By William E. Welsh

As Confederate General Robert E. Lee and his I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, rode together on horseback along the dust-choked Quaker Road from Glendale to Malvern Hill on the morning of July 1, 1862, they stopped to confer with Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill, whose division was moving up to the front line in preparation for an assault on the enemy position.

As the gray ranks marched past them, Harvey Hill leaned forward to share a piece of information about the terrain where they were to engage once again Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. A member of Hill’s staff, the Reverend L.W. Allen, who had been raised in the area, was familiar with the ground where the Yankees planned to make a stand. Allen had told his commander that Malvern Hill was well suited for defense, and McClellan’s military engineers would know how to fortify the position.

“If General McClellan is there in strength, we had better let him alone,” Hill said.

The soft-spoken Lee made a mental note of the information, but Longstreet dismissed it, saying, “Don’t get scared now that we have got him whipped.”

Over the past week, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had fought a series of battles that had driven McClellan away from the outskirts of Richmond and forced him to fall back to within a day’s march of his new supply base at Harrison’s Landing on the James River. Longstreet, whose troops had been bloodied in those battles, was optimistic that one more fight was more than the Federals could take. Hill had a more cautious attitude.

Hill didn’t appreciate the South Carolinian’s dismissive attitude, but he and Longstreet were on good terms, and so he decided not to argue the matter. Lee and his staff had only one map of the area, and it was a poor one, so the information was important, even if Longstreet chose to ignore it. Hill hoped that Lee would not ignore it.

The Peninsula Campaign Begins

Following the defeat of the Federal army at the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln replaced Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell with Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who had achieved minor victories over Confederate forces in the mountainous terrain of western Virginia. Early the following year, McClellan completed his plans to transport the Army of the Potomac by ship to the Union-held Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula between the York and James Rivers east of Richmond. Little Mac’s strategy was to outflank General Joseph Johnston’s Confederate forces along their Rappahannock River lines and fight one or more battles at the gates of Richmond that just might end the war.

The Federals set sail from Alexandria, Virginia, on March 17. On April 4, the Federal army began what would become a slow and tedious advance up the peninsula. After nearly six weeks, McClellan had advanced far enough toward Richmond to warrant shifting his supply base in mid-May to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, a tributary of the York. On May 31, the two sides clashed in a desperate battle at Seven Pines in which Johnston sought to hurl back the Federals to prevent them from besieging Richmond.

Although tactically a draw, the battle was a strategic victory for the Confederates in that McClellan took a defensive posture, ordering his forces to entrench. During the fighting, Johnston was struck in the right shoulder by a bullet and then immediately by a piece of shrapnel in the chest. With Johnston out of the fight indefinitely, Confederate President Jefferson Davis turned to Robert E. Lee to continue the offensive against Little Mac. Two days after Seven Pines, Davis appointed Lee commander of the Confederate forces defending Richmond. Lee named those forces the Army of Northern Virginia.

McClellan would soon come to doubt himself. He mistakenly believed that the Confederate forces greatly outnumbered his. It was a gross miscalculation, and one that would contribute to the unraveling of his entire strategy over the coming weeks.

Lee decided to wait until Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson concluded his campaign against Federal forces in the Shenandoah Valley before launching a major counterattack against McClellan. Jackson’s troops began their journey by rail to Richmond on June 23, and the following day Lee issued orders to his top generals, briefing them on his plans for an offensive against Little Mac.

Lee counterattacked on June 26 at Mechanicsville. In the days that followed, the Federals were driven back in a series of bloody battles, one of which occurred at Frayser’s Farm, also known as Glendale, on June 30. The Federals fought the Confederates to a standstill, but McClellan ordered his army to continue its retreat that night. Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, commanding the Union V Corps, was the first to arrive at the army’s next position atop Malvern Hill.

The Confederates awoke the morning of July 1 to find that the Federals had abandoned Glendale. During the past five days, the Confederates had forced McClellan to retreat as much as 20 miles. It was a significant achievement, but Lee wouldn’t be satisfied until he had delivered a fatal blow to the Army of the Potomac.

To Destroy McClellan’s Army

The morning after the Battle of Frayser’s Farm, Lee huddled with his lieutenants over a crude map showing the primary roads on the Virginia Peninsula. It was a shortcoming of the Confederate high command that Lee didn’t have a more precise map showing more of the secondary roads on the peninsula.

Lee traced his finger along Quaker Road, also known as Willis Church Road, and told those present—Maj. Gen. Ambrose Powell Hill, Maj. Gen. John Magruder, Harvey Hill, Jackson, and Longstreet—that they were to march down Quaker Road and get into position to attack the Yankees one more time. Lee’s map did not show Carter’s Mill Road, which paralleled Quaker Road to the west. His staff officers discovered the road later in the morning and used it to speed the arrival of part of the army to its proper positions.

After the meeting, Lee sent members of his staff to convey his orders to those not present, including Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, who was on the River Road to the southwest and Brig. Gen. Benjamin Huger, who was on the Charles City Road to the west and, it turned out, unaware that morning that the Federals had abandoned Glendale.

Lee believed that the Federals were weary from marching long distances and fighting rearguard actions over the past five days. He hoped that the fight that was brewing that day would be different from the others and that this time he would win a decisive battle that would result in the destruction of McClellan’s army.

Because Longstreet’s and A.P. Hill’s soldiers were exhausted from the previous day’s battle in which they bore the brunt of the fighting, Lee directed that they were to serve as the reserve. The main attack was to be made by Jackson and Magruder, whose commands were to be reinforced with additional troops. Huger’s division would join Magruder’s command, while D.H. Hill would join Jackson’s command. Further orders would be issued once Lee was able to make a personal reconnaissance of the field.

The Union Army’s Position on Malvern Hill

McClellan had not been present on the field to direct his forces at Glendale. Nor would he be present when the fighting eventually got under way at Malvern Hill. On June 30, he had ridden to Haxall’s Landing on the James River, which was closer to the fighting than Harrison’s Landing. At Haxall’s Landing, he boarded the gunboat Galena and sailed to observe a mission to bombard some of Holmes’s Rebels on the River Road.

It was clear by that time to McClellan’s staff that the general had completely lost his nerve during the past week and no longer had the stomach to command his army. Fortunately for McClellan, his corps commanders were well trained and experienced, and they cooperated with each other on the battlefield.

McClellan spent the night of July 30 aboard the Galena but rode to Malvern Hill the following morning to inspect Porter’s deployment of the army for the battle that was sure to occur that day. His greatest concern was that Lee would get behind his army and outflank him. The distance between his army and Haxall’s Landing, because of the James River’s course, was the greatest to the east. On that side, the Federals would have to cover a two-mile stretch of low-lying ground. McClellan advised Porter to place three corps facing east and use the other two corps to cover the north and west. The deployment made sense considering that the forward slope of Malvern Hill was narrow and only so many troops could be packed into that space. After his inspection, McClellan rode back to the Galena.

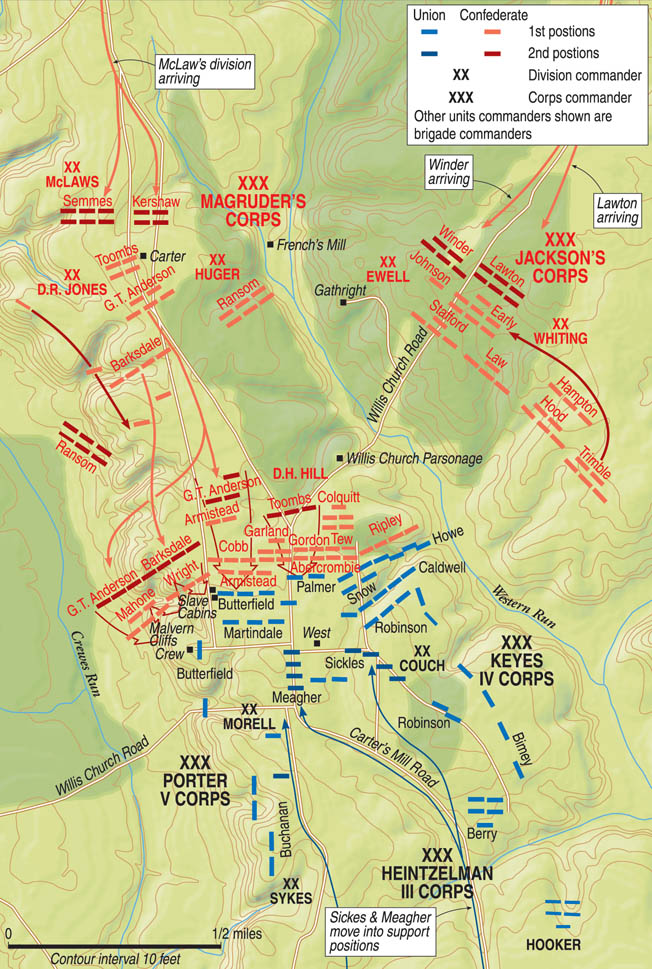

Porter had about 85,000 troops under his command. To secure Malvern Hill, he borrowed Brig. Gen. Darius Couch’s First Division of Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes’s IV Corps. Brig. Gen. George Morrell’s First Division of Porter’s V Corps was positioned on the west side of Malvern Hill, while Couch’s division was deployed on the east side of the hill. Facing west and covering the River Road was Brig. Gen. George Sykes’s Second Division of the V Corps, which was supported by 37 guns packed tightly together to prevent a Confederate advance along the River Road. Brig. Gen. George McCall’s Third Division of the V Corps was stationed on the rear of the hill as a reserve. The reserve was further strengthened by four brigades detached from Brig. Gen. Edwin Sumner’s II Corps and Brig. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman’s III Corps, as well as a battery of heavy artillery that belonged to McClellan’s siege train.

Facing east and deployed between Western Run and Turkey Island Creek from north to south were the rest of the corps of Heintzelman and Sumner, and also Brig. Gen. William Franklin’s VI Corps. Brig. Gen. John Peck’s Second Division of Keyes’s IV Corps was situated between Turkey Island Creek and the James River.

Porter was assisted in his deployments by Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, the chief topographical engineer of the army and a member of McClellan’s staff. The initial Confederate attack was expected from the north and perhaps also from the west. Facing north, the Federals were arrayed three brigades deep on each side of Malvern Hill. Together, Morrell and Couch had 17,800 men.

A Formidable Defensive Position

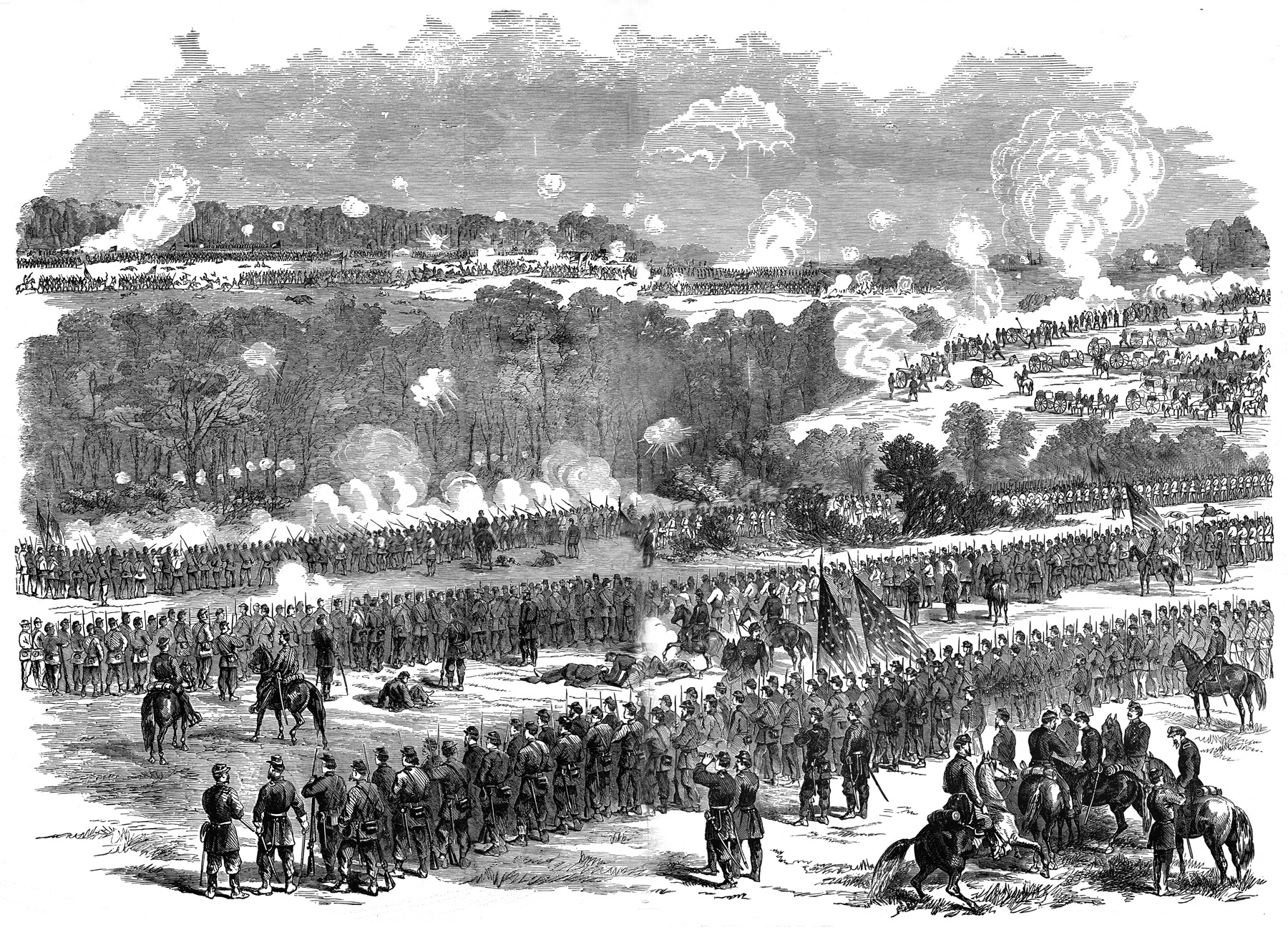

The two Federal infantry divisions facing north on Malvern Hill were supported by six batteries totaling 36 guns, with an equal number of guns on each side of the Quaker Road as it bisected the hill between the Crew and West houses. It was a formidable position, as Harvey Hill had told Lee.

“There was a splendid field of battle on a high plateau where the greater part of our troops and artillery were placed,” Humphreys wrote. If confidence came from numbers, the morale of those assembled must have been high that morning. The array of Federal power was a “magnificent sight,” said Humphreys.

Malvern Hill was not a rounded knoll but an elevated plateau that rose about 150 feet above river level. The strength of the position for the Federals was that the cultivated fields of the two farms on its forward slope furnished a splendid field of fire. The plateau was about three-quarters of a mile wide, and a mile and a half long.

Flowing in a meandering fashion southeast past the north slope of Malvern Hill was Western Run, a tributary to Turkey Island Creek, which emptied into the James River. The stream banks throughout the area were all heavily wooded, and crossing the streams was difficult for large units except at bridges or fords. While the east slope of Malvern Hill gradually dipped down to the creek, a portion of the west slope was a rock cliff that precluded any assault by infantry.

Opposite Malvern Hill was an unnamed plateau about the same height as Malvern Hill. The Carter and Poindexter farms north of Malvern Hill would serve as staging areas for the Confederate attack. Behind Western Run on its east bank was the Poindexter farm where Jackson’s command would deploy. Any Confederate troops marching along the Quaker Road and directed to deploy on the Carter farm situated on the Confederate right would have to cross Western Run. However, those that arrived on the Confederate right via Carter’s Mill Road would avoid having to cross Western Run.

“We Were on a Hot Trail”

On the Carter farm, Magruder’s command was to form up for an attack. Between the two plateaus was a dip in the landscape about 500 yards long that the Confederates would have to cross to reach the base of Malvern Hill. The Federal artillery atop Malvern Hill had sufficient range to not only target any infantry moving across the base of the hill but also to reach the farms beyond, where the Confederates would deploy for battle.

In his morning briefing, Lee instructed Jackson to take the road first and Magruder and Huger to follow him. Longstreet and A.P. Hill were to follow at the rear of the column. Any reconnaissance by the higher command would be handled as the troops were being deployed and not earlier. The reason for this was that “we were on a hot trail,” wrote Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox.

No sooner had the march begun than problems occurred. The inability of some of Lee’s commanders, particularly Magruder and Huger, to promptly get their troops marching on the correct road would disrupt Lee’s plans for a timely pursuit of the Federals that day. Magruder, who had not looked closely at Lee’s map during the briefing, decided to depend on local guides to lead his division to its position. More than one road in the region was named Quaker Road, and the guides led Magruder’s column west on the Long Bridge Road toward a small side road that also bore that name.

Lee was feeling sick that morning, and he had asked Longstreet to help him lead the army that day and substitute for him if necessary. Longstreet saw Magruder’s division marching east rather than south and sent a member of his staff after Magruder to inform him of his mistake. When Magruder did not turn around, Longstreet rode after him.

By the time Longstreet reached Magruder’s column, it had arrived at the intersection of the Long Bridge Road and the wrong Quaker Road. Longstreet was unable to convince Magruder of his mistake, but when one of Lee’s staff officers arrived with orders for Magruder to countermarch, Magruder obliged. Lee’s staff officer informed Magruder that he did not need to march all the way back to Glendale but instead could take Carter’s Mill Road to his pre-attack position. The mix-up delayed the arrival of Magruder’s command at the battlefront by three hours.

The Confederate Army Positions Around Malvern Hill

Huger also had trouble getting his men into position that morning. Because he was unaware on July 1 that the Battle of Frayser’s Farm was over, he had ordered two of his brigades—those of Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead and Brig. Gen. Ambrose Wright—to march south and attack the Federals at Glendale in the flank. When Armistead learned that there was no enemy to attack that morning at Glendale, he asked Lee for fresh orders.

At the conclusion of Lee’s conference with his lieutenants, a member of Lee’s staff rode to Huger’s headquarters on the Charles City Road to the north to inform him of the army commander’s plans for the day. Huger, a West Point graduate who was two years older than Lee, had extensive experience in ordnance matters, but his talent for leading infantry left much to be desired. His experience in the old army perhaps contributed to his reluctance to allow anyone other than himself to give orders to his troops. That arrogance would contribute to the problems Lee faced getting his troops into position for the attack on Malvern Hill.

Since Magruder was not going to be able to deploy as quickly as Lee had hoped, Lee ordered Armistead and Wright to move by the Quaker Road and deploy on the right of the Confederate line of battle where they would lead off the attack on the Confederate right. The two brigadiers led their combined 2,500 men to the location specified and took up a position behind a ridge to await the arrival of artillery to contest the Federal guns.

Meanwhile, Jackson’s command, which comprised four divisions, began arriving on the Poindexter farm about 11 am. For the coming battle, Jackson’s command had been supplemented with two new divisions. One of the attached divisions was led by Harvey Hill, and the other was led by Brig. Gen. William H.C. Whiting.

Whiting’s men marched at the head of Jackson’s column and were the first to arrive at the Poindexter farm, where they took up a position on the extreme left of the army. Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell’s division took up a position straddling the Quaker Road behind Western Run. When Harvey Hill’s division arrived in the early afternoon, it halted in the woods behind the Willis Church parsonage behind Western Run. Harvey Hill’s division was positioned in the center of the Confederate line, a place that Lee originally had hoped that Huger would deploy. Jackson’s other division, led by Brig. Gen. Charles Winder, brought up the rear. Not including Harvey Hill’s division in the center, Jackson had 20,000 troops in three divisions on the Confederate left flank to hurl at Porter.

Bombardment From the Federals’ Guns

By 12:30 pm, Armistead and Wright had their troops in position and were conducting their own reconnaissance of the Federal position on Malvern Hill. They saw a white house with several barns around it at the top of the hill and some other buildings on the forward slope toward them, which were the slave cabins. This was the Crew farm. As for the Federal artillery, the guns were nearly hub to hub. Behind them were several lines of infantry. The guns had a clean sweep of the open ground across which the Rebels would have to charge to reach them. Harvey Hill, who was making the same observation farther east, saw the same menacing forces.

“If the first line was carried,” wrote Harvey Hill, “another and another still more difficult remained in the rear.”

The Federal line “seemed almost impregnable,” said Major Joseph Brent, one of Magruder’s staff officers, who rode ahead of Magruder’s column to observe the Federal position.

At 1 pm, the Federal guns facing north toward the Confederate main line began a random but steady bombardment of Confederate forces opposite them. As the shells crashed around them, graybacks in the open hugged the ground, while those in the woods sought protection behind trees. “The fire was a terrible one, and the men withstood it well,” wrote Armistead.

Poor Orders From Lee

Lee had chosen to make his headquarters at a blacksmith shop opposite the Willis Church parsonage. That morning, Lee had told Longstreet to make a personal reconnaissance of the enemy position from the right side of the Confederate line of battle, while he undertook a reconnaissance of the left side. They met back at the blacksmith shop at noon to discuss final plans for the attack. Both had seen the need to establish strong artillery positions to counter the Federal artillery arrayed against them and knock out as many Federal guns as possible before the infantry assault began.

Lee gave verbal orders to his chief of staff, Colonel Robert Chilton, which were to be crafted into a general order and distributed to the division commanders and also to Armistead. Lee’s plan was to establish a “grand battery” on each flank that together would provide a converging fire on the Federal guns. If the bombardment was successful, then the infantry should advance. If not, an alternate plan of attack might be developed, Lee said.

The order, as penned by Chilton, read as follows. “Batteries have been established to act upon the enemy’s line. If it is broken as is probable, Armistead, who can witness the effect of the fire, has been ordered to charge with a yell. Do the same.”

The order as written left much to be desired. It not only made the presumption that the Confederate counterbattery fire was likely to succeed, but also left the authority for deciding whether the attack should go forward in the hands of a brigadier general. Moreover, the decision to make the signal for the attack a yell was absurd, as it would be nearly impossible for other commanders to know whether the yells they were hearing were from Armistead’s brigade. To make matters worse, Chilton failed to put a time on the order to indicate when it had been issued.

Organizing the Confederate Batteries

Jackson’s command had 10 batteries, and some of those had lumbered along the Quaker Road with the divisions of Whiting and Ewell, which had arrived at the front by early afternoon. Unfortunately for Jackson and the army as a whole, his chief of artillery, Colonel Stapleton Crutchfield, was ill that day and no replacement had been designated for him. Therefore, no officer was on duty to call up the batteries and show them where to deploy.

Harvey Hill, whose troops were likely to go forward into battle as they were positioned on Armistead’s left flank, had no artillery at all. Hill had sent his artillery many miles to the rear for an overhaul under an order previously given to him. It seemed only logical that he should be given replacement batteries from the army’s reserve, but no one could locate Brig. Gen. William Pendleton, who commanded the reserve artillery. Without Pendleton’s permission, it would be impossible to obtain any of the 14 batteries in the reserve.

The responsibility for obtaining guns for service in the left grand battery eventually fell to Jackson. Stonewall rode from the Poindexter farm out to the Quaker Road in search of his division’s batteries. He was able to locate three batteries—Staunton Artillery, Rockbridge Artillery, and Rowan Battery—and ordered them to drive their guns onto the Poindexter farm.

As for the right grand battery, it would have the advantage of more individual batteries, but that factor was negated by the matter of each going into action at different times. The batteries that unlimbered on the ridge in front of Armistead came from four different commands. Two batteries each came from Magruder’s and Huger’s divisions, one from A.P. Hill’s division, and one from the artillery reserve. Seeing the need for as much artillery support as possible, Powell Hill, who was on the north end of the Carter farm near the Long Bridge Road, sent forward his best battery, Captain William Pegram’s Purcell Battery. On his own initiative, Captain Greenlee Davidson, commanding the Letcher Battery which belonged to the reserve artillery, put his battery into action in support of Magruder.

The availability of batteries on the Confederate right was never in question. In addition to the six that either went into action or that attempted to go into action but were driven off by the Federal guns, there were another six batteries nearby that stayed idle. Ultimately, the responsibility for the failure of these batteries would rest with Magruder, who had as many as 16 batteries under his direct control that day, and six more were attached to Huger’s division, giving Magruder a total of 22 batteries, each with four to six guns. While it would have been impossible to fit all of those on the ridge opposite the Crew house, it certainly could have accommodated more than one battery at a time.

Of the “Most Farcical Nature”

The Confederate batteries began answering the Federal guns at about 2 pm. The guns of the left grand battery opened up first. The leadership crisis on the Confederate right delayed the deployment of the guns of the right grand battery. When the Federal artillery officers saw the Confederate guns unlimber on the Poindexter farm, they immediately switched their harassing fire to the Rebel artillery crews.

It was testimony to their skill and battlefield experience that the Southern artillery crews on the left flank could stand up under such fire. Their initial performance was impressive. They quickly found the range of the enemy targets and put out hot counterbattery fire. The shells from the Rebel guns produced considerable casualties among the Federal artillery crews and compelled some Yankee officers to pull back their exposed infantry. The duel between the left grand battery and the Federal guns atop Malvern Hill reached its peak about 2:30 pm.

Since they lacked any support from the right grand battery, the guns on the Confederate left initially took the full brunt of the Federal batteries atop Malvern Hill. Solid shot from Yankee smoothbore and rifled artillery sailed over Western Run and landed directly on the three Rebel batteries that had moved into position. The Federal artillery fire smashed gun carriages, and it killed and wounded horses and men. The Confederate left grand battery, despite the valor of the gunners, was of the “most farcical nature,” wrote Harvey Hill.

The Staunton Artillery was the last battery to retire on the Confederate left. Its commander, Captain William Balthis, who was struck by seven shell fragments during the artillery exchange, urged his men to stand up to the storm of Federal shells as long as possible. When his battery ran out of ammunition, he gave the order to withdraw.

Beginning at about 2:30 pm, the first batteries on the Confederate right flank attempted to go into action. The Federal artillery crews, particularly those in front of the Crew house, turned their guns on the new threat. The Federal artillery fire against the right grand battery was so fierce that no battery could stay in action for long. Davidson, commanding the Letcher Battery, discovered that his battery could stay in action by having the crews load the guns behind the crest of the hill. Once loaded, the men ran the guns to the crest, fired them, and ran them back down the hill to reload. Eventually, Davidson also gave up the mismatched contest. After 3:30 pm, other batteries on the Confederate right tried periodically to go into action, but they were driven away almost immediately.

The performance of the Federal artillery atop Malvern Hill was flawless and would be remembered by the Confederates long after the battle was over. Federal gunboats participated in the bombardment in the early afternoon, but their rounds fell indiscriminately on both blue and gray soldiers. Porter was furious over this and sent orders via the signal corps for the ships to cease their fire.

Armistead’s Attack

The balance of Huger’s division, which consisted of Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s Virginia brigade and Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom’s North Carolina brigade, arrived on the Carter farm at about 3:30 pm. Huger chose not to lead them to the front, but instead remained at the junction of the Long Bridge Road and Carter’s Mill Road, sulking about how Lee had circumvented him by issuing orders directly to his troops. When Brent finally located him, Huger acted in a truculent manner. Brent told the South Carolinian that Magruder wished to align his units with Huger’s division when it arrived and asked Huger where his men were deployed. “[Some of my troops have been moved] without my knowledge by orders independent of me, and I have no further information enabling me to answer your inquiries,” said Huger.

While Huger bickered with Brent, Armistead and Wright had watched Yankee skirmishers from Griffin’s brigade of Morrell’s division walk slowly down the slope of Malvern Hill toward their position. Their purpose was to try to shoot some of the artillerymen manning the Confederate guns. To counter the threat, Armistead decided to launch a limited attack to drive away the skirmishers.

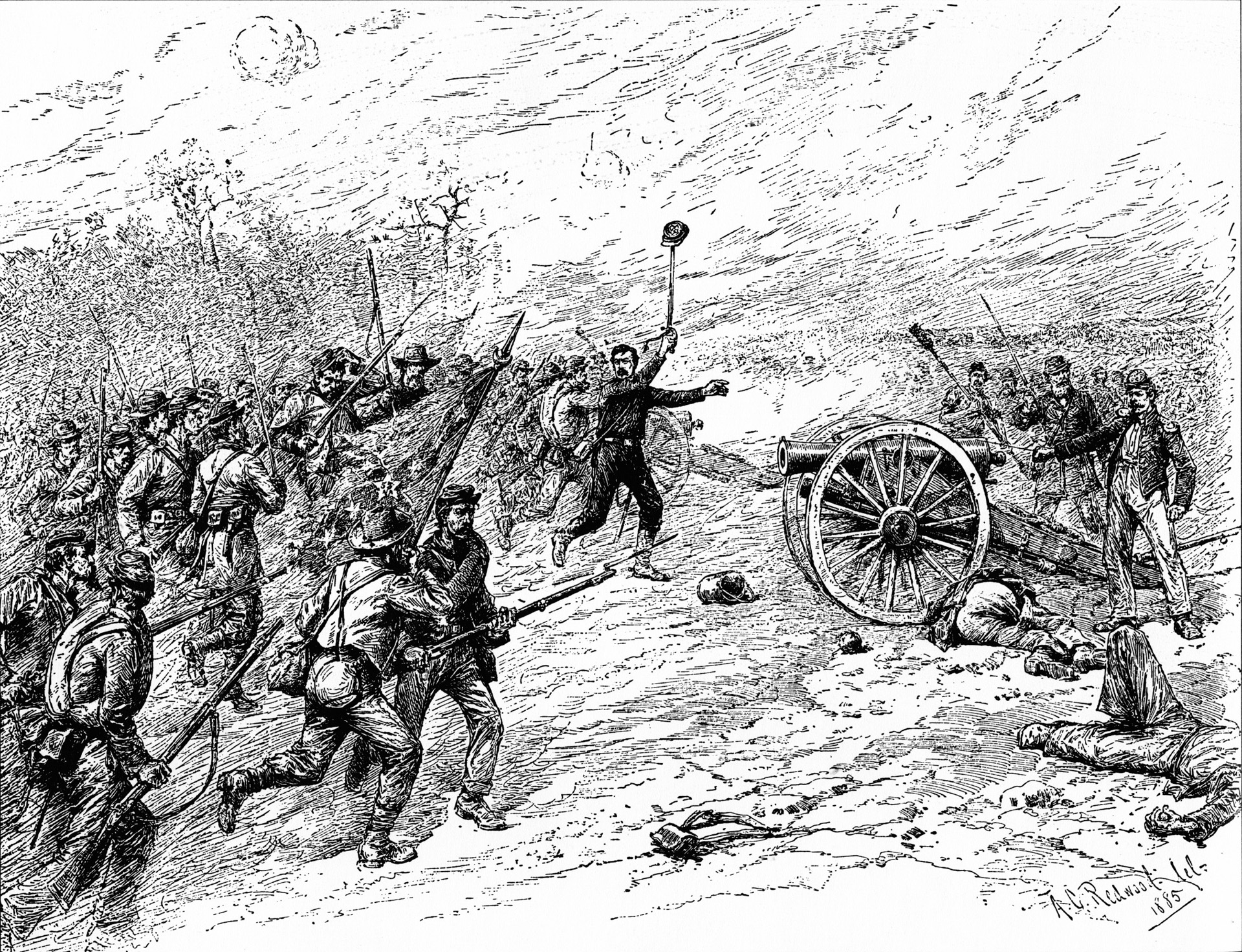

For the mission, Armistead called up his three best regiments, the 14th Virginia, 38th Virginia, and 53rd Virginia. The soldiers in his brigade had been waiting in the woods behind the ridge where the Rebel artillery had gone into action. When the three regiments were in position, Armistead put his hat atop his sword and waved it in a circle as a signal for them to advance. At about 3:30 pm, the gray infantry swept over the ridge with their weapons at the trail arms position. Once over the hill they charged the Federal skirmishers, who, realizing they were heavily outnumbered, quickly fell back toward their main line. During the charge, “We encountered a red hot storm of every missile,” wrote Colonel Harrison Tomlin of the 53rd Virginia.

Armistead’s men advanced about 500 yards, farther than Armistead had intended, before halting to take cover in a shallow depression at the base of Malvern Hill. Armistead had only deployed them to drive the skirmishers off, but the colonels leading the three regiments thought he meant for them to charge the main Federal position.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, they quickly became the primary target of the Federal artillery. Armistead, realizing that they would be chewed up badly if ordered to retreat, decided to leave them in position until the general assault began, at which point they could join it. The three regiments would subsequently remain in position for nearly two hours under heavy fire. “We held our position through all the storm of canister and shell,” wrote Colonel Edward Claxton Edmonds of the 38th Virginia.

Lee Scouts Out the Union Position

While the Virginians were hunkered down at the base of Malvern Hill, Lee was once again in the saddle. He rode with an escort beyond the Confederate left to reconnoiter the Federal position on the east side of Malvern Hill and determine whether it might be carried by a flank attack. If he felt it was feasible, he would order Longstreet and Powell Hill to strike the Federals in the flank either that evening or perhaps the following day. What he found was the bulk of the Federal army in a strong position. The ground was also marshy where Western Run joined Turkey Island Creek. Lee’s reconnaissance put an end to any thought of turning the Union right flank.

By 4 pm, the general mood among the high-ranking officers on the Confederate left, including Jackson, Harvey Hill, and Whiting, was that there would be no major attack on the Federal position that day because it was too strong.

All present had just borne witness to the skill of the Federal gunners, and it was probably clear to them that the Federals were eager for revenge following their series of humiliating retreats over the previous week.

“Prince John” Magruber

Magruder arrived at the front about 4 pm by way of the Carter’s Mill Road in advance of his troops and made his own assessment of the situation.

A tall and handsome West Point graduate who spoke with a slight lisp, Magruder had served in the Mexican War as an artillery officer and had performed so well that he was brevetted three times during that conflict. After the war, he had served as commandant of the artillery school at Fort Leavenworth, where he had shown a taste and flair for pomp and ceremony, thus earning the sobriquet “Prince John.”

Magruder’s first post in the Confederacy was as a colonel in command of the small group of Confederate forces deployed on the Virginia Peninsula. Setting up headquarters at Yorktown, his orders were to contain Federal forces advancing west from Union-held Fort Monroe at the tip of the peninsula. In April 1862, while defending the Warwick Line against McClellan’s forces in the opening act of the Peninsula Campaign, Magruder showed a knack for defensive warfare and for military theatrics by moving his small force in such a manner as to deceive the Federals that his force was much larger. For his achievements, he was appointed brigadier general in June and four months later promoted to major general.

During what would become known as the Seven Days Campaign, Lee slowly began to see shortcomings in the 53-year-old Magruder’s aptitude for offensive operations. Still, Magruder was one of his highest ranking generals, and Lee had enough residual faith in him after the action at Glendale to give him a major role in the fighting at Malvern Hill.

“General Lee Expects You to Advance Rapidly”

When Magruder saw how far Armistead’s men had advanced, he mistakenly interpreted it as a small success. When Lee returned from his reconnaissance of the Federal right flank, he received a dispatch from Magruder informing him that Huger’s troops had achieved a promising success that Magruder planned to exploit if possible.

Lee also received word from Whiting that some of the Federal troops on Malvern Hill were moving back, which Whiting misinterpreted as the beginning of a general withdrawal. Whiting’s erroneous observation was probably derived from his seeing some of the Federal infantry taking cover during the brief bombardment by the Confederate left grand battery.

Although Lee might have been contemplating calling off the attack due to the fact that the artillery had failed to achieve any noticeable success, he took these reports as good omens. Hoping that Magruder could expand on whatever success had been achieved by Armistead on the other end of the battlefield, Lee sent a dispatch to Magruder with the following order: “General Lee expects you to advance rapidly. He says it is reported the enemy is getting off. Press forward your whole command.”

Magruder was prepared to hurl six brigades at the Federal lines in his initial assault. His plan called for using the four brigades of Huger’s division and two brigades from Brig. Gen. David R. Jones’s division. But when Magruder sent orders to Huger’s other two brigadiers, Mahone and Ransom, Ransom refused to move unless Huger ordered him to do so. Since Huger was nowhere near the front, this proved impossible.

When Magruder rode back to the Carter farm to bring forward Jones’s division, he came upon his own division at the front of the column of troops. Magruder’s division comprised the brigades of Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb and Brig. Gen. William Barksdale. Prince John ordered them to prepare to assault the Federal position. He also gathered Mahone’s Virginia brigade. Unlike Ransom, Mahone was more than willing to put this troops in the fight with or without Huger’s permission.

“At Every Step My Brave Men Fell Around Me”

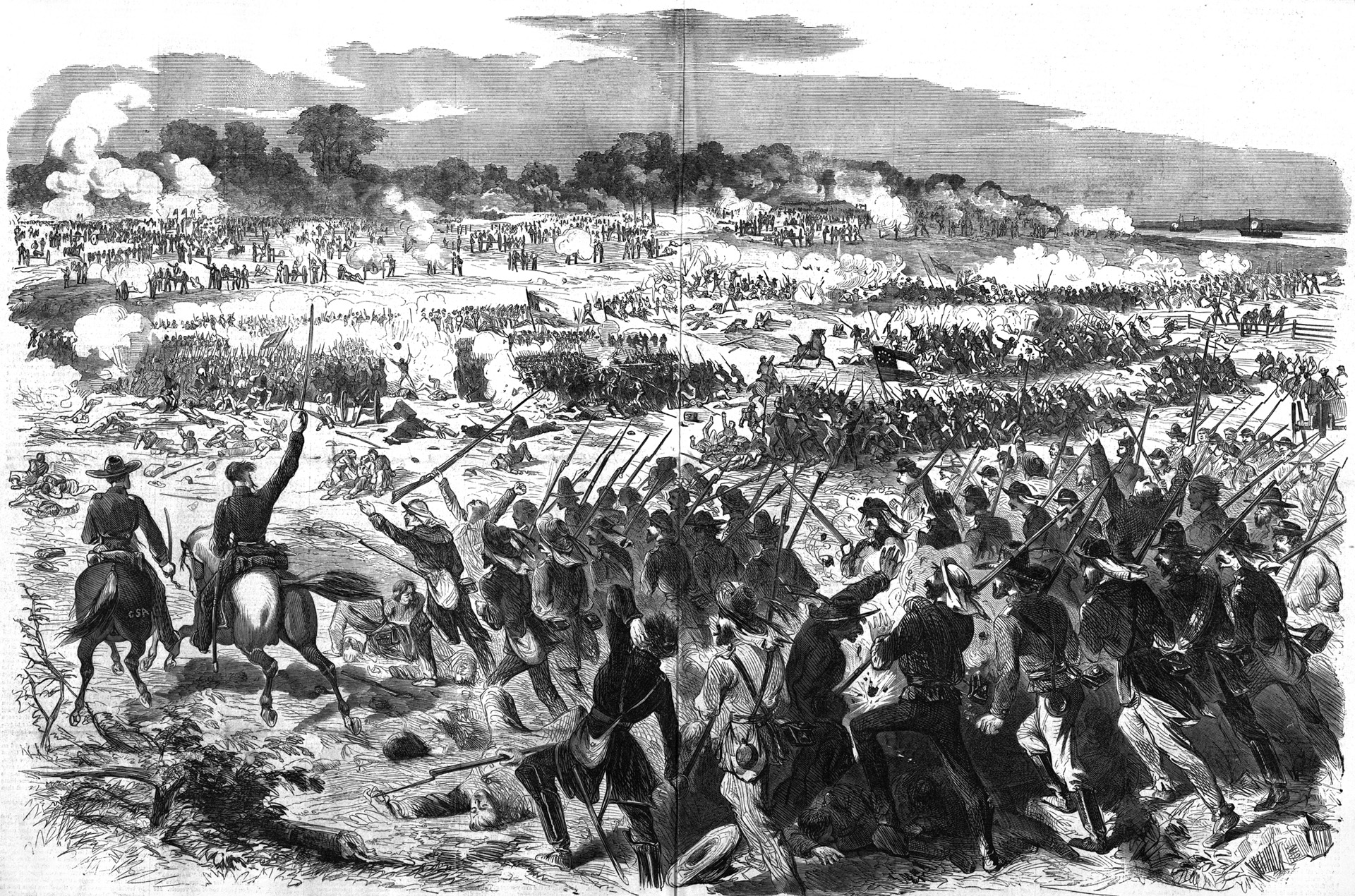

At 4:45 pm, Magruder sent one of his aides to Wright with orders to charge the Federal guns by advancing to the right of Armistead’s already committed troops. Shortly afterward, Magruder sent Mahone to follow Wright to add weight to his attack. Meanwhile, he sent Cobb forward on the same path as Armistead’s three regiments had taken. Barksdale’s Mississippians were farther back and went forward in a later wave. Magruder’s first wave had only half the number of men he had originally intended.

Some of the brigades Magruder ordered into battle that day became pinned down immediately by the Federal guns. Others pushed forward unsupported on either flank, which was the case with Wright’s brigade in the first wave. “At every step my brave men fell around me, but the survivors pressed on until we had reached a hollow about 300 yards from the enemy’s batteries on the right,” wrote Wright. Bluecoats from the 4th Michigan of Griffin’s brigade tried to get around Wright’s left flank and cut him off, but Wright saw the threat and ordered the 3rd Georgia on the brigade’s left flank to change front and engage the Federals. For nearly an hour, Wright’s brigade fought Federal infantry in the vicinity of the slave cabins on the Crew farm. During that time, it suffered heavy casualties from canister fired by a battery of Napoleon smoothbores led by Lieutenant Adelbert Ames of Battery A, 5th U.S. Artillery.

When Wright’s Regiment went forward, the Confederates of Armistead’s brigade, who had been pinned down by the Federal artillery, rose up and with a cheer resumed their advance up Malvern Hill. They made a valiant attempt to reach the Federal line to no avail. “Six times was the attempt made to charge the [Federal] batteries by the regiments of Armistead’s brigade, and as many times did they fail for want of support on the left,” Colonel Edward Claxton Edmonds of the 38th Virginia wrote in his report. The carnage among the 38th Virginia exemplified the severe casualties suffered by the men who charged into the teeth of the Federal guns. Before the day was over, eight color bearers of the 38th were either killed or wounded trying to carry the regiment’s colors forward.

900 Yards of Open Ground

The lack of support noted by Edmonds was soon to be corrected. By 2 pm, Harvey Hill had received Lee’s order penned by Chilton. When the Confederate artillery bombardment proved to be a resounding failure an hour later, Hill sent a note to Jackson, under whose command he had been placed, asking Stonewall whether his five brigades should participate in a subsequent charge against the daunting Federal position. Jackson’s response was that Hill was obligated to follow Lee’s orders since they had not been rescinded.

Nevertheless, it seemed madness to proceed. Hill and his subordinates were thinking about where they would camp for the night when several brigades to their right emerged from the woods and with a shout began advancing rapidly up the long slope of Malvern Hill. “Bring up your brigades as soon as possible and join it,” Hill said to his brigade commanders.

The first wave of Hill’s attack consisted of two brigades: Brig. Gen. Samuel Garland’s North Carolinians and Colonel John Gordon’s Alabamians. The two brigades emerged from the woods at 5:30 pm in one long line with Gordon on the left and Garland on the right.

Garland’s Tarheels had to cover about 900 yards of open ground over neatly mowed fields to reach the Federal batteries. About halfway to their objective, the artillery and musket fire was so severe that the Rebels halted, dropped to the ground, and began firing from the prone position, which was contrary to Garland’s orders. “I sent my acting aide-de-camp … to inform Maj. Gen. Hill that unless I was reinforced quickly I could effect nothing, and could not hold the position then occupied,” wrote Garland.

Reinforcing Couch

Couch’s division was deployed facing northeast a few hundred yards in advance of the West House, and its soldiers were able to fire into Gordon’s flank as he advanced toward the crest of the hill. Couch had deployed two of his brigades in one line with another behind it in reserve. To engage the left front rank of Couch’s division, which was held by Brig. Gen. Innis Palmer’s Third Brigade, Hill ordered Colonel C.C. Tew to attack Palmer. Tew had inherited command of Brig. Gen. George B. Anderson’s brigade when the Anderson was wounded in a skirmish leading his men across Western Run. Advancing on Tew’s left was Brig. Gen. Roswell Ripley’s brigade. Hill ordered his last brigade led by Colonel Alfred Colquitt to follow Gordon.

The advance of the 8,200 Confederates in Hill’s division worried Couch. He asked Porter for assistance, and the V Corps commander sent word to Sumner that he needed two of Sumner’s brigades immediately. Sumner, commanding the II Corps, sent Brig. Gen. John Caldwell’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Israel Richardson’s division at the double quick from the rear of Malvern Hill. Caldwell’s Federals went into the fight on the far right of Couch’s line. Heintzelman, who was conferring with Sumner when the request for support came, volunteered to send Dan Sickles’s brigade from his corps into the fight as well. Sickles’s five New York regiments formed up in a lane that ran behind the West House, where they could easily reinforce Couch’s position.

“We Murdered Them by the Hundreds”

Some of Gordon’s men came within 200 yards of the Federal guns, but Brig. Gen. John Abercrombie’s Second Brigade of Couch’s division, which had been in reserve, shifted east to block Gordon’s assault and support the artillery crews. On Hill’s left flank, the Georgians and North Carolinians of Ripley’s brigade reached the level ground at the crest of the hill, but they also received double canister from level gun barrels that prevented them from advancing further.

To Ripley’s right, Tew’s brigade also received heavy destructive fire from the menacing enemy cannon. “Our men charged gallantly at them,” wrote William Calder of the 2nd North Carolina of Tew’s brigade, noting, “The enemy mowed us down by the fifties.”

Time and time again, Hill’s men rose up from the prone position and attempted another charge, but each time they were repulsed. “We murdered them by the hundreds, but they again formed and came up to be slaughtered,” wrote Lieutenant George Hagar of the 10th Massachusetts of Palmer’s brigade.

Despite the approach of night, Magruder continued to gather troops to reinforce his attack. He rode back to the Carter farm, where he found Jones’s and McLaws’s divisions approaching the front. Together they had four brigades, all of which would go into the fight.

“I Guess You Had Better Not Try it.”

Prince John wasn’t the only one looking for more troops to lead up the hill. Harvey Hill, who watched as wounded streamed to the rear, also cast around for more troops to reinforce whatever success his division was having on the slopes of Malvern Hill. Finding the four Georgia regiments belonging to the brigade of Brig. Gen. Robert Toombs of Jones’s division without their commander, Hill led them forward to support his division, even though they belonged to Magruder’s command. Meanwhile, Magruder put Jones’s other brigade, led by Col. George T. Anderson, into action on the far right of the Confederate line in support of Mahone and Wright.

The piecemeal insertion of these Confederate brigades into the fight continued when McLaws’s division arrived at the front. One of Magruder’s aides broke up McLaws’s division, sending the brigade of Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolinians to support Hill and dispatching the brigade of Brig. Gen. Paul Semmes to support Magruder’s command.

As more Confederates joined the assault on Malvern Hill, Federal artillery reserve commander Colonel Henry Hunt ordered the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery to fire its 32-pounder siege guns at the sea of gray infantry trying to take Malvern Hill. The big guns cut 10-foot swaths through the charging ranks with a single shell. Hunt also saw to the steady replacement of field batteries on the front line as they ran out of ammunition and were withdrawn.

By 7:30 pm, Harvey Hill had broken off his attack against the Federal right atop Malvern Hill, leaving two brigades from Magruder’s command—those of Kershaw and Toombs—to carry on a desultory exchange of fire with the bluecoats of Couch’s division. Jackson had watched Harvey Hill’s division as it was mauled by the Federal artillery and infantry. Stonewall’s troops had waited to be ordered forward, but Stonewall had no intention of hurling them against Couch’s reinforced division.

When Jackson saw Trimble preparing to lead his brigade against the Federal right, he inquired as to Trimble’s intent. “What are you doing, General Trimble,” asked Jackson. “I am going to charge those batteries, sir,” replied Trimble. “I guess you had better not try it. General Hill has just tried it with his whole division and been repulsed. I guess you had better not try it, sir,” Jackson said.

The Last Confederate Assaults

The Confederate units near the crest of the hill made one last attempt to capture the Federal guns in front of them before darkness prevented further fighting. Wright’s brigade had clung precariously to its position near the slave cabins of the Crew farm for nearly two hours when it rose up from the hollow where it had sought protection from the hailstorm of canister and went over the crest of the rise toward the guns on Morrell’s left flank. Screaming the rebel yell they ran headlong into a line of Federal infantry that had been waiting below the guns for just such a charge. “Upon them we rushed with such impetuosity that the enemy broke in great disorder and fled,” wrote Wright. But the delay bought enough time for the Federal artillery to complete a withdrawal that was already under way to the Crew house to prevent the guns from being outflanked by other Confederate regiments advancing obliquely on Morrell’s left.

Similarly, Kershaw’s South Carolinians made a last assault astride the Quaker Road toward the Federal guns that were about 200 yards in front of the West house. They nearly overran Captain John Edwards’s Battery B, 3rd U.S. Artillery, but once again Yankee infantry held them up long enough for the guns to be withdrawn.

By 8:30 pm, some of the Confederates moving up the hill had begun accidentally firing into the backs of fellow Southern soldiers in front of them. The Federal gun crews continued to load and fire into the gloaming until it was apparent that the Confederates had finally broken off their attack. When the guns fell silent, a steady chorus of cheers rose from the top of the hill as Federal troops celebrated their triumph that day. For the Confederates, it must have been a deeply disheartening moment as they reflected on the disaster that had befallen them and listened to the pitiful cries of their wounded comrades.

Who Was Responsible For the Confederate Disaster at Malvern Hill?

There was no shortage of blame and recrimination among the Confederate high command in the aftermath of the battle. Lee asked Magruder why he had chosen to send the troops under his command to certain death for no gain, given the clear advantage the Federals had in artillery. Magruder’s reply was that Lee had twice ordered him to attack, and for that reason he had no other choice.

Ultimately, the responsibility for the debacle belonged to Lee. He had issued vague orders and relied on faulty intelligence from more than one source. Lee’s complaint, which was a recurring theme throughout the Seven Days Campaign, was that his subordinates failed to carry out his orders in a timely manner. Following the battle, Magruder, Holmes, and Huger were all transferred out of the Army of Northern Virginia.

Lee’s army at Malvern Hill suffered roughly 5,500 casualties, while McClellan’s suffered about 3,200 casualties. Once the battle was over, McClellan ordered his army to retreat again under cover of darkness. It pulled back to Harrison’s Landing, where it entrenched and was able to rely on a flotilla of gunboats for additional firepower.

Lee instructed cavalry commander General Jeb Stuart to probe the Federal defenses at Harrison’s Landing, and Stuart reported that he could find no weaknesses in McClellan’s position. Porter had managed to preserve the Army of the Potomac’s reputation at Malvern Hill. McClellan managed to keep his army at Harrison’s Landing for six weeks while he pleaded with Washington for more troops and mulled another advance on Richmond. On August 3, McClellan received orders to return his army by ship to Alexandria, Virginia. Despite his protests, McClellan’s army was to unite with Maj. Gen. John Pope’s newly constituted Army of Virginia. In less than a month, Pope would meet with disaster at the hands of Lee and his lieutenants.

what if the Union had counter-attacked?

Good question. In view of McClellan’s proclivity to avoid set piece battle, Malvern Hill excepted, his actions in retreating to Harrison’s Landing are not surprising and was simply one more incident contributing to Lincoln’s frustration with his lack of aggressive contact with the enemy. It would appear that a follow up attack by the Union army the next morning could have further damaged Lee’s army though I doubt it would have been a war ending event that McClellan was originally hoping for.