By Al Hemingway

“You either loved him or hated him,” one former Marine said of Gregory “Pappy” Boyington. “There was no in-between.”

What kind of man was Boyington, who could assemble of group of young, inexperienced pilots and mold them into one of the most successful fighter squadrons in Marine Corps history? Yet, just a few months earlier, while serving with the famed Flying Tigers in China, he was reviled by the men who served alongside him.

What kind of man was Boyington, who could assemble of group of young, inexperienced pilots and mold them into one of the most successful fighter squadrons in Marine Corps history? Yet, just a few months earlier, while serving with the famed Flying Tigers in China, he was reviled by the men who served alongside him.

The answer is not an easy one. In his new book, Black Sheep: The Life of Pappy Boyington (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 288 pp., photos, illustrations, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover), historian John Wukovits takes a hard look at the troubled aviator’s life.

Boyington’s childhood was anything but a happy one. Born in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, in December 1912, his father was a dentist and his mother played piano in music halls to accompany silent films. The two fought constantly. His father, who possessed a violent temper, accused his mother of being unfaithful. They finally divorced, and Boyington’s mother married a man named Ellsworth Hallenbeck, a bookkeeper for a saw mill. When their home was destroyed by a fire, Boyington’s birth records were also lost. He would not discover his real name until he joined the Marine Corps.

Unfortunately, Hallenbeck had a dark side. Not only was he a heavy drinker, but some family members said that he may have sexually abused some of the children. There has never been any evidence to suggest that Boyington was a victim.

Boyington’s escape was flying. After witnessing barnstormers at the county fairs, he was hooked. Although he struggled with the classroom instruction, he was “one with the air” when he was flying. He was commissioned a second lieutenant and attended Basic School in Philadelphia. He was then assigned to the 2nd Marine Aircraft Group in San Francisco.

Married with a child, Boyington’s financial situation looked bleak until he learned about an all-volunteer group of American pilots being formed to fight the Japanese in China. Like the others, Boyington had to take a leave of absence from the Marine Corps to join the American Volunteer Group, as they were officially called.

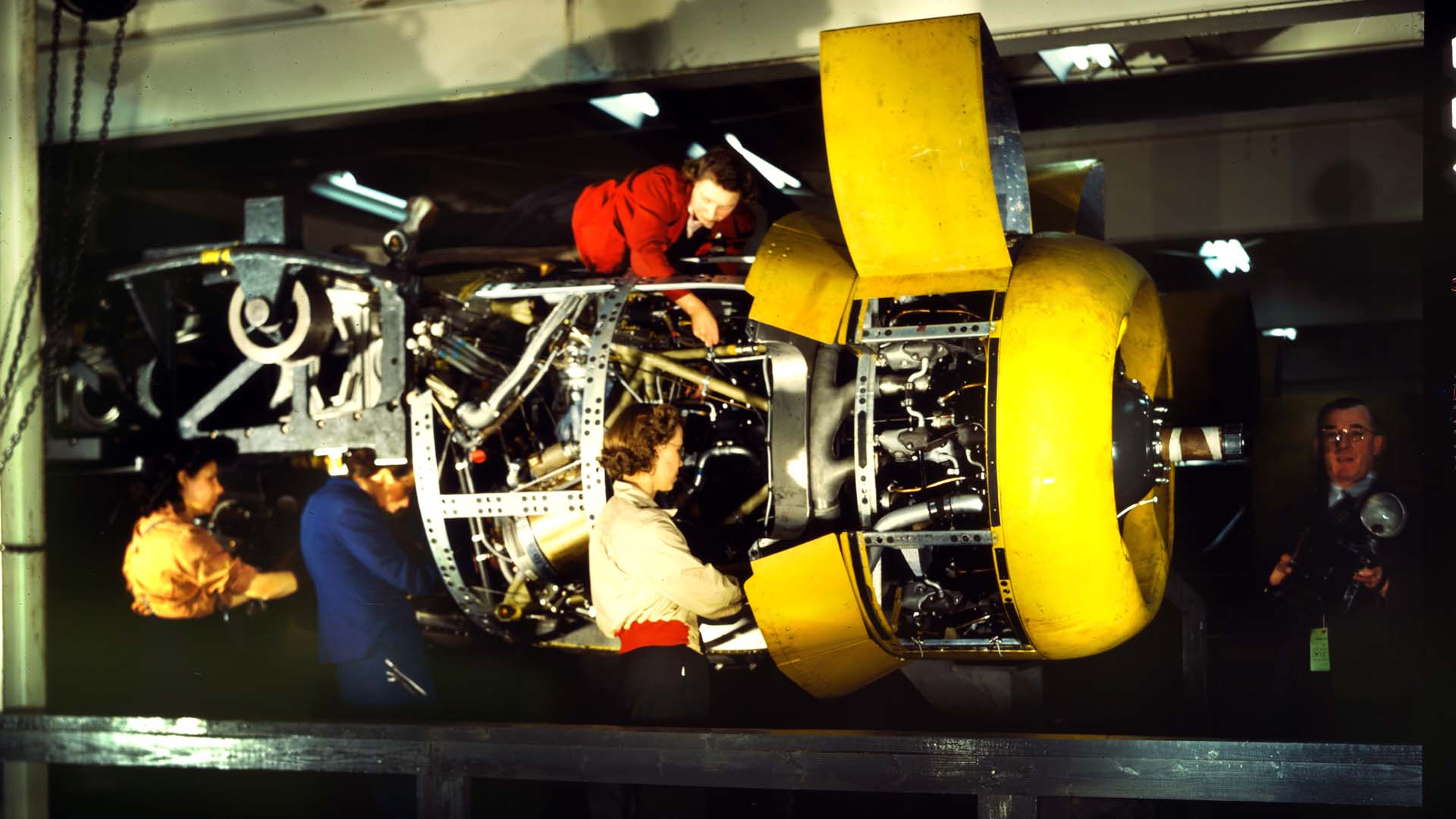

After a long sea voyage, the fliers arrived in Burma, living in very austere conditions, before transferring to China to begin their training on the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, a single-engine fighter plane, under the auspices of Army Air Corps legend Claire Chennault. During those bleak, early days of World War II, immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the American public had little to cheer about, until Chennault’s small band of daredevil pilots made the news. Because of their distinctive tiger’s teeth insignia, designed by Walt Disney, the press started referring to them as the Flying Tigers. The name stuck.

Unfortunately, Boyington’s tenure with the unit was not a rewarding experience. While in class, listening to a lecture on tactics, he embarrassed Chennault. The elder pilot never forgot.

To Boyington, flying escorts for bombers was mundane duty; he wanted to dogfight with Japanese Zeros to earn additional money for any plane he shot down. Unfortunately, it was his drinking and brawling that got him in hot water with Chennault, and it would eventually cost him the command of one of the squadrons. There is also evidence that Boyington had fabricated the number of kills he had while a member of the Flying Tigers.

One thing that Boyington did learn while serving with Chennault was his “innovative methods.” Although they hated each other, he would remember what he had learned and apply it when he commanded the Black Sheep Squadron.

Contrary to popular myth, the pilots of VMF-214, later called the Black Sheep Squadron, were not misfits or incarcerated in Marine brigs. They were young and inexperienced yes, a bit unconventional, like their squadron commander, but they were good. Under Boyington’s tutelage, he shaped them into one of the greatest fighting groups in the Marine Corps. Their weapon was the Chance-Vought F4U Corsair, a fighter the Japanese called the “Whistling Death.” Finally, Boyington had a plane that could match the Zero in aerial combat.

Before long, the Black Sheep Squadron was racking up impressive kills against the enemy. Newspapers quickly caught on and gave them quite a bit of press to raise the morale of a war-weary American people. Boyington’s count rose rapidly, and soon he had tied pilot Joe Foss’s record of 25.

On January 3, 1944, while on a mission over Rabaul, Boyington broke the record, but was shot down and taken captive by the Japanese. For the next 20 months, he was held as a prisoner of war. When he was repatriated at war’s end, he returned stateside and was awarded the Medal of Honor and Navy Cross. He left the Marine Corps with the rank of colonel.

Boyington died in 1988. He was indeed a very complex individual. As the author points out, many of his men overlooked his weaknesses and focused on his strengths. They commented on “his quality of leadership,” but were saddened that he could not “reach the heights he could have,” except when he was in the cockpit of a plane.

Battle Yet Unsung: The Fighting Men of the 14th Armored Division in World War II by Timothy J. O’Keeffe, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 336 pp., notes, photos, $32.95, hardcover.

Battle Yet Unsung: The Fighting Men of the 14th Armored Division in World War II by Timothy J. O’Keeffe, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 336 pp., notes, photos, $32.95, hardcover.

While much has been written of the fighting in Normandy and the bitter struggle at the Battle of the Bulge, little attention has been paid to the equally bloody combat endured by U.S. forces in southern France and Germany from late 1944 until war’s completion.

One such unit that participated in the campaigns through the underbelly of France and into Germany itself was the 14th Armored Division, which landed in Marseille, France, in October 1944. As part of the Sixth Army Group, the “Liberators,” as they were called, marched northward, crossed the Rhine, and fought a series of pitched battles with the German 19th Army. The terrain could prove to be treacherous as the soldiers moved through the Rhone Valley, Alsace, and the Vosges Mountain chain in pursuit of the enemy.

After bitter combat in places like Gertwiller, Benfeld, and Barr, elements of the Sixth Army, which included the 14th Armored Division, cracked the German defenses and poured onto the Alsatian Plain before Christmas 1944.

On December 17, the division penetrated Germany, running headlong into the seemingly impenetrable bulwark known as the Westwall or Siegfried Line. Unfortunately, due to the deteriorating situation in the Ardennes, the unit was ordered to withdraw and take up defensive positions while other Sixth Army units were sent to reinforce the beleaguered troops in the Ardennes.

This movement of units did not go unnoticed by the German high command. Realizing that they were in a vulnerable position, German Army Group G launched Operation Nordwind, the last major enemy counteroffensive of World War II. Soon, Task Force Hudelson, named after its commander Colonel Daniel Hudelson, found itself in a very precarious position. As many as five enemy divisions had surrounded the task force which, for the following week, fought continuously to delay the German juggernaut from advancing. Finally, reinforcements arrived and drove the panzer units back but not before the Liberators slugged it out with the enemy at the Battle of Hatten-Rittershoffen. When the fighting had stopped, the 14th Division had lost 62 medium tanks. For outstanding bravery, the 14th received two presidential unit citations.

As the unit raced toward Berlin, it also freed an estimated 200,000 Allied prisoners of war. The author has done an incredible job in shedding light about an often neglected but important role this unit played in the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Killing the Bismarck: Destroying the Pride of Hitler’s Fleet by Iain Ballantyne, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2010, 288 pp., notes, index, photos, $50.00, hardcover.

Killing the Bismarck: Destroying the Pride of Hitler’s Fleet by Iain Ballantyne, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2010, 288 pp., notes, index, photos, $50.00, hardcover.

When Prime Minister Winston Churchill received the awful news that the battlecruiser HMS Hood, flagship of the Home Fleet, had been sunk by the German battleship Bismarck, he was sickened and infuriated. He quickly issued orders to naval officials in a terse statement that needed no further explanation, “Sink the Bismarck!”

That order spurred a hunt that has become legendary over the years. Several days later, when biplanes from the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal spotted the massive vessel steaming toward friendly waters, they fired torpedoes, with one of them causing damage to the ship’s rudder. Because she was forced to reduce speed, British warships finally caught up to her. In the ensuing sea battle, nearly 3,000 shells were reported to have been fired at the Bismarck, but only a few actually penetrated her heavy armor. For two hours, the ship was pummeled by the British, until she finally went under.

Ballantyne, however, has obtained fresh material to bring a whole new perspective to the chase and eventual sinking of the Bismarck. He tells the story from the British side, including eyewitness accounts from officers and crew members.

Another fascinating aspect to his book is Appendix 1 titled “Busting the Myths?” Here, the author attempts to answer questions that some historians have been asking for years. Could the Bismarck have surrendered? Could they sink her by gunfire? The Royal Navy’s Dark Secret? These are just a few of the intriguing queries that readers will surely find interesting.

As far as what really sunk the Bismarck, Ballantyne writes that undersea explorer David Mearns’s expedition concluded that “together with the torpedoes, the British guns punched enough holes in the German battleship to take her down regardless of efforts by her own sailors, whom it was claimed had really sunk Bismarck by setting off scuttling charges.”

The author has written an excellent account of the short-lived operations of the Bismarck. Despite knowing the outcome of the events on May 27, 1941, he has still managed to pen a suspenseful narrative that will keep readers on the edge of their seats.

Surface and Destroy: The Submarine Gun War in the Pacific by Michael Sturma, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 260 pp., notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Surface and Destroy: The Submarine Gun War in the Pacific by Michael Sturma, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011, 260 pp., notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Whenever the image of a submarine comes to mind, people conjure up thoughts of underwater vessels, silently patrolling the waters hundreds of feet beneath the ocean, searching for the enemy. Armed with torpedoes, they would lock in on an enemy ship and hopefully send her to the bottom. It was an impersonal style of warfare. The submarine would maintain its anonymity and quietly sail away from the scene.

However, in this book, the author depicts another side of submarine combat that is rarely discussed—the gun war. Prior to World War II, deck guns were considered unnecessary, especially in the Pacific. By 1943, naval officials realized that armament for the deck of subs was becoming essential, especially toward the end of the war.

Manning deck guns was a dangerous job on a sub. Sailors would be called upon at a moment’s notice to rush through the hatches, man their weapons, and meet the enemy face-to-face. Numerous times they engaged junks, sampans, sailing boats, and schooners, attempting to transport supplies.

Here, the war became personal. As Seaman Ignatius “Pete” Galantin, a crew member of the USS Sculpin, observed, “How different, how personal was war when the target was flesh and blood instead of steel.”

Naval historian Michael Sturma has penned an intriguing book on a virtually unknown aspect of a submariners’ war—coming to the surface to encounter the enemy—and meeting him in close quarter combat.

No Surrender: A World War II Memoir by James J. Sheeran, Berkley Caliber Books, New York, 2011, 320 pp., $25.95, hardcover.

No Surrender: A World War II Memoir by James J. Sheeran, Berkley Caliber Books, New York, 2011, 320 pp., $25.95, hardcover.

A combat veteran’s personal memoirs always make for exciting reading—especially when the individual was a paratrooper who jumped with the 101st Airborne Division on D-Day, was captured, escaped, and then found himself a member of the Maquis—the French Underground fighting against the Nazis.

Such a man was James Sheeran. Although dyslexic, he had an incredible memory that could recall every detail of his astonishing adventures during the war. The New Jersey native, full of that “Screaming Eagle” fighting spirit, could not fathom sitting out the entire conflict as a prisoner of war.

Sheeran and several of his comrades made their escape from a German POW camp. They dodged enemy patrols and finally found themselves in a barn to be befriended by a local. For four months, before finally being reunited with his unit, he fought alongside French Underground fighters. Sheeran also participated in the ill-fated Operation Market Garden in Holland and the fighting at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge.

Years after the war, Sheeran would return to France and meet his French comrades. They swapped stories, and he was given his old lunch box, which he had carried with him into combat and left behind. That lunch box meant the world to him.

Sheeran went on to have a successful career in politics, serving two terms as mayor of West Orange, New Jersey. He was appointed a Chevalier of the Order of the Legion of Honor. Sadly, he passed away in 2007, but his heroic exploits will live on with the publication of his book.

Cry Havoc: How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941 by Joseph Maiolo, Basic Books, New York, 2010, 512 pp., notes, index, photos, $35.00, hardcover.

Cry Havoc: How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941 by Joseph Maiolo, Basic Books, New York, 2010, 512 pp., notes, index, photos, $35.00, hardcover.

At the conclusion of the “war to end all wars” in 1918, Europe was in a shambles. Four years of bloody, trench-style combat had depleted and ravaged the countryside. One would think that after enduring such a horrifying and climactic event, the European nations would be sick of war and band together to establish a lasting peace. Unfortunately, such was not the case.

In Cry Havoc, the author traces the escalating arms race that engulfed not only Europe, but Japan as well. With the failure of the 1932 World Disarmament Conference in Geneva, countries, chiefly Germany and Japan, continued a military buildup that would eventually plunge the world into yet another global conflict.

The author contends that Hitler was losing the arms race. He had originally wanted to declare war on the Soviet Union with Italy and Great Britain as his allies. That scenario never came to fruition. Instead, he started a world war that he could not possibly win.

“As economic historians have shown, the decisive wealth gap between Germany and its enemies was even wider than most contemporary experts believed,” writes Maiolo. “In retrospect that makes Hitler’s decision to venture into an unwinnable war even more astonishing. That the economic lightweights Italy and Japan followed that path too is doubly astonishing.” n

Short Bursts

Somewhere We Will Find You: Search and Rescue Operations in the CBI, 1942-1945 by Robert Underbrink, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2010, 258 pp., notes, bibliography, photos, $19.95, softcover.

Somewhere We Will Find You: Search and Rescue Operations in the CBI, 1942-1945 by Robert Underbrink, Merriam Press, Bennington, VT, 2010, 258 pp., notes, bibliography, photos, $19.95, softcover.

There was no doubt that flying over “The Hump,” a name given to the eastern portion of the 15,000-foot-high Himalaya Mountain Range sandwiched between India and China, was a perilous journey by air. With no navigational charts or radio communication, high winds and terrible weather, it was a pilot’s nightmare.

However, fly it they did. When the Japanese blocked the Burma Road, airlift was the only alternative. Crews from the 10th Air Force’s Air Transport Command performed yeoman’s duties to ensure that the troops were supplied.

Tragically, crews were lost while attempting to traverse this “Skyway to Hell,” as it was later referred to. In August 1943, the search and rescue operation received top priority—the hunt to locate downed airman was on—an extremely difficult task considering the terrain and the unforgiving weather.

Underbrink’s account brings long overdue recognition not only to American air crews, but also to the British military, civilians, and missionaries, and the indigenous tribes that inhabited the area.

The Secret War in the Balkans: A WWII Memoir by Lt. Col. Richard H. Kraemer, USAF (Ret.), Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2010, 244 pp., photos, illustrations, $9.90, softcover.

The Secret War in the Balkans: A WWII Memoir by Lt. Col. Richard H. Kraemer, USAF (Ret.), Author House, Bloomington, IN, 2010, 244 pp., photos, illustrations, $9.90, softcover.

It is indeed fortunate that retired Lt. Col. Richard Kraemer, USAF, is blessed with a good memory. He is also very lucky to have kept his official flight records and personal flight log and diary to tell the story of yet another part of the war that has been kept under wraps for more than 60 years—the secret war in the Balkans.

As a member of the 60th Troop Carrier Group, Kraemer flew hazardous missions from March 1944 until the Normandy landing on June 6, to supply guerrilla groups fighting the Nazis in Yugoslavia and Croatia. During this time, the unit transported an estimated 7,000 tons of weapons and supplies that would prevent Hitler from moving 500,000 troops to the French coast.

By the heroic efforts of his unit and the clandestine operations of the underground, the author firmly believes that their actions assisted in the success of the D-Day landings and helped shorten the war. Their incredible record of more than 4,600 combat sorties certainly was instrumental in defeating Nazi Germany.

Victory in Defeat: The Wake Island Defenders in Captivity by Gregory J.W. Urwin, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 480 pp., notes, index, photos, illustrations, $38.95, hardcover.

Victory in Defeat: The Wake Island Defenders in Captivity by Gregory J.W. Urwin, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 480 pp., notes, index, photos, illustrations, $38.95, hardcover.

It has always been the mind-set that being held captive by the Japanese in World War II was a harrowing experience. Survivors of the brutal Japanese death camps have gone on record explaining their near-death experiences at the hands of their Asian captors who valued honor over death and viewed prisoners of war as subhuman.

However, the defenders of Wake Island, which included civilians, have a different story. They were indeed fortunate to have had a camp commander who possessed a quality often thought absent in Japanese culture—compassion.

Sub-Lieutenant Shigeyoshi Ozeki was indeed a rare bird. So much so, three Marines from the Wake Island garrison returned to Japan to meet with him and express their gratitude for “his decency and kindness.”

It is indeed strange that the Japanese were so cruel and unforgiving in some internment camps and then displayed great care in others. However, as the author puts it, the defenders of Wake Island “were in the right place at the right time.”

Blitz Spirit compiled by Jaqueline Mitchell, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 208 pp., photos, $14.95, hardcover.

Blitz Spirit compiled by Jaqueline Mitchell, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2010, 208 pp., photos, $14.95, hardcover.

On September 7, 1941, the skies over London were filled with nearly 900 German fighters and bombers. The Nazi air armada rained bombs upon the city that afternoon and later that evening. Caught unprepared, more than 400 Londoners were killed and another 1,600 wounded. The Blitz had begun. For the following nine months, German aircraft swooped down upon English cities in an effort to get the island nation to buckle. However, Adolf Hitler underestimated the will and determination of the British people.

This wonderful little book offers a glimpse into another era, depicting how the government and, more importantly, the English people, managed to survive one of the longest sustained bombing campaigns in military history.

As Prime Minister Winston Churchill later said, “Let it roar, and let it rage. We shall come through.”

U.S.S. Serene, AM-300, Memoirs of a World War II Minesweeper Crew by Darwin D. Horn, Cambria Publishing, Lomita, CA, 2010, 242 pp., photos, $25.00, hardcover.

Enlisting right after graduation from high school, Darwin Horn entered the U.S. Navy when America was in the midst of World War II. He was assigned to the minesweeper USS Serene as a diesel mechanic to assist in maintaining the vessel’s engines.

Horn served on the Serene for more than a year, participating in some of the largest amphibious assaults of the war: Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and the Philippines. At war’s end, the Serene took part in clearing the mines that encircled Japan, China, Formosa, and Korea, which were laid by the enemy in anticipation of an invasion.

Researching the career of the Serene, Horn was amazed to discover that she was later transferred to the South Vietnamese Navy during the Vietnam conflict. On January 19, 1974, she was sunk by Chinese communist forces near the Paracel Islands.

“A very sad ending to a once very gallant little ship,” wrote Horn.

Whitey: From Farm Kid to Flying Tiger to Attorney by Wayne G. Johnson, Langdon Street Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 454 pp., photos, $18.95, softcover.

Whitey: From Farm Kid to Flying Tiger to Attorney by Wayne G. Johnson, Langdon Street Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 454 pp., photos, $18.95, softcover.

There is no doubt that the harsh, rural childhood of Wayne “Whitey” Johnson certainly prepared him for the even tougher realities of war. Eleventh of 14 children, Johnson wrote, “We were poor and didn’t know it.”

When Pearl Harbor was attacked, Johnson enlisted in the Army Air Corps the following day and eventually was trained to fly the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk and the North American P-51 Mustang. Surprisingly, Johnson was assigned to China and became a member of Claire Chennault’s famed Flying Tigers. The Minnesota native participated in the successful raid over Shanghai that destroyed nearly 100 enemy Zeros, most of which never left the ground.

Johnson went on to have a rewarding career as an attorney, serving two cities for more than 50 years. He remained active in the aviation field and received numerous accolades, including having an airport named in his honor. Chennault would have been proud.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments