By Robert F. Dorr and Fred L. Borch

Just before it was drawn into World War II, the United States began developing a night fighter version of one of its most famous warplanes. The result was not pretty, but it was practical.

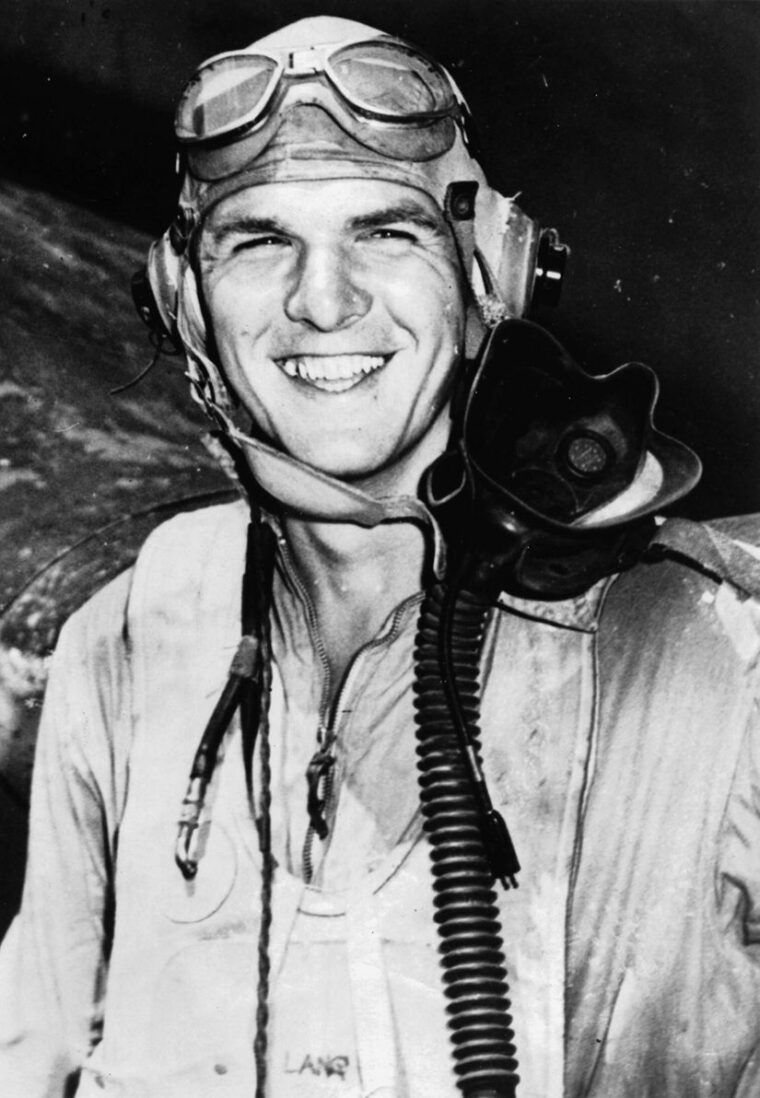

“Before the war, when night arrived, you stowed your planes inside the hangar,” said retired Maj. Gen. Frank C. Lang, who was a first lieutenant when he flew the Vought F4U-2 Corsair. “The invention of radar changed all that. It also gave us a little-known version of the Corsair that at first looked a little odd.”

Lang, who sat for a series of interviews for this article before he died at age 90 on December 29, 2008, was one of a handful of Marine Corps fighter pilots who flew the almost unknown “dash two” version of the Corsair, which had a thimble-shaped radome (radar dome) on the leading edge of its starboard wing. “Before the war I had never even heard of this invention,” said Lang.

The term “radar” was an abbreviation for “radio detecting and ranging.” In 1922, A. Hoyt Taylor and Leo C. Young at the Navy’s Aircraft Radio Laboratory in Washington, D.C., were experimenting with radio transmissions between their station and a receiver located across the Anacostia River. During the test, a passing river steamer interrupted their signal. This suggested that radio waves might be used to detect the passage of a ship at night or in fog.

In 1936, R.C. Guthrie and R.M. Page of the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington tested a radar unit that could detect an aircraft 25 miles away. In 1940, the Navy and the Sperry Company developed an air-to-air radar unit that could be carried by a fighter.

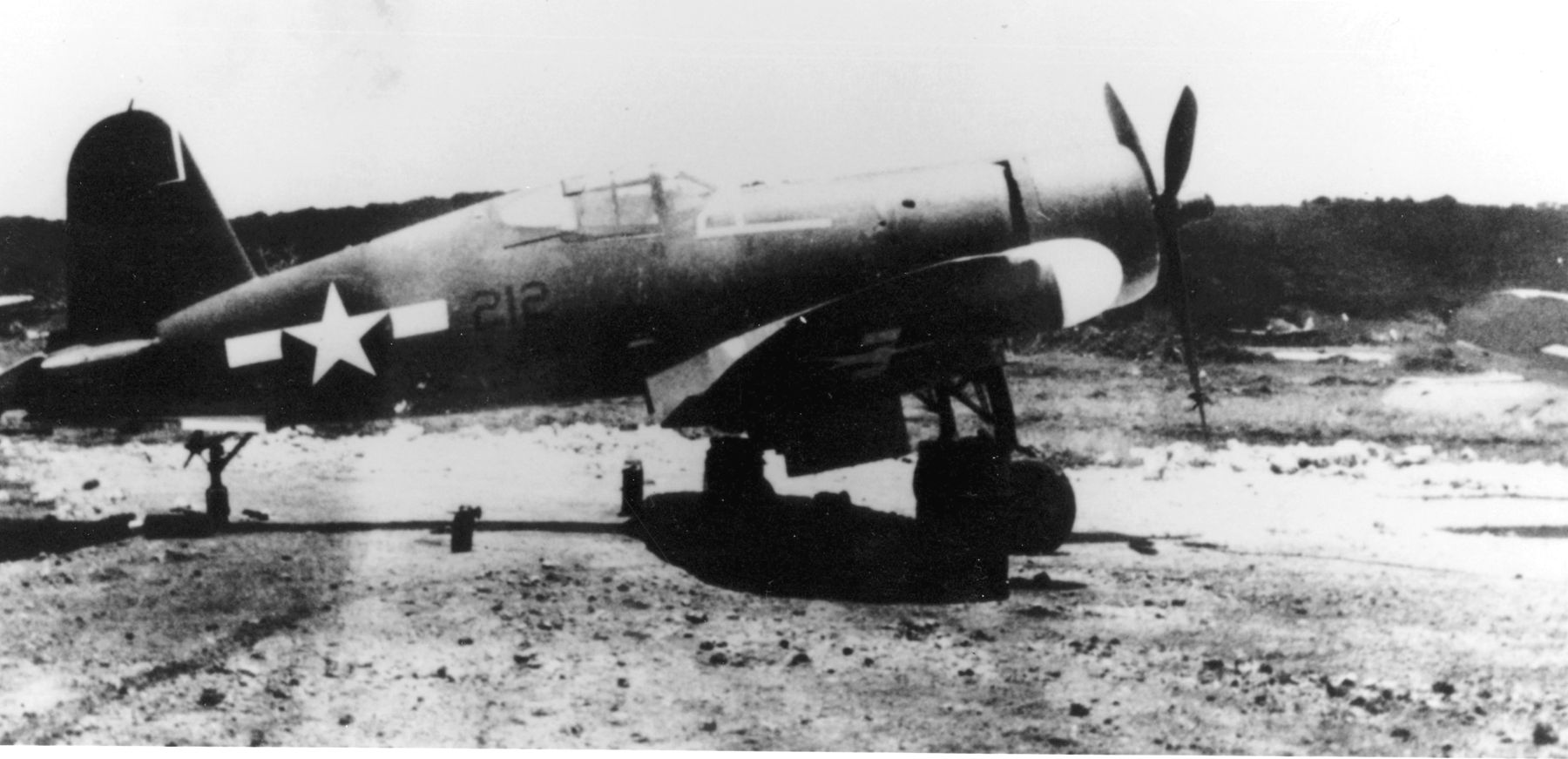

Just after Pearl Harbor, the Naval Aircraft Factory at Philadelphia began fitting 34 F4U-1 Corsair fighters with an APS-4 radar using an 18-inch parabolic antenna inside a housing on the leading edge of the right wing of each aircraft. Because of the radar pod, the planes’ armament was reduced from six wing-mounted .50-caliber machine guns to five.

With these changes, plus a small radarscope on the pilot’s instrument panel and flame dampeners to conceal exhaust emissions during the hours of darkness, the planes became F4U-2 models. Later, two more were modified. Just 36 of the little-known F4U-2 night fighters were built. Had the Navy’s own designation system been properly used, they would have been called F4U-2N models, but the term was not used.

“Believe it or not, having that fat radar installation out on the right wing actually improved the performance of the Corsair, so that the F4U-2 was in some ways easier to fly than the early F4U-1,” said Lang. “The radome improved the stall characteristics considerably. There was a noteworthy improvement in left roll performance over the standard F4U-1.”

Fighting at night was a new idea. “Marine night fighters got started at the beginning of 1943,” said Lang. “I came out of flight school and went directly into night fighters at Cherry Point, North Carolina. Our first commander at squadron VMF (N)-532 was Major Ross Mickey. We received 18 of the 36 F4U-2 Corsairs made, while the Navy got the others to equip squadrons VF (N)-75 and VF (N)-76. VMF (N)-532 became the first outfit to shoot down an enemy aircraft at night using night fighting equipment.

“Our second commander, Major Everette H. Vaughan, was a guiding force in developing tactics and methods for taking advantage of the superb performance of the radar-equipped Corsair,” said Lang. Vaughan arrived at Cherry Point in the spring of 1943. He was an experienced pilot who had flown in the reserves before the war. He had been an airline pilot at the time of Pearl Harbor.

He was “a real leader who rarely needed to use his powerful personality,” said Lang.

The squadron’s F4U-2 fighters had the distinctive, metal-brace canopy unique to early Corsairs and the APS-4 radar housed inside a dome on the right wing. Those first Corsairs really were not safe airplanes, as Lang recalled. They had a tendency to stall out unexpectedly. Marines overcame deficiencies by simply learning how to deal with the F4U-2’s handling characteristics.

Lang, born in 1918 in New Rochelle, New York, worked for United Aircraft, the parent company of Corsair maker Vought, before the war and earned a private pilot’s license. As a Marine, he found plenty of positive things to say about the Corsair, which had a roomy and comfortable cockpit.

“I’m a big guy, and I had lots of room in the cockpit,” said Lang. “I had no difficulty whatever reaching the levers and buttons. The legroom was just fantastic in the Corsair. They had a hole in the bottom of the fuselage with a piece of Plexiglas there that you could look through. We had one gent in our squadron, 1st Lieutenant Don Fenton, who just made it into the service because he was five-foot-four-and-a-half. He had to use a pillow to fly the Corsair.”

Flying in the tropical climes of the South Pacific, Lang said, “we wore just a flight suit with a pair of shorts underneath. It was pretty warm out there. We had our flying helmet with oxygen mask. We always put our oxygen mask on immediately on taking off.”

Lang and his squadron arrived at Tarawa on January 13, 1944. A month later, the squadron moved up to Roi-Namur, part of Kwajalein atoll in the Marshall Islands, where night intruder flights by Japanese bombers were a pesky and persistent problem. The Japanese were flying over Eniwetok atoll, and that is where VMF (N)-532 got its first kill, on April 14, 1944, when First Lieutenant Edward A. Sovik and Captain Howard W. Bollman each shot down a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber off Engebi Island, Eniwetok atoll.

These were important victories, but the cost was high. First Lieutenant Joel E. “Pete” Bonner scored hits on another “Betty” but sustained damage and had to bail out. First Lieutenant Donald A. Spatz was given an incorrect vector by ground controllers and went down in the ocean. A Navy destroyer eventually rescued Bonner, but Spatz was never seen again.

In an official report, Bollman described a night battle of a kind that had not taken place previously: “I’d just returned to my tent after flying combat air patrol from 2100-2400 and was getting ready to hit the sack when the command car driver came to pick up First Lieutenant Frank C. Lang. He told me that there was to be an alert. I rode to the line with Lang, not intending to fly but to help out on the ground. As we arrived at the flight line, Spatz took off (0025). Lang took off shortly afterward.

“The sirens sounded. The duty phone rang requesting another fighter. I ran out and scrambled in F4U-2 number 212 at about 0045, just in time to hear Bonner announce that he was ready to jump. I tested my gun after takeoff….

“I was vectored 270 degrees to Angels 20 [20,000 feet]. When I had reached 20 miles from base, I orbited once in my climb and reached Angels 20 immediately. As soon as I reported ‘level,’ I was given a customer, ‘Vector 260.’ A minute later, I picked up a contact at three and one-half miles ahead. It soon became obvious that we were on opposite courses, and at about two miles I commenced a hard starboard, 180-degree turn, informing controllers of my action. I turned a bit past 180 to get back on my original track and immediately picked up the bogey at two and a half miles, azimuth 30 left above.”

Bollman’s account does not say much about how he was stalking his adversary using air-to-air radar, peering down at the tiny scope in his cockpit. No Marine had ever located and attacked an enemy aircraft this way. Bollman slipped behind the “Betty” and was now in position to chase it.

“I closed rapidly to half a mile,” Bollman wrote. “I slowed to the speed of the target to plan my attack. There was a white cloud base below, and I had no desire to be seen against it. The moon was between two o’clock and 15-20 degrees elevation and me. I played with the idea of getting above the target so as to see him against the clouds but was afraid he might be lost under a wing or nose of my plane so I decided to come in at his altitude and 5 or 10 degrees on his down-moon side.

“I added speed and crept up. At 300 yards, I looked up and saw the target exactly where he should have been—a twin-engined ‘Betty’ bomber.

“I immediately speeded up and closed very rapidly. I opened fire at 150 feet dead astern and 15 feet below, aiming at his right wing root.

“I was startled by the lack of tracers. I felt my bullets were going astray. I fired for less than two seconds, but his starboard engine began smoking. I then transferred my aim to the port side and after another two-second burst, I observed flame and smoke on his port engine.

“At first, I mistook white flashes from my incendiaries to be return fire. I instinctively ducked behind my engine. But I wasn’t receiving return fire.

“The target was now in a 15-degree nose-down attitude. I nearly rammed him. Employing what might be termed an outside snap roll to avoid him, I pulled around to one side and above to observe. Now, it appeared the flames had blown out, so I gave him another burst from 20 degrees above and astern at 100 yards. Fifteen seconds later, he broke into two pieces and dropped in flames. At the time of the explosion, there were lights, which might have been flares or ‘gizmos’ [pieces of aluminum, or chaff, that the Japanese released from their aircraft as a decoy] dropped from the ‘Betty.’ I looked at my watch. It was about 0110, or 20 minutes after takeoff.”

First Lieutenant Frank C. Lang’s memory of that action came out in an interview for this article: “While Bollman and Sovik shot down Japanese bombers, I was flying around and my radar was picking up fake returns, or ‘gizmos.’

“Pete Bonner, who later became an assistant secretary of the Army, was too close to his ‘Betty’ bomber when he opened fire. When Bonner fired tracers, the tail gunner in the bomber saw him and shot out Bonner’s engine. So he had to bail out.

“We spent a day looking for him. But it wasn’t until a day and a half later that a B-25 Mitchell bomber spotted Pete in the water. A destroyer later rescued him. He was a man of very light complexion. He had no cover to protect him from the sun. After two days in that raft, he had blisters all over his body. We thought we were going to lose him for a while. Our doc did some miraculous things to treat him. We later made some modifications to the life raft based on his experience.”

That same night, the squadron lost pilot Spatz. “The radar controller lost Don,” said Lang. “The controller gave Don two vectors and then forgot what vector he’d given him. I was the last contact with Don. I was up at about 25 or 30,000 feet. His engine gave out. I tried to tell Don to bail out, but he wouldn’t. So he went in.”

As the war progressed, VMF (N)-532 moved up to Saipan in the Marianas Islands. At this point in the war, the squadron saw less night activity, although the presence of F4U-2 night fighters was a deterrent to the Japanese.

“I know we deterred them from operating effectively at night because as soon as we left they came out in swarms,” said Lang. “They had to put Army Air Corps Northrop P-61 Black Widows in there to fight them at night. The P-61 wasn’t available when we were doing our night work.”

In July 1944, VMF (N)-532 flew from Saipan down to Guam to cover the invasion there so the fleet could have night fighter protection. The carriers in the fleet did not want to work their crews both day and night. For the night missions, Lang and his fellow Marines took off from Saipan, flew down to Guam, spent about an hour and a half providing coverage over the fleet, and then flew back to Saipan.

“This was one time when we really got a sense for the sheer magnitude of a Pacific island invasion. On a moonlit night, we could see vast numbers of our warships and troop ships at sea,” said Lang. “On rare occasion, we could glimpse flashes from shooting. There was no doubt that our side was advancing across the Pacific and moving closer to Japan.”

Robert F. Dorr is a U.S. Air Force veteran, a retired diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, A Look at Presidential Aircraft and Air Travel. Fred Borch is a retired U.S. Army officer and currently serves as historian of the Judge Advocate School in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is the author of the book Kimmel, Short and Pearl Harbor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments