By Blaine Taylor

At 10:30 on the night of May 9, 1936, as 400,000 people stood crowded together on Rome’s Palazzo Venezia underneath the most famous balcony in the world, Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, 52, the leader of the country’s ruling Fascist Party, strode forward and began to speak to the silent masses below him.

“The destiny of Abyssinia has been sealed today!” he intoned in the deep, powerful voice that enthralled millions via radio down the length of the Italian “boot,” and millions more around the globe.

“Italy has her empire!” he roared, thus having avenged the defeat in 1896 at the Battle of Adowa in far-off East Africa of the Royal Italian Army in what had been the most humiliating massacre of any white colonial force in history, all the more galling at the hands of a black host.

At one stroke, Mussolini made Italian King Victor Emmanuel III of the reigning House of Savoy an emperor too.

Bathed in the light of flood lamps, the king’s appointed head of government since 1922 stood immobile, his hands gripping the stone balustrade of the balcony, gazing immobile as his worshippers below chanted over and over, “Duce, Duce, Duce!”

Drunk with the hyped euphoria of the moment, one of Mussolini’s top Fascist satraps blurted out of their chief, “He’s like a god!” but another corrected him thus, “No, not like a god—he is a god!”

But both they and the object of their overripe veneration had forgotten the dictate of an earlier Italian premier, Count Camilo Cavour, who asserted, more correctly, “The roar of the crowd in the piazza is not the voice of the people.”

By Mussolini’s last appearance on May 5, 1943, which happened on that same balcony, his world had fallen apart on many levels in an almost unprecedented historical reversal of fortune.

The British Eighth Army in Egypt had not only routed a much larger Italian force driving on Cairo, but had also taken hundreds of thousands of prisoners, thus imperiling Italy’s Libyan colony in North Africa, taken from the Turks in 1911.

Il Duce’s invasion of Greece in October 1940 was not only repulsed by the hardy Greeks, but yet another Italian invading force had been driven off, with the Greek Army invading Mussolini’s neighbor Albania, occupied in 1939.

In 1941, the former captive Italian colony of Ethiopia had been returned to its rightful ruler, Emperor Haile Selassie, after a British army badly defeated the Fascist occupiers who had conquered it in 1936.

In the cases of both the Western Desert and the rugged mountain terrain of ancient Greece, the crestfallen Duce had suffered double embarrassments from which his stronger German allies had to bail him out with their own troops, winning victories that his armies had failed miserably to achieve.

The expeditionary corps that he had sent to help Hitler conquer the Soviet Union had been blamed for a major part of the German debacle at Stalingrad in November 1942, with its veterans returning home hating their contemptuous German “allies.” Many even joined the anti-Axis Communist partisans in protest, fighting the Nazis instead.

His much vaunted fleet had been badly mauled at the Italian naval base at Taranto, and the famed Italian Folgore parachute troops had failed in their attempt to seize Malta. Thus, the Mediterranean was still a British lake rather than what Il Duce most desired, “our sea,” while the Royal Navy remained steadfastly at anchor at Gibraltar, the rock that remained a British bastion at the gates of the Mediterranean.

In the “conquered” Balkans, the Italian armed forces were waging a no-win, antiguerrilla war against both former Yugoslav royalist troops and a newly risen force, Communist partisans under Tito.

After the surrender of all Axis forces in Tunisia in May 1943 came the stunning Allied invasion of Italian territory itself, starting with the island of Pantelleria, followed by Sicily, the latter being defended far more by the Germans again than by the resident Fascist forces.

Everyone, especially Mussolini himself, could predict the Allies next move, the invasion, conquest, and occupation of Italy.

Only one man could prevent that dire outcome and thus save Il Duce his premiership, the Fascist Party its rule, and his majesty’s throne: German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, but the Führer would not do what Mussolini urged to reverse the dire situation in the Mediterranean.

In a blunt appeal at Salzburg, Austria, in April 1943, Il Duce urged Hitler to radically reverse his own major war aim since June 1941, admitting that he had lost the war against Soviet Russia and had to make peace with Josef Stalin, thereby abandoning the East for the southern theater of war instead, and transferring all German forces from Russia to the Mediterranean.

This and this alone, Mussolini argued, would save his regime and Italy from complete defeat. Hitler rejected it completely, and as their next summit scheduled for that summer in Italy approached, Il Duce faced a plethora of plots against him and his all-too-personal regime that had ruled Italy since 1922.

These included a major triad of opponents: his own Fascist Party ruling class, the Italian Royal Army and its top leader, and King Victor Emmanuel, who alone had the legal, constitutional power to fire the man he had named premier two decades earlier.

First, there were the various disparate leading elements of Mussolini’s Fascist bosses. Among these were two bitter rivals, Dino Grandi and Roberto Farinacci. The former wanted to retire Mussolini and also be named by the king to succeed him, while the latter wanted Italian leadership of the fighting in the Mediterranean to cease altogether and taken over by the far more ruthless Germanic hordes, already in force in much of Italy proper anyway.

A third would-be administrative usurper was Il Duce’s own son-in-law, former Italian Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, husband of Mussolini’s oldest daughter, Edda. An additional potential conspirator or enemy of Il Duce was the man who succeeded Ciano as foreign minister in February 1943, the former ambassador to Poland and current undersecretary Giuseppe Bastianini. The new foreign minister urged his boss to leave the lost war behind by declaring a replay of the Italian neutrality of 1914-1915, a tack that Mussolini thought Hitler would never allow.

Giuseppe Bottai, Fascist National Minister of Education during 1936-1943, was still another potential rival. Bottai had been one of many officials ruthlessly purged from office that February when the alarmed Duce thought he had squelched all intraparty resistance to his continued mishandling of the lost war with an across-the-board shakeup of his cabinet.

He was wrong. All it really accomplished was to both solidify and expand the growing anti-Mussolini feeling among his oldest followers.

The officers of the Italian Army presented a threat of their own to Mussolini’s grip on power, chief of which was the reigning Italian Army Chief of Staff, General Vittorio Ambrosio, and his largely royalist officer corps. Ambrosio loathed Il Duce for both losing the war and constantly kowtowing to Hitler. Witnessing yet another Hitlerian browbeating of his nominal master during their meeting at the Italian town of Feltre, Ambrosio made his own, inner, final decision. Mussolini would have to go.

Then came King Victor Emmanuel III, who had already reigned in Savoyard Italy for 22 years by the day that Mussolini, then aged 39, had first taken office in 1922. He had his own secret candidate in mind to succeed the discredited Duce if it came to that, Marshal of Italy Pietro Badoglio, conqueror of Ethiopia in 1936, whom Mussolini had forcibly retired after he lost in Greece four years later. Directing the palace revolt was his majesty’s most constant in-house adviser, the Duke of Acquarone.

Despising the peasant Mussolini, the elder Marshal Badoglio simply bided his time, awaiting the expected summons from his majesty when Fascism’s fall would seem imminent. He had wanted to shoot down Mussolini and his street thug Black Shirts in 1922 with Army weaponry, but the king had balked at the prospect of civil war. Badoglio let it be known privately that he was going to overthrow the failed dictator this time, with or without his majesty’s assent.

By mid-1943, however, Victor Emmanuel worried even more about not only losing his throne, but also the overthrow of the entire ruling Savoyard dynasty if his son, Crown Prince Umberto, was forced to abdicate with him, as had happened with the German Hohenzollerns in 1918.

The king had privately decided to use the Army to remove Il Duce from office only as a last resort, knowing as he had all along that the professional military would stand with him under the leadership of Badoglio and Ambrosio, and not with Mussolini if push came to shove.

In 1943, as it turned out, only one officer of the Italian Army marshalate remained loyal to the fallen Duce to the bitter end in April 1945, even after Mussolini’s first of two falls from office.

Both the king and his premier shared a fear of the Germans more than an Allied occupation. Each man realized full well that Hitler would exact a fearsome revenge if Italy left the Axis pact, much less joined the Allies in the middle of a world war. A ruthless Nazi occupation of Italy would follow, with both Rome and Vatican City garrisoned, the pope imprisoned, maybe the royal family murdered, and the possible eruption of civil war to boot.

With the exceptions of the predicted papal takeover and the flight of the royal family, all the other feared outcomes would take place.

Thus, the stage was set when Mussolini went to meet Hitler again at the Feltre Conference in northern Italy on July 19, 1943, in the middle of which an Italian aide burst in with stunning news. Rome was being bombed for the first time in history, and the king himself was watching American bombers from the lawn of his home.

This incident persuaded Victor Emmanuel to act at last, but he first wanted a legal means to do so, via the ruling Fascist Party, and surprisingly this actually happened, as few (including Mussolini) foresaw.

On the favorable balance sheet of his political ledger, the besieged Duce could count on his innermost circle of advisers, men like Carlo Scorza, as well as on his immediate family members. Chief among the latter was his long-suffering wife, Rachele, who had already personally confronted many of the men she rightly believed were conspiring against her philandering husband, urging him to arrest them all.

The most prominent of his many mistresses, Claretta Petacci, went a giant step farther than Mussolini’s wife, however. “Execute them all!” she advised. Instead, he told Rachele, “I’m more worried about American tanks than conspiracies!” He placated Claretta with assurances that his earlier purge had made them all fear him even more.

They were right, and he was wrong.

Here is how it all transpired in the actual event. The first meeting of the Fascist Grand Council since 1939 occurred over many long hours during the night of July 24-25, 1943. For the very first time, however, members of Mussolini’s elite personal guard, the Musketeers, were not present at Palazzo Venezia, although numerous other security men were on duty.

The plotters nonetheless internally overdramatized the alleged possible, personal threat to themselves. However, two of them foolishly brought into the meeting hall concealed hand grenades to prevent their either being arrested or even murdered on the spot. Combat veterans both, they either should have known or ignored the fact that their detonation on-site in an enclosed room most likely would have killed everyone present.

In his own 1944 memoirs of the events, Mussolini asserted that no such Latin theatrics of any kind occurred. What did happen was that all present got to air their grievances to Il Duce twice in speeches that droned on for far too long, with Grandi’s alone lasting 90 minutes.

Grandi made a motion that the king retrieve all the martial command powers that he had been forced to hand over to Mussolini on June 10, 1940, when Il Duce declared war on Britain and France. In a countermotion, Farinacci demanded that the Germans be allowed to run the war completely. All of the senior Fascists believed that with Mussolini retired the king would retain every one of them in their current offices, in a sort of Fascism without Il Duce.

Mussolini alone predicted that his firing would result in the simultaneous overthrow of the entire Fascist regime, meaning that all of them would go—starting with would-be Mussolini successors Grandi and Ciano. He turned out to be right.

Nevertheless, Mussolini was voted out 19 to eight, prominent among those against him was his own relation, the traitorous Ciano, who was shot by a Fascist firing squad six months later. As Mussolini was driven home, Grandi carried the news of the event to his majesty, setting the scene for the next afternoon meeting at the king’s Villa Savoia residence in Rome.

Given back his military powers of command, Victor Emmanuel now also had the legal pretext he had counted on, since Mussolini’s own party had voted “no confidence” in Il Duce’s leadership.

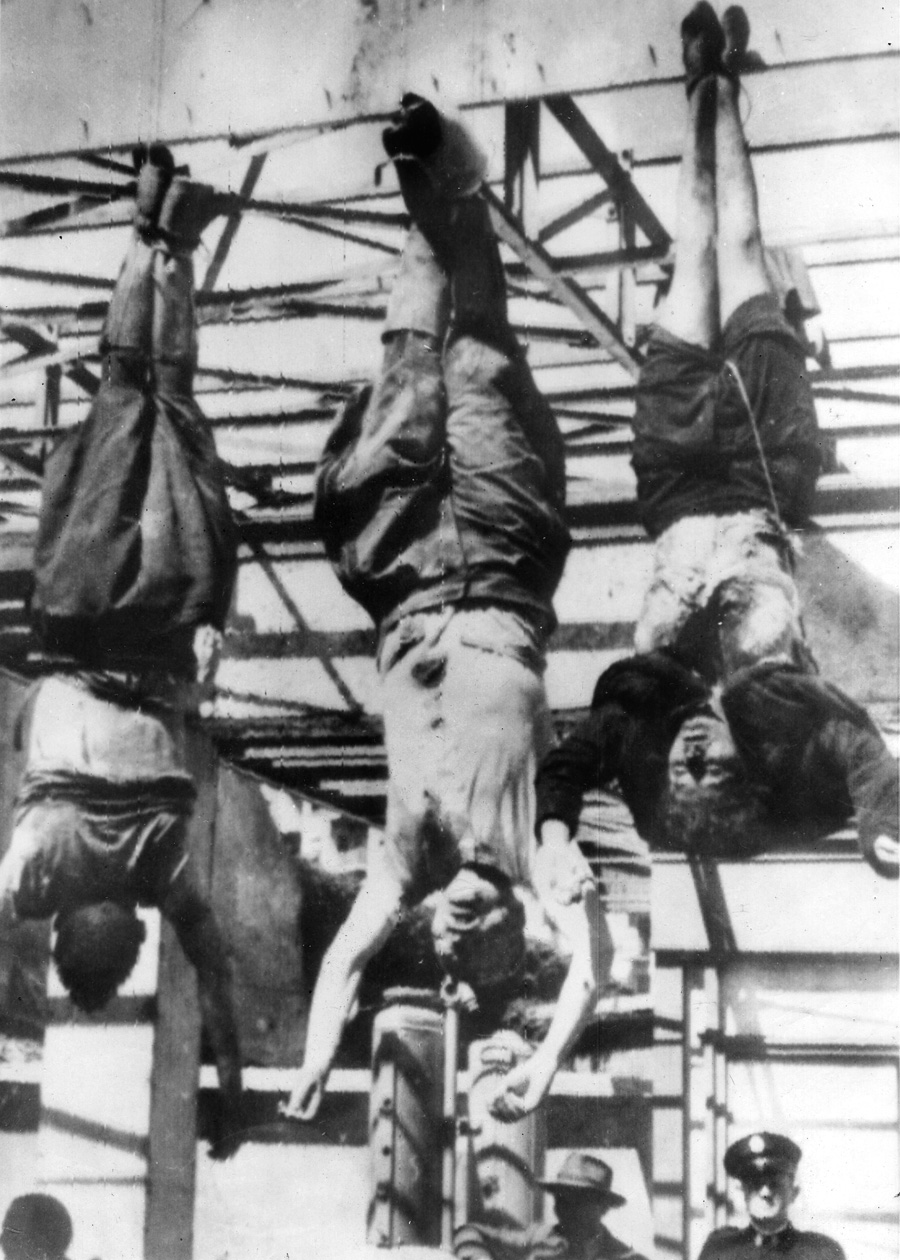

mistress Claretta Petacci are strung up along with those of other Fascists after their execution.

As Grandi, his longest serving premier in office, began giving his own account of the session to the king, the latter cut him off abruptly, saying that his time in power had ended, and in effect that his resignation was accepted, all within but a few minutes of the civilian-clad Mussolini’s last arrival there.

Promised a retirement in safety at a place of his choosing, instead the ousted Fascist leader found an ambulance awaiting him outside, his own car and chauffeur out of sight. An Italian military police officer and enlisted men with pistols and submachine guns hustled him into the ambulance. Mussolini was told that the arrangement was “for your safety.” Off the ambulance raced at high speed to a local police barracks.

It was only there that the dismissed Mussolini realized that he had, in fact, been arrested and was under armed guard. That night, an unannounced public radio bulletin simply blared out the news to a shocked Roman and Italian public that Il Duce had been replaced by the new premier, Marshal Badoglio.

The latter moved swiftly to stifle any loyalist countermeasures by firing the head of the Fascist Militia, disbanding it entirely en masse, and then merging all its members into the Royal Army, both its headquarters and barracks occupied by soldiers loyal to the king rather than the disgraced man who had lost the bungled war. In the event, none of the Duce’s much ballyhooed “nine million bayonets,” and especially no Fascist daggers, were raised in any way in his defense.

Rome erupted in an orgy of anti-Fascist celebrations that Marshal Badoglio allowed for but a single night and day, with all pictures of the former ruler destroyed, symbols torn down, and party emblems literally ripped from uniforms. Stunned, the crestfallen Count Ciano hid in his Roman residence for five weeks. Grandi fled to South America until the late 1980s, and Bottai joined the French Foreign Legion, later taking part in the Allied invasion of Nazi Germany. Farinacci was shot by the Communists in April 1945.

As their former ruler had correctly forecast, none of them retained their posts or received new ones under the marshal, who announced instead that the war would continue at the side of their Axis Pact partners.

Hitler knew better, however, and ordered the immediate German military occupation of Rome, with the Americans backing off from a parachute drop to forestall it because the Royal Italian Army could not be counted upon to fight with the paratroopers against the Germans.

The king, the entire royal house, and all of Badoglio’s government fled from the Eternal City southward to eventual safety behind Allied lines. Over the course of the infamous “46 Days,” Italy was basically without a functioning government. Then came the expected announcement of September 8, 1943, that the country had changed sides in the middle of the war, now against the Third Reich and fighting alongside its former enemies, the Western Allies.

Now the Italian boot found itself engaged simultaneously in a pair of brutal wars, as the Allies invaded from the south and took Rome on June 6, 1944, with the Nazis holding northern Italy until war’s end in May 1945.

The secondary struggle was the internal civil war between the new Nazi-backed Fascist state of the Salo Republic in the German-held north versus the Communist Red and Socialist Partisans, with the Prince of Piedmont, Crown Prince Umberto, serving as his father’s stand-in field commander of the regular army with the title of Lieutenant General of the Realm from June 1944 to April 1945.

Mussolini, after enduring several stations of imprisonment on land and sea, finally found himself at a ski resort in the Italian Alps, where he was rescued by German airborne troops on September 12, 1943, the day before Badoglio was planning to hand him over to the Allies as part of the secretly negotiated armistice terms.

Until 2018, this feat of derring-do had been credited to SS commando Otto Skorzeny, but a new book just published restores it to its rightful place, the German Luftwaffe commanded by General Kurt Student and the on-site officer, Major Harald Mors.

On April 23, 1945, Mussolini and Claretta were murdered by their Communist captors. Rachele and Edda were both allowed to live out their remaining lives peacefully in their native land, while King Victor Emmanuel died in exile in Egypt in 1947. His son, King Umberto II, was voted out of office in 1946 after only 34 days on the throne in favor of the present Italian Republic. Umberto died at age 78 in Geneva in 1983.

An incredulous Hitler had once asked the just freed Mussolini, “What is this Fascism that melts like snowflakes in the sun?”

Amen!

Blaine Taylor is the author of the 1996 illustrated work Fascist Eagle: Italy’s Air Marshal Italo Balbo. He resides in Towson, Maryland.