By Louis Kraft

In 1856 a young Philadelphian named Edward W. Wynkoop—Ned to his friends—migrated to Kansas to find his fortune. When gold was discovered at the base of the Rocky Mountains two years later, he joined one of the first mining outfits to set out for what is now the state of Colorado. Not a successful miner, Wynkoop made most of his money during these early years tending bar. On the wild side and good with guns, it did not take long before he gained notoriety in the booming town of Denver. One newspaper labeled him “a bad man from Kansas, who wore buckskin breeches and carried a Bowie-knife and revolver in his belt.”

Like many people who went a-westering at that time, Wynkoop harbored the typical prejudices of the frontier—mainly that Native Americans were little more than wild beasts fit only to kill. His opinion would change in the not-too-distant future. Three events made this possible. The first two happened in quick succession: In July 1861, after the outbreak of the Civil War, he enlisted as an officer in the First Colorado Volunteers; a month later he married Louise Wakely. She gave him stability, while the responsibility of military leadership gave him maturity.

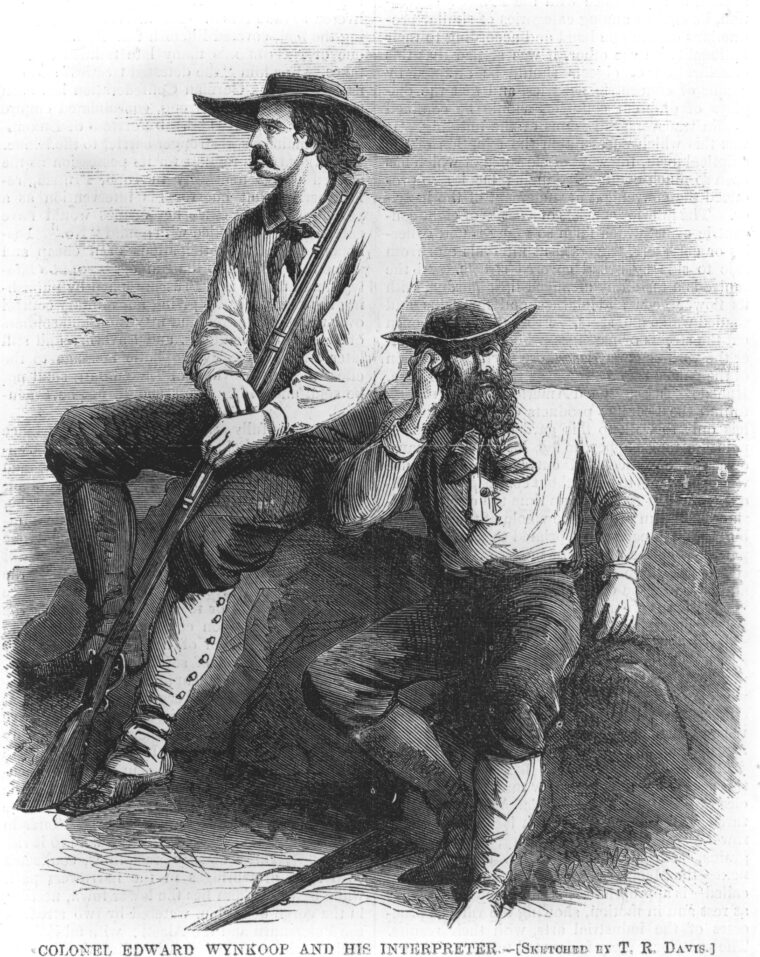

The third event did not happen until 1864. That fall, the Southern Cheyennes and their allies terrorized Colorado Territory. By that time Wynkoop was a major. Although his orders were to kill all Indians on sight, he was holed up at Fort Lyon in southeast Colorado Territory. When native messengers brought an offer to talk peace, Wynkoop decided to risk death and meet the warring chieftains. On September 11, he and his detachment of 127 men were confronted by a battle line of six hundred painted warriors at the Bend of Timbers. It looked as if he had made the blunder of a lifetime.

Instead, Cheyenne chieftain Black Kettle appeared and prevented violence. The next day would be the first day of Wynkoop’s new life. Although all his efforts to bring peace to the land would end in disaster two-and-a-half months later when a joint Cheyenne-Arapaho village was attacked and destroyed at Sand Creek, his metamorphosis was complete.

He no longer viewed Native Americans as less than human. For the rest of the decade his name would be linked with the Southern Cheyennes, first as a special agent on detached duty from the military and then as a U.S. Indian Agent of the Upper Arkansas agency, which eventually headquartered at Fort Larned, Kansas. His wards included the Plains Apaches (sometimes called the Kiowa Apaches), the Arapaho, and the Southern Cheyennes, who named him the “Tall Chief” because of his height.

The Southern Cheyennes call themselves the Tsistsistas, which can be translated to mean “the people,” “our people,” “people alike,” or possibly “related to one another,” or “similarly bred.” Sometimes their name has been translated as “gashed” or “cut people.” The white man came up with the word “Cheyenne” from the Lakota word, “Shai ena,” which translates to “people who speak with a strange tongue.”

Wynkoop constantly found himself in a sort of no man’s land. As a U.S. Indian Agent, he walked a lonely trail. Although many Tsistsistas respected and appreciated his efforts on their behalf, there were just as many who blamed him for all the wrongs heaped upon their people by the ve-ho-e—the white man. Some whites were also grateful for Wynkoop’s efforts to bring peace to the land, while others viewed him with a jaundiced eye. They blamed him for supplying the natives with weapons so they could again ride the war trail, or dismissed him as little more than a thief lining his pockets with money from goods that somehow never reached the Native Americans for whom they were intended.

“Peace or War”

War dominated the central and southern plains after the tragedy at Sand Creek. But by the end of 1866, racial conflict had diminished. Wynkoop received some credit for helping bring about the reduction in violence. But, as in past years, the word “peace” was not synonymous with the words “no violence.” Although Wynkoop would have us believe that all was quiet on the frontier at the beginning of 1867, race relations remained strained as white encroachment continued.

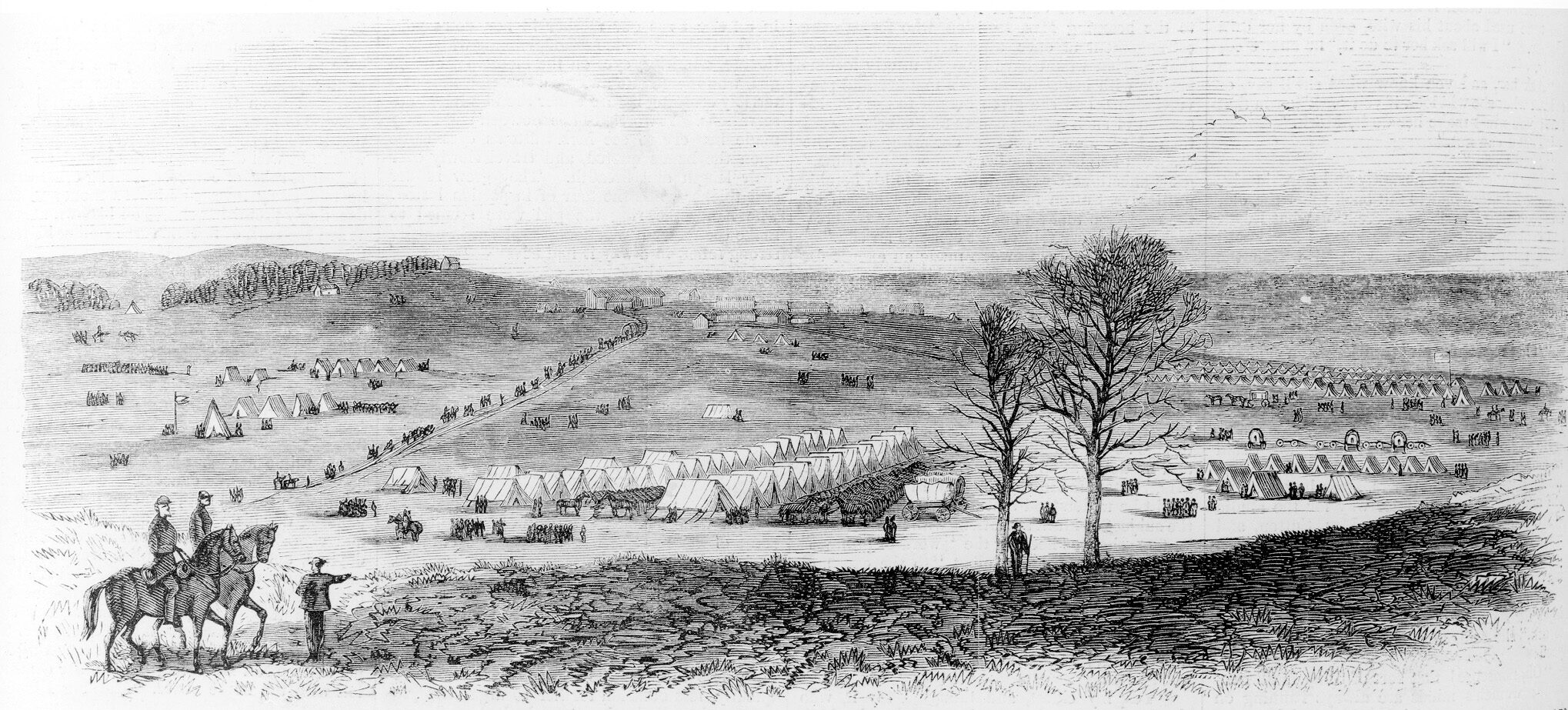

The year 1867 was when the U.S. government decided that it was time to secure the plains for both white migration and the laying of railroad track. That spring, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, hero at Gettysburg and now commander of the Department of the Missouri, organized an expedition to meet with leaders from the various tribes. His goal: Impress the migrant natives with U.S. power.

On March 13, the general wrote Wynkoop:

“My object in making an expedition at this time is to show the Indians within the limits of this department that we are able to chastise any tribes who may molest people who are traveling across the plains. It is not our desire to bring on difficulties with the Indians, but to treat them with justice and according to our treaty stipulations, and I desire especially in my dealings with them to act through their agents as far as possible.”

This last phrase was little more than lip service. Although the general claimed that he intended to heed the advice of those knowledgeable in Indian ways, he had no intention of doing so. When asked for his impression of Indian agents that year, Hancock first replied, “I do not know about Wynkoop,” then went on to categorize all Indian agents as little more than untrustworthy people out to get rich. Although Hancock did not specifically place Wynkoop in the same category as his peers, he did harbor a prejudiced view of the Cheyenne agent.

In that same March 13 letter to Wynkoop, Hancock wrote: “and tell them also, if you please, that I go fully prepared for peace or war.” The words “peace or war” are key to what followed. Actions speak louder than words, and Hancock defeated any peaceful intentions he had as soon as he assembled his massive force of 1,400 men.

A Meeting with the Dog Soldiers

To make the arrangements, Wynkoop sent interpreter Edmund Guerrier and guide F.F. Jones to invite the Tsistsistas and Dog Soldier leaders to meet with Hancock at Fort Larned on April 10. The Dog Soldiers had begun as one of the six Cheyenne military societies, but in 1856 they broke away from the southern band, creating three distinct divisions within the tribe, which also included the Northern Cheyennes. Roaming along the Smoky Hill and Republican rivers, they acted as a base for any warrior willing to fight white aggression. Dog Soldier chieftain Bull Bear sent word back to the Tall Chief that he and others would attend the council.

Two days before the two sides were to meet, a hard wind blew from the north and a furious snow pelted the earth, effectively stopping all travel. Although Hancock, who was now camped near Fort Larned, was forced to wait out the storm on the 9th, he still expected Wynkoop’s wards to appear at Larned on the 10th. They did not. Instead, they sent runners to tell the Tall Chief that their ponies were too weak to travel through the snowdrifts. Wynkoop informed Hancock and the council was put on hold until better weather. However, the next day new runners informed Wynkoop that the native leaders were about to leave their village on Red Arm Creek—Pawnee Fork to the whites—and begin the journey to Larned, but had been sidetracked by a herd of buffalo, which they now hunted. This update did not please Hancock. On the 12th, the general announced he would leave the next day for the native encampment.

That night Dog Soldier leaders Tall Bull, White Horse and Bull Bear, along with Tsistsistas chieftain Little Robe and some 10 or 12 others, including Oglala Sioux chieftain Pawnee Killer, appeared at Larned. Worn out, the Indians asked for food. Hancock was agreeable to feeding them, and a meal was served in a tent. But Hancock insisted they meet that night. As peace councils always took place during the day, the chieftains immediately became wary.

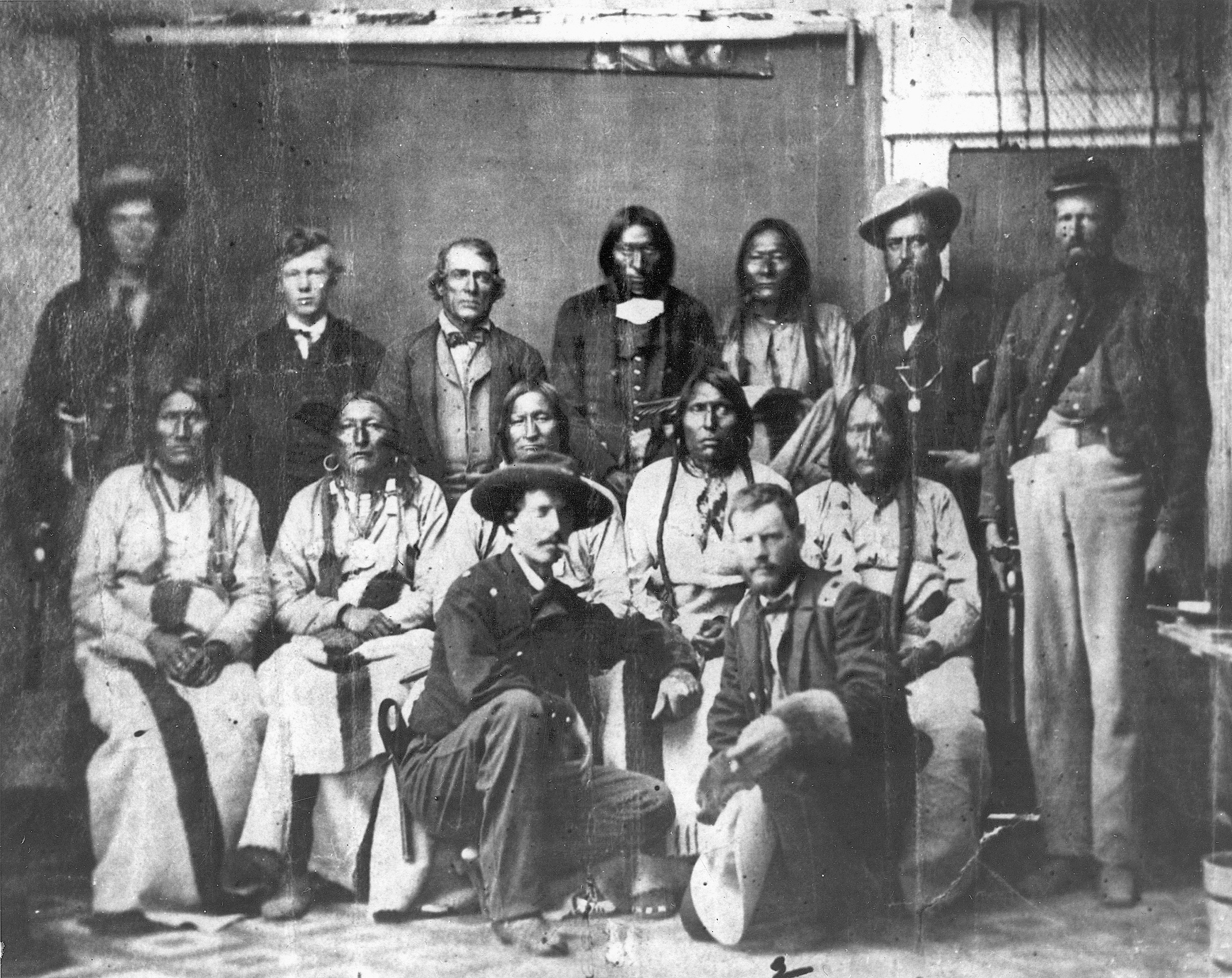

After eating, Wynkoop and Guerrier accompanied the native leaders to a huge bonfire Hancock had lighted for the council. They sat with the Indians while Hancock and his officers sat on the opposite side of the dancing flames. One of the chiefs lit a pipe, inhaled four sacred mouthfuls, and passed the pipe on to the next person. Everyone would share the pipe before the council could begin.

Premonitions of Wynkoop and Leavenworth

Afterward, Hancock began matters. He said: “We [a]re not [here] to make war, but [a]re ready … to fight any Indians who [wish] for war.” He then informed the native leaders that he intended to visit their village. Tall Bull said: “[My] tribe [is] at peace, and [wish] to remain so; [we] hope [you] would not go to [our] village, as [you] could not have any more to say to [us] there than [here],” to which Hancock replied: “[I am] going to see [you] at [your] village on the morrow.”

The council over, Tall Bull took the Tall Chief aside and asked him to talk Hancock out of moving toward the village. Wynkoop approached Hancock sometime after midnight and restated the request. Hancock refused. He intended to march at 7 that morning and, as all his officers knew, he would “talk war or peace to them, as they may elect.”

This exchange characterized the Wynkoop-Hancock relationship. One was in the position to advise but the other refused to listen.

As planned, Hancock moved toward the Indian encampment the next morning. Wynkoop wrote his superiors: “I accompanied the column for the purpose of subserving the interests of my department by looking after the interests of the Indians of my agency as far as lay in my power.” Kiowa-Comanche agent Jesse Leavenworth also accompanied the column.

During the march a number of Tsistsistas joined the caravan and rode with the Tall Chief. Wynkoop remembered how they exhibited, “in various ways their fear of the result of the expedition—not fearful of their own lives or liberty, … but fearful of the panic which they expected to be created among their women and children upon the arrival of the troops.” After traveling a little over 21 miles, Hancock halted. To his front, Indians had set the prairie on fire. The general immediately crossed the Pawnee River and continued the march, camping 23 miles from Larned.

That afternoon (April 13) Pawnee Killer, with several Lakota, rode into the white bivouac. The Oglala announced that he camped with his brothers, the Tsistsistas. Soon after, White Horse and some of his brethren rode into the white camp. It was arranged that the Indians would spend the night and the other chiefs would arrive early the next morning for the conference.

Wynkoop was not the only white man who was aware of how ticklish the situation could become. Agent Leavenworth also knew what could soon happen, mainly that the closer the column got to the native camp, the more frightened the villagers would become. And this was true. Already the women and children began to cry and worry. Everyone in the village knew what had happened at Sand Creek. The warriors were just as nervous as their loved ones. Had not the soldier chief presented a militant attitude and threatened the chieftains at Fort Larned? And now he marched his army toward their village. The prairie fire had not stopped him. Most likely nothing would stop him.

Early on the morning of April 14 Pawnee Killer rode out of the white camp. Supposedly, he would hurry his comrades to the meeting with the general. But Pawnee Killer did not return, and the Indian leaders did not appear. Then about 9:30 am, Bull Bear rode into the white bivouac and stated that the Indian leaders were on their way.

Ignoring Winkoop’s Advice

By this time Hancock’s patience had grown thin. In this, he was not alone. Wynkoop had also lost his patience. The Tall Chief had had Hancock’s promise that he would “defer to me certain matters connected with the Indians of my agency.” Wynkoop was supposedly the expert on the Cheyennes, and yet Hancock constantly turned his back on him. The Tall Chief’s attitude, bolstered by frustration, did not go unnoticed. Reporter Henry Stanley, referring to both Wynkoop and Leavenworth, wrote: “The General commanding has been very kind and courteous to the agents, but everything that he has done, so far, has been met by them with acrimonious censure.” By this time Wynkoop did not care what anyone thought of him. He had no intention of backing off and again informed Hancock that he should not move too close to the village.

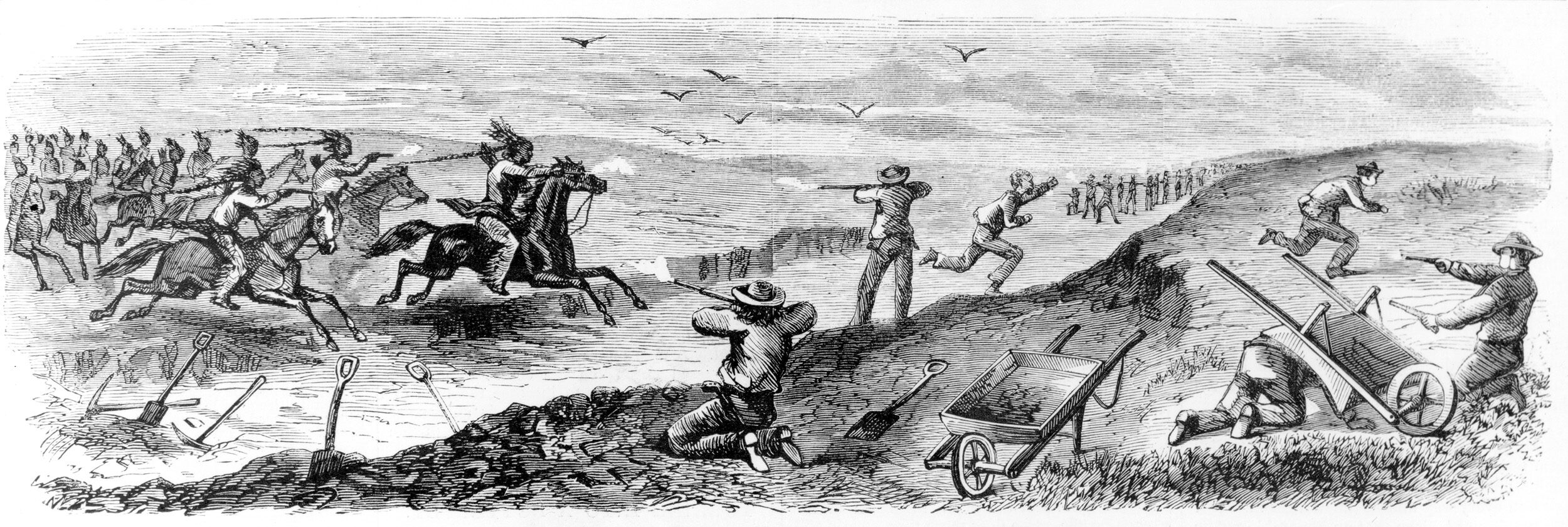

And Hancock once again refused to listen. Shortly after 11 am, the general and his army resumed their journey toward the as-yet-unseen Indian village. Captain Albert Barnitz (7th U.S. Cavalry) wrote that the command moved in “order of battle—Infantry in line, cavalry in ‘close column’ on the flanks, and trains in three columns in the center.”

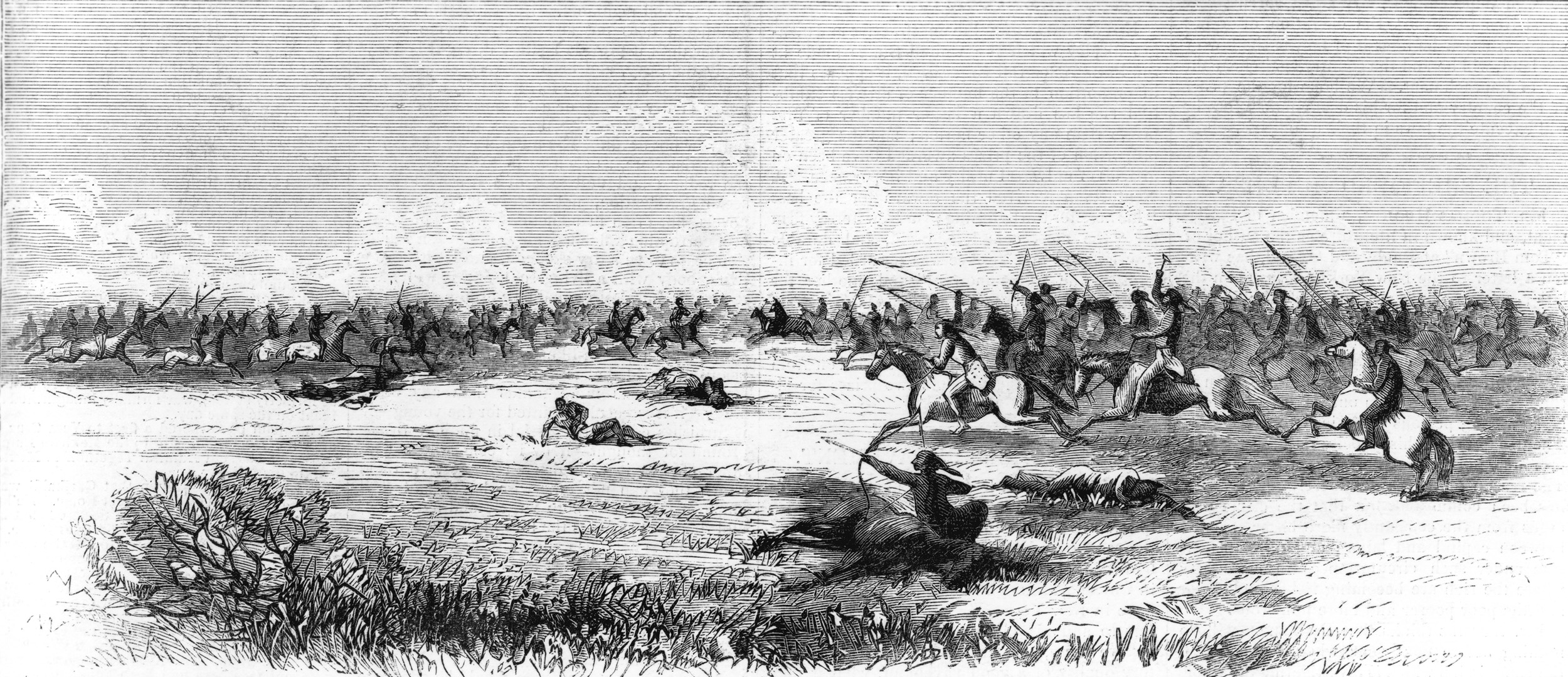

A cold wind raked the land. By noontime, after traveling only a short distance, they climbed a small hill. Suddenly a massive throng of warriors appeared in the valley below. Estimates put the native numbers somewhere around three hundred. “[S]ome of them gaily dressed,” Barnitz recorded, “with flaming red toggery and scarlet blankets, displaying their burnished lances.”

The infantry and artillery quickly formed a line. The cavalry drew sabers and rushed forward. Hancock’s army was nervous, anxious and … eager. Wynkoop took in his surroundings, later commenting: “The whole command presented such an appearance as I have seen just prior to the opening of an engagement.”

The Indians must have had the same impression; they halted their advance—their ponies dancing in place. It was obvious that they were “disturbed” by the appearance of the soldiers. Fully expecting the ve-ho-e to push forward, chieftains rode across their line yelling for everyone to stand firm and prevent the soldiers from reaching the village and killing the women and children. The angry horde waved its weapons in the air, shouting.

Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer (7th U.S. Cavalry) saw this painted, feathered and very formidable foe for the first time. This was not Poor Lo’, whom he had read about in the newspapers, nor was it the noble savage of the James Fenimore Cooper novels. He later claimed: “We witnessed one of the finest and most imposing military displays, prepared according to the Indian art of war, which it has ever been my lot to behold. It was nothing more nor less than an Indian line of battle drawn directly across our line of march; as if to say: thus far and no farther.”

A Last Effort to Prevent War

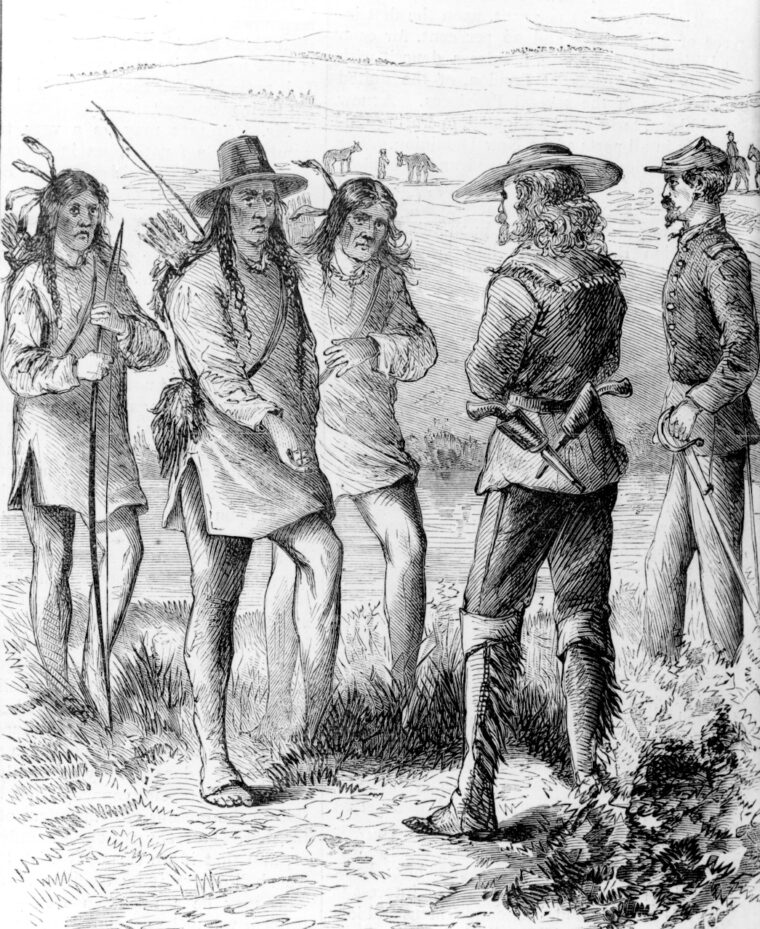

Wynkoop must have remembered his own battle line at the Bend of Timbers in ’64. Black Kettle had prevented violence that day. But his old friend was not here this day. Instead of facing a peace chief, Wynkoop knew the white army faced Tall Bull, Bull Bear and the famed Tsistsistas warrior Roman Nose. An explosion seemed a heartbeat away. Knowing he had to act quickly, Wynkoop rode to Hancock and requested permission to ride between the lines. He felt that if the Cheyennes knew he was present, it would ease their fear. Permission granted, Wynkoop took Guerrier and rode into the valley and toward the native line.

Some of the Tsistsistas leaders were overjoyed when they recognized the Tall Chief riding toward them. They dashed forward, surrounding him a couple of hundred yards from the white line. The Cheyennes expressed “their delight at seeing me there,” Wynkoop reported, “saying that now they knew everything was all right, and they would not be harmed.”

Wynkoop’s act was not risk free. The Indians were angry and suspicious. Some trusted his word; others did not. Although Black Kettle had absolved him from any wrongdoing in 1864, he knew others still blamed him for the destruction of the village. As the half-Indian George Bent said: “Most of the Cheyennes were very bitter against the whites on account of the treachery at Sand Creek.” There had to be an unsaid question on every warrior’s mind: Did the Tall Chief bring the troops to destroy their village?

Then Wynkoop saw Roman Nose, who was dressed in an officer’s uniform and wearing a trailing war bonnet. The warrior rode back and forth in front of the native line, screaming at them to fight. Wynkoop, again with Guerrier, galloped to Roman Nose. He asked him to keep his warriors steady, that no one would be harmed.

While Wynkoop was with Roman Nose, Bull Bear, who had remained with the soldiers, rode up to the gathering of chieftains. Like the Tall Chief, he told the head men that everything would be fine. At this point, they warned Bull Bear that Roman Nose had threatened to kill the soldier chief.

The Stubborn Hancock

Wynkoop and Guerrier, with Roman Nose in tow, rejoined the group of head men. Then, with Roman Nose carrying a white flag, Wynkoop and Guerrier led Bull Bear, Pawnee Killer and nine other native leaders toward the white line. Hancock and several other officers rode out to meet them.

Well armed, the Indians carried arrows and strung bows. Roman Nose supposedly had four revolvers, a Spencer carbine, as well as his bow and arrows. Hancock began matters by stating that if the Indians came to fight, he was ready to commence. Roman Nose replied that if he came to fight, he would not have come this close to the soldier guns. Then Roman Nose reached out, touched the soldier chief’s face and counted coup, that is, won a distinction for touching an enemy’s face. He turned to Bull Bear and told him to return to the warrior line. He did not want him to die when he killed the soldier chief. Bull Bear immediately grabbed the bridle of Roman Nose’s pony and led him from the group. Bull Bear did this not to protect his friend, but to prevent his people from being massacred if Roman Nose carried out his threat.

Apparently Hancock did not realize what had happened for he did not comment on it. He did complain about talking in the wind, then stated he intended to move closer to the village. He invited the leaders to talk again that evening after he pitched camp. Although the Indians did not want to talk at night, they acquiesced to the soldier chief’s request, as they did not want to fight.

The meeting over, the Tsistsistas and Lakota moved quickly toward their village, while Hancock resumed his march. Bull Bear, Wynkoop and Guerrier rode together. Bull Bear told Guerrier to tell Wynkoop he did not want the soldiers too close to the village. During one of the halts, Wynkoop approached Hancock and repeated Bull Bear’s message. He then added: “I [fear] the result [will] be the flight of the women and children.”

Hancock refused to alter his goal. That afternoon, after traveling another seven miles, the military set up camp on Pawnee Fork one mile from the village. “[O]n our left the wooded stream,” Barnitz wrote, “beyond which at the distance of a mile or two are the bluffs—on our right a mile or two off, rolling swells of the prairie, and on our right front, by a little belt of timber, is the Indian [Cheyenne] encampment.” The village consisted of 132 Cheyenne lodges and 140 Sioux lodges.

Abandoning the Village

The panic that had begun earlier in the village reached fever pitch. Women screamed while they frantically packed their ponies. Then, as Wynkoop predicted, the women grabbed their little ones and fled. When word of the massive exodus reached Hancock, he sent for the native leaders. Tall Bull, Bull Bear and Roman Nose, among others, appeared. The general asked why the women and children ran. Roman Nose, in turn, asked if ve-ho-e women and children were more timid than the men. He then queried the soldier chief about Sand Creek.

Hancock ignored the warrior. Instead, he demanded that the principal men catch their women and children, and that “he considered [the leaving] an act of treachery.” As it turned out, the Lakota had also begun to desert the village. Bull Bear and Roman Nose refused to do this. However, three other Tsistsistas volunteered to go after their fleeing women and children; two of these would ride borrowed army horses, because theirs were too weak to travel.

A waiting game began. Wynkoop and everyone else sat around wondering what would happen next. Then, at about 11 pm, Guerrier, who was half-Cheyenne and who perhaps dragged his feet before going back to the white bivouac, returned the borrowed horses. The chiefs had failed to catch the women and children. He reported that Tsistsistas warriors were now deserting the village.

Hancock ordered Custer to surround and take the village. He then sent for Wynkoop. After updating him on the latest developments, he asked the agent what he thought of Custer’s orders. Wynkoop said: “[I]f there [a]re only two men found there, when they s[ee] the cavalry they would have a fight.” Hancock replied: “It matter[s] not.”

Soon after, Custer surrounded and then cautiously entered what turned out to be an empty village. The Indians’ haste to depart was evident everywhere. Reporter Stanley wrote: “Dogs half eaten up, untanned buffalo robes, axes, pots, kettles, and pans, beads and gaudy finery, lately killed buffalo, and stews … cooked in … kettles, [everything] scattered about promiscuously, strewing the ground.”

Depending upon which report you read, Custer found the following people in the village: (1) A girl between eight and twelve, who might have been blind in one eye. She was either white, mixed or Cheyenne. She may or may not have been an idiot; she definitely had been raped. If she had been raped as many times as some of the reports claim, this might account for her incomprehensible babbling. (2) An old Lakota man with a broken leg. In some reports, his wife remained with him. (3) White Horse’s mother, who was demented.

“Fear Alone”

After becoming aware that most reports stated the little girl was white and had been raped by Native Americans, a livid Wynkoop would later write Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas Murphy: “That she was white is false, that she was ravished is correct. She was found after the camp was occupied by the troops, and the question in my mind is still, by whom was this outrage committed? If by her own race, it is the first instance I have any knowledge of.”

Wynkoop did not sleep that night; instead he kept after Hancock, “exerting himself all he [could] in the line of his duty.” About 2 am the general stated “that he intended to burn the village [the] next morning, as he considered [the Indians] had acted treacherously towards him, and they deserved punishment.”

Wynkoop made it plain to Hancock that he believed “it would have a bad effect upon the Indians generally … and that the burning would probably cause other tribes whom we wish to see to fly from us.” After asking Hancock not to burn the village, Wynkoop continued: “I am fully convinced that the result would be an Indian outbreak of the most serious nature; while, at the same time, there is no evidence, in my judgement, that this band of Cheyennes are deserving this severe punishment.”

When Hancock would not comment on what he would do, Wynkoop tried another approach, telling the general that the Cheyennes ran because of “fear alone, … Your movement toward the village terrified them.”

The Tall Chief fought a losing battle, and he knew it. Next, he urged Col. A.J. Smith (7th U.S. Cavalry) to stop Hancock from burning the village. Smith agreed with him and said he would do what he could. Retiring to his tent, Wynkoop wrote a protest letter to Hancock. After outlining the events of the day, along with his opinion on the course Hancock should follow, he predicted another war if the general ignored his advice. Next, Wynkoop wrote Commissioner of Indian Affairs N.G. Taylor, predicting war coming to the Plains.

Escalation of the Conflict

Custer’s pursuit of the fleeing Indians proved fruitless as the Native Americans split into small groups and scattered across the prairie. During the evening on April 16, Custer echoed Agent Wynkoop’s words when he wrote: “The hasty flight of the Indians … convinces me that they are influenced by fear alone, and … that no council can be held with them in the presence of a large military force.” Unfortunately, Custer’s despatch on April 17 accused the fleeing Cheyennes of committing depredations at Lookout Station—unfortunate because his report of April 19 cleared the same Cheyennes of the misdeeds but would arrive too late to save the village. As the days of waiting passed hour by agonizing hour for reports from Custer, Wynkoop waited in vain for an answer from Hancock. None was forthcoming.

Although Hancock had no intention of addressing the situation with Wynkoop, he did not burn the village the next morning. On April 17, he sent Lt. Gen. William T. Sherman, commander of the Division of the Missouri, a copy of Wynkoop’s formal protest. “I have made no written reply [to Wynkoop] as yet,” he wrote, “and probably will not make any at all—certainly not before I leave this place.” Next, he spoke of how it would be difficult to destroy one village without destroying the other. Then on April 18, Hancock, ignoring Wynkoop’s objections, made a decision—he would confiscate the property in both villages and then destroy both. True to his word, the next day the general burned both villages.

When Hancock moved on to Fort Dodge, an angry Wynkoop accompanied him. Here the Tall Chief began an assault of words on Hancock. When he learned that six Cheyennes were attacked and killed by troopers from the 7th Cavalry the same day the village was burned, he exclaimed: “This whole matter is horrible in the extreme, [the] Indians of my agency have actually been forced into war.” Next, Wynkoop lashed out at Hancock’s burning of the village: “General Hancock has declared war upon the Cheyennes, and ordered all to be shot who make their appearance north of the Arkansas or south of the Platte Rivers. The question is, what have these Indians done to cause such action?”

Wynkoop had no intention of letting up and made it known that the Cheyenne and Sioux villages were easily identified. Hancock, in turn, wrote: “I can only say that the villages stood upon the same ground, and I was unable, after an inspection which I made in person, to distinguish with any certainty the lodges of the Cheyennes from those of the Sioux.” Wynkoop found this statement incredulous. How, he wondered, could Hancock say this, when his inspector general distributed an inventory to him that listed the property in the Cheyenne village as well as that in the Sioux village. To have had made the chart, someone had to have made a decision about which village belonged to which tribe. On April 24, Wynkoop submitted his inventory for all that was destroyed in the village, listing two categories: Cheyenne and Sioux.

When Hancock reported that some eight hundred Cheyennes, Sioux and Pawnee crossed the Smoky Hill road on April 16, Wynkoop again took the general to task. “I would beg leave to draw your attention to the fact that is well known by every man who has the least knowledge of Indian affairs in this country, that the Pawnees are the hereditary enemies of the Cheyennes and Sioux, and war has always existed between them.” In fairness to Hancock, it should be noted that his report was based upon Custer’s April 19 report, which erroneously stated that the Pawnee rode with the Cheyennes.

The Dwindling Hope of Peace

As April drew to a close, Wynkoop clung to his belief that another war could be prevented—but only if the Department of the Interior moved quickly and stopped the military from forcing the issue. That May Wynkoop had his interpreters roaming the land looking for his wards. By month’s end, a good portion of the Arapaho and Southern Cheyennes camped on the Washita River in Indian Territory. They were nervous about their future. Although the Arapaho wanted nothing to do with war, the Cheyennes were a different matter—most were angry over how they had recently been treated by either Hancock or the people on the Arkansas River.

As spring began to fade the Tall Chief remained in the land of the Tsistsistas, to “exert myself to further the public interests as long as I hold the position I now occupy.” But this would not last long, and by early June he returned to Larned to secure annuities for his wards who did not go to war.

It should be mentioned that Wynkoop was no fool. He knew that he would once again be blamed for destroying a Cheyenne village. Although he would claim that military operations prevented him from directly contacting his wards, the real reason he remained close to Larned and did not try to personally contact them was that it was too dangerous to walk among the Cheyennes at this time. And he was right. As the days of summer warmed, the Cheyennes and their allies raided from the Arkansas and Smoky Hill rivers clear to the South Platte.

Although Wynkoop had not seen his wards in some time, by July 1 he remained convinced that many of them had not committed any depredations. His main concern was that the military would “strike the wrong Indians which will force these friendly Indians, who are disposed and anxious to remain at peace, to make war in self defense.” He did not want an innocent village attacked. Continuing, he wrote: “I therefore consider it of the utmost importance that these Indians should be separated, and those whom I can vouch for, as friendly[,] be brought under protection, while the campaign is being carried on against those who deserve punishment.”

Wynkoop had just predicted the future, a dark future that he evidently could not handle. Although peace would once again return to the land that autumn when a treaty was signed during the Moon of the Changing Season at a creek called Medicine Lodge, war would again return to the prairie in 1868. By then Wynkoop was aware that his every effort to prevent war had failed, and there was no denying that many Cheyennes rode the war trail. Whites cried out for extermination. Unsure of what to do, Wynkoop fled east to hide. That November he was ordered back to the frontier to gather the Cheyennes in Indian Territory. But times had changed. Unlike the previous year when he had felt that innocent people could be protected if assembled in one location, this time the Tall Chief sensed disaster. On November 29, he wrote Commissioner Taylor: “[The Cheyennes] will readily respond to my call [to congregate at Fort Cobb], but I most certainly refuse to again be the instrument of the murder of innocent women and children.” He tendered his resignation, and the Cheyennes lost perhaps one of the best white friends they ever had.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments