By Blaine Taylor

One of the major aims of the great Allied invasion of German-Occupied France on D-Day, June 6, 1944, was the securing of the port of Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy.

To that end, Allied supreme commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower committed three airborne divisions—the British 6th and the U.S. 82nd and 101st—to drop over Normandy in the predawn hours of June 6.

Cherbourg finally fell to the Allies on D+20, on June 27, but it had been severely demolished by the Germans before its surrender, thus rendering it useless to the invaders as a point of resupply for many weeks. Ike had foreseen this possibility, however, as he pointed out in his superior postwar memoir Crusade in Europe.

One of the most difficult problems that invariably accompanied planning for a tactical offensive involved measures for maintenance, supply, evacuation, and replacement. Before World War II, it had always been assumed that any major amphibious attack must gain permanent port facilities within a matter of days, or otherwise be abandoned. But the development of both practical and effective landing craft by the Allies, including LSTs, LCTs, DUKWs, and other waterborne craft, did much to lessen immediate dependence upon already established port facilities.

Indeed, the Allied development of many revolutionary types of equipment was one of the greatest factors in defeating the plans of the German General Staff, Eisenhower’s major opponent throughout the war.

Still, the possession of equipment and gear that allowed for the landing of material on open beaches did not automatically eliminate the need for real ports, and this was especially true with Operation Overlord, the greatest amphibious invasion in military history.

These components were towed at speeds of just three or four knots.

The treacherous English Channel was subject to destructive storms at all times of year, with winter being by far the worst period. It had been that very body of water, indeed, that had stopped would-be invaders of England through the ages, including Napoleon, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and even Hitler himself.

Ike realized that the only certain method to assure supply and maintenance was with the capture of large port facilities. Since the nature of the Nazi coastal defenses ruled out the possibility of gaining adequate ports promptly, it was necessary to provide a means of sheltering beach supply from the effects of volatile storms such as those that had wrecked the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Eisenhower well knew that even after the expected Allied capture of Cherbourg, its port capacity and the lines of communication leading out of it could not meet all his needs.

The Allied response to this conundrum was a vast undertaking so unique as to be classed by many scoffers as completely fantastic: the construction of artificial harbors on the coast of Normandy.

The first time Eisenhower heard of this idea was when it was advanced by British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten in the spring of 1942. At a conference attended by a number of service chiefs, he stated that if ports were not available, the Allies would simply have to construct them in pieces and tow them in. This was met by both hoots and jeers, but two years later, that is exactly what happened.

General Eisenhower noted that two general types of protected anchorages were designed. The first, a “gooseberry,” was to consist only of a line of sunken ships placed stem to stern in such numbers as to provide a sheltered coastline in their lee upon which small ships and landing craft could continue to unload in any except the most violent weather.

The other type, a “mulberry,” was in reality a complete and practical harbor. Two of these were designed and built in Great Britain to be towed in pieces to the coast of Normandy. The major construction unit in the mulberry was an enormous concrete ship, termed a “phoenix,” boxlike in shape and so heavily built that when numbers of them were sunk end to end along a strip of coastline, they would most likely give solid protection against almost any wave action.

In addition, truly elaborate auxiliary equipment for unloading and all types of gear required in the operation of a modern port were also provided. The British and Americans were each to have one of the mulberry ports, while five gooseberries were also to be installed.

The Allies’ prior experience fighting in the Mediterranean theater had demonstrated that each of their reinforced divisions in active operation consumed about 600-700 tons of supplies daily, so they would need to make maintenance arrangements for the arrival of these quantities. Also, Ike’s staff in London would have to simultaneously build up reserves of troops, ammunition, and supplies on the beaches. This would permit the Allies to begin deep offensives within a reasonable time with the assurance that these could be sustained through an extended period of decisive action.

The offensive plan called for putting General Bernard Montgomery and his British Army safely ashore before the Norman city of Caen, while U.S. Army General Omar Bradley and the Americans disembarked at Omaha and Utah Beaches at the base of the Cherbourg Peninsula. Monty, whose army would then be the Allied force closest to Paris, would trick his old foe German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel into believing that the British were striving to break through the German defensive line and head for the not-so-distant French capital. In actual fact, Allied planners intended to use Monty as a decoy in order to divert the Germans to his front, leaving General Bradley as unengaged as possible while the Americans drove for the first real goal, Cherbourg at the northern end of the Cotentin Peninsula, which they hoped to take by D+17.

Once Cherbourg fell, General Bradley was to drive south down the Cotentin Peninsula on D+22, punching a hole through the German lines near Avranches. He could then fend off Rommel while General George S. Patton and the U.S. Third Army rushed south through this gap and slashed toward Rommel’s rear.

While the Anglo-American invasion forces penetrated inland, all the fighting equipment and supplies needed to seize their initial objectives would begin coming ashore, using the artificial mulberry harbors towed to Normandy by the Royal Navy from Selsey Bill in the United Kingdom. Heavy engineering materials needed to reestablish and refit captured ports; rebuild airfields; and repair railroads, bridges, and roads in rear areas would follow as the first phase of the invasion was successfully drawing to a close. One additional, but vitally important, part of the overall logistical plan allowed for the speedy removal of the expected wounded from the beaches and their prompt transfer to military hospitals in England.

On D+42, the Allies planned to tow from England the equipment for a harbor independent of the mulberries in the English Channel between Quiberon Bay on the Atlantic Ocean and the mulberry on the Normandy beaches, which would allow Ike to supply the various invasion armies for the long haul. This would continue until the ports of Cherbourg, Brest, L’Orient, and St. Nazaire were duly rebuilt, even though the Germans had badly sabotaged them before surrendering. It was hoped that after six weeks, these four French ports would be able to carry the load from there on. Until then, however, the mulberry would have to carry the load alone. If it couldn’t, the invasion would simply fail.

At best, Operation Mulberry was expected to serve as a temporary entry port for supplies and men needed to keep the invasion moving forward. When the quartet of real French ports was back in service, resupply and reinforcement efforts would shift away from the mulberry harbors and Quiberon Bay. The Allied drive across France to the Siegfried Line could then begin, with all supply problems solved. Operation Mulberry, then, was just the first important rung of a ladder into France, with Quiberon Bay being the second, and the four French ports the third.

At Selsey Bill, Ike saw in person the mulberries, and their immense size astonished him. Nevertheless, he was confident they would work. Eisenhower began to fit the pieces he saw into the picture they were to make when floated to the far shore, two vast artificial harbors to unfold under enemy fire on Normandy’s bare sands.

The tremendous English Channel tides were the very first obstacle to overcome. From high tide to low, the sea speedily dropped over 21 feet, a massive change in sea level. At low tide on the flat Norman beaches, the waterline pushed seaward a quarter of a mile twice daily. This moved the shoreline far out from the beach, with only wide stretches of bare sand where a ship might have floated just a few hours earlier.

Then there were the tidal currents that moved vast, surging quantities of seawater in and out the Channel every six hours, akin to so many rapid rivers running alternately west and east on the coast as the tides ebbed and flowed. These were all truly baffling currents of amazing strength, each enough to drive seamen frantic in handling vessels either onto or off the beach.

The shoreline itself—unprotected by any natural promontories or outlying islands—was fully exposed to the full sweep of the seas heading inward from the Channel. Vessels of all sizes in anything but fine weather would discover that unloading cargo on its unprotected, surf-pounded beaches was a nearly unsolvable problem.

Those were the main obstacles making the beaches untenable for any long-term cargo handling, even of light materials, not to mention heavy guns and tanks. The only answer was a protected seaport, either natural or contrived, such as the artificial harbors that Operation Mulberry provided.

Most important was the need for shelter from the open seas and their continuous surf. A massive breakwater was thus also needed, and on open coasts, this typically took years to build up from the sea floor. The Allies, however, built two such massive breakwaters, designed to be installed on the French sea floor for use in a matter of days.

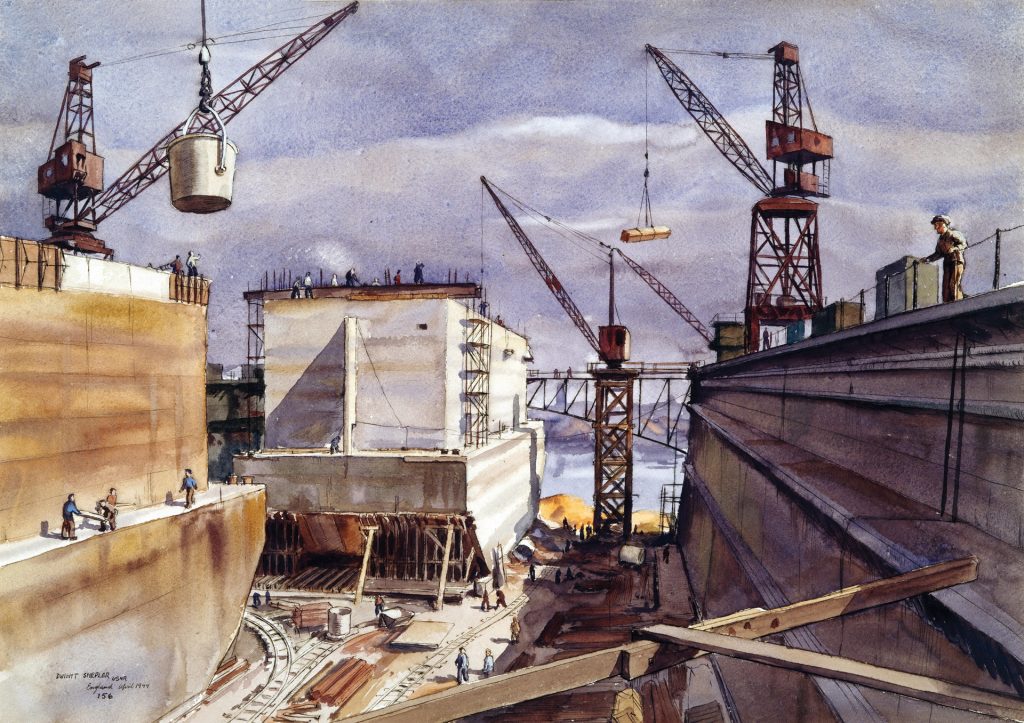

The 100 artificial breakwaters that Allied engineers built were nicknamed “phoenixes.” Each of the majestic, reinforced-concrete blocks was as heavy as a Liberty ship—displacing 6,000 tons—stood 60 feet high, ran 200 feet in length, and was 60 feet wide (tall as a six-storied building and a city block long). Despite its massive size, though, the segmentation of each phoenix into hollow, watertight compartments made it a buoyant, seagoing vessel. When the time came, they were floated up off the bottom of the sea on the English side of the Channel, towed a hundred miles across to Normandy, then sunk on the sea floor one mile off the beachhead. These would provide an enclosed, sheltered harbor for the invasion site.

Sunk end to end in two long strings off the French coast, they were to form two distinct breakwaters of two miles long, one for the American front, and the other for the British. This was 20,000 feet of breakwater combined, to be sunk a mile offshore in water 30 feet deep at low tide. Even at high tide, 10 feet of their top structure would be above the water’s surface to break the waves, thus protecting the artificial harbor inside from the rough Channel waters. They’d also provide calm water in their interiors for unloading cargo, either onto pier heads, or from small craft beached on the guarded sands. Operations could thus continue round-the-clock, undisturbed by surf or waves.

To maintain the necessary depth for ships inside, even at low tide, breakwater lines had to be lodged nearly a mile offshore to provide draft enough inside for berthing space along each inner phoenix wall. The estimated capacity at any given time was seven Liberty ships being unloaded. Countless smaller vessels would also take shelter within the mulberry harbors.

Something was also needed to break up meddlesome currents, so a short cross breakwater of more phoenixes was placed at the western end of each harbor, stretching from the inshore sands outward, and then perpendicular to the main breakwater, joined at its seaward end. This cross breakwater acted as a cork at one end of the harbor, throttling the dangerous shoreline rivers.

Then there was the pier head problem. To match the terrific supply tonnage to the limited number of vessels, there had to be a fast vessel turnaround on the far shore, meaning all unloading of tanks and heavy guns had to proceed off the bow ramps of the tank landing ships (LSTs).

Given the severe tide-level changes on the Normandy coast, normal pier heads built at the correct level to unload LSTs at high tide would at low tide tower so high above an LST’s bows that ramps could not possibly reach up to the pier head. If they did, could any vehicle possibly mount so steep an incline? The answer was to provide an artificial pier head.

Operation Mulberry provided an answer: the Lobnitz pier head. This vertically moving pier head maintained a fixed level above the changing surface of the sea regardless of the tide to facilitate the unloading of LSTs. Lobnitz pier heads, which Allied engineers interspersed among the sunken phoenixes, had a factory-like appearance, with four square towers at each corner that looked like chimneys and tremendous steel legs that pierced through the pier head’s hull, running down beneath the surface of the sea to anchor the structure to the ocean floor.

The movable pier head itself was controlled by intricate machinery inside its rectangular steel hull, rising and falling with the changing tides, maintaining its deck at a permanent height above the seas, but never immersed deeply enough to gain buoyancy for floating free. In addition, it always maintained enough weight to anchor the Lobnitz solidly.

Another important piece of the artificial harbor puzzle consisted of massive steel truss sections—“whales” in Normandy beachhead parlance—that floated on pontoons. Joined together into 3,000-foot lengths, they formed bridges on the surface of the water that ran seaward from a point just above the high water mark on the beach to connect with the Lobnitz pier heads well inside the protective breakwater area a half a mile out to sea.

Even when the water reached its lowest ebb at low tide, there still remained at each floating pier a high-enough water level to berth two LSTs. The vast tonnage, then, of tanks, self propelled guns, ammunition, supplies, and vehicles never ceased rolling ashore over those floating highway bridges from the Lobnitz pier heads—a vast stream of heavy, ocean-borne cargo that only the piers, cranes, and dock facilities of a major seaport would normally be able to handle.

For their part, the German General Staff fervently believed that no invasion could possibly be staged successfully at Normandy. They were patently wrong, as events later showed.

The U.S. Navy calculated that 100 sunken phoenixes at 6,000 tons displacement each would mean 600,000 tons of them nestled on the muddy ocean floor of Selsey Bill in the United Kingdom. When the time came for towing to enemy shores, would they actually work? Normally, such a thing would take two years to accomplish, while the Allies had but a few days to move them all.

In eight months, 20,000 British laborers built two million tons of steel and concrete into 600-odd sections towed by more than 100 tugs and assembled into two enormous floating ports. How successful were the mulberries in Normandy?

On D+10, an LST dropped its ramp onto the first completed pier runway of Mulberry A, and in two days, 24,412 tons of supplies and ammunition rolled ashore from the two mulberries. Then came the English Channel storm that Ike had feared all along. On D+13, gale- force winds with heavy surf pounded the Normandy coast, pushing landing craft against piers and tearing sections of them from their moorings, crashing them against each other. By D+16, Mulberry A was a mass of twisted wreckage, while Mulberry B was also damaged, though not fatally. Still, Allied supplies continued coming ashore.

When unloading began again on D+17, the British mulberry, using salvageable parts from Mulberry A, was back in operation, with the Americans landing16,400 tons on the open beaches.

On August 1, 1944, the Allied armies had enough strength ashore to finally break out from their Normandy beachhead and proceeded to liberate France and the rest of Nazi-occupied Western Europe—almost two months to the day after their initial landing. Thus, the mulberries, the Allies’ secret weapons in Normandy, have been judged by historians as a great logistical success.