By Eric Niderost

Marshal Gouvion Saint-Cyr was in a tight spot, and he knew it. It was the morning of August 26, 1813, and Saint-Cyr and his French XIV Corps were defending Dresden, the capital of Saxony, from a large and menacing Allied army that outnumbered his own by at least four to one. But if Saint-Cyr had any doubts about his ability to hold the city, he kept them to himself. Nicknamed “the Owl,” Saint-Cyr was an intellectual whose cold, efficient manner commanded respect, if not love, from his soldiers. The battle had started around 5 am, with Austro-Russian attacks increasing in scale and intensity. The French had been forced to give ground, but so far their strongpoints had held against all odds.

Fortifying the “Florence on the Elbe”

As the sun rose higher, Dresden was revealed in all its glory, a baroque gem of a city known far and wide as “Florence on the Elbe.” It was like a fairy tale come to life, with jewel-like palaces rising at every turn and the city skyline crowded with splendid church domes and fanciful towers that spiked the sky. Saint-Cyr had trained as a painter in his youth and was a fine musician. He might have appreciated the splendors all around him had he not been preoccupied with more urgent military matters.

Indeed, the arts of peace took second place to the necessities of war. A few weeks earlier, Napoleon had ordered a major strengthening of Dresden’s defenses. Dresden was a city of some 30,000 souls that straddled the Elbe River. The Altstadt, or Old City, and its patchwork quilt of suburbs lay on the left bank, while the smaller Neustadt (New City) nestled on the right bank. The Old City was ringed by a partly demolished medieval wall. Major streets were barricaded, houses were fitted with gun loopholes, and artillery platforms were erected. The Gross Garten, or Great Garden, a landscaped park that lay to the southeast, surrounded by a wall, guarded Dresden’s approaches in that direction and was considered a strongpoint.

Napoleon directed that the seven gates to the suburbs be blocked and the Pirna Gate be strengthened by excavating a ditch in front of it that could be filled with water. Saint-Cyr was counting primarily on the 13 redoubts that ringed the city like a necklace. So far, they had successfully stopped all Allied attacks—but how long could they hold out?

Shortly after 9 am, Saint-Cyr heard something between the booming cannon reports. At first indistinct, it became clearer as hundreds of soldiers took up the cry: “Vive l’Empereur! Vive l’Empereur! Vive l’Empereur!” Saint-Cyr was elated. The swelling chorus of cheers meant only one thing—Napoleon had arrived in Dresden. With the emperor present, potential defeat might well be changed into victory. Napoleon’s charisma was so great that he instilled everyone, from Saint-Cyr down to the lowest private, with newfound confidence in their ultimate triumph.

Reeling From the Failed Russian Invasion

The contest for Dresden was part of Napoleon’s last-ditch effort to shore up the crumbling remains of his grand empire. In 1812 he had invaded Russia with a multinational army of 600,000 men. The Russian campaign played out like a Greek tragedy: Napoleon’s hubris led to disaster. He lost more than 500,000 men in the debacle, as well as 200,000 trained cavalry, artillery, and transport horses. Ironically, the men could be replaced, but the horses could not. Cavalry was the eyes and ears of an army, the shock troops that galloped forward to clinch a victory when the enemy retreated. Napoleon’s relative lack of cavalry was to figure heavily in the 1813 campaign.

Eager to throw off the French yoke, Prussia joined Russia in what became the nucleus of the Sixth Coalition against France. In those early months of 1813, Austria remained neutral. In spite of its dynastic ties with Napoleon—Austrian-born duchess Marie Louise was his wife and empress—Austria had little love for the man they considered a Corsican upstart. By the same token, Vienna had little affection for Russia either, and feared czarist expansion into central Europe.

For the moment Vienna thought it wise to wait, using the time to play the role of honest broker between the opposing sides. Austria’s chief diplomat, Prince Clemens von Metternich, played his cards well, arranging a personal interview with Napoleon while secretly negotiating with Russia and Prussia. By the time the German campaign opened in April 1813, Napoleon had managed to muster an army numbering nearly 200,000 men and 372 guns—a miracle of improvisation under very trying circumstances. Yet on closer inspection, the new Grand Armée bore little resemblance to the famous Grand Armée that had won the Battles of Austerlitz, Jena, and Friedland only a few years earlier.

Napoleon glumly acknowledged his lack of cavalry. He wrote that he could finish matters very quickly “if only I had 15,000 more cavalry; but I am rather weak in that arm.” The army’s troubles went deeper than that. It took time to adequately train cavalry, and time was something in very short supply. Most of the troopers were young, and 80 percent had never even ridden a horse. They were hastily trained and barely knew such basic skills as taking care of a mount. The senior officers were veterans and the ranks were stiffened by old NCOs who had been promoted to lieutenants. In some cases, even retired officers were recalled to the colors.

The infantry wasn’t much better. Most were callow youths, eager but lacking the strength and stamina needed for a grueling campaign. An inspection report ruefully admitted that “some of the men are of rather weak appearance.” Barely out of their teens—and some much younger—they scarcely knew how to load and fire their Charleville muskets.

Even after the catastrophic Russian campaign, Napoleon’s name still retained much of its magic. If the emperor was with them, these young recruits were sure that France would emerge victorious. And despite their youth and inexperience, these new soldiers fought well. French officer Jean Barres recalled: “Our young conscripts behaved very well [in battle]; not one left the ranks. Our company was disorganized: it lost half its sergeants and corporals but we were confident in the genius of the emperor.”

Austria Joins the Sixth Coalition

In May 1813 Napoleon won two hard-fought battles at Lutzen and Bautzen, but the shortage of cavalry and the sheer exhaustion of his young conscripts prevented them from becoming decisive victories. In June the emperor agreed to an armistice. He later regretted the decision, calling it one of the worst mistakes in his career.

At the time there were good reasons to seek breathing space. The French had lost 25,000 men since the beginning of the campaign. Even more significantly, another 90,000 were on the sick lists. Thousands more were stragglers, not deserters but unable to keep up with the marching and countermarching through the length and breadth of Germany. The young recruits had fought well, but if the spirit was willing, the flesh was weak.

Negotiations with Austria soon broke down. Metternich, feeling that Napoleon was vulnerable, secretly cast his lot with the Allies. Austria in effect demanded that the Napoleonic empire be dismantled east of the Rhine. Prussia would be restored to its 1805 boundaries and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Confederation of the Rhine would be abolished.

The terms were purposely outrageous, and predictably Napoleon rejected them. On August 12, Austria declared war against France and formally joined the Sixth Coalition against the emperor. Sweden also joined the Allies, led by Swedish crown prince—and former French marshal—Jean Baptiste Bernadotte. Counting reserves and second-line troops, the coalition could now field some 800,000 men.

As always, Great Britain was the coalition’s paymaster. The island nation pledged two million pounds to Russia and Prussia, and Austria would also share in the largesse. Fueled by British gold and backed by enormous reserves of manpower, the Allies felt confident they could defeat France. But they were still fearful of Napoleon, and there was much debate in Allied headquarters about how to neutralize his genius on the battlefield.

The Allies would have three main field forces: the Army of the North, the Army of Silesia, and the Army of Bohemia. The Army of the North, some 110,000 Prussians and Swedes under the command of Crown Prince Bernadotte, would be in the Berlin region. Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blucher’s Army of Silesia (95,000 men) would be massed around Breslau. The main Allied force was the Army of Bohemia, 230,000 strong, led by Field Marshal Prince Karl Philip von Schwarzenberg.

Three Bothersome Monarchs

The Allies were divided on how to open the new phase of the campaign. Plans were put forward, only to be rejected after passionate squabbling. But one thing united all parties: a healthy fear of Napoleon’s genius. They had been given a bloody nose at Lutzen and Bautzen and were not anxious to repeat the experience. Eventually, a plan was adopted that grudgingly acknowledged the emperor’s gifts. The Allied armies would assiduously avoid battle if Napoleon was present, and if he was advancing in person with his main army they would retire as quickly as possible. Allied forces would threaten his line of communications and, if possible, defeat Napoleon’s subordinates whenever an opportunity to do so presented itself.

The basics of the plan came from Schwarzenberg’s chief of staff, General Count Johann Josef Radetzky von Raditz. Radetzky was essentially proposing a war of attrition, wherein Napoleon would be worn down by a series of fruitless marches and countermarches. Radetzky was unknown at the time but was destined to find a sort of immortality many years later when composer Johann Strauss composed “Radetsky’s March.”

Schwarzenberg was a competent soldier who was prone to moments of hesitation and tended to be overcautious. Archduke Charles of Hapsburg, the Austrian emperor’s brother, might have made a better choice as commander in chief. While it was true that Napoleon had defeated Charles at Wagram in 1809, the archduke had a record of notable victories during the course of his 20-year career. Charles had actually defeated Napoleon at Aspern-Essling, a rare accomplishment. Some have said that sibling rivalry might have played a part in the archduke being passed over. In any event, Emperor Francis I decided to give Schwarzenberg the coveted position.

Czar Alexander I of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and King Frederick William III of Prussia accompanied the Army of Bohemia and were present at Schwarzenberg’s headquarters. The harried prince found them three albatrosses around his neck, often intervening at inappropriate times and adding to the confusion when crucial decisions had to be made. The presence of the three monarchs also brought in a host of court flunkies, hangers-on and political parasites. “It is really inhuman,” Schwarzenberg complained, “what I must tolerate and bear, surrounded as I am by fools, eccentrics, projectors, intriguers, asses, babblers, and niggling critics.”

Marching on Dresden

At first, Schwarzenberg’s goal was Leipzig, but eventually Dresden became the target. By August 25, the Army of Bohemia’s advance guard under General Peter Wittgenstein was approaching the city’s southern fringes. Saint-Cyr launched a desperate attack on Wittgenstein that drove back the Russo-Prussian force and threw Allied plans into confusion. The French marshal had bought some time.

Napoleon had originally been trying to catch Blucher’s Army of Silesia, which was moving over the Bobr River to the east. Blucher was rapidly retiring, conforming to a will-o’- the-wisp strategy of avoiding a pitched battle when Napoleon was present. But when he heard of Saint-Cyr’s plight, the emperor eventually decided to bring the bulk of the Grand Armée to Dresden. Not only was Dresden the capital city of his ally, King Frederick Augustus of Saxony, but it was also Napoleon’s hub for the entire campaign. Artillery parks and supplies were stockpiled there. If the Allies could be caught napping, Napoleon hoped to make Dresden a second Austerlitz.

Once again, too much discussion and internal wrangling almost wrecked the Allied war effort. After much debate, Schwarzenberg decided that the Army of Bohemia would launch a demonstration or reconnaissance in force against Dresden. A full-scale assault might come later.

Five columns would participate in the effort, but there would be little or no coordination between each column. Worse still, attacking troops had no equipment to help them bridge ditches and no scaling ladders to help them climb the French redoubts. The whole plan was a slapdash affair, typical of the half-baked compromises that all too often came out of Allied councils of war.

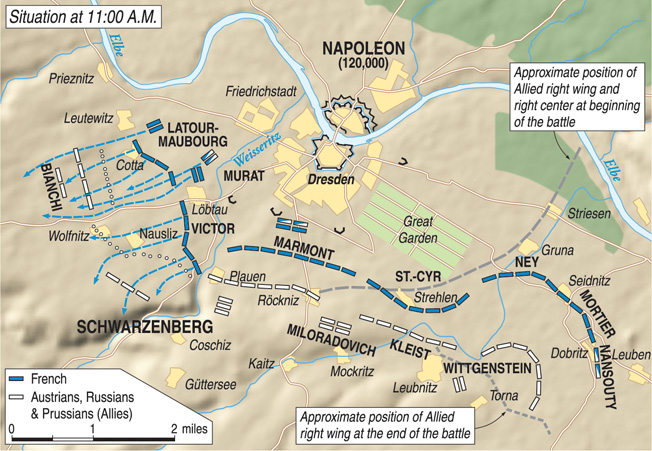

The command structure of the demonstration would be simple, as befitted an operation with limited objectives. The Army of Bohemia would be divided into two distinct wings. The left wing, led by Schwarzenberg himself, would consist of the Austrian III Corps, Austrian IV Corps, Austrian Reserve Corps, and Reserve Artillery. Wittgenstein would command the right wing, a multinational force that included the Russian Advance Guard Division, Russian I Corps, Prussian II Corps, and reserve artillery.

“The Victory is Ours”

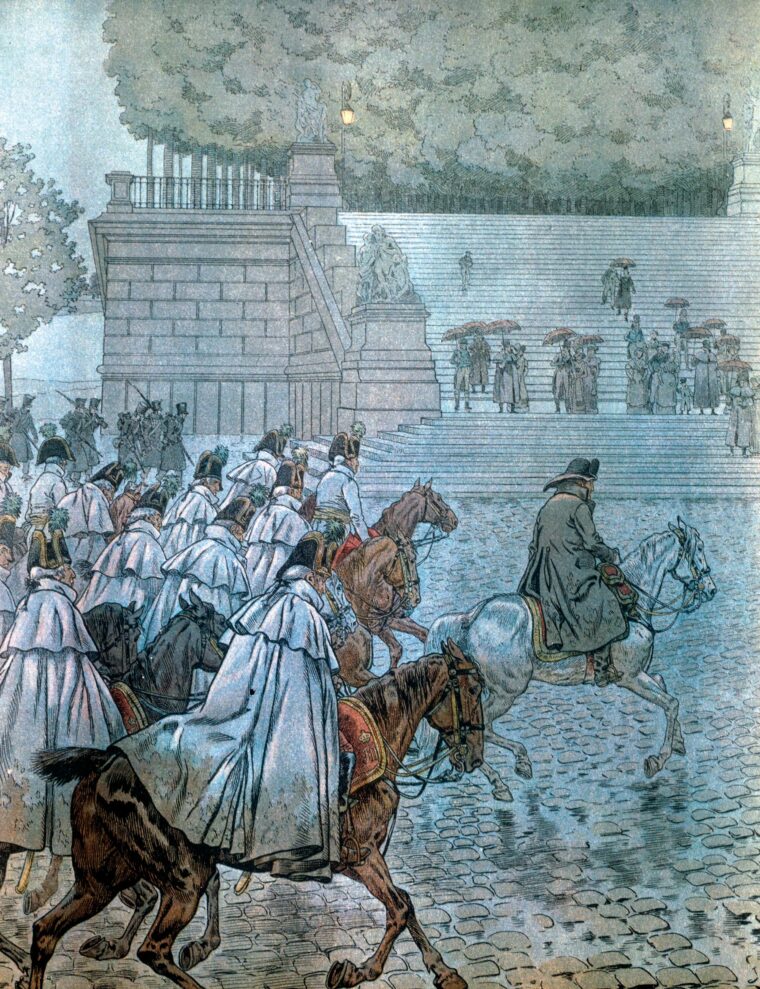

When Napoleon arrived in Dresden his mere presence galvanized the city. Crowds gathered and soldiers tried to press near to get a better glimpse of him as he rode by. There he was—the man of destiny in his gray overcoat and legendary black cocked hat, surrounded by a small staff. He had arrived first; the rest of the army was on its way.

The Imperial Guard—both Young and Old—arrived in the city an hour after Napoleon. The roads were choked with dust and the heat was stifling, but the Guard was in good spirits, because here was a chance for action. Although their mouths were dry and parched with thirst, they entered Dresden singing, “The victory is ours!”

At about the same time, Emperor Francis was engaged in a debate that involved Czar Alexander, King Frederick William of Prussia, and senior Allied officers. When the Allied command realized that Napoleon was in Dresden, the fear and consternation were palpable. Most of the planners favored immediate withdrawal. Only Frederick William insisted that they launch the planned major offensive, an advance that was supposed to involve some 150,000 men. The Prussian king was overruled, but it took time for withdrawal orders to travel down the chain of command. Before that could happen a signal cannon boomed, announcing the start of the general assault. For better or worse, the Allies were now going to take on Napoleon himself.

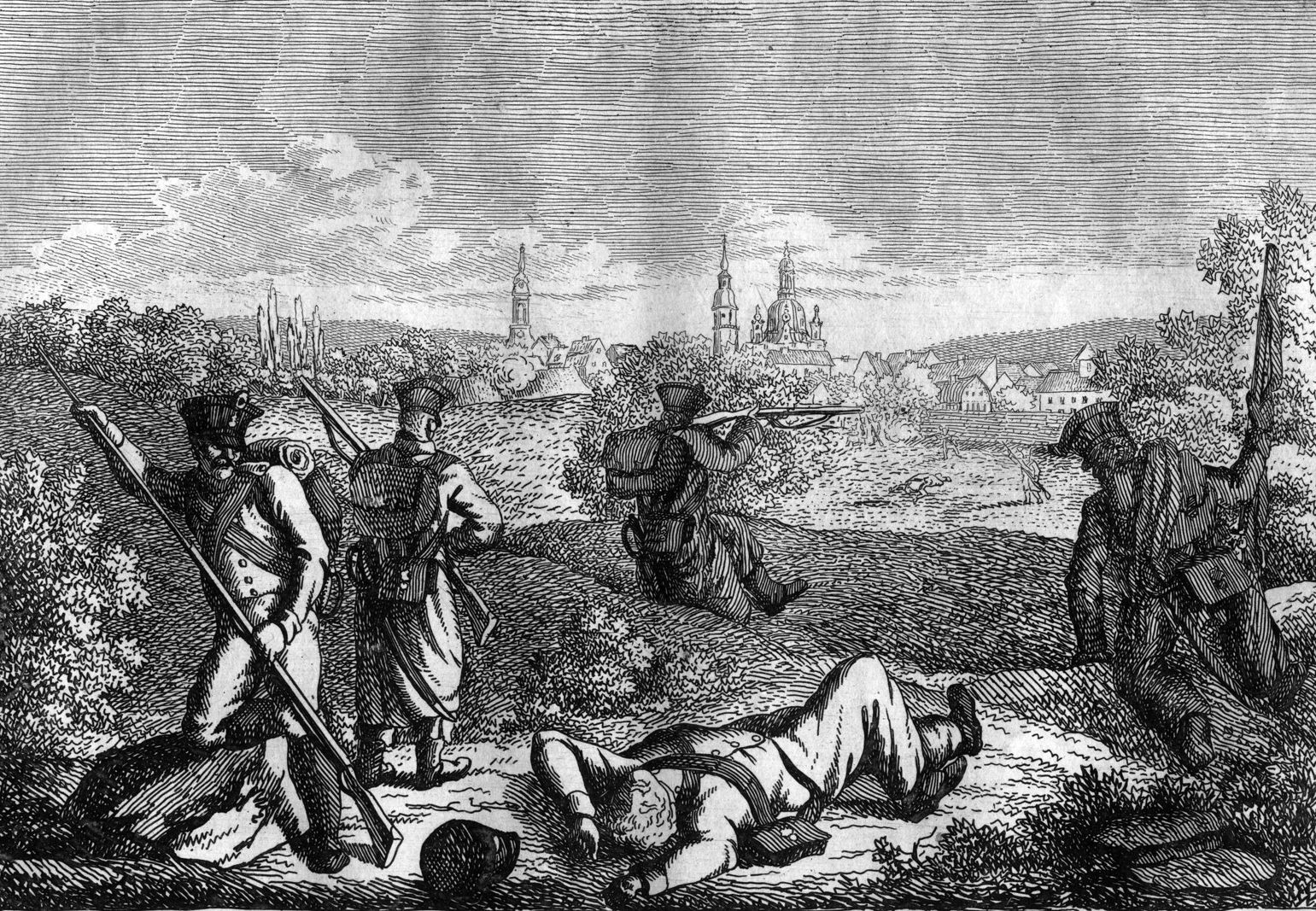

When Napoleon entered Dresden, he made his way to the front lines to inspect French positions and consult with a relieved Saint-Cyr. The emperor swept the horizon with his telescope, taking note of enemy positions and the progress the Allies had made thus far. He wanted to know what had happened before he arrived on the scene. The fighting, he was told, had been uncoordinated but intense. The Prussians had managed to break into the Grand Garden, but their progress was impeded by stubborn French resistance. The attack was seconded by Russians, who came into the garden via its northeastern corner. After two or three hours of see-saw fighting, the Prussians and Russians had managed to secure about half the garden, including a small baroque palace in its landscaped center.

Around 7:30 am the Russians attacked the ground between the Grand Garden and the Elbe, but their advance was stalled by heavy French artillery fire from the river’s right bank. French shells tore through green-coated ranks, forcing the survivors to fall back in disorder. Although Napoleon’s infantry and cavalry had declined in quality, his artillery was still as formidable as ever. Around 11 am there was a pause in the fighting that lasted several hours. It gave Napoleon time to finish his inspections and devise his own offensive plans. The emperor generally approved of how Saint-Cyr had conducted the battle thus far, but noted that there had been flaws in the French defenses even before the first shot had been fired. Some of the redoubts were relatively weak, with only one cannon each on their ramparts.

Napoleon was also unhappy that French engineers had failed to demolish a large building that stood in front of Redoubt 4. The Allies had taken advantage of the glaring omission and now occupied the building. Some of the French redoubts had been placed in such a way that they did not have mutually supporting fields of fire. Napoleon saw to it that these strongpoints were made stronger—one redoubt got a battery of 12-pounder cannons.

The French Imperial Guard paused at Neustadt Bridge, one of the spans that crossed the Elbe and linked the New City with the Old City. The guardsmen sank to the ground, weary after the long forced march, and used their knapsacks as pillows. Others gratefully accepted drinks of brandy the locals offered, downing the fiery liquid in one or two gulps.

The French Reserve Cavalry arrived at 2 pm, led by the flamboyant Joachim Murat, former marshal of France and current king of Naples. A legend in his own time, Murat was the finest cavalry commander of the Napoleonic Wars. His cavalry included both heavy and light cavalry, armored cuirassiers, lancers and chasseurs ever ready to engage enemy horsemen and exploit any breakthrough that should occur.

Fighting at the Grand Garden

The battle began again at 3 pm. Once again, the battered Grand Garden was the focus of heavy fighting. The Russians surged forward, men of the 20th, 21st, 24th, 25th, and 26th Jagers and the Selenguinsk Infantry Regiment. They moved forward through the garden, then assaulted French Redoubt 2, a tide of green uniforms lapping at the base of its walls.

To counter the Russian move, Marshal Adolphe Edouard Mortier led Napoleon’s Young Guard into action. The guardsmen lived up to their reputations, driving the czarist troops back with heavy loss and recapturing half the garden. In the center, in the area between Redoubt 3 and Redoubt 4, the Allies initially had better luck. Austrians advanced on Redoubt 3 through a hurricane of French artillery fire and musket volleys. The French 27th Light Infantry was particularly steady, firing and loading with clockwork regularity.

The Austrian advance stalled, but then something like a miracle occurred. French fire from Redoubt 3 weakened, then stopped altogether. The redoubt’s garrison had run out of ammunition. Heartened by this unexpected turn of events, the white-coated Austrians renewed the attack, crossing Redoubt 3’s protective ditch and scrambling up its walls. The French were waiting with fixed bayonets.

After a furious and bloody bayonet fight—rare in the Napoleonic Wars—the French gave way, with survivors retreating into the Maszcynski Garden immediately behind the redoubt. The Austrians followed, but soon the tables were turned. French reserves came to the rescue of their beleaguered comrades, pouring out of the garden like a swarm of angry bees. The Austrians were forced to relinquish their hard-earned prize, and several hundred white coats, trapped by Redoubt 3’s surrounding walls, were compelled to surrender. After the battle, some 180 French and 344 Austrians were found dead in Redoubt 3.

The Allies had little luck on the far left, either. Beyond the Weisseritz River, the Austrians under General Friedrich von Bianchi suffered rough handling by French artillery batteries in front of Friedrichstadt and flanking fire from French Redoubt 5. Some Austrian units managed to reach the Elbe River, but were forced to retire to avoid being cut off by Murat’s French, Polish, and Italian cavalry.

By nightfall most of the Allies’ initial gains had been wiped out by successful French counterattacks. Lost redoubts were back in French hands, and even the Great Garden was a French possession. There was a growing sense of jubilation in the Grande Armée, a euphoria enhanced by the arrival of two additional corps—Marshals Auguste Marmont’s VI Corps and Claude Victor’s II Corps—which arrived that night, footsore but in good spirits.

With the fighting temporarily at an end, Napoleon went back to the king of Saxony’s palace to plan for the next day. The addition of Marmont and Victor brought the French army up to about 120,000 effectives. The Allies still outnumbered them at 180,000, but Allied morale was low. The day had started out promising, but they had lost almost all their hard-fought gains. A sense of futility pervaded the Allied camp. The French had lost 2,000 killed and wounded, but Allied losses were much greater—4,000 dead and wounded and another 2,000 taken prisoner. Despondency spread through Allied ranks, and many feared worse was to come

That night torrential rain soaked the battlefield, causing the Weisseritz River to rise and creating a large watery obstacle. With the river in flood, it formed a barrier between the Allied left and center, save for a single bridge at Plauen. If the bridge fell into French hands, communications—indeed, all contact—would be severed between the two Allied groups.

Pushing the Sixth Coalition Back

Early the next morning, Napoleon ascended a church tower to analyze Allied positions with his telescope. At dawn the rains had ceased, replaced by a clammy fog that hovered in some areas and covered at least some of the previous day’s carnage. The rain would soon return, and would play its part in the events of the day. The emperor was planning a double envelopment with two powerful attacks on the Allied flanks—Marshals Michel Ney and Mortier from the left, Victor and Murat’s cavalry from the right. The center would be held by Saint-Cyr and Marmont, the Imperial Guard being held in reserve.

The Allied plan of battle was straightforward, even unimaginative. About two-thirds of their army would attack Napoleon’s center. That left Generals Bianchi (left wing) and Wittgenstein (right wing) with 25,000 men each to hold the flanks. But in leaving their flanks relatively weak, the Allies played right into Napoleon’s hands. The second day of battle opened at 6 am with Mortier and Ney pushing Wittgenstein’s soldiers out of Blasewitz Woods. TheYoung Guard tried to take Leubnitz but was repulsed three times by a courageous garrison of Prussians and Russians. The Allied-held village of Seidnitz also successfully resisted Napoleon’s onslaught, at least for a time.

In general, however, Napoleon’s plans were succeeding, and it looked like a major victory was in the cards. The Allies were being forced back, in some cases a mile or more. French artillery proved itself superior again to Allied guns, pounding Allied strongpoints and smashing enemy cavalry and infantry formations.

Murat’s Last Hurrah

On the French right the stage was set for one of the greatest cavalry actions of the Napoleonic Wars. It was led by Joachim Murat, dressed in a Polish-style tunic, violet breeches, and canary-yellow boots. The theatrical costume was typical of the man, conveying his devil-may-care, swashbuckling image.

Dresden was going to be Murat’s last hurrah. Within a few months he was going to switch sides, abandoning Napoleon’s cause to save his own throne. The emperor considered Murat an “imbecile” and “without judgment” off the battlefield, assessments that were harsh but had the ring of truth. But for now, dripping with gold braid and a feathered hat, he was in his element. Murat marshaled his horsemen into two lines. The first line had two sections. The section near the Elbe River consisted of General Louis Pierre Chastel’s 3rd Light Cavalry Division, mostly chasseurs. The section near Cotta was made up of cuirassiers and dragoons of General Jean-Pierre Dourmerc’s 3rd Heavy Cavalry Division. The second line was just as powerful, namely General Etienne de Bordesoulle’s 1st Heavy Cavalry Division, made up of both French and Saxon cuirassiers.

It was an impressive spectacle—rank after rank of superb horsemen moving with precision and dispatch. Thick, viscous mud from the rains slowed the advance to a fast walk. Five squadrons of Saxon cuirassiers smashed into some Austrian hussars, driving them back in disorder. General Baron Joseph von Mesko’s Austrian 3rd Light Infantry Division was the next target of Murat’s rampaging horsemen. Mesko stood his ground at first, forming his division into anticavalry squares. A volley or two sent the first French troopers packing, but they soon returned with a horse battery, which unlimbered at close range and fired round after round of canister into the packed squares.

It was more than flesh and blood could stand, and the shattered remnants surrendered. Some of Mesko’s other squares still held out, white-coated islands in a sea of French and Saxon cuirassiers. The armored warriors slashed and stabbed at will with their long swords. In normal situations, cavalry would be powerless to break an infantry square. But the rains had come again, and many of Mesko’s men found their muskets were useless because their powder was wet.

Demoralized, hungry, and exhausted, the bedraggled troops on the Allied left also discovered they were trapped. The French had taken Plauen, together with its vital bridge. Regiment after regiment laid down their arms. Two companies of Austrian infantry, their backs against the Weisseritz River, tried to maneuver, but the marching was in vain and only delayed the inevitable. French dragoons followed them, loading their carbines under their cloaks to shield the weapons from the rain. Their ploy was successful, and the horsemen managed to shoot a devastating volley into the white-coated ranks. The two companies surrendered, accepting their fate. The Austrian 3rd Light Division had ceased to exist. Mesko himself was captured by a trooper from the French 23rd Dragoons. The Allied left wing was destroyed, with 13,000 prisoners and 150 standards taken.

One of Napoleon’s Last Triumphs

In the center, Saint-Cyr and Marmont were hard pressed, and when the fighting died down in the late afternoon, Napoleon fully expected a third day’s fighting. But the Allies had had enough. There was some talk of an attack to separate the French left from the center, but the proposed ground was a morass. The Allied command knew full well that their entire left wing had been wiped out—hardly an encouraging state of affairs. Czar Alexander narrowly escaped death when a cannonball flew near him. The projectile hit General Jean Moreau, one of Napoleon’s enemies who had been exiled from France. The stricken Frenchman had both legs amputated, but the surgery failed to save his life.

Schwarzenberg ordered a night retreat. By any standard Dresden was a great French victory, one of the emperor’s last unalloyed triumphs. The Allies had lost 38,000 men, the French barely 10,000. For a brief moment it seemed as though Napoleon’s star was once again in the ascendant. Early on May 28, the French realized the Allies were gone. Napoleon ordered a pursuit, but he was less attentive to the details because he became gravely ill. Soaked to the skin by the driving rain, he was seized with violent stomach pains. Distracted by illness, he did not supervise the pursuit as closely as he would normally have done. News that his subordinates had been defeated in his absence at Katzbach and Kulm all but canceled out Napoleon’s great triumph at Dresden. It would prove to be his last significant victory.

was there ever talk of gold hoop earrings given to the men by a French Commanding officer. I have inherited the set given to my Great Great Great Grandfather who was in the war of Dresden. The rings were the heavy clouds of suffering and death which encircle and engulf every battlefield.