaffe’s Herman Göring Panzer (HGPz) Division.

For most of the war, Luftwaffe parachute divisions were exceptionally motivated, well-trained and equipped. The Luftwaffe infantry and panzer divisions were not.

The HGPz was originally Göring’s largely ceremonial guard regiment expanded to division strength; most of it had been destroyed in Tunisia. It was being reconstituted, or as one historian put it, “cobbled together” primarily with men the Luftwaffe could spare from other duties.

Typically, they had little training or experience in ground fighting. Nor, according to its chief of staff, was most of the leadership up to handling their jobs. The only exceptions were its artillery batteries, which were well-trained and experienced.

Shortages meant Germany made extensive use of captured equipment—and even that was increasingly scarce. It was bizarre to lavish first-rate equipment on an inexperienced, partly trained and poorly led unit. As an “elite” unit, the only company of Tiger tanks on the island was transferred to the HGPz from 15th PzG.

The division’s problems were compounded by moving its headquarters and about two thirds of its strength to the Caltagirone area near Gela, on the southern shore, shortly before the invasion. The remainder, with the attached panzergrenadier regiment, was near Catania, under Colonel Wilhelm Schmalz.

Before the campaign was over, the Germans would bring in the 29th PzG and 1st Parachute Divisions.

By the time of the invasion, the Italian Air Force was a shadow of its former strength.

The Luftwaffe’s presence in Sicily had been reduced to a handful of badly worn Messerschmitt Me bf 109s, flown by exhausted pilots; Focke-Wulf and bomber squadrons had been withdrawn to Sardinia. Axis naval activity was confined to supplying and later evacuating the island. American Major General Carl Spaatz commanded the Northwest African Air Force, formed to support the invasion. Maj. Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle commanded bomber units, and Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Coningham commanded the tactical air units.

The Allies had more and better airplanes and better-trained pilots, but many fighters had only short-range capability; flying from Malta and Tunisia, they had little flight time left over Sicily. Therefore, it was imperative that the Allies promptly capture airfields there.

The transport units were not well trained in night formation flying. Another problem was Allied ground support doctrine emphasized wide ranging sweeps seeking enemy columns and supply convoys. That meant there were few aircraft available to provide direct support to troops actually in contact during fast-moving battles.

The U.S. Army and Navy found the Army Air Force uncooperative, ignoring requests for aerial photographs of the American landing beaches until Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, appealed directly to General Spaatz.

Historian Carlo D’Este sees the root of that uncooperation as their commander’s desire to maintain the air services’ independence and their almost hubristic insistence that airpower alone could win the war in Europe, probably without an invasion of the continent. Allied naval units were strong enough to move a large force to the island with surprisingly little loss and to support the initial landing with very effective gunfire.

The British Eighth Army contained two corps. After landing, Lt. Gen. Sir Oliver Leese’s XXX Corps, with the 1st Canadian Division, 51st (Highland) Division, and the independent 231st Infantry Brigade, would move northwesterly to make contact with Patton’s forces near Ragusa. Oddly, the Canadians would sail directly from chilly Scotland into Sicily’s heat and humidity.

Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey’s XIII Corps, with 5th and 50th Divisions, would land further east in the Gulf of Noto. It was assigned an ambitious set of objectives, beginning with the capture of Syracusa and the coastal area, including the Catania plain, up to the flanks of Mount Etna. The army’s reserve—the British 78th Division and the 1st Canadian Tank Brigade—remained in Tunisia for the time being.

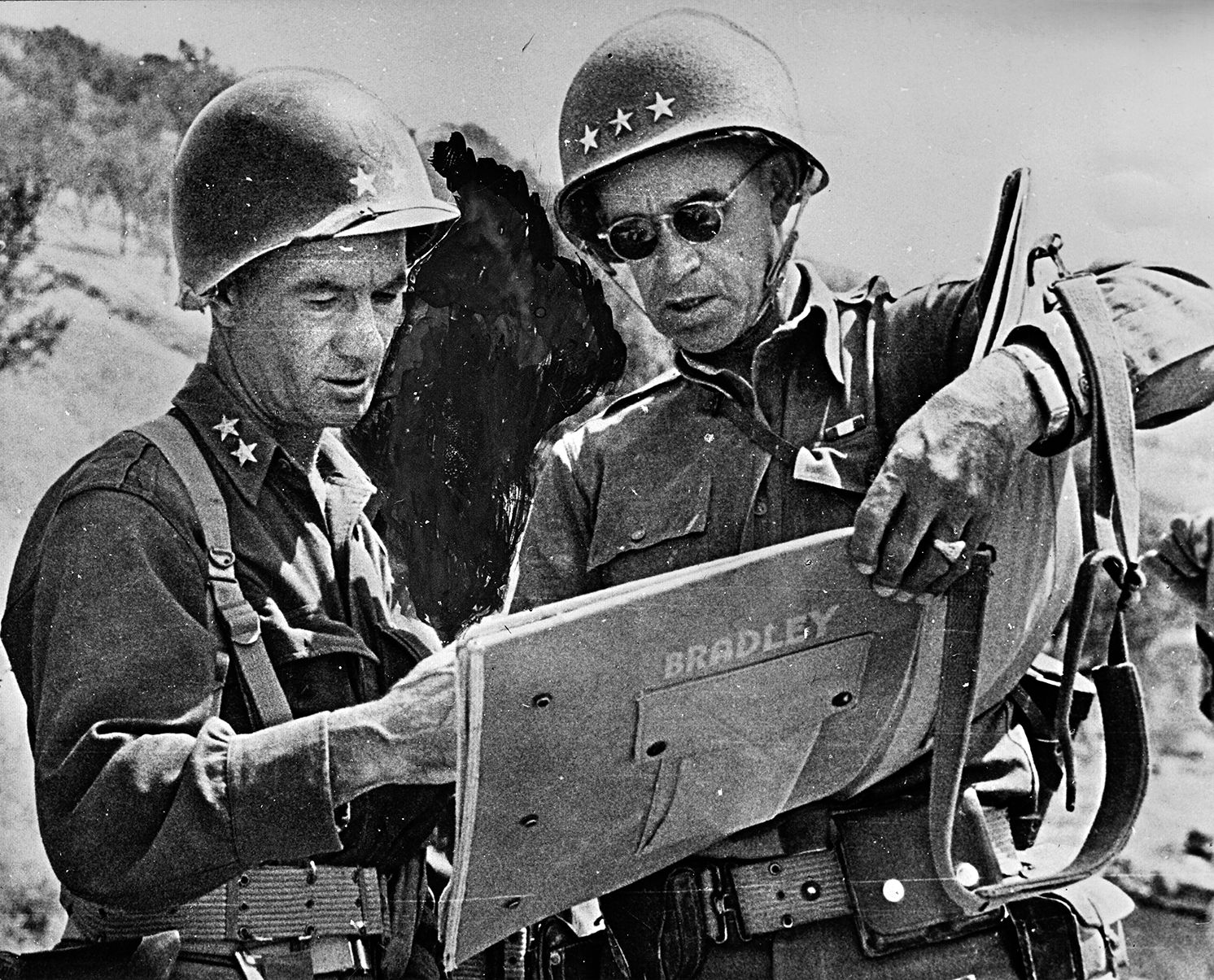

Patton’s Seventh Army landed in the Gulf of Gela, from Licata to Pozzallo, to capture nearby airfields. Maj. Gen. Omar Bradley’s II Corps would land its 1st Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Terry de la Mesa Allen, on beaches east of Gela. “X Force,” built around the 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions, a battalion of combat engineers, three chemical mortar companies, and an engineer shore battalion would assault the city itself.

Major General Troy Middleton’s 45th Infantry Division would land at Scoglitti on the right flank of the landing area. The separate “Joss Force”—Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division, plus the 3rd Ranger Battalion, would land near Licata and anchor the left flank.

Gela was the most crucial and the most vulnerable of all the landing spots. The key to its success was controlling high ground about five miles inland. Highway 117 runs north from Gela, crosses the ridge between two hills, and continues on toward Nisceme, Enna, and the north coast. Roads from Caltagirone and Vitoria fed into this road. Axis troops moving south to counterattack would surely use it.

A well-built strongpoint—the “Piano Lupo”—controlled traffic along these roads; Colonel James Gavin’s 505th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd Airborne Division, with an attached battalion, were to land inland from Gela and capture the ridge. Allen’s 1st Infantry was to advance as quickly as possible and relieve them.

Further south, about four miles from the beach, was more high ground overlooking the Biscari road and the Biscari-Gela road junction. Americans called it the Biazza Ridge. Paratroops would also land there.

The 9th Infantry Division remained in Army reserve in North Africa. Its 39th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) and the rest of the division artillery were ready to go wherever they were needed. The remainder of the 82nd was available to drop onto the island.

The Mediterranean Theater commander, Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, played only a limited role in the campaign because the British had persuaded the Allies to adopt their traditional command setup, which here was a committee made up of the theater commander, the army group commander, and the two army commanders. If the army and army group commanders were in agreement, the theater commander could do little to override their decisions. In spite of Ike’s skill with “persuasion and hints,” this arrangement worked poorly.

The army group commander, General the Honorable Sir Harold Alexander, was well regarded for “his easy smiling grace and contagious confidence.” In World War I, he received multiple, well-deserved decorations for valor. But one British officer who worked closely with him wrote that he had never had an original idea in all the time he had known him. He had two other major failings: “His consistent failure to grasp the reigns of higher command” and, in spite of their successes, he never lost “his complete lack of faith in the American soldier.”

In the latter part of the Italian campaign, when the American Army was clearly carrying the exhausted Eighth Army, Alexander disparaged the level of training in the American Army to visiting General George C. Marshall, who responded that, while American troops made beginner’s mistakes, they quickly learned from them.

Initially, Montgomery shared Alexander’s dim view of the American Army. But once he saw its impressive flexibility and mobility, he realized that these virtues were not fully shared by the British Army.

Montgomery’s personality was somewhat different from his portrayal in the 1970 movie Patton. His papers showed he had no interest in racing Patton to Messina.

He was preoccupied with the military profession and made a lifelong study of it. But he was an extremely difficult person who infuriated people all his life. He was simply unable to see anyone else’s point of view or appreciate the impact his incessant arguing, even nagging, had on his personal relations.

Montgomery has been criticized for wanting every little detail in place before making even a short, set-piece attack. Also, his army’s vigorous and incautious advance during the first days of the campaign spread the limited strength he had ashore too widely.

Granted, El Alamein was a set-piece attack that did not start until Montgomery was completely ready, as were many of his later attacks in Tunisia and Normandy. But set-piece, limited-objective attacks were the forte of the army he had to work with.

By way of contrast, Germans found the American Army to be “extraordinarily flexible; they adapted immediately to a changed situation.” That was following a tradition of moving quickly to take advantage of an enemy that is unready or off balance. It goes back at least as far as Washington’s quick move against Princeton before the British were fully aware of his success at Trenton.

In World War II, this was facilitated by mobility that was superior to every other army.

The British lacked rugged two-and-a-half-ton trucks and capable artillery-pulling tractors.

Eisenhower would later have to assign a number of American truck companies to the British to allow them to advance from Normandy to the new front on the German border rapidly enough to keep pace with the Americans.

Patton was more complex. He deserves much of the credit for the American Army’s improvements in Tunisia, and he was arguably the best U.S. fighting general in the war.

A brilliant intellectual fluent in French, with a grounding in French culture, he could be quite charming, but he felt that he would be more effective if he came across as hard and fierce, so he developed a façade—“his war face”—to project those characteristics.

Admittedly, Patton sometimes sought the limelight. His despicable conduct toward soldiers in hospitals who he thought were cowards and shirkers is well known. But on another occasion, he was found crying in a latrine after visiting an amputee ward.

Once the British landing was secure, the plan was for them to move on to the Catania plain, which contained a number of airfields. It had looked like good tank country on maps and aerial photographs, but the terrain turned out to be filled with rock walls and ditches and studded with farm houses, usually in groves of trees, that were natural sites for anti-tank guns. It was a bad place for gliders and armor alike.

The Arapo River that lay between the landing beaches and the plain was a significant barrier unless the Ponte Grande bridge over it was captured intact. The British allotted a full brigade of glider troops—over 2,000 men—to the mission. The force took off for Sicily in 100 gliders but only 12 reached the designated landing zone.

That handful of men, and a few more, held the bridge against a mixed group of Italian servicemen until midafternoon when the last few, mostly wounded, glidermen surrendered.

Troops advancing from the beach recaptured the bridge half an hour later.

That was virtually the only Axis success in the British sector for the first several days.

Many Italian troops quickly surrendered and the only German unit initially facing the British, Team Schmalz, was far too weak to do more than slow the British advance.

If the landings in the British sector were “anticlimactic,” there was much confusion on the American beaches, and the paratroopers were widely scattered. Still, by early morning, it was clear that both landings were succeeding, albeit slowly.

Facing larger, better-trained-and-equipped Allied ground forces, the Axis’ only hope was to smash the landings during the first hours when the invasion was most vulnerable. They focused their D-day counterattack on the Gela landing. Mobile Italian forces were to make the initial counterattack and more heavily armed German units would finish them off. If that did not work, retreating Axis forces would inflict what losses they could on the advancing Allies as they retreated toward Messina.

The Axis plan was for German and Italian units to make a coordinated attack on the beachhead, but communication problems and the incompetence of the HGPz resulted in piecemeal attacks instead.

Initially, two Italian columns from Gruppo Mobile E attempted to drive the Americans out of their lodgment. As anticipated, the eastern column moved south along the Niscemi road toward the Italian strongpoint at the Piano Lupo road junction. Before they reached it, they encountered a blocking position manned by men from Lt. Col. Arthur Gorham’s 505th Parachute Infantry.

The Americans ambushed the approaching column and drove off a subsequent attack. Italian artillery opened fire and allowed them to fall back to hold the position at the crucial road junction, now also in American hands.

As they were preparing to move, naval gunfire began falling on the Italians, called in by an observer with the 1st Division’s 26th Infantry Regiment that was approaching from the beach. The Italian infantry went to ground but the tanks continued toward Gela. There they met the 16th Infantry, which knocked out several and forced the rest to flee into the hills.

The western Gruppo Mobile E column also tried another tank/infantry attack on Gela. The co-ordination was poor and the tanks arrived first without supporting infantry. The Rangers drove the tanks out of the city, then ambushed the enemy infantry when it arrived and, with the help of naval gunfire, destroyed it.

Because of the wretched roads, the available units of the HGPz, about the equivalent of an American RCT, were formed into two Kampfgruppen and sent to attack early in the morning. But the HGPz’s lack of training and cohesion, together with its lack of familiarity with the area, delayed the beginning of its move until 2 p.m.

The western HGPz column, aimed at the Gela area, was a tank-heavy force that made good time until it encountered Gorham’s 505th paratroopers—now reinforced by elements of the 16th Infantry and in contact with warships off the coast. The attack failed in the face of accurate small-arms fire, mortars, and naval artillery.

The eastern HGPz column, made up of a company of Tiger tanks and two battalions of panzergrenadiers, fared worse. Two of the temperamental Tigers broke down and the column found itself repeatedly having to countermarch around narrow village streets and other obstructions.

The panzergrenadiers reached the American positions first but were stopped by a few infantrymen supported by nothing heavier than their mortars. A major part of the problem was that the commander of the panzergrenadiers was a grounded (because of nerves) bomber pilot who had no experience or training in ground fighting.

The commander was replaced and the grenadiers again attacked the thinly held outposts of the 45th Division’s 1/180th Infantry. This time they overran the Americans, capturing much of the battalion and pushing back the remainder until they encountered the 3/180th that was able to stand its ground.

Later that day, German tank/infantry columns attacked again, but small-arms fire stopped the infantry and more naval gunfire fell on the tanks. In mass panic borne of inexperience, the grenadiers fell back in disorder, and the attack was called off by 3 p.m. There was no direct air support for the American landing; none of the requested flights arrived. Instead, there were squadron-sized sweeps of enemy-held territory by P-38s and P-51s configured as dive bombers that failed to stop the columns moving up to attack.

Axis aircraft were plentiful, flying 481 sorties against the beachhead.

That night, more paratroopers from the 82nd arrived. Again, a lack of aircrew training and poor mission planning told. It was a terrible blunder that the flight path of the troop carriers passed over the Allied fleet and the invasion beaches that bristled with antiaircraft guns manned by tired, jittery seamen and soldiers.

The Air Force refused to give the Army and Navy the routes of their aircraft until it was too late to ensure that all the antiaircraft gunners were notified. Probably not all of them received the word to hold fire as the airplanes passed over and, in fairness to them, they had already been subjected to sporadic attacks during the day and a night attack by the Luftwaffe.

This caused another fiasco that cost more American lives. American aircraft were shot down by American gunners; other planes were scattered so that the dispersal of the paratroopers was worse than the previous drop. Twenty-three aircraft disappeared, presumably falling into the sea. Surprisingly, some paratroops actually landed in or near their assigned drop zones.

The following day was the most crucial one in the battle for Sicily. During the previous night, the Americans had used the respite from the day’s fighting to move several more miles inland, allowing the defenders to engage the attackers further from the actual beaches. The HGPz and the Livorno Divisions marshaled six columns for the attack. Their attack forced back the outpost line, including the paratroopers’ blocking position and penetrated well into the beachhead, but only at great cost.

Livorno’s columns attacked the Rangers’ around Gela across harvested wheat fields and took more than 50 percent casualties before being forced back. Livorno was finished as a fighting force.

A panzer column broke through the 1st Division positions and into the Gela plain, raking the supply dumps with fire. The infantry resisted with bazookas and antitank guns that destroyed several panzers.

As the morning went on, American artillery and mortars began to play an increasing part. More guns came up and Shermans broke free of the soft sand and the barbed wire clogging their tracks. Their 75mm guns outranged the 50mm guns on the Pz3s that made up the bulk of the attack and had greater penetrating power. (The German army considered even the older Lee tanks they met in Africa superior to the Panzer IVs. This was before the IV was upgunned and up-armored.) The panzers’ attack was repulsed with heavy losses.

Allied naval support was crucial. The ships’ guns equaled four or five battalions of medium artillery, and they pounded the German columns as they advanced until they were mingled with American units. As the enemy withdrew, the guns pummeled their broken remnants again.

East of the Gela plain, the 180th Infantry was forced back to the beach. Here, too, naval fire support played a crucial role as the destroyer Beatty fired 800 rounds of 5- inch shells into the advancing Germans.

Near the eastern flank of the lodgment, Colonel Gavin arrived from where the drop had left him in time to organize scattered groups of paratroops and men of the 45th Division into a thinly stretched defense along the Biazza ridge. They had only a few 81mm mortars and two 75mm howitzers in support of their stand; the shale of the ridge prevented them from digging in.

The Germans were still paying the price for manning the HGPz with poorly prepared Luftwaffe personnel. They were “nervous,” and their attacks were confused and lacked aggressiveness. This was fortunate for the Yanks, given the “vast mismatch between the [strength of the] two sides.”

Throughout the day, U.S. soldiers and small units joined the fight. Toward evening, six Shermans arrived and Gavin mounted a counterattack; the Germans broke off the attack and went on the defensive.

That night, General Allen, always a proponent of hitting an enemy when it was off balance, ordered his 1st Division to make another night attack.

For the first three days, the British faced negligible opposition and pushed their troops hard to take advantage of it. Their advance up the eastern coast was not checked until they encountered Team Schmalz east of Syracusa.

General Alexander told a historian after the war that he didn’t develop an overall plan for Sicily’s conquest beyond the initial landing areas, preferring to see how things developed. When the beachheads were large enough to allow logistical buildup and maneuver room, his intention was to strike north across the island. But that intention was not developed into a detailed plan.

Here, British failure to understand how much the American Army had improved— and Alexander’s reluctance to commit, ahead of time, to a plan for the rest of the campaign—combined to create a serious problem for the Allies.

On July 13, Alexander visited Patton’s headquarters with a party that did not include any of the American liaison officers assigned to him; Patton and Bradley were quite insulted. He should have learned at the meeting that Patton’s troops were fighting effectively and were well positioned to push across the island.

Bradley expected to move north on the axis Vizzi-Enna. The inter-army boundary was east of the road that linked them and he could reasonably infer from Alexander’s silence that he had permission to do so. Alexander did give Patton permission to extend his beachhead further west to the vicinity of Agrigento—as long as he avoided major engagement. But he did not disclose that he had already decided the Eighth Army would make the advance across the island. The Americans were to hold in place and protect Monty’s flank.

The Eighth Army was ordered to move boldly to trap the forces facing the Americans. Alexander made this decision before Montgomery developed the same plan and proposed it to his superior the day before. Alexander’s order arrived that evening.

Alexander’s motivation can only be inferred. He seems to have had the fixed idea that there was a need to protect Montgomery’s left flank from a counterattack out of the western part of the island. But, by the 12th, the Allies were receiving abundant signal intelligence that made it clear that there were only a few small German units there. There were a considerable number of Italian troops present, but they war-weary and could be ignored.

Alexander’s decision meant that the inter-army boundary, which had been set before the invasion and which Montgomery’s troops had already crossed without authorization, would be shifted westward. This would give the British the use of the road from Vizzini, which they had just reached, on to Enna in central Sicily and the north coast.

It was a bad decision, poorly implemented. On the 14th, before the order arrived, American infantry and artillery of the 45th joined in the British attack on Vizzini on the initiative of the local American commander. In spite of the distraction of a German counterattack, the 45th could have committed considerably more power to the British attack on the town.

Instead, the order for a boundary shift meant 45th had to be redeployed to the left of the American position, a 90-mile trip, taking it out of action for days.

When Patton’s headquarters received the order, the Americans were appalled. As Maj. Gen. John Lucas, Ike’s representative at the headquarters, put it, “Once the momentum which we have gained is lost, momentum is difficult to regain.” Bradley was still furious about it in the 1980s when he was writing his second autobiography.

The American Army was the right army to make the attack across the island. It was led by a former cavalryman whose audacity would become legendary. It was better equipped than the British, with more and better supporting vehicles making it far more mobile. But Alexander’s plan showed his contempt for the American Army and, because of that, his plan would waste its mobility and striking power.

The Eighth Army was the wrong army to make the attack. Montgomery had insisted that the British assign only battlehardened formations to the invasion, but there was a strong feeling in those formations that they had already done their part.

Further, Montgomery had been impressed when Italian units in Tunisia, their backs to the sea, fought desperately in the last weeks of that campaign. He expected Italians in Sicily to do the same, so he had allocated much of his supply tonnage to ammunition at the expense of vehicles, many of which went down with a ship.

When Italian opposition simply melted away, the Eighth Army was not in a good position to take advantage of it. The easy advances Montgomery’s troops had experienced encouraged Monty to drive them hard to advance as far as possible before the defense stiffened. By this time, many of the British troops had already walked more than 50 miles carrying full kit plus extra food and ammunition in humid, 100-degree weather. They were fatigued and more than a little “browned off.”

Monty’s plan was for XXX Corps to drive northwesterly behind the HGPz troops facing the American beachhead and trap them. Then it could continue along Highway 117 toward the north coast.

Meanwhile, XIII Corps would drive to the northeast along Highway 114 toward the Catania plain and its airfields.

Almost immediately the northwesterly drive ran into problems at Vizzini. There it hit its first serious opposition from HGPz troops who were beginning to learn their business. They held the town for two days and fell back only a short distance to a new position from which to continue to slow and inflict casualties on the British. American artillery was well positioned to pummel the retreating Germans but was forbidden to fire into Eighth Army territory.

Montgomery turned his attention to the northeasterly advance. The 50th Division would begin by driving Team Schmalz from their positions around Lentini while the 5th Division would advance along the coastal road. The advance would not move much further unless the British first captured the bridge over the Lentini River and the Primsole Bridge over the Simeto River. The first was close to the sea—and to existing British positions. Commandos captured it and were quickly relieved.

Primsole was a greater challenge. Some of the Luftwaffe’s 1st Parachute Division had dropped in and were defending the east side of the river. They were among the most determined and effective infantry in the world. The area near the bridge was covered with vineyards and orchards that gave good cover to defenders and made daylight attacks nearly suicidal. British glider troops were tasked with capturing and holding it until the 50th Division arrived.

Their drop on the night of the 13th was as scattered and disorganized as the earlier ones. Several small groups assembled near the bridge and captured it from an Italian security force. They held it for 16 hours until German counterattacks forced the remnant of the glidermen to withdraw.

Later that day, a battalion of Durham Light Infantry (DLI) arrived near the bridge and the next morning made an assault that was reminiscent of British attacks in France in WWI—and about as successful. It was repulsed with crippling losses.

The British were preparing to make another daylight assault when Lt. Col. Alastair Pearson, commander of 1st Battalion of the Parachute Brigade, muttered, “I suppose you want to see another battalion written off, too.” The commander of the Parachute Brigade persuaded the 5th Division to delay the attack until late that night and to follow a covered, more indirect route.

Initially, that attack was successful but, not for the last time, British radios failed at a crucial moment. The follow-up force was not ordered to advance until after daylight, giving the Germans time to prepare. The British continued to attack into the teeth of the German defenses until the 18th, taking more crippling losses. The operation, which Montgomery had planned to break open a quick route for the British to Messina, was a failure. Catania would not fall until early August.

Patton received Alexander’s order on the 13th stoically, not realizing that, according to British Army practice, commanders at his level were entitled to argue for an order to be modified or rescinded. Montgomery told Patton that if he received an order from Alexander that he did not like, he should ignore it; that’s what he—Monty—did. Montgomery was serious. His attitude was not common among British generals, but it was almost unheard of among Americans.

After the stuttering start in North Africa, it was “imperative” that the troops, the people back home, and the British all saw American soldiers operating boldly and effectively. For the alliance to function well, both parties needed to have an accurate understanding of the other’s strengths and weaknesses.

Patton flew to Tunis to make a case for an American advance north and west. Alexander claimed he had intended Patton to do just that, but his staff had not yet sent the orders.

The plan, however, was ill-considered. There was no fight left in the Italians and the Germans were abandoning that part of the island as fast as possible. It would not have taken much more than a battalion of MPs to handle prisoners, a Civil Affairs detachment, and an armored division combat command to provide muscle and overrun the western half of the island.

Meanwhile, the bulk of the American Army could have been advancing to the north and east while the Germans had not completed developing their defenses in that area. General Lucas wrote in his diary on the 15th that that would have been the better plan. Bradley said much the same in his memoirs.

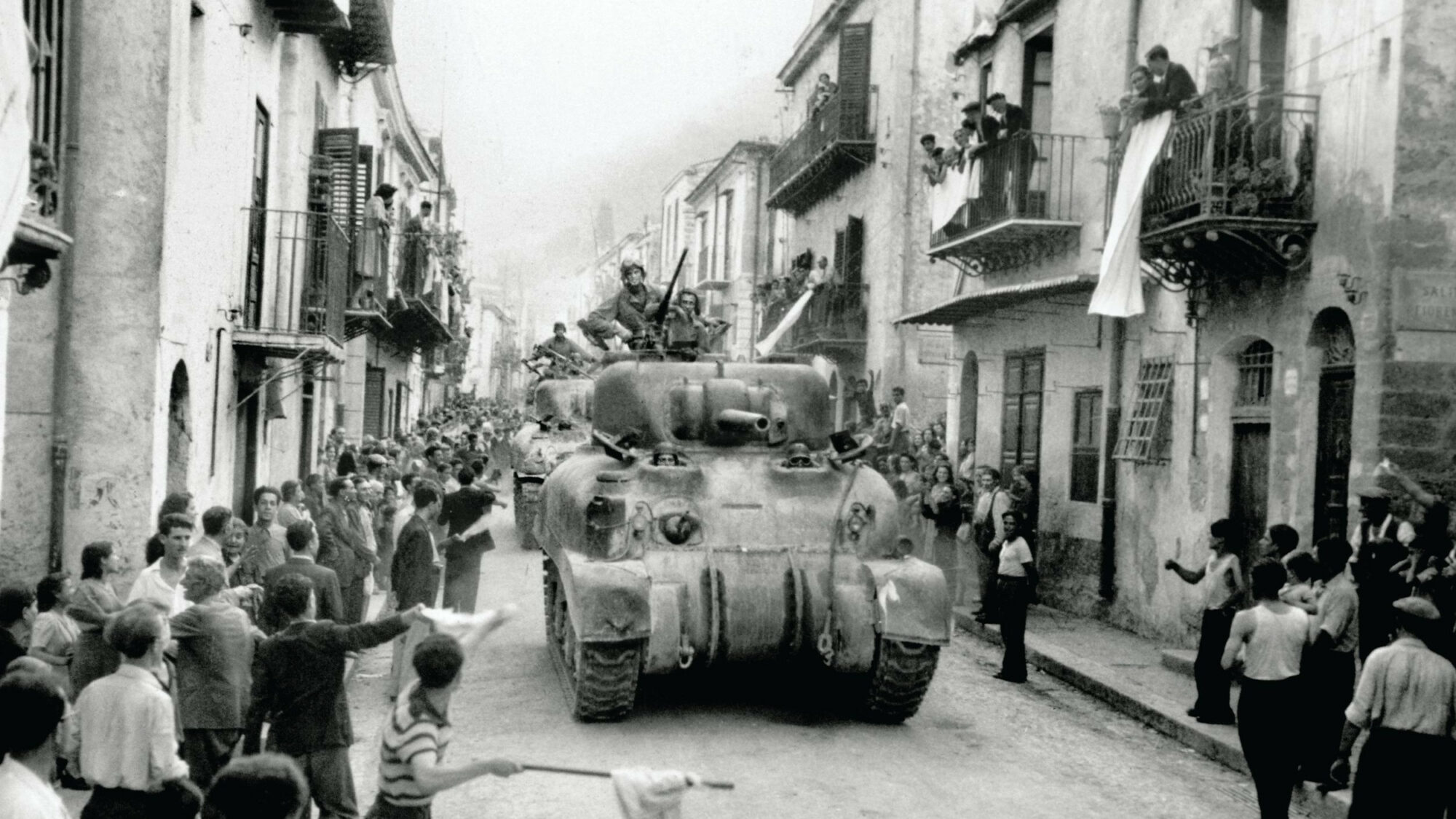

Patton formed a provisional corps of the 3rd Infantry, 82nd Airborne, 2nd Armored, and two Ranger battalions to make the advance to the west over primitive roads and rugged terrain— brilliant demonstration of American mobility. One battalion marched 55 miles over mountain trails in 33 hours. The advance on Palermo on the northern coast began from positions the 3rd Division occupied on the left flank of the American sector around Agrigento on the 19th; by noon on the 22nd, the 3rd was overlooking the city.

The German withdrawal allowed them to form a shorter front, make the Allies pay a high price to attack it and possibly be a base for a counteroffensive. They fortified a series of strong points along the Etna Line that ran from Paterno on the east to Leonforte in the west, facing the British and Canadian troops that were moving toward the northeast. The strongpoints blocked the few routes through the rugged mountains.

The line marked the end of the Germans’ voluntary withdrawals, and the thinly stretched British and Canadian units fought valiantly to break it. First, Assoro needed to be captured to clear the way for an attack on Leonforte. The Canadians assigned the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment—“the Hasty Petes”—to capture Assoro. The lynchpin of the defenses there was an 11th century Norman castle topping a crag above the town, with only a single winding road up to it.

The commander and an intelligence officer moved forward to evaluate the situation, but the Germans spotted the reflection from their binoculars. They were both killed, which left Major John Stewart, the Lord Tweedsmuir, in command. He formed a force of 20 volunteers and one officer from each of his rifle companies to infiltrate up the cliff on the eastern face of the crag to the castle.

Their gear was stripped to weapons, ammunition, water, and one long-range radio. On the night of July 20, the men set out in bright moonlight on an incredibly difficult forced march over some of the most rugged terrain in Sicily.

They made their way to the foot of the cliff below the summit. After a hair-raising climb, they reached the castle and captured its only occupants—an artillery spotting team with an excellent telescope—without alerting the Germans below.

As the Germans prepared their breakfasts and did morning chores, the Canadians opened fire. The day was spent holding off German counterattacks and enduring their shelling. Using a radio and the captured telescope allowed the Canadians to bring deadly accurate artillery fire on their attackers while Tweedsmuir brought the rest of the battalion forward. By the end of the day, the town was solidly in Canadian hands.

By this time, it was clear that Montgomery had miscalculated and that his plan to capture Messina by breaking the German defenses with attacks by the Eighth Army on both sides of Mount Etna was not working. Moreover, the left flank of his army was hanging in the air, vulnerable to a German counterattack. The attack up the coastal strip between Etna and the sea was abandoned in favor of a concentration on the other side of the mountain. Lack of transport still slowed the Eighth Army’s movements.

Monty’s troops would fight well and doggedly. But after fighting for so long in North Africa, with more to come in Europe, they were less likely take the chances that greener troops would take. Spread thin, they needed rest and reinforcements.

Alexander and Montgomery had begun the campaign regarding the Americans as barely competent to guard the Eighth Army’s flank. D-day and D+1 battles showed Montgomery that the Americans had become first-rate troops. The clearance of the western half of the island showcased their mobility. Montgomery realized it was going to require an all-out effort by both Allied armies to finish the campaign.

HGPz had shaken down into an effective unit and 15th PzG, a good unit from the beginning, had been joined by the 29th PzG. The terrain where the Germans had fortified their positions favored the defense as much as any terrain in the world.

Monty invited Patton to come to his headquarters for a meeting on the 25th to formulate plans for the rest of the campaign. As one historian commented, “it was noteworthy” that it was Montgomery and not Alexander that took that initiative.

Route 113 along the coast and Route 120 through the interior were the best roads in northeast Sicily. Patton was suspicious and surprised when Montgomery suggested the Seventh Army use them to capture Messina. He also gave Patton permission to cross the boundary line between the two armies if it would aid his attacks.

Toward the end of the meeting, Alexander, in a visibly testy mood, joined them. His mood was not improved by being told how the rest of the campaign was going to be conducted. He had no real choice but to issue orders to implement what the two armiy commanders had already decided. His lack of leadership was clear.

On the 23rd, the 45th Division reached coastal road Route 113 near Termini Imerese, and elements turned both east and west. The battalion moving east encountered newly arrived elements of the 29th PzG at Campofelice, about 40 miles west of San Fratello, the northern terminus of the Germans’ main defensive position.

Route 113 crossed a series of ridges generally running perpendicular to the coast that provided good defensive positions. To clear them, the Yanks usually had to swing inland and flank the defenders. There were few practical routes to do so, which made American attacks predictable and casualties heavy.

Once a ridge was cleared, the engineers could move in to repair the road. Since the Germans had made liberal use of demolitions, only the engineers’ excellent work allowed the advance to move forward at a reasonable pace. If the ridge was wide where it reached the sea, the road was built on a narrow ledge cut into the side of the ridge. If the ridge was narrow, the Italians had usually dug a tunnel through it.

For example, at Cape Calava, the Germans had collapsed a tunnel and slid a section of roadbed down a cliff. Within 18 hours, the engineers had hung “a bridge in the sky” over the missing roadbed that would carry a jeep. After another six hours of shoring, the bridge was strong enough for larger vehicles.

The Allies controlled the sea above Sicily’s northern shore, so attempts were made to flank Germans from that direction. The first American attempt landed a reinforced battalion behind German front lines. As the Germans fought their way past it, both sides took heavy casualties.

The second landing put a larger force ashore, including armor and artillery. Relief took longer than expected and supporting naval vessels had to be called back twice. Eventually, the survivors exfiltrated back to American lines. By the time the next landing was made, advancing troops on land had already passed the landing site.

Later in the campaign, Eighth Army reinforced a commando unit which landed in an attempt to cut off a German rear guard, but the Germans eluded the commandos. The final phase of the campaign involved cracking the Etna Line and capturing Messina.

Allen’s 1st Infantry completed the capture of Enna and drove north to Petralia. There they turned east along Route 120 toward Troina—and nearly a week’s fighting in one of the most controversial battles of the campaign.

There were no good maps, and fog prevented good aerial photos until late in the battle.

Intelligence predicted the Germans would continue to fight a delaying action, inflict casualties, and then withdraw to positions about five miles east of the town. The attackers did not realize that the Germans had the whole of 15th PzG available.

Troina had significant advantages for the Germans. The barren terrain made German artillery observers especially effective, and there were good positions for their guns that controlled movement along Route 120 and overlooked the few avenues of approach, which made encirclement difficult.

Initially, only the attached 39th Infantry Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division was committed, which did not allow simultaneous movement against the town and the hill positions that were placing direct fire on Route 120. The attack made some progress, but the troops were thrown back by a counterattack that night.

The next day, the 39th attacked again with the support of another regiment and a battalion of French colonial infantry. Strong German artillery fire stopped the French and the 39th’s attacks in their tracks and kept the other regiment from advancing more than half a mile.

The next day began with an attack across the divisional front into the teeth of a tenacious German defense. German tactical doctrine called for vigorous counterattacks, and the defenders did so with a vengeance that day. Were it not for the massive American artillery support, some 165 guns, the lead battalion would have been overrun.

Another German counterattack came so close to the American positions that the American artillery had to stop firing in support. One move was defeated because German artillery observers could see the troops attempting to cross open, rocky ground.

The battered German defenses held the attackers to gains of one or two miles. The next day’s attack focused on the town but did not expel the Germans.

On August 5, the German defenses began to crack. The newly arrived 60th RCT of the 9th Division reinforced the attempt to attack the town from the north.

Meanwhile, the British and Canadians had made solid progress to the south and threatened to envelop Troina from that direction. The Germans had taken 1,600 casualties or about 40 percent of the 15th PzG, and air attacks had made their supply situation desperate. They began to withdraw to positions around Cesaro, but their vehicles and heavy equipment kept on going to evacuation points around Messina.

About two weeks before the Allied landings, the Germans, ahead of a withdrawal to the Italian mainland, had appointed a naval officer commander of the Messina transport facilities; he found a mess. There were several flotillas of ferries run by German and Italian agencies, including one run by the German infantry. He reorganized them, added more routes outside of the immediate area around Messina, and increased the number of vessels in service.

The most effective additions were flatbottomed barges with a front ramp and Siebel ferries—a pair of heavy bridge pontoons with a deck built over them and engines mounted in the rear. The daily cargo flow increased by a factor of 10.

The defenses of the Messina Strait and the transport system up to and away from the strait was another mess. German commander Albert Kesselring appointed a German colonel to organize the air-defense assets in the area and the movement of troops and supplies toward and away from the strait.

Allied air attacks stayed at high altitudes to avoid anti-aircraft fire and did not do enough damage to prevent the Axis troops from getting away. Moreover, the Italians had considerable artillery capable of damaging or sinking Allied warships and the Germans added more. No Allied surface interdiction was attempted.

The Axis units that crossed the strait after inflicting heavy damage to the Seventh and Eighth Armies were rehabilitated and gave Germany further good service. So the Allied victory is rightly regarded as flawed.

Clearly, the Allies conducted the battle badly. One can only speculate about what the outcome would have been if, on the 13th, Alexander had ordered the Seventh Army to move aggressively in a northeastward direction. That would have put leading elements on the north coast and heading east by about July 19. The 29th PzG began arriving on the island on the 22nd and encountered the 45th Division two days later. The conquest of the island might have ended with a substantial prisoner haul if the encounter took place further east—and before the Germans had time to dig in.

Even though flawed, the battle was still part of a momentous change in the fortunes of the antagonists. It succeeded in reducing pressure on the USSR as Hitler called off Operation Citadel on July 12.

The Germans never mounted another successful offensive.

The fall of Sicily also spelled the end of Mussolini, who was ousted by the Fascist Grand Council; Italy declared itself neutral.

Italy’s defection meant that Germany had to supply troops to replace the Italian troops guarding France’s Mediterranean coast and garrisoning the Balkans, as well as using an entire army to garrison Italy itself.

Germany committed most of four divisions to the Sicily battle, three of them first-rate, well-trained and equipped units.

The commitment of the HGPz, without adequate training, was a harbinger of things to come; it would become increasingly common during the rest of the war.

By the time of the Allied landings in France, Germany still had a considerable number of well-trained and equipped divisions, mostly panzer and panzer grenadier units. But many of the remainder were illequipped, poorly trained, and manned by men with uncertain loyalties.

Sicily made it clear that American failures during the early part of the North Africa campaign were primarily caused by inadequate training. After Sicily, the U.S. could be confident that, with rare exceptions, the units that had completed the prescribed army training program would give a good account of themselves.

Ike, too, had “improved dramatically” during his service in the Mediterranean.

He acquired the tactical and strategic experience to clearly see what authority the Supreme Commander needed. In France he demanded, and got, “direct command of the whole vast enterprise.”

At his insistence, before the Normandy landings, the tactical air forces were employed to damage the French transportation system to seriously slow the movement and build up of enemy reinforcements. This was an important factor in the Allies’ success in Normandy.

After Sicily, there was still heavy fighting ahead in Italy, but the balance of forces had moved decisively in favor of the Allies.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments