By Chris Dishman

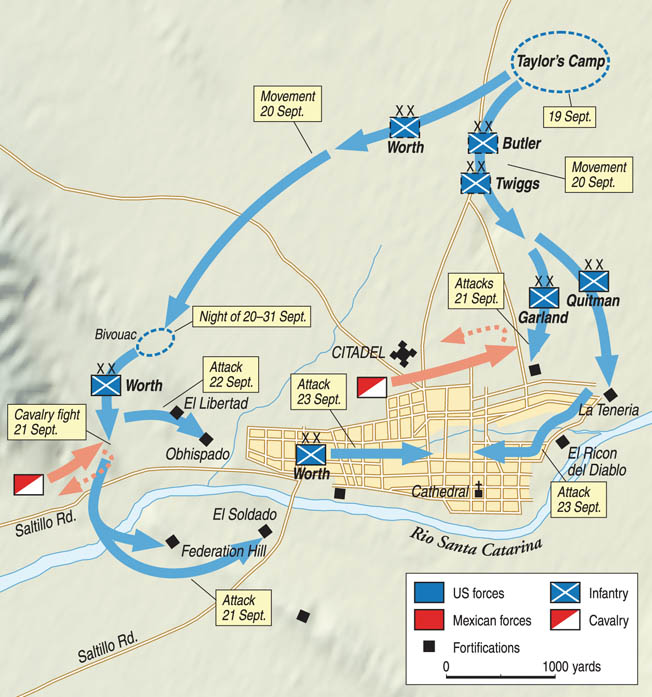

On the morning of September 19, 1846, General Zachary Taylor and his advance party could see little through the mist that shrouded the city of Monterrey, Mexico, Taylor’s next objective in his ongoing northern campaign. The Army of Occupation had recently arrived in Mexico after an arduous journey in steamboats down the Rio Grande from south Texas, sent by President James K. Polk to defend the new state from Mexican incursions. Taylor, dubbed “Old Rough and Ready” for his habitually disheveled look, had already smashed the Mexican Army in the opening battles of the war at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, five months earlier.

After those battles, Taylor pursued the retreating Mexican Army to Matamoros, and after finding that city abandoned, made plans to attack northern Mexico’s largest city, Monterrey. Volunteers poured into Taylor’s army at Camargo, just south of the Rio Grande, where Taylor was preparing for the attack on Monterrey. The hot, humid climate and unsanitary camp practices bred rampant disease at Camargo, which resulted in the death of hundreds of Taylor’s men, largely from yellow fever.

Taylor’s army was about to face its stiffest test yet. At Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, the Americans had utilized a new weapon, “flying artillery,” which consisted of fast-moving, light artillery pieces pulled by horses. During the first two battles of the war, the mobile artillery cut down the pride of the Mexican Army, its cavalry, on the plains of southern Texas. The new weapon, however, would be useless in the streets of Monterrey, where it would be unable to penetrate the fortified structures of the entrenched Mexican forces.

For the Mexicans, there was disagreement about whether to defend Monterrey. The new general in charge of the northern Mexican army, General Pedro de Ampudia, believed that Monterrey had to be defended because the city guarded the primary route into central Mexico. General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, just returned from exile, believed that the city should be abandoned so that the Mexican Army could gather its strength for one last, decisive battle at Mexico City. Those troops would be led by none other than Santa Anna himself, a man wishing to regain past glories and lead the Mexican nation to victory against another foreign aggressor. Ultimately, the Mexican secretary of war allowed Ampudia to have his way—Monterrey would be defended at all costs.

Ampudia, assisted by two of Mexico’s best engineers, set about fortifying the city. The Mexicans constructed two major forts, El Rincon del Diablo and La Teneria, to defend eastern Monterrey and reinforced the old Citadel just north of the city to guard the northern approach. An ornate bishop’s palace atop a high hill looked over the western entrance to Monterrey. Ampudia had picked a good spot for a defensive position. Each rooftop in Monterrey was built with the perfect breastwork: three-foot-high walls surrounded the roofs of each building in the city. The houses were difficult to penetrate from ground level because of their strong double doors, thick adobe walls, and barred windows. Mexican artillery was placed behind barricades on Monterrey’s main cross streets, making its thoroughfares virtual death traps for attacking troops.

The first shots of the battle came when Taylor’s advance party, located about 1,500 yards north of the city, was fired on by Mexican cannons located at the Citadel. One shot bounced just over Taylor’s head and drove straight through his advance party. The volunteers cheered “Old Zach” for his nonchalant response to the danger. Taylor’s fighting spirit and courage already were legendary, and the volunteers, who had not participated in the initial battles, were eager to see their general in action.

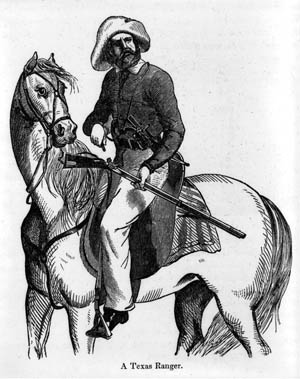

The Texas volunteers who accompanied Taylor’s advance party felt that the artillery shots offered the perfect time to taunt their long-standing nemesis. They rode their horses closer and closer to the Citadel while dodging the fort’s artillery fire. The scene was quite a spectacle for the volunteers, one of whom noted admiringly, “Like boys at play those fearless horsemen, in a spirit of boastful rivalry, vied with each other in approaching the very edge of danger. Their proximity occasionally provoked the enemy’s fire, but the Mexicans might as well have attempted to bring down skimming swallows as those racing dare-devils.”

Taylor settled his forces at El Bosque de San Domingo, or Walnut Springs, which served in peacetime as a picnic site for Monterrey’s elite. Fresh springs, pecan trees, and verdant grass patches created a place more suited for a caballero playing guitar for his sweetheart than an advance camp for an invading army. While the troops enjoyed their sylvan stay, Taylor’s engineers reconnoitered the city to develop a plan for the upcoming attack. Reconnaissance was difficult because numerous gardens, shrubs, and walls dotted the city’s suburbs, obstructing the engineers’ view of the city. Major Joseph K. Mansfield, Taylor’s lead engineer, suggested that their forces take the Saltillo pass, the primary route into Monterrey from the south and west. This action would seal off a Mexican retreat and prevent reinforcements from entering the city.

Taylor ordered General Williams Jenkins Worth, commander of the 2nd Division, to take the Saltillo pass. Worth, one of the war’s best generals, had temporarily resigned from the army earlier in the campaign because of a dispute with Taylor, thus missing the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. Now, restored to command, he was determined to gain a “grade or a grave” in the coming fight.

Worth began his march at 2 pm on September 20 with regulars from the 2nd Division, Texas and Louisiana volunteers, and two batteries of horse artillery. The Texas volunteers under Worth included men whose names would be ingrained in Texas folklore: Jack Hays, Samuel Walker, Ben McCulloch, and R.A. Gillespie, among others. The Texans presented a frontier look compared to Taylor’s regulars. Most had long beards and mustaches, wore bright red and blue shirts, and carried a Bowie knife, rifle, and one or two Colt revolvers.

The following day, Worth’s troops met 1,500 Mexican lancers and an unknown number of Mexican infantry who were attempting to block their route to the pass. The Texas volunteers lined up behind a nearby fence, and with support from the light infantry and artillery they repulsed the enemy charge. Worth was now in possession of the Saltillo road, effectively severing the Mexican line of retreat and preventing reinforcements or supplies from entering the city.

Worth’s troops soon discovered a new enemy fort when artillery shells suddenly rained down on them from a location not previously noted in the engineers’ reports. The fort was perched on top of Federation Hill, south of the Saltillo road. A small redoubt sat on the western edge of the hill and a larger fort, El Soldado, guarded the eastern approach. From El Soldado artillerymen could reach Monterrey with their cannons. Worth told his soldiers, “Men, you are to take that hill, and I know you will do it,” to which they responded, “We will!”

Worth sent Captain Charles Smith and 300 infantry, including dismounted Texas volunteers and artillerymen serving as infantry, to attack a redoubt on the western end of the hill. Smith’s men slowly worked their way up the 400-foot hill, grabbing thorn bushes and chaparral to pull themselves up the steep incline. They held their fire until near the top of the hill, then charged pell-mell over the redoubt. The Mexican troops attempted unsuccessfully to throw a nine-pounder gun down the hill, allowing the Americans to turn the cannon on the fleeing Mexicans who were running east toward El Soldado.

Worth ordered Brig. Gen. Persifor Smith, commander of the 2nd Brigade, to support the attack with the 5th U.S. Infantry and the Louisiana volunteers. Smith, knowing that he was not needed at the redoubt, collected the 7th U.S. Infantry and commanded his troops, “Take that other fort!” Each group of soldiers raced toward the fort in an effort to be the first ones there. R.A. Gillespie of the Texas volunteers was the first to enter the fort, followed closely by the 5th Infantry. One soldier from the 5th told the Texans, “Well boys, we liked to have beaten you,” and scrawled upon a captured cannon: “Texas Rangers and 5th Infantry.”

While Worth was conducting his attack, Taylor directed a diversion in the east to prevent Ampudia from fortifying the hills. Taylor ordered Brig. Gen. David Twiggs’s 1st Division, under the command of Lt. Col. John Garland due to Twiggs’s illness, to “make a strong demonstration and carry the enemy’s advanced works, if it could be done without too heavy loss.” Garland, with 800 men from the 1st and 3rd Infantry, along with the Maryland and District of Columbia Battalion under Lt. Col. William Watson, followed Mansfield into the suburbs of the city. The troops marched for roughly 500 yards across the plain, pounded all the while by artillery from the Citadel and La Teneria.

Garland, believing that Mansfield wanted him to attack the fort from the rear, entered the town about 200 yards to the right of the fort. The American troops had not reconnoitered this part of the city and they immediately found themselves in a confusing mix of huts, stone walls, narrow streets, and irrigation canals. They were bombarded by cannons from the La Teneria redoubt, the Citadel, and a new fort they had not yet located, El Rincon del Diablo, which sat to the southwest of La Teneria.

Most of the Maryland and District of Columbia volunteers broke and retreated from the action. The regulars held strong, but were unable to navigate the unknown ground. American soldiers were dropping fast. Captain Braxton Bragg and his horse artillery galloped across the plain through the fire from the Citadel to support the infantry, but the artillery could do no damage against the Mexican fortifications or the troops who hid in doorways, behind buildings, and on roofs. Mansfield suggested retreating, and Garland pulled his troops out of the city. Captain Electus Backus, commanding a company of the 1st Infantry, did not receive the order to retreat. Instead, his men seized a building in the rear of La Teneria, from which point they could fire at the defenders.

Taylor, seeing his regulars retreating, ordered Maj. Gen. William Butler’s 3rd Division of volunteers and the 4th U.S. Infantry to support the attack. Three companies of the 4th Infantry led the advance, including a young lieutenant named Ulysses Grant who had sneaked away from his quartermaster duties to fight with the regiment. The three companies marched directly toward the redoubt, far in advance of the volunteers, and in an instant lost a third of their officers to enemy artillery and musket fire. Grant, who loved horses, was the only soldier on horseback during the charge, but miraculously was not hit. Tennessee and Mississippi troops soon followed, and about 200 yards from the fort an order was given for them to advance and fire. The fire of the volunteers was ineffectual against the redoubt. One soldier noted, “Our little band was fast melting away like frost before the sun.”

Jefferson Davis, colonel of the 1st Mississippi Regiment, could barely be heard over the fire of the artillery when he yelled, “Charge!” The Tennesseans and Mississippians charged directly into the fire from the redoubt. Lt. Col. Alexander McClung of the Mississippi volunteers, perched atop a wall surrounding the fort, waved his sword to encourage the troops. Captain Backus kept up an unrelenting fire from his position to support the attack. Brig. Gen. John Quitman, commander of the Tennessee and Mississippi regiments, led from the front during the charge. He had his horse shot out from under him, and a bullet pierced his hat. The Mexican position in the fort was reinforced by the 3rd Light Infantry Regiment, but the lieutenant colonel in charge of the regiment fled. The Mexican defenders retreated, and Captain Randolph Ridgley turned the captured Mexican artillery against El Diablo. The Tennesseans’ losses accounted for one-fourth of the casualties at the storming, and the regiment thereafter was known as the “Bloody First.”

What had started as a diversion was quickly developing into a full-scale assault against multiple positions in the city. The 1st Ohio, under Brig. Gen. Thomas Hamer, known as “Sledgehammer” to his troops, was ordered to support the diversion by entering Monterrey at a central point. Hamer’s men, much like Garland’s regulars, became lost in the confusing suburbs of north-central Monterrey. One soldier described the movement: “We moved rapidly through a labyrinth of lanes and gardens, without knowing or seeing upon what point of the enemy’s line we were about to strike. At every step discharges from the batteries in front became more deadly.” The troops withdrew at the suggestion of Mansfield.

As soon as Taylor learned that La Teneria had been taken, he ordered Hamer’s volunteers to attack again and assault the recently discovered Rincon del Diablo. The day could be salvaged if the army could take the enemy’s second major fort and gain control of eastern and central Monterrey. The Ohioans crossed the northern suburbs toward El Diablo, fighting in small parties while using houses and walls for cover. Butler and Hamer personally led a charge against the fort, and the Mexicans fled. The Ohioans failed to realize that their right flank was exposed to an artillery battery from a tete du pont, or bridge fortification, which poured grapeshot into the troops. Butler was hit with a musket ball and forced to retire; Hamer became the acting division commander.

The regiment retreated to the plain north of the city, where it was attacked by a group of Mexican lancers. The lancers heartlessly stabbed wounded American soldiers who were strung out in the suburbs and along the plain. Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, who had been accompanying Hamer, organized the Ohioans to repulse the charge by firing en masse from behind a fence. Johnston’s heroic and successful effort led to acclaim from all involved.

Desperate to capture El Diablo, Taylor ordered another group of regulars, including remnants of the 3rd and 4th Infantry, to assault El Diablo from the rear. The troops ended up directly in front of the tete du pont as they sought a way to cross the canal bordering the northern part of the city. The Mexicans were ready and waiting for just such an attempt. One American soldier described the action. “Crossing one street we were exposed in full to the guns of a tete du pont, which commanded the passage of El Puente Purissima,” he wrote. “The fire from it was perfectly awful. We could not proceed any further having arrived at an impassable stream, on the opposite side of which the enemy were in force with three pieces of artillery.” Ridgely arrived with his horse artillery, but his guns were unable to penetrate the parapets of the Mexican defenders. The regular troops retreated to the safety of La Teneria, which was now in the hands of American forces. The action ended the day’s fighting in the east. The Americans still had not captured El Diablo, and Taylor’s “diversion” had resulted in 394 dead and wounded.

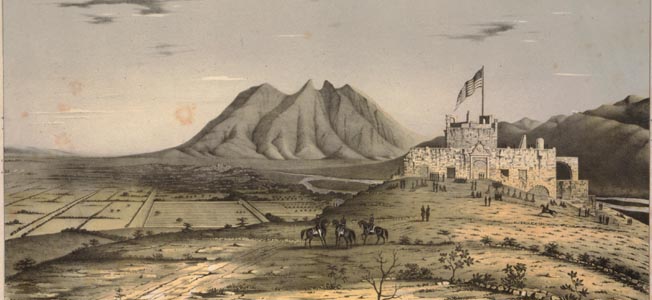

The next day Taylor rested his tattered troops in the east while Worth resumed operations in the west. Worth wanted to attack Independence Hill, where the ornate bishop’s palace was located, to pave the way for an all-out assault on the city. Mexican generals, assuming the 800-foot-high hill was invulnerable, had not properly manned the fortifications. Since the fort’s cannons faced into the city, there was no artillery support for the troops defending the western face of the hill.

At 3 am on September 22, two engineers, Lieutenant George Gordon Meade and Captain John Sanders, led Lt. Col. Thomas Childs and his men to the western base of Independence Hill under a misty cover of fog and rain. Many of the soldiers considered the hill a “forlorn hope” and thought that assaulting the steep hill would be suicide. One observer commented that the soldiers would be “charging upon the clouds.” Childs had three companies of an artillery battalion, 200 dismounted Texas volunteers, and three companies of the 8th U.S. Infantry, which included Meade’s future Civil War nemesis, Lieutenant James Longstreet, commander of Company A. Light rain made the giant crags of rock embedded in the hill slippery and unmanageable. The soldiers, using thorn bushes for leverage, slowly pulled themselves up the difficult slope.

About halfway to the top, they were spotted and fired upon by the Mexican troops in the redoubt. The Americans held their own fire and continued to crawl up the steep slopes while the Texas volunteers fired their rifles at enemy silhouettes atop the hill. The men eventually overran the redoubt, with the indefatigable Gillespie, the Texas Ranger who had been the first man to enter El Soldado, at their head. Gillespie was immediately cut down by the Mexican troops. He was buried at the redoubt, referred to later in official reports as Mount Gillespie.

The Americans fortified themselves in the overrun redoubt and focused their attention on their real prize: the bishop’s palace. From atop the palace waved a giant Mexican flag that could be seen from anywhere in the city. The soldiers knew they would need artillery to assault the palace, but they were unsure that they could transport artillery up an 800-foot slippery mountain. Worth ordered his men to make it happen, and 50 soldiers pulled a 12-pounder howitzer in pieces up the slope and rebuilt it at the redoubt. Soon, the howitzer was firing on the bishop’s palace.

Lieutenant Colonel Francisco de Berra, in charge at the palace, realized quickly that his position was untenable and ordered arriving reinforcements to charge the Americans. Captain J.R. Vinton, anticipating that such a charge was about to take place, ordered his Louisiana volunteers to station themselves in the middle of the hill and feign retreat in the face of the charge. The Texas volunteers and Army regulars hid on both sides of the hill and behind a line of rocks. One of the Louisiana volunteers recalled the harrowing experience: “They advanced on us; we were ordered to close at the right on the top of the hill, and fall back into a ravine one hundred yards distant. We did so in great order. The Mexicans came at us with a yell; the battle grew hot.”

As the Mexicans charged, the Texans and regulars fired into the Mexicans’ flanks. The attackers had limited room to maneuver atop the small hill. Most attempted to retreat toward the palace and into town. The Texans pursued so hotly that they entered the palace before the Mexicans could close the doors. The American troops cleared the palace of the enemy and raised their colors over the structure. Taylor’s troops in the east gave a cheer when they saw the Stars and Stripes flying proudly from atop the palace.

By Wednesday morning, Worth had not received any further communications from Taylor. He decided to attack as soon as he heard Taylor advancing in the eastern part of the city. The previous night, the Mexican troops had retreated from El Diablo to the interior of the city, and Taylor instructed Quitman’s brigade to “advance carefully, as far as he might deem prudent.” Jefferson Davis and his Mississippi and Tennessee volunteers left El Diablo and began advancing into the city that morning. Colonel George Wood’s Texans, assigned to the eastern part of Monterrey, joined the advance.

The Americans were now about to engage in what one soldier termed a “most strange and novel scene of warfare.” Determined not repeat the mistakes of the 21st, the Americans changed tactics. Lieutenant Meade noted, “Had we attempted to advance up the streets, as our poor fellows did previously, all would have been cut to pieces; but we were more skillfully directed.” Grant concurred: “He [Worth] resorted to a better expedient for getting to the plaza—the citadel—than we did on the east. Instead of moving by the open streets, he advanced through the houses, cutting passageways from one to another.” Maj. Gen. James P. Henderson, governor of Texas and commander of all Texas volunteers, directed his soldiers to advance house to house and avoid major streets. Many of the Texas volunteers had fought together at the Battle of Mier four years earlier, when Texas militia forces also proceeded block by block and house by house to assault a Mexican garrison. This was the first battle of the Mexican War for many of the Texans, and they had revenge on their minds. As one soldier noted approvingly, the Texans fought like “unchained lions.”

The Mississippians, Tennesseans, and Texans advanced slowly through the eastern part of the city, using pick axes and crowbars to make holes in the walls of Monterrey’s houses. Once the hole was big enough to climb through, the rest of the party would race across the street and into the house. Ladders were constructed to enable the soldiers to jump from roof to roof. At most cross streets, Mexican artillery belched grapeshot and canister. To advance on a battery, the American troops had to gain the roof of a house and fire down on the battery or encircle it from behind.

Bragg and his artillerymen fought bravely in the city, but they were unable to effect any real damage. Lieutenant George H. Thomas, who served under Bragg and would meet him again at the Battle of Chickamauga in the American Civil War, almost exactly 17 years later, “fired a farewell shot at the foe, and returned under a shower of bullets.” Lieutenant Samuel French, who also served under Bragg at Monterrey, tied ropes to the front and back of his cannons and ordered his artillerymen to load the cannons behind a wall, and then drag them out with the ropes to fire on the enemy.

During the battle, Taylor was in his element. The old frontier soldier never showed doubt or anxiety, even in the hottest situations. On the 23rd, Taylor strolled past a cross street that was undergoing the hottest fire of the day. Mexican artillery fired at any soldiers who appeared in the lane. “Gen. Taylor and staff came down the street on foot, and very imprudently he passed the cross street, escaping many shots fired at him,” a soldier observed. “There he was, almost alone. He tried to enter the store on the corner. The door being locked, he and the Mexican had a confab.” Another soldier, seeing Taylor walk across the dangerous cross street, asked him to retire to a safer area. Taylor responded by directing the soldier, “Take that ax and knock in that door.” The soldier did so, although the owner of the apothecary in question was willing to unlock the door.

Taylor relished playing the role of a captain or major. In the fight in eastern Monterrey on the 21st, Taylor was close on the heels of the volunteers after they stormed La Teneria. There, he ordered Ridgley to fire his artillery at a group of lancers that were counterattacking. Taylor’s bravery under fire stiffened the resolve of his volunteers, many of whom were fighting for the first time in their lives. “His officers and soldiers were not slow to participate in his courageous impulses and resolute spirit,” said one volunteer. When an artillery ball bounced over Taylor’s head on the 19th, word quickly passed down the line that Taylor had not flinched as the ball went past him. When his regulars were routed on the 21st, the volunteer soldiers observed Taylor’s reaction. According to one volunteer: “The tranquil courage of the commanding general was not without influence on our troops. Motionless as an equestrian statue, he occupied the highest point of the hill, his bronzed face turned steadfastly towards the well-known battalions of Regulars, whose courage and discipline were now about to encounter a trial such as they had never known before.”

Worth’s troops moved in two columns into the western part of the city to assault the Mexican forces concentrated at the town’s center. At 4:30 pm, Worth’s troops began meeting stiff resistance, and Taylor, over the objections of many of his soldiers, called off the eastern assault. Ampudia then reinforced his troops in western Monterrey with some of the soldiers who were no longer needed in the east. One of the first embedded military reporters in American history, George Wilkins Kendall, described the fighting: “An incessant rattling of small arms, and a heavy firing of cannon from the barricades of the enemy was kept up from the first; yet above even these the sounds of the pick axe, the crow bar, and the battering ram could be heard as the assailants were slowly but surely working their way to the heart of the enemy’s works. Inch after inch was taken, but not an inch was given.” The Americans soon emplaced artillery capable of reaching the cathedral, where Ampudia and many of Monterrey’s civilians had taken shelter. On the morning of the 24th, Ampudia sent word that he was ready to negotiate a cease-fire. Against great odds, the Americans had won the day.

In all, Taylor lost 120 men killed and 368 wounded at Monterrey. Perhaps the greatest loss was the 16 officers killed during the fight. Many of them had been schooled at West Point and were considered rising stars in the Army. Casualties at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma had been small. Those battles, noted an Army surgeon, were “mere child’s play” compared to Monterrey, the first real test of bravery and leadership—often fatal—for many of the Army’s young officers.

Taylor granted Ampudia a two-month armistice and allowed him and his men to march out of the city with their weapons and one artillery battery. Twenty-five other cannons were left behind. When President Polk heard about the terms, he erupted. Taylor, he said, had no authority to negotiate with the enemy—only to kill him. Old Rough and Ready was forced to contact Santa Anna and rescind the truce. Meanwhile, the president stripped away a large portion of Taylor’s army and sent it to General Winfield Scott, who was preparing an amphibious landing on the Mexican gulf and an audacious cross-country march on the capital city.

In the long run, Polk’s reaction failed to harm Taylor’s rising reputation. In 1848, a few months after the war had ended with an overwhelming American victory, Taylor was elected president on the Whig Party ticket. He did not have long to enjoy the fruits of his Mexican triumphs. In 1850, after only 16 months in office, he died of a sudden and virulent intestinal disorder. Millard Fillmore succeeded him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments